Abstract

An earnings surprise can be caused by a combination of firm-specific factors and market or industry factors. We hypothesize that managers have an incentive to time their warnings to occur soon after their industry peers’ warnings to minimize their apparent responsibility for earnings shortfalls. Using duration analysis, we find that firms accelerate their warnings in response to peer firms’ warnings. We conduct several tests to control for alternative explanations for warning clustering (for example, common shocks and information transfer) and conclude that the observed clustering is primarily due to herding. Our study is one of the first to empirically examine managers’ herding behavior and the first to document clustering of bad news. Moreover, we provide a multi-firm perspective on managers’ disclosure decisions that alerts researchers to consider or control for herding when they examine other determinants of managers’ disclosure decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Our sample selection is consistent with the warning studies by Kasznik and Lev (1995), Soffer et al. (2000), and Atiase et al. (2006). These studies identify warnings as unfavorable earnings disclosures issued in the 60-day window before earnings announcement. Because earnings are typically announced 25–30 days after the fiscal quarter end, the starting point from when these studies collect warnings is close to the beginning of the third fiscal month.

On average, seven warnings are issued for an industry-quarter. If a uniform distribution is assumed, the average interval between successive warnings should be about 9 days.

The persistence of an earnings shortfall is likely to be unrelated to whether it is caused by internal or external factors. For example, an economic recession and a change in the management could both have long-lasting effects.

The accounting literature has a stream of information transfer studies. A firm’s earnings forecast conveys information that affects nonforecasting industry peers’ returns (Baginski 1987; Han et al. 1989). Early earnings announcements affect the stock returns of late announcers in the industry (Foster 1981; Clinch and Sinclair 1987; Han and Wild 1990; Freeman and Tse 1992; Lang and Lundholm 1996b). The major difference between managerial herding and information transfer is that the former focuses on managers’ decisions in a multi-firm setting, whereas the latter focuses on investors’ inferences in a multi-firm setting.

Evaluators use the “covariation” of behaviors from several individuals and sources to identify possible causes.

Our conjecture about managers’ behavior does not necessarily imply that boards of directors are misled. Managers and their evaluators may be linked by interlocking directorships (Brick et al. 2006) and social ties (Hwang and Kim 2008). Issuing a warning in a cluster would enable the evaluators to justify attributing an unwarranted proportion of the shortfall to external factors even though the evaluators can see through the manager’s timing strategy.

The term “duration model” is used in engineering for models that examine the timing of mechanical failures (Greene 2003, 790–791). Biomedical research has a longer history of using this method and refers to it as “survival analysis.” Duration models have been applied in economics to examine the length of unemployment spells and in finance and accounting to study the staging of venture capital (Gompers 1995), earnings management (Beatty et al. 2002), and the influence of investment banking ties on the speed of changes in analysts’ recommendations (O’Brien et al. 2005).

Right-censoring means that the measurement for duration does not end naturally but ends early because of either researchers’ constraints or an outside force. In our setting, warning duration is right-censored at the earnings announcement date (strictly speaking, 3 days before the earnings announcement date).

We assume that at the beginning of the third fiscal month, a firm has decided whether to warn and the only remaining decision is when to warn.

The model is \( h(t_{i} ) = h_{0} (t_{i} )\;\exp {\kern 1pt} (X_{i} \beta ) \). Suppose a set of sample firms in one industry issues warnings on K different dates (\( T_{1} ,T_{2} ,T_{3} , \ldots ,T_{k} \)) for a quarter and that there is at most one warning each day. Let \( R_{i} \) be the set of firms that have not yet issued a warning by day\( T_{i} \), where \( i = 1,2, \ldots ,k \). The probability that a firm warns on day \( T_{i} \) is \( {{\exp (X_{i} \beta )} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\exp (X_{i} \beta )} {\sum\nolimits_{{j \in R_{i} }} {\exp (X_{j} \beta )} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\sum\nolimits_{{j \in R_{i} }} {\exp (X_{j} \beta )} }} \). Then, \( \;LnL(\beta |data) = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{k} {\left[ {X_{i} \beta - \ln \left( {\sum\nolimits_{{j \in R_{i} }} {\exp (X_{j} \beta )} } \right)} \right]} \)is the partial log-likelihood of observing the data, and the Cox estimator for β maximizes this function (Cox 1975).

We obtain similar results when PeerWarn (t) is measured in a 3-, 7-, or 10-day interval.

