Abstract

Purpose

PRO-cision medicine refers to personalizing care using patient-reported outcomes (PROs). We developed and feasibility-tested a PRO-cision Medicine remote PRO monitoring intervention designed to identify symptoms and reduce the frequency of routine in-person visits.

Methods

We conducted focus groups and one-on-one interviews with metastatic breast (n = 15) and prostate (n = 15) cancer patients and clinicians (n = 10) to elicit their perspectives on a PRO-cision Medicine intervention’s design, value, and concerns. We then feasibility-tested the intervention in 24 patients with metastatic breast cancer over 6-months. We obtained feedback via end-of-study surveys (patients) and interviews (clinicians).

Results

Focus group and interview participants reported that remote PRO symptom reporting could alert clinicians to issues and avoid unneeded/unwanted visits. However, some patients did not perceive avoiding visits as beneficial. Clinicians were concerned about workflow. In the feasibility-test, 24/236 screened patients (10%) enrolled. Many patients were already being seen less frequently than monthly (n = 97) or clinicians did not feel comfortable seeing them less frequently than monthly (n = 31). Over the 6-month study, there were 75 total alerts from 392 PRO symptom assessments (average 0.19 alert/assessment). Patients had an average of 4 in-person visits (vs. expected 6.5 without the intervention). Patients (n = 19/24) reported high support on the end-of-study survey, with more than 80% agreeing with positive statements about the intervention. Clinician end-of-study interviews (n = 11/14) suggested that PRO symptom monitoring be added to clinic visits, rather than replacing them, and noted the increasing role of telemedicine.

Conclusions

Future research should explore combining remote PRO symptom monitoring with telemedicine and in-person visits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Plain English Summary

Recently, there has been interest in routinely monitoring patients’ symptom reports to identify and address concerns. In this study, we aimed to develop and test an intervention where patients’ symptom reports could be used for monitoring and to avoid monthly routine in-person visits for patients who did not need or want them. We interviewed 30 patients with cancer and 10 clinicians to get their input on why they thought the intervention might be helpful, and any concerns they had about it. The input from the interviews and focus groups informed the intervention’s design, which we then feasibility-tested in 24 patients. In the interviews/focus groups, patients generally supported the idea of remotely reporting their symptoms and avoiding unnecessary visits; clinicians wanted to identify how the symptom reports would fit in their workflow. In the feasibility-test, only 10% of patients enrolled; in many cases, they were already having clinic visits less frequently or their clinicians did not feel comfortable seeing them less frequently. Among the 24 patient participants, the number of visits decreased (about 4 visits/patient vs. expected 6.5 visits/patient without the intervention). Patients generally supported the intervention. Clinicians felt that the symptom reports should be added to visits, rather than replacing them. Towards the end of the feasibility-test, the COVID-19 pandemic hit and led to an overall increase in telemedicine. Future research should explore how remote symptom reporting, telemedicine, and in-person visits can be combined to ensure that the right patients get the right care at the right time.

Introduction

The term PRO-cision Medicine, coined by Snyder, refers to personalizing care using patient-reported outcomes (PROs) [1]. Interest in routine PRO monitoring in advanced cancer patients has increased based on recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) findings [2,3,4]. For example, Basch et al. found that monitoring symptoms as an adjunct to routine visits improved health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL), increased ability to stay on chemotherapy, decreased emergency department admissions, and improved survival [2, 3]. These benefits were even greater in computer-inexperienced patients. Notably, the intervention tested by Basch et al. monitored symptoms, but was not used to tailor visit frequency. Systematic symptom reporting may be even more valuable when used to determine which patients need a visit when [1]. The RCT by Denis et al. used this approach in patients with advanced lung cancer, comparing follow-up based on weekly patient symptom reports to routine follow-up with CT scans every 3–6 months [4]. Their intervention produced improved survival, associated with better performance status at relapse, which enabled optimal treatment. Intervention patients were also more likely to have stable/improved HRQOL versus controls. Intervention patients had less imaging but more unscheduled visits versus control patients. Other studies also support the value of PRO symptom reporting [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Because of the US’ historically fee-for-service financing, medical care has generally been organized around visits. If there was no visit, there was no reimbursement. As the US transitions towards value-based reimbursement [15, 16], there are greater opportunities to use symptom monitoring not only as an adjunct to visits, but to monitor patients remotely to determine which patients need to be seen and which patients can avoid unneeded/unwanted visits. The surge in telemedicine associated with the COVID-19 pandemic has further expanded opportunities to tailor care delivery to patient’s needs [17].

