Abstract

The goal of this study is to validate a new, continuous, noninvasive stroke volume (SV) method, known as transbrachial electrical bioimpedance velocimetry (TBEV). TBEV SV was compared to SV obtained by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) in normal humans devoid of clinically apparent heart disease. Thirty-two (32) volunteers were enrolled in the study. Each subject was evaluated by echocardiography to assure that no aortic or mitral valve disease was present. Subsequently, each subject underwent electrical interrogation of the brachial artery by means of a high frequency, low amplitude alternating current. A first TBEV SV estimate was obtained. Immediately after the initial TBEV study, subjects underwent cMRI, using steady-state precession imaging to obtain a volumetric estimate of SV. Following cMRI, the TBEV SV study was repeated. Comparing the cMRI-derived SV to that of TBEV, the two TBEV estimates were averaged and compared to the cMRI standard. CO was computed as the product of SV and heart rate. Statistical methods consisted of Bland–Altman and linear regression analysis. TBEV SV and CO estimates were obtained in 30 of the 32 subjects enrolled. Bland–Altman analysis of pre- and post-cMRI TBEV SV showed a mean bias of 2.87 % (2.05 mL), precision of 13.59 % (11.99 mL) and 95 % limits of agreement (LOA) of +29.51 % (25.55 mL) and −23.77 % (−21.45 mL). Regression analysis for pre- and post-cMRI TBEV SV values yielded y = 0.76x + 25.1 and r2 = 0.71 (r = 0.84). Bland–Altman analysis comparing cMRI SV with averaged TBEV SV showed a mean bias of −1.56 % (−1.53 mL), precision of 13.47 % (12.84 mL), 95 % LOA of +24.85 % (+23.64 mL) and −27.97 % (−26.7 mL) and percent error = 26.2 %. For correlation analysis, the regression equation was y = 0.82x + 19.1 and correlation coefficient r2 = 0.61 (r = 0.78). Bland–Altman analysis of averaged pre- and post-cMRI TBEV CO versus cMRI CO yielded a mean bias of 5.01 % (0.32 L min−1), precision of 12.85 % (0.77 L min−1), 95 % LOA of +30.20 % (+0.1.83 L min−1) and −20.7 % (−1.19 L min−1) and percent error = 24.8 %. Regression analysis yielded y = 0.92x + 0.78, correlation coefficient r2 = 0.74 (r = 0.86). TBEV is a novel, noninvasive method, which provides satisfactory estimates of SV and CO in normal humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Ejection of SV is the primary mechanical function of the heart and, in response to metabolic oxygen requirements SV is modulated by contractility, loading conditions, and heart rate to produce the requisite cardiac output (CO). CO is the ultimate expression of cardiovascular performance and, because it is the cornerstone of oxygen transport goal-oriented therapy, its assessment and optimization in critically-ill humans is of paramount importance [1]. Thermodilution cardiac output (TDCO) is currently the gold standard method for CO determination in the critically ill [2, 3]. However, with the virtual demise of the pulmonary artery catheter as a diagnostic tool for estimating left ventricular preload [4, 5], its justification and indications for TDCO determination are becoming slimmer and more stringent [6, 7]. Because of its invasiveness and potential complications, a search for minimally invasive or noninvasive alternatives for TDCO is ongoing [8–10].

What is readily apparent from review of the literature is the paucity of accurate, simple, technician-independent, “hands-off”, continuous, noninvasive CO methods, which do not require external calibration [3, 8–10]. Transthoracic electrical bioimpedance cardiography, otherwise known as impedance cardiography (ICG), is a technology that fulfills all the requirements for an ideal CO method, except for its lack of consistent accuracy [3, 8–11]. Because of the generally poor performance of the transthoracic technique in sick humans [11, 12], and especially those with excess intrathoracic extravascular lung water [13, 14], the technology has been deemed of marginal usefulness in the care of the critically ill [11].

This study in normal humans concerns the validation of a new noninvasive, velocimetric-based, pulsatile SV technique, known as transbrachial electrical bioimpedance velocimetry (TBEV) [15]. As compared to ICG implemented transthoracically, TBEV is, in theory and method, an ICG equivalent, but operationally signal acquisition is obtained from the upper arm. For this validation study, TBEV SV is compared with that obtained from cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI), which is considered the absolute “gold-standard” for determination of ventricular volumes [16, 17].

2 Methods

2.1 Study population

Thirty-two (32) volunteer adult subjects were recruited for the study. By history, physical examination, electrocardiography, echocardiography, and magnetic resonance imaging, the subjects showed no demonstrable evidence of heart disease. Since cMRI is considered the absolute gold standard for measurement of ventricular volumes [16, 17], SV obtained from that technique was compared to SV determined by TBEV [15]. In order to obtain a wide spectrum of SV and CO, subjects were recruited with a broad range of heights, weights, and body mass indices (BMI). Body surface area (BSA) for each subject was calculated using the Mosteller equation [18] (Table 1). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, as well as Aspire Institutional Review Board, San Diego, and all subjects provided written and oral informed consent.

2.2 Echocardiography protocol

All subjects underwent echocardiography, including color, pulsed, and continuous wave Doppler. Studies were performed using a commercially available echograph (iE33, Philips Medical, Andover, MA) with a broadband 2.0–3.5 MHz phased-array transducer to assess the presence of mitral and/or aortic valve disease. This was to ensure that all participants had structurally normal hearts. Subjects were positioned in the left lateral decubitus position and standard images were obtained from the parasternal and apical windows in accordance with current guidelines [19]. Data were acquired and stored in digital format, then analyzed offline using a separate workstation.

