Abstract

Power-to-methane technology is a promising solution to facilitate the use of excess variable renewable energy for biomethane production. In this approach, hydrogen produced via electrolysis is used to upgrade raw biogas, which can be subsequently used as fuel or stored in the gas grid. Ex-situ biomethanation is an emerging technology that could potentially replace conventional energy-intensive biogas upgrading methods and allow CO2 utilization for biomethane production. This work provides a comprehensive overview on the current status of ex-situ biomethanation with particular attention to trickle bed reactor. The review includes description of ex-situ biomethanation and summarizes previous works on this topic. The key elements related to operational conditions, efficiency, and microbiology of ex-situ biomethanation using trickle bed reactor are described here. Additionally, the review highlights the technical and economic issues that have to be addressed for future development and large-scale implementation of ex-situ biomethanation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Biogas is a mixture of methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2) and small quantities of other gases produced during anaerobic digestion (AD) of organic matter in an oxygen-free environment (IEA 2020). Due to the presence of CH4 in biogas, it possesses energetical properties that can be converted into electricity/heat or can be used as platform chemical for e.g., protein manufacturing (Jones et al. 2020). The content of CH4 in biogas depends on the organic matter characteristic and can range from 55 to 80% (Barragán-Escandón et al. 2020). However, the CO2 in biogas occupies a significant part of its volume (from 20 up to 45%) representing no energetical use (calorific value = 0.0 MJ/m3). Due to that, the calorific value of biogas ranges between 20 and 30 MJ/m3. Upgrading biogas to biomethane increases the energetical value of biogas, that can be approximated to the calorific value of pure CH4 (37.7 MJ/m3) (Gasunie 1980). Therefore, it is of interest to increase the share of CH4 in the produced biogas.

Currently, most of the full-scale biogas upgrading plants are based on the physicochemical CO2 removal. Commercially, the chemical/water scrubbing, membrane separation, pressure swing adsorption (PSA) are widely utilized in Europe for CO2 removal in biogas plants (Petersson and Wellinger 2009). These upgrading methods are robust, reliable, and capable to treat high gas loadings. However, these methods are expensive and consume energy due to high pressures (e.g., PSA), chemicals addition (e.g., chemical scrubbing) or use of expensive equipment such as membranes.

The methods for CO2 reuse in biogas production recently gained much more interest. These methods treat the CO2 as a potential resource for CH4 production. The CH4 produced from CO2 can increase the share of CH4 leaving the AD that can be e.g., readily injected into the existing gas grid and is a good platform for novel low carbon products (Burkhardt et al. 2015; Savvas et al. 2017a; Ashraf et al. 2020). One of the methods to produce CH4 from CO2 is biomethanation (BM) through the hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis catalyzed by methanogenic archaea (Guneratnam et al. 2017). In comparison to the physicochemical methanation (Sabatier process), BM does not require high temperatures (35–70 °C) and can be performed at ambient pressure, which reduce the maintenance cost of biogas upgrading. Additionally, BM has a higher resistance to the contaminants (e.g., H2S and NH3) than the physicochemical process (Rachbauer et al. 2016). However, to perform the hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis the second substrate in form of hydrogen (H2) is required to produce CH4.

The sourcing of H2 for BM is one of the concerns regarding the sustainability of this process. Therefore, the source of H2 is typically related to the renewable energy sources (hydro, wind and solar power). These sources generate and increase the share of variable renewable electricity (VRE) in the electricity network. The buffer capacity to cover peaks from renewable energy production (esp. wind and solar power) is low, while its further development for higher energy storage capacity is still too expensive (Alitalo et al. 2015). Therefore, it has been proposed that the peaks of produced energy can be used for H2 production through water electrolysis avoiding energy squandering and enabling the grid balancing (Alfaro et al. 2018). From Norwegian perspective, where ca. 95% of electricity originates from hydropower, there is a significant correlation between the rain precipitation and electricity costs. Therefore, the use of excess energy for H2 production can potentially contribute to balance the grid that is mostly dependent on hydro power. In this context, BM opens new prospects in power-to-methane technology due to more efficient utilization of renewable energy. Although the BM offers economical and technical advantages, this method faces several challenges.

1.1 In-situ and ex-situ biomethanation

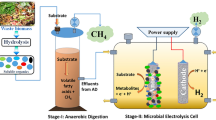

The fundamental challenge of BM is regarded to the low gas–liquid mass transfer rate of H2 (kLa), which hinders H2 uptake by methanogenic archaea for CO2 conversion (Kougias et al. 2017). Therefore, the different concepts of H2 injections were developed in the BM context such as in-situ, ex-situ and hybrid (combination of in-situ and ex-situ) (Angelidaki et al. 2018). The mostly studied in the last years is in-situ BM where the H2 is injected directly to the AD (Fig. 1a). This approach is regarded as low-cost since it avoids the additional infrastructure for biogas treatment by utilizing the AD reactor as the upgrading unit (Wahid et al. 2019). By this approach the CH4 concentrations around 99% could be achieved using continuous-stirred tank reactor (CSTR) (Wang et al. 2013). However, the operation of in-situ BM requires a rigorous monitoring and control of operational parameters. The direct injection of H2 to the AD causes the depletion in buffer capacity of CO2 that may cause the pH increase over 8.5 leading to the process disruptions and methanogenesis inhibition (Luo and Angelidaki 2012). Moreover, exogenous H2 supply leads to an increase in H2 partial pressure, which has a negative effect on particular anaerobic bacteria engaged in AD, possibly leading to process imbalance such as VFAs accumulation; hence, H2 in the liquid phase should be extensively utilized (Rusmanis et al. 2019). Previous studies, on the other hand, demonstrated that H2 was poorly soluble during in-situ BM, necessitating the use of advanced diffusion devices or extensive reactor stirring to generate small gas bubbles that can increase the contact area between gas and liquid (Bassani 2017; Voelklein et al. 2019).

To secure the stability of AD the ex-situ BM gained more attention in the recent years. The ex-situ BM occurs in a separate unit where H2 and biogas/CO2 are supplied as gaseous substrates, typically tailored to accommodate the hydrogenotrophic methanogens (Fig. 1b). This concept gives also more flexibility where the waste CO2 can be sourced from other processes. Due to that, compared to in-situ BM, the ex-situ BM usually gives a higher volumetric CH4 production rates with shorter gas retention time (Voelklein et al. 2019; Wahid et al. 2019). Additionally, the advantages such as biomass independent process and simpler biochemical process can be mentioned (Angelidaki et al. 2018).

