Abstract

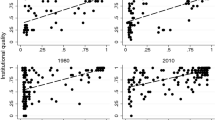

Over the last two centuries, many countries experienced regime transitions toward democracy. We document this democratic transition over a long time horizon. We use historical time series of income, education and democracy levels from 1870 to 2000 to explore the economic factors associated with rising levels of democracy. We find that primary schooling, and to a weaker extent per capita income levels, are strong determinants of the quality of political institutions. We find little evidence of causality running the other way, from democracy to income or education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Democracy in America, Volume 1, chapter 9, “the main causes that tend to maintain a democratic republic in the United States”.

See also Gundlach and Paldam (2012) for a discussion of long run relationship between economic development and democracy, arguing that causality runs from the former to the latter.

Using a more micro approach in Kenya, Friedman et al. (2011) also find that “increased human capital did not produce more pro-democratic or secular attitudes and strengthened ethnic identification”. Whether this holds more broadly at the level of countries and realized democratic institutions rather than attitudes remains debated. Another view is Fayad, Bates and Hoeffler (2011), who uncover a negative effect of income shocks on democracy. Finally, Grosjean and Senik (2011) fail to find a significant effect of economic liberalization on democratization, suggesting instead that democratization may facilitate economic liberalization.

When studying the relationship between democracy and income, the maximal sample size is 69 countries, while it is 70 countries when focusing only on education.

The annual convergence rate is given by \(-log(\rho )/T\) where \(\rho \) is the estimated coefficient of initial democracy in an absolute convergence regression, and \(T\) is the length of the period over which the difference in democracy is calculated. There are respectively 34, 39 and 59 countries involved in the latter computation. In the balanced panel, the results are almost identical: a convergence process has taken place in the 1910–1960 and 1960–2000 periods at an annual rate of respectively \(3.2~\%\) and \(3.6~\%\). In the first period, convergence occurred but only among a club of advanced democracies.

Before 1960, the main source for education data is Mitchell (2003)’s statistical yearbooks. After 1960, they relied on the Cohen and Soto (2007) series, adjusted for differential mortality across educational groups.

A short list of references might include Bourguignon and Morrisson (2002), describing the world income distribution since 1820; Galor and Weil (2000) and Galor (2005); Galor (2011), analyzing the joint variations of income and population over the long run as well as the structural forces that have triggered the Industrial Revolution; O’Rourke and Williamson (1999) and Hatton and Williamson (2005), focusing on the effect of globalization on economic performance; Morrisson and Murtin (2009); Morrisson and Murtin (2013), describing the spread of education at a global level; Murtin (2013) investigating the determinants of the demographic transition over the twentieth century.

We have used an Epanchenikov kernel with bandwidth adjusted to the finite sample size. We used the balanced panel of countries, but results are qualitatively the same with the unbalanced panel.

We also considered a simple FE estimator, without including lagged democracy on the right hand side. These results appeared in the working paper version of this study (Murtin and Wacziarg 2011).

We are grateful to an anonymous referee for pointing out these concerns to us in terms close to the discussion that follows.

Acemoglu et al. (2008) raise a similar point.

We programmed all the estimation and simulation routines ourselves. With a regular personal computer, it takes about 40-50 hours to run a single regression. Thus, in our application we only replicate our baseline results using BC, and continue to report system GMM results for other specifications.

Lokshin (2009) is the only other empirical application of the Bun-Carree estimator that we are aware of.

Inclusion into the sample is assumed to be an absorbing state, namely countries do not exit the sample once they have entered it. Inclusion takes place at the first date \(t_{0}\) such that \(u_{i,t_{0}}>\tau \).

We do not consider very short panels with \(T=2\) or \(T=3\) as Lokshin (2009) exhibits non-convergence patterns for such very short panels.

The estimation yields \((\mu ^{y}=0.097,\mu ^{x}=1.7e-4,g^{y}=0.014,g^{x}=0.055,\sigma _{\eta ^{y}}^{2}=0.021,\sigma _{\eta ^{x}}^{2}=0.091,\sigma _{\varepsilon }^{2}(0)=0.263,\sigma _{\xi }^{2}=0.295)\).

