Abstract

As refugee populations continue to age in the United States, there is a need to prioritize screening for chronic illnesses, including cancer, and to characterize how social and cultural contexts influence beliefs about cancer and screening behaviors. This study examines screening rates and socio-cultural factors influencing screening among resettled refugee women from Muslim-majority countries of origin. A systematic and integrative review approach was used to examine articles published from 1980 to 2019, using PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. A total of 20 articles met the inclusion criteria. Cancer screening rates among refugee women are lower when compared to US-born counterparts. Social and cultural factors include religious beliefs about cancer, stigma, modesty and gender roles within the family context. The findings of this review, suggest that resettled refugee women underutilize preventive services, specifically mammography, Pap test and colonoscopy screening, and whose perceptions and behaviors about cancer and screening are influenced by social and cultural factors.

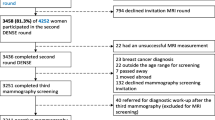

Adapted from Ref. [15]

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Reyes AM, Miranda PY. Trends in cancer screening by citizenship and health insurance, 2000–2010. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(3):644–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0091-y.

United States Department of State Fact Sheet: Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. 2018. https://www.state.gov/j/prm/releases/factsheets/2018/277838.htm. Accessed 15 May 2018.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Global Trends Forced Displacement 2016 Report. 2016. https://www.unhcr.org/5943e8a34.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2018.

Morris MD, Popper ST, Rodwell TC, Brodine SK, Brouwer KC. Healthcare barriers of refugees post-resettlement. J Community Health. 2009;34(6):529–38.

McKearny M, Newbold B. Barriers to care: the challenges for Canadian refugees and their healthcare providers. J Refug Stud. 2010;23(4):523–45.

Latif F et al. Ethnicity differences in breast cancer stage at the time of diagnosis in Norway. Scand J Surg. 2015;104(4):248–53. Accessed 15 May 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. Refugee Health Guidelines. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/domestic/general/discussion/cancer-screening.html. Accessed 25 May 2018.

National Cancer Institute. Cancer screening Tests. 2018. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/screening/screening-tests. Accessed 25 May 2018.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF]. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2018.

American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Guidelines for the Early Detection of Cancer. 2018. https://www.cancer.org/healthy/find-cancer-early/cancer-screening-guidelines/american-cancer-society-guidelines-for-the-early-detection-of-cancer.html. Accessed 25 May 2018.

Lofters A, et al. Cervical cancer screening among women from Muslim majority countries in Ontario, Canada. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2017;26(10):1493–9.

McDermott S, et al. Cancer incidence among Canadian immigrants, 1980–1998: results from a National Cohort Study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;13(1):15–26.

O’Keefe EB, Meltzer J, Bethea T. Health disparities and cancer: racial disparities in cancer mortality in the United States, 2000–2010. Front Public Health 2015; 3:51.

John E, Phipps A, Davis A, Koo J. Migration history, acculturation and breast cancer risk in Hispanic women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2005;14(12):2905–13.

McLeroy K, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Behav. 1988;15(4):351–77.

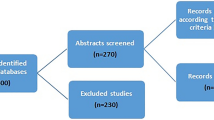

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(2):546–53.

Carroll J, et al. Knowledge and beliefs about health promotion and preventive health care among Somali women in the US. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28(4):360–80.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures, 2017–2018.

Goel MS, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening: the importance of foreign birth as a barrier to care. JGIM. 2003;18(12):1028–35.

Attum B, Waheed A, Shamoon Z. Cultural competence in the care of Muslim patients and their families. [Updated 15 Jun 2019]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499933/.

Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018). CASP (Qualitative) Checklist. Accessed 25 May 2018.

Fowkes FG, Fulton PM. Critical appraisal of published research: introductory guidelines. BMJ. 1991;302(6785):1136–40.

Piwowarczyk L, et al. Pilot evaluation of a health promotion program for African immigrant and refugee women: the UJAMBO Program. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(1):219–23.

