Abstract

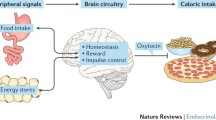

Obesity and its associated metabolic disorders are growing health concerns in the US and worldwide. In the US alone, more than two-thirds of the adult population is classified as either overweight or obese [1], highlighting the need to develop new, effective treatments for these conditions. Whereas the hormone oxytocin is well known for its peripheral effects on uterine contraction during parturition and milk ejection during lactation, release of oxytocin from somatodendrites and axonal terminals within the central nervous system (CNS) is implicated in both the formation of prosocial behaviors and in the control of energy balance. Recent findings demonstrate that chronic administration of oxytocin reduces food intake and body weight in diet-induced obese (DIO) and genetically obese rodents with impaired or defective leptin signaling. Importantly, chronic systemic administration of oxytocin out to 6 weeks recapitulates the effects of central administration on body weight loss in DIO rodents at doses that do not result in the development of tolerance. Furthermore, these effects are coupled with induction of Fos (a marker of neuronal activation) in hindbrain areas (e.g. dorsal vagal complex (DVC)) linked to the control of meal size and forebrain areas (e.g. hypothalamus, amygdala) linked to the regulation of food intake and body weight. This review assesses the potential central and peripheral targets by which oxytocin may inhibit body weight gain, its regulation by anorexigenic and orexigenic signals, and its potential use as a therapy that can circumvent leptin resistance and reverse the behavioral and metabolic abnormalities associated with DIO and genetically obese models.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. [Comparative Study]. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491–7. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.39.

den Hertog CE, de Groot AN, van Dongen PW. History and use of oxytocics. [Historical Article Review]. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;94(1):8–12.

Braude R, Mitchell KG. Observations on the relationship between oxytocin and adrenaline in milk ejection in the sow. J Endocrinol. 1952;8(3):238–41.

Verbalis JG, Blackburn RE, Hoffman GE, Stricker EM. Establishing behavioral and physiological functions of central oxytocin: insights from studies of oxytocin and ingestive behaviors. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. Review]. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;395:209–25.

Striepens N, Kendrick KM, Maier W, Hurlemann R. Prosocial effects of oxytocin and clinical evidence for its therapeutic potential. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2011;32(4):426–50. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2011.07.001.

Yamasue H, Yee JR, Hurlemann R, Rilling JK, Chen FS, Meyer-Lindenberg A, et al. Integrative approaches utilizing oxytocin to enhance prosocial behavior: from animal and human social behavior to autistic social dysfunction. [Review]. J Neurosci. 2012;32(41):14109–17. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3327-12.2012.

Montag C, Brockmann EM, Bayerl M, Rujescu D, Muller DJ, Gallinat J. Oxytocin and oxytocin receptor gene polymorphisms and risk for schizophrenia: A case–control study. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012. doi:10.3109/15622975.2012.677547.

Deblon N, Veyrat-Durebex C, Bourgoin L, Caillon A, Bussier AL, Petrosino S, et al. Mechanisms of the anti-obesity effects of oxytocin in diet-induced obese rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25565. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025565.

Kublaoui BM, Gemelli T, Tolson KP, Wang Y, Zinn AR. Oxytocin deficiency mediates hyperphagic obesity of Sim1 haploinsufficient mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22(7):1723–34. doi:10.1210/me.2008-0067.

Maejima Y, Iwasaki Y, Yamahara Y, Kodaira M, Sedbazar U, Yada T. Peripheral oxytocin treatment ameliorates obesity by reducing food intake and visceral fat mass. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Aging (Albany NY). 2011;3(12):1169–77.

Maejima Y, Sedbazar U, Suyama S, Kohno D, Onaka T, Takano E, et al. Nesfatin-1-regulated oxytocinergic signaling in the paraventricular nucleus causes anorexia through a leptin-independent melanocortin pathway. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Cell Metab. 2009;10(5):355–65. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.002.

Morton GJ, Thatcher BS, Reidelberger RD, Ogimoto K, Wolden-Hanson T, Baskin DG, et al. Peripheral oxytocin suppresses food intake and causes weight loss in diet-induced obese rats. [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302(1):E134–144. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00296.2011.

Zhang G, Bai H, Zhang H, Dean C, Wu Q, Li J, et al. Neuropeptide exocytosis involving synaptotagmin-4 and oxytocin in hypothalamic programming of body weight and energy balance. [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neuron. 2011;69(3):523–35. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.036.

Zhang G, Cai D. Circadian intervention of obesity development via resting-stage feeding manipulation or oxytocin treatment. [Evaluation Studies Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301(5):E1004–1012. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00196.2011.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal, KM (2012) Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief.

Jankowski M, Hajjar F, Kawas SA, Mukaddam-Daher S, Hoffman G, McCann SM, et al. Rat heart: a site of oxytocin production and action. [In Vitro Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(24):14558–63.

Rosen GJ, de Vries GJ, Goldman SL, Goldman BD, Forger NG. Distribution of oxytocin in the brain of a eusocial rodent. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Neuroscience. 2008;155(3):809–17. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.039.

Yamashita M, Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Nishimori K, Kusama M, Onaka T. Involvement of prolactin releasing peptide in activation of oxytocin neurones in response to food intake. J Neuroendocrinol. 2013. doi:10.1111/jne.12019.

Shahrokh DK, Zhang TY, Diorio J, Gratton A, Meaney MJ. Oxytocin-dopamine interactions mediate variations in maternal behavior in the rat. Endocrinology. 2010;151(5):2276–86. doi:10.1210/en.2009-1271.

Rinaman L. Oxytocinergic inputs to the nucleus of the solitary tract and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus in neonatal rats. J Comp Neurol. 1998;399(1):101–9.

Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. Immunohistochemical identification of neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus that project to the medulla or to the spinal cord in the rat. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Comp Neurol. 1982;205(3):260–72. doi:10.1002/cne.902050306.

Douglas AJ, Johnstone LE, Leng G. Neuroendocrine mechanisms of change in food intake during pregnancy: a potential role for brain oxytocin. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. Physiol Behav. 2007;91(4):352–65. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.012.

Welch MG, Tamir H, Gross KJ, Chen J, Anwar M, Gershon MD. Expression and developmental regulation of oxytocin (OT) and oxytocin receptors (OTR) in the enteric nervous system (ENS) and intestinal epithelium. J Comp Neurol. 2009;512(2):256–70. doi:10.1002/cne.21872.

Qin J, Feng M, Wang C, Ye Y, Wang PS, Liu C. Oxytocin receptor expressed on the smooth muscle mediates the excitatory effect of oxytocin on gastric motility in rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(4):430–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01282.x.

