Abstract

The existence of “tipping points” in human–environmental systems at multiple scales—such as abrupt negative changes in coral reef ecosystems, “runaway” climate change, and interacting nonlinear “planetary boundaries”—is often viewed as a substantial challenge for governance due to their inherent uncertainty, potential for rapid and large system change, and possible cascading effects on human well-being. Despite an increased scholarly and policy interest in the dynamics of these perceived “tipping points,” institutional and governance scholars have yet to make progress on how to analyze in which ways state and non-state actors attempt to anticipate, respond, and prevent the transgression of “tipping points” at large scales. In this article, we use three cases of global network responses to what we denote as global change-induced “tipping points”—ocean acidification, fisheries collapse, and infectious disease outbreaks. Based on the commonalities in several research streams, we develop four working propositions: information processing and early warning, multilevel and multinetwork responses, diversity in response capacity, and the balance between efficiency and legitimacy. We conclude by proposing a simple framework for the analysis of the interplay between perceived global change-induced “tipping points,” global networks, and international institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Global environmental change can unfold rapidly and sometimes irreversibly if anthropogenic pressures exceed critical thresholds. Such nonlinear change dynamics have been referred to as “tipping points”.Footnote 1 Evidence indicates that many global environmental challenges such as coral reef degradation, ocean acidification, the productivity of agro-ecosystems, and critical Earth system functions such as global climate regulation display nonlinear properties that could imply rapid and practically irreversible shifts in bio-geophysical and social–ecological systems critical for human well-being (Steffen et al. 2011; Rockström et al. 2009; Lenton et al. 2008).

The potential existence of “tipping points” represents a substantial multilevel governance challenge for several reasons. First, it is difficult to a priori predict how much disturbances and change a system can absorb before reaching such a perceived “tipping points” (Scheffer et al. 2009; Scheffer and Carpenter 2003), a fact that seriously hampers, and even undermines preventive decision making (Galaz et al. 2010a; Barrett and Dannenberg 2012). It has also been argued that even with certainty about the location of a catastrophic “tipping point,” present generations still have an incentive to avoid costly preventive measures, and instead are likely to pass on the costs to future generations (Gardiner 2009, see also Brook et al. 2013; Schlesinger 2009). Second, the transgression of “tipping points”—such as those proposed for coral reef ecosystems due to ocean acidification—can have social–ecological effects that occur over large geographical scales, creating difficult “institutional mismatches” as policy makers respond too late or at the wrong organizational level (Walker et al. 2009). Third, institutional fragmentation has been argued to seriously limit the ability of actors to effectively address perceived “tipping point” characteristics due to inherent system uncertainties, information integration difficulties, and poor incentives for collective action across different sectors and segments of society (Biermann 2012; Galaz et al. 2012).

Research initiatives such as the Earth System Governance Project have made important analytical advances the last few years (Biermann et al. 2012). This progress is particularly clear in research areas such as institutional fragmentation, segmentation, and interactions; the changing influence of non-state actors in international environmental governance; novel institutional mechanisms such as norm-setting and implementation; and changing power dynamics in complex actor settings (Young 2008; Biermann and Pattberg 2012; Oberthür and Stokke 2011). The mechanisms which allow institutions and state and non-state actors to adapt to changing circumstances (by some denoted adaptiveness) are also gaining increased interest by scholars (Biermann 2007:333; Young 2010).

Another stream of literature elaborates a suite of multilevel mechanisms that seem to be able to “match” institutions with the dynamic behavior of social–ecological systems (Dietz et al. 2003; Folke et al. 2005; Cash et al. 2006; Galaz et al. 2008; Pahl-Wostl 2009).

Despite an increased interest, however, few empirical studies exist that explicitly explores the capacity of international actors, institutions, and global networks to deal with perceived “tipping point” dynamics in human–environmental systems. As an example, recent syntheses of critical global environmental governance challenges in the Anthropocene identify important “building blocks” for institutional reform, yet do not elaborate governance mechanisms critical for responding to nonlinear environmental change at global scales (Biermann et al. 2012; Kanie et al. 2012). This is troublesome considering that the human enterprise now affects systems with proposed nonlinear properties at the global scale (Steffen et al. 2011; Rockström et al. 2009) and that the features of global environmental governance—i.e., institutions and patterns of collaboration—required to address “tipping point” changes are likely to be very different from those needed to harness incremental (linear) environmental stresses (Folke et al. 2005; Duit and Galaz 2008). While some of the challenges explored here have parallels to attempts to understand the features of international responses to international social nonlinear “surprise” phenomena such as financial shocks and other global risks (e.g., Claessens et al. 2010; OECD 2011), we are particularly interested in the “tipping point” dynamics created by coupled human–environmental change.

