Abstract

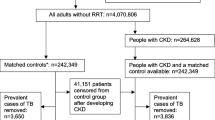

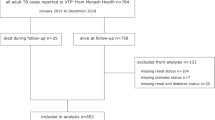

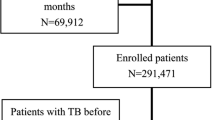

The association between chronic kidney disease (CKD) and tuberculosis disease (TB) has been recognized for decades. Recently CKD prevalence is increasing in low- to middle-income countries with high TB burden. Using data from the required overseas medical exam and the recommended US follow-up exam for 444,356 US-bound refugees aged ≥ 18 during 2009–2017, we ran Poisson regression to assess the prevalence of TB among refugees with and without CKD, controlling for sex, age, diabetes, tobacco use, body mass index ( kg/m2), prior residence in camp or non-camp setting, and region of birth country. Of the 1117 (0.3%) with CKD, 21 (1.9%) had TB disease; of the 443,239 who did not have CKD, 3380 (0.8%) had TB. In adjusted analyses, TB was significantly higher among those with than without CKD (prevalence ratio 1.93, 95% CI: 1.26, 2.98, p < 0.01). Healthcare providers attending to refugees need to be aware of this association.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Pradhan RP, Katz LA, Nidus BD, Matalon R, Eisinger RP. Tuberculosis in dialyzed patients. Jama. 1974;229(7):798–800.

Hsu HWLC, Wang MH, Chiang CK, Lu KC. A review of chronic kidney disease and the immune system: a special form of immunosenescence. J Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2014;3(2):1–6.

Kato S, Chmielewski M, Honda H, et al. Aspects of immune dysfunction in end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1526–33.

Hossain MP, Goyder EC, Rigby JE, El Nahas M. CKD and poverty: a growing global challenge. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(1):166–74.

Waaler HT. Tuberculosis and poverty. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6(9):745–6.

Weil EJ, Curtis JM, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Nelson RG. The impact of disadvantage on the development and progression of diabetic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74(Suppl 1):32–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Chronic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/kidney_factsheet.pdf. Accessed 11 June 2017.

Bello AK, Levin A, Tonelli M, et al. Assessment of global kidney health care status. Jama. 2017;317(18):1864–81.

Barsoum RS. Chronic kidney disease in the developing world. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(10):997–99.

Romanowski K, Clark EG, Levin A, Cook VJ, Johnston JC. Tuberculosis and chronic kidney disease: an emerging global syndemic. Kidney Int. 2016;90(1):34–40.

Ronald LA, Campbell JR, Balshaw RF, et al. Predicting tuberculosis risk in the foreign-born population of British Columbia, Canada: study protocol for a retrospective population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e013488.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Technical instructions for panel physicians and civil surgeons. 2016; https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/exams/ti/panel/technical-instructions/panel-physicians/medical-history-physical-exam.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disease surveillance among newly arriving refugees and immigrants — electronic disease notification system, United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;62(2013):1–20.

United States Department of State. Countries Reg. 2017; https://www.state.gov/countries/. Accessed 11 Feb 2017.

WHO, Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363(9403):157–163.

Posey DL, Naughton MP, Willacy EA, et al. Implementation of new TB screening requirements for U.S.-bound immigrants and refugees–2007–2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(11):234–6.

Benoit SR, Gregg EW, Jonnalagadda S, Phares CR, Zhou W, Painter JA. Association of diabetes and tuberculosis disease among US-bound adult refugees, 2009–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(3):543–5.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis screening and treatment technical instructions (TB TIs) using cultures and directly observed therapy (DOT) for panel physicians. 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/exams/ti/panel/tuberculosis-panel-technical-instructions.html. Accessed 08 Jan 2017.

Levin A, et al. Kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) CKD work group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(1):1–150.

Korn EL, Graubard BL. Analysis of health surveys. wiley series in probability and statistics. New York: Wiley; 1999.

Woeltje KF, Mathew A, Rothstein M, Seiler S, Fraser VJ. Tuberculosis infection and anergy in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31(5):848–52.

Hussein MM, Mooij JM, Roujouleh H. Tuberculosis and chronic renal disease. Semin Dial. 2003;16(1):38–44.

Malik GH, Al-Harbi AS, Al-Mohaya S, et al. Eleven years of experience with dialysis associated tuberculosis. Clin Nephrol. 2002;58(5):356–62.

Vandermarliere A, Van Audenhove A, Peetermans WE, Vanrenterghem Y, Maes B. Mycobacterial infection after renal transplantation in a Western population. Transpl Infect Dis. 2003;5(1):9–15.

Chen CH, Lian JD, Cheng CH, Wu MJ, Lee WC, Shu KH. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection following renal transplantation in Taiwan. Transpl Infect Dis. 2006;8(3):148–56.

Mendenhall E, Kohrt BA, Norris SA, Ndetei D, Prabhakaran D. Non-communicable disease syndemics: poverty, depression, and diabetes among low-income populations. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):951–63.

Jeon CY, Murray MB. Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of active tuberculosis: a systematic review of 13 observational studies. PLoS Med. 2008;5(7):e152.

Riza AL, Pearson F, Ugarte-Gil C, et al. Clinical management of concurrent diabetes and tuberculosis and the implications for patient services. Lancet Diab Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):740–53.

Bardenheier BH, Phares CR, Simpson D, et al. Trends in chronic diseases reported by refugees originating from burma resettling to the United States from camps versus urban areas during 2009–2016. J Immigr Minor Health. 2018 1–11.

Dooley KE, Chaisson RE. Tuberculosis and diabetes mellitus: convergence of two epidemics. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(12):737–46.

World Health Organization. Tuberculosis Fact Sheet. 2017; http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/.

Mallipattu SK, Salem F, Wyatt CM. The changing epidemiology of HIV-related chronic kidney disease in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Kidney Int. 2014;86(2):259–65.

Centers for Disease and Prevention (CDC, and US Department of Health and Human Services. Medical examination of aliens–removal of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection from definition of communicable disease of public health significance. Final rule. Fed Reg. 2009;74(210):56547–62.

World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. Geneva, Switzerland 2014.

Cohn DL, et al. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(4):221–47.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors would like to thank Ms. Jenique Meekins for her help with editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Informed Consent

No consent forms were needed.

Research involving Human and Animal Participants

All data used for this analysis were collected in the course of routine refugee resettlement practices. This project was determined to be non-research by a CDC human subjects advisor; IRB review was not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bardenheier, B.H., Pavkov, M.E., Winston, C.A. et al. Prevalence of Tuberculosis Disease Among Adult US-Bound Refugees with Chronic Kidney Disease. J Immigrant Minority Health 21, 1275–1281 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-00852-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-00852-8