Abstract

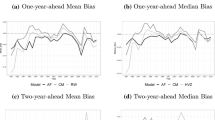

The accounting literature has used the midpoint of range forecasts in various research settings, assuming that the midpoint is the best proxy for managers’ earnings expectations revealed in range forecasts. We argue that given managers’ asymmetric loss functions regarding earnings surprises, managers are unlikely to place their true earnings expectations at the midpoint of range forecasts. We predict that managers’ true expectations are close to the upper bound of range forecasts. We find evidence consistent with these predictions in 1996–2010, especially in the recent decade. Despite their role as sophisticated information intermediaries, analysts barely unravel the pessimistic bias that managers embed in range forecasts. Furthermore, we find that the upper bound rather than the midpoint better represents investors’ interpretation of managers’ expectations in recent times. Our study cautions researchers to refine their research designs that use management range forecasts and sheds light on the role of financial analysts in the earnings expectations game.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The midpoint assumption is so appealing that it is sometimes explicitly used by information intermediaries and the press. For example, in a Wall Street Journal article by Maxwell Murphy on Nov. 2, 2011, “CFO Journal: The big number,” the author compares corporate guidance with analyst consensus and writes, “Where companies have issued a range of earnings expectations, Fac[t]Set uses the midpoint of the guidance range for comparison with the Wall Street consensus.” Here, FactSet is a financial data service provider to investment professionals.

Baginski et al. (1993) conduct validity checks of this assumption in their appendix and use a parametric sign test for robustness checks of their measurement of management forecast news.

We choose quarterly data over annual data because the MBE pressure is quarterly, and when annual earnings are finally reported, three quarters of the performance have already been public for months. In untabulated analysis, we find that the results from annual data are qualitatively similar but noisier.

We discuss in Sect. 4.4 that in recent times managers tend to predict street earnings instead of GAAP earnings and that managers’ strategic use of range forecasts is motivated by street earnings rather than GAAP earnings beating market expectations.

For example, range forecasts account for only 6.8 % of the earnings forecasts during 1979–1987 collected by Pownall et al. (1993) and 20–24 % of the forecasts during 1983–1986 collected by Baginski et al. (1993) and Baginski and Hassell (1997) and during 1981–1991 collected by Bamber and Cheon (1998). The percentage of range forecasts increases to 40 % in 2000 and 82 % in 2004 (Choi et al. 2010).

Hirst et al. (1999) and Libby et al. (2006) specifically examine range forecasts in an experimental setting. They construct all range forecasts with the midpoint coinciding with the point forecasts and inform the subjects that past forecast errors are unbiased. These research designs do not allow intentional bias to exist in their experiments.

We perform additional analyses that help mitigate the concern that this assumption may not hold. Prior research has used actual earnings as a proxy for managers’ private expectations. For example, Cotter et al. (2006) compare the prevailing analyst consensus with actual earnings to determine whether managers perceive analyst forecasts to be optimistic.

The phenomenon of whisper forecasts attests to this conjecture. Analysts issue earnings forecasts to be included in the analyst consensus but whisper to their clients forecasts that are much higher than their official forecasts (Bagnoli et al. 1999).

The tenor of the results remains largely unchanged if we examine forecasts issued between the date of the first analyst revision after the prior quarter’s earnings announcement and the current quarter’s earnings announcement.

The management earnings forecast data are not split-adjusted. Analyst forecasts and actuals are from the IBES non-split-adjusted database. We adjust management forecasts, analyst forecasts, and actual earnings by the split factor in CRSP when necessary as recommended by Robinson and Glushkov (2006).

Forecasts are “point” if the CIG CODE is A, B, F, G, H, I, O, or Z and EST_1 contains a numerical estimate and EST_2 is missing or EST_1 and EST_2 have the same numerical estimates. Forecasts are “range” if the CIG CODE is B, F, G, H, O or Z and EST_1 and EST_2 contain different numerical estimates. Forecasts are “min” if the CIG CODE is 3, 5, 7, C, E, M, P, V, or Y and EST_1 contains a numerical estimate. Forecasts are “max” if the CIG CODE is 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, D, J, K, L, U, W, or X and EST_1 contains a numerical estimate. Forecasts are “qualitative” if the CIG CODE is N, Q, R, S, or T or EST_1 and EST_2 do not contain numerical estimates.