We sought to develop a “PRO-cision Medicine” intervention in which remote symptom monitoring is used to tailor visit scheduling for metastatic breast and prostate cancer patients based on need. We selected the metastatic setting because of the long disease course during which patients undergo a series of treatments associated with a range of side effects, which may require additional supportive care [18, 19]. To ensure the PRO-cision Medicine intervention met the needs of patients and providers, we first conducted a qualitative study to obtain their input on the design of the intervention, which we then tested in a feasibility study.

Methods

The qualitative study and feasibility-test were approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Qualitative study

Study design

To inform the design of the PRO-cision Medicine intervention, we conducted cross-sectional, exploratory focus groups and one-on-one interviews with clinicians and patients. Because the intervention of using PRO symptom monitoring to tailor patients’ visits affects both patients and clinicians, it was important to get both groups’ perspectives at the design stage.

Participants

We recruited patients with metastatic breast and prostate cancer receiving care at three Johns Hopkins cancer center clinical sites, and the medical oncologists/nurse practitioners (NPs) involved in their care. Patients who were at least 21 years old, expected to live at least 6 months, and able to communicate in English were eligible. Medical oncologists/NPs/fellows who manage patients with metastatic breast or prostate cancer at a participating site were eligible. All participants underwent an IRB-approved oral consent process.

Focus group/interview conduct

Patient and clinician participants could attend one of several pre-scheduled, in-person focus groups or could schedule a one-on-one, in-person or phone interview. The target total sample size was 40: 15 metastatic breast cancer patients, 15 metastatic prostate cancer patients, and 10 medical oncologists/NPs. To obtain input from vulnerable populations, we purposively sampled patients such that at least 5 of the 15 in each tumor group were either a racial minority, did not graduate college, or reported “rare” or “never” computer use. The sample sizes were shaped by project resources and were intended to be exploratory and allow for adequate and diverse input from the three stakeholder groups.

Between November 2018 and March 2019 a facilitator with a long history of conducting qualitative interviews and focus groups with cancer patients and clinicians (SH) conducted the focus groups and interviews using a semi-structured guide appropriate for both focus groups and interviews, and for both patients and clinicians. Interview/focus group topics addressed key intervention characteristics: proposed symptom list, reporting frequency, patients’ comfort-level with technology, visit scheduling, and expectations regarding how symptom reports would be acted on (Table 1-Column 1). The focus groups/interviews were audio recorded and professionally transcribed.

Analysis

Transcripts were analyzed thematically to inform the PRO-cision Medicine intervention’s design [20]. An initial codebook was developed using the interview topics (Table 1-Column 1) to identify deductive codes. Using MAXQDA [21], SH initially coded five interviews, which were reviewed by CS; discrepancies in coding approach were discussed and reconciled. SH then deductively coded the remaining transcripts, with CS reviewing the coded transcripts to confirm coding agreement. Any remaining discrepancies in code application were resolved by discussion and consensus. After all interviews were coded, detailed reports were prepared for each parent code, which SH and CS reviewed to identify key themes for each topic. The two authors compared themes and developed a joint summary of the findings.

Feasibility-test

Study design

Informed by the qualitative interviews/focus groups, we conducted a single-arm, unblinded, feasibility-test of the PRO-cision Medicine intervention in patients with metastatic breast cancer. The study aimed to assess the feasibility of the PRO-cision Medicine intervention in practice and to obtain patients’ and clinicians’ perspectives regarding it. Given the study objectives and the funding available, it was considered preferable to test the intervention in as many patients as possible, rather than include a control arm.