Brown et al. (2006) use the cumulative proportion of industry peers that have disclosed by day t as the primary variable of interest. We use the number of recent warnings by peer firms in the preceding 5 days as our primary explanatory variable because the measure best reflects our expectation that managers seek to reduce the blame for poor performance by issuing warnings at about the same time as other firms with earnings disappointments.

Within-sample rankings would be coarse for industry quarters that have only a few warnings.

We rank BadNews in the full warning sample, not among warning firms in the industry-quarter, because the rankings under the latter approach would be coarse for industry quarters that have only a few warnings.

First Call uses analysts’ earnings expectations as the benchmark to code managers’ earnings guidance as positive, negative, or in-line guidance. Although the data manual does not specify how guidance with a range estimate is coded, we infer based on the comparison of the estimates and analysts’ consensus that CIG codes guidance as “negative” if the upper estimate is lower than analyst consensus, “positive” if the lower estimate is higher than analyst consensus, and “in-line” if analyst consensus is between the lower and upper estimates.

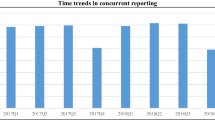

The period begins in 1996 because there are only a few observations (328 events) before 1996 and because the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 substantially expanded the safe-harbor protection to firms for disclosing forward-looking information.

To demonstrate managers’ differential forecasting ability in the two windows (waves), we compare the incidence of point vs. range forecasts across the windows. While only 29.1% of the earnings forecasts are point estimates, the percentage is substantially larger at 39.3% for earnings warnings. If we treat a point estimate as having zero range, the median range of earnings warning estimates as a percentage of the absolute value of the mean forecast is 6.1%, whereas that of earnings forecasts is 9.3%. The difference is both economically and statistically significant (Wilcoxon Z = 8.07).

The warnings are issued by 1,817 unique firms. Among these firms, 919 (50.6%), 465 (25.6%), 225 (12.4%), 107 (5.9%), and 101 (5.5%) issued warnings once, twice, three, four, and five or more times, respectively.

We also estimate an OLS model with the logarithm of the actual duration as the dependent variable and PeerWarn(Actual) instead of PeerWarn(t) as the explanatory variable. The coefficient on PeerWarn(Actual) is −0.039 (t = −6.22), consistent with the Cox model results, and the model R 2 is 21.2 % (recall that duration is inversely related to hazard rate).

We also measure bad news as the absolute price-deflated difference between the firm’s EPS estimate (or the midpoint for a range estimate) and the most recent consensus before the warning. We substitute the realized earnings for company estimate when the latter is not in point or range form. The coefficient on BadNews is significantly negative (coefficient = −0.016, z-statistic = −2.18). Of our sample firms, 28.6, 64.6, and 6.8% provide point, range, and other-form warnings, respectively.

In an unreported robustness test, we separate the sample into pre- and post-FD subsamples and find no difference in warning clustering, though warnings are weakly more timely in the post-FD in a one-tailed test (z = 1.61).

We construct a variable that counts the number of warnings in the 5-day window before the sample’s warning issued by firms in industries other than the sample firm’s. We find no association between this variable and warning timeliness, whereas PeerWarn(t) remains significantly positively associated with warning timeliness. This result is consistent with our message of within-industry herding.

Some industry-dummy coefficients have different signs than those in Table 5. As is typical for panel data, our interest is in controlling for the fixed industry effects, not in making inferences from their coefficients.

The 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles of the distribution of events per industry quarter for the bad-news sample are 3, 5, 8, and 20, whereas those for the good-news sample are 3, 4, 5, and 12. To match with the good-news sample distribution, we exclude from the bad-news sample the industry quarters with 12 or more warnings. The reduced bad-news sample contains 1,881 events from 449 industry quarters and the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of the distribution of the number of events per industry quarter are comparable with those of the good-news sample. We then randomly choose 115 industry quarters to mimic the sample size of good news, leading to 500 warning followers.

We speculate that the reduced z statistic is due to less variation in PeerWarn(t) after the industry quarters with more than 12 events are excluded.

We find few good-news alerts in warning clusters or within 5 days after the last warning in a cluster (unreported), consistent with bad-news herding.

Our approach treats each industry as one entity and prevents firm-level ROA outliers from driving the industry-level ROA.

On the other hand, later warnings have larger earnings shortfalls than early ones (Row 2), so the total market reaction to later firms should be larger. To examine the aggregate return effect, we collect market-adjusted returns from the day after the analyst consensus for the leader to the sample firm’s own warning date (included). After controlling for earnings surprise, we find no difference in stock returns across firms of different warning sequence.

