Abstract

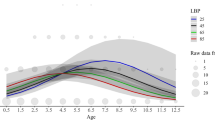

This paper employs a cohort analysis to examine the recent decline in the number of deer hunters in the State of Wisconsin and considers the implications of hunter decline for wildlife management and conservation. North American natural resource management strategies currently depend on hunters and anglers to fund habitat conservation, wildlife management, and land protection through license fees and special taxes on hunting equipment. However, hunter participation is declining across the United States, challenging the long-term viability of this approach. We undertake an age-period-cohort (APC) approach to analyze hunter participation rates and introduce an APC method to project the future number of hunters in Wisconsin. We find that if the recent patterns continue, the number of Wisconsin male deer hunters will decline by more than 10 % (55,304 hunters) in the next 10 years and an additional 18 % (88,552 hunters) between 2020 and 2030.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Author’s calculations from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Hunting License Reports divided by total population count reported by U.S. Census Bureau.

Hunting for big game, such as deer, has only recently begun to decline somewhat at the national level. Declines in the number of small game and migratory bird hunters have been much more stark (Mockrin et al., under review).

In reviewing historical license records for the past 15 years, only 10 % of Wisconsin hunters do not hunt deer with a firearm.

We conducted a detailed demographic analysis of female deer hunters in Wisconsin in 2008.

There were no changes in license prices or tag number during this study period, and there are no lotteries for deer tags.

It is important to note that we only have ten years of data and that short time period introduces limitations to this study making it particularly difficult to distinguish between age and cohort effects. This limitation is discussed in more detail under conclusions and implications, but is important to keep in mind while reading and interpreting our results.

CWD is a contagious degenerative disease found in deer and elk that is transferred from animal to animal through close contact. It is prevalent in several states across the Western and Midwestern United States. It was discovered in the wild Wisconsin herd in early fall 2002, before the start of the hunting season. The 2002 hunting season saw a significant drop in hunter numbers due to CWD concerns (Vaske et al. 2004). Since 2002, hunters have gained more information, the media hype about the disease has largely subsided, and hunter numbers rebounded in 2003 and 2004. We expect that CWD would cause a period effect in 2002, with lower likelihoods to hunt in that year and potentially in the years immediately following.

It is difficult to interpret results for those born prior to 1935 because they were already over age 65 in 2000 at the start of our data collection and may have been influenced as much by age as by cohort.

Assumptions about future period effects play a large role in the outcome of the projection model. If we made an alternative projection assuming that period effects observed in 2009 would remain constant in the future, the projected number of hunters would indicate a moderate increase (rather than decline) over the observed 2009 hunter numbers.

While FHWAR data offer a significantly longer time series, they are not suitable at the state level for the detailed APC analysis we have conducted here because they rely on self-reported behavior, they are not available on an annual basis, and because the sample size at the state level is relatively small. The license data we have chosen to use instead provide a complete annual count of all hunters by single year of age and sex for the last ten years and allow us to identify very recent changes in hunter participation rates.

Wisconsin is a special case in which deer hunting remains an extraordinarily popular activity. Predicted hunter decline in this context may foreshadow more dire circumstances in other states, or other states that experienced more profound hunter decline in earlier time periods may have already experienced the bulk of decline and may begin to experience more stable hunter populations. National-level studies and/or comparative studies analyzing multiple states will be important in better understanding broader trends and their implications.

References

Aiken, R. (2010). Trends in fishing and hunting 1991–2006: A focus on fishing and hunting by species. Report 2006-8. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Benson, D. E. (2001). Survey of state programs for habitat, hunting, and nongame management on private lands in the United States. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 29(1), 354–358.

Coombes, B. (2009). Generation Y: Are they really digital natives or more like digital refugees. Synergy, 7(1), 31–40.

Dale, V. H., Brown, S., Haeuber, R. A., Hobbs, N. T., Huntly, N., Naiman, R. J., et al. (2000). Ecological principles and guidelines for managing the use of land. Ecological Applications, 10(3), 639–670.

Decker, D. J., Organ, J. F., & Jacobson, C. A. (2009). Why should all Americans care about the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation? Transactions of the 74th North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference, 74, 32–36.

Dizard, J. E. (1999). Going wild: hunting, animal rights, and the contested meaning of nature. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Dratch, P., & Kahn, R. (2011). Moving beyond the model. The Wildlife Professional, Summer, 61–63.

Duda, M. D., Bissell, S. J., & Young, K. C. (1995). Factors related to hunting and fishing participation in the United States. Phase V: Final Report. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Reference Service Report.