The studies on ex-situ BM were performed in different reactor configurations such as CSTR, fixed bed, bubble column and trickle bed reactor (TBR). The previously reported results frequently indicate high effluent CH4 concentrations e.g., around 96% by using up-flow configurations with submerged filter or about 95% when employing CSTR (Luo and Angelidaki 2012; Bassani et al. 2017). However, the construction and maintenance of the additional ex-situ unit imposes additional costs while due to the poor H2 solubility the diffusion system and large volume of upgrading unit are required. CSTR systems frequently rely on high mixing speeds to increase kLa due to reduced gas bubble size and improved gas distribution. Yet, because of the high energy demand for mixing, upscaling is limited (Strübing et al. 2017). Ex-situ BM utilizing TBR, on the other hand, was considered to be the most promising because it may overcome process scale-up constraints. The TBR provides a large contact area between methanogenic archaea with gas phase, which enhances the conversion of H2 and CO2 into CH4 (Kougias et al. 2020). In this kind of configuration, about four orders of magnitude higher diffusion coefficient is achieved (Aryal et al. 2018). Besides, no additional energy for mixing is required, as in CSTR. In consequence, the number of studies on TBR in correlation to hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis has increased in the last years. Therefore, this review aims to sum up the recent findings regarding optimal operational conditions, configurations, performance, and microbiology of TBR in ex-situ BM concept.

2 Factors affecting ex-situ biomethanation

2.1 Stoichiometry

The ex-situ BM is based on the catabolic reaction between H2 and CO2 (molar ratio 4:1) that are converted into CH4 (Eq. 1). Additionally, CO2 serves as a carbon source for anabolic reaction of microbial growth that changes the molar ratio to ca. 3.7:1 (Eq. 2) when both anabolism and catabolism are accounted. However, the theoretical uptake for anabolic reaction is minor compared to catabolic reaction (Dupnock and Deshusses 2017). It has been found by Martin et al. (2013) that the experimental growth rate of hydrogenotrophic methanogen (Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus) was lower than theoretical.

During ex-situ BM, substrates are supplied in the gaseous form, and they exchange with the liquid phase, where, CO2 dissolves in the liquid phase according to Eq. 3. Depending on pH during the process, the CO2 solubility sharply increases around pH = 8.0 where the twofold higher CO2 concentration can be dissolved in the liquid phase compared to pH = 6.0. With increasing pH, the CO2 is represented by ionized forms such bicarbonate (HCO3−) and carbonate (CO32−) where the equilibrium point (pK) for CO2/HCO3− is pH = 6.3 while for HCO3−/CO32− is pH = 10.3 (Goldberg et al. 2002).

HCO3− is a key buffer in AD and plays an important role in pH control. Removal of HCO3− due to CO2 conversion (e.g., at high H2 supply H2/CO2 > 4) may lead to the pH increase above optimal level for microbial growth. Therefore, studies on ex-situ BM are frequently performed under strict pH control.

2.2 Reactors configuration

The frequently reported constraint in previous studies (regardless reactor’s design) was the gas–liquid mass transfer of H2 due to its low solubility (1.44 mg/kg of water at 50 °C) (Kolev 2011). In comparison to CO2, H2 is nearly 25 times less soluble in water (Sieborg et al. 2020). CSTR was commonly used for BM in recent years, where improvement on the gas liquid mass-transfer rate of H2 was the main focus. A number of studies on optimization of agitation, reactor shape, gas diffusion systems and impeller design were performed to enhance gas–liquid mass transfer by decreasing the gas bubble size (Orgill et al. 2013; Wahid and Horn 2021). For example, stirring speeds of up to 1500 rpm were demonstrated as efficient at the laboratory scale (Seifert et al. 2014). However, in return the accelerated agitation, special impeller design or reactor shape increase both the capital and operational costs of BM in CSTR, making it energy intensive.

In comparison to CSTR, TBR for ex-situ BM mitigates several problems that were faced with other configurations. The TBR is frequently used e.g., for hydrogen sulfide (H2S) removal from biogas where the number of different methods was developed in the last years (Naegele et al. 2013). The TBR configuration for ex-situ BM is based on the hydrogenotrophic methanogens activity that are immobilized as a biofilm on the packing material that results in a large contact area between biofilm and fed gases (Ashraf et al. 2020). The substrate gases are introduced most frequently under atmospheric pressure (or pressure between 1.5 and 9 bar) either downwards or upwards through the packing material (Fig. 2). Elevated pressure improves gas–liquid mass transfer in the reactor and is unlikely to affect BM (Ullrich et al. 2018). To ensure nutrients supplementation, the liquid substrate is continuously or periodically recirculated. Therefore, the operation of TBR does not require a high energy input for continuous mixing or bubbling. It has been shown that in comparison to other configurations, TBR has a higher specific CH4 production reaching up to 15.4 m3/(m3d)Footnote 1 (CSTR = 3.7 m3/(m3d); up-flow reactor 0.25 m3/(m3d)) (Bassani 2017; Strübing et al. 2017; Voelklein et al. 2019). At the same time, the quality of produced biomethane allows for the grid injection in most of cases.

2.3 Packing materials

Concerning the packing material, studies were performed using commercially available random packing carriers (i.e., glass ring, Bioflow 40, Hel-X) or structured packing (i.e., polyurethane foam) (Dupnock and Deshusses 2017; Ashraf et al. 2020; Dahl Jønson et al. 2020; Sieborg et al. 2020). Random packing was commonly used in the recent studies, that could be related to their clogging resistance (compared to e.g., polyurethane foam). The surface area of reported packing materials ranges from 300 m2/m3Footnote 2 (RFK 25 L type carrier, Strübing et al. (2017); Bioflow 40, Burkhardt et al. (2019); Hiflow rings type 15–7, Rachbauer et al. (2016)) to 859 m2/m3 (Hel-X bio carrier HXF12KLL, Strübing et al. (2017)). Generally, biofilm growth at large surface area is beneficial by providing high contact area between methanogenic archaea and substrate gases. In addition, the shape of the carrier is critical, e.g., glass rings, can halt part of recirculation liquid when positioned horizontally, preventing the even wetting of biofilm (Porté et al. 2019). Another example is clogging that was raised by Ashraf et al. (2020) when polyurethane foam was used during long term operation (200 days), caused by accumulated solids originating from used liquid media.