Ohlsson B, Truedsson M, Djerf P, Sundler F. Oxytocin is expressed throughout the human gastrointestinal tract. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Regul Pept. 2006;135(1–2):7–11. doi:10.1016/j.regpep.2006.03.008.

Wheeler E, Huang N, Bochukova EG, Keogh JM, Lindsay S, Garg S, et al. Genome-wide SNP and CNV analysis identifies common and low-frequency variants associated with severe early-onset obesity. Nat Genet. 2013. doi:10.1038/ng.2607.

Kenny PJ. Common cellular and molecular mechanisms in obesity and drug addiction. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review]. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(11):638–51. doi:10.1038/nrn3105.

Gimpl G, Fahrenholz F. The oxytocin receptor system: structure, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(2):629–83.

Verbalis JG. The brain oxytocin receptor(s)? [Review]. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1999;20(2):146–56. doi:10.1006/frne.1999.0178.

Yoshida M, Takayanagi Y, Inoue K, Kimura T, Young LJ, Onaka T, et al. Evidence that oxytocin exerts anxiolytic effects via oxytocin receptor expressed in serotonergic neurons in mice. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. J Neurosci. 2009;29(7):2259–71. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5593-08.2009.

Gould BR, Zingg HH. Mapping oxytocin receptor gene expression in the mouse brain and mammary gland using an oxytocin receptor-LacZ reporter mouse. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neuroscience. 2003;122(1):155–67.

Schaffler A, Binart N, Scholmerich J, Buchler C. Hypothesis paper Brain talks with fat–evidence for a hypothalamic-pituitary-adipose axis? [Review]. Neuropeptides. 2005;39(4):363–7. doi:10.1016/j.npep.2005.06.003.

Tsuda T, Ueno Y, Yoshikawa T, Kojo H, Osawa T. Microarray profiling of gene expression in human adipocytes in response to anthocyanins. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71(8):1184–97. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.042.

van den Burg EH, Neumann ID. Bridging the gap between GPCR activation and behaviour: oxytocin and prolactin signalling in the hypothalamus. [Review]. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;43(2):200–8. doi:10.1007/s12031-010-9452-8.

Gravati M, Busnelli M, Bulgheroni E, Reversi A, Spaiardi P, Parenti M, et al. Dual modulation of inward rectifier potassium currents in olfactory neuronal cells by promiscuous G protein coupling of the oxytocin receptor. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Neurochem. 2010;114(5):1424–35. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06861.x.

Arletti R, Benelli A, Bertolini A. Influence of oxytocin on feeding behavior in the rat. Peptides. 1989;10(1):89–93.

Arletti R, Benelli A, Bertolini A. Oxytocin inhibits food and fluid intake in rats. Physiol Behav. 1990;48(6):825–30.

Lokrantz CM, Uvnas-Moberg K, Kaplan JM. Effects of central oxytocin administration on intraoral intake of glucose in deprived and nondeprived rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Physiol Behav. 1997;62(2):347–52.

Olson BR, Drutarosky MD, Chow MS, Hruby VJ, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Oxytocin and an oxytocin agonist administered centrally decrease food intake in rats. Peptides. 1991;1991:113–8.

Rinaman L, Rothe EE. GLP-1 receptor signaling contributes to anorexigenic effect of centrally administered oxytocin in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283(1):R99–106.

Blouet C, Jo YH, Li X, Schwartz GJ. Mediobasal hypothalamic leucine sensing regulates food intake through activation of a hypothalamus-brainstem circuit. J Neurosci. 2009;29(26):8302–11. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1668-09.2009.

Johnstone LE, Fong TM, Leng G. Neuronal activation in the hypothalamus and brainstem during feeding in rats. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Cell Metab. 2006;4(4):313–21. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2006.08.003.

Lucio-Oliveira F, Franci CR. Effect of the interaction between food state and the action of estrogen on oxytocinergic system activity. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Endocrinol. 2012;212(2):129–38. doi:10.1530/JOE-11-0272.

Olszewski PK, Klockars A, Olszewska AM, Fredriksson R, Schioth HB, Levine AS. Molecular, immunohistochemical, and pharmacological evidence of oxytocin’s role as inhibitor of carbohydrate but not fat intake. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Endocrinology. 2010;151(10):4736–44. doi:10.1210/en.2010-0151.

Singru PS, Wittmann G, Farkas E, Zseli G, Fekete C, Lechan RM. Refeeding-activated glutamatergic neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) mediate effects of melanocortin signaling in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS). [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Endocrinology. 2012;153(8):3804–14. doi:10.1210/en.2012-1235.

Olson BR, Hoffman GE, Sved AF, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Cholecystokinin induces c-fos expression in hypothalamic oxytocinergic neurons projecting to the dorsal vagal complex. Brain Res. 1992;569(2):238–48.

Renaud LP, Tang M, McCann MJ, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Cholecystokinin and gastric distension activate oxytocinergic cells in rat hypothalamus. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol. 1987;253(4 Pt 2):R661–665.

Nelson EE, Alberts JR, Tian Y, Verbalis JG. Oxytocin is elevated in plasma of 10-day-old rats following gastric distension. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;111(2):301–3.

Zhang J, Liu S, Tang M, Chen JD. Optimal locations and parameters of gastric electrical stimulation in altering ghrelin and oxytocin in the hypothalamus of rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neurosci Res. 2008;62(4):262–9. doi:10.1016/j.neures.2008.09.004.

Tang M, Zhang J, Xu L, Chen JD. Implantable gastric stimulation alters expression of oxytocin- and orexin-containing neurons in the hypothalamus of rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Obes Surg. 2006;16(6):762–9. doi:10.1381/096089206777346745.

Ueta Y, Kannan H, Higuchi T, Negoro H, Yamaguchi K, Yamashita H. Activation of gastric afferents increases noradrenaline release in the paraventricular nucleus and plasma oxytocin level. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Auton Nerv Syst. 2000;78(2–3):69–76.

Gaetani S, Fu J, Cassano T, Dipasquale P, Romano A, Righetti L, et al. The fat-induced satiety factor oleoylethanolamide suppresses feeding through central release of oxytocin. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Neurosci. 2010;30(24):8096–101. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0036-10.2010.

Flak JN, Jankord R, Solomon MB, Krause EG, Herman JP. Opposing effects of chronic stress and weight restriction on cardiovascular, neuroendocrine and metabolic function. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Physiol Behav. 2011;104(2):228–34. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.03.002.

Tung YC, Ma M, Piper S, Coll A, O’Rahilly S, Yeo GS. Novel leptin-regulated genes revealed by transcriptional profiling of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Neurosci. 2008;28(47):12419–26. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3412-08.2008.

Blevins JE, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG. Evidence that paraventricular nucleus oxytocin neurons link hypothalamic leptin action to caudal brain stem nuclei controlling meal size. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287(1):R87–96. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00604.2003.

