Abstract

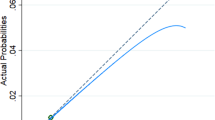

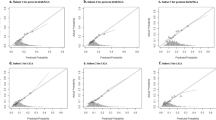

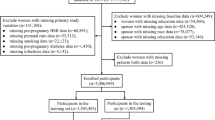

Objective Preterm birth is a leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality. Prevention strategies rarely focus on preconception care. We sought to create a preconception nomogram that identifies nonpregnant women at highest risk for preterm birth using the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) surveillance data. Methods We used PRAMS data from 2004 to 2009. The odds ratios (ORs) of preterm birth for each preconception variable was estimated and adjusted analyses were conducted. We created a validated nomogram predicting the probability of preterm birth using multivariate logistic regression coefficients. Results 192,208 cases met inclusion criteria. Demographic/maternal health characteristics and associations with preterm birth and ORs are reported. After validation, we identified the following significant predictors of preterm birth: prior history of preterm birth or low birth weight baby, prior spontaneous or elective abortion, maternal diabetes prior to conception, maternal race (e.g., non-Hispanic black), intention to get pregnant prior to conception (i.e., did not want or wanted it sooner), and smoking prior to conception (p < 0.05). Overall, our preconception preterm risk model correctly classified 76.1 % of preterm cases with a negative predictive value (NPV) of 76.7 %. A nomogram using a 0–100 scale illustrates our final preconception model for predicting preterm birth. Conclusion This preconception nomogram can be used by clinicians in multiple settings as a tool to help predict a woman’s individual preterm birth risk and to triage high-risk non-pregnant women to preconception care. Future studies are needed to validate the nomogram in a clinical setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ayoola, A. B., Stommel, M., & Nettleman, M. D. (2009). Late recognition of pregnancy as a predictor of adverse birth outcomes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 201(156), e1–e6.

Balachandran, V. P., Gonen, M., Smith, J. J., & DeMatteo, R. P. (2015). Nomograms in oncology: More than meets the eye. The lancet Oncology, 16(4), e173–e180.

Bastek, J. A., Sammel, M. D., Srinivas, S. K., et al. (2012). Clinical prediction rules for preterm birth in patients presenting with preterm labor. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 119, 1119–1128.

Bediako, P. T., BeLue, R., & Hillemeier, M. M. (2015). A comparison of birth outcomes among Black, Hispanic, and Black Hispanic women. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 2(4), 573–582.

Berghella, V., Odibo, A., To, M., Rust, O., & Althusius, S. (2009). Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography: Meta-analysis of trials using individual patient-level data. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 106, 181–189.

Colaizy, T. T., Saftlas, A. F., & Morriss, F. H, Jr. (2012). Maternal intention to breast-feed and breast-feeding outcomes in term and preterm infants: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2000–2003. Public Health Nutrition, 15, 702–710.

Creasy, R. K., Gummer, B. A., & Liggins, G. C. (1980). System for predicting spontaneous preterm birth. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 55, 692–695.

Culhane, J. F., & Goldenberg, R. L. (2011). Racial disparities in preterm birth. Seminars in Perinatology, 35, 234–239.

Davey, M.-A., Watson, L., Rayner, J. A., & Rowlands, S. (2011). Risk scoring systems for predicting preterm birth with the aim of reducing associated adverse outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004902.pub4.

Goldenberg, R. L., Culhane, J. F., Iams, J. D., & Romero, R. (2008). Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. The Lancet, 371, 75–84.

Greenland, S. (1995). Dose-response and trend analysis in epidemiology: Alternatives to categorical analysis. Epidemiology, 6, 356–365.

Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Ventura, S. J. (2006). Births: Preliminary data for 2005. National Vital Statistics Reports, 55, 1–18.

Harrell, F. E, Jr., Margolis, P. A., Gove, S., et al. (1998). Development of a clinical prediction model for an ordinal outcome: The World Health Organization Multicentre Study of Clinical Signs and Etiological agents of Pneumonia, Sepsis and Meningitis in Young Infants. WHO/ARI Young Infant Multicentre Study Group. Statistics in Medicine, 17, 909–944.

Harris-Requejo, J., & Merialdi, M. (2010). The global impact of preterm birth. In V. Berghella (Ed.), Preterm birth: Prevention and management (pp. 1–7). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Heagerty, P., Lumley, T., & Pepe, M. (2000). Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics, 56, 337–344.

Healthy People 2010. (2000). With understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Henderson, L. J. (1928). Blood: A study in general physiology (vol. 3, p. 148). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press (Fig. 141).

Henshaw, S. K. (1998). Unintended pregnancy in the United States. Family Planning Perspectives, 30(24–9), 46.

Honest, H., Bachmann, L. M., Sundaram, R., Gupta, J. K., Kleijnen, J., & Khan, K. S. (2004). The accuracy of risk scores in predicting preterm birth—A systematic review. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 24, 343–359.

