Abstract

A primary community prevention approach in Iceland was associated with strong reductions of substance use in adolescents. Two years into the implementation of this prevention model in Chile, the aim of this study was to assess changes in the prevalence of adolescent alcohol and cannabis use and to discuss the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the substance use outcomes. In 2018, six municipalities in Greater Santiago, Chile, implemented the Icelandic prevention model, including structured assessments of prevalence and risk factors of substance use in tenth grade high school students every 2 years. The survey allows municipalities and schools to work on prevention with prevalence data from their own community. The survey was modified from an on-site paper format in 2018 to an on-line digital format in a shortened version in 2020. Comparisons between the cross-sectional surveys in the years 2018 and 2020 were performed with multilevel logistic regressions. Totally, 7538 participants were surveyed in 2018 and 5528 in 2020, nested in 125 schools from the six municipalities. Lifetime alcohol use decreased from 79.8% in 2018 to 70.0% in 2020 (X2 = 139.3, p < 0.01), past-month alcohol use decreased from 45.5 to 33.4% (X2 = 171.2, p < 0.01), and lifetime cannabis use decrease from 27.9 to 18.8% (X2 = 127.4, p < 0.01). Several risk factors improved between 2018 and 2020: staying out of home after 10 p.m. (X2 = 105.6, p < 0.01), alcohol use in friends (X2 = 31.8, p < 0.01), drunkenness in friends (X2 = 251.4, p < 0.01), and cannabis use in friends (X2 = 217.7, p < 0.01). However, other factors deteriorated in 2020: perceived parenting (X2 = 63.8, p < 0.01), depression and anxiety symptoms (X2 = 23.5, p < 0.01), and low parental rejection of alcohol use (X2 = 24.9, p < 0.01). The interaction between alcohol use in friends and year was significant for lifetime alcohol use (β = 0.29, p < 0.01) and past-month alcohol use (β = 0.24, p < 0.01), and the interaction between depression and anxiety symptoms and year was significant for lifetime alcohol use (β = 0.34, p < 0.01), past-month alcohol use (β = 0.33, p < 0.01), and lifetime cannabis use (β = 0.26, p = 0.016). The decrease of substance use prevalence in adolescents was attributable at least in part to a reduction of alcohol use in friends. This could be related to social distancing policies, curfews, and homeschooling during the pandemic in Chile that implied less physical interactions between adolescents. The increase of depression and anxiety symptoms may also be related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The factors rather attributable to the prevention intervention did not show substantial changes (i.e., sports activities, parenting, and extracurricular activities).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of substance use in adolescence is high, and the vulnerability to have negative consequences is increased (Jordan & Andersen, 2017; Levine et al., 2017; Spear, 2018). Typical behaviors of adolescents include novelty seeking, which increases the probability of drug use (Koob & Volkow, 2016; Volkow et al., 2016). The 1-year prevalence of cannabis use among secondary students in Chile reached a peak of 35% in 2015, and thereafter decreased to 27% (Libuy et al., 2020; Servicio Nacional para la Prevención y Rehabilitación del Consumo de Drogas y Alcohol, 2018), compared to 4.7% on average worldwide (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2020). More than a half of the secondary school students in Chile have used alcohol in the past year, and 30% in the past month (Servicio Nacional para la Prevención y Rehabilitación del Consumo de Drogas y Alcohol, 2018). In low- and middle-income countries, the prevalence of alcohol use during the past month among young adolescents is about 25% (Ma et al., 2018).

Substance use prevention addresses risk and protective factors on the levels of communities, families, friends, and of the individual (Chadi et al., 2018; Gruenewald et al., 2014; Harrop & Catalano, 2016; Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration’s Center for the Application of Prevention Technologies, 2017). The response of communities to substance use in adolescents and the reciprocal influence between adolescents, peers, and parents affect the progression of substance use over time (Guttmannova et al., 2019). Iceland has established a community prevention model of substance use in adolescents focused on the environment, culture, and the promotion of health in adolescents, informed by local risk and protective factors (Kristjansson et al., 2020a, b; Sigfúsdóttir et al., 2009). Evidence for the prevention model is still scarce in other countries (Kock et al., 2021; Koning et al., 2021). In Chile, six municipalities of the Metropolitan Region of Greater Santiago, the University of Chile, and the Icelandic Centre for Social Research and Analysis collaborated in the implementation and adaptation of the model since 2018 (Libuy et al., 2021). Municipalities are administrative units in Chile with local governments that may be larger than corresponding units in Iceland. The largest of the participating municipalities had more population than the entire Icelandic nation. The educational system in Chile includes public and private schools. Families with higher incomes can access and usually prefer private over public schools.