2 A contribution

There is an increasing need to empirically explore and theorize the way state and non-state actors perceive, respond to and try to prevent large-scale abrupt environmental changes. This is a challenging empirical task for several reasons. First, because the definitions of “thresholds,” their reversibility, and their scale remain contested issues. There is currently an intense scientific debate on the most appropriate way to define and delineate the correct spatial (local–regional–global) and temporal (slow–fast) progression of thresholds (for example, see Brook et al. 2013, as well as debates about the “2-degree” climate target, Hulme 2012 in Knopf et al. 2012). Second, because the number and types of potential “tipping points” relevant for the study of biophysical systems at global scales are too large to be quantifiable, this makes it difficult to draw general conclusions from a limited set of cases studies. Third, while the governance challenges associated with “tipping points” have been studied extensively for local- and regional-scale human–environmental systems such as forest ecosystems, freshwater lakes, wetlands, and marine systems (see Plummer et al. 2012 for a synthesis), governance challenges associated with global scale or global change-induced tipping point dynamics are seldom explored despite their identified urgency (Young 2011: 6).

In this study, we analyze current attempts by three global networks to address perceived “tipping points” induced by global change, here exemplified by the combined impacts of loss of marine biodiversity and ocean acidification, pending fisheries collapse, and infectious disease outbreaks, respectively. While these “tipping points” are in many ways different, they have one important thing in common: they are all globally occurring phenomena where the interplay between technological change, increased human and infrastructural interconnectedness, and continuous biophysical resource overexploitation creates possible “tipping point” dynamics (see definition below). This is what we here denote as “global change-induced tipping points.”

It should be noted that the precise dynamics of the “tipping points” in each of the three cases differ and unfold at multiple scales ranging from local to regional and global (see Table 1 for details). Despite this diversity, the phenomena studied here all pose similar detection, prevention, and coordination challenges for social actors at multiple scales of social organization (as elaborated by, e.g., Adger et al. 2009; Pahl-Wostl 2009; Galaz et al. 2010a; Young 2011). Hence, they provide interesting and preliminary insights into the sort of multilevel governance challenges associated with nonlinear global change-induced change.

Our ambition is twofold: firstly, we investigate how these global networks attempt to identify, respond to, and build capacity to address global change-induced “tipping points.” We do this by identifying and empirically illustrating four working propositions that theoretically seem to be essential for understanding adaptiveness in global networks in the face of “tipping point” changes. Secondly, we explore the interplay between perceptions of human–environmental “tipping points,” international institutions, and collaboration patterns here operationalized as global networks. This perspective allows for a more cohesive view that combines both exogenous (i.e., perceived “tipping point” dynamics) and endogenous (i.e., information sharing mechanisms) factors (sensu Young 2010). We will return to this point in the end of the article. Note that, our ambition is not to “test” the proposed features in a statistical sense, but rather to combine in-depth analysis of the case studies, with tentative suggestions that bring to light a number of intriguing and poorly explored issues. While the selection of cases does not provide the generalizability of larger-N studies, it does allow us to examine how the theoretically derived propositions play out in the three different cases, and also provides an opportunity to explore around the potential interplay between variables and causal mechanisms. Our ambition in the longer term is that the analysis presented here can underpin more systematic cross-case comparisons (cf. Gerring 2004). In some cases, this comparison could be done with “tipping points” which play out only in the social domain such as financial crises or responses to transnational security threats (e.g., World Economic Forum 2013).

3 Definitions

3.1 Global networks

We define “global networks” as globally spanning information sharing and collaboration patterns between organizations, including governmental and/or non-governmental actors. Each individual participating organization is not necessarily global, but the network as a whole is essentially international and aims to affect what is perceived as global-scale problems (c.f. Monge and Contractor 2003).

