Abstract

We present evidence on the effect of a public health crisis on housing markets through the lens of the recent opioid crisis in the U.S. Using data on opioid prescriptions and repeat sales in Ohio, we find that house price changes around opioid dispensaries are negatively associated with the quantity of opioids dispensed. To explore a causal inference, we use a potentially cleaner measure of supply that is based on vertical integration. We estimate that a one standard deviation increase in the standardized number of pills dispensed by vertically integrated pharmacies is associated with a 5.8% decrease in house price appreciation. Our work informs the broader policy discussion on economic costs resulting from health crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

We study the effect of a public health epidemic on the housing market through the lens of the recent opioid crisis in the U.S. Specifically, whether the opioid crisis, which refers to the overuse and misuse of prescription opioids, affects house prices. The rise in usage of prescription opioids from the late 1990s culminated in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declaring a public health emergency. In this study, we conjecture that house price changes around opioid dispensaries are negatively associated with the quantity of opioids dispensed and present related empirical evidence.

We use a novel dataset of opioid prescriptions in Ohio. Detailed prescription data is typically not available to the public; however, an order from a lawsuit filed by the Washington Post in a federal court in Ohio resulted in a limited release of prescription opioid data. We exploit spatial and temporal variations in micro-level opioid prescription data to identify its relation with house prices. Our main empirical results comprises of a repeat sales framework to account for static characteristics that are fixed over time. We consider different standardized measures for opioid dispense and use near to a property, i.e. within 2-miles of a property. The first two standardized measures are based on the dispense within 2-miles of a repeat sale property, i.e. number of pills per pharmacy and the number of pills per property. We find a significant, negative association between the number of pills dispensed and the returns for nearby properties. However, the results based on these measures limit causal inferences. Hence, we consider variation in opioid dispensary type to develop a cleaner measure of supply. Pharmacies that receive almost all of their opioids (for subsequent dispense) from their parent company that also serve as a distributor have a vertically integrated supply chain. Distributors have a responsibility to report suspicious orders. However, vertical integration may skew monitoring incentives. Our next two standardized measures are based on the dispense by distributor-pharmacies. We show that our results persist for dispense measures based only on such distributor-pharmacies that may involve ease of flow in the supply chain. The results based on dispense measures by vertically integrated pharmacies may potentially imply a causal narrative on supply side factors having a negative effect on house prices. A one standard deviation increase in the standardized number of pills by distributor-pharmacies is associated with a 5.8% decrease in house price appreciation.

We highlight the robustness of our results through additional tests. First, we account for dispensary openings and closings. Second, we examine a subset of transactions in higher dispense opioid areas to mitigate an alternate explanation that differences between “opioid areas” and non-opioid areas may be driving the results. Third, we account for outliers in terms of opioid dispense. Fourth, we address concerns that our results may be driven by factors related to the financial crisis since our study period overlaps the Great Recession. Our overall inference remains unchanged through either robustness check.

Furthermore, we assuage concerns that vertically integrated pharmacies may endogenously locate in areas with a higher demand for opioids. We identify a relatively more homogeneous subset of transactions in terms of the location choice, i.e. involving dispense by vertically integrated pharmacies and re-do the analysis. In addition, we account for the concern that vertically integrated pharmacies may endogenously locate in areas with a higher demand for opioids in another way by controlling for a measure of demand for opioids in the area, i.e. dispense by dispensaries that are not vertically integrated. Either way, our overall inference remains unchanged.

Our work lies at the intersection of several lines of inquiry. We contribute to the growing literature that studies public health factors and its effect on housing markets. For instance, Tyndall (2019) exploits variation generated by the opening and closing dates of marijuana dispensaries in Vancouver, Canada and studies externalities in the housing market. The author infers that such dispensaries impose a negative price effect on nearby homes. Wong (2008) investigates the effect of the 2003 Hong Kong Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic on housing markets and finds that prices declined by 1%-3% for affected housing complexes. More recently, Francke and Korevaar (2020) study the effect of pandemics on housing markets by examining the outbreak of plague in 17th-century Amsterdam and cholera in 19th-century Paris. The authors find a short-term, negative price effect on housing markets. The recent Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic too is sparking interest. Ling et al. (2020) document a negative relation between COVID-19 exposure and commercial real estate prices. D’Lima et al. (2020) examine the effect of COVID-19 shutdown orders on the housing market and find heterogeneous pricing effects. In line with these studies, our goal is to identify the implicit price discount related to opioid usage and the negative symptoms of drug abuse. We consider opioid dispensing locations as a locus of supply for neighborhoods, and test for a relation between opioid dispense and house prices.