The COVID-19 pandemic and related lockdown policies have disrupted the lives and relationships between individuals, families, and entire communities, especially affecting the mental health of adolescents (Fegert et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). It has also affected the way, in which the mental health problems are addressed and prevented (Holmes et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2020). An increase of anxiety and depression symptoms has been described in adolescents (Racine et al., 2021), which can interact with substance use (Pelham et al., 2021). Social distancing can lead to a decrease of substance use in adolescents (Miech et al., 2021). Iceland has reported a decrease of alcohol use in adolescents during the pandemic (Thorisdottir et al., 2021), but several studies reported that in the USA, cannabis and alcohol use did not significantly change in this age group (Chaffee et al., 2021; Miech et al., 2021).

The aim of the present study was to assess changes in the prevalence of adolescent alcohol and cannabis use in Chile, 2 years into the implementation of a prevention model adapted from Iceland, and to discuss the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the substance use outcomes.

Methods

Design

We conducted two cross-sectional surveys in 2018 and in 2020, comprising multilevel data from municipalities, schools, and individuals. The research was carried-out in a naturalistic setting during a real process of prevention in action in six municipalities of the Metropolitan Region of Greater Santiago in Chile, initiated in 2018 with the implementation of a community-based prevention intervention of substance use in adolescents adapted from Iceland. The participation of the communities was by convenience. The six participating communities had local authorities or mayors willing to implement the prevention model and to fund the implementation using municipal budgets. The six municipalities were socially diverse, but not representative for the country. The score on the Social Priority Index ranged from 11.6 (no priority) to 75.8 (mid-high priority) (Contreras et al., 2022). The first survey in 2018 was applied at the beginning of the implementation process, and the second survey was applied 2 years into the implementation process of the model in 2020, in order to assess changes of substance use and risk factors in adolescents of the same municipalities.

Prevention Model

The prevention model includes a school-based survey of adolescents to inform and evaluate the community prevention work with local data. Each municipality designated a responsible individual within a prevention team. The University of Chile provided the technical support in monthly meetings with the delegates, adapted the strategies and recommendations for the municipalities, and assisted in the management and implementation of the prevention model.

Key components of this prevention model include (1) educating parents about the importance of emotional support, reasonable monitoring, and increasing the time they spend with their adolescent offspring; (2) encouraging young people to participate in organized recreational and extracurricular activities and sports; and (3) working with local schools in order to strengthen the supportive network between relevant agencies in the local community (Sigfusdottir et al., 2008).

The implementation of the Icelandic prevention model followed five guiding principles ( Kristjansson et al., 2020a): (1) apply a primary prevention approach that is designed to enhance the social environment; (2) emphasize community action and embrace public schools as the natural hub of neighborhood/area efforts to support child and adolescent health, learning, and life success; (3) engage and empower community members to make practical decisions using local, high-quality, accessible data, and diagnostics. (4) integrate researchers, policy makers, practitioners, and community members into a unified team dedicated to solving complex, real-world problems; and (5) match the scope of the solution to the scope of the problem, including emphasizing long-term intervention and efforts to marshal adequate community resources.

The prevention action did not offer structured or manualized programs, but guiding principles and recommendations. Therefore, the specific strategies and activities depended on each municipality and allowed for the integration of existing prevention programs. Common objectives were defined in the process and shared between the six municipalities that aimed at (1) reinforcing the administrative capacity and policies in the municipalities to conduct community prevention, (2) decreasing the access of adolescents to alcohol and other drugs, (3) increasing parental involvement and (4) decreasing the normalization among parents of adolescent alcohol and drug use, and (5) promoting environmental enrichment through organized extracurricular recreational activities.

A guide with ten steps to practical implementation of the Icelandic prevention model has been published (Kristjansson et al., 2020b). Even though the implementation process in Chile started before the publication of the ten steps, researchers from Chile and Iceland collaborated in the implementation process and the cited article may be based in part on the experience of Icelandic researchers to guide the implementation process in Chile.

The survey underwent a process of cultural and linguistic adaptation involving members of the municipal prevention teams, experts, and piloting among adolescents to ensure understanding, adequacy, and representation of relevant substances commonly used by adolescents in Chile. The survey applied to all tenth grade students is a key component of this community prevention model. It allows local timely feedback to municipalities and schools on substance use prevalence and risk factors in their community. Unlike the nationally representative surveys that are delivered many months or even more than a year after data collection in Chile, those surveys help to identify local needs and empower stake holders to work with their local data. The municipalities collaborated with teams from each school that were in charge of carrying out the application of the survey. The same teams were involved in the feedback of the local data. The entire process was planned and coordinated by the team from the University of Chile.

To assess the prevention activities on the level of the participating municipalities, we applied an adapted version of the Alcohol Prevention Magnitude Measure (Contreras et al., 2022). The prevention indices significantly increased among the participating municipalities between 2019 and 2020 (Contreras et al., 2022).

In line with the prevention model, the funding for implementing the surveys was provided by the local municipalities. Since the survey and local feedback of the survey data were inherent to the intervention, a non-controlled design of prevention in action was chosen. Later on, the central government started to implement the model at variable time points in more than 300 municipalities, albeit using federal funds, thus choosing a top down funding mechanism. Therefore, other municipalities would not have been adequate control conditions.