Participants were recruited from the same clinical sites as the qualitative study and followed for 6-months. We tracked recruiting to achieve a purposive sample with at least 25% of patients representing racial minorities or having lower education (because electronic reporting was required, we did not purposively sample based on computer use).

Study participants

Recruitment occurred October–December 2019. Adult patients diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer with a life expectancy of at least 6 months who were undergoing treatment and who would normally have oncologist/NP visits at least monthly were eligible. While patients with prostate cancer were included in the qualitative study, we did not include them in the feasibility-test because they are commonly seen in clinic less frequently than monthly.

Patients had to be able and willing to report on symptoms via Epic® MyChart®. Patients enrolled in another clinical trial that influenced their visit schedule and/or health service use were not eligible. There was no target sample size; one of the outcome measures was the number of patients who enrolled during the pre-specified recruitment period, which was determined based on logistical considerations (i.e., study funding). Patients provided written informed consent.

The medical oncologists/NPs were asked to provide their perspectives on the intervention via an end-of-study interview. Because the clinicians were co-investigators, an IRB-approved waiver of consent document was included with the emailed interview invitation, and the interview script specified that completion of the interview represented consent.

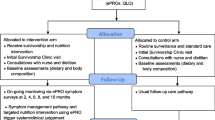

Intervention

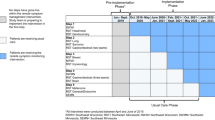

Figure 1 depicts the tested PRO-cision Medicine intervention versus usual care. We asked patients’ clinicians to estimate how many visits they would have during the 6-month study period under usual care and then scheduled them for half as many visits (e.g., patients who would have been seen monthly were scheduled for visits every other month). The frequency of laboratory tests and imaging studies were unchanged. Patients were asked to report on 17 symptoms: 14 items from the revised Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS-r) [22,23,24], plus three symptoms relevant to this patient population (hot flashes/flushes, vomiting, cough) and an option to add “other.” All symptoms were rated using the ESAS-r 11-point numeric rating scale from 0 = none to 10 = worst possible. This version of the ESAS-r has been used by the Michigan Oncology Quality Consortium to monitor patients taking oral oncolytics and was found to be feasible in both community and academic practices [22]. The specific symptoms were confirmed to be relevant for the feasibility-test during the qualitative study.

Depiction of feasibility-tested PRO-cision Medicine intervention vs. usual care. At the top, depiction of care delivery under usual care (if the patient had not been enrolled in the study). This example illustrates a patient who would have had in-person visits monthly. Between visits, if the patient had issues, the patient could have contacted the provider by phone call or MyChart message. There is no symptom monitoring. At the bottom, depiction of care delivery under the tested PRO-cision Medicine intervention. The patient is only pre-scheduled for half as many visits (every other month), is asked to complete symptom reports monthly, with the option to report symptoms in the intervening weeks. Clinicians’ offices can follow up on concerning scores by phone, MyChart message, or add a visit. Throughout, the patient may contact the provider by phone or MyChart message. There is no change to the schedule of laboratory testing and imaging studies (not depicted)

Clinicians ordered the questionnaires through the Epic electronic health record (EHR) questionnaire system, and patients completed the questionnaires via the MyChart patient portal. Patients were asked to complete the symptom reports monthly, with the option to complete the symptom reports during the intervening weeks. For the optional symptom reports, patients were first asked whether they had any new or bothersome symptoms that require attention and whether they would like to request an appointment. This was used because patients in the qualitative study reported that they did not want to respond to the same questions every week if nothing had changed. It also aimed to address the clinicians’ concerns regarding information overload. Finally, it ensured that patients who wanted to be seen in-person could be. If a patient requested an appointment, a member of the clinical team contacted the patient to schedule a visit. If a patient did not complete a weekly or monthly symptom report for 35 days, the clinical team called the patient.