Closest to our work is a study by Custodio et al. (2021). The authors study the relation between opioid abuse and real estate prices by examining the passage of state laws that are intended to limit opioid abuse. We contribute to the literature by highlighting the relation between opioid dispense and real estate prices through micro-level evidence and by examining dispense measures by vertically integrated pharmacies that may potentially imply a causal narrative on supply side factors having a negative effect on house prices. In addition, we inform the broader policy discussion on expending resources to mitigate health crises by quantifying costs that arise beyond direct health related effects. The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. The next section presents an overview of the opioid crisis and develops the hypothesis, followed by a description of the data in Section 3. Section 4 presents the empirical methodology and results. Finally, we conclude with a discussion on the implications of our findings in Section 5.

Background & Hypotheses Development

The rapid expansion in the prescription and consumption of opioids may be attributed to supply-side factors. For instance, the manufacturing and marketing of opioids as well as shifting attitudes of physicians have attracted the most discussion. Starting in the 1990s, pain was declared the “5th vital sign” by the American Pain Society. Purdue Pharma introduced OxyContin in 1996, which was marketed aggressively and went from $48 million in revenue to $1.1 billion in 2000 (Evans et al. (2019)). The result, over this period, was rapid surges in the prescribed population, the number of prescriptions per person, and the dosage size of each prescription. Kenan et al. (2012) note a 35.2% increase in opioid prescriptions per 100 persons and a 69.7% increase in dosage size between 2000 and 2010 across the U.S. This increase in the supply and usage of prescription opioids is positively associated with increased dependence and addiction. For example, Edlund et al. (2014) find that patients with a chronic non-cancer pain condition who were prescribed opioids had significantly higher rates of opioid use disorders than those who were not prescribed opioids.

There are several adverse health, social and economic outcomes from opioid misuse that provide a basis for hypothesizing an effect on house prices. There may be first-order effects such as illegal drug use and criminal activity that may arise from opioid misuse.Footnote 1 Such first-order effects are a dis-amenity that will dampen property price appreciation. In addition, there may be second-order effects due to broader implications for the local economy. For example, Case and Deaton (2020) characterize opioids deaths as a “death of despair” and note that opioid addictions have an impact on individuals’ social and labor market outcomes. In general, economic activity is depressed in areas near to the focal point of drug usage.Footnote 2 The cumulative impact of the first-and second-order effects will result in a decrease in demand and buyers potentially bidding lower prices. Thus, we conjecture that demand side effects on the real estate market resulting from opioid dispense may result in observing a negative association between opioid dispense and house price appreciation.

On the other hand there may be supply side effects. Opioid addiction among homeowners may result in outcomes such as death or financial instability that affects the ability to make mortgage payments. For instance, Elul et al. (2010) find that borrower illiquidity is associated with mortgage default. Such outcomes could result in an increase in supply as properties are listed for sale. The resultant increase in supply of properties on the market may result in lower bid prices. Hence, we conjecture that such supply side effects resulting from opioid dispense may result in observing a negative association between opioid dispense and house price appreciation.

Lastly, to assume a local real estate market effect around opioid dispensaries, the use and abuse of opioids need to be local. We rely on prior work by Cepeda et al. (2013) who find very little opioid shopping or traveling to obtain and fill opioid prescriptions by tracking the distance subjects travel between the pharmacies where their opioid prescriptions are filled. With data on over 10 million subjects in the United States with at least three opioid prescriptions in 2008 and followed for 18 months, Cepeda et al. (2013) classifies shoppers as those that fill overlapping prescriptions, have more than one prescriber and go to more than two pharmacies. Nearly all (99.3%) of over 10 million subjects were classified as non-shoppers, shopping at only one pharmacy. The study finds that the median distance traveled by non-shoppers was approximately 0 miles. Hence, we conjecture that opioid dispense may be negatively associated with local house price appreciation.