Our analytical approach is relational as it focuses on broad patterns of collaborations among actors in global networks, and on how patterns of collaboration and modes of operation relate to these networks’ abilities to address “tipping points.” It is particularly concerned with multiactor agency to understand changes in collaboration over time (Emirbayer and Goodwin 1994). Hence, the approach here differs and is complementary to other approaches such as “epistemic communities” and “regime complexes.” In the first case, the functions and membership of global networks are more diverse than those for epistemic communities as the networks of interest in this paper span beyond knowledge-based collaborations (Haas 1992, see however Cross 2012 for a wider definition). The analysis here also has some similarities to the studies of “regime complexes” (Orsini et al. 2013); however, our emphasis is not on the interplay between regimes or institutions (principles, norms, rules, decision-making procedures), but rather on the constellation, interplay, and functions that emerge between actors from a network perspective.

While we do not quantitatively measure collaboration patterns, nor quantitatively assess governance outcomes or relationships between such outcomes and various characteristics of the studied global networks, our network perspective complements previous analyses of international environmental regimes (e.g., Young 2011) as it examines the evolution and function of globally spanning network collaboration patterns and their embeddedness within more formal rules (cf. Ansell 2006).

3.2 “Tipping points” and thresholds

Various definitions for “tipping points” have been identified in the literature. Its theoretical origins can be traced to dynamical systems theory in the 1960s and 1970s, and has influenced a wide set of disciplines the last decades. Earth system scientists, for example, have explored nonlinear phenomena at different scales, with different degrees of reversibility and alternately defined these as “tipping elements,” “switch and choke points,” or “planetary boundaries” at a global scale (Lenton et al. 2008; Rockström et al. 2009b; Steffen et al. 2011).

Ecologists on the other hand find increasing evidence of ecosystem changes that are not smooth and gradual, but abrupt, exhibiting thresholds with different degrees of reversibility once crossed (Scheffer et al. 2009; Scheffer and Carpenter 2003). While “tipping points” thus refer to a variety of complex nonlinear phenomena (including the existence of positive feedbacks, bifurcations, and phase transitions with or without hysteresis effect), they also play out at different scales (from local to global) in very complex, poorly understood (Kinzig et al. 2006), and contested ways (Brook et al. 2013).

Lastly, we believe there is an irreducible social component in identifying, elaborating, and organizing around the existence of “tipping points.” The role of mental models, cognitive maps, belief systems, and collective meaning making in decision making has a long history in the study of agency in politics (Benford and Snow 2000; Campbell 2002) and natural resource management (Lynam and Brown 2011). These aspects related to perceptions clearly also play a role as scientists, governments, and other actors discuss and sometime disagree on their possible existence and appropriate responses (Galaz 2014:16ff). The important connection between mental models and goal-oriented action are causal beliefs—perceptions of the causes of change—and about the actions that can lead to a desired outcome (Milkoreit 2013:34f). It should be noted, however, that this study explores the processes of collaboration that occur after social actors implicitly have agreed upon causal beliefs associated with perceived “tipping points.”

We thus recognize the multifaceted and complex nature of the term. However, as our goal is to understand how global networks address a diversity of “tipping points” induced by global change, we opt for a definition that relates to phenomena exhibiting nonlinear and potentially irreversible change processes in human–environmental systems, which require global responses (see Table 1). This definition is intended to capture global change-induced phenomena, which due to nonlinear properties such as synergistic feedbacks (c.f. Brook et al. 2013:2) have the potential to affect large parts of the world population (c.f. Lenton et al. 2008).

Our definition is akin to the “tipping elements” identified by Lenton et al. (2008), but we chose to make a distinction for two reasons: (1) because we explicitly acknowledge that the dynamics that create the tipping points in focus comprise both natural and social processes; (2) the tipping points addressed here span beyond those of relevance for the climatic system in focus in Lenton et al. (ibid).