2.4 Operational conditions

Various operational conditions were tested during the TBR operation for ex-situ BM (Table 1). Most of the studies were performed in the laboratory scale, under working volumes ranging from < 1L to 61 L. Reactors were run mostly at thermophilic (ca. 55 °C) (Strübing et al. 2017, 2018, 2019; Porté et al. 2019; Ashraf et al. 2020; Dahl Jønson et al. 2020; Sieborg et al. 2020) or mesophilic (ca. 37 °C) (Burkhardt and Busch 2013; Burkhardt et al. 2015, 2019; Rachbauer et al. 2016; Dupnock and Deshusses 2017) conditions. The operating temperature was shown to be crucial for the efficiency of BM. Typically, higher methane production rates were observed for reactors operating at thermophilic temperatures due to increased microbial growth rates (Angelidaki et al. 2018). Nonetheless, Rachbauer et al. (2016) reported an output gas with a CH4 content (> 96%) using a mesophilic TBR in a long-term experiment (8 months), demonstrating that a long adaptation period affects reactor performance regardless of temperature conditions.

2.4.1 Gas loading rates

Performed studies reported wide ranges of influent gas loading rates. The gas loading rates of the feed gases vary between 1.8 and 214.9 m3/(m3d) though most studies used gas loading rates in the range of 5–16 m3/(m3d) (Table 1). Higher loadings of around 70 m3/(m3d) were used by Strübing et al. (2019, 2018, 2017) while Dupnock and Deshusses (2017) studied extreme high flow rates between 151.4 and 214.9 m3/(m3d). Depending on the operational conditions, the process performance of the BM was significantly influenced by the applied gas loading rate. However, no clear correlation can be established based on the applied gas loading rate and used packing materials.

2.4.2 Reactors inoculation

To inoculate TBR for ex-situ BM, digestate from biogas reactors (Rachbauer et al. 2016; Dahl Jønson et al. 2020) or sludge from wastewater treatment plants (Burkhardt and Busch 2013; Burkhardt et al. 2015, 2019; Strübing et al. 2017, 2018, 2019) were mainly used. Often, these cultures were enriched (containing a high abundance of hydrogenotrophic methanogens) to shorten the lag phase or adaptation period. Different inoculation procedures were reported in the literature while most studies performed inoculation by recirculating the liquid inoculum for a certain period of time. Some reported short recirculation time (2 h) (Ashraf et al. 2020; Dahl Jønson et al. 2020; Sieborg et al. 2020), while Porté et al. (2019) recirculated inoculum for 24 h. Much longer inoculation period (72 h) was reported by Burkhardt et al. (2019) and Rachbauer et al. (2016). In most cases, substrate gases were introduced after inoculation period, though Strübing et al. (2019, 2018, 2017) supplied substrate gases during the inoculation period.

2.4.3 Nutrient requirements

Continuous supplementation of nutrients to the microbes in TBR is crucial to maintain the stability of the process. In recent years, the media used for ex-situ BM in TBR can be categorized into synthetic and non-synthetic. Non-synthetic liquid media originated mostly from digested wastewater sludge (Strübing et al. 2017, 2018, 2019), digestate from biogas plant (Porté et al. 2019) and pasteurized cow manure (Ashraf et al. 2020; Dahl Jønson et al. 2020; Sieborg et al. 2020). The possibility to use non-synthetic and rather easily available media is a strong advantage of this process increasing its sustainability. However, the non-synthetic media require pretreatment to prevent the growth of unintended microorganisms, that can potentially produce biogas through the acetoclastic pathway or use gas substrates e.g., to produce acetate through homoacetogenesis. In the literature, several pre-treatment methods have been published, for example, Porté et al. (2019) incubated the digestate for more than 3 months under thermophilic conditions to minimize biogas generation from organic matter in the medium. Strübing et al. (2019, 2018, 2017) flushed the digested sewage sludge repeatedly with nitrogen and sieved it (100 µm) to remove the solid particles before use. Pasteurization at 70 °C was performed by Ashraf et al. (2020), Sieborg et al. (2020) and Dahl Jønson et al. (2020) to inhibit bacterial activity in cow manure. The supplementation with synthetic media was described by Strübing et al. (2018, 2017) following the procedure adopted by Seifert et al. (2014). Application of mineral buffer solution, as e.g., phosphate buffer was also performed to maintain pH of medium (Dupnock and Deshusses 2017; Strübing et al. 2017, 2018; Dahl Jønson et al. 2020). In these studies, buffer solution was supplied when necessary without any fixed rhythm. Instead of using phosphate buffer, Porté et al. (2019) neutralized medium twice a week with HCl and introduced it back into the reactor to stabilize the pH value. Consequently, different procedures applied in the previous studies had also focused on a wide pH range that spanned from 7.0 up to around 8.6.

The frequency of nutrients supplementation in TBR varied between the studies. Often irregular nutrient supply was reported (Rachbauer et al. 2016; Ashraf et al. 2020; Dahl Jønson et al. 2020). This indicates that the studies optimizing the liquid phase exchange were not comprehensive enough, making it difficult to compare findings from different studies.

2.5 TBR performance

In this review, the performance of TBR from previous studies were compared based on the efficiency of CO2 and H2 conversion into CH4 and the effluent CH4 content. In general, most studies reported a nearly full conversion rate (around 99%) while few studies reported slightly lower conversion values ranging between 97–98% (Table 1). The high conversion rate was correlated with high CH4 content in the effluent gas in nearly all previous studies (> 95%). However, in these calculations, some studies used the N2 in the experiments to mimic the CH4 in the supplied gas (Ashraf et al. 2020; Dahl Jønson et al. 2020). Similar addition of N2 was also performed by Sieborg et al. (2020) where the CH4 content without recognition of the added N2 as CH4 was 67.1% in the effluent gas. However, without reported conversion, it is not possible to relate this information with two previously mentioned studies.