Data

Our analysis is based on data of opioid supply, housing transactions, mapping the distance of one to the other, and assuming proximity matters. This section presents an overview of the opioid and property transaction data.

Opioid Prescription Data

The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 mandates reporting transactions of certain controlled substances to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). A record of each transaction includes the name of the drug, the quantity, the active ingredient (such as Hydrocodone bitartrate hemipentahydrate), and receiver details (“opioid dispensary”, i.e., a pharmacy or practitioner that receives the drugs and then presumably dispenses). This information is stored in the Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS) so the DEA can monitor the distribution and sale of highly addictive drugs. While summary data from ARCOS is available, micro-level transaction data is restricted.

In 2019, a federal judge in Ohio working on a case filed by the Washington Post and HD Media ordered the DEA to release a limited set of opioid transaction information. Since the ruling, the Washington Post secured and made the ARCOS data accessible to the public.Footnote 3 The data provided by the Washington Post gives the time-series of pills of Oxycodone and Hydrocodone received by pharmacies and practitioners.Footnote 4 These two opioids are the most commonly prescribed and represent over 75% of the opioid-market during this time-period. To get a perspective on the potential effects of Oxycodone and Hydrocodone, a comparison with a commonly known pain relieving drug can be drawn. Typically, in medical parlance, analgesic strength of painkillers is measured as a comparison to morphine. Oxycodone is considered 1.5 times as strong as morphine. Hydrocodone is equal in strength to morphine. In contrast, a single dose of Tylenol/aspirin is about 360 times weaker than a dose of morphine.Footnote 5

Our study uses data for Ohio from 2006 to 2012, which is a state that was the focus of the lawsuit and has been hit particularly hard by the opioid crisis.Footnote 6 In Table 1, we compare the economic activity in health care and social assistance for Ohio and non-Ohio states by examining industry-level employment and payroll statistics. The data is obtained from County Business Patterns (CBP) and is categorized by the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). Panel A summarizes the number of employees, establishments, and payroll amount categorized by the 2-digit NAICS code of 62, specifically, for healthcare and social assistance between Ohio and non-Ohio states for 2006 and 2012. By the numbers, Ohio is larger than the average state. Panel B displays the economic activity in healthcare proportionally to state NAICS totals, and depicts that as a percentage health related employment, establishments, and payroll is comparable with non-Ohio states in 2006 and 2012.

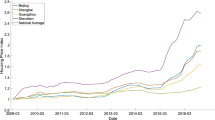

Table 2 reports the average percentage change in median house prices (based on Zillow data) for the top and bottom Ohio zip-codes by the total number of pills dispensed over the study period of 2006 to 2012. Panel A shows the average house price changes from the earliest period available from Zillow (April 1994) through December 2005 for the top-10% and top-20% of zip codes with the most total pills compared to the bottom-10% and bottom-20%, respectively. In the pre-study period there is no discernible difference in median house price appreciation rates between the top and bottom groups. Panel B shows the average house price changes from January 2006 through December 2012. Between the top and bottom-10% there is an absolute difference of 9.8%, which is marginally lower at 7.6% between the top and bottom-20% of zip codes. The evidence suggest parallel trends in prices up to the start of the study period in 2006 that involves the rise of prescription opioids.

Property-Level Data

We obtain property-level data from Zillow, which collects transaction level information from county tax assessor and recorders’ offices. We use property transaction data, such as sales dates and prices, as well as the transacted property’s address and geographic coordinates. Our sample comprises of properties that transact more than once between 2006 and 2012, i.e. 71,009 repeat sales observations.Footnote 7

Summary Statistics

Table 3 presents the summary statistics of the data. Our sample comprises of residential properties and land transactions. The mean number of bedrooms is around 3. Properties are held for an average of 1.9 years and there is substantial variation in the holding period length as indicated by the 1st and 99th percentiles. The mean purchase price is $97,583, and the mean sale price is $109,391.