Takayanagi Y, Kasahara Y, Onaka T, Takahashi N, Kawada T, Nishimori K. Oxytocin receptor-deficient mice developed late-onset obesity. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neuroreport. 2008;19(9):951–5. doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283021ca9.

Dombret C, Nguyen T, Schakman O, Michaud JL, Hardin-Pouzet H, Bertrand MJ, et al. Loss of Maged1 results in obesity, deficits of social interactions, impaired sexual behavior and severe alteration of mature oxytocin production in the hypothalamus. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(21):4703–17. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds310.

Swaab DF, Purba JS, Hofman MA. Alterations in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and its oxytocin neurons (putative satiety cells) in Prader-Willi syndrome: a study of five cases. [Case Reports Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(2):573–9.

Wu Z, Xu Y, Zhu Y, Sutton AK, Zhao R, Lowell BB, et al. An obligate role of oxytocin neurons in diet induced energy expenditure. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45167. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045167.

Wu Q, Howell MP, Palmiter RD. Ablation of neurons expressing agouti-related protein activates fos and gliosis in postsynaptic target regions. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Neurosci. 2008;28(37):9218–26. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2449-08.2008.

Lukas M, Bredewold R, Neumann ID, Veenema AH. Maternal separation interferes with developmental changes in brain vasopressin and oxytocin receptor binding in male rats. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58(1):78–87. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.020.

Rogers RC, Hermann GE. Oxytocin, oxytocin antagonist, TRH, and hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus stimulation effects on gastric motility. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Peptides. 1987;8(3):505–13.

McCann MJ, Rogers RC. Oxytocin excites gastric-related neurones in rat dorsal vagal complex. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Physiol. 1990;428:95–108.

Borg J, Simren M, Ohlsson B. Oxytocin reduces satiety scores without affecting the volume of nutrient intake or gastric emptying rate in healthy subjects. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23(1):56–61. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01599.x. e55.

McCann MJ, Verbalis JG, Stricker EM. LiCl and CCK inhibit gastric emptying and feeding and stimulate OT secretion in rats. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol. 1989;256(2 Pt 2):R463–468.

Li L, Kong X, Liu H, Liu C. Systemic oxytocin and vasopressin excite gastrointestinal motility through oxytocin receptor in rabbits. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(10):839–44. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00953.x.

Wu CL, Doong ML, Wang PS. Involvement of cholecystokinin receptor in the inhibition of gastrointestinal motility by oxytocin in ovariectomized rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;580(3):407–15. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.024.

Wu CL, Hung CR, Chang FY, Pau KY, Wang PS. Pharmacological effects of oxytocin on gastric emptying and intestinal transit of a non-nutritive liquid meal in female rats. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2003;367(4):406–13. doi:10.1007/s00210-003-0690-y.

Amico JA, Vollmer RR, Cai HM, Miedlar JA, Rinaman L. Enhanced initial and sustained intake of sucrose solution in mice with an oxytocin gene deletion. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289(6):R1798–1806. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00558.2005.

Sclafani A, Rinaman L, Vollmer RR, Amico JA. Oxytocin knockout mice demonstrate enhanced intake of sweet and nonsweet carbohydrate solutions. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292(5):R1828–1833. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00826.2006.

Mullis K, Kay K, Williams DL. Oxytocin action in the ventral tegmental area affects sucrose intake. Brain Res. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2013.03.026.

Boccia ML, Goursaud AP, Bachevalier J, Anderson KD, Pedersen CA. Peripherally administered non-peptide oxytocin antagonist, L368,899, accumulates in limbic brain areas: a new pharmacological tool for the study of social motivation in non-human primates. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Horm Behav. 2007;52(3):344–51. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.05.009.

Olszewski PK, Levine AS. Central opioids and consumption of sweet tastants: when reward outweighs homeostasis. [Review]. Physiol Behav. 2007;91(5):506–12. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.01.011.

Mitra A, Gosnell BA, Schioth HB, Grace MK, Klockars A, Olszewski PK, et al. Chronic sugar intake dampens feeding-related activity of neurons synthesizing a satiety mediator, oxytocin. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Peptides. 2010;31(7):1346–52. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2010.04.005.

Leng G, Brown CH, Murphy NP, Onaka T, Russell JA. Opioid-noradrenergic interactions in the control of oxytocin cells. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;395:95–104.

Carson DS, Cornish JL, Guastella AJ, Hunt GE, McGregor IS. Oxytocin decreases methamphetamine self-administration, methamphetamine hyperactivity, and relapse to methamphetamine-seeking behaviour in rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58(1):38–43. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.018.

Carson DS, Hunt GE, Guastella AJ, Barber L, Cornish JL, Arnold JC, et al. Systemically administered oxytocin decreases methamphetamine activation of the subthalamic nucleus and accumbens core and stimulates oxytocinergic neurons in the hypothalamus. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Addict Biol. 2010;15(4):448–63. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00247.x.

Qi J, Yang JY, Song M, Li Y, Wang F, Wu CF. Inhibition by oxytocin of methamphetamine-induced hyperactivity related to dopamine turnover in the mesolimbic region in mice. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008;376(6):441–8. doi:10.1007/s00210-007-0245-8.

Covasa M, Ritter RC. Rats maintained on high-fat diets exhibit reduced satiety in response to CCK and bombesin. Peptides. 1998;19(8):1407–15.

Covasa M, Grahn J, Ritter RC. High fat maintenance diet attenuates hindbrain neuronal response to CCK. Regul Pept. 2000;86(1–3):83–8.

Hisadome K, Reimann F, Gribble FM, Trapp S. CCK stimulation of GLP-1 neurons involves alpha1-adrenoceptor-mediated increase in glutamatergic synaptic inputs. [In Vitro Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Diabetes. 2011;60(11):2701–9. doi:10.2337/db11-0489.

Appleyard SM, Marks D, Kobayashi K, Okano H, Low MJ, Andresen MC. Visceral afferents directly activate catecholamine neurons in the solitary tract nucleus. [In Vitro Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. J Neurosci. 2007;27(48):13292–302. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3502-07.2007.

Rinaman L. Hindbrain noradrenergic lesions attenuate anorexia and alter central cFos expression in rats after gastric viscerosensory stimulation. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Neurosci. 2003;23(31):10084–92.

Bechtold DA, Luckman SM. Prolactin-releasing Peptide mediates cholecystokinin-induced satiety in mice. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Endocrinology. 2006;147(10):4723–9. doi:10.1210/en.2006-0753.

Maniscalco JW, Kreisler AD, Rinaman L. Satiation and stress-induced hypophagia: examining the role of hindbrain neurons expressing prolactin-releasing Peptide or glucagon-like Peptide 1. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:199. doi:10.3389/fnins.2012.00199.