On the other hand, Dupnock and Deshusses (2017) reported a very low conversion rate with the effluent CH4 content of 44%. These results were related to the extremely high gas loading applied to the reactor (151.4 m3/(m3d)–214.9 m3/(m3d)) that is about 3 times higher than the loadings reported by others. Extreme gas loading led to a decrease in product gas purity and low conversion efficiency that can be caused by the shear force impacted on biofilm resulting in its detachment. Therefore, the optimum gas loading rate should be determined according to the packing material used. A study by Strübing et al. (2019, 2018, 2017) obtained good results with nearly full conversion when high gas loading (> 16 m3/(m3d)) was used, showing that higher loadings can be adapted in the TBR for BM. On the other hand, extreme high loadings as used in Dupnock and Deshusses (2017) seem to be too challenging for this reactor configuration.

Regarding to H2 injection configurations, the literature comparing concurrent and counter-current configurations are scarce. Therefore, the proper validation of the most appropriate configuration is not currently possible. To our knowledge, only Porté et al. (2019) compared these two configurations indicating comparable results for both configurations (CH4 content—97.6% for concurrent and 97.8% for counter-current). However, this study was performed using only one kind of packing material (glass rings) and relatively low gas loading rate (up to 11.6 m3/(m3d)).

The use of different liquid phases with a wide pH range (from 7.0 up to 8.6) had no significant influence on the purity of the effluent gas. Comparable CH4 content with an average of 97 to 98% were observed (Fig. 3). Similar observations have been reported when different operating temperatures were tested (mesophilic vs. thermophilic), as the performance of the reactors were comparable. Though, the microbial communities and the hydrogenotrophic methanogens differ because of temperature.

2.6 Typical process disturbances

The TBR for ex-situ BM offers many advantages compared to different configurations. However, the difficulties regarding several issues were previously reported. The most common difficulties are related to the establishment of archaea in the TBR that leads to a non-efficient CH4 production or acetate synthesis (homoacetogenesis) (Eq. 4) (Logroño et al. 2020). The acetate accumulation was previously reported by e.g., Kougias et al. (2017). The acetate synthesis during the process leads to the pH decrease and lower CH4 production. Therefore, the appropriate operational conditions are critical to manage microbiota towards selective CH4 production.

Another problem typically connected with TBR operation is clogging, that is caused by the uncontrolled biomass growth on the packing material. Clogging causes significant technical problems leading to the process performance limitation (Burkhardt et al. 2019). Due to the clogging, the packing material needs to be replaced, that in case of e.g., foam-like packing requires a new acclimatization of microbiota with packing material (Alfaro et al. 2018). Aside from clogging, the high loading gas supplied to the TBR may cause the detachment of the biofilm developed on the packing material leading to the biomass wash out.

Based on the Eq. 1 the ex-situ BM in addition to CH4 produces H2O as a co-product. The H2O production during TBR causes the dilution of the liquid phase in TBR. In consequence, it causes the dilution of e.g., trace elements and nutrients required for microbial growth that need to be balanced during the reactor operation.

3 Microbiology of ex-situ biomethanation

The ex-situ BM process is based on the biological activity of hydrogenotrophic methanogens (archaea) that use CO2 and H2 as substrates. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens are typically present in the regular AD where they theoretically contribute to around 30% of CH4 production (70% is accounted for acetoclastic methanogens) (Sawayama et al. 2004). The hydrogenotrophic methanogens were found to be less sensitive to the presence of ammonia than the acetoclastic methanogens, leading to an increase in their share at elevated ammonia presence during the regular AD (Angenent et al. 2002; Sposob et al. 2020). This trait of hydrogenotrophic methanogens can potentially facilitate the use of other ammonia-rich and non-synthetic nutrients sources or enhance the system tolerance on ammonia presence in biogas as the feedstock to ex-situ BM.

Based on the previous studies, it has been found that the ex-situ BM conditions selectively enriched hydrogenotrophic methanogens leading to their predominance. Therefore, the information about bacteria and their role in ex-situ BM is rather limited. Although, previous studies on bacterial communities revealed that the phyla Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes typically predominate in TBR (Dupnock and Deshusses 2017; Kougias et al. 2017; Porté et al. 2019; Ashraf et al. 2020). Several bacterial taxa from phyla Firmicutes (mainly Clostridia) were suspected to be responsible for homoacetogenesis (Logroño et al. 2020). Also, previous research indicated Clostridia members to be abundant in TBR biofilm and liquid media, while acetate-utilizing bacteria prevailed in liquid samples (Porté et al. 2019). However, their further identification at e.g., genus level was challenging to achieve. The two main orders of hydrogenotrophic methanogens such as Methanobacteriales and Methanomicrobiales were found characteristic for ex-situ BM (Table 2). It has been suggested that their dominance during BM systems is regardless the operating temperature (Logroño et al. 2020).

Order Methanobacteriales is widespread and known for mediating the hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis both under mesophilic and thermophilic conditions (Karakashev et al. 2005). In the last years different species of Methanobacteriales were identified. For example Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus was frequently reported in the case of thermophilic ex-situ BM (Martin et al. 2013; Kougias et al. 2017). Furthermore, they are capable to thrive in high H2S concentrations conditions (Kaster et al. 2011). Therefore, this methanogen was widely used for bioaugmentation of ex-situ BM, similarly as Methanothermobacter marburgensis expressing their stable performance over the time. Additionally, some of the hydrogenotrophic methanogens such as Methanobrevibacter arboriphilus express the capability to survive in the oxygen (O2) exposures up to 3 days enhancing the system ability to recover (Dupnock and Deshusses 2017).

The second order present during the ex-situ BM, Methanomicrobiales, is usually represented by a lower relative share in comparison to the Methanobacteriales. Genera of Methanoculleus and Methanospirillum were previously reported in context of ex-situ BM. Methanoculleus has also been reported in high salt and ammonia AD processes (maize and manure as a substrate) (Maus et al. 2012; Dahl Jønson et al. 2020). The lower presence of Methanomicrobiales, especially Methnospirillum can be related to the fact that no thermophilic Methanospirillum genus has been identified so far while most of the previous studies operated at thermophilic conditions (Jain et al. 2020). Although, their presence was previously reported in mesophilic AD reactors treating cattle and pig manure.

4 Techno-economic analysis

There has been little research focus on the cost analysis of the TBR in the power-to-methane concept; therefore, this section will assess the relevant factors related to the economy of power-to-methane technology using BM reactors in general.