2.3 MRI protocol

Subjects were scanned on a Signa 1.5T HDx scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). After localizing images were obtained, a short axis stack of images through the entire left ventricle was acquired during end-expiration, using steady-state free precession (SSFP) imaging with a slice thickness of 8 mm, spacing of 2 mm, in-plane grid of 224 × 224, and acceleration factor of 1.5. The number of views per segment was adjusted as needed to yield a temporal resolution of 50 ms or less, and the field of view was adjusted as needed, based upon each subject’s habitus. HR was recorded for each acquisition and the average HR during imaging was computed. Each cMRI scan was completed in approximately 1 (one) hour.

2.4 cMRI image analysis

MRI images were analyzed offline, using an Advantage Workstation with ReportCard 4.0 (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). End-systolic and end-diastolic frames were manually identified by visual inspection of the largest and smallest volume. Then, for each slice, the endocardium was manually traced at these two time points, including the papillary muscles with the contours, and left ventricular volume was subsequently calculated using the modified Simpson’s method [16]. SV was determined as the difference between the end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes. CO was then calculated as the product of measured SV and the average recorded HR. Stroke index (SI) and cardiac index (CI) were calculated as the SV and CO divided by BSA.

2.5 Transbrachial electrical (bioimpedance) velocimetry (TBEV)

2.5.1 TBEV device

The TBEV system is a wearable, battery-powered, four-lead impedance cardiograph. It is worn on the upper arm and is held in place only by custom adhesive electrode patches (Vermed®, Inc, Bellows Falls, VT, USA) (Fig. 1a). The system consists of two electrical housings connected by an electric cable: (1) a proximal assembly that is attached to a dual-element electrode, which is placed below the clavicle, proximal to the humeral head and axilla; and (2) a dual-element distal assembly which is attached to the anteromedial surface of the upper arm, proximal to the antecubital fossa (Fig. 1a, b). Using this electrode arrangement for interrogation of the brachial artery, an alternating current (ac, I, A) field is applied along and within the long axis of the upper arm. As a result of passing ac through an electrical impedance Z (ohm, Ω) (i.e. resistance to ac), a potential difference (voltage, U) within the current field is obtained. This is an expression of Ohm’s Law applied to biological tissues (i.e. IZ = U). The proximal assembly houses the upper voltage sensor and current driver, and the distal assembly houses the electronic circuit board into which the lower voltage sensor and current driver are integrated [15]. Figure 1b is a photograph of a human volunteer wearing the TBEV montage.

a A pictorial circuit diagram from which SV and CO are obtained. Shown are the upper and lower housings for the electrode patches on the arm. AC is injected via the outer electrodes and voltage electrodes are shown as the inner electrodes. Voltage is demodulated, amplified and filtered to obtain Z0 and ∆Z(t), which then undergo analog to digital (A to D) conversion. Electronic differentiation of ∆Z(t) yields dZ/dt. dZ/dtmax/Z0 undergoes square root transformation. TSF (systolic flow time) is multiplied by the volume conductor (VC) and ([dZ/dtmax/Z0])0.5 to obtain stroke volume (SV). SV is multiplied by heart rate (HR) to obtain cardiac output (CO). Details found in text. b Photograph of volunteer with ECG patch electrodes on upper chest, TBEV electrode housing on the upper brachium, and wiring to an electrode housing just proximal to the antecubital fossa. The impedance signals are relayed to a signal processor shown on the wrist. Also shown is a pulse oximeter on thumb

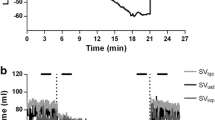

The TBEV analog circuit emits a constant magnitude, small amplitude 70 kHz, 4 mA RMS ac source, driving the signal through a segment of the upper arm through the current driver electrodes (Fig. 1a). The 70 kHz carrier signals from each voltage sensor first pass through identical filters (25 kHz low pass and 20 kHz high pass) and amplification stages. The signals are then differentially amplified and passed to an amplitude demodulation circuit. The high and low frequency components of the total transthoracic impedance (Z(t)) are then separated into two major components; (1) ∆Z, further comprising (a), a sinusoidal respiratory component, which is filtered out, and (b), a superimposed pulsatile time-variable ac cardiodynamic component (∆Z(t)), and (2) Z0, a quasi-static transbrachial base impedance, respectively. Further signal processing of ΔZ(t) entails finding the peak value of the first time-derivative of dZ/dt (i.e. dZ/dtmax, Ω s−2), and systolic flow time (TSF, s) from fiducial landmarks on the dZ/dt waveform [15, 20] (Fig. 2a, b). Finally, to obtain ohmic mean velocity, the quotient of dZ/dtmax and Z0 undergo square root transformation. To obtain SV, a volumetric constant (VC, mL) is calculated from total body weight (W, kg), whereupon the variables are placed into the SV equation (vide infra).

a In the upper tracing is shown a dZ/dt waveform from the thorax. In the lower tracing is shown a dZ/dt tracing from the brachium. Note that for the transthoracic waveform, the end of ejection (flow) is the nadir after the first zero crossing after point C, dZ/dtmax. In the lower tracing is shown a dZ/dt waveform obtained from the brachium. Note that the end of flow is the second zero crossing after point C, dZ/dtmax. The waveforms were obtained simultaneously, but, because of the transmission delay, they were aligned synchronously in time to illustrate the same TSF. b The transbrachial impedance pulse variation ∆Z (upper tracing) and its differentiated first time-derivative dZ/dt (lower tracing). In both tracings the onset of flow is marked as point B, the maximum forward slope of ∆Z and peak first time-derivative dZ/dtmax as point C, and termination of flow as point X [20]. The temporal interval from B to X is systolic flow time TSF

The TBEV analog electronics were identical across all subjects. The waveforms for subjects 1 through 13 were digitized in real-time using a BIOPAC UIM100C system (BIOPAC, Goleta, CA, USA) and then stored on a laptop PC for later analysis. All waveforms were sampled at 16-bit resolution and 500 Hz. In addition, A BIOPAC ECG100C module was used to collect a single ECG lead II waveform for determining HR and gating of dZ/dt. Subjects 14 though 32 were digitized using an integrated digital sub-system on the TBEV circuit board (Sotera Wireless, San Diego, CA, 92121, USA). With regard to the two prototype impedance platforms, they were operationally identical for signal acquisition and data processing.