As the magnitude of the latter effect pertaining to steady-state democracy levels amounts to \(0.118/(1-0.509)\times log(2)=0.166\)

In statistical terms, this raises the issue of the measurement of democracy, which is proxied by a bounded variable. Even if some countries have already converged towards the maximum reported level of democracy at the initial date, institutions have kept on evolving, most likely improving, within these countries. Benhabib et al. (2011) account for the censoring of the democracy variable and find, similarly to us, a significant coefficient on log GDP per capita.

In their paper, Acemoglu et al. (2008) include both a set of country fixed effects and of time period firxed effects. We include time period fixed effects in all of our panel regressions.

The divergence in results with Acemoglu et al. (2008) can also in part be explained by the difference in the time span used across the two analyses. Acemoglu et al. (2008) consider 25 year time spans, while the present study focuses on decennial time spans. When using a longer time span of 30 years, we also found that lagged income was insignificant with a DFE estimator. However, it was still highly significant when using a BB estimator.

However, AB estimates for the corresponding specifications are available upon request.

This finding may be interpreted as the sign of multicollinearity problems when variables are introduced altogether.

We also ran regressions using the total number of years of education in the adult population (the sum of primary, secondary and tertiary). We found mixed evidence that the overall stock of education was significantly associated with democracy. Results were strongest using the state-of-the-art BB estimator irrespective of the period under consideration. Results for overall educational attainment are available upon request.

Over the period 1960–2000, Castelló-Climent (2008) find that the education level of the first three quintiles of the education distribution is a more robust determinant of democracy than average years of schooling in the population. As the population at the bottom of the education distribution receive only primary education in early stages of economic development, her measure and ours are quite similar to each other.

The corresponding empirical results are available upon request.

Results are available upon request. The 19 countries in the balanced panel were Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Canada, Switzerland, Spain, France, the United Kindgom, Greece, Hungary, Iran, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, Portugal, Sweden, Thailand, the United States, and Venezuela. While it may be tempting to assume that countries for which data is constinuously available since 1870 may not have experienced large shifts in democracy ovr the 1870–2000 period, this is not the case, as demonstrated by the right-hand panel of Table 1, which summarizes the level of democracy per period for this subsample.

This variable is taken from the dataset on education by age borrowed from the same sources as those underlying Morrisson and Murtin (2009).

In results available upon request, we introduced a cubic in the level of democracy to detect potentially non-linear effects as suggested by Lindert (2004). We could not find any evidence of non-linearity.

In contrast to Lindert’s view that the extension of the suffrage should lead to differences in educational policy and spending, Mulligan, Gil and Sala-i-Martin (2004, 2010) show that, on a wide array of policy metrics, including Social Security, democracies do not significantly differ from non-democracies. This is consistent with our finding that democracy does not causally affect educational attainment very strongly.

This finding may be explained by the existence of country-specific deterministic trends that are not well captured by the set of time dummies, leaving room for the existence of an integrated process of order 1 that contaminates the residuals and biases upward the autocorrelation coefficient.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2000). Why did the west extend the Franchise? Democracy, inequality, and growth in historical perspective. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(4), 1167–1199.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91, 1369–1401.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2002). Reversal of fortune: Geography and institutions in the making of the modern world income distribution. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, 1231–1294.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J. A., & Yared, P. (2005). From education to democracy? American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 95(2), 44–49.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J. A., & Yared, P. (2008). Income and democracy. American Economic Review, 98(3), 808–842.

Aghion, P., Alesina, A., Trebbi, F. (2007). Democracy, Technology, and Growth. NBER Working Paper #13180 June.

Aghion, P., Persson, T., Rouzet, D. (2012). Education and Military Rivalry. NBER Working Paper #18049, May.

Anderson, T. G., & Sorenson, B. E. (1996). GMM estimation of a stochastic volatility model: A Monte Carlo study. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 14, 328–352.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some specification tests for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58, 277–298.