4.1 Power-to-methane with BM reactor

To our knowledge, only one study, Bekkering et al. (2020), used TBR as an ex-situ BM reactor in estimating the cost of farm-scale power-to-methane technology. The authors compared the costs of four different scenarios in the study: (a) without BM, biogas is upgraded using membrane technology, (b) with BM, (c) BM combined with membrane upgrading, and (d) BM combined with membrane upgrading with surplus renewable electricity. Scenario (a) had the lowest renewable gas production costs, whereas scenarios (b–d) had higher energy efficiencies and environmental benefits (due to the consumption of renewable energy). The higher costs of BM scenarios are primarily the result of electrolysis. The investment cost for ex-situ TBR (including compressor) for a 500 Nm3 h−1 biogas production unit was estimated to be 1.5 × 106 €.

The production cost of BM for 5 MW plant size is slightly higher than catalytic methanation, while at 110 MW plant size, these costs are about 2.5 times higher than for catalytic methanation (Götz et al. 2016). For both processes, the costs are heavily dependent on the electrolyzer investment cost. The cost of the BM process in 2017 was around 1200 € kWel−1 (related to the electrical power input of electrolyzer) and is expected to drop to 300 € kWel−1 in 2050 (Golling et al. 2017). In 2030, the cost of BM is predicted to fall to 700 € kWel−1. The cost reduction could be due to lower cost of electrolyzer and economy scale with the development of the technology (Golling et al. 2017). Hidalgo and Martín-Marroquín (2020) mentioned that the investment costs for electrolysis and methanation technologies are expected to fall from > 1000 € kWel−1 to about 500 € kWel−1 in the future. The decrease in the investment cost clearly indicates that the market implementation of the power-to-methane concept is ongoing.

Consideration of environmental effects during the economic feasibility assessment of BM is crucial. Bekkering et al. (2020) reported that GHG savings improved better with BM technology than without. It is expected that the cost of energy may be at the similar level of the cost of natural gas if CO2 emission saving in included or if the CO2 emitted from natural gas is taxed. Another point to be considered is that BM can minimize the expansion of electricity grid infrastructure and raise the share of green energy in the transportation and heating sector. In this light, BM itself plays an important part in the realization of the ambitious transition of the energy system (Götz et al. 2016).

4.2 Electrolysis

Water electrolysis is one of many H2 processing technologies that produces high purity H2 in an environmentally friendly manner (Kumar and Himabindu 2019). The production costs of H2 from water electrolysis are influenced by various technical and economic factors, with CAPEX requirements, conversion efficiency, electricity costs and annual operating hours being the most important. The cost of producing H2 alone is estimated to be 0.09 € kWh−1, which is higher than the cost of conventional physicochemical biogas upgrading by CO2 removal (0.07 € kWh−1) (Angelidaki et al. 2018).

Currently, there are three water electrolysis technologies available: alkaline electrolysis (AE), polymer electrolyte membrane electrolysis (PEM) and solid oxide electrolysis (SOE) (Hosseini and Wahid 2016; Gorre et al. 2020). CAPEX requirements for AE are in the range of 416–1165 € kWe−1 and 916–1498 € kWe−1 for PEM electrolyzers, while estimates for SOEC electrolyzers range across 2230–4660 € kWe−1. Further reduction in CAPEX is projected in the future (Fig. 4). The main reasons for the reduction are related to the increase in automation and production capabilities, together with the enhancement in electrolyzers technology due to development of power-to-gas. The operation and maintenance (O&M) costs shared about 9% of the total H2 production cost.

CAPEX of different types of electrolyzers (LT–long-term, AE–Alkaline electrolysis, PEM—polymer electrolyte membrane electrolysis, SOE—solid oxide electrolysis. CAPEX represents system costs, including power electronics, gas conditioning and balance of plant; CAPEX ranges reflect different system sizes and uncertainties in future estimates)

At present, AE technology is more suitable for large scale implementation because of the cost and maturity (Brauns and Turek 2020; Hu et al. 2020). However, the main drawbacks are low current densities, corrosion and limitation when working in dynamic condition (e.g. slow start-up and loading response) (Hosseini and Wahid 2016; Dutta and Hussain 2020; Grimm et al. 2020). On the other hand, the PEM technology is more efficient and flexible to handle fluctuating input currents but is restricted by expensive materials cost, short life span and complexity due to high operating pressure (Hosseini and Wahid 2016; Brauns and Turek 2020; Dutta and Hussain 2020). SOE is the latest development in water electrolysis technology. Positive aspects of SOE include high electrical efficiency, low material cost and possibility to operate in reverse mode as fuel cell or in co-electrolysis way (Hidalgo and Martín-Marroquín 2020). Nevertheless, the technology has a limited lifetime due to thermal cycles (Pääkkönen et al. 2018; Dutta and Hussain 2020). Future cost reductions, increased lifetime and improved efficiency in these technologies may be realized through the development of new materials and manufacturing processes.

4.3 H2 storage and transportation

Typically, electrolysis can be performed more dynamically than the operation of methanation reactor. As a result, H2 storage is needed. If the cost of H2 storage is considered, it is the second main contributor to the investment cost of a power-to-methane plant (Götz et al. 2016). Currently, gaseous storage at different pressure levels are mainly used at large BM plants (Gorre et al. 2020). The costs of storage may vary between 375 € kg−1 for 50 bar and 490 € kg−1 for 200 bar (Gorre et al. 2020). The size of H2 storage system depends on the dynamic behavior of methanation and the profile of electrical input of electrolyzer (Götz et al. 2016; Gorre et al. 2020). For example, larger H2 storage is required for full load operation, while smaller storage is needed for dynamic operation. Besides, electrolyzer operating in a smaller number of full-load hours may greatly reduce the investment cost. Dynamic operation is the best option in term of cost, however, the variability in H2 input may affect the process performance of the BM reactor because the anaerobic microbes are sensitive to changes. Further research is crucial to examine the response of anaerobic microbes towards intermittent H2 supply.

