Abstract

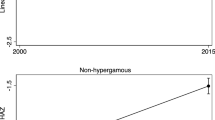

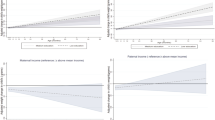

This study explores the relationship between parental educational similarity—educational concordance (homogamy) or discordance (heterogamy)—and children’s health outcomes. Its contribution is threefold. First and foremost, I use longitudinal data on children’s health outcomes tracking children from age 1 to 15, thus being able to assess whether the relationship changes at key life-course and developmental stages of children. This is an important addition to the relevant literature, where the focus is solely on outcomes at birth. Second, I look at different health outcomes, namely height-for-age (HFA) and BMI-for-age (BFA) z-scores, alongside their dichotomized counterparts, stunting and thinness. Third, I conduct the same set of analyses in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam, thus providing multi-context evidence from countries at different levels of development and with different socio-economic characteristics and gender dynamics. Results reveal important heterogeneity across contexts. In Ethiopia and India, parental educational homogamy is associated with worse health outcomes in infancy and childhood, while associations are positive in Peru and, foremost, Vietnam. Complementary estimates from matching techniques show that these associations tend to fade after age 1, except in Vietnam, where the positive relationship persists through adolescence, thus supporting the homogamy-benefit hypothesis not only at birth, but also across the early life course. Insights from this study contribute to the inequality debate on the intergenerational transmission of advantage and disadvantage and shed additional light on the relationship between early-life conditions and later-life outcomes in critical periods of children’s lives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Parental educational similarity and parental educational homogamy are synonyms. Conversely, educational hypogamy refers to a situation in which the female partner has higher education than the male partner, while educational hypergamy refers to a situation in which the male partner has higher education than the female partner.

Although it is not possible to distinguish between, for instance, labor migration and family instability, a decrease in the percentage of children living in the same household with both parents over their life course is observed in all four countries. For instance, conditional on both parents being alive at the time of the survey, in Ethiopia 69 percent of children live with both parents at age 8, 61 percent at age 12, and 55 percent at age 15. The same estimates are 90, 80, and 75 percent in India; 73, 66, and 59 percent in Peru; and 88, 78, and 71 percent in Vietnam.

Educationally heterogamous couples can be hypogamous if the difference is negative or hypergamous if the difference is positive.

For additional details, Online Figure A1 in Reynolds et al. (2017) is also insightful as it illustrates the distribution of parental schooling pairs showing the schooling levels that are coded with integer values 0–9.

Only younger siblings are considered here because I include birth order—another way of measuring the number of older siblings—as another control.

For robustness checks reported in the Online Appendix (except for Table A3), only two specifications per outcome are reported, namely NC (no controls) and FULL (all set of controls included).

Note that the number of children with mothers with upper secondary or tertiary education is very low in Ethiopia and India (less than 5 percent of the sample), thus by construction limiting the absolute number of educationally homogamous couple pairings at the top of the distribution (the ones in the graph are proportions).

The discrepancies highlighted here are in line with previous findings and comparisons that were made between the YL survey and nationally representative statistics. The Ethiopian sample was compared with the 2000 DHS and the 2000 Welfare Monitoring Survey. The analyses showed that households in the Young Lives sample were slightly better off and had better access to basic services than the average household in Ethiopia. The Indian sample was compared with the 1998/9 DHS. The analysis showed that households in the Young Lives sample were slightly wealthier than households in the DHS sample. The Vietnam sample was compared with the 2002 DHS and the 2002 Vietnam Household Living Standard Survey. The analysis showed that households in the Young Lives sample were slightly poorer than the households in the other samples. The Peru sample was compared with the 2000 DHS, the 2001 Peru Living Standard Measurement Survey (LSMS), and the 2005 National Census. The analysis showed that the poverty rates of the Young Lives sample were similar to the urban and rural averages derived from the LSMS, and slightly wealthier than households in the DHS.

References

Abufhele, A., Castro, A. F., & Pesando, L. M. (2020). Parental educational similarity and infant health in Chile: Evidence from administrative records: 1990–2015. Working Paper (manuscript currently revised and resubmitted).

Aizer, A., Stroud, L., & Buka, S. (2016). Maternal stress and child outcomes: Evidence from siblings. Journal of Human Resources, 51(3), 523–555.

Anand, P., Behrman, J. R., Dang, H. A. H., & Jones, S. (2018). Varied patterns of catch-up in child growth: Evidence from Young Lives. Social Science and Medicine, 214(July), 206–213.

Barnett, I., Ariana, P., Petrou, S., Penny, M. E., Duc, L. T., Galab, S., & Boyden, J. (2013). Cohort profile: The young lives study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(3), 701–708.

Beck, A., & González-Sancho, C. (2009). Educational assortative mating and children’s school readiness. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing Working Paper.

Becker, G. S. (1981). A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Behrman, J. A. (2020). Mother’s relative educational status and early childhood height-for-age z scores: A decomposition of change over time. Population Research and Policy Review, 39, 147–173.