2.5.2 Assumptions of the method [15, 20, 21]

It is assumed that;

-

1.

Schematically, the brachium can be considered a thin-walled cylinder, encasing an aggregate of adynamic tissues of high impedance, which, in turn, encircle a single dynamic blood-filled vascular conduit of low impedance.

-

2.

When an ac field is applied longitudinally over a segment of the brachium, the brachium can be considered, bio-electrically, a parallel conduction curcuit, connecting (1) a poorly conductive static tissue impedance, Zt, (2) a highly conductive blood resistance (Rb, Zb), and (3) the smallest volume, but highest conductivity impedance, reflecting the quasi-static interstitial tissue water, (Zw), varying with tissue hydration. The parallel (║) reciprocal sum, Z −1t + Z −1b + Z −1w , constitutes the quasi-static base impedance, Z0. When the static and quasi-static tissue impedances are added in parallel with the time-dependent, dynamic pulsatile component of the blood resistance (∆Rb(t) ≡ ∆Zb(t)), the total transbrachial impedance, Z(t) results. As per Ohm’s Law (vide supra); when an ac field is uniformly applied longitudinally across both the static and dynamic impedances, a potential difference between the current injecting electrodes produces the parallel connection of a static and dynamic voltage; U −10 and ∆Ub(t)−1, respectively. In concise bio-electric mathematical language,

$$I(t) \cdot \left[ {\left( {\left\| {Z_{t} } \right\|Z_{b} \left\| {Z_{w} } \right.} \right)\left\| {\Delta Z_{b} (t)} \right.} \right] = \left. {U_{0} } \right\|\Delta U_{b} (t)$$(1)A schematic electronic circuit diagram reflecting Eq. 1 is given as follows (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 The transbrachial impedance (Z(t)) comprises four elements. The three static elements include the impedance path through the tissue (Zt), the blood (Zb), and the interstitial water (Zw). The parallel connection of these static impedances constitutes the transbrachial base impedance, Z0. The parallel connection between Z0 and the pulsatile component, ∆Zb(t), constitutes the total impedance of the brachium (Z(t)). Shown is the current input (I(t)) and time variable voltage output (U(t))

-

3.

The brachial artery is poorly compliant and mechanically resembles a rigid muscular tube, rendering volume changes trivial. Thus,

-

4.

All cardiogenically-induced impedance changes (∆Zb(t)) are due solely to blood velocity-induced resistivity changes (∆ρb(t), Ω cm s−1)

-

5.

The velocity-induced change in blood resistivity is due to the changing orientation of the bi-concave, disc-shaped erythrocytes from random orientation in end-diastole (state of lowest conductivity) to parallel orientation along their long axis of symmetry (state of highest conductivity) in the rapid ejection phase of systole

-

6.

Transbrachial ∆Zb(t) (Ω s−1) is an ohmic analog of brachial artery blood velocity (cm s−1), which implies that its peak first time-derivative, dZ/dtmax (Ω s−2), is an acceleration analog

-

7.

Transbrachial dZ/dtmax (Ω s−2) peaks precisely with brachial artery peak blood acceleration (cm s−2)

-

8.

Peak brachial artery acceleration (cm s−2) is directly proportional to the magnitude and change of magnitude of peak aortic blood acceleration (cm s−2)

-

9.

Peak transthoracic dZ/dt (dZ/dtmax) is directly proportional to the magnitude and change in magnitude of peak aortic blood acceleration

-

10.

Transbrachial dZ/dtmax is directly proportional to the magnitude and change in magnitude of transthoracic dZ/dtmax and thus,

-

11.

Transbrachial dZ/dtmax is directly proportional to the magnitude and changes in magnitude of peak aortic blood acceleration.

-

12.

To obtain dimensionless ohmic mean velocity (s−1), square root transformation of dZ/dtmaz/Z0 is necessary

-

13.

A constant ratio of 2:1 exists between the magnitudes of transthoracic ohmic mean velocity and transbrachial ohmic mean velocity, respectively. Thus, reciprocally,

-

14.

A constant ratio of 1:2 exists between the magnitudes of the transthoracic and transbrachial VC, respectively

-

15.

The magnitude of the transthoracic constant of proportionality, otherwise known as the volume conductor (VC, mL) is equivalent to the global end-diastolic volume (GEDV, mL)

2.5.3 TBEV data collection protocol

Two 5-min sessions of TBEV waveforms were collected. The first was collected immediately prior to the cMRI, and the second immediately following the cMRI. The subjects remained supine from the start of the first measurement, through the cMRI, and until the end of the second TBEV measurement. The subjects were instructed to remain silent and still for the duration of the measurements.

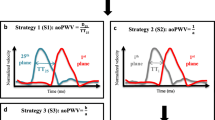

2.5.4 TBEV signal processing

First, a 30 s interval out of each 5 min period was selected for analysis. By default, this period was 150–180 s, but if any significant artifact was present upon operator inspection, then a different 30-s period was selected manually. To find a mean value over the relevant time interval, signal averaging was implemented. This was the only manual intervention in the analysis. TBEV SV was then calculated according to the equation of Bernstein et al. [15].