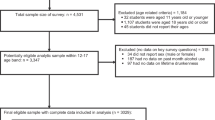

Participants

The participants of the surveys were tenth grade secondary students from schools nested in six urban municipalities of the Metropolitan Region of Santiago (Colina, Melipilla, Las Condes, Lo Barnechea, Peñalolen and Renca). The surveys were applied in June 2018 and in November 2020 to tenth grade students of the same schools and municipalities. In 2018, we used the original version of the survey translated and adapted from the Icelandic Model (Kristjansson et al., 2020a, b; Sigfúsdóttir et al., 2009), with a total of 360 items in paper and pencil format applied on-site. In 2020, the survey was shortened and questions about the pandemic were added with a total of 76 items. The survey was remotely delivered in an online format in 2020. The implementation was coordinated and supervised by the prevention teams of the municipalities with support and guidance of the Universidad de Chile, following the protocols developed by ICSRA (Kristjansson et al., 2013). All schools in the six municipalities were invited to participate. When schools accepted the participation, information was sent to the parents. A passive informed consent was sent to the parents, and an assent form was applied to the students. All students assented to participate before answering the survey.

COVID-19 Pandemic Chile

In March 2020, the state of emergency was called out in Chile due to the pandemic, and the government decreed a nationwide curfew to restrict the movement of people between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m. After 5 months, in August 2020, the starting time of the curfew was delayed to 11 p.m. and in November 2020 to 12 a.m.. The first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile was reached in June 2020. Since July 2020, a five-step plan has been implemented, which defined, based on epidemiological data at the municipal level, criteria for the opening or closing of dynamic lockdowns, maximum numbers for social meetings, and permissions to run on-site activities.

Municipalities underwent median lockdowns of 95 days (range from 59 to 151 days in the six municipalities) between March 2020 and the application of the second survey in November 2020. Five of the six municipalities eased the lockdown policies in the months of July or August 2020, and one municipality in October 2020. All municipalities had at least 1 month without complete lockdown, and the curfew was from 11 p.m. to 5 a.m. for all, when the second survey was applied. School activities comprised mainly online videoconferencing and homework, with better implementation in private schools than in public schools. The gradual return to classes on-site, once the municipalities had come out of the complete lockdown on step 1, depended on each school. Public schools had a slower return to on-site activities than private schools.

Variables and Outcomes

The outcomes selected in the present study were proportion of adolescents who report lifetime alcohol use, past-month alcohol use, lifetime drunkenness, past-month drunkenness, lifetime cannabis use, and frequent cannabis use.

The questions on cannabis use differed between the first and second survey. In both surveys, the item lifetime cannabis use was included in the same format. However, in 2018, participants stated how many times they had used cannabis, and in 2020, whether they had used cannabis in the past-month.

Independent variables selected from the survey were staying out after 10 p.m., perceived parenting, depression and anxiety symptoms, parental rejection of drunkenness, parental rejection of cannabis use, alcohol use in friends, drunkenness of friends, cannabis use in friends, no sports activity, and no organized extracurricular activity.

Covariates for adjusting the analyses were gender, age, living with both parents, employment status of the parents, school funding, and municipality.

Data Analysis

The socio-demographics and prevalence of alcohol and cannabis use were described by year. The proportion of students who used alcohol and cannabis were compared between 2018 and 2020 with chi-square tests for the outcomes with a confidence interval of 95%: lifetime alcohol use, past-month alcohol use, lifetime drunkenness, past-month drunkenness, and lifetime cannabis use. The proportion of students with the following risk factors were compared between 2018 and 2020 using chi-square tests with a confidence interval of 95%: staying out after 10 p.m., perceived parenting, depression and anxiety symptoms, lack of parental rejection of drunkenness, lack of parental rejection of cannabis use, alcohol use in friends, drunkenness of friends, cannabis use in friends, no sport activity, and no organized extracurricular activity.

Propensity score matching was conducted before the comparison of substance use outcomes between 2018 and 2020, and the comparison of the prevalence of risk factors between 2018 and 2020. The matching covariates were gender, age, living with both parents, employment status of the parents, and school funding. The ratio for matched cases in each group was 1. The matched sample sizes were 5376 students in 2018 and 2020. We used the nearest neighbor method (Randolph et al., 2014). The differences at baseline before and after the propensity score matching were not statistically significant.

The association between each risk factor and each outcome in 2018 and in 2020 was calculated by separate multilevel logistic regression models including all factors, adjusting for the covariates in order to control for potential confounders. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals, and are shown in forest plots.