Although our primary goal is to document the existence of warning herding, we conduct preliminary tests to determine whether herding managers have stronger career concerns than nonherding managers. We use the CEO’s age as a proxy for career concerns because the younger a manager, the longer his future earnings stream, and thus the greater his concern about others’ perceptions of his ability (Gibbons and Murphy 1992; Garen 1994; Bryan et al. 2000). We obtain CEO age data for 2,977 of the 3,016 warning followers (98.7%). We retrieve data for 1,430 observations from Compustat’s executive compensation database and hand-collect data for the remaining 1,547 observations from DEF 14A proxy statements. This sample is comprised of 1,699 herders (those in the middle or at the tail of a warning cluster) and 1,278 nonherders. We find that the average CEO age is 53.6 for the herding group and 54.6 for the non herding group. The CEOs are younger in herding firms than in nonherding firms in both a t-test (t = 3.78) and a nonparametric Wilcoxon test (z = 3.70). This result is consistent with career concerns motivating warning herding.

References

Aboody, D., Barth, M. E., & Kasznik, R. (2004). Firms’ voluntary recognition of stock-based compensation expense. Journal of Accounting Research, 42(2), 123–150.

Acharya, V. V., DeMarzo, P., & Kremer, I. (2008). Endogenous information flows and the clustering of announcements. Working paper. New York University. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1275133.

Anilowski, C., Feng, M., & Skinner, D. (2007). Does earnings guidance affect market returns? The nature and information content of aggregate earnings guidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 44(1–2), 36–63.

Arya, A., & Mittendorf, B. (2005). Using disclosure to influence herd behavior and alter competition. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40(1–3), 231–246.

Atiase, R. K., Supattarakul, S., & Tse, S. (2006). Market reaction to earnings surprise warnings: The incremental role of shareholder litigation risk on the warning effect. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 21(2), 191–222.

Avery, C., & Zemsky, P. (1998). Multimensional uncertainty and herd behavior in financial markets. The American Economic Review, 88(4), 724–748.

Baginski, S. P. (1987). Intraindustry information transfers associated with management forecasts of earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 25(2), 196–216.

Baginski, S. P., Hassell, J., & Hillison, W. A. (2000). Voluntary causal disclosures: Tendencies and capital market reaction. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 15, 371–389.

Baginski, S. P., Hassell, J., & Kimbrough, M. (2002). The effect of legal environment on voluntary disclosure: Evidence from management earnings forecasts issued in U.S. and Canadian markets. The Accounting Review, 77(1), 25–50.

Baginski, S. P., Hassell, J., & Pagach, D. (1995). Further evidence on nontrading-period information release. Contemporary Accounting Research, 12(1), 207–221.

Banerjee, A. V. (1992). A simple model of herd behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(3), 797–817.

Beatty, A. L., Ke, B., & Petroni, K. R. (2002). Earnings management to avoid earnings declines across publicly and privately held banks. The Accounting Review, 77(3), 547–570.

Bhojraj, S., Lee, C. M. C., & Oler, D. K. (2003). What’s my line? A comparison of industry classification schemes for capital market research. Journal of Accounting Research, 41(5), 745–774.

Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., & Welch, I. (1992). A theory of fads, fashion, custom, and cultural change as informational cascades. Journal of Political Economy, 100(5), 992–1026.

Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., & Welch, I. (1998). Learning from the behavior of others: Conformity, fads, and informational cascades. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(3), 151–170.

Brick, I. E., Palmon, O., & Wald, J. K. (2006). CEO compensation, director compensation, and firm performance: Evidence of cronyism? Journal of Corporate Finance, 12(3), 403–423.

Brown, C. N., Gordon, L. A., & Wermers, R. R. (2006). Herd behavior in voluntary disclosure decisions: An examination of capital expenditure forecasts. Working paper. University of Southern California. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=649823.

Bryan, S., Hwang, L., & Lilien, S. (2000). CEO stock-based compensation: An empirical analysis of incentive-intensity, relative mix, and economic determinants. Journal of Business, 73(4), 661–693.

Chamley, C., & Gale, D. (1994). Information revelation and strategic delay in a model of investment. Econometrica, 62(5), 1065–1085.

Clement, M., & Tse, S. (2005). Financial analyst characteristics and herding behavior in forecasting. Journal of Finance, 40(1), 307–341.

Clinch, G. J., & Sinclair, N. A. (1987). Intra-industry information releases: A recursive systems approach. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 9(1), 89–106.