Iams, J. D., Goldenberg, R. L., Meis, P. J., et al. (1996). The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. New England Journal of Medicine, 334, 567–572.

Johnson, K., Posner, S. F., Biermann, J., et al. (2006). Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care–United States. A report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 55, 1–23.

Kanninen, T. T., Sisti, G., Ramer, I., Goldschlag, D., Witkin, S. S., & Spandorfer, S. D. (2015). Predictive biomarkers of preterm delivery in women with ongoing IVF pregnancies. Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 112, 58–62.

Kim, S. M., Romero, R., Lee, J., Chaemsaithong, P., Lee, M. W., Chaiyasit, N., et al. (2015). About one-half of early spontaneous preterm deliveries can be identified by a rapid matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8) bedside test at the time of mid-trimester genetic amniocentesis. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 7, 1–9.

Lockwood, C. J., Senyei, A. E., Dische, M. R., et al. (1991). Fetal fibronectin in cervical and vaginal secretions as a predictor of preterm delivery. New England Journal of Medicine, 325, 669–674.

Meis, P., Klebanoff, M., Thom, E., et al. (2003). Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 2379–2385.

Papiernik-Berkhauer, E. (1969). Coefficient de risque d’accouchement prématuré. Presse Medicale, 77, 793–794.

Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Home. (2011). http://www.cdc.gov/prams. Accessed December 20, 2011.

Robins, J., & Greenland, S. (1986). The role of model selection in causal inference from nonexperimental data. American Journal of Epidemiology, 123, 392–402.

Schoen, C. N., Tabbah, S., Iams, J. D., Caughey, A. B., & Berghella, V. (2015). Why the United States preterm birth rate is declining. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 213(2), 175–180.

Shulman, H. B., Gilbert, B. C., Msphbrenda, C. G., & Lansky, A. (2006). The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): Current methods and evaluation of 2001 response rates. Public Health Reports, 121, 74–83.

Villar, J., Papageorghiou, A. T., Knight, H. E., et al. (2012). The preterm birth syndrome: A prototype phenotypic classification. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 206, 119–123.

Whitehead, N., & Helms, K. (2010). Racial and ethnic differences in preterm delivery among low-risk women. Ethnicity and Disease, 20, 261–266.

Acknowledgments

PRAMS Working Group: Alabama—Qun Zheng, M.S. Alaska—Kathy Perham-Hester, M.S., M.P.H. Arkansas— Mary McGehee, Ph.D. Colorado—Alyson Shupe, Ph.D. Connecticut—Jennifer Morin, M.P.H. Delaware— George Yocher, M.S. Florida— Kelsi E. Williams Georgia— Chinelo Ogbuanu, M.D., M.P.H., Ph.D. Hawaii— Jane Awakuni Illinois—Theresa Sandidge, MA Iowa —Sarah Mauch, M.P.H. Louisiana— Amy Zapata, M.P.H. Maine—Tom Patenaude, M.P.H. Maryland—Diana Cheng, M.D. Massachusetts— Emily Lu, M.P.H. Michigan— Patricia McKane Minnesota—Judy Punyko, Ph.D., M.P.H. Mississippi— Brenda Hughes, M.P.P.A. Missouri—Venkata Garikapaty, M.Sc., M.S., Ph.D., M.P.H. Montana—JoAnn Dotson Nebraska—Brenda CoufalI New Hampshire—David J. Laflamme, Ph.D., M.P.H. New Jersey—Ingrid M. Morton, M.S. New Mexico—Eirian Coronado, M.P.H. New York State—Anne Radigan-Garcia New York City—Candace Mulready-Ward, M.P.H. North Carolina— Kathleen Jones-Vessey, M.S. North Dakota—Sandra Anseth Ohio—Connie Geidenberger Ph.D. Oklahoma—Alicia Lincoln, M.S.W., M.S.P.H. Oregon—Kenneth Rosenberg, M.D., M.P.H. Pennsylvania—Tony Norwood Rhode Island—Sam Viner-Brown, Ph.D. South Carolina—Mike Smith, MSPH Texas— Tanya Guthrie, Ph.D. Tennessee—Ramona Lainhart, Ph.D. Utah—Laurie Baksh, M.P.H. Vermont—Peggy Brozicevic Virginia—Christopher Hill, M.P.H., C.P.H. Washington—Linda Lohdefinck West Virginia—Melissa Baker, M.A. Wisconsin—Katherine Kvale, Ph.D. Wyoming—Amy Spieker, M.P.H. CDC PRAMS Team, Applied Sciences Branch, Division of Reproductive Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mehta-Lee, S.S., Palma, A., Bernstein, P.S. et al. A Preconception Nomogram to Predict Preterm Delivery. Matern Child Health J 21, 118–127 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2100-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2100-3