The interaction between risk factors and year was calculated in adjusted multilevel logistic regressions for each outcome, in order to determine changes of the association between the risk factors and outcome of alcohol and cannabis use over the years. The data were nested in schools and municipalities, for which we accounted in the multilevel regression models. Intra-class correlations (ICC) were calculated in the null models of regressions for each outcome, to estimate the cluster effect at the level of schools and municipalities. The c-statistic was calculated in each full model in order to assess the discriminatory performance of the multilevel logistic regressions.

The analyses were performed with the software R version 4.0.4 for Windows. The package used for propensity score matching was MatchIt. The package used for multilevel analyses was lme4.

Ethics

The participation of the municipalities, schools, and students was voluntary. We used a passive informed consent procedure for the parents and an assent form for the students. The questionnaires were anonymous, protecting the identity of the students. The anonymized data were managed and stored by the research team. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Hospital Clínico Universidad de Chile (OAIC 981/18).

Results

Description of Sample

In 2018, n = 7538 tenth grade students, nested in 118 schools were surveyed in the schools. The response rate was 86.9%. In 2020, n = 5528 students from 100 schools participated in the online survey. The response rate was 72.8%. The two rounds of the survey were conducted in the same six municipalities of Greater Santiago. N = 93 schools were included in both rounds of the survey in the years 2018 and 2020; 25 schools only participated in 2018, and 7 schools only in 2020. Among the 125 participating schools, 95 were privately and 30 publicly funded. The mean age of students was 16 years, with a standard deviation (SD) of 0.66. In 2018, 48,7% of students were girls, and in 2020 51,9% were girls (Table 1).

Alcohol and Cannabis Use in Adolescents

The proportion of students who reported lifetime alcohol use decreased from 79.8% in 2018 to 70% in 2020 (X2 = 139.3, df = 1, p < 0.001). The prevalence of alcohol use in the past month decreased from 45.5% in 2018 to 33.4% in 2020 (X2 = 171.15, df = 1, p < 0.001). Lifetime drunkenness decreased from 42.2% in 2018 to 31.5% in 2020 (X2 = 130.0, df = 1, p < 0.001). Drunkenness in the past month decreased from 17.2% in 2018 to 12.8% in 2020 (X2 = 42.12, df = 1, p < 0.001). Lifetime cannabis use decreased from 27.9% in 2018 to 18.8% in 2020 (X2 = 127.4, df = 1, p < 0.001).

Regarding the indicator of regular use, 11.2% of the students reported in 2018 to have used cannabis ten or more times in their lifetime. In 2020, 6.9% reported to have used cannabis in the past-month. Table 2 shows the changes in prevalence of the substance use outcomes between 2018 and 2020.

Risk Factors of Substance Use

The proportion of students who reported staying out of house after 10:00 p.m. at least 1 day during the past week was 57.3% in 2018 and changed to 47.2% in 2020 (X2 = 105.58, df = 1, p < 0.001). The students who perceived low parenting were 26.6% in 2018 and 33.7% in 2020 (X2 = 63.82, df = 1, p < 0.001). The prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms increased from 31.1% in 2018 to 35.7% in 2020 (X2 = 23.52, df = 1, p < 0.001).

Low perceived parental rejection of drunkenness was 3.3% in 2018, and increased to 5.3% in 2020 (X2 = 24.87, df = 1, p < 0.001), while low parental rejection of cannabis use was 2.8% in 2018 and 2.7% in 2020 (X2 = 0.059, df = 1, p = 0.81).

Alcohol use in friends decreased from 51.4% in 2018 to 45.9% in 2020 (X2 = 31.80, df = 1, p < 0.001), drunkenness of friends also decreased from 33.1 to 19.7% (X2 = 251.43, df = 1, p < 0.001), and cannabis use in friends decreased from 22.2% to 11.6% (X2 = 217.69, df = 1, p < 0.001).

The proportion of students who did not practice sport activities decreased from 50.0% in 2018 to 30.8% in 2020 (X2 = 398.42, df = 1, p < 0.001), and the proportion of students who reported to not have participated in organized extracurricular activities also decreased from 70.9 to 57.8% (X2 = 195.33, df = 1, p < 0.001).

The changes in the prevalence of risk factors between 2018 and 2020 are shown in Fig. 1.

Association Between Risk Factors and Alcohol and Cannabis Use

In 2018, staying out of home after 10:00 p.m. was significantly associated with all substance use outcomes: lifetime alcohol use, past-month alcohol use, lifetime drunkenness, past-month drunkenness, lifetime cannabis use, and cannabis use 10 or more times in life. These associations were maintained in 2020. In 2018, low perceived parenting was also associated with all substance use outcomes; however, the association with past-month drunkenness was not significant in 2020. Alcohol use in friends was also significantly associated with all alcohol use outcomes in 2018 and 2020 and was associated with lifetime cannabis use. Cannabis use in friends was also associated with alcohol and cannabis use outcomes in both years. The association of cannabis use in friends with regular use of cannabis (cannabis use 10 or more times in life and past-month cannabis use) showed the highest AOR. In 2018, low parental rejection of drunkenness was significantly associated to past-month alcohol use, lifetime drunkenness, and past-month drunkenness with AOR over 2 and with lifetime cannabis use. In 2020, low parental rejection of drunkenness was associated to all substance use outcomes. However, AOR over 2 were only seen with alcohol use outcomes. Low parental rejection of cannabis use was associated with cannabis use outcomes in 2018 and 2020. The AOR were higher in 2020, and low parental rejection of cannabis use was also associated with past-month drunkenness in 2020.