-

VC = volume conductor (mL) = 32 × W1.02, where W = total body weight (kg)

-

dZ/dtmax = peak time rate of change of the transbrachial impedance pulse variation (Ω s−2)

-

Z0 = quasi-static transbrachial base impedance (Ω)

-

TSF = systolic flow time (s) ≡ left ventricular ejection time (s)

-

\(\sqrt {\frac{{dZ/dt_{\hbox{max} } }}{{Z_{0} }}}\) = ohmic mean velocity (s−1)

Rationale for a mass-based VC, the square root transformation, and the unit assignment of Ω s−2 for dZ/dtmax are discussed extensively elsewhere [15, 20, 21].

2.5.5 Statistical analysis

For each group of subjects, to assess reproducibility and accuracy, we employed Bland–Altman method and calculated mean bias, standard deviations (SD), precision, limits of agreement (LOA), and percent error for absolute values of the continuous parameters studied [22]. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r2) was calculated and used to assess the closeness of association between continuous variables. For statistical analysis we used R version 3.0.0 (2013-04-03), Copyright (C) 2013, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

3 Results

3.1 Demographics and echocardiography

The study population demographics are summarized in Table 1. There were 24 males, the mean age was 41.5 ± 12.5 years, and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 26 ± 4.4 kg m−2 and ranged from 19 to 35 kg m−2. All subjects were in normal sinus rhythm. Upon Doppler echocardiographic interrogation, all subjects had trace or no mitral regurgitation. One subject had mild aortic regurgitation; all other subjects had trace or no aortic regurgitation.

3.2 cMRI

High quality cMRI images were obtained in all subjects (n = 32) and displayed well-defined endocardial borders that allowed calculation of left ventricular (LV) SV and CO. Values for these and other cMRI parameters are listed in Table 1. The average ejection fraction was 62.2 ± 4.6 %, and the average CO was 6.08 ± 1.3 L min−1, with a mean cardiac index of 3.00 ± 0.41 L min−1 m−2.

3.3 TBEV

The TBEV units functioned as intended, with high quality waveform and digital data obtained in all but three subjects. In two subjects, who were evaluated the same day, data acquisition equipment malfunction occurred, and hence no useable TBEV data was obtained. In a third subject, the pre-MRI TBEV data was accidentally over-written due to operator error and therefore was unavailable. Hence, full datasets were obtained in 29 subjects, and for a 30th subject, only the post-MRI TBEV data was obtained. In a fourth subject, the disparity between pre- and post-cMRI SV was 33 mL (88.73–55.78 mL), which translates to Bland–Altman percent difference of 45.7 %. The corresponding cMRI SV was 102.2 mL. This disparity was probably due to a spurious value of Z0 for the post TBEV measurement. Pre-TBEV Z0 was 60 versus 100 Ω for the post MRI Z0. This is impossible, because there was no change in brachial tissue extra-cellular water over the cMRI interval. The disparity, no doubt, was due to a defective electrode or faulty adhesion of the electrode-to-skin interface. Despite this obvious outlier, the paired estimates were included in statistical analysis. Raw TBEV input and output variables are shown in Table 2. The results demonstrate that, for pre- and post-cMRI, the mean values for TSF, Z0, SV, HR and CO are virtually unchanged for males and females. The largest mean difference from pre- to post-cMRI occurred in dZ/dtmax for both males (9 %) and females (6 %). Also of interest, the mean value of the magnitude of the male VC is approximately 50 % larger than the female counterpart. If the mean value of the magnitude of ohmic mean velocity is calculated from the data (see Eq. 2), female values are about 18 % higher than the male cohort. In conjunction with a 3 % longer TFS in females, the difference between males and females renders SV in males approximately 25 to 30 % higher. A total of 30 subjects were used in statistical analysis (n = 30).

3.4 Bland–Altman: mean bias, precision, and limits of agreement (LOA)

Mean bias, precision, mean bias ± 1.96 × SD (LOA), and percent error for TBEV SV versus cMRI SV and TBEV CO versus cMRI CO are shown in Table 3. Of note in Table 3 are the small biases, similar levels of precision, and LOA for the three paired comparisons. Percent error for TBEV SV versus cMRI SV and TBEV CO versus cMRI CO are virtually identical, being 26.2 and 24.8 %, respectively. Since cMRI SV is essentially without precision error, the disparity in measurements of SV and CO between the methods can be attributed almost entirely to the precision errors of TBEV. Bland–Altman methodology was used to assess comparisons of TBEV pre- versus post-cMRI SV, averaged TBEV SV versus cMRI SV and averaged TBEV CO versus cMRI CO. This analysis also assumes that true SV remained unchanged over the cMRI interval. Table 3 and Fig. 4a show results of Bland–Altman analysis for TBEV CO versus cMRI CO.

3.5 Linear regression analysis

The regression coefficients, y-intercepts, and correlation coefficients for three paired comparisons are presented in Table 4. It is interesting to note that, for TBEV SV versus cMRI SV is the lowest of the three comparisons with a regression coefficient of 0.82 and correlation coefficient of r2 = 0.61 (r = 0.78). The regression coefficient in Fig. 4b is a scatterplot of TBEV CO versus cMRI CO, showing a correlation coefficient r2 = 0.74 (r = 0.86), a regression coefficient close to unity (i.e. 0.92), and a y-intercept less than 1 (one) L min−1 (i.e. 0.78 L min−1). This suggests little systematic bias of CO between the methods. Due to the absolute precision of cMRI SV, the scatter around the regression line represents random errors of the TBEV method.

4 Discussion

4.1 Recent studies and historical aspects

Results obtained in this study are similar to our previous study in normals, comparing TBEV SV to Doppler/echo-derived SV [15, 20]. By Bland–Altman method, the mean bias was −4.0 % (2.5 mL), precision of 14.7 % (11.9 mL), and limits of agreement of +33.4 and −25.4 %. Contrary to the sequence of method comparisons in this study, which were spaced-apart temporally, in our prior study Doppler/echo and TBEV SV measurements were obtained simultaneously.