4 Case studies and methods

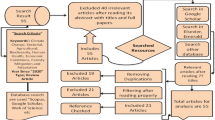

The empirical analysis includes case studies of three global networks (Fig. 1) that with varying degrees of outputs and outcomes (sensu Young 2011) explicitly attempt to respond to global change-induced “tipping points” (Table 1). By “explicitly,” we mean that they all acknowledge and mobilize their actions around the notion of potentially harmful global change-induced “tipping points.” While this selection does not capture cases where “tipping points” exist, but global networks fail to materialize (c.f. Dimitrov et al. 2007), the ambition has been to include cases that reflect a diversity of global change-induced “tipping point” dynamics, with global network responses as common features.

As noted by Mitchell (2002), the complexity of human–environmental systems makes outcomes of international environmental collaboration hard to measure directly, since these often have indirect and non-immediate impacts (Mitchell 2002:445). To operationalize the analysis, we thus focus on the outputs and outcomes produced by the actors as they attempt to (a) anticipate, (b) prevent, and (c) respond to perceived “tipping points.” Again, our ambition is not to “test” the propositions, but rather to use the case studies to empirically explore how global networks attempt to respond to “tipping point” challenges, pose novel important questions, and explore how to potentially pursue these questions systematically.

4.1 Case 1. Pacfa: global partnership climate, fisheries, and aquaculture

Ocean acidification is likely to exhibit critical tipping points associated with rapid loss of coral reefs, as well as complex ocean–climate interactions affecting the oceans’ capacities to capture carbon dioxide. The global arena for addressing these interrelated aspects of marine governance is characterized by a lack of effective coordination among the policy areas of marine biodiversity, fisheries, climate change, and ocean acidification. This has triggered collaboration between a number of international organizations within the Global Partnership for Climate, Fisheries and Aquaculture (henceforth Pacfa). Currently, this initiative includes representatives from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), WorldFish, The World Bank, and 13 additional international organizations (Galaz et al. 2011, see also Fig. 1).

4.2 Case 2. Global epidemic early warning and response networks

The need for early and reliable warning of pending epidemic outbreaks has been a major concern for the international community since the mid-nineteenth century. Early warning and coordinated responses are critical in order to avoid transgressing critical epidemic thresholds at multiple scales (Heymann 2006). A multitude of networks with different focus and functions (such as surveillance, laboratory analysis, and pure information sharing) have emerged the last two decades as a means to secure early warning and response capacities across national borders. These networks (henceforth global epidemic networks) also span across organizational levels and include among other the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), the Red Cross, Doctors without Borders. These networks facilitate responses to epidemic emergencies of international concern by providing early warning signals, rapid laboratory analysis, information dissemination, and coordination of epidemic emergency response activities on the ground (Galaz 2011) .

4.3 Case 3. A global network to address illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing in the Southern Ocean

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing for Patagonian toothfish Dissostichus eleginoides can if unchecked, lead to the collapse of valuable fish stocks and endangered seabird populations (Table 1). The toothfish market and actors involved in IUU fishing are distributed globally, which necessitates coordination between states on all continents. State and non-state actors have increasingly developed their networks for cooperation and are currently operating at the global level (Fig. 1) through the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (henceforth CCAMLR) and associated actors (Österblom and Bodin 2012). Coordinated international responses on important fishing grounds have resulted in a dramatic reduction in IUU fishing. States now have well-developed mechanisms for coordinated monitoring and response when new actors, markets, or IUU fishing emerge in the Southern Ocean (Österblom and Sumaila 2011).

4.3.1 Methods

The data used in this article are drawn from previously published studies (see “Appendix 2”), but complemented with additional documents, and restructured with a focus on the four working propositions presented below. All cases used the same methodology, combining document studies, simple network analysis, and semi-structured interviews with key international actors (a total of about 65 interviews for all cases). Interviewees have been selected strategically to reflect an expected diversity of interests, resources, and role in the network collaboration of interest. The empirical material was restructured and complemented to capture (1) the perceived risk of “tipping points” with cross-boundary effects, including major uncertainties, threshold mechanisms, and time frames of relevance; (2) the global nature of the problem, including the aspects of institutional fragmentation; (3) emergence of the network and evolution over time; (4) current monitoring and coordination capacity of the network; (5) the most important outputs and outcomes of the network. A detailed, fully referenced and structured compilation of the cases is for space reasons, available as “Appendix 2.”