Maximum, minimum, and qualitative forecasts are far less common in recent years than in the 1970s and 1980s. Pownall et al. (1993) report that 69.4 % of quantitative management earnings forecasts in 1979–1987 are maximums or minimums. From hand-collected data in 2006–2007, Lansford et al. (2012) observe that 1.9 % are maximum or minimum, 5.2 % are qualitative, and 4.3 % are ambiguous (e.g., “We expect earnings growth to be in the single digits”).

In untabulated analysis, we observe that point forecasts also show evidence of a pessimistic bias versus actual earnings, but the percentage of actual earnings being higher or equal to the point forecast is fairly constant during our sample period. Because point forecasts have decreased to only 10 % of management forecasts, we do not examine bias of point forecasts in this study.

Throughout the paper, we conduct mean tests in regressions with a constant and use robust standard errors clustered by firm. We conduct median tests in median regressions with a constant.

This result is consistent with the reported summary statistics of Baik and Jiang (2006) for their sample period of 1995–2002, when they calculate management forecast bias using the midpoint for range forecasts.

We observe stickiness in the use of range forecasts from quarter to quarter (89 %) as well as within the same quarter (84 %).

In an untabulated multivariate analysis, we regress ACT_DIS on several variables related to incentives for managers’ strategic behavior. We continue to find large firm size and high growth to be associated with forecast pessimism. After controlling for the width of forecast range, high earnings uncertainty is associated with increased forecast pessimism, consistent with managers erring on the side of caution in an uncertain environment given their asymmetric loss functions.

In untabulated analyses, we partition the sample by the width of forecast range (“wide” for the top quartile, “medium” for the middle two quartiles, and “narrow” for the bottom quartile) and find that our primary findings hold for each partition, although the results are least strong for the “wide” partition perhaps because larger width tends to be used earlier in the fiscal period when managers’ strategic incentives are weakest. We identify an unambiguously good-news sample (forecasts with the lower bound above the prevailing analyst consensus) and an unambiguously bad-news sample (forecasts with the upper bound below the prevailing analyst consensus) and find that our primary findings hold for each sample and that the good-news sample exhibits a larger pessimistic bias than the bad-news sample in the past decade, consistent with managers preferring to conservatively raise analyst expectations.

The primary sources of the management earnings forecasts are Business Wire, PR Newswire, and FD Wire.

A forecast is classified as “street earnings forecast” if the company explicitly excludes certain earnings items from the forecast or uses terms such as “adjusted earnings,” “operating earnings,” and “EBIDA.” A forecast is classified as “GAAP earnings forecast” if the company uses terms such as “reported earnings” and “GAAP earnings” or if exclusions are absent. The classification is unclear when on the one hand the company’s press release does not mention any earnings exclusions or use any specific earnings terms but on the other hand the press article immediately discussing the forecast compares it with the analyst consensus.

Our validation check does not rule out the possibility that managers’ and analysts’ definitions of street earnings may differ.

In Table 2 ACT_DIS is left skewed, and its median is close to 0 for this period, indicating that only some management forecasts are very optimistic.

The finding that in the earlier sample period management news calculated from the upper bound better explains stock returns than that from the midpoint is inconsistent with our finding in Sect. 4 that actual earnings largely fall near the midpoint in this period. The inconsistency could be due to investors’ interpreting range forecasts rather optimistically in the booming economic period or to different forecast samples used in the two sections.

References

Ajinkya, B. B., Bhojraj, S., & Sengupta, P. (2005). The association between outside directors, institutional investors, and the properties of management earnings forecasts. Journal of Accounting Research, 43, 343–376.

Anilowski, C., Feng, M., & Skinner, D. (2007). Does earnings guidance affect market returns? The nature and information content of aggregate earnings guidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 44, 36–63.

Athanasakou, V., Strong, N. C., & Walker, M. (2011). The market reward for achieving analyst earnings expectations: Does managing expectations or earnings matter? Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 38, 58–94.

Baginski, S. P., Conrad, E. J., & Hassell, J. M. (1993). The effects of management forecast precision on equity pricing and on the assessment of earnings uncertainty. The Accounting Review, 68, 913–927.

Baginski, S. P., & Hassell, J. M. (1997). Determinants of management forecast precision. The Accounting Review, 72, 303–312.