Appleyard SM, Bailey TW, Doyle MW, Jin YH, Smart JL, Low MJ, et al. Proopiomelanocortin neurons in nucleus tractus solitarius are activated by visceral afferents: regulation by cholecystokinin and opioids. [Comparative Study In Vitro Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Neurosci. 2005;25(14):3578–85. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4177-04.2005.

Fan W, Ellacott KL, Halatchev IG, Takahashi K, Yu P, Cone RD. Cholecystokinin-mediated suppression of feeding involves the brainstem melanocortin system. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(4):335–6. doi:10.1038/nn1214.

Baskin DG, Kim F, Gelling RW, Russell BJ, Schwartz MW, Morton GJ, et al. A new oxytocin-saporin cytotoxin for lesioning oxytocin-receptive neurons in the rat hindbrain. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Endocrinology. 2010;151(9):4207–13. doi:10.1210/en.2010-0295.

Blevins JE, Eakin TJ, Murphy JA, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG. Oxytocin innervation of caudal brainstem nuclei activated by cholecystokinin. Brain Res. 2003;993(1–2):30–41.

Matarazzo V, Schaller F, Nedelec E, Benani A, Penicaud L, Muscatelli F, et al. Inactivation of Socs3 in the hypothalamus enhances the hindbrain response to endogenous satiety signals via oxytocin signaling. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Neurosci. 2012;32(48):17097–107. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1669-12.2012.

Olson BR, Drutarosky MD, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Brain oxytocin receptor antagonism blunts the effects of anorexigenic treatments in rats: evidence for central oxytocin inhibition of food intake. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Endocrinology. 1991;129(2):785–91.

Alhadeff AL, Rupprecht LE, Hayes MR. GLP-1 neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract project directly to the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens to control for food intake. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Endocrinology. 2012;153(2):647–58. doi:10.1210/en.2011-1443.

Mejias-Aponte CA, Drouin C, Aston-Jones G. Adrenergic and noradrenergic innervation of the midbrain ventral tegmental area and retrorubral field: prominent inputs from medullary homeostatic centers. [Comparative Study Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Neurosci. 2009;29(11):3613–26. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4632-08.2009.

Dossat AM, Lilly N, Kay K, Williams DL. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptors in nucleus accumbens affect food intake. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. J Neurosci. 2011;31(41):14453–7. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3262-11.2011.

Delfs JM, Zhu Y, Druhan JP, Aston-Jones GS. Origin of noradrenergic afferents to the shell subregion of the nucleus accumbens: anterograde and retrograde tract-tracing studies in the rat. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Brain Res. 1998;806(2):127–40.

Wang ZJ, Rao ZR, Shi JW. Tyrosine hydroxylase-, neurotensin-, or cholecystokinin-containing neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarii send projection fibers to the nucleus accumbens in the rat. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Brain Res. 1992;578(1–2):347–50.

Hayes MR, Bradley L, Grill HJ. Endogenous hindbrain glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation contributes to the control of food intake by mediating gastric satiation signaling. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Endocrinology. 2009;150(6):2654–9. doi:10.1210/en.2008-1479.

Barrera JG, Jones KR, Herman JP, D’Alessio DA, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. Hyperphagia and increased fat accumulation in two models of chronic CNS glucagon-like peptide-1 loss of function. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. J Neurosci. 2011;31(10):3904–13. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2212-10.2011.

Zhang Y, Rodrigues E, Gao YX, King M, Cheng KY, Erdos B, et al. Pro-opiomelanocortin gene transfer to the nucleus of the solitary track but not arcuate nucleus ameliorates chronic diet-induced obesity. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Neuroscience. 2010;169(4):1662–71. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.06.001.

Li G, Zhang Y, Rodrigues E, Zheng D, Matheny M, Cheng KY, et al. Melanocortin activation of nucleus of the solitary tract avoids anorectic tachyphylaxis and induces prolonged weight loss. [Evaluation Studies Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293(1):E252–258. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00451.2006.

Baird JP, Palacios M, LaRiviere M, Grigg LA, Lim C, Matute E, et al. Anatomical dissociation of melanocortin receptor agonist effects on taste- and gut-sensitive feeding processes. [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301(4):R1044–1056. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00577.2010.

Covasa M, Ritter RC. Reduced sensitivity to the satiation effect of intestinal oleate in rats adapted to high-fat diet. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(1 Pt 2):R279–285.

Donovan MJ, Paulino G, Raybould HE. Activation of hindbrain neurons in response to gastrointestinal lipid is attenuated by high fat, high energy diets in mice prone to diet-induced obesity. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Brain Res. 2009;1248:136–40. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.042.

Olson VG, Heusner CL, Bland RJ, During MJ, Weinshenker D, Palmiter RD. Role of noradrenergic signaling by the nucleus tractus solitarius in mediating opiate reward. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Science. 2006;311(5763):1017–20. doi:10.1126/science.1119311.

Camerino C. Low sympathetic tone and obese phenotype in oxytocin-deficient mice. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(5):980–4. doi:10.1038/oby.2009.12.

Holder Jr JL, Butte NF, Zinn AR. Profound obesity associated with a balanced translocation that disrupts the SIM1 gene. [Case Reports Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(1):101–8.

Swarbrick MM, Evans DS, Valle MI, Favre H, Wu SH, Njajou OT, et al. Replication and extension of association between common genetic variants in SIM1 and human adiposity. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, N.I.H., Intramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19(12):2394–403. doi:10.1038/oby.2011.79.

Backman SB, Henry JL. Effects of oxytocin and vasopressin on thoracic sympathetic preganglionic neurones in the cat. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Brain Res Bull. 1984;13(5):679–84.

Armour JA, Klassen GA. Oxytocin modulation of intrathoracic sympathetic ganglionic neurons regulating the canine heart. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Peptides. 1990;11(3):533–7.

Oldfield BJ, Giles ME, Watson A, Anderson C, Colvill LM, McKinley MJ. The neurochemical characterisation of hypothalamic pathways projecting polysynaptically to brown adipose tissue in the rat. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neuroscience. 2002;110(3):515–26.

Jansen AS, Wessendorf MW, Loewy AD. Transneuronal labeling of CNS neuropeptide and monoamine neurons after pseudorabies virus injections into the stellate ganglion. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Brain Res. 1995;683(1):1–24.

Higa KT, Mori E, Viana FF, Morris M, Michelini LC. Baroreflex control of heart rate by oxytocin in the solitary-vagal complex. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282(2):R537–545. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00806.2000.

Xi D, Gandhi N, Lai M, Kublaoui BM. Ablation of Sim1 neurons causes obesity through hyperphagia and reduced energy expenditure. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36453. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036453.