The cost for transportation could be close to zero if the H2 can be utilized directly to where it is produced. Though, if the H2 has to be transported for long distance, the costs of transmission and distribution could be three times as large as the cost of H2 production (Birol 2019). H2 has a low energy density, meaning that it is expensive to transport H2 over long distances. Different types of H2 transportation methods are available, including cryogenic liquid tankers, pressurized H2 tube trailers and gas pipelines. The selection of economical H2 transportation varies based on the distance and amounts of H2. For short distances (< 500 km) and small amounts, liquid H2 transport by trucks is the best option, meanwhile, pipelines and ship are the potential option for long distances (> 1000 km) and transport of large amounts of H2 (Nazir et al. 2020). The estimated cost of H2 distribution for 500 km in 2030 using pipelines and liquid H2 trucks is below 0.5 € kg−1 while around 1.7 € kg−1 when H2 is compressed and transported by trucks. However, the choice of H2 transportation also depends on the required form of H2 (gases or liquid) at the utilization purpose.

4.4 Economic potential of by-products

By-products such as O2 or heat generated during electrolysis and recovered from AD effluent could be valorized to increase the economic viability of BM (Zauner et al. 2018; Bekkering et al. 2020; Hidalgo and Martín-Marroquín 2020). O2 for example can be sold (price of O2 is 50 € t−1) for industrial use (Zauner et al. 2018). Another option is to use it for aeration process (e.g., nitrification) in the wastewater treatment plant or for desulfurization of biogas (Götz et al. 2016). Though, additional cost for liquefaction of O2 for transportation purposes and the intermittent O2 production (based on electrolyzer operation) need to be considered. In this case, direct utilization of O2 at the electrolyzer site could be the best scenario. The waste heat from BM can be utilized for heating the digester or drying the digestate (Bekkering et al., 2020; Gorre et al., 2020). Waste heat recovery should be considered wherever possible in order to increase the resource and overall process efficiency.

5 Sources of CO2

The sources of CO2 for BM can originate from fossil power plants, biomass, industrial product gasses or ambient air (Schiebahn et al. 2015; Gorre et al. 2020; Hidalgo and Martín-Marroquín 2020). CO2 captured from fossil power plants are widely investigated in the context of carbon capture and storage (CCS). Several separation technologies are available including adsorption, membrane separation, chemical and physical absorption, and cryogenic separation. The related costs are calculated around 20–60 € tCO2−1. While, large amounts of CO2 can be extracted from fossil power plants, the fact that CO2 is not biogenic makes it difficult to be classified as the product of renewable power CH4 (Schiebahn et al. 2015). Fermentation of biomass to produce biogas or bioethanol generates CO2 as by-products and thus, no extra energy or cost involved for producing biogenic CO2. CO2 from raw biogas can be used directly in BM without the need of CO2 separation (Schiebahn et al. 2015).

The energy and industry sectors contribute to more than one third of global CO2 emissions (Hidalgo and Martín-Marroquín 2020). Thus, CO2 from these sectors can serve as a potential substrate for BM decreasing the CO2 emissions. CO2 separation technology in industrial processes is technically feasible. The most relevant industries are cement and steel, due to the high CO2 generations (Schiebahn et al. 2015). Combining the biomass gasification technology with power-to-methane could be an interesting approach to increase the availability of H2 and CO2 for BM (Götz et al. 2016). The gases (CO, CO2 and H2) produced from the biomass gasification process could be used as substrates for BM, together with H2 generated from electrolysis. The integration of biomass gasification and power-to-methane during the steel production process has been already evaluated by Rosenfeld et al. (2020). During the steel production, three gases such as coke oven gas (COG), blast furnace gas (BFG) and basic oxygen furnace gas (BOFG) are produced. COG contains a high share of CH4 and H2 while BFG and BOFG consist of CO2, CO and N2 (Rosenfeld et al. 2020). These gases can be indicated as another substrate source for BM. Besides steel industry, other relevant CO2 or CO sources are from cement manufacturing and chemical industry (Baier et al. 2018; Hidalgo and Martín-Marroquín 2020). However, further studies on the profitability of such system in terms of mass and energy balance, economy and CO2 reduction are needed.

CO2 from ambient air can be separated using strong alkali such as potassium or sodium hydroxide. This process has the advantage of being able to supply biogenic CO2 without relying on spatially accessible CO2 sources. Furthermore, there is no requirement for CO2 transportation. According to the literature, the cost of CO2 generated by air capture varies between 100 and 1000 € tCO2−1 (Schiebahn et al. 2015; Bos et al. 2020). Keith et al. (2018), on the other hand, reported a lower levelized cost per ton CO2 captured from the atmosphere, ranging from 78 to 193 € tCO2−1.

6 Perspectives

Since the TBR was quite recently applied for ex-situ BM, the understanding of the process is limited specifically regarding optimal conditions and maximum performance. Due to that, further work focusing on operational parameters optimization (e.g., gas loading rate, hydraulic retention time, pH) and packing materials should be performed to increase the process productivity and describe its limitations.

TBR configuration also has its drawbacks for which solutions can be found in the future such as: bacterial contamination (homoacetogenesis), clogging and H2O production. Additionally, better understanding of ex-situ BM could be achieved through the mathematical modeling of hydrogenotrophic methanogens at TBR. However, so far, the modeling approaches regarding hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis are scarce.

Appropriate optimization of the process will provide an answer to the mass and energy balance of this process and its economic feasibility. At the same time, further development of electrolyzers for H2 production is expected that could potentially decrease the price of H2, which is an economically crucial factor for the process. The future answers to these considerations will probably facilitate the scale up of ex-situ BM using TBR and its application at the full-scale AD plants.

7 Conclusions

Ex-situ biomethanation is one of the most promising solutions addressing the power-to-methane concept that is going to significantly develop in the next years. In this review the attention was given to TBR as the most efficient for this application describing its principals, operational conditions, performance, and microbiology.

From an economic point‐of‐view, the prospects of power-to-methane will be dependent on the reduction of H2 costs and developments in electrolyzers technology. Therefore, the related costs influencing power-to-methane technology with BM reactor such as electrolyzers and H2 storage and transportation were also discussed in this work. Furthermore, we explored the possibility of using CO2 generated from various sources as an influent substrate for BM.

Notes

volume of feed gas per volume of reactor per day.

surface area per packing material volume.