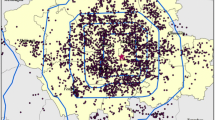

In addition to detailed information on pill shipments to dispensaries, the Washington Post data also includes the exact physical addresses. We geocode the dispense addresses and generate variables that measure the dispense of opioid drugs and map that supply to nearby properties. Since the density of opioid dispensaries varies, we generate two variables to proxy for the number of potential consumers in proximity to a repeat sales property. First, we compute the number of pharmacies within 2-miles of each repeat sales property. Note that pharmacies may be retail or chain. The mean number of pharmacies within 2-miles of each property is 7, and the standard deviation is 6. Second, we compute the number of properties within 2-miles of each repeat sales property. The mean number of properties near a repeat sales property is 10,260. There is considerable variation in the density of properties, as seen in the 1st and 99th percentiles (281 and 31,907 properties, respectively). Thus, the properties span rural and urban areas.

We also present the summary statistics for the number of pills standardized by the number of pharmacies and properties. To enable interpretation, we consider the means for the variables scaled by the length of the holding period. The mean annual number of pills per nearby pharmacy is around 141,500, and the mean annual number of pills per nearby property is 100.

Empirical Results

Repeat Sales Methodology

We use a repeat sales method to test for the relation between opioids dispensed and house price growth. The repeat sales method, first proposed by Bailey et al. (1963) and developed by Case and Shiller (1989) among others, is a common approach in the literature to control for time-invariant heterogeneity in housing markets. Consider transacted properties with purchase prices (\(PP_{it\_}\)) and sales prices (\(SP_{it}\)) that are a function of characteristics (X) and implicit prices (\(\beta\)). If we assume that characteristics are unchanged over transaction pairs with constant implicit prices, then the log of the price ratio, which differences out X and \(\beta\), identifies the quality-adjusted change in house prices. In our base specification, the log return of transaction-pairs, defined as the log sales price over purchase price, \(log(SP_{it}/PP_{it\_})\) is regressed on different measures of opioids dispensed.

Baseline Results

The repeat sales method helps circumvent the addition of a long list of controls that do not change between the purchase and sale dates. We use the following specification:

Here, \(PP_{it\_}\) is the purchase price, and \(SP_{it}\) is the sale price in the repeat sale. \(\# Opioids_{it\_t}\) is one of the following: 1. number of pills divided by the number of nearby pharmacies, or 2. number of pills divided by the number of nearby properties. Both measures are based on a 2-mile radius from a repeat sales property and measure the number of pills for dispense received by dispensaries between the purchase and sale dates.

Table 4 presents the estimated repeat sales regression results based on the two separate explanatory variables of interest.Footnote 8 We include a three-way interaction for purchase-year-quarter, sale-year-quarter, and the county code fixed effects to account for area-specific trends. The three-way interaction specification accounts for general house price changes over time and heterogeneous areas. Columns 1 and 2 present the regression results involving the number of pills per pharmacy and the number of pills per property as explanatory variables respectively. The coefficient of \(\#Pills/\#Pharmacies\) in Column 1 is -0.0018 and statistically significant at the 1% level. This implies a 6.9% decline in house price growth relating to a one standard deviation increase in the standardized measure of pills dispensed, i.e. \(\#Pills/\#Pharmacies\).Footnote 9 The coefficient of \(\#Pills/\#Properties\) in Column 2 is -0.1073 and statistically significant at the 1% level. This implies a 3.4% decline relating to a one standard deviation increase in the \(\#Pills/\#Properties\). Thus, the relation between house price appreciation and opioid dispense appears to be economically meaningful.