Beijers, R., Jansen, J., Riksen-Walraven, M., & De Weerth, C. (2010). Maternal prenatal anxiety and stress predict infant illnesses and health complaints. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3226.

Bratsberg, B., Markussen, S., Raaum, O., Røed, K., & Røgeberg, O. (2018). Trends in assortative mating and offspring outcomes. IZA Discussion Paper Series, (11753).

Breen, R., & Salazar, L. (2011). Educational assortative mating and earnings inequality in the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 117(3), 808–843.

Briones, K. (2018). A guide to Young Lives rounds 1 to 5 constructed files. Young Lives Technical Note, 48, 1–31.

Case, A., & Paxson, C. (2010). Causes and consequences of early-life health. Demography, 47, 65–85.

Casterline, J. B., Williams, L., & McDonald, P. (1986). The age difference between spouses: Variations among developing countries. Population Studies, 40(3), 353–374.

Cole, T. J., Flegal, K. M., Nicholls, D., & Jackson, A. A. (2007). Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: International survey. British Medical Journal, 335(7612), 194–197.

Cools, S., & Kotsadam, A. (2017). Resources and intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 95, 211–230.

Corno, L., Hildebrandt, N., & Voena, A. (2020). Age of marriage, weather shocks, and the direction of marriage payments. Econometrica, 88(3), 879–915.

Dancause, K. N., Laplante, D. P., Oremus, C., Fraser, S., Brunet, A., & King, S. (2011). Disaster-related prenatal maternal stress influences birth outcomes: Project Ice Storm. Early Human Development, 87(12), 813–820.

De Hauw, Y., Grow, A., & Van Bavel, J. (2017). The reversed gender gap in education and assortative mating in Europe. European Journal of Population. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-016-9407-z.

De Onis, M., & Branca, F. (2016). Childhood stunting: A global perspective. Maternal and Child Nutrition, 12, 12–26.

De Onis, M., Onyango, A. W., Borghi, E., Siyam, A., Nishida, C., & Siekmann, J. (2007). Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 85(9), 660–667.

Eika, L., Mogstad, M., & Zafar, B. (2019). Educational assortative mating and household income inequality. Journal of Political Economy, 127(6), 000–000.

Esteve, A., Garcia, J., & Permanyer, I. (2012). The reversal of the gender gap in education and its impact on union formation: the end of hypergamy. Population and Development Review, 38(3), 535–546.

Esteve, A., Schwartz, C. R., Bavel, J. V., Permanyer, I., Klesment, M., & Garcia, J. (2016). The End of Hypergamy: Global Trends and Implications. Population and Development Review, 42(4), 615–625.

Furlong, K. R., Anderson, L. N., Kang, H., Lebovic, G., Parkin, P. C., Maguire, J. L., & Birken, C. S. (2016). BMI-for-Age and weight-for-length in children 0 to 2 years. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3809.

Furstenberg, F. F. (2005). Banking on families: How families generate and distribute social capital. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 809–821.

Ganguli, I., Hausmann, R., & Viarengo, M. (2014). Closing the gender gap in education: What is the state of gaps in labour force participation for women, wives and mothers? International Labor Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1564-913X.2014.00007.x.

Garfinkel, I., Glei, D. A., & McLanahan, S. (2002). Assortative mating among unmarried parents. Journal of Population Economics, 15, 417–432.

Georgiadis, A., Benny, L., Duc, L. T., Galab, S., Reddy, P., & Woldehanna, T. (2017). Growth recovery and faltering though early adolescence in low- and middle-income countries: Determinants and implications for cognitive development. Social Science and Medicine, 179, 81–90.

Goldstein, J. R., & Harknett, K. (2006). Parenting across racial and class lines: Assortative mating patterns of new parents who are married, cohabiting, dating or no longer romantically involved. Social Forces, 85(1), 121–143.

Greenwood, J., Guner, N., Kocharkov, G., & Santos, C. (2014). Marry your like: Assortative mating and income inequality. American Economic Review, 104(5), 348–353.

Gullickson, A., & Torche, F. (2014). Patterns of racial and educational assortative mating in Brazil. Demography, 51(3), 835–856.

Gutman, L. M., McLoyd, V. C., & Tokoyawa, T. (2005). Financial strain, neighborhood stress, parenting behaviors, and adolescent adjustment in urban African American families. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15(4), 425–449.

Haushofer, J., & Fehr, E. (2014). On the psychology of poverty. Science, 344(6186), 862–867.

Headey, D., Hoddinott, J., Ali, D., Tesfaye, R., & Dereje, M. (2015). The other Asian enigma: Explaining the rapid reduction of undernutrition in Bangladesh. World Development, 66, 749–761.

Kerr, M. E. (2000). One’s Family Story: A Primer on Bowen Theory. Washington, DC: The Bowen Center for the Study of the Family.

Kumar, A., & Singh, A. (2013). Decomposing the gap in childhood undernutrition between poor and non-poor in urban India, 2005–06. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064972.