5 Four working propositions

Several attempts have been made to identify how governments, organizations, and international actors attempt to not only maintain institutional stability, but also flexibility in the face of unexpected change (Duit and Galaz 2008). Studies of crisis management (Boin et al. 2005), network management and “connective capacity” in governance (Edelenbos et al. 2013), the robustness of social and organizational networks (Dodds et al. 2003; Bodin and Prell 2011), complexity leadership (Balkundi and Kilduff 2006), and the governance of complex social–ecological systems (Ostrom 2005; Folke et al. 2005; Pahl-Wostl 2009) all provide important insights into how social actors try to respond to unexpected changes. Based on these streams of literature, we extract four working propositions to guide the analysis of the empirical material. These propositions should not be viewed as all-embracing principles for “success,” but rather as suggested and empirically assessable governance functions at play as international actors aim to detect, respond, and prevent the implications of “tipping point” environmental change. The propositions also allow a concluding reflection of the interplay between international institutions, global change-induced “tipping points,” and global networks.

5.1 Proposition 1: information processing and early warnings

As a number of research fields—ranging from studies of social–ecological systems (Holling 1978; Folke et al. 2005; Galaz et al. 2010b), crisis management (Boin et al. 2005), global disaster risk reduction (Van Baalen and van Fenema 2009), and high-reliability management of complex technical systems (Pearson and Clair 1998)—have explored, the capacity to continuously monitor, analyze, and interpret information about changing circumstances seems to be a prerequisite for adaptive responses. These information processing capacities are for example identified as critical by, e.g., Dietz et al. (2003:1908) in their elaboration of the features of governance, which support adaptiveness to environmental change; Van Baalen’s and van Fenema’s (2009) analysis of global network responses to epidemic surprise; and by Boin et al. (2005:140ff) and their synthesis of information processing capacities, which allow state and non-state actors to respond to crises (see also Comfort 1988; Dodds et al. 2003).

We therefore propose that the ability of global networks to anticipate and reorganize in the face of new information and changing circumstances will depend on access to information about system dynamics and the ability to interpret these to facilitate timely coordinated response.

5.2 Proposition 2: multilevel and multinetwork responses

As a number of studies in a diverse set of research fields suggest, responding to changing circumstances often requires drawing on the competences and resources of actors at multiple levels of social organization, often embedded in different organizational networks. For example, Folke et al. (2005) explore the need to build linkages between a diversity of actors at multiple levels to be able to successfully deal with nonlinear social–ecological change (see also Pahl-Wostl 2009); Pearson and Clair’s (1998:13) synthesis of organizational crises identify resource availability through external stakeholders as key for successful responses (see also Boin et al. 2005; Van Baalen and van Fenema 2009); Galaz et al. (2010a:12) synthesis also indicate that cross-level and multiactor responses are key for overcoming institutional fragmentation in responses to abrupt human–environmental change; and Edelenbos et al. (2013) explore the features of “connective capacities,” which allow coordinating actors to constructively connect to actors from different layers, domains, and sectors.

Therefore, we propose that global networks need to build a capacity to coordinate actors at multiple levels and from different networks as they attempt to respond to potential “tipping points” of concern. It also seems reasonable that responses could focus on producing either a set of outcomes (regulation, polices, or supporting infrastructure) or outputs (behavioral changes with direct impacts on the system of interest, including coordinated action) (Young 2011).

5.3 Proposition 3: develop and maintain a diverse response capacity

The predictability of the timing and location of rapid unexpected changes is often limited. Hence, it is difficult to know beforehand exactly where and what kind of resources may be needed. As several scholars across disciplines have noted, developing and maintaining a diversity of resources is one way to help prepare for the unexpected. For example, Moynihan’s (2008:361) analysis of learning in organizational networks indicates that the maintenance of actor and resource diversity in networks is fundamental for reducing strategic and institutional uncertainty (see also Koppenjan and Klijn 2004). Bodin and Crona (2009) explore the role of social networks in natural resource management and note that actor diversity is key for not only effective learning, but also provides a fertile ground for innovation. Social–ecological scholars such as Folke et al. (2005:449), Low et al. (2003), and Dietz et al. (2003) also make a strong case for institutional and actor diversity as a prerequisite for coping with environmental change and as a factor that allows actors to quickly “bounce back” after shocks. These proposals bear resemblances with ideas inspired by cybernetic principles about the need to understand the impacts of “requisite variety” in governance, that is, the informational, structural, and functional redundancies that emerge as the result of inter-organizational collaboration in governance networks (Jessop 1998). It also has parallels existing studies about complexity leadership in network settings (Balkundi and Kilduff 2006; Hoppe and Reinelt 2010). To simplify the analysis, however, we focus less on the role of individual leaders, their cognition, and strategies, but rather on common structural properties and aggregated behavior across the cases.