Patients’ symptom questionnaire results were available to their clinician in Epic via the Synopsis View, InBasket, and the “Other Orders” folder in Chart Review. Alerts were generated for symptoms rated ≥ 4, representing moderate to severe symptoms [22,23,24]. Clinicians were asked to respond to alerts within three business days, consistent with other MyChart responses, and report to the research team how they responded (e.g., MyChart message, phone call, scheduled visit). Patients were directed to contact the clinic directly for urgent issues. Clinicians could use the information from the symptom reports (with or without alerts), along with laboratory results and imaging studies, to determine whether a patient should be seen for a visit sooner than the next scheduled visit, whether a phone consult or electronic message was needed, or whether the patient was stable.

Study conduct

At enrollment, we collected basic sociodemographic and clinical information from the patient’s clinician and medical record. At the end of the study, patients completed a survey [6, 7] and clinicians completed a semi-structured interview to ascertain what aspects of the intervention worked well or required refinement.

Outcomes and measures

Similar to previous studies [7], the primary outcomes assessed the feasibility of the PRO-cision Medicine intervention, including the percentage of eligible patients who enrolled, who completed the monthly symptom reports, who completed the optional weekly symptom reports, and frequency of alerts. From the clinician side, we evaluated timeliness and actions taken in response to alerts. Secondary outcomes included the number of medical oncologist/NP visits overall, and compared to the number of visits the clinicians reported each patient would have had in usual care. We also describe other health service use (e.g., phone calls, hospitalizations, urgent care visits).

Results

Qualitative study

Participant characteristics (Table 2)

We recruited the planned 15 breast and 15 prostate cancer patients (mean age 63.8 years, 80% White) and 10 clinicians. There was one clinician focus group (n = 8) and one patient focus group (n = 3); one-on-one interviews were conducted with the remaining participants. Twelve patients were a racial minority, had less than a college degree, and/or self-reported as computer inexperienced.

Key findings (Table 1-Column 2)

Participants noted the value of symptom reporting in alerting clinicians to emergent or bothersome issues, helping patients remember (and clinicians know) symptoms occurring between visits, and avoiding unneeded/unwanted visits. Some patients, however, did not see the benefits of avoiding visits, and clinicians were concerned about the workflow and time implications of reviewing the symptom reports and addressing issues.

Participants generally supported the appropriateness of the PRO-cision Medicine intervention for metastatic breast and prostate cancer patients. Respondents reported that the proposed list of symptoms for the assessment were appropriate and appreciated inclusion of both physical and mental aspects; however, many patients noted that they were not currently experiencing those issues. No symptoms were consistently identified as missing from the list; respondents supported the idea of including an “other (specify)” category. Recommendations for reporting frequency ranged from daily to quarterly, with several suggestions to report when symptoms are new or bothersome. While there was a general preference for completing the symptom reports electronically, there was no strong preference regarding mode (e.g., smartphone, computer). Respondents also recognized that some patients might be less comfortable with electronic reporting than others. While patients supported using remote symptom reporting to decrease in-person visit frequency, they did not want to forego all in-person visits. They preferred less frequent pre-scheduled appointments, with the option to add visits if needed. Clinicians noted that add-ons to their schedule are not uncommon, and that they could also discuss issues by phone.

Having clinicians address symptom reports with concerning issues within three days was considered consistent with other information reported through the MyChart patient portal. For urgent issues, patients should be instructed to contact the clinic by phone. Neither patients nor clinicians felt it was imperative for clinicians to review reports with no concerning issues. Participating patients felt comfortable being managed using technology, but noted other patients may not be. Clinicians reported concerns related to workflow, responsibility for reviewing/triaging the symptom reports, and the (non-billable) time required for the intervention. Because the focus groups and interviews occurred before the COVID-19 pandemic, there was little familiarity with telemedicine, but participants acknowledged that it could be a good option for some patients and that having video would be valuable, compared to audio-only phone consults.