References

Alfaro N, Fdz-Polanco M, Fdz-Polanco F, Díaz I (2018) Evaluation of process performance, energy consumption and microbiota characterization in a ceramic membrane bioreactor for ex-situ biomethanation of H2 and CO2. Bioresour Technol 258:142–150

Alitalo A, Niskanen M, Aura E (2015) Biocatalytic methanation of hydrogen and carbon dioxide in a fixed bed bioreactor. Bioresour Technol 196:600–605

Angelidaki I, Treu L, Tsapekos P et al (2018) Biogas upgrading and utilization: current status and perspectives. Biotechnol Adv 36:452–466

Angenent LT, Sung S, Raskin L (2002) Methanogenic population dynamics during startup of a full-scale anaerobic sequencing batch reactor treating swine waste. Water Res 36:4648–4654

Aryal N, Kvist T, Ammam F et al (2018) An overview of microbial biogas enrichment. Bioresour Technol 264:359–369

Ashraf MT, Sieborg MU, Yde L et al (2020) Biomethanation in a thermophilic biotrickling filter—pH control and lessons from long-term operation. Bioresour Technol Reports 11:100525

Baier J, Schneider G, Heel A (2018) A cost estimation for CO2 reduction and reuse by methanation from cement industry sources in Switzerland. Front Energy Res 6:5

Barragán-Escandón A, Ruiz JMO, Tigre JDC, Zalamea-León EF (2020) Assessment of power generation using biogas from landfills in an equatorial tropical context. Sustain 12:2669

Bassani I (2017) Hydrogen assisted biological biogas upgrading. Technical University of Denmark, DTU Environment

Bassani I, Kougias PG, Treu L et al (2017) Optimization of hydrogen dispersion in thermophilic up-flow reactors for ex situ biogas upgrading. Bioresour Technol 234:310–319

Bekkering J, Zwart K, Martinus G et al (2020) Farm-scale bio-power-to-methane: comparative analyses of economic and environmental feasibility. Int J Energy Res 44:2264–2277

Birol F (2019) The future of hydrogen: seizing today’s opportunities. IEA for the G20, 82-83, Japan

Bos MJ, Kersten SRA, Brilman DWF (2020) Wind power to methanol: Renewable methanol production using electricity, electrolysis of water and CO2 air capture. Appl Energy 264:114672

Brauns J, Turek T (2020) Alkaline water electrolysis powered by renewable energy: a review. Processes 8:248

Burkhardt M, Busch G (2013) Methanation of hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Appl Energy 111:74–79

Burkhardt M, Koschack T, Busch G (2015) Biocatalytic methanation of hydrogen and carbon dioxide in an anaerobic three-phase system. Bioresour Technol 178:330–333

Burkhardt M, Jordan I, Heinrich S et al (2019) Long term and demand-oriented biocatalytic synthesis of highly concentrated methane in a trickle bed reactor. Appl Energy 240:818–826

Dahl Jønson B, Ujarak Sieborg M, Tahir Ashraf M et al (2020) Direct inoculation of a biotrickling filter for hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis. Bioresour Technol 318:124098

Dupnock TL, Deshusses MA (2017) High-performance biogas upgrading using a biotrickling filter and hydrogenotrophic methanogens. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 183:488–502

Dutta S, Hussain CM (2020) Sustainable Fuel Technologies Handbook. Academic Press

Gasunie NVN (1980) Physical properties of natural gases. NV Nederlandse Gasunie

Goldberg RN, Kishore N, Lennen RM (2002) Thermodynamic quantities for the ionization reactions of buffers. J Phys Chem Ref Data 31:231

Golling C, Heuke R, Seidl H, Uhlig J (2017) Roadmap power to gas

Gorre J, Ruoss F, Karjunen H et al (2020) Cost benefits of optimizing hydrogen storage and methanation capacities for Power-to-Gas plants in dynamic operation. Appl Energy 257:113967

Götz M, Lefebvre J, Mörs F et al (2016) Renewable power-to-gas: a technological and economic review. Renew Energy 85:1371–1390

Grimm A, de Jong WA, Kramer GJ (2020) Renewable hydrogen production: a techno-economic comparison of photoelectrochemical cells and photovoltaic-electrolysis. Int J Hydrogen Energy 45:22545–22555

Guneratnam AJ, Ahern E, FitzGerald JA et al (2017) Study of the performance of a thermophilic biological methanation system. Bioresour Technol 225:308–315

Hidalgo D, Martín-Marroquín JM (2020) Power-to-methane, coupling CO2 capture with fuel production: an overview. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 132:110057

Hosseini SE, Wahid MA (2016) Hydrogen production from renewable and sustainable energy resources: promising green energy carrier for clean development. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 44:4110–4131

Hu G, Chen C, Lu HT et al (2020) A review of technical advances, barriers, and solutions in the power to hydrogen (P2H) roadmap. Engineering 6:1364–1380

IEA (2020) Outlook for biogas and biomethane

Jain KA, Suryawanshi PC, Chaudhari AB (2020) Hydrogenotrophic methanogen strain of Methanospirillum from anaerobic digester fed with agro-industrial waste. Biologia 76(1):255–266

Jensen MB, Strübing D, de Jonge N et al (2019) Stick or leave–pushing methanogens to biofilm formation for ex situ biomethanation. Bioresour Technol 291:121784

Jones SW, Karpol A, Friedman S et al (2020) Recent advances in single cell protein use as a feed ingredient in aquaculture. Curr Opin Biotechnol 61:189–197

Karakashev D, Batstone DJ, Angelidaki I (2005) Influence of environmental conditions on methanogenic compositions in anaerobic biogas reactors. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:331–338

Kaster AK, Goenrich M, Seedorf H, et al (2011) More than 200 genes required for methane formation from H2 and CO2 and energy conservation are present in methanothermobacter marburgensis and methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus. Archaea

Keith DW, Holmes G, Angelo DS, Heidel K (2018) A process for capturing CO2 from the atmosphere. Joule 2:1573–1594

Kim S, Choi K, Chung J (2013) Reduction in carbon dioxide and production of methane by biological reaction in the electronics industry. Int J Hydrogen Energy 38:3488–3496

Kolev NI (2011) Solubility of O2, N2, H2 and CO2 in water. In: Multiphase Flow Dynamics 4

Kougias PG, Campanaro S, Treu L et al (2017) A novel archaeal species belonging to Methanoculleus genus identified via de-novo assembly and metagenomic binning process in biogas reactors. Anaerobe 46:23–32

Kougias PG, Tsapekos P, Treu L et al (2020) Biological CO2 fixation in up-flow reactors via exogenous H2 addition. J Biotechnol 319:1–7