Transbrachial SV determination is not without historical precedent. It is interesting to note that, in Nyboer’s seminal article in 1950, he used a 4 band-electrode montage on the forearm to obtain plethysmographic (volumetric) impedance measurements [23]. That article also presented the original equations that evolved into those used in transthoracic ICG [21]. Using a similar electrode array to ours, a more recent study, assessing cardiogenically-induced bioimpedance changes of the forearm, has shown close correspondence between SV changes and percent changes obtained from the aortic root and the changes and percent changes in both the maximum amplitude of the impedance pulse variation ∆Zmax (r = 0.86 and r = 0.84, respectively) and the area beneath the ∆Z waveform envelope (r = 0.78 and r = 0.78, respectively) [24].

4.2 Strength and advantages of TBEV

First, in contrast to the transthoracic approach, there are virtually no potentially confounding or competing vessel resistivities or volume changes in the upper arm. The sole vessel of any magnitude is the brachial artery, which is probably the only major source providing a waveform for signal processing. Unlike transthoracic dZ/dt, which has multiple signal sources and both a volumetric and blood velocity-induced resistivity component [25], the brachial artery is sufficiently stiff to yield a signal whose origin is purely reflective of axial blood flow [15]. Secondly, unlike the transthoracic method, which is highly susceptible to excess extravascular lung water [13, 14], brachial measurements are taken distant from the lung and apart from the bony thorax. As a consequence of the upper arm being detached from the thorax, the wide respiratory-induced oscillations of baseline impedance (Z0), seen in the transthoracic approach, are much attenuated in the upper arm. As concerns signal processing, this improves detection of baseline impedance Z0, leading to fewer morphologic distortions of ∆Zb(t), thus resulting in less need for adaptive filtering.

4.3 Limitations and errors of the method and study design

The results from this study suggest that the theory and equations are, at least in the first approximation, correct. However, it must be remembered that this study was conducted with healthy volunteers who were apparently free of heart disease. Potential mechanical limitations of the method entail atherosclerotic obstructive disease of the subclavian and axillo-brachial circulations, namely subclavian and axillo-brachial stenosis [26]. Stenosis induces high velocity jets, blood turbulence, and disturbed laminar flow, precluding accurate SV determination [27]. Hemodynamically, abnormal ejection patterns can potentially cause distortion of the brachial artery waveform envelope, thereby preventing accurate signal processing [27, 28]. Clearly, random errors in measurement of dZ/dtmax, Z0, and systolic flow time (TSF) can degrade the accuracy of the method. Operationally, defective electrodes will yield invalid results.

Two serious design flaws in our study protocol entailed; (1) the non-simultaneity of the TBEV and cMRI measurements and (2) the lack of a gold-standard continuous method by which to assess TBEV’s accuracy and tracking/trending capability over a wide range of hemodynamic perturbations. In this regard, we were unable to completely verify assumptions 8 through 11 (Sect. 2.5.2). Concerning lack of simultaneity of the TBEV measurements, the following is relevant; since all metallic objects of ferric origin are contraindicated while undergoing cMRI, the TBEV cables, electrodes, and wrist-worn device were obligatorily disconnected and then reconnected. It was originally assumed that TBEV SV would not change during the cMRI interval, and if it did, only minimally. Judging by the precision and LOA of the two TBEV comparison measurements (Table 3), it is difficult to determine whether SV actually changed, or was simply a function of the imprecision of the method. Since the two TBEV measurements were separated by about an hour, a combination of precision error and actual change in SV probably occurred. It is thus speculated that, had the comparison between simultaneous measurements of TBEV SV versus cMRI SV been technically possible, the precision and accuracy may have been appreciably better. Again, regarding the non-simultaneity of TBEV versus cMRI measurements, it was our objective to compare precision and accuracy with an absolute measurement of SV. Clearly, it was an erroneous assumption that the two TBEV measurements would remain constant over the cMRI interval, or that the average of the two measurements would represent the time-averaged cMRI SV over the scanning period.

As concerns clinical efficacy, it is not known how changes in loading conditions or administration of vasodilators, vasoconstrictors or inotropic medications will affect the accuracy of the TBEV measurement. On this very issue, Chemla et al. [29, 31] found that, unlike peak velocity, brachial artery peak acceleration was unaffected by downstream vasoactivity and only by positive or negative β1 inotropic and chronotropic medications directly affecting the adrenoceptors of the myocardium. This suggests that ohmic peak brachial artery acceleration (i.e. dZ/dtmax) may respond similarly.

Other limitations of the study include a cohort mainly of males (22/8) and the inability to obtain TBEV waveforms in the presence of arm or body motion or complex dysrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation. While the implementation of two prototype impedance platforms might be perceived as a limitation, they were operationally identical for signal acquisition and data processing.