Depression and anxiety symptoms were only associated with lifetime cannabis use in 2018. However, in 2020, depression and anxiety were associated with lifetime alcohol use, past-month alcohol use, lifetime drunkenness, lifetime cannabis use, and past-month cannabis use. To not practice sport activities in 2018 was associated with lower prevalence of lifetime alcohol use, lifetime drunkenness, and lifetime cannabis use, although with small effect sizes. In 2020, to not practice sport activities was not associated with any substance use outcome. To not participate in organized extracurricular activities was only associated to cannabis use 10 or more times in life in 2018. However, in 2020, this association was inverse, in both years with a small effect size. To not participate in organized extracurricular activities was not significantly associated with any other substance use outcome. Figure 2 shows the AOR as forest plots for all risk factors and each substance use outcome in 2018 and 2020.

Risk factors of adolescent substance use and their interaction with year (2018 and 2020). Odds ratios were adjusted for gender, age, living with both parents, employment status of the parents, school funding, and municipality. *Statistically significant interaction between factor and year, p < 0.05. For frequent cannabis use, the interaction between factor and year was not tested because questions leading to the outcome variable were differently phrased between the years 2018 and 2020, see the “Methods” section

The intra-class correlation coefficients for the alcohol use outcomes in 2018 ranged between 5.3 and 6.9% for the school level and from 0.7 to 3.0% for the level of the municipalities. The ICC of the cannabis use outcomes ranged from 15.2 to 24.8% for the school level, and from 1.3 to 2.2% for the level of the municipalities. In 2020, the ICC of the alcohol use outcomes ranged from 3.2 to 11.8% for the school level and from 0.9 to 4.4% for the level of the municipalities. The ICC of the cannabis use outcomes ranged from 13.5 to 14.8% for the level of schools and was < 0.1% for the level of the municipalities.

The c-statistic showed moderate to high values over 0.75 for all multilevel logistic regression models, indicating an adequate level of discrimination.

Interaction Between Year and Risk Factors

Depression and anxiety symptoms had a significantly stronger association in 2020 than in 2018 with several substance use outcomes in the adjusted multilevel logistic regression models: lifetime alcohol use (β = 0.34; p < 0.001), past-month alcohol use (β = 0.33; p < 0.001), lifetime drunkenness (β = 0.21; p = 0.02), and lifetime cannabis use (β = 0.26; p = 0.016). Alcohol use in friends had a significantly stronger association in 2020 than in 2018 with the outcomes lifetime alcohol use (β = 0.29; p = 0.006), past-month alcohol use (β = 0.24; p = 0.008), lifetime drunkenness (β = 0.35; p < 0.001), and past-month drunkenness (β = 0.48; p < 0.001). Low parental rejection of drunkenness had a significant interaction with year for lifetime alcohol use (β = 0.66; p = 0.042) with a stronger association in 2020 than in 2018. The interaction between low perceived parenting and year was significant for past-month drunkenness (β = − 0.25; p = 0.046). In all other risk factors, the year did not significantly interact with the outcomes in the adjusted multilevel logistic regression models.

Figure 2 shows the comparison of factors between years for each outcome.

Discussion

Between 2018 and 2020, the lifetime alcohol use, the past-month alcohol use, the lifetime drunkenness, the past-month drunkenness, and lifetime cannabis use decreased in adolescents of six municipalities in Greater Santiago. Several risk factors of substance use in adolescents also improved between 2018 and 2020, such as staying out of home after 10 p.m., alcohol use in friends, and cannabis use in friends. However, other factors pointed to an increased risk: perceived parenting, depression and anxiety symptoms, and low parental rejection of alcohol use. The reduction of alcohol use between 2018 and 2020 was related to the decrease of alcohol use in friends, whereas the increase in depression and anxiety symptoms was associated with higher odds for alcohol and cannabis use. The reduction of alcohol use in friends could be associated to social distancing policies, curfews, and homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile that implied less physical interactions between adolescents. The increase of depression and anxiety symptoms may also be related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The factors specifically targeted by the prevention model, such as sports activities, parenting, and extracurricular activities, did not show substantial changes of association with substance use between 2018 and 2020.