Lockie SH, Heppner KM, Chaudhary N, Chabenne JR, Morgan DA, Veyrat-Durebex C, et al. Direct control of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis by central nervous system glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Diabetes. 2012;61(11):2753–62. doi:10.2337/db11-1556.

Muchmore DB, Little SA, de Haen C. A dual mechanism of action of ocytocin in rat epididymal fat cells. [Comparative Study In Vitro Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Biol Chem. 1981;256(1):365–72.

Shi H, Bartness TJ. Neurochemical phenotype of sympathetic nervous system outflow from brain to white fat. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Brain Res Bull. 2001;54(4):375–85.

Stanley S, Pinto S, Segal J, Perez CA, Viale A, DeFalco J, et al. Identification of neuronal subpopulations that project from hypothalamus to both liver and adipose tissue polysynaptically. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(15):7024–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1002790107.

Ho JM, Blevins JE. Coming full circle: contributions of central and peripheral oxytocin actions to energy balance. Endocrinology. 2013;154(2):589–96. doi:10.1210/en.2012-1751.

Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte Jr D, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. Review]. Nature. 2000;404(6778):661–71. doi:10.1038/35007534.

Woods SC, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG, Seeley RJ. Food intake and the regulation of body weight. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. Review]. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:255–77. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.255.

Kaplan JM, Seeley RJ, Grill HJ. Daily caloric intake in intact and chronic decerebrate rats. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:876–81.

Shapiro RE, Miselis RR. The central organization of the vagus nerve innervating the stomach of the rat. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Comp Neurol. 1985;238(4):473–88. doi:10.1002/cne.902380411.

Olson BR, Freilino M, Hoffman GE, Stricker EM, Sved AF, Verbalis JG. c-Fos expression in rat brain and brainstem nuclei in response to treatments that alter food intake and gastric motility. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1993;4:93–106.

Edwards GL, Ladenheim EE, Ritter RC. Dorsomedial hindbrain participation in cholecystokinin-induced satiety. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol. 1986;251(5 Pt 2):R971–977.

Fraser KA, Raizada E, Davison JS. Oral-pharyngeal-esophageal and gastric cues contribute to meal-induced c-fos expression. Am J Physiol. 1995;268(1 Pt 2):R223–230.

Willing AE, Berthoud HR. Gastric distension-induced c-fos expression in catecholaminergic neurons of rat dorsal vagal complex. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol. 1997;272(1 Pt 2):R59–67.

Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. The organization of noradrenergic pathways from the brainstem to the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei in the rat. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Brain Res. 1982;257(3):275–325.

Crawley JN, Kiss JZ. Paraventricular nucleus lesions abolish the inhibition of feeding induced by systemic cholecystokinin. Peptides. 1985;6(5):927–35.

Leibowitz SF, Hammer NJ, Chang K. Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus lesions produce overeating and obesity in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1981;27(6):1031–40.

Kirchgessner AL, Sclafani A. PVN-hindbrain pathway involved in the hypothalamic hyperphagia-obesity syndrome. Physiol Behav. 1988;42:517–28.

Qi Y, Henry BA, Oldfield BJ, Clarke IJ. The action of leptin on appetite-regulating cells in the ovine hypothalamus: demonstration of direct action in the absence of the arcuate nucleus. Endocrinology. 2010;151(5):2106–16. doi:10.1210/en.2009-1283.

Perello M, Raingo J. Leptin activates oxytocin neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in both control and diet-induced obese rodents. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59625. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059625.

Munzberg H, Flier JS, Bjorbaek C. Region-specific leptin resistance within the hypothalamus of diet-induced obese mice. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Endocrinology. 2004;145(11):4880–9. doi:10.1210/en.2004-0726.

Baskin DG, Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Woods SC, Porte Jr D, Breininger JF, et al. Leptin receptor long-form splice-variant protein expression in neuron cell bodies of the brain and co-localization with neuropeptide Y mRNA in the arcuate nucleus. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47(3):353–62.

Seeley RJ, Yagaloff KA, Fisher SL, Burn P, Thiele TE, van Dijk G, et al. Melanocortin receptors in leptin effects. [Letter]. Nature. 1997;390(6658):349. doi:10.1038/37016.

Olszewski PK, Wirth MM, Shaw TJ, Grace MK, Billington CJ, Giraudo SQ, et al. Role of alpha-MSH in the regulation of consummatory behavior: immunohistochemical evidence. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281(2):R673–680.

Liu H, Kishi T, Roseberry AG, Cai X, Lee CE, Montez JM, et al. Transgenic mice expressing green fluorescent protein under the control of the melanocortin-4 receptor promoter. [In Vitro Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Neurosci. 2003;23(18):7143–54.

Blevins JE, Morton GJ, Williams DL, Caldwell DW, Bastian LS, Wisse BE, et al. Forebrain melanocortin signaling enhances the hindbrain satiety response to CCK-8. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296(3):R476–484. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.90544.2008.

Yosten GL, Samson WK. The anorexigenic and hypertensive effects of nesfatin-1 are reversed by pretreatment with an oxytocin receptor antagonist. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298(6):R1642–1647. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00804.2009.

Myers Jr MG, Leibel RL, Seeley RJ, Schwartz MW. Obesity and leptin resistance: distinguishing cause from effect. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21(11):643–51. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2010.08.002.

Van Heek M, Compton DS, France CF, Tedesco RP, Fawzi AB, Graziano MP, et al. Diet-induced obese mice develop peripheral, but not central, resistance to leptin. [Clinical Trial]. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(3):385–90. doi:10.1172/JCI119171.

Lin S, Thomas TC, Storlien LH, Huang XF. Development of high fat diet-induced obesity and leptin resistance in C57Bl/6J mice. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(5):639–46.

Banks WA, DiPalma CR, Farrell CL. Impaired transport of leptin across the blood–brain barrier in obesity. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Peptides. 1999;20(11):1341–5.

Knight ZA, Hannan KS, Greenberg ML, Friedman JM. Hyperleptinemia is required for the development of leptin resistance. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11376. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011376.

El-Haschimi K, Pierroz DD, Hileman SM, Bjorbaek C, Flier JS. Two defects contribute to hypothalamic leptin resistance in mice with diet-induced obesity. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(12):1827–32. doi:10.1172/JCI9842.

Milagro FI, Campion J, Garcia-Diaz DF, Goyenechea E, Paternain L, Martinez JA. High fat diet-induced obesity modifies the methylation pattern of leptin promoter in rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Physiol Biochem. 2009;65(1):1–9.

De Souza CT, Araujo EP, Bordin S, Ashimine R, Zollner RL, Boschero AC, et al. Consumption of a fat-rich diet activates a proinflammatory response and induces insulin resistance in the hypothalamus. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Endocrinology. 2005;146(10):4192–9. doi:10.1210/en.2004-1520.