Duda, M. D., Jones, M. F., & Criscione, A. (2010). The sportsman’s voice: Hunting and fishing in America. State College, PA: Venture Publishing Inc.

Dunlap, T. R. (1988). Saving America’s wildlife: Ecology and the American mind, 1850–1990. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Eagan, K. (2010). Governing Wisconsin: Public lands. Report published by the Legislative Reference Bureau. No. 32. June. http://www.legis.wi.gov/lrb/GW.

Gill, R. B. (1996). The wildlife professional subculture: The case of the crazy aunt. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 1, 60–69.

Glenn, N. D. (1976). Cohort analysts’ futile quest: Statistical attempts to separate age, period and cohort effects. American Sociological Review, 41, 900–904.

Glenn, N. D. (2005). Cohort analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Haider-Markel, D. P., & Joslyn, M. R. (2008). Beliefs about the origins of homosexuality and support for gay rights. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(2), 291–310.

Heberlein, T. A. (1987). Stalking the predator: A profile of the American hunter. Environment, 29(7), 6–11, 30–33.

Heberlein, T., Serup, B., & Ericsson, G. (2008). Female hunting participation in North America and Europe. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 13(6), 443–458.

Heberlein, T., & Thomson, E. (1996). Changes in US hunting participation, 1980–1990. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 1(1), 85–86.

Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (2000). Millennials rising: The next great generation, First edition. New York: Vintage Books.

Jacobson, C. A., Decker, D. J., & Carpenter, L. (2007). Securing alternative funding for wildlife management: Insight from agency leaders. Journal of Wildlife Management, 71, 2106–2113.

Kilpatrick, H. J., & Labonte, A. M. (2003). Deer hunting in a residential community: The community’s perspective. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 31, 340–348.

Kilpatrick, H. J., LaBonte, A. M., & Seymour, J. T. (2002). A shotgun-archery deer hunt in a residential community: Evaluation of hunt strategies and effectiveness. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 30, 478–486.

Kitagawa, E. M. (1955). Components of a difference between two rates. American Statistical Association Journal, 50(272), 1168–1194.

Land, K. (2011). Age-period-cohort analysis: New models, methods, and empirical analyses. Presentation at Indiana University, April 15, 2011. Accessed online May 20, 2011.

Leisure Trends Group. (2008). Gen Y not digging nature. LeisureTRAK ® Report 7 (1), March.

Leonard, J. (2007). Fishing and hunting recruitment and retention in the U.S. from 1990–2005. Report 2001–11. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Louv, R. (2005). Last child in the woods. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

Mahoney, S. P. (2009). Recreational hunting and sustainable wildlife use in North America. In B. Dickson, J. Hutton, & W. M. Adams (Eds.), Recreational hunting, conservation and rural livelihoods: Science and practice (pp. 266–281). Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell.

Manfredo, M. J., & Zinn, H. C. (1996). Population change and its implications for wildlife management in the new west: A case study of Colorado. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 1, 62–74.

Mason, W. M., & Fienberg, S. E. (1985). Cohort analysis in social research: Beyond the identification problem (1st Edn.). New York: Springer.

Mason, K. O., Mason, W. H., Winsborough, H. H., & Poole, K. (1973). Some methodological issues in cohort analysis of archival data. American Sociological Review, 38, 242–258.

Miller, C., & Vaske, J. (2003). Individual and situational influences on declining hunter effort in Illinois. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 8, 263–276.

Mockrin, M., Aiken, R. A., & Flather, C. H. (In review). Trends in Wildlife-Associated Recreation: A technical document supporting the 2010 USDA Forest Service RPA assessment. USDA General Technical Report-RMRS-XX.

National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Related Recreation (FHWAR). (1980, 1985, 1991, 1996, 2001, 2006). U.S. Census Bureau.

Nelson, M. P., Vucetich, J. A., Paquet, P. C., & Bump, J. K. (2011). An inadequate construct? The Wildlife Professional, Summer, 58–60.

Organ, J. F., Mahoney, S. P., & Geist. V. (2010). Born in the hands of hunters. The Wildlife Professional, Fall, 22–27.

Peterson, M. N. (2004). An approach for demonstrating the social legitimacy of hunting. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 32, 310–321.

Peterson, M. N., Hansen, H. P., Peterson, M. J., & Peterson, T. R. (2010). How hunting strengthens social awareness of coupled human and natural systems. Wildlife Biology in Practice, 6(2), 127–143.

Poudyal, N., Cho, S. H., & Bowker, J. M. (2008). Demand for resident hunting in the Southeastern United States. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 13, 158–174.

Presser, L., & W. V. Taylor. (2011). An autoethnography of hunting. Crime, Law and Social Change, 55, 483–494.