Baginski, S. P., Hassell, J. M., & Wieland, M. M. (2011). An examination of the effects of management earnings forecast form and explanations on financial analyst forecast revisions. Advances in Accounting, Incorporating Advances in International Accounting, 27, 17–25.

Bagnoli, M., Beneish, M. D., & Watts, S. (1999). Whisper forecasts of quarterly earnings per share. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 28, 27–50.

Baik, B., & Jiang, G. (2006). The use of management forecasts to dampen analysts’ expectations. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 25, 531–553.

Bamber, L., & Cheon, S. (1998). Discretionary management earnings forecast disclosures: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Accounting Research, 36, 167–190.

Bartov, E., Givoly, D., & Hayn, C. (2002). The rewards to meeting or beating earnings expectations. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33, 173–204.

Bernard, V. L., & Thomas, J. K. (1989). Post-earnings announcement drift: Delayed price response or risk premium? Journal of Accounting Research, 27, 1–36.

Beyer, A., Cohen, D., Lys, T., & Walther, B. (2010). The financial reporting environment: Review of the recent literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50, 296–343.

Bradshaw, M. T., & Sloan, R. (2002). GAAP versus the street: An empirical assessment of two alternative definitions to earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 41–66.

Brown, L. D., & Caylor, M. L. (2005). A temporal analysis of quarterly earnings thresholds: Propensities and valuation consequences. The Accounting Review, 80, 423–440.

Choi, J., Myers, L. A., Zang, Y., & Ziebart, D. A. (2010). The roles that forecast surprise and forecast error play in determining management forecast precision. Accounting Horizons, 24, 165–188.

Christensen, T. E., Merkley, K. J., Tucker, J. W., & Venkataraman, S. (2011). Do managers use earnings guidance to influence street earnings exclusions? Review of Accounting Studies, 16, 501–527.

Cotter, J., Tuna, I., & Wysocki, P. (2006). Expectations management and beatable targets; How do analysts react to explicit earnings guidance? Contemporary Accounting Research, 23, 593–624.

Daily, R. A. (1971). The feasibility of reporting forecasted information. The Accounting Review, 46, 686–692.

De Bondt, W., & Thaler, R. (1985). Does the stock market overreact? Journal of Finance, 40, 793–805.

Dechow, P., Richardson, S., & Tuna, I. (2003). Why are earnings kinky? An examination of the earnings management explanation. Review of Accounting Studies, 8, 354–384.

Du, N., Budescu, D., Shelly, M. K., & Omer, T. C. (2011). The appeal of vague financial forecasts. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 14, 179–189.

Feng, M., & Koch, A. (2010). Once bitten, twice shy: The relation between outcomes of earnings guidance and management guidance strategy. The Accounting Review, 85, 1951–1984.

Gong, G., Li, L. Y., & Wang, J. J. (2011). Serial correlation in management earnings forecast errors. Journal of Accounting Research, 49, 677–720.

Gong, G., Li, L. Y., & Xie, H. (2009). The association between management earnings forecast errors and accruals. The Accounting Review, 84, 497–530.

Graham, J. R., Harvey, C., & Rajgopal, S. (2005). The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40, 3–73.

Hirst, D. E., Koonce, L., & Miller, J. (1999). The joint effect of management’s prior forecast accuracy and the form of its financial forecasts on investor judgment. Journal of Accounting Research, 37, 101–124.

Hirst, D. E., Koonce, L., & Venkataraman, S. (2008). Management earnings forecasts: A review and framework. Accounting Horizons, 22, 315–338.

Hui, K. W., Matsunaga, S., & Morse, D. (2009). The impact of conservatism on management earnings forecasts. Journal of Accounting Economics, 47, 191–207.

Ke, B., & Yu, Y. (2006). The effect of issuing biased earnings forecasts on analysts’ access to management and survival. Journal of Accounting Research, 44, 965–999.

Kennedy, J., Mitchell, T., & Sefcik, S. (1998). Disclosure of contingent environmental liabilities: Some unintended consequences. Journal of Accounting Research, 36, 257–278.

Kim, Y., & Park, M. S. (2012). Are all management earnings forecasts created equal? Expectations management versus communication. Review of Accounting Studies, 17, 807–847.