Feasibility-study

Patient enrollment and characteristics (Table 2)

Of 236 patients screened, 24 (10%) enrolled. Of the 212 not enrolled, the most common reason was that the patients were already being seen less frequently than monthly (n = 97, 46%) or clinicians did not feel comfortable seeing the patients less frequently than monthly (n = 31; 15%). Other reasons for non-enrollment included participation in a conflicting clinical trial (n = 27), life expectancy less than 6 months (n = 9), and declined (n = 13). Recruitment of 35 patients was pending when recruitment closed.

Among the 24 enrolled patients, the mean age was 63 years, 75% were White, and 71% had completed post-graduate work. Clinically, 25% had been diagnosed with metastatic disease more than 5 years prior, and 54% were on their first or second line of therapy.

Two patients did not complete the 6-month follow-up (1 died, 1 transitioned to hospice). When COVID-19 restrictions to in-person care were instituted in March 2020, participants had, on average, 2 months left in the study (range 1.5–3 months).

Patterns of symptom reporting and clinician responses (Table 3)

A total of 335 optional weekly assessments were completed by 23 of the 24 enrolled patients (96%). Of 3 patients who requested an additional visit on their symptom assessment, 2 had a visit scheduled. Patients reported new or bothersome symptoms in 43 assessments (average 1.79/patient), 40 of which included moderate or severe symptoms (average 1.67/patient). The most commonly reported moderate or severe symptoms were tiredness (70% of alerts) and well-being (65%).

A total of 57 monthly symptom reports were completed by 17 of the 24 enrolled patients (71%), 2.38 assessments per enrolled patient, on average. One patient requested an additional visit, which was scheduled. There were 26 assessments that triggered alerts for moderate or severe symptoms (average 1.08/patient). The most commonly reported moderate or severe symptoms were well-being (53.9% of alerts), other (44.6%), tiredness (42.3%), and shortness of breath (42.3%).

There were 6 alerts for patients who did not complete either a weekly or monthly symptom assessment for longer than 35 days.

Patterns of health service use (Table 4)

Without the intervention the average expected number of visits to a medical oncologist/NP was 6.5; the average number of visits among the enrolled patients was about 4. The difference was statistically significant based on a post hoc paired t test (mean difference = 2.54; 95% CI 1.79–3.29; p < 0.0001). To account for COVID-19’s impact, we repeated the test and included the 14 video visits with the medical oncologist/NP: mean difference = 1.96; 95% CI 1.25–2.67, p < 0.0001. There were 206 phone calls, 73 with the medical oncologist/NP, including 36 in response to an alert. There were 134 MyChart messages, 100 with the medical oncologist/NP, including 4 in response to an alert. Two patients had urgent care visits, 4 patients had emergency department visits (1 patient 3 times), and 6 patients were hospitalized (1 patient twice). Two patients were sent to the emergency department based on symptom report alerts.

Patient end-of-study survey (Table 5)

Of the 24 enrolled patients, 19 completed the end-of-study survey. Support was high, with more than 80% agreeing with positive statements about the intervention. In open-ended comments, patients reported appreciating the opportunity to stay connected with their clinical team, though others reported having no symptoms or found completing the questionnaire a chore. In general, three days for the clinic to respond to concerning scores was considered appropriate for non-urgent issues; many patients heard back in one day while others reported delayed follow-up. One patient reported that the symptom survey identified significant issues she had thought were trivial. In terms of frequency for reporting, suggestions ranged from once monthly to twice monthly to weekly, with one participant suggesting that issues be reported when they happened. Almost all participants felt that they were seeing their oncologist/NP often enough, but one reported that the “survey did not take the place of an in-person visit” for someone who needs “to talk and ask questions.” Some patients liked using MyChart for communication, but others preferred visits or phone calls. Some patients experienced hassles trying to schedule appointments when needed. The list of symptoms was considered appropriate, with no other symptom consistently being raised in the comments.