Saadi A, Bond B, Percac-Lima S. Bosnian, Iraqi and Somali refugee women speak: a comparative qualitative study of refugee health beliefs on preventive health and breast cancer screening. Women’s Health Issues. 2015;25(5):501–8.

Shirazi M, et al. Afghan immigrant women’s knowledge and behaviors around breast cancer screening. Psychooncology. 2013;22(8):1705–17.

Gondek M, et al. Engaging immigrant and refugee women in breast health education. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(3):593–8.

Pratt R et al. Views of Somali women and men on the use of faith-based messages promoting breast and cervical cancer screening for Somali women: a focus group study. BMC Public Health 2017; 17:270.

Morrison TB, et al. Disparities in preventive health services among Somali immigrants and refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(6):968–74.

Percac-Lima S, et al. Decreasing disparities in breast cancer screening in refugee women using culturally tailored patient navigation. JGIM. 2013;28(11):1463–8.

Pickle S, Altshuler M, Scott K. Cervical cancer screening outcomes in a refugee population. J Immigr Refug Stud. 2014;12(1):1–8.

Jillson I, et al. Knowledge and practice of colorectal cancer screening in a suburban group of Iraqi American women. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(2):284–93.

Morrison TB, et al. Cervical cancer screening adherence among Somali immigrants and refugees to the United States. Health Care Women Int. 2013;34(11):980–8.

Murray KE, Mohamed AS, Ndunduyenge GG. Health and prevention among East African women in the U.S. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2013; 24(1), 233–246.

Zhang Y, et al. Providers' perspectives on promoting cervical cancer screening among refugee women. J Community Health. 2016;42(3):583–90.

Al-Amoudi S, et al. Breaking the silence: breast cancer knowledge and beliefs among Somali Muslim women in Seattle. Washington. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(5):608–16.

Ghebre R, et al. Cervical cancer: barriers to screening in the Somali community in Minnesota. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(3):722–8.

Reed SD, et al. Knowledge and attitudes regarding routine health screening and prevention in Somali, Vietnamese, and Latina women. Clin J Women's Health. 2002;2(3):105–11.

Allen H, et al. Facilitators and barriers of cervical cancer screening and Human Papilloma Virus vaccination among Somali refugee women in the United States: a qualitative analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2019;30(1):40–55.

Watanabe-Galloway S, et al. Cancer community education in Somali refugees in Nebraska. J Community Health. 2018;43:929–36.

Raymond N, et al. Culturally informed views on cancer screening: a qualitative research study of the differences between older and younger Somali immigrant women. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1188.

Saadi A, Bond B, Percac-Lima S. Perspectives on preventive health care and barriers to breast cancer screening among Iraqi women and refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(4):633–9.

Samuel P, et al. Breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening rates amongst female Cambodian, Somali, and Vietnamese immigrants in the USA. Int J Equity Health. 2009;14(8):30.

Yao N, Hillemeier MM. Disparities in mammography rate among immigrant and native-born women in the U.S.: progress and challenges. J Immigr Minor Health; 2014;16(4):613–21.

QuickStats: Percentage of U.S. Women aged 21–65 years who never had a papanicolaou test (pap test), by place of birth and length of residence in the United States—National Health Interview Survey, 2013 and 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:346.

Elder JP et al. Promoting cancer screening among churchgoing Latinas: Fe en Acci/faith in action 2017. Health Educ Res. 2017;32(2):163–73.

Holt CL, et al. Translating evidence-based interventions for implementation: Experiences from Project HEAL in African American churches. Implement Sci. 2014;9:66.

Torres E, et al. Understanding factors influencing Latina women’s screening behavior: a qualitative approach. Health Educ Res. 2013;28(5):772–83.

Lee E, et al. The effect of a couples intervention to increase breast cancer screening among Korean Americans. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(3):E185–E193193.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Siddiq, H., Alemi, Q., Mentes, J. et al. Preventive Cancer Screening Among Resettled Refugee Women from Muslim-Majority Countries: A Systematic Review. J Immigrant Minority Health 22, 1067–1093 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-019-00967-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-019-00967-6