Barro, R. (1996). Democracy and growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 1(1), 1–27.

Barro, R. J. (1997). The determinants of economic growth: A cross-country empirical study. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Barro, R. J. (1999). The determinants of democracy. Journal of Political Economy, 107, S158–S183.

Becker, S. O., & Woessmann, L. (2009). Was weber wrong? A human capital theory of protestant economic history. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(2), 531–596.

Benhabib, J., Corvalan, A., Spiegel, M. (2011). Reestablishing the income-democracy nexus. NBER Working Paper #16832.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143.

Bobba, M., & Coviello, D. (2007). Weak instruments and weak identification in estimating the effects of education on democracy. Economics Letters, 96(3), 301–306.

Boix, C. (2011). Democracy, development, and the international system. American Political Science Review, 105(4), 809–828.

Borner, S., Brunetti, A., & Weder, B. (1995). Political credibility and economic development. New York: Macmillan.

Bourguignon, F., & Morrisson, C. (2002). Inequality among world citizens: 1820–1992. American Economic Review, 92(4), 727–744.

Bowsher, C. G. (2002). On testing overidentifying restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Economics Letters, 77, 211–220.

Bruno, G. (2005). Approximating the bias of the LSDV estimator for dynamic unbalanced panel data models. Economics Letters, 87(3), 361–366.

Bun, Maurice J. G., & Carree, Martin A. (2005). Bias-corrected estimation in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 23(2), 200–210.

Bun, Maurice J. G., & Windmeijer, Frank. (2010). The weak instrument problem of the system GMM estimator in dynamic panel data models. Econometrics Journal, 13, 95–126.

Campante, F. R., & Chor, D. (2012). Why was the Arab world poised for revolution? Schooling, economic opportunities, and the Arab spring. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(2), 167–188.

Caselli, F., Esquivel, G., & Lefort, F. (1996). Reopening the convergence debate: A new look at cross-country growth empirics. Journal of Economic Growth, 1(3), 363–389.

Castelló-Climent, A. (2008). On the distribution of education and democracy. Journal of Development Economics, 87(2), 179–190.

Cervellati, M., Sunde, U. (2011). Democratization, Violent Social Conflicts, and Growth. IZA Discussion Papers #5643.

Fayad, G., Bates, R.H., Hoeffler, A. (2011). Income and democracy: Lipset’s law inverted. Oxcarre Working Paper #61, University of Oxford, April.

Friedman, W., Kremer, M., Miguel, E., & Thornton, R. (2011). Education as Liberation. Working paper, UC Berkeley.

Galor, O. (2005). The transition from stagnation to growth: Unified growth theory. North Holland: Handbook of Economic Growth.

Galor, O. (2011). Unified growth theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Galor, O., & Weil, D. N. (1996). The gender gap, fertility, and growth. American Economic Review, 86, 374–387.

Galor, O., & Weil, D. N. (2000). Population, technology, and growth: From the malthusian regime to the demographic transition and beyond. American Economic Review, 90, 806–828.

Glaeser, E., Campante, F. (2009). Yet Another Tale of Two Cities: Buenos Aires and Chicago. NBER Working Paper #15104, June.

Glaeser, E., Ponzetto, G., & Shleifer, A. (2007). Why does democracy need education? Journal of Economic Growth, 12(2), 77–99.

Glaeser, E., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, R., & Shleifer, A. (2004). Do institutions cause growth? Journal of Economic Growth, 9(3), 271–303.

Grosjean, P., & Senik, C. (2011). Democracy, market liberalization, and political preferences. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1), 365–381.

Gundlach, E., & Paldam, M. (2012). The democratic transition: Short-run and long-run causality between income and the gastil index. European Journal of Development Research, 24, 144–168.

Hatton, T. J., & Williamson, J. G. (2005). Global migration and the world economy: Two centuries of policy and performance. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hauk, W. R., & Wacziarg, R. (2009). A Monte Carlo study of growth regressions. Journal of Economic Growth, 14(2), 103–147.