Cox, D. R. (1975). Partial Likelihood. Biometrika, 62(2), 269–276.

Darrough, M. N., & Stoughton, N. M. (1990). Financial disclosure policy in an entry game. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 12(1–3), 219–243.

Dontoh, A. (1989). Voluntary disclosure. Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance, 4(4), 480–511.

Dye, R. A. (1985). Disclosure of nonproprietary information. Journal of Accounting Research, 23(1), 123–145.

Dye, R. A., & Sridhar, S. S. (1995). Industry-wide disclosure dynamics. Journal of Accounting Research, 33(1), 157–174.

Eysenck, M. W. (2004). Psychology: An international perspective. New York: Psychology Press.

Fama, E., & French, K. (1997). Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics, 43(2), 153–193.

Field, L., Lowry, M., & Shu, S. (2005). Does disclosure deter or trigger litigation? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(3), 487–507.

Foster, G. (1981). Intra-industry information transfers associated with earnings releases. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 3(3), 201–232.

Francis, J., Philbrick, D., & Schipper, K. (1994). Shareholder litigation and corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research, 32(2), 137–164.

Freeman, R., & Tse, S. (1992). An earnings prediction approach to examining intercompany information transfers. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 15(4), 509–523.

Garen, J. E. (1994). Executive compensation and principal-agent theory. Journal of Political Economy, 102(6), 1175–1199.

Gibbons, R., & Murphy, K. M. (1992). Optimal incentive contracts in the presence of career concerns: Theory and evidence. Journal of Political Economy, 100(31), 468–505.

Gompers, P. (1995). Optimal investment, monitoring, and the staging of venture capital. Journal of Finance, 50(5), 1461–1489.

Graham, J. (1999). Herding among investment newsletters: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Finance, 54(1), 237–268.

Greene, W. (2003). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Grinblatt, M., Titman, S., & Wermers, R. (1995). Momentum investment strategies, portfolio performance, and herding: A study of mutual fund behavior. The American Economic Review, 85(5), 1088–1105.

Gul, F., & Lundholm, R. (1995). Endogenous timing and the clustering of agents’ decisions. The Journal of Political Economy, 103(5), 1039–1066.

Han, J. C. Y., & Wild, J. J. (1990). Unexpected earnings and intra-industry information transfers: Further evidence. Journal of Accounting Research, 28(1), 211–219.

Han, J. C. Y., Wild, J. J., & Ramesh, K. (1989). Managers’ earnings forecasts and intra-industry information transfers. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 11(1), 3–33.

Hwang, B.-H., & Kim, S. (2008). It pays to have friends. Journal of Financial Economics (forthcoming). http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1195313.

Johnson, M. F., Kasznik, R., & Nelson, K. K. (2001). The impact of securities litigation reform on the disclosure of forward-looking information by high technology firms. Journal of Accounting Research, 39(2), 297–327.

Jung, W., & Kwon, Y. K. (1988). Disclosure when the market is unsure of information endowment of managers. Journal of Accounting Research, 26(1), 146–153.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291.

Kasznik, R., & Lev, B. (1995). To warn or not to warn: Management disclosures in the face of an earnings surprise. The Accounting Review, 70(1), 113–134.

Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. In D. Levine (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Kelley, H. H. (1973). The process of causal attribution. American Psychologist, 28, 107–128.

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest, and money. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. Republished by Prometheus Books, New York, 1997.

Koonce, L., & Mercer, M. (2005). Using psychology theories in archival financial accounting research. Journal of Accounting Literature, 24, 175–214.

Lang, M., & Lundholm, R. (1996a). Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. The Accounting Review, 71(4), 467–492.

Lang, M., & Lundholm, R. (1996b). The relation between security returns, firm earnings, and industry earnings. Contemporary Accounting Research, 13(2), 607–629.

Lin, D. Y., & Wei, L. J. (1989). The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 84(408), 1074–1078.

Morck, R., Yeung, B., & Yu, W. (2000). The information content of stock markets: Why do emerging markets have synchronous stock price movements? Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1–2), 215–260.

Nofsinger, J. R., & Sias, R. W. (1999). Herding and feedback trading by institutional and individual investors. Journal of Finance, 54(6), 2263–2295.

O’Brien, P., McNichols, M., & Lin, H.-W. (2005). Analyst impartiality and investment banking relationships. Journal of Accounting Research, 45(4), 623–650.