Bence KK, Delibegovic M, Xue B, Gorgun CZ, Hotamisligil GS, Neel BG, et al. Neuronal PTP1B regulates body weight, adiposity and leptin action. [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Nat Med. 2006;12(8):917–24. doi:10.1038/nm1435.

Loh K, Fukushima A, Zhang X, Galic S, Briggs D, Enriori PJ, et al. Elevated hypothalamic TCPTP in obesity contributes to cellular leptin resistance. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Cell Metab. 2011;14(5):684–99. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2011.09.011.

Lee HJ, Caldwell HK, Macbeth AH, Tolu SG, Young 3rd WS. A conditional knockout mouse line of the oxytocin receptor. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, N.I.H., Intramural]. Endocrinology. 2008;149(7):3256–63. doi:10.1210/en.2007-1710.

Hicks C, Jorgensen W, Brown C, Fardell J, Koehbach J, Gruber CW, et al. The nonpeptide oxytocin receptor agonist WAY 267,464: receptor-binding profile, prosocial effects and distribution of c-Fos expression in adolescent rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012;24(7):1012–29. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2012.02311.x.

Mens WB, Witter A, van Wimersma Greidanus TB. Penetration of neurohypophyseal hormones from plasma into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF): half-times of disappearance of these neuropeptides from CSF. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Brain Res. 1983;262(1):143–9.

Kendrick KM, Keverne EB, Baldwin BA, Sharman DF. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of acetylcholinesterase, monoamines and oxytocin during labour, parturition, vaginocervical stimulation, lamb separation and suckling in sheep. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neuroendocrinology. 1986;44(2):149–56.

Neumann ID, Maloumby R, Beiderbeck DI, Lukas M, Landgraf R. Increased brain and plasma oxytocin after nasal and peripheral administration in rats and mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.03.003.

Emch GS, Hermann GE, Rogers RC. TNF-alpha-induced c-Fos generation in the nucleus of the solitary tract is blocked by NBQX and MK-801. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281(5):R1394–1400.

Maolood N, Meister B. Protein components of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) in the brainstem area postrema-nucleus tractus solitarius region. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Chem Neuroanat. 2009;37(3):182–95. doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2008.12.007.

Banks WA. Blood–brain barrier and energy balance. [Review]. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14 Suppl 5:234S–7S. doi:10.1038/oby.2006.315.

Banks WA. The blood–brain barrier as a regulatory interface in the gut-brain axes. [Review]. Physiol Behav. 2006;89(4):472–6. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.07.004.

Ring RH, Malberg JE, Potestio L, Ping J, Boikess S, Luo B, et al. Anxiolytic-like activity of oxytocin in male mice: behavioral and autonomic evidence, therapeutic implications. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;185(2):218–25. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-0293-z.

Vrang N, Larsen PJ, Kristensen P, Tang-Christensen M. Central administration of cocaine-amphetamine-regulated transcript activates hypothalamic neuroendocrine neurons in the rat. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Endocrinology. 2000;141(2):794–801.

Kristensen P, Judge ME, Thim L, Ribel U, Christjansen KN, Wulff BS, et al. Hypothalamic CART is a new anorectic peptide regulated by leptin. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Nature. 1998;393(6680):72–6. doi:10.1038/29993.

Olszewski PK, Fredriksson R, Olszewska AM, Stephansson O, Alsio J, Radomska KJ, et al. Hypothalamic FTO is associated with the regulation of energy intake not feeding reward. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:129. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-10-129.

Olszewski PK, Fredriksson R, Eriksson JD, Mitra A, Radomska KJ, Gosnell BA, et al. Fto colocalizes with a satiety mediator oxytocin in the brain and upregulates oxytocin gene expression. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;408(3):422–6. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.037.

Church C, Moir L, McMurray F, Girard C, Banks GT, Teboul L, et al. Overexpression of Fto leads to increased food intake and results in obesity. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Nat Genet. 2010;42(12):1086–92. doi:10.1038/ng.713.

Fischer J, Koch L, Emmerling C, Vierkotten J, Peters T, Bruning JC, et al. Inactivation of the Fto gene protects from obesity. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Nature. 2009;458(7240):894–8. doi:10.1038/nature07848.

Church C, Lee S, Bagg EA, McTaggart JS, Deacon R, Gerken T, et al. A mouse model for the metabolic effects of the human fat mass and obesity associated FTO gene. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(8):e1000599. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000599.

Blouet C, Schwartz GJ. Brainstem nutrient sensing in the nucleus of the solitary tract inhibits feeding. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Cell Metab. 2012;16(5):579–87. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2012.10.003.

Shimizu H, Oh IS, Okada S, Mori M. Nesfatin-1: an overview and future clinical application. [Review]. Endocr J. 2009;56(4):537–43.

Leone TC, Lehman JJ, Finck BN, Schaeffer PJ, Wende AR, Boudina S, et al. PGC-1alpha deficiency causes multi-system energy metabolic derangements: muscle dysfunction, abnormal weight control and hepatic steatosis. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(4):e101. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030101.

Blechman J, Amir-Zilberstein L, Gutnick A, Ben-Dor S, Levkowitz G. The metabolic regulator PGC-1alpha directly controls the expression of the hypothalamic neuropeptide oxytocin. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Neurosci. 2011;31(42):14835–40. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1798-11.2011.

Atasoy D, Betley JN, Su HH, Sternson SM. Deconstruction of a neural circuit for hunger. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Nature. 2012;488(7410):172–7. doi:10.1038/nature11270.

Smith MJ, Wise PM. Localization of kappa opioid receptors in oxytocin magnocellular neurons in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Brain Res. 2001;898(1):162–5.

Olszewski PK, Shi Q, Billington CJ, Levine AS. Opioids affect acquisition of LiCl-induced conditioned taste aversion: involvement of OT and VP systems. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279(4):R1504–1511.

Brunton PJ, Sabatier N, Leng G, Russell JA. Suppressed oxytocin neuron responses to immune challenge in late pregnant rats: a role for endogenous opioids. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23(5):1241–7. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04614.x.

Douglas AJ, Neumann I, Meeren HK, Leng G, Johnstone LE, Munro G, et al. Central endogenous opioid inhibition of supraoptic oxytocin neurons in pregnant rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Neurosci. 1995;15(7 Pt 1):5049–57.

Kirchgessner AL, Sclafani A, Nilaver G. Histochemical identification of a PVN-hindbrain feeding pathway. Physiol Behav. 1988;42(6):529–43.

Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Kellett DO, Jordan D, Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Andresen MC. Oxytocin enhances cranial visceral afferent synaptic transmission to the solitary tract nucleus. [In Vitro Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Neurosci. 2008;28(45):11731–40. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3419-08.2008.