Helliwell, J. (1994). Empirical linkages between democracy and economic growth. British Journal of Political Science, 24, 225–248.

Islam, N. (1995). Growth empirics: A panel data approach. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(4), 1127–1170.

Jefferson, T. (1779). A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge, Bill 79 in Report of the Committee of Revisors Appointed by the General Assembly of Virginia in 1776 (p. 1784). Richmond, VA: Dixon and Holt.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Ryder, H. E., & Weil, D. N. (2000). Mortality decline, human capital investment, and economic growth. Journal of Development Economics, 62(1), 1–23.

Lindert, P. (2004). Growing public. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy: Economic development and political legitimacy. American Political Science Review, 53, 69–105.

Lokshin, B. (2009). Further results on bias in dynamic unbalanced panel data models with an application to firm R &D investment. Applied Economics Letters, 16(12), 1227–1233.

Maddison, A. (2006). The world economy. Paris: OECD.

Marshall, M. G., Jaggers, K. (2008). Polity IV Project. http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm.

Milligan, K., Moretti, E., & Oreopoulos, P. (2004). Does education improve citizenship? Evidence from the United States and the United Kingdom. Journal of Public Economics, 88(9–10), 1667–1695.

Minier, J. A. (1998). Democracy and growth: Alternative approaches. Journal of Economic Growth, 3(3), 241–266.

Morrisson, C., & Murtin, F. (2009). The century of education. Journal of Human Capital, 3(1), 1–42.

Morrisson, C., & Murtin, F. (2013). The kuznets curve of education: A global perspective on education inequalities. Journal of Economic Inequality, 11(3), 283–301.

Mulligan, C. B., Gil, R., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (2004). Do democracies have different public policies than nondemocracies? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(1), 51–74.

Mulligan, C. B., Gil, R., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (2010). Social security and democracy. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 10(1), 1–27.

Murtin, F., & Viarengo, M. (2010). American education in the age of mass migrations 1870–1930. Cliometrica: Journal of Historical Economics and Econometric History, 4(2), 113–139.

Murtin, F. (2013). Long-term determinants of the demographic transition: 1870–2000. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 617–631.

Murtin, F., Wacziarg, R. (2011). The Democratic Transition. NBER Working Paper #17432, August.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica, 49, 1417–1426.

O’Rourke, K., & Williamson, J. G. (1999). Globalization and history: The evolution of a 19th century atlantic economy. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2009). Democratic capital: The nexus of political and economic change. American Economic Journal, 1(2), 88–126.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2006). Democracy and development: The devil in the details. American Economic Review, 96(2), 319–324.

Rodrik, D., Wacziarg, R. (2005). Do Democratic Transitions Produce Bad Economic Outcomes?. In American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, May 2005, (pp. 50–55).

Roodman, D. M. (2009a). A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 71(1), 135–158.

Roodman, D. M. (2009b). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136.

Schumpeter, J. (1942). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. New York: Penguin Classics.

Tavares, J., & Wacziarg, R. (2001). How democracy affects growth? European Economic Review, 45(8), 1341–1379.

Tinbergen, J. (1975). Income distribution: Analysis and policies. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Tocqueville, A. (1835). Democracy in America. New York: Penguin Classics.

Treisman, D. (2011). Income, Democracy and the Cunning of Reason. NBER Working Paper #17132.

Weber, Max (1904/05). Die protestantische Ethik und der, Geist“ des Kapitalismus. Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik 20: 1–54 and 21: 1–110. Reprinted in: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Religionssoziologie, 1920: 17–206.

Windmeijer, F. (2005). A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. Journal of Econometrics, 126, 25–51.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maurice Bun, Anke Hoeffler, Peter Lindert, Casey Mulligan, three anonymous referees and the editor for helpful comments. This paper does not express the official views of the OECD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murtin, F., Wacziarg, R. The democratic transition. J Econ Growth 19, 141–181 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-013-9100-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-013-9100-6