4.4 Assumptions and inherent errors of the method

4.4.1 A constant ratio of 2:1 exists between the magnitudes of transthoracic and transbrachial ohmic mean velocity

A basic assumption of the method assumes that using transthoracic dZ/dtmax and the parent equation of Eq. 1 [30], results in valid approximations of SV. As described in prior publications, the accuracy and precision of TBEV SV depends upon a monotonically fixed ratio between the magnitudes and changes in magnitude of peak aortic and peak brachial artery blood acceleration (dv/dtmax, cm s−2; dQ/dtmax, mL s−2) [15, 20, 31]. Since transthoracic and transbrachial dZ/dtmax are considered ohmic analogs of peak aortic and peak brachial artery blood acceleration, respectively [15, 31], it was hypothesized that SV could be obtained from the brachial artery using the skeleton of Eq. 1 (vide supra) [30]. Pursuant to that hypothesis, it was found that the ratio of transthoracic to transbrachial ohmic mean velocity ([dZ/dtmax·Z −10 ]0.5, s−1) was approximately 2 to 1 (i.e. 2:1) [15, 20]. Comparing the latter to the former, we found a mean bias of −46.4 % (~50 %), a transthoracic to transbrachial mean ratio of 2.16:1, and percent deviation from 2:1 of 8 %. In 36 of the 38 study subjects (94.7 %), paired data points were equal to or less than 15 % from the mean [20]. Thus, at the operational level, and as an inherent pre-requisite assumption of the method, the direct proportionality and a constant 2:1 ratio between transthoracic and transbrachial ohmic mean velocity may not exist in an unknown patient population. These ratios may even change in the same individual over time and may account for some portion of the precision error between pre- and post-cMRI TBEV SV measurements (Table 3). This can lead to an unpredictable degree of uncontrollable under or overestimation of transbrachial ohmic mean velocity, and thus SV. Thus, assumption 13 (Sect. 2.5.2) is only an approximation.

4.4.2 An allometric relationship between body weight and GEDV is a constant

Since the ratio of transthoracic to transbrachial ohmic mean velocity is approximately 2:1, and in an abstraction of the equation of continuity for conservation of mass flow, the ratio of the magnitude of transthoracic to the transbrachial VC was set empirically and reciprocally at 1:2. Theoretically, the physical embodiment of the transthoracic VC was estimated to approximate the GEDV. Thus, the allometric relationship of body weight to GEDV was empirically approximated as 16W1.02 (~17 mL kg−1) [30].Footnote 1 For allometrics, the relationship of body weight to GEDV is given as aMb, where “a” is a constant of proportionality, M is patient body mass (kg), and “b” is an exponential constant describing linearity or non-linearity [32]. The exponential constant, 1.02, implies a linear relationship between body weight and GEDV. Conversion of body weight directly to blood volume is valid, because the density of blood (ρ, g mL−1) is 1.05–1.06. When empirically derived GEDV is multiplied by a mean value of 1.25, the generally accepted mean correction factor for conversion to intrathoracic blood volume (ITBV) (range 1.21–1.45) [33], 21.25 mL kg−1 is the result. This empirically-derived calculated value was verified experimentally by Moller et al. [34] as the indexed mean ITBV for patients without cirrhosis. Further interpretation of their data for these patients yielded a pooled SD of approximately ±4.7 mL kg−1, corresponding to ±22 %. By mathematical coupling, this percent error is fully transferrable to the GEDV. Corroborating the aforementioned studies, data provided by Metzelder et al. [35] show that, for a mean control ITBV of 1638 mL and a mean weight for patients of 74 kg, the mean calculated indexed ITBV was 22.14 mL kg−1. When this value is divided by 1.25 to obtain GEDV, the result is 17.7 mL kg−1. This value is 4.7 % greater than using the transthoracic coefficient and exponent, 161.02 (i.e. 16.9 mL kg−1). While the measured mean indexed values for the ITBV are well described by the allometric expression, 16W1.02 multiplied by 1.25 [33], the rather substantial standard deviations, especially those reported by Moller et al. [34], contribute to the error of the fixed-value transbrachial coefficient and exponent, 321.02 mL kg−1. As is true for assumption 13 (Sect. 2.5.2), assumption 15 is an approximation.

4.4.3 Transbrachial dZ/dtmax is an ohmic analog of peak brachial artery acceleration

Transthoracically, the assumption that dZ/dtmax peaks synchronously with the I wave of the acceleration ballistocardiogram (aBCG) [21, 30], in the time-domain, has recently been challenged. Luchitskaya et al. and Ulbrich et al. have shown experimentally that, dZ/dtmax peaks ~23–28 ms after peak acceleration of blood flow [36, 37], but before peak aortic blood flow (dV/dtmax). This finding would appear to somewhat question the acceleratory nature of transthoracic dZ/dtmax and necessity for the square root acceleration step-down transformation to obtain ohmic mean velocity (Sect. 2.5.2 assumptions 7–12). Operationally, however, when implementing the transthoracic technique, the parent equation of Eq. 2 has been validated extensively according to assumption 12 (Sect. 2.5.2) [38–43]. Experimentally, it has been definitively demonstrated that an equation using square root transformation of dZ/dtmax/Z0 provides better agreement and correlation with TDCO than equations which assume a volumetric origin for dZ/dtmax [30]. Despite the findings disputing the peak acceleratory origin of transthoracic dZ/dtmax [36, 37], pictorial and analytical evidence provided by Bernstein [21] clearly indicates that dZ/dtmax peaks synchronously with peak aortic blood acceleration and I wave of the aBCG. Thus, although transthoracic dZ/dtmax may not peak precisely with peak acceleration, but closely within the time domain, it can be treated as such. Moreover, with respect to the transbrachial method, it has been definitively demonstrated that peak Doppler brachial artery blood acceleration and peak brachial artery ohmic acceleration reach their magnitudes synchronously in the time domain [15, figure 8c, d]. This appears to validate assumption 7 (Sect. 2.5.2).

It should be fully appreciated that the TBEV technique may not provide credible SV or CO values in the presence of critical illness. However, this and our previous study [15], both showing proof of concept, serve as evidence that SV can be obtained by TBEV technique in the ideal homeostatic hemodynamic state. Future validation studies in sick humans, comparing TBEV to another validated continuous SV/CO technique, such as in the studies by Metzelder et al. [35] and Lorne et al. [44], will determine the viability of TBEV in clinical medicine.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we present a comparison of SV and CO obtained via electrical interrogation of the brachial artery by the TBEV technique with SV and CO obtained by cMRI in normals. Despite its potential sources of error, we found that TBEV resulted in satisfactory reproducibility and agreement with cMRI. While not interchangeable with cMRI, based on existing criteria for the reproducibility of pulmonary artery TDCO [45, 46] and its LOA, [46] the precision and accuracy of TBEV CO obtained in this study may be clinically acceptable if maintained in the critically ill.