Sutton GM, Patterson LM, Berthoud HR. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 signaling pathway in solitary nucleus mediates cholecystokinin-induced suppression of food intake in rats. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Neurosci. 2004;24(45):10240–7. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2764-04.2004.

Blevins JE, Chelikani PK, Haver AC, Reidelberger RD. PYY(3–36) induces Fos in the arcuate nucleus and in both catecholaminergic and non-catecholaminergic neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius of rats. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Peptides. 2008;29(1):112–9. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2007.11.003.

Valentine JD, Matta SG, Sharp BM. Nicotine-induced cFos expression in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus is dependent on brainstem effects: correlations with cFos in catecholaminergic and noncatecholaminergic neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Endocrinology. 1996;137(2):622–30.

Faipoux R, Tome D, Gougis S, Darcel N, Fromentin G. Proteins activate satiety-related neuronal pathways in the brainstem and hypothalamus of rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Nutr. 2008;138(6):1172–8.

Rinaman L, Verbalis JG, Stricker EM, Hoffman GE. Distribution and neurochemical phenotypes of caudal medullary neurons activated to express cFos following peripheral administration of cholecystokinin. J Comp Neurol. 1993;338(4):475–90. doi:10.1002/cne.903380402.

Blevins JE, Ho JM, Hwang BJ, Thatcher BS, Anekonda VT, Baskin DG (2012) Fourth ventricular administration of oxytocin activates Fos expression in caudal NTS catecholamine neurons. In: Society for Neuroscience, New Orleans, 2012 (2012 Abstract Viewer and Itinerary Planner. Washington, D.C.: Society for Neuroscience, 2012. Online)

Ho JM, Morton GJ, Baskin DG, Blevins JE (2012) Peripheral oxytocin activates Fos expression in NTS catecholamine neurons. In: Society for Neuroscience, New Orleans, 2012 (2012 Abstract Viewer and Itinerary Planner. Washington, D.C.: Society for Neuroscience. Online)

Rothe E, Rinaman L. Central oxytocin (OT) activates hindbrain glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) neurons in rats. Appetite. 2001;37:160.

Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Kellett DO, Jordan D, Browning KN, Travagli RA. Oxytocin-immunoreactive innervation of identified neurons in the rat dorsal vagal complex. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(3):e136–146. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01851.x.

Williams DL, Schwartz MW, Bastian LS, Blevins JE, Baskin DG. Immunocytochemistry and laser capture microdissection for real-time quantitative PCR identify hindbrain neurons activated by interaction between leptin and cholecystokinin. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56(3):285–93. doi:10.1369/jhc.7A7331.2007.

Babic T, Townsend RL, Patterson LM, Sutton GM, Zheng H, Berthoud HR. Phenotype of neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract that express CCK-induced activation of the ERK signaling pathway. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296(4):R845–854. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.90531.2008.

Garfield AS, Patterson C, Skora S, Gribble FM, Reimann F, Evans ML, et al. Neurochemical characterization of body weight-regulating leptin receptor neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Endocrinology. 2012;153(10):4600–7. doi:10.1210/en.2012-1282.

Davies BT, Wellman PJ. Effects on ingestive behavior in rats of the alpha 1-adrenoceptor agonist cirazoline. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;210(1):11–6.

Wellman PJ. Norepinephrine and the control of food intake. [Review]. Nutrition. 2000;16(10):837–42.

Sands SA, Morilak DA. Expression of alpha1D adrenergic receptor messenger RNA in oxytocin- and corticotropin-releasing hormone-synthesizing neurons in the rat paraventricular nucleus. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Neuroscience. 1999;91(2):639–49.

Maruyama M, Matsumoto H, Fujiwara K, Noguchi J, Kitada C, Fujino M, et al. Prolactin-releasing peptide as a novel stress mediator in the central nervous system. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Endocrinology. 2001;142(5):2032–8.

Lawrence CB, Celsi F, Brennand J, Luckman SM. Alternative role for prolactin-releasing peptide in the regulation of food intake. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(7):645–6. doi:10.1038/76597.

Takayanagi Y, Matsumoto H, Nakata M, Mera T, Fukusumi S, Hinuma S, et al. Endogenous prolactin-releasing peptide regulates food intake in rodents. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(12):4014–24. doi:10.1172/JCI34682.

Bjursell M, Lenneras M, Goransson M, Elmgren A, Bohlooly YM. GPR10 deficiency in mice results in altered energy expenditure and obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363(3):633–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.016.

Gu W, Geddes BJ, Zhang C, Foley KP, Stricker-Krongrad A. The prolactin-releasing peptide receptor (GPR10) regulates body weight homeostasis in mice. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;22(1–2):93–103. doi:10.1385/JMN:22:1-2:93.

Larsen PJ, Tang-Christensen M, Holst JJ, Orskov C. Distribution of glucagon-like peptide-1 and other preproglucagon-derived peptides in the rat hypothalamus and brainstem. Neuroscience. 1997;77(1):257–70.

Rinaman L. Interoceptive stress activates glucagon-like peptide-1 neurons that project to the hypothalamus. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(2 Pt 2):R582–590.

Sawchenko PE, Arias C, Bittencourt JC. Inhibin beta, somatostatin, and enkephalin immunoreactivities coexist in caudal medullary neurons that project to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. J Comp Neurol. 1990;291(2):269–80. doi:10.1002/cne.902910209.

Hisadome K, Reimann F, Gribble FM, Trapp S. Leptin directly depolarizes preproglucagon neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius: electrical properties of glucagon-like Peptide 1 neurons. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Diabetes. 2010;59(8):1890–8. doi:10.2337/db10-0128.

Vrang N, Phifer CB, Corkern MM, Berthoud HR. Gastric distension induces c-Fos in medullary GLP-1/2-containing neurons. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285(2):R470–478. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00732.2002.

Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Reimann F, Gribble FM, Trapp S. Preproglucagon neurons project widely to autonomic control areas in the mouse brain. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neuroscience. 2011;180:111–21. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.023.

McMahon LR, Wellman PJ. PVN infusion of GLP-1-(7–36) amide suppresses feeding but does not induce aversion or alter locomotion in rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(1 Pt 2):R23–29.

Zueco JA, Esquifino AI, Chowen JA, Alvarez E, Castrillon PO, Blazquez E. Coexpression of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor, vasopressin, and oxytocin mRNAs in neurons of the rat hypothalamic supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei: effect of GLP-1(7–36)amide on vasopressin and oxytocin release. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Neurochem. 1999;72(1):10–6.