Hence, we propose that global networks need to secure long-term access to a diversity of resources (human and economical), organizational forms (e.g., non-governmental to international organizations), and types of knowledge (e.g., scientific and context dependent) to be able to secure a capacity to monitor and respond in the longer term. These resources could comprise both physical and infrastructural investments (e.g., joint publications and monitoring systems), and immaterial resources, like information databases and access to expertise through relations to a diversity of actors. This third proposition does not suggests that the network necessarily maintains the resources itself (which may be difficult given its inherently distributed nature), but rather that it maintains the capacity to access a portfolio of resources of different kinds, and the collective ability to adaptively use these.

5.4 Proposition 4: balancing legitimacy and efficiency goals

A last feature that has been identified across disciplines as critical for multiactor responses seems to be legitimacy. “Legitimacy” is a multifaceted concept with multiple proposed sources (Downs 2000). Here, we refer to legitimacy as the “generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate” (Suchman 1995, 574). As Young (2011) summarizes it, the “[m]aintenance of feelings of fairness and legitimacy is important to effectiveness, especially in cases where success requires active participation on the part of the members of the group over time.” Legitimacy relates not only to the ability of actors to follow appropriate rules or procedures (input legitimacy) but also to deliver expected results in the face of perceived urgent issues of common interest (output legitimacy) (van Kersbergen and van Waarden 2004). Moynihan (2008) also notes that trust based on perceived legitimacy plays a key role in the coordination of multiple networks by reducing strategic uncertainty (pp. 357). We therefore propose that the perceived legitimacy of the main coordinating actor(s) will be critical for the operation of global networks in this context.

With these propositions to guide our analysis, we now turn to examine how the three cases of global networks attempt to anticipate, prevent, and respond to global change-induced “tipping points.”

6 Summary of results

Note again that this part builds exclusively on a lengthier synthesis of the case studies presented in “Appendix 2.”

6.1 Information processing and early warnings

Interestingly, all cases feature the role of a few centrally placed actors responsible for continuous data gathering and exchange of information. This is both related to monitoring of specific aspects of a system (e.g., number and location of epidemic outbreaks, or reports of IUU fishing), as well as to the compilation and analysis of other types of knowledge exchange (e.g., policy documents, technical guidelines, and scientific information).

The mobility of IUU fishing vessels and associated products requires network members to be able to instantly coordinate action in order to stop illegal activities. The CCAMLR-IUU network has developed mechanisms for obtaining, processing, and sharing of information related to IUU fishing operations and trade flows, where the CCAMLR secretariat serves as an important network hub (Österblom and Bodin 2012). This network benefits from several well-established compliance mechanisms developed over time, including an electronic catch documentation scheme and information collected from satellite monitoring of vessel activities (Miller et al. 2010). Non-state actors also contribute to monitoring by reporting suspected vessel sightings or trade flows (Österblom and Bodin 2012). All information collected is reviewed annually by CCAMLR, where consensus decisions are taken to blacklist suspected vessels or impose other sanctions.

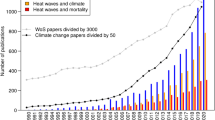

Similar features can be identified for information processing in global epidemic networks. Severe problems with national reporting of disease outbreaks spurred a new generation of Internet-based monitoring systems in the mid-1990s, including the Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN) hosted by Health Canada, combining Internet data-mining technologies and expert analysis, as well as global and moderated epidemic alert e-mail lists and platforms such as ProMED and HealthMap.org (Galaz 2011). These systems have vastly increased the amount of epidemic early warnings processed by key international organizations such as the WHO and the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). These organizations are key actors through their capacities to continuously assess, verify, and disseminate incoming epidemic alerts.