References

Pinsky MR. Hemodynamic evaluation and monitoring in the ICU. Chest. 2007;132:2020–9.

Reuter DA, Huang C, Edrich T, Sherman SK, Eltzschig HK. Cardiac output monitoring using indicator dilution techniques: basics, limitations, and perspectives. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:799–811.

Lee AJ, Cohn JH, Ranasinghe JS. Cardiac output assessed by invasive and minimally invasive techniques. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:475151. doi:10.1155/2011/475151.

Della Rocca G, Costa GM, Coccia C, Pompei L, Di Marco P, Pietropaoli P. Preload index: pulmonary artery occlusion pressure versus intrathoracic blood volume monitoring during lung transplantation. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:835–43.

Kumar A, Anel R, Bunnell E, Habet K, Zanotti S, Marshall S, Neumann A, Ali A, Cheang M, Kavinsky C, Parrillo JE. Pulmonary artery occlusion pressure and central venous pressure fail to predict ventricular filling volume, cardiac performance, or the response to volume infusion in normal subjects. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:691–9.

Chatterjee K. The Swan-Ganz catheters: past, present, and future: a viewpoint. Circulation. 2009;119:147–52.

Marik PE. Obituary: pulmonary artery catheter 1970 to 2013. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3:38.

Peyton PJ, Chong SW. Minimally invasive measurement of cardiac output during surgery and critical care: a meta-analysis of accuracy and precision. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1220–35.

Truijen J, van Lieshout JJ, Wesselink WA, Westerhof BE. Noninvasive continuous hemodynamic monitoring. J Clin Monit Comput. 2012;26:267–78.

Marik PE. Noninvasive cardiac output monitors: a state-of-the-art review. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013;27:121–34.

Kamath SA, Drazner MH, Tasissa G, Rogers JG, Stevenson LM, Yancy CW. Correlation of impedance cardiography with invasive hemodynamic measurements in patients with advanced heart failure: bioimpedance cardiography (BIG) substudy of the ESCAPE Trial. Am Heart J. 2009;158:217–23.

Raaijmakers E, Faes TJ, Scholten RJ, Goovaerts HG, Heethaar RM. A meta-analysis of three decades of validating thoracic impedance cardiography. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1203–13.

Peng ZY, Critchley LA, Fok BS. An investigation to show the effect of lung fluid on impedance cardiac output in the anesthetized dog. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:458–64.

Critchley LA, Calcroft RM, Tan PY, Kew J, Critchley JA. The effect of lung injury and excessive lung fluid, on impedance cardiac output measurements, in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:679–85.

Bernstein DP, Henry IC, Banet MJ, Dittrich T. Stroke volume obtained by electrical interrogation of the brachial artery: transbrachial electrical bioimpedance velocimetry. Physiol Meas. 2012;33:629–49.

LaGerche A, Claessen G, Van de Bruaene A, Pattyn N, Van Cleemput J, Gewillig M, Bogaert J, Dymarkowski S, Claus P, Heidbuchel H. Cardiac MRI: a new gold standard for ventricular volume quantification during high-intensity exercise. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:329–38.

Pennell DJ. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2010;121:692–705.

Mosteller RD. Simplified calculation of body-surface area. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1098.

Quinones MA, Otto CM, Stoddard M, Waggoner A, Zoghbi WA. Recommendations for quantification of Doppler echocardiography. a report from the Doppler Quantification Task Force of the nomenclature and standards committee of the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:167–84.

Henry IC, Bernstein DP, Banet MJ. Stroke volume obtained from the brachial artery using transbrachial bioimpedance velocimetry. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2012;2012:142–5.

Bernstein DP. Impedance cardiography: pulsatile blood flow and the biophysical and electrodynamic basis for the stroke volume equations. J Electr Bioimp. 2010;1:2–7.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10.

Nyboer J. Electrical impedance plethysmography. A physical and physiological approach to peripheral vascular study. Circulation. 1950;2:811–21.

Wang JJ, Wang PW, Liu CP, Lin SK, Hu WC, Dao T. Evaluation of changes in cardiac output from the electrical impedance of the forearm. Physiol Meas. 2007;28:989–99.

Wang L, Patterson R. Multiple sources of the impedance cardiogram based on 3-D finite difference human thorax models. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1995;42:141–48.

Ochoa VM, Yeghiazarians Y. Subclavian artery stenosis: a review for the vascular medicine practitioner. Vasc Med. 2010;16:29–34.

Gault JH, Ross J Jr, Mason DT. Patterns of brachial arterial blood flow in conscious human subjects with and without cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 1966;34:833–48.

Guler N, Bilge M, Eryonucu B, Erkoc R, Ipeksoy U. Brachial artery blood flow velocity pattern in patients with congestive heart failure: duplex Doppler ultrasonographic assessment. Angiology. 2000;51:207–12.

Chemla D, Levenson J, Valensi P, LeCarpentier Y, Pourny JC, Pithois-Merli I, Simon A. Effect of beta adrenoceptors and thyroid hormones on velocity and acceleration of peripheral arterial flow in hyperthyroidism. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:494–500.

Bernstein DP, Lemmens HJ. Stroke volume equation for impedance cardiography. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2005;43:443–50.

Chemla D, Demolis P, Thyrault M, Annane D, Lecarpentier Y, Giudicelli JF. Blood flow acceleration in the carotid and brachial arteries: respective contributions of cardiac performance and local resistance. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1996;10:393–9.