The Icelandic prevention model derives from important reductions of substance use reported for adolescents in Iceland in the past decades. Between 1997 and 2007, the prevalence of having been drunk in the past month decreased from 38 to 20% of the tenth grade students in Iceland; in the same period, daily tobacco use decreased from 21 to 10%, and lifetime cannabis use decreased from 13 to 7% (Sigfusdottir et al., 2008, 2009). The following protective and risk factors identified in Iceland were addressed in primary prevention: parents know who their children are with, parents know where their children are, parents know the friends of their children, parents know the parents of their children’s friends, participation in organized sports as protective factors, and party life-style as risk factor (Kristjansson et al., 2016).

The prevention model has been successful in reducing the prevalence of substance use in adolescents in Iceland. However, differences between trends for alcohol and cannabis use have been reported. The proportion of tenth grade students who had never used alcohol has increased, and the students who have used alcohol more than 40 times in life has decreased. However, the proportion of students who had never used cannabis in life has not increased, and the proportion of students who had used cannabis more than 40 times in life has slightly increased (Arnarsson et al., 2018). The model of prevention was criticized for the lack of clarity regarding the active components of the interventions, the lack of knowledge about mechanisms through which it is effective, and which behavioral outcomes in the young people are targeted. The scientific evidence supporting the model is still scarce, and the transfer to other settings is challenging because its implementation depends on the legal and social contexts in each country (Kock et al., 2021; Koning et al., 2021).

After reaching a peak in 2015, the prevalence of cannabis use in Chilean adolescents had slightly decreased in 2017. However, the prevalence rates of alcohol consumption had been stable in recent years (Libuy et al., 2020; Servicio Nacional para la Prevención y Rehabilitación del Consumo de Drogas y Alcohol, 2018). The decrease in substance use observed between 2018 and 2020 in this study was consistent for cannabis and alcohol in the municipalities where the prevention model was implemented. However, the findings may partly be explained by public health measures to control the pandemic, and not only by the prevention model.

How the COVID-19 pandemic affected the substance use in adolescents varies between contexts. Iceland reported a decline of cigarette smoking, e-cigarette use, and alcohol intoxication among adolescents of 15 to 18 years old from data obtained of a nationwide sample in 2016, 2018, and in October, 2020 (Thorisdottir et al., 2021).

In the USA, the prevalence rates did not significantly change for marijuana use in the past 30 days and for binge drinking in the past two weeks, in a longitudinal study of twelfth grade students surveyed at baseline in February and March 2020, 1 month before social distancing policies began, and at follow-up between July and August 2020 (Miech et al., 2021). However, perceived availability of marijuana, alcohol, and vaping devices declined during the pandemic (Miech et al., 2021). Similar results were reported for ninth- and tenth-grade students from California, where the use of tobacco, cannabis, and alcohol did not substantially differ before and after stay-at-home restrictions (Chaffee et al., 2021).

The decrease in alcohol use observed in the present study between 2018 and 2020 was related to less substance use in friends, which is an important factor in Chile. In a previous study, the importance of marijuana use in friends as a risk factor for adolescent marihuana use had been reported (Libuy et al., 2020). Less social interactions between adolescents may have led to a decrease in substance use or a delay in the initiation of substance use in adolescents.

Furthermore, the pandemic may have affected the mental health of adolescents. Increase in depression and anxiety symptoms were observed, and they were associated with a greater risk of substance use. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused substantial increase in the global prevalence and burden of major depression and anxiety disorders. Places with strongly decreased mobility and high infection rates had the greatest increase in prevalence of major depression and anxiety disorders (COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2021). Meta-analyses showed that 1 in 4 youths globally were experiencing clinically relevant depression symptoms, while 1 in 5 youths had clinically relevant anxiety symptoms, with higher prevalence rates in girls and older children (Racine et al., 2021).

In addition to the substance use in friends and depression and anxiety symptoms, other risk factors were found to be significantly associated with the use of alcohol and cannabis in adolescents: perceived parenting, low parental rejection of substance use, and staying out of house after 10:00 p.m. However, these risk factors did not interact with the year in their association with the substance use outcomes, remaining rather stable between 2018 and 2020. Surprisingly, sport activities and extracurricular activities were not strongly associated with adolescent alcohol and cannabis use, which could indicate a lack of supervision in those activities in Chile. It is a future challenge to transform sports and extracurricular activities into preventive activities, since they can even become risk factors, if they are not free of substance use (Murray et al., 2021). Adolescents in California had decreased the levels of physical activity during the pandemic (Chaffee et al., 2021), whereas an increase was reported in Chile. We hypothesize that less regular school activity led to more time in other activities as sports, although these sport activities may not have been formal, but self-guided and, therefore, not necessarily preventive for substance use.

In all, the absence of an association of parenting with the reduction of substance use between 2018 and 2020 and the absence of an inverse association of sports and extracurricular activities with substance use do not allow us to conclude that the prevention model contributed to reducing adolescent substance use.