We also use variation in the ease of distribution across areas as a cleaner measure of supply to potentially present a causal narrative. Typically, opioid dispensaries receive drugs from distributors. Some pharmacies were in a unique position as it was its own distributor, and its internal distribution centers handled almost all of the pills. The Washington Post notes that “about 2,400 cities and counties nationwide allege that Walgreens failed to report signs of diversion and incentivized pharmacists with bonuses to fill more prescriptions of highly addictive opioids.” Further details are noted in Washington Post (2019a). We classify Walgreens’ pharmacies as distributor-pharmacies. Distributors have a responsibility to report suspicious orders made by dispensaries. Monitoring incentives may be mis-aligned when distributors and pharmacies are vertically integrated, and one may conjecture a reduction in frictions in the supply chain. We generate a measure of opioids dispensed only through such distributor-pharmacies and re-do the analyses. Columns 3 and 4 present the regression results with \(\#Pills/\#Pharmacies\) and \(\#Pills/\#Properties\) as explanatory variables and these measures are based on the dispense only by pharmacies that have a vertically integrated supply chain. We see that the coefficient of both the standardized measures of pills dispensed is negative and statistically significant. This implies a 5.8% and 4.4% decline in house price growth relating to a one standard deviation increase in the standardized measure of pills dispensed, i.e. \(\#Pills/\#Pharmacies\) and \(\#Pills/\#Properties\) measuring the standardized number of pills dispensed by distributor-pharmacies. Thus, our results persist for measures based on pharmacies that may have less frictions to supply opioids. While the results based on the dispense by all the dispensaries depict an association, the results based on dispense measures by vertically integrated pharmacies are suggestive of a causal narrative on supply side factors negatively affecting property price appreciation.Footnote 10

Accounting for the Great Recession

Our study period overlaps the Great Recession. To alleviate concerns that our results may be driven by factors related to the financial crisis, we control for the percentage change in median household income and the unemployment rate. We obtain county level data, re-do the analyses and report the results in Table 5. The median household income and unemployment data is defined annually at the county level for each year of our sample period.Footnote 11 Note that we include a two-way interaction for purchase-year-quarter and sale-year-quarter to account for area-specific trends instead of a three-way interaction that includes the county code as including the three-way interaction will result in the income and unemployment variables being dropped from the model since the data is at the county-year level. As in the main specification in Table 4, the coefficients of the variables of interest are negative and statistically significant.

As a further robustness check, we split the data into a pre-2008 and post-2008 period and re-do the analyses. Panel A of Table 6 presents the regression results based on repeat sales that have a purchase and sale date that occurred until 2008. Panel B presents the results based on repeat sales that have a purchase and sale date that occurred after 2008. We note that our findings are robust to data subsets from different time periods.

Endogenous Self-Selection by Distributor-Pharmacies

We account for concerns that vertically integrated pharmacies may endogenously locate in areas with a higher demand for opioids and hence one may empirically observe a negative relation between dispense and house price growth. We identify a subset of transactions that have non-zero dispense for such pharmacies. These transactions involve dispense by vertically integrated pharmacies and are relatively more homogeneous in terms of the location choice, i.e. involve areas where vertically integrated pharmacies were present. Table 7 presents the regression results that is based on the subset of transactions and dispense through such distributor-pharmacies as explanatory variables. Columns 1 and 2 present the regression results for the standardized measures, \(\#Pills/\#Pharmacies\) and \(\#Pills/\#Properties\), that are based on dispense only by distributor-pharmacies. We see that the coefficients of the standardized measures are negative and statistically significant. Thus, even in a sample that only includes transactions where vertically integrated pharmacies dispensed (or located), we draw a similar inference.

Next, we account for the concern that vertically integrated pharmacies may endogenously locate in areas with a higher demand for opioids in another way by controlling for the dispense by non-distributor-dispensaries. Table 8 presents the regression results that includes \(\#Pills/\#Pharmacies\) and \(\#Pills/\#Properties\) that are based on dispense through such distributor-pharmacies and non-distributor-dispensaries as explanatory variables. The variables relating to non-distributor-dispensaries involve dispense by dispensaries that are not vertically integrated and may proxy for the demand for opioids in the area. We note that after controlling for non-distributor-dispensaries, the coefficients of \(\#Pills/\#Pharmacies\) and \(\#Pills/\#Properties\) that are based on dispense by distributor-pharmacies are negative and statistically significant. This implies that even after potentially controlling for the general demand for opioids in the area, the effect of dispense by vertically integrated pharmacies on house price growth persists.