Kumar SS, Himabindu V (2019) Hydrogen production by PEM water electrolysis–A review. Mater Sci Energy Technol 2:442–454

Logroño W, Popp D, Kleinsteuber S et al (2020) Microbial resource management for ex situ biomethanation of hydrogen at alkaline ph. Microorganisms 8:614

Luo G, Angelidaki I (2012) Integrated biogas upgrading and hydrogen utilization in an anaerobic reactor containing enriched hydrogenotrophic methanogenic culture. Biotechnol Bioeng 109:2729–2736

Martin MR, Fornero JJ, Stark R, et al (2013) A single-culture bioprocess of methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus to upgrade digester biogas by CO2-to-CH4 conversion with H2. Archaea 2013

Maus I, Wibberg D, Stantscheff R et al (2012) Complete genome sequence of the hydrogenotrophic, methanogenic archaeon Methanoculleus bourgensis strain MS2T, isolated from a sewage sludge digester. J Bacteriol 194:5487–5488

Naegele H-J, Lindner J, Merkle W et al (2013) Effects of temperature, pH and O2 on the removal of hydrogen sulfide from biogas by external biological desulfurization in a full scale fixed-bed trickling bioreactor (FBTB). Int J Agric Biol Eng 6:69–81

Nazir H, Muthuswamy N, Louis C et al (2020) Is the H2 economy realizable in the foreseeable future? Part II: H2 storage, transportation, and distribution. Int J Hydrogen Energy 45:20693–20708

Orgill JJ, Atiyeh HK, Devarapalli M et al (2013) A comparison of mass transfer coefficients between trickle-bed, hollow fiber membrane and stirred tank reactors. Bioresour Technol 133:340–346

Pääkkönen A, Tolvanen H, Rintala J (2018) Techno-economic analysis of a power to biogas system operated based on fluctuating electricity price. Renew Energy 117:166–174

Petersson A, Wellinger A (2009) Biogas upgrading technologies–developments and innovations. IEA Bioenergy 20:1–19

Porté H, Kougias PG, Alfaro N et al (2019) Process performance and microbial community structure in thermophilic trickling biofilter reactors for biogas upgrading. Sci Total Environ 655:529–538

Rachbauer L, Voitl G, Bochmann G, Fuchs W (2016) Biological biogas upgrading capacity of a hydrogenotrophic community in a trickle-bed reactor. Appl Energy 180:483–490

Rosenfeld DC, Böhm H, Lindorfer J, Lehner M (2020) Scenario analysis of implementing a power-to-gas and biomass gasification system in an integrated steel plant: a techno-economic and environmental study. Renew Energy 147:1511–1524

Rusmanis D, Shea RO, Wall DM et al (2019) Biological hydrogen methanation systems–an overview of design and efficiency efficiency. Bioengineered 10:604–634

Savvas S, Donnelly J, Patterson T et al (2017a) Biological methanation of CO2 in a novel biofilm plug-flow reactor: a high rate and low parasitic energy process. Appl Energy 202:238–247

Savvas S, Donnelly J, Patterson TP et al (2017b) Closed nutrient recycling via microbial catabolism in an eco-engineered self regenerating mixed anaerobic microbiome for hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis. Bioresour Technol 227:93–101

Sawayama S, Tada C, Tsukahara K, Yagishita T (2004) Effect of ammonium addition on methanogenic community in a fluidized bed anaerobic digestion. J Biosci Bioeng 97:65–70

Schiebahn S, Grube T, Robinius M et al (2015) Power to gas: technological overview, systems analysis and economic assessment for a case study in Germany. Int J Hydrogen Energy 40:4285–4294

Seifert AH, Rittmann S, Herwig C (2014) Analysis of process related factors to increase volumetric productivity and quality of biomethane with Methanothermobacter marburgensis. Appl Energy 132:155–162

Sieborg MU, Jønson BD, Ashraf MT et al (2020) Biomethanation in a thermophilic biotrickling filter using cattle manure as nutrient media. Bioresour Technol Reports 9:100391

Sposob M, Moon H-S, Lee D et al (2020) Comprehensive analysis of the microbial communities and operational parameters of two full-scale anaerobic digestion plants treating food waste in South Korea: seasonal variation and effect of ammonia. J Hazard Mater 398:122975

Strübing D, Huber B, Lebuhn M et al (2017) High performance biological methanation in a thermophilic anaerobic trickle bed reactor. Bioresour Technol 245:1176–1183

Strübing D, Moeller AB, Mößnang B et al (2018) Anaerobic thermophilic trickle bed reactor as a promising technology for flexible and demand-oriented H2/CO2 biomethanation. Appl Energy 232:543–554

Strübing D, Moeller AB, Mößnang B et al (2019) Load change capability of an anaerobic thermophilic trickle bed reactor for dynamic H2/CO2 biomethanation. Bioresour Technol 289:121735

Ullrich T, Lindner J, Bär K et al (2018) Influence of operating pressure on the biological hydrogen methanation in trickle-bed reactors. Bioresour Technol 247:7–13

Voelklein MA, Rusmanis D, Murphy JD (2019) Biological methanation: Strategies for in-situ and ex-situ upgrading in anaerobic digestion. Appl Energy 235:1061–1071

Wahid R, Horn SJ (2021) The effect of mixing rate and gas recirculation on biological CO2 methanation in two-stage CSTR systems. Biomass Bioenergy 144:105918

Wahid R, Mulat DG, Gaby JC, Horn SJ (2019) Effects of H2:CO2 ratio and H2 supply fluctuation on methane content and microbial community composition during in-situ biological biogas upgrading. Biotechnol Biofuels 12:104

Wang W, Xie L, Luo G et al (2013) Performance and microbial community analysis of the anaerobic reactor with coke oven gas biomethanation and in situ biogas upgrading. Bioresour Technol 146:234–239

Zauner A, Böhm H, Rosenfeld DC, Tichler R (2018) Innovative large-scale energy storage technologies and Power-to-Gas concepts after optimization

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway through grant 257622 (Bio4Fuels).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sposob, M., Wahid, R. & Fischer, K. Ex-situ biological CO2 methanation using trickle bed reactor: review and recent advances. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 20, 1087–1102 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-021-09589-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-021-09589-7