Young Lives. (2017). A Guide to Young Lives Research. (May), 1–46. Retrieved from www.younglives.org.uk

Lopus, S., & Frye, M. (2020). Intramarital status differences across Africa’s educational expansion. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(2), 733–750.

Mare, R. D. (2016). Educational homogamy in two gilded ages: Evidence from inter-generational social mobility data. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 663(1), 117–139.

Martin, A., Ryan, R. M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2007). The joint influence of mother and father parenting on child cognitive outcomes at age 5. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(4), 423–439.

Minuchin, P. (1985). Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development, 56(2), 289–302.

Nievar, M. A., & Luster, T. (2006). Developmental processes in African American families: An application of McLoyd’s theoretical model. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(2), 320–331.

Persson, P., & Rossin-Slater, M. (2018). Family ruptures, stress, and the mental health of the next generation. American Economic Review, 108(4–5), 1214–11252.

Pesando, L. M. (2021). Educational assortative mating in sub-Saharan Africa: Compositional changes and implications for household wealth inequality. Demography (forthcoming).

Pesando, L. M., & Abufhele, A. (2019). Household determinants of teen marriage: Sister effects across four low- and middle-income countries. Studies in Family Planning, 50(2), 113–136.

Petrou, S., & Kupek, E. (2010). Poverty and childhood undernutrition in developing countries: A multi-national cohort study. Social Science and Medicine, 71(7), 1366–1373.

Popkin, B. M., Corvalan, C., & Grummer-Strawn, L. M. (2020). Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet, 395(10217), 65–74.

Psaki, S. R., McCarthy, K. J., & Mensch, B. S. (2018). Measuring Gender Equality in Education: Lessons from Trends in 43 Countries. Population and Development Review, 44(1), 117–142.

Rauscher, E. (2020). Why who marries whom matters: Effects of educational assortative mating on infant health in the United States 1969–1994. Social Forces, 98(3), 1143–1173.

Reynolds, S. A., Andersen, C., Behrman, J., Singh, A., Stein, A. D., Benny, L., & Fernald, L. C. H. (2017). Disparities in children’s vocabulary and height in relation to household wealth and parental schooling: A longitudinal study in four low- and middle-income countries. SSM - Population Health, 3(February), 767–786.

Rosenfeld, M. J. (2008). Racial, educational and religious endogamy in the United States: A comparative historical perspective. Social Forces, 87(1), 1–31.

Schott, W. B., Crookston, B. T., Lundeen, E. A., Stein, A. D., & Behrman, J. R. (2013). Periods of child growth up to age 8 years in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam: Key distal household and community factors. Social Science and Medicine, 97, 278–287.

Schwartz, C. R. (2013). Trends and variation in assortative mating: Causes and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 39(1), 451–470.

Schwartz, C. R., & Mare, R. D. (2005). Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography, 42(4), 621–646.

Seckl, J. R. (1998). Physiologic programming of the fetus. Clinics in Perinatology, 25(4), 939–964.

Smits, J., & Park, H. (2009). Five decades of educational assortative mating in 10 East Asian societies. Social Forces, 88(1), 227–255.

Torche, F. (2010). Educational assortative mating and economic inequality: A comparative analysis of three latin American countries. Demography, 47(2), 481–502.

Torche, F. (2011). The effect of maternal stress on birth outcomes: Exploiting a natural experiment. Demography, 48(4), 1473–1491.

Torche, F., & Kleinhaus, K. (2012). Prenatal stress, gestational age and secondary sex ratio: The sex-specific effects of exposure to a natural disaster in early pregnancy. Human Reproduction, 27(2), 558–567.

Wilson, I., & Huttly, S. (2004). Young Lives: A case study of sample design for longitudinal research. Young Lives Working Paper N. 10, 1–16.

World Health Organization. (2006). WHO child growth standards: Methods and development. EN Technical Report, 1–336.

Zhang, H., Ho, P. S. Y., & Yip, P. S. F. (2012). Does similarity breed marital and sexual satisfaction? Journal of Sex Research, 49(6), 583–593.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges financial support for this paper through the Faculty of Arts at McGill University and through the Global Family Change (GFC) Project (http://web.sas.upenn.edu/gfc), a collaboration between the University of Pennsylvania, University of Oxford (Nuffield College), Bocconi University, and the Centro de Estudios Demogràficos (CED) at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Funding for the GFC Project is provided through NSF Grant No. 1729185 (PIs: Kohler & Furstenberg), ERC Grant 694262 (PI: Billari), ERC Grant 681546 (PI: Monden), the Population Studies Center and the University Foundation at the University of Pennsylvania, and the John Fell Fund and Nuffield College at the University of Oxford. The author also wishes to thank the Editor and two anonymous referees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pesando, L.M. A Four-Country Study on the Relationship Between Parental Educational Homogamy and Children’s Health from Infancy to Adolescence. Popul Res Policy Rev 41, 251–284 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-020-09627-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-020-09627-2