Piotroski, J. D., & Roulstone, D. T. (2004). The influence of analysts, institutional investors, and insiders on the incorporation of market, industry, and firm-specific information into stock prices. The Accounting Review, 79(4), 1119–1151.

Robinson, D., & Burton, D. (2004). Discretionary in financial reporting: The voluntary adoption of fair value accounting for employee stock options. Accounting Horizons, 18(2), 97–108.

Scharfstein, D. S., & Stein, J. C. (1990). Herd behavior and investment. The American Economic Review, 80(3), 465–479.

Skinner, D. (1994). Why firms voluntarily disclose bad news? Journal of Accounting Research, 32(1), 38–60.

Skinner, D. (1997). Earnings disclosures and stockholder lawsuits. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 23(3), 249–282.

Soffer, L., Thiagarajan, S. R., & Walther, B. (2000). Earnings preannouncement strategies. Review of Accounting Studies, 5, 5–26.

Trueman, B. (1994). Analyst forecasts and herding behavior. Review of Financial Studies, 7(1), 97–124.

Tucker, J. W. (2007). Is openness penalized? Stock returns around earnings warnings. The Accounting Review, 82(4), 1055–1087.

Tucker, J. W. (2009). Earnings warnings and subsequent changes in analyst following. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance (forthcoming).

Verrecchia, R. E. (1983). Discretionary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 5, 179–194.

Welch, I. (2000). Herding among security analysts. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(3), 369–396.

Wermers, R. (1999). Mutual fund herding and the impact on stock prices. Journal of Finance, 54(2), 581–622.

Zhang, J. (1997). Strategic delay and the onset of investment cascades. RAND Journal of Economics, 28(1), 188–205.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chunrong Ai, Bipin Ajinkya, Nerissa Brown, Qi Chen, Michael Clement, Joel Demski, Bill Greene, Robert Knechel, Lisa Koonce, Haijin Lin, Lynn Rees, Eddie Riedl, David Sappington, John Sennetti, Wei Shen, Phil Stocken, two anonymous referees, and the participants of the University of Florida and Florida International University workshops and the 2006 AAA Mid-Year FARS Conference. We thank Hadi Nosseir for excellent research assistance and Thomson Financial for providing us with the First Call Company Issued Guidelines (CIG) data. Jenny Tucker thanks the Luciano Prida, Sr. Professorship Foundation for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

See Table 10.

Appendix B

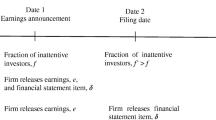

2.1 Warning leader vs. followers

We test the factors that distinguish a warning leader from its followers in a logit model:

Leader is 1 if a firm issues the first warning in the industry for the event quarter and 0 otherwise. Size, BadNews, Analyst, and MarketShare are as defined in the duration analysis in the main text of the paper. We additionally include PastLeader, FQE, and Group.

Firms’ disclosure practices tend to be sticky (Lang and Lundholm 1996a). We expect firms that were warning leaders in prior quarters to be more likely to warn first in the current quarter than other firms. PastLeader is 1 if a firm is the warning leader in its industry in any of the five previous quarters in which it warned and 0 otherwise.

Firms that end their fiscal quarters earlier are likely to issue warnings sooner than their peers. We define FQE as 1, 0, and −1 if a firm ends its fiscal quarter in the first, second, and third month of the calendar quarter, respectively and expect a positive coefficient.

Finally, we include the number of firms in each industry quarter cross section, Group. The larger the number of firms in an industry quarter, the less likely it is that a particular firm is the leader.

Table 11 presents the estimation results. The last two columns report the full-model results. As predicted, firm size is significantly positively associated with being the warning leader (a 1 = 0.091, z-statistic = 2.78). In the last column of the table we report the odds ratio. The odds ratio for Size is 1.095, indicating that when a firm’s size rank increases by 10%, the odds of being the warning leader are 9.5% higher. The magnitude of bad news is negatively associated with being the leader (a 2 = −0.053, z-statistic = −2.60). The coefficients on Analyst and MarketShare are insignificant, probably due to their high correlations with firm size, (See Columns 1 and 2 of Table 11 when Size is excluded.) Finally, the coefficient on PastLeader is statistically insignificant (a 5 = 0.204, z-statistic = 1.63). As expected, the coefficient on FQE is significantly positive, and the coefficient on Group is significantly negative, both merely reflecting a mechanical relationship induced by our research design.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tse, S., Tucker, J.W. Within-industry timing of earnings warnings: do managers herd?. Rev Account Stud 15, 879–914 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-009-9117-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-009-9117-4