Larsen PJ, Tang-Christensen M, Jessop DS. Central administration of glucagon-like peptide-1 activates hypothalamic neuroendocrine neurons in the rat. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Endocrinology. 1997;138(10):4445–55.

Kendrick KM (2000) Oxytocin, motherhood and bonding. [Review]. Exp Physiol, 85 Spec No, 111S-124S.

Sandoval DA, Bagnol D, Woods SC, D’Alessio DA, Seeley RJ. Arcuate glucagon-like peptide 1 receptors regulate glucose homeostasis but not food intake. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Diabetes. 2008;57(8):2046–54. doi:10.2337/db07-1824.

Schick RR, Zimmermann JP, vorm Walde T, Schusdziarra V. Peptides that regulate food intake: glucagon-like peptide 1-(7–36) amide acts at lateral and medial hypothalamic sites to suppress feeding in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284(6):R1427–1435.

Scott MM, Williams KW, Rossi J, Lee CE, Elmquist JK. Leptin receptor expression in hindbrain Glp-1 neurons regulates food intake and energy balance in mice. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2413–21. doi:10.1172/JCI43703.

Sutton GM, Duos B, Patterson LM, Berthoud HR. Melanocortinergic modulation of cholecystokinin-induced suppression of feeding through extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in rat solitary nucleus. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Endocrinology. 2005;146(9):3739–47. doi:10.1210/en.2005-0562.

Moos F, Richard P. Paraventricular and supraoptic bursting oxytocin cells in rat are locally regulated by oxytocin and functionally related. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Physiol. 1989);408:1–18.

Yamashita H, Okuya S, Inenaga K, Kasai M, Uesugi S, Kannan H, et al. Oxytocin predominantly excites putative oxytocin neurons in the rat supraoptic nucleus in vitro. [In Vitro Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Brain Res. 1987;416(2):364–8.

Catheline G, Touquet B, Lombard MC, Poulain DA, Theodosis DT. A study of the role of neuro-glial remodeling in the oxytocin system at lactation. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neuroscience. 2006;137(1):309–16. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.042.

Rossoni E, Feng J, Tirozzi B, Brown D, Leng G, Moos F. Emergent synchronous bursting of oxytocin neuronal network. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4(7):e1000123. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000123.

Moos F, Freund-Mercier MJ, Guerne Y, Guerne JM, Stoeckel ME, Richard P. Release of oxytocin and vasopressin by magnocellular nuclei in vitro: specific facilitatory effect of oxytocin on its own release. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Endocrinol. 1984;102(1):63–72.

Vankrieken L, Godart A, Thomas K. Oxytocin determination by radioimmunoassay. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1983;16(3):180–5.

Reidelberger RD, Haver AC, Apenteng BA, Anders KL, Steenson SM. Effects of exendin-4 alone and with peptide YY(3–36) on food intake and body weight in diet-induced obese rats. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19(1):121–7. doi:10.1038/oby.2010.136.

Slattery DA, Neumann ID. Chronic icv oxytocin attenuates the pathological high anxiety state of selectively bred Wistar rats. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58(1):56–61. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.038.

Petersson M, Uvnas-Moberg K. Postnatal oxytocin treatment of spontaneously hypertensive male rats decreases blood pressure and body weight in adulthood. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neurosci Lett. 2008;440(2):166–9. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.091.

Ondrejcakova M, Barancik M, Bartekova M, Ravingerova T, Jezova D. Prolonged oxytocin treatment in rats affects intracellular signaling and induces myocardial protection against infarction. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2012;31(3):261–70. doi:10.4149/gpb_2012_030.

Verbalis JG, McHale CM, Gardiner TW, Stricker EM. Oxytocin and vasopressin secretion in response to stimuli producing learned taste aversions in rats. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Behav Neurosci. 1986;100(4):466–75.

Chang SW, Barter JW, Ebitz RB, Watson KK, Platt ML. Inhaled oxytocin amplifies both vicarious reinforcement and self reinforcement in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(3):959–64. doi:10.1073/pnas.1114621109.

Gossen A, Hahn A, Westphal L, Prinz S, Schultz RT, Grunder G, et al. Oxytocin plasma concentrations after single intranasal oxytocin administration - a study in healthy men. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Neuropeptides. 2012;46(5):211–5. doi:10.1016/j.npep.2012.07.001.

MacDonald E, Dadds MR, Brennan JL, Williams K, Levy F, Cauchi AJ. A review of safety, side-effects and subjective reactions to intranasal oxytocin in human research. [Evaluation Studies Review]. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(8):1114–26. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.02.015.

Born J, Lange T, Kern W, McGregor GP, Bickel U, Fehm HL. Sniffing neuropeptides: a transnasal approach to the human brain. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(6):514–6. doi:10.1038/nn849.

Dhuria SV, Hanson LR, Frey 2nd WH. Novel vasoconstrictor formulation to enhance intranasal targeting of neuropeptide therapeutics to the central nervous system. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328(1):312–20. doi:10.1124/jpet.108.145565.

Goldman MB, Gomes AM, Carter CS, Lee R. Divergent effects of two different doses of intranasal oxytocin on facial affect discrimination in schizophrenic patients with and without polydipsia. [Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;216(1):101–10. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2193-8.

Rubin LH, Carter CS, Drogos L, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Sweeney JA, Maki PM. Peripheral oxytocin is associated with reduced symptom severity in schizophrenia. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Schizophr Res. 2010;124(1–3):13–21. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2010.09.014.

Alvares GA, Hickie IB, Guastella AJ. Acute effects of intranasal oxytocin on subjective and behavioral responses to social rejection. [Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;18(4):316–21. doi:10.1037/a0019719.

Devost D, Zingg HH. Homo- and hetero-dimeric complex formations of the human oxytocin receptor. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16(4):372–7. doi:10.1111/j.0953-8194.2004.01188.x.

Viero C, Shibuya I, Kitamura N, Verkhratsky A, Fujihara H, Katoh A, et al. REVIEW: Oxytocin: Crossing the bridge between basic science and pharmacotherapy. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review]. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(5):e138–156. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00185.x.

Bales KL, Perkeybile AM, Conley OG, Lee MH, Guoynes CD, Downing GM, et al. Chronic Intranasal Oxytocin Causes Long-Term Impairments in Partner Preference Formation in Male Prairie Voles. Biol Psychiatry. 2012. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.025.

Miller G. Neuroscience. The promise and perils of oxytocin. [News]. Science. 2013;339(6117):267–9. doi:10.1126/science.339.6117.267.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The research in our laboratory has been supported by the Department of VA Merit Review Research Program. The authors are appreciative of the efforts by Vishwanath Anekonda, Benjamin Thompson, Denis Baskin and Bang Hwang for their assistance in critically reviewing this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

James Blevins and Jacqueline Ho have no conflicts of interest in the data presented in this review.