Clinician end-of-study interviews (Table 6)

Of the 14 clinician co-investigators, 11 participated in an end-of-study interview (8 MDs, 3 NPs; 5/11 had directly recruited patients to the study, some MDs and NPs co-managed patients not directly recruited by themselves). The interviews occurred in July 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The clinicians thought the eligibility criteria were generally appropriate. However, in many cases, where clinicians felt comfortable seeing a patient less often than monthly, they were already doing so, thus limiting the eligible pool. Clinicians noted that they felt less comfortable decreasing visit frequency for patients whose disease is unstable, have high disease burden, are on active chemotherapy, are perceived as being anxious, or have a history of missed appointments. There were also concerns related to relying on symptom reporting to monitor patients (e.g., patients would not complete the questionnaire, questionnaire would not be sensitive enough). When asked which patients would be possible candidates for this intervention, beyond those with metastatic disease, clinicians mentioned other stable populations such as survivors of early-stage disease who are undergoing surveillance. However, many clinicians felt that the symptom monitoring should be added to clinic visits, rather than trying to replace them. The role of telemedicine in decreasing the need for in-person visits was raised, possibly in conjunction with symptom monitoring.

Clinicians found the questionnaire ordering process through the Epic EHR non-intuitive, and several reported that they either needed the research team to help them do it, or to do it for them. Clinicians also noted that the results, in the “Other Orders” folder in Chart Review or in Synopsis View, were not easy to find, and they preferred for the results to be directed to their InBasket. While in this study, the alerts were directed to the research team, who forwarded them to the appropriate clinicians, in the future, clinicians wanted the alerts directed to them or to clinic staff.

The clinicians generally endorsed the symptom questionnaire, including the content and the optional weekly reports and monthly assessment. One clinician suggested having the ability to tailor the questionnaire frequency depending on the patient. Recommended modifications included the ability to request a phone call or a visit (rather than just a visit), and alerts for incident symptoms (not chronic issues). There was also some interest in prioritizing alerts based on the symptom (e.g., “shortness of breath” could indicate an urgent issue requiring immediate notification and follow-up).

The clinicians found the alerts helped identify concerning issues and felt comfortable managing these issues remotely. They saw minimal value in reviewing the data for patients with no alerts. One clinician expressed concern that patients reported urgent issues that required immediate attention. There was some preference for phone management to avoid extensive back-and-forth via MyChart messages and because hearing the patient’s voice can be helpful. There were few instances when visits needed to be added, and these unscheduled visits could generally be accommodated without too much burden.

Discussion

PROs can play an important role as health care transitions to emphasize patient-centeredness and value rather than volume. We developed a PRO-cision Medicine remote symptom monitoring intervention to tailor visit frequency based on PROs, and feasibility-tested the intervention in metastatic breast cancer patients. We selected metastatic cancer given the success of previous studies in this population [2,3,4] and the long care trajectory with multiple treatments and side effects that can require supportive care.

While using remote symptom monitoring to decrease the frequency of in-person visits was largely endorsed by patients and clinicians in our qualitative study, the feasibility-test found that many clinicians were already decreasing visits for sufficiently stable patients such that 61% of approached patients were ineligible (46% already seen less than monthly; 15% clinicians uncomfortable seeing less often). Even though the PRO-cision Medicine intervention was effective in decreasing visits among the small fraction (10%) of patients who were enrolled (from an expected average of 6.5 visits to about 4 visits over the 6-month study period), decreasing visit frequency might not be the optimal endpoint for evaluating the benefits of the intervention.

Two patients were sent to the emergency department based on their symptom reports. This scenario is positive because it alerted clinicians to emergent issues, but also a concern because the issues required urgent attention, which is not the intention of the symptom monitoring system. While it is unlikely that a routinely scheduled visit would have caught the urgent symptoms, the patients may have been more likely to call the clinic in the absence of the symptom reporting. Notably, in multiple places the symptom reporting system urged patients not to report urgent issues via MyChart. It is possible that patients did not realize the urgency of their symptoms. Based on the experience of these two patients, we sent an email to all participating patients reminding them to contact their doctor’s office directly for issues requiring immediate attention and not to report urgent issues via the symptom report.

