Abstract

Objective

The amplitude of R-wave in DII lead (RDII) has been shown to correlate to central blood volume in animal and healthy volunteers. The aim of this study was to assess if change in RDII (ΔRDII) after passive leg rise (PLR) and fluid loading would allow detecting preload dependence in intensive care ventilated patients. This parameter was compared to concomitant changes in pulse arterial pressure (ΔPP).

Methods

Observational study in 40 stable sedated and ventilated cardiac surgery patients studied postoperatively. In line with our routine practice we performed a 45° passive leg rise (PLR1) to detect preload dependence. If cardiac index or ΔPP rose more than 12 and 13%, respectively, the patient was declared as non-responder (NR) to fluid loading. If these criteria were not met, they were declared as responders (R) and received a 500 ml of gelatin fluid loading (FL) followed by a second passive leg rise (PLR2). Hemodynamic parameters were assessed during each maneuver using their indwelling Swan-Ganz and radial catheter.

Results

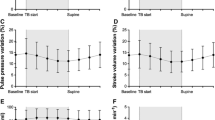

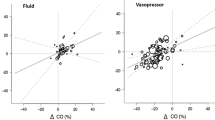

We identified 16 R and 24 NR whose hemodynamic parameters did not differ at basal condition, except ΔPP (19% ± 7 in R vs. 7% ± 4 in NR, P < 0.001). PLR1 did not elicit any hemodynamic change in NR. In R, ΔPP decreased and SV rose, both significantly (P < 0.001) whereas ΔRDII did not vary. FL induced a more pronounced change in these parameters.

Conclusions

ΔRDII in response to PLR does not successfully help identifying preload dependent patients contrarily to ΔPP or change in stroke volume.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Cardiac index,

- CVP:

-

Central venous pressure,

- DAP:

-

Diastolic arterial pressure,

- HR:

-

Heart rate,

- PAOP:

-

Pulmonary artery occluded pressure,

- PlatP:

-

Plateau airway pressure,

- PLR:

-

Passive leg rise,

- RDII:

-

Standard II ECG lead,

- SAP:

-

Systolic arterial pressure,

- SV:

-

Stroke volume,

- ΔPP:

-

Respiratory induced change in pulse pressure,

- ΔRDII:

-

Change in RDII

References

Michard F. Changes in arterial pressure during mechanical ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:419–28.

Michard F, Chemla D, Richard C, Wysocki M, Pinsky MR, Lecarpentier Y, et al. Clinical use of respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure to monitor the hemodynamic effects of PEEP. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:935–9.

Michard F, Boussat S, Chemla D, Anguel N, Mercat A, Lecarpentier Y, et al. Relation between respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure and fluid responsiveness in septic patients with acute circulatory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:134–8.

Bendjelid K, Suter PM, Romand JA. The respiratory change in preejection period: a new method to predict fluid responsiveness. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:337–42.

Brody DA. A theoretical analysis of intracavitary blood mass influence on the heart-lead relationship. Circ Res. 1956;4:731–8.

Manoach M, Gitter S, Grossman E, Varon D, Gassner S. Influence of hemorrhage on the QRS complex of the electrocardiogram. Am Heart J. 1971;82:55–61.

la Torre PK, Zaki S, Govendir M, Church DB, Malik R. Effect of acute haemorrhage on QRS amplitude of the lead II canine electrocardiogram. Aust Vet J. 1999;77:298–300.

Castini D, Vitolo E, Ornaghi M, Gentile F. Demonstration of the relationship between heart dimensions and QRS voltage amplitude. J Electrocardiol. 1996;29:169–73.

Johnson MR. Low systemic vascular resistance after cardiopulmonary bypass: are we any closer to understanding the enigma? Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1048–50.

Nashef SA, Roques F, Michel P, Gauducheau E, Lemeshow S, Salamon R. European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;16:9–13.

McManus JG, Convertino VA, Cooke WH, Ludwig DA, Holcomb JB. R-wave amplitude in lead II of an electrocardiograph correlates with central hypovolemia in human beings. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1003–10.

Hutton P, Prys-Roberts C. Monitoring in anaesthesia and intensive care. 1994.

Feldman T, Borow KM, Neumann A, Lang RM, Childers RW. Relation of electrocardiographic R-wave amplitude to changes in left ventricular chamber size and position in normal subjects. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55:1168–74.

Michard F, Teboul JL. Predicting fluid responsiveness in ICU patients: a critical analysis of the evidence. Chest. 2002;121:2000–8.

Stetz CW, Miller RG, Kelly GE, Raffin TA. Reliability of the thermodilution method in the determination of cardiac output in clinical practice. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126:1001–4.

Kramer A, Zygun D, Hawes H, Easton P, Ferland A. Pulse pressure variation predicts fluid responsiveness following coronary artery bypass surgery. Chest. 2004;126:1563–8.