Lindstedt SL, Schaeffer PJ. Use of allometry in predicting anatomical and physiological parameters of mammals. Lab Anim. 2002;36:1–19.

Nirmalan M, Willard TM, Edwards DJ, Little RA, Dark PM. Estimation of errors in determining intrathoracic blood volume using single transpulmonary thermodilution technique in hypovolemic shock. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:805–12.

Moller S, Henriksen JH, Bendtsen F. Central and noncentral blood volumes in cirrhosis: relationship to anthropometrics and gender. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G970–9.

Metzelder SM, Coburn M, Stoppe C, Fries M, Simon T-P, Reinges MH, Hollig A, Rossaint R, Marx G, Rex S. Accuracy and precision of calibrated arterial pulse contour analysis in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage requiring high-dose vasopressor therapy: a prospective observational clinical trial. Crit Care. 2014;18(1):R25.

Luchitskaya E, Deliere A, Diedrich N, Almorad A, Beck P, Gauger P, Limper U, Funtova I, Baevsky RM, Migeotte PF, Tank J. Timing and source of the maximum of the transthoracic impedance cardiogram (dZ/dt) in relation to the H-I-J complex of the longitudinal ballistocardiogram under gravity and microgravity conditions. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2013;2013:7294–7. doi:10.1109/EMBC.2013.6611242.

Ulbrich M, Muhlsteff J, Leonhardt S, Walter M. Influence of physiologic sources on the impedance cardiogram analyzed using 4D FEM simulations. Physiol Meas. 2014;35:1451–68.

Norozi K, Beck C, Osthaus WA, Wille I, Wessel A, Bertram H. Electrical velocimetry for measuring cardiac output in children with congenital heart disease. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:88–94.

Zoremba N, Bickenbach IJ, Krauss B, Rossaint R, Kuhlen R, Schalte G. Comparison of electrical velocimetry and thermodilution techniques for the measurement of cardiac output. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2007;51:1314–9.

Noori S, Drabu B, Soleymani S, Seri I (2012) Continuous non-invasive cardiac output measurements in the neonate by electrical velocimetry: a comparison with echocardiography. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonate Ed 97(5):F340–3. doi:10.1136/fetalneonatal-2011-301090.

Rauch R, Welisch E, Lansdell N, Burrill E, Jones J, Robinson T, Bock D, Clarson C, Filler G, Norozi K (2012) Non-invasive measurement of cardiac output in obese children and adolescents: comparison of electrical cardiometry and transthoracic Doppler echocardiography. J Clin Monit Comput 27(2):187–93. doi:10.1007/s10877-012-9412-7 [Epub 2012 Nov 21].

Grollmuss O, Gonzalez P. Non-invasive cardiac output measurement in low and very low birth weight infants: a method comparison. Front Pediatr. 2014;25(2):16. doi:10.3389/fped.2014.00016.

Grollmuss O, Demontoux S, Capderou A, Serraf A, Belli E (2012) Electrical velocimetry as a tool for measuring cardiac output in small infants after heart surgery. Intensive Care Med 38(6):1032–9. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2530-3 [Epub 2012 Mar 30].

Lorne E, Mahjoub Y, Diouf M, Sleghem J, Buchalet C, Guinot PG, Petiot S, Kessavane A, Dehedin B, Dupont H (2014) Accuracy of impedance cardiography for evaluating trend in cardiac output: a comparison with oesophageal Doppler. Br J Anaesth 28. Pii: aeu136 [Epub ahead of print].

Critchley LA, Critchley JA. A meta-analysis of studies using bias and precision statistics to compare cardiac output techniques. J Clin Monit Comput. 1999;15:85–91.

Cecconi M, Rhodes A, Poloniecki J, Della Rocca G, Grounds RM. Bench-to-bedside review: the importance of the precision of the reference technique in method comparison studies—with specific reference to the measurement of cardiac output. Crit Care. 2009;13:201. doi:10.1186/cc7129.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mathew J. Banet, Ph.D., for his efforts in organizing the study, its protocol, and acquiring the necessary initial funding. We also are indebted to Suzannah Collins for her organizational skills, especially in recruitment of volunteers and appointment scheduling. This study was supported, in part, by a grant from MRMC (U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command) of the Department of Defense, contract number W81XWH-11-2-0085 and by Sotera Wireless, Inc., San Diego, CA, 92121.

Conflict of interest

Donald P. Bernstein is a salaried employee of Sotera Wireless, Inc., San Diego, CA, and declares conflict of interest. He has equity interest, including stocks and stock options. Dr. Bernstein licensed the core patents for TBEV to Sotera Wireless, Inc., for which he received licensing fees. Isaac C. Henry reports conflict of interest, because he is a salaried employee of Sotera Wireless, Inc., and receives stock options and other financial incentives. Anthony N. DeMaria reports conflict of interest. He is currently on the Board of Sotera Wireless, Inc., and receives stock options. James B. Moon is Chief Technology Officer of Sotera Wireless, Inc. and declares conflict of interest in that he receives stock options and other financial incentives. Janell Chaltas is a paid consultant of Sotera Wireless, Inc. and otherwise declares no conflict of interest. Andrew M. Kahn and Harry J. Lemmens declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

The authors declare that this research study was conducted on human volunteers and complies with all the ethical standards of the state of California and the United States of America. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of California, San Diego, CA and Aspire Review Board, Santee, CA 92071. Informed written consent was obtained from all study subjects. This report describes an observational clinical study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bernstein, D.P., Henry, I.C., Lemmens, H.J. et al. Validation of stroke volume and cardiac output by electrical interrogation of the brachial artery in normals: assessment of strengths, limitations, and sources of error. J Clin Monit Comput 29, 789–800 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-015-9668-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-015-9668-9