Discussion & Concluding Remarks

Recent developments include a range of lawsuits alleging wrongdoing on the part of companies that either manufacture or distribute opioids. For instance, the Washington Post notes that two dozen companies are being sued by 2,000 towns and cities in a federal court in Cleveland.Footnote 12 The companies defend their practices and argue that pharmacies, practitioners, and customers are to blame. While such discussions focus on healthcare and policy concerns relating to the opioid crisis, our study presents evidence of opioid-related effects on the housing market. We find a significant, negative association between opioid dispense and house price appreciation. To potentially present a causal narrative that may suggest externalities, we use a measure of supply that is based on vertical integration in the supply chain. Our findings imply that a one standard deviation increase in the standardized number of pills dispensed by vertically integrated pharmacies is associated with a 5.8% decrease in house price appreciation. Our results are robust to a range of alternate explanations.

There may be demand side effects. For instance, prescription opioids may lead to other drug addictions.Footnote 13 Part of the explanation underlying our findings may be attributed to a direct effect wherein addicts potentially impose a negative externality on nearby property prices. Furthermore, there may be indirect effects from opioids on house prices due to depressed economic activity and wealth shocks. Thus, there may be a decrease in demand for housing in affected areas and hence a decline in house prices. On the other hand, opioid addiction may result in death or mortgage default from financial instability. Such outcomes may result in an increase in the supply of properties on the market and a decrease in prices that are bid. However, we leave identification of the exact underlying channel for future research.

The policy discussion on health crises has focused predominantly on direct consequences such as loss of wages, overdose deaths, etc. We show that an indirect effect arises on nearby assets, namely properties located near to focal points of an epidemic. We estimate a significant decline in the price appreciation rate of properties in affected areas. Thus, we inform the policy debate on the impact of health crises by quantifying an economic effect of the opioid epidemic. This may be more relevant in contemporaneous times as economic costs and responses to another health epidemic, COVID-19, is debated. While our work focuses on the opioid crisis, a general inference on epidemics and real estate markets may be drawn.

Notes

According to the National Institute of Health (NIH), more than 130 people die in the U.S. every day from opioid-related overdose. Drug overdose is now the leading cause of accidental death in the United States, and 80% of individuals that are addicted to heroin were first prescribed opioids for pain relief. See Addiction Center (2020), National Institutes of Health (2020a) and National Institutes of Health (2020b) for further details.

For example, Florence et al. (2016) use data on health care claims and fatality cases to estimate the cost of the opioid crisis. The authors estimate that the cost of prescription opioid overdose, abuse and dependence in the U.S. was $78.5 billion in 2013.

See Washington Post (2019b) for additional details on the data.

The Washington Post notes the following regarding the data field: “DEA calculated field indicating number of pills, patches or lozenges, among others, shipped as part of the transaction.”

Drug Rehab (2020) notes additional information on drug potency.

See National Institutes of Health (2020c) for a complete list.

We implement some data cleaning rules. For instance, we trim the sample at the top and bottom percentiles of transaction price and change in price to account for outlying observations that may skew the results.

The standard errors are clustered at the zip-code level.

The standard deviations are noted in Table 3.

We perform several robustness checks and include the results in the Appendix. We use the opioid data over the entire study period and count the number of pharmacies within 2-miles of a repeat sales property to generate a standardized measure of the number of pills dispensed. There may be concerns relating to endogenous opening or closing of dispensaries influencing the results. Table 9 presents regression results based on a subset of transactions that did not involve any openings or closings. We note a similar inference as before. There may be considerable differences in areas that dispense opioids relative to those that do not. We repeat our analysis for the sample of repeat sales in high volume opioid areas, i.e., areas above the 25th-percentile of dispense (The main results involve repeat sales across all areas). Table 10 presents the regression results and we see that the overall inference remains unchanged. Lastly, we account for outliers due to either a very high or low amount of dispense by dispensaries or in specific areas by re-doing the analysis for a subset of repeat sale transactions that involve dispense between the top and bottom percentile of the distribution of dispense. The results are presented in Table 11 and the inference is robust to the exclusion of potential outliers.

The U.S. Census Bureau’s Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates program produces single-year estimates of income and poverty for all U.S. states and counties as well as estimates of school-age children in poverty for all 13,000+ school districts. The Local Area Unemployment Statistics (LAUS) program produces monthly and annual employment, unemployment, and labor force data for Census regions and divisions, states, counties, metropolitan areas, and many cities, by place of residence.

Washington Post (2019c) notes further details.

See Addiction Center (2020) for an additional discussion on opioid consumption leading to other drug addictions.