Preisman S, Kogan S, Berkenstadt H, Perel A. Predicting fluid responsiveness in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: functional haemodynamic parameters including the Respiratory Systolic Variation Test and static preload indicators. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:746–55.

Morgan BC, Guntheroth WG, Mcgough GA. Effect of position on leg volume. Case against the trendelenburg position. JAMA. 1964;187:1024–6.

Rutlen DL, Wackers FJ, Zaret BL. Radionuclide assessment of peripheral intravascular capacity: a technique to measure intravascular volume changes in the capacitance circulation in man. Circulation. 1981;64:146–52.

Boulain T, Achard JM, Teboul JL, Richard C, Perrotin D, Ginies G. Changes in BP induced by passive leg raising predict response to fluid loading in critically ill patients. Chest. 2002;121:1245–52.

Monnet X, Rienzo M, Osman D, Anguel N, Richard C, Pinsky MR, et al. Passive leg raising predicts fluid responsiveness in the critically ill. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1402–7.

Albert RK, Schrijen F, Poincelot F. Oxygen consumption and transport in stable patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:678–82.

Thomas M, Shillingford J. The circulatory response to a standard postural change in ischaemic heart disease. Br Heart J. 1965;27:17–27.

Wong DH, Tremper KK, Zaccari J, Hajduczek J, Konchigeri HN, Hufstedler SM. Acute cardiovascular response to passive leg raising. Crit Care Med. 1988;16:123–5.

Wong DH, O’Connor D, Tremper KK, Zaccari J, Thompson P, Hill D. Changes in cardiac output after acute blood loss and position change in man. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:979–83.

Reich DL, Konstadt SN, Raissi S, Hubbard M, Thys DM. Trendelenburg position and passive leg raising do not significantly improve cardiopulmonary performance in the anesthetized patient with coronary artery disease. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:313–7.

Jabot J, Teboul JL, Richard C, Monnet X. Passive leg raising for predicting fluid responsiveness: importance of the postural change. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:85–90.

Fuenmayor AJ, Vasquez CJ, Fuenmayor AM, Winterdaal DM, Rodriguez D. Hemodialysis changes the QRS amplitude in the electrocardiogram. Int J Cardiol. 1993;41:141–5.

Vancheri F, Barberi O. Relationship of QRS amplitude to left ventricular dimensions after acute blood volume reduction in normal subjects. Eur Heart J. 1989;10:341–5.

Ishikawa K, Nagasawa T, Shimada H. Influence of hemodialysis on electrocardiographic wave forms. Am Heart J. 1979;97:5–11.

Ishikawa K, Shirato C, Yanagisawa A. Electrocardiographic changes due to sauna bathing. Influence of acute reduction in circulating blood volume on body surface potentials with special reference to the Brody effect. Br Heart J. 1983;50:469–75.

Vitolo E, Madoi S, Palvarini M, Sponzilli C, De MR, Ciro E, et al. Relationship between changes in R wave voltage and cardiac volumes. A vectorcardiographic study during hemodialysis. J Electrocardiol. 1987;20:138–46.

Oreto G, Luzza F, Donato A, Satullo G, Calabro MP, Consolo A, et al. Electrocardiographic changes associated with haematocrit variations. Eur Heart J. 1992;13:634–7.

Madias JE, Narayan V. Augmentation of the amplitude of electrocardiographic QRS complexes immediately after hemodialysis: a study of 26 hemodialysis sessions of a single patient, aided by measurements of resistance, reactance, and impedance. J Electrocardiol. 2003;36:263–71.

Madias JE. Comparability of the standing and supine standard electrocardiograms and standing sitting and supine stress electrocardiograms. J Electrocardiol. 2006;39:142–9.

Financial support

The authors performed this study in the course of their normal duties as full-time salaried employees of publicly funded healthcare institutions. The AFSSAPS provided the data used for the study, free of charge. The clinical department of L. Beydon provided additional funds for the data analysis.

Conflicts of interest

Christophe Soltner, MD. Romain Dantec, MD. Frédéric Lebreton, MD. Julien Huntzinger, MD. Laurent Beydon MD, PhD declare not having any conflict of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Soltner C, Dantec R, Lebreton F, Huntzinger J, Beydon L. Changes in R-Wave amplitude in DII lead is less sensitive than pulse pressure variation to detect changes in stroke volume after fluid challenge in ICU patients postoperatively to cardiac surgery.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Soltner, C., Dantec, R., Lebreton, F. et al. Changes in R-Wave amplitude in DII lead is less sensitive than pulse pressure variation to detect changes in stroke volume after fluid challenge in ICU patients postoperatively to cardiac surgery. J Clin Monit Comput 24, 133–139 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-010-9221-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-010-9221-9