Several limitations of the feasibility-test are worth noting. Some patterns-of-care towards the end of the study may have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic; the repeated post hoc t test incorporating video visits may not fully account for the COVID-19 care delivery impacts. Further, we have no basis for comparing rates of phone calls, MyChart messages, hospitalizations, emergency department encounters, and urgent care visits. As described above, we used the limited study funds to test the intervention in as many patients as possible. While our sampling ensured representation from patients who identify as a minority race and/or with lower education in the qualitative study and feasibility-test, participation in the feasibility-test required willingness to report symptoms electronically, and over 70% of feasibility-test patients reported post-graduate education. From a health-system resource standpoint, it is helpful to achieve efficiencies in a subset of patients. However, it is important to continue to pursue opportunities to incorporate all interested patients in such interventions, particularly given evidence that symptom monitoring has even greater benefits in patients with less computer inexperience, lower education, and minority race [2, 6].

The disruptions in care delivery caused by the COVID-19 pandemic further emphasize the importance of delivering the right care to the right patient at the right time, not only for this study, but more generally. It has resulted in a substantial shift to telemedicine [17]. Given the low rates of eligibility for our feasibility-test, and the transformations in care related to COVID-19, further refinement and testing of the PRO-cision Medicine intervention will focus on in-person visits, telemedicine, and remote symptom monitoring, combined in a patient-centered way to ensure that the right patients get the right care at the right time.

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to participant privacy concerns and because of the protected health information collected.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Jensen, R. E., & Snyder, C. F. (2016). PRO-cision medicine: Personalizing patient care using patient-reported outcomes. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 34, 527–529. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.64.9491

Basch, E., Deal, A. M., Kris, M. G., Scher, H. I., Hudis, C. A., Sabbatini, P., Rogak, L., Bennett, A. V., Dueck, A. C., Atkinson, T. M., & Chou, J. F. (2016). Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 34, 557–565. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830

Basch, E., Deal, A. M., Dueck, A. C., Scher, H. I., Kris, M. G., Hudis, C., & Schrag, D. (2017). Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA, 318, 197–198. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7156

Denis, F., Lethrosne, C., Pourel, N., Molinier, O., Pointreau, Y., Domont, J., Bourgeois, H., Senellart, H., Trémolières, P., Lizée, T., & Bennouna, J. (2017). Randomized trial comparing a web-mediated follow-up with routine surveillance in lung cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 109, djx029. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djx029

Schougaard, L. M. V., Larsen, L. P., Jessen, A., Sidenius, P., Dorflinger, L., de Thurah, A., & Hjollund, N. H. (2016). AmbuFlex: Tele-patient-reported outcomes (telePRO) as the basis for follow-up in chronic and malignant diseases. Quality of Life Research, 25, 525–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1207-0

Snyder, C. F., Herman, J. M., White, S. M., Luber, B. S., Blackford, A. L., Carducci, M. A., & Wu, A. W. (2014). When using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice, the measure matters: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Oncology Practice, 10, e299-306. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2014.001413

Snyder, C. F., Blackford, A. L., Wolff, A. C., Carducci, M. A., Herman, J. M., Wu, A. W., & PatientViewpoint Scientific Advisory Board (2013). Feasibility and value of PatientViewpoint: A web system for patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice. Psycho-oncology, 22, 895−901. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3087

Snyder, C. F., & Aaronson, N. K. (2009). Use of patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice. The Lancet, 374, 369–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61400-8

Velikova, G., Booth, L., Smith, A. B., Brown, P. M., Lynch, P., Brown, J. M., & Selby, P. J. (2004). Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22, 714–724. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.06.078