The rich flows of information and elaborate verification mechanisms in these two networks are very different from those identified for Pacfa. Information flows in this network are considerably less formalized and instead center on establishing dialogue between centrally placed individuals who act as points of contact in different international and regional organizations. The importance of trust-based communication between coordinating actors is important for Pacfa as alliances are forged to link international negotiations, scientific knowledge and local knowledge, and field projects (Galaz et al. 2011). Here, therefore, information processing is not about monitoring a particular system variable (i.e., number of infected cases or reports of illegal fishing vessels), but rather on achieving coordination benefits for its members.

Hence, while information processing is important in all cases, it differs in content and function between the networks. The fact that the first two networks respond to well-defined problems (inception of illegal vessels in one region and the isolation of disease outbreak) and the last to more complex global challenges (i.e., global interlinked bio-geophysical dynamics) seems to make an important difference.

6.2 Multilevel and multinetwork responses

While multilevel governance is a common feature of environmental polity in general (Winter 2006), governing “tipping points” requires a capacity among centrally placed actors, to rapidly pool resources from participating network members at multiple levels. Figure 2 is based on two case analyses (see “Appendix 2” for details) and illustrates these multilevel collaboration and information sharing processes.

Multilevel and multinetwork responses. a Examples of detection, coordination, and apprehension of vessels or corporations suspected of IUU fishing. The vessel “Viarsa” was detected in the Southern Ocean by the Australian coast guard and suspected of illegally fishing of Patagonian toothfish. After the longest maritime hot pursuit in maritime history (7,200 km) and substantial diplomatic coordination, the vessel was seized after the combined effort from Australian, South African, and UK assets. The charges were eventually dropped. b Examples of detection and response to emerging infectious diseases of international concern. The first signs of a new flu A/H1N1 (“swine flu”) could be found early in local news reports posted on HealthMap. It was one report by the early warning system GPHIN that alerted the WHO of an outbreak of acute respiratory illness in the Mexican state of Veracruz. This induced several iterations of communication between Mexico and the WHO (2), as well as sharing of virus samples to US and Canadian medical laboratories (3). At this stage, the WHO also issued several recommendations to its member states (4). This initiated a chain of national responses (some clearly beyond WHO recommendations), including thermal screening at airports, travel restrictions, and trade embargoes (5). The suspected causative agent of A/H1N1 induced stronger collaboration between WHO, FAO, and OIE, and the expansion of associated expert groups to include swine flu expertise resulting in continuous recommendations to member states (6). DAFF (AU) Department of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Forestry (Australia), FCO (UK) British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, United Kingdom, ASOC Antarctic Southern Ocean Coalition, AFMA (AU) Australian Fisheries Management Authority, MCM (ZA) Marine and Coastal Management (Department of Environmental Affairs, and Tourism), South Africa, WHO The World Health Organization, FAO The Food and Agricultural Organization, PAHO The Pan American Health Organization, OIE The World Organization for Animal Health, GPHIN The Global Public Health Intelligence Network, ProMED Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases

National delegations to CCAMLR integrate several types of actors, including NGOs and fishing industry representatives, who in turn are also members in ASOC, the Antarctic Southern Ocean Coalition (a global NGO network) or COLTO—Coalition of Legal Toothfish Operators (an industry network). This network can coordinate actors within matters of days and involve rapidly mobilizing capacity to apprehend illegal vessels (Fig. 2a).

Global epidemic networks are also nested in a larger global network landscape, with a similar ability to rapidly react to epidemic early warnings, including the identification of the SARS coronavirus, analysis and response to an unknown form of influenza in Madagascar, and prevention of epidemics of yellow fever in Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal. Which national, regional, or international organization that becomes the central coordinator depends on the disease agent and location of interest. However, the WHO Global Outbreak and Response Network (GOARN) and the FAO Emergency Centre that facilitates coordination for Transboundary Animal Diseases (ECTAD) (Fig. 2b) are well-known key coordinating players.