The strengths of this study were the large participant population and the first implementation of the Icelandic prevention model in a metropolitan context of Latin America. The present research had also several limitations. The design was naturalistic, non-experimental, and non-controlled. In the context of strong environmental changes such as the pandemic, the reduction in adolescent substance use could not be directly attributed to the effectiveness of the prevention model. The data were self-reported. Furthermore, there were the limitations inherent to the Icelandic prevention model, with a lack of clarity about the active components of the model. Although the number of students participating in the surveys was high, the samples were not nationally representative or representative for all sectors of the municipalities.

In conclusion, the study showed a marked reduction of alcohol and cannabis use in adolescents in six municipalities of the Greater Metropolitan Region of Santiago in Chile, which have started to implement the Icelandic prevention model since 2018. However, these results can be influenced by measures to control the pandemic, and are not necessarily attributable to the effectiveness of the model. The implementation of the prevention model is an ongoing process, that in the future may need the transfer of further components. At the level of schools in Iceland, more structured work with parents is conducted by parental associations including parental agreements on hours of return to home and supervision of parties. The parental associations in each school promoting those agreements are coordinated at the municipal and national levels counting with full time professionals financed through the Ministry of Education in Iceland. Transferring those structures from small and homogeneous high-income contexts to diverse middle-income regions is challenging. Furthermore, sports and recreational activities need better supervision in Chile to serve as prevention components for adolescent substance use. Future research has to show whether the reductions of adolescent substance use observed in this study are sustainable over time after reopening of all school activities and after the return of normal peer interactions between adolescents.

Data Availability

Data will be made available by the corresponding author upon request without unduely restrictions.

References

Arnarsson, A., Kristofersson, G. K., & Bjarnason, T. (2018). Adolescent alcohol and cannabis use in Iceland 1995–2015. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37(November 2017), S49–S57. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12587

Chadi, N., Bagley, S. M., & Hadland, S. E. (2018). Addressing adolescents’ and young adults’ substance use disorders. Medical Clinics of North America, 102(4), 603–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.02.015

Chaffee, B. W., Cheng, J., Couch, E. T., Hoeft, K. S., & Halpern-Felsher, B. (2021). Adolescents’ substance use and physical activity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(7), 715–722. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0541

Contreras, L., Libuy, N., Guajardo, V., Ibáñez, C., Donoso, P., & Mundt, A. P. (2022). The alcohol prevention magnitude measure: Application of a Spanish-language version in Santiago, Chile. International Journal of Drug Policy, 107, 103793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103793

COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. 2021 Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet (London, England), 6736(21):1–13 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L., & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3

Gruenewald, P. J., Remer, L. G., & LaScala, E. A. (2014). Testing a social ecological model of alcohol use: The California 50-city study. Addiction, 109(5), 736–745. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12438

Guttmannova, K., Skinner, M. L., Oesterle, S., White, H. R., Catalano, R. F., & Hawkins, J. D. (2019). The interplay between marijuana-specific risk factors and marijuana use over the course of adolescence. Prevention Science, 20(2), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0882-9

Harrop, E., & Catalano, R. F. (2016). Evidence-based prevention for adolescent substance use. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25(3), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2016.03.001

Holmes, E. A., O’Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., Ballard, C., Christensen, H., Cohen Silver, R., Everall, I., Ford, T., John, A., Kabir, T., King, K., Madan, I., Michie, S., Przybylski, A. K., Shafran, R., Sweeney, A., … & Bullmore, E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

Jordan, C. J., & Andersen, S. L. (2017). Sensitive periods of substance abuse: Early risk for the transition to dependence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 25, 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2016.10.004

Kock, D., Kreeft, V. Der., & Icelandic, G. T. (2021). The Icelandic Model: Is the hype justified? Position paper of the European Society for Prevention Research on the Icelandic model The Icelandic model; is the hype justified? 2020.

Koning, I. M., De Kock, C., van der Kreeft, P., Percy, A., Sanchez, Z. M., & Burkhart, G. (2021). Implementation of the Icelandic prevention model: A critical discussion of its worldwide transferability. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 28(4), 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2020.1863916

Koob, G. F., & Volkow, N. D. (2016). Neurobiology of addiction: A neurocircuitry analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(8), 760–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00104-8

Kristjansson, A. L., Mann, M. J., Sigfusson, J., Thorisdottir, I. E., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2020a). Development and Guiding Principles of the Icelandic Model for Preventing Adolescent Substance Use. Health Promotion Practice, 21(1), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919849032

Kristjansson, A. L., Mann, M. J., Sigfusson, J., Thorisdottir, I. E., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2020b). Implementing the Icelandic model for preventing adolescent substance use. Health Promotion Practice, 21(1), 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919849033

Kristjansson, A. L., Sigfusdottir, I. D., Thorlindsson, T., Mann, M. J., Sigfusson, J., & Allegrante, J. P. (2016). Population trends in smoking, alcohol use and primary prevention variables among adolescents in Iceland, 1997–2014. Addiction, 111(4), 645–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13248