Koh, K., Matsumoto, D. A., & Rajgopal, S. (2008). Meeting or beating analyst expectations in the post-scandals world: Changes in stock market rewards and managerial actions. Contemporary Accounting Research, 25, 1–39.

Lansford, B., Lev, B., & Tucker, J. (2012). Causes and consequences of disaggregating earnings guidance. Journal of Business, Finance and Accounting, 40, 26–54.

Lee, C. M. (2001). Market efficiency and accounting research: A discussion of ‘capital market research in accounting’ by S.P. Kothari. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31, 233–253.

Libby, R., Tan, H., & Hunton, J. E. (2006). Does the form of management’s earnings guidance affect analysts’ earnings forecasts? The Accounting Review, 81, 207–225.

Lim, T. (2001). Rationality and analysts’ forecast bias. Journal of Finance, 56, 369–385.

Matsumoto, D. A. (2002). Management’s incentives to avoid negative earnings surprises. The Accounting Review, 77, 483–514.

Matsunaga, S., & Park, C. (2001). The effect of missing a quarterly earnings benchmark on the CEO’s annual bonus. The Accounting Review, 76, 313–332.

Mayew, W. J. (2008). Evidence of management discrimination among analysts during earnings conference calls. Journal of Accounting Research, 46, 627–659.

McDonald, C. L. (1973). An empirical examination of the reliability of published predictions of future earnings. The Accounting Review, 48, 502–510.

McNichols, M. (1989). Evidence of informational asymmetries from management earnings forecasts and stock returns. The Accounting Review, 64, 1–27.

Mergenthaler, R., Rajgopal, S., & Srinvasan, S. (2011). CEO and CFO career penalties to missing quarterly analyst forecasts. Working paper, Emory University.

Muth, J. F. (1961). Rational expectations and the theory of price movements. Econometrica, 29, 315–335.

Ng, J., Tuna, I., & Verdi, R. (2013). Management forecast credibility and underreaction to news. Review of Accounting Studies, 18, 956–986.

Oliver, B. (1972). A study of confidence interval financial statements. Journal of Accounting Research, 10, 154–166.

Pownall, G., Walsley, C., & Waymire, G. (1993). The stock price effects of alternative types of management earnings forecasts. The Accounting Review, 68, 896–912.

Richardson, S., Teoh, S. H., & Wysocki, P. (2004). The walk-down to beatable analyst forecasts: The role of equity issuance and insider trading incentives. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21, 885–924.

Robinson, D., & Glushkov, D. (2006). A note on IBES unadjusted data. Working paper, Wharton Research Data Services.

Rogers, J. L., & Stocken, P. C. (2005). Credibility of management forecasts. The Accounting Review, 80, 1233–1260.

Sheffrin, S. M. (1996). Rational expectations. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Simon, H. A. (1955). A behavioral model of rational choice. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69, 69–118.

Simon, H. A. (1959). Theories of decision-making in economics and behavioral science. The American Economic Review, 49, 253–283.

Skinner, D. J., & Sloan, R. G. (2002). Earnings surprises, growth expectations, and stock returns or don’t let an earnings torpedo sink your portfolio. Review of Accounting Studies, 7, 289–312.

Soffer, L. C., Thiagarajan, S. R., & Walther, B. R. (2000). Earnings preannouncement strategies. Review of Accounting Studies, 5, 5–26.

Tucker, J. W. (2010). Is silence golden? Earnings warnings and change in subsequent analyst following. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 25, 431–456.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1982). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, P. (1996). The relation between prior earnings forecasts by management and analyst response to a current management. The Accounting Review, 71, 103–115.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rajiv Banker, Larry Brown, Dmitri Byzalow, Michael Drake, David Folsom, Joost Impink, Stephen Penman (editor), Kathy Rupar, Michael Tang, Angie Wang, an anonymous referee, and the participants at the 2012 AAA Annual Meeting, the University of Florida Accounting Brown Bag, and the University of Temple Accounting Workshop. Marcus Kirk thanks the Luciano Prida Professorship Foundation, and Jennifer Tucker thanks the J. Michael Cook/Deloitte Professorship Foundation for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ciconte, W., Kirk, M. & Tucker, J.W. Does the midpoint of range earnings forecasts represent managers’ expectations?. Rev Account Stud 19, 628–660 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-013-9259-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-013-9259-2