References

Addiction Center (2020). The Opioid Epidemic. Available at https://www.addictioncenter.com/opiates/opioid-epidemic/.

Bailey, M. J., Muth, R. F., & Nourse, H. O. (1963). A Regression Method for Real Estate Price Index Construction. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 58(304), 933–942.

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2020). Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Case, K. E., & Shiller, R. (1989). The Efficiency of the Market for Single Family Homes. American Economic Review, 79(1), 125–37.

Cepeda, M. S., Fife, D., Yuan, Y., & Mastrogiovanni, G. (2013). Distance traveled and frequency of interstate opioid dispensing in opioid shoppers and nonshoppers. Journal of Pain, 14(10), 1158–1161.

Custodio, C., Cvijanovic, D., and Wiedemann, M. (2021). Opioid crisis and real estate prices.

D’Lima, W., Lopez, L.A., and Pradhan, A. (2020). COVID-19 and housing market effects: Evidence From US Shutdown Orders. Available at SSRN 3647252.

Drug Rehab (2020). Strongest Pain Pills. Available at https://www.drugrehab.com/addiction/opioid-strength/.

Edlund, M. J., Martin, B. C., Russo, J. E., DeVries, A., Braden, J. B., & Sullivan, M. D. (2014). The role of opioid prescription in incident opioid abuse and dependence among individuals with chronic non-cancer pain: the role of opioid prescription. The Clinical journal of pain, 30(7), 557.

Elul, R., Souleles, N. S., Chomsisengphet, S., Glennon, D., & Hunt, R. (2010). What “triggers” mortgage default? American Economic Review, 100(2), 490–94.

Evans, W.N. and Lieber, E.M.J. (2019). Origins of the Opioid Crisis and Its Enduring Impact. NBER Working Paper.

Florence, C., Luo, F., Xu, L., & Zhou, C. (2016). The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse and dependence in the United States, 2013. Medical care, 54(10), 901.

Francke, M. and Korevaar, M. (2020). Housing markets in a pandemic: Evidence from historical outbreaks. Available at SSRN 3566909.

Kenan, K., Mack, K., & Paulozzi, L. (2012). Trends in prescriptions for oxycodone and other commonly used opioids in the United States, 2000–2010. Open Medicine, 6(2), 41–47.

Ling, D. C., Wang, C., & Zhou, T. (2020). A First Look at the Impact of COVID-19 on Commercial Real Estate Prices: Asset-Level Evidence. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 10(4), 669–704.

National Institutes of Health (2020a). Opioid addiction. Available at https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/opioid-addiction#statistics.

National Institutes of Health (2020b). Opioid Overdose Crisis. Available at https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis.

National Institutes of Health (2020c). Opioid Summaries by State. Available at https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-summaries-by-state.

Tyndall, J. (2019). Getting high and low prices: Marijuana dispensaries and home values. Real Estate Economics.

Washington Post (2019a). At height of crisis, Walgreens handled nearly one in five of the most addictive opioids. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/2019/11/07/height-crisis-walgreens-handled-nearly-one-five-most-addictive-opioids/.

Washington Post (2019b). Drilling into the DEA’s pain pill database. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/investigations/dea-pain-pill-database/.

Washington Post (2019c). Five takeaways from the DEA’s pain pill database. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/six-takeaways-from-the-deas-pain-pill-database/2019/07/16/1d82643c-a7e6-11e9-a3a6-ab670962db05_story.html.

Wong, G. (2008). Has SARS infected the property market? Evidence from Hong Kong. Journal of Urban Economics, 63(1), 74–95.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors thank an anonymous referee for insightful comments. The authors thank the Washington Post for providing access to the opioid transaction data. Data provided by Zillow through the Zillow Transaction and Assessment Dataset (ZTRAX). More information on accessing the data can be found at http://www.zillow.com/ztrax. The results and opinions are those of the authors and do not reflect the position of Zillow Group.

Appendix A Additional Tables

Appendix A Additional Tables

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

D’Lima, W., Thibodeau, M. Health Crisis and Housing Market Effects - Evidence from the U.S. Opioid Epidemic. J Real Estate Finan Econ 67, 735–752 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-021-09884-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-021-09884-8