Kristjansson, A. L., Sigfusson, J., Sigfusdottir, I. D., & Allegrante, J. P. (2013). Data collection procedures for school-based surveys among adolescents: The youth in europe study. Journal of School Health, 83(9), 662–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12079

Levine, A., Clemenza, K., Rynn, M., & Lieberman, J. (2017). Evidence for the risks and consequences of adolescent Cannabis exposure. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(3), 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.12.014

Libuy, N., Ibáñez, C., Guajardo, V., Araneda, A. M., Contreras, L., Donoso, P., & Mundt, A. P. (2021). Adaptación e implementación del modelo de prevención de consumo de sustancias Planet Youth en Chile. Revista Chilena De Neuro-Psiquiatría, 59(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0717-92272021000100038

Libuy, N., Ibáñez, C., & Mundt, A. P. (2020). Factors related to an increase of cannabis use among adolescents in Chile: National school based surveys between 2003 and 2017. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 11(October 2019), 100260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100260

Ma, C., Bovet, P., Yang, L., Zhao, M., Liang, Y., & Xi, B. (2018). Alcohol use among young adolescents in low-income and middle-income countries: A population-based study. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, 2(6), 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30112-3

Miech, R., Patrick, M. E., Keyes, K., O’Malley, P. M., & Johnston, L. (2021). Adolescent drug use before and during U.S. national COVID-19 social distancing policies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 226(May), 108822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108822

Murray, R. M., Sabiston, C. M., Doré, I., Bélanger, M., & O’Loughlin, J. L. (2021). Longitudinal associations between team sport participation and substance use in adolescents and young adults. Addictive Behaviors, 116(December 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106798

Pelham, W. E., Tapert, S. F., Gonzalez, M. R., McCabe, C. J., Lisdahl, K. M., Alzueta, E., Baker, F. C., Breslin, F. J., Dick, A. S., Dowling, G. J., Guillaume, M., Hoffman, E. A., Marshall, A. T., McCandliss, B. D., Sheth, C. S., Sowell, E. R., Thompson, W. K., Van Rinsveld, A. M., Wade, N. E., & Brown, S. A. (2021). Early adolescent substance use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal survey in the ABCD study cohort. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 69(3), 390–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.06.015

Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., Kontopantelis, E., Webb, R., Wessely, S., McManus, S., & Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

Randolph, J. J., Falbe, K., Manuel, A. K., & Balloun, J. L. (2014). A step-by-step guide to propensity score matching in R. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 19(18), 1–6.

Servicio Nacional para la Prevención y Rehabilitación del Consumo de Drogas y Alcohol. (2018). Décimo Segundo Estudio Nacional de Drogas en Población Escolar de Chile, 2017 8° Básico a 4° Medio. In SENDA Ministerio del Interior y Seguridad Pública Gobierno de Chile.

Shi, L., Lu, Z.-A., Que, J.-Y., Huang, X.-L., Liu, L., Ran, M.-S., Gong, Y.-M., Yuan, K., Yan, W., Sun, Y.-K., Shi, J., Bao, Y.-P., & Lu, L. (2020). Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 3(7), e2014053. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053

Sigfusdottir, I. D., Kristjansson, A. L., Thorlindsson, T., & Allegrante, J. P. (2008). Trends in prevalence of substance use among Icelandic adolescents, 1995–2006. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 3, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-3-12

Sigfúsdóttir, I. D., Thorlindsson, T., Kristjánsson, Á. L., Roe, K. M., & Allegrante, J. P. (2009). Substance use prevention for adolescents: The Icelandic Model. Health Promotion International, 24(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dan038

Spear, L. P. (2018). Effects of adolescent alcohol consumption on the brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 19(4), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2018.10

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Center for the Application of Prevention Technologies. (2017). Preventing Youth Marijuana Use: Factors Associated with Use; Decision-Support Tools, updated October, 2017.

Thorisdottir, I. E., Asgeirsdottir, B. B., Kristjansson, A. L., Valdimarsdottir, H. B., Jonsdottir Tolgyes, E. M., Sigfusson, J., Allegrante, J. P., Sigfusdottir, I. D., & Halldorsdottir, T. (2021). Depressive symptoms, mental wellbeing, and substance use among adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iceland: A longitudinal, population-based study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(8), 663–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00156-5

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2020). Booklet 2: Drug use and health consequences. In World Drug Report.

Volkow, N. D., Koob, G. F., & McLellan, A. T. (2016). Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(4), 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1511480

Funding

The study received funding by the grant scheme FONIS, grant number SA19I0152, Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID), Chile; NL received the grant PFCHA/Doctorado Nacional/2018- 201180520, ANID.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical of Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico Universidad de Chile (Nono. OAIC 981/18).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Libuy, N., Ibáñez, C., Araneda, A.M. et al. Community-Based Prevention of Substance Use in Adolescents: Outcomes Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Santiago, Chile. Prev Sci 25, 245–255 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01539-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01539-9