Regan, R. (2010). Priceless but not free: Why all nature lovers should contribute to conservation. The Wildlife Professional, Fall, 39–41.

Reiger, J. F. (2001). American sportsmen and the origins of conservation. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press.

Responsive Management. (1999). Hunters’, anglers’, and boaters’ awareness of and attitudes toward the federal aid in sport fish and wildlife restoration programs. International Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Harrisonburg, VA.

Responsive Management. (2003). Factors related to hunting and fishing participation among the nation’s youth. Harrisonburg, VA.

Responsive Management. (2005). Public opinion on fish and wildlife management issues and the reputation and credibility of fish and wildlife agencies in the southeastern United States: Southeastern region report. Harrisonburg, VA.

Ryder, N. B. (1965). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review, 30(6), 843–861.

Sassi, F., Devaux, M., Cecchini, M., & Rusticelli, E. (2009). The obesity epidemic: analysis of past and projected future trends in selected OECD countries. OECD Publishing http://ideas.repec.org/p/oec/elsaad/45-en.html. Accessed June 23, 2011.

Scarce, R. (1999). Who or what is in control here? Understanding the social context of salmon biology. Society and Natural Resources, 12(8), 763–776.

Schwadel, P. (2011). Age, period, and cohort effects on religious activities and beliefs. Social Science Research, 40(1), 181–192.

Smith, H. L. (2004). Response: Cohort analysis redux. Sociological Methodology, 34, 111–119.

Southwick and Associates. (2007). Hunting in America: An Economic Engine and Conservation Powerhouse. Produced for the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies with funding from Multistate Conservation Grant Program, 2007.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Hunting License Report, 1958–2010.

Vaske, J. J., Timmons, N. R., Beaman, J., & Petchenik, J. (2004). Chronic wasting disease in Wisconsin: Hunter behavior, perceived risk, and agency trust. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 9, 193–209.

Voss, P. (2007). Projections of the Wisconsin population by single year of age, sex, and race, 2000–2030. Madison: Applied Population Laboratory, University of Wisconsin.

Willging, R. C. (2008). On the hunt: The history of deer hunting in Wisconsin (1st Edn.). Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Williams, S. (2010). Wellspring of wildlife funding. The Wildlife Professional, Fall, 35–38.

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. (2000–2010). Wisconsin resident deer hunter license sales records.

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. (2001). Participation trends and projections in outdoor recreation, 14 pp.

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. (2009). Your investment in Wisconsin’s Fish and Wildlife 2008–2009. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Woolf, A., & Roseberry, J. L. (1998). Deer management: Our profession’s symbol of success or failure? Wildlife Society Bulletin, 26, 515–521.

Yang, Y. (2008). Trends in US adult chronic disease mortality, 1960–1999: Age, period, and cohort variations. Demography, 45, 387–416.

Yang, Y., Fu, W. J., & Land, K. C. (2004). A methodological comparison of age-period-cohort models: The intrinsic estimator and conventional generalized linear models. Sociological Methodology, 34, 75–110.

Yang, Y., Fu, W. J., Schulhofer-Wohl, S., & Land, K. C. (2008). The intrinsic estimator for age-period-cohort analysis: What it is and how to use it. American Journal of Sociology, 113(6), 1697–1736.

Acknowledgments

This project was developed as a joint effort between the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and the Applied Population Laboratory (APL) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. It was funded by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. The authors wish to acknowledge our colleagues in the APL including Jennifer Huck who played an important role in the early phases of this study with data organization and analysis, Roz Klaas who handled more recent data organization and performed geographical analysis, and David Long who provided critical feedback on the paper; Tom Heberlein who introduced the authors, encouraged us to work together to better understand hunter population dynamics, and who continues to push us to expand and think critically about our work; and Betty Thomson and Jim Raymo at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Center for Demography and Ecology who commented on early drafts of this paper. Previous versions of the paper were presented at the Southern Demographic Association meeting in Greenville, SC in 2008, at the Population Association of America meeting in Detroit in 2009, and at the International Symposium for Society and Resource Management in Madison, WI in 2011. Feedback we received from participants at these meetings has been important to the development of the paper and the story. We would also like to recognize and thank the Southern Demographic Association Award Committee for awarding a prior version of this paper the Walter Terrie Award for Best Paper in Applied Demography and for the valuable feedback we received from the committee. Finally, we thank the editor and peer reviewers for their useful comments and suggestions that improved the clarity of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Winkler, R., Warnke, K. The future of hunting: an age-period-cohort analysis of deer hunter decline. Popul Environ 34, 460–480 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-012-0172-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-012-0172-6