Berry, D. L., Blumenstein, B. A., Halpenny, B., Wolpin, S., Fann, J. R., Austin-Seymour, M., Bush, N., Karras, B. T., Lober, W. B., & McCorkle, R. (2011). Enhancing patient-provider communication with the electronic self-report assessment for cancer: A randomized trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29, 1029–1035. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.30.3909

Santana, M.-J., Feeny, D., Johnson, J. A., McAlister, F. A., Kim, D., Weinkauf, J., & Lien, D. C. (2010). Assessing the use of health-related quality of life measures in the routine clinical care of lung-transplant patients. Quality of Life Research, 19, 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9599-3

Detmar, S. B., Muller, M. J., Schornagel, J. H., Wever, L. D., & Aaronson, N. K. (2002). Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communications. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 288, 3027–3034. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.23.3027

Cleeland, C. S., Wang, X. S., Shi, Q., Mendoza, T. R., Wright, S. L., Berry, M. D., Malveaux, D., Shah, P. K., Gning, I., Hofstetter, W. L., & Putnam, J. B., Jr. (2011). Automated symptom alerts reduce postoperative symptom severity after cancer surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29, 994–1000. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.29.8315

McLachlan, S. A., Allenby, A., Matthews, J., Wirth, A., Kissane, D., Bishop, M., Beresford, J., & Zalcberg, J. (2001). Randomized trial of coordinated psychosocial interventions based on patient self-assessment versus standard care to improve the psychosocial functioning of patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 19, 4117–4125. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2001.19.21.4117

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 et seq. (2010).

Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission. Global budgets. Retrieved from http://www.hscrc.state.md.us/Pages/budgets.aspx

Weiner, J. P., Bandeian, S., Hatef, E., Lans, D., Liu, A., & Lemke, K. W. (2021). In-person and telehealth ambulatory contacts and costs in a large US insured cohort before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 4, e212618. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.2618

American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts & figures 2017–2018: Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2017-2018.pdf.

American Cancer Society. Survival rates for prostate cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html.

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE Publications.

Mackler, E., Petersen, L., Severson, J., Blayney, D. W., Benitez, L. L., Early, C. R., Hough, S., & Griggs, J. J. (2017). Implementing a method for evaluating patient-reported outcomes associated with oral oncoloytic therapy. Journal of Oncology Practice, 13, e395–e400. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2016.018390

Hui, D., & Bruera, E. (2017). The Edmonton symptom assessment system 25 years later: Past, present, and future developments. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 53, 630–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.370

Michigan Oncology Quality Consortium. Retrieved from www.moqc.org.

Acknowledgements

We are immensely grateful to the patients and clinicians who participated in the qualitative interviews/focus groups and feasibility study. We also want to thank David Lim for assistance with early statistical analyses.

Funding

Supported by Cigarette Restitution Fund grants from the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins (P30CA006973).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Snyder has funding from Pfizer and Genentech through the institution and consults to Janssen via Health Outcomes Solutions. Ms. Thorner reports funding from Pfizer and Genentech. Dr. Stearns received research grants to institution from Abbvie, Biocept, Pfizer, Novartis, and Puma Biotechnology and is a Data Safety Monitoring Board member for Immunomedics, Inc. Dr. Karen Smith has received research funding through the institution from Pfizer and has a family member with stock in Abbott Laboratories and Abbvie. Dr. Katherine Smith, Dr. Hannum, Dr. Carducci, Ms. White, Ms. Blackford, Ms. Montanari, Ms. Ikejiani, and Mr. Smith report no conflicts or competing interests.

Ethical approval

These studies were reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

For the qualitative interviews, all participants underwent an IRB-approved oral consent process. For the feasibility study, patients provided written informed consent; the IRB waived documentation of consent for the clinician co-investigator end-of-study interviews. The waiver of consent document was included with the email invitation, and the interview script specified that completion of the interview represented consent to participate.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Snyder, C., Hannum, S.M., White, S. et al. A PRO-cision medicine intervention to personalize cancer care using patient-reported outcomes: intervention development and feasibility-testing. Qual Life Res 31, 2341–2355 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03093-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03093-3