While the Pacfa network does not respond to rapidly unfolding system dynamics per se, it tries to identify political opportunities in international policy arenas as a way to prevent “tipping points” related to marine systems and biodiversity. Hence, the coordination challenges across multiple levels are similar as those identified for the other two networks, but with a different focus. For example, while a overall network aim was initially to influence international climate negotiations in Copenhagen 2009 to integrate marine issues, the path toward this goal consisted of multiple coordinated actions at multiple levels (from assessing potential adaptation needs locally, communicating these, and influencing national delegations at side events to COP15). This required a capacity among a core group of actors (FAO) to tap into resources and knowledge across levels and networks, including international scientific institutions (such as ICES), international organizations (World Bank), and place-based research NGOs (WorldFish) (Galaz et al. 2011).

6.3 Development and maintenance of diverse response capacity

Maintaining response capacity over time requires maintaining access to diverse resources and competences. All three cases examined here have evolved through time by strategically expanding the membership of the network to increase their “portfolio diversity.” CCAMLR hosts and funds strategic training workshops in regions where effective response capacities have been viewed as lacking (e.g., in Southern Africa and Malaysia). Several member countries cooperate extensively around offshore monitoring and training, in order to improve the joint enforcement capacity of the network (Österblom and Bodin 2012). Actors within the network—coordinated nationally, between organizations or between groups of countries—also continuously develop suggestions for new and revised policy measures to address IUU fishing.

Global epidemic networks have stretched over time as the result of an explicit strategy to expand international surveillance and response networks, particularly in epidemic hot-spot regions where surveillance is weak (e.g., Asia and Africa) and for diseases perceived as critical for the international community (such as avian influenza). The expansion is both strategic and crisis-driven, and involves continuous capacity building through workshops, conferences, and guidelines (e.g., Heymann 2006).

Similarly, Pacfa has expanded membership in parts of the world where representation is missing and where tangible field presence could prove useful for attempts to link local governance to global institutional processes. It has also included member organizations of various types—from NGOs to scientific organizations—as an explicit strategy to increase skills and resource portfolios. This has also proven as a fruitful way to create a platform for exchange of knowledge, ideas, and information among members. This seems to improve the network’s capacity to coordinate local responses (such as improved local marine governance in the face of ocean acidification) and integrate scientific advice into negotiation texts for international policy improvement (Galaz et al. 2011).

6.4 Balancing legitimacy and efficiency goals

The synthesis indicates that issues of legitimacy are constantly being debated in all networks, but that their responses differ. In general, however, centrally placed actors seem to build legitimacy by strategically enhancing the diversity and number of members, increasing the degree of formalization in what originally were informal collaboration mechanisms, and by encouraging the entrenchment of the networks in various UN organizations.

Cooperation within CCAMLR to address IUU fishing emerged in a context where there was a significant risk of fish stock collapse, but where governments were unable to effectively act due to political sensitivities and constraints posed by consensus mechanisms in the network (Österblom and Bodin 2012). Controversial and unorthodox methods for conveying the importance of addressing IUU fishing were instead developed by a small NGO–fishing industry coalition in the mid-1990s (Österblom and Sumaila 2011). A few governments in parallel also began exerting diplomatic pressure on member states of the Commission that were associated with illegal fishing, for example as flag, or port states or with their nationals working on board IUU vessels or as owners of associated companies.

This has at times resulted in substantial controversy and heated debate between member states about responsibilities and the role of NGOs in CCAMLR. Joint enforcement operations in the Southern Ocean have been described as pushing the edge of international law (Gullett and Schofield 2007), and suspected offenders have stated that they do not recognize existing territorial claims in the CCAMLR area as legitimate (Baird 2004). Continuous improvements of conservation measures and decision-making processes in CCAMLR have proven important for securing legitimacy of procedures. Legitimacy issues are also addressed by making Commission reports available online (except for background reports and reports containing diplomatically sensitive material).

The Pacfa has also struggled to balance legitimacy and efficiency. As the goal to influence the UNFCCC process emerged, the ambitions of Pacfa also become more explicitly political. This created tensions in the network between actors wanting to achieve tangible outcomes (and thus output legitimacy), and those concerned with overstepping their respective organizations’ mandate (thus maintaining input legitimacy). A clear fault line with respect to this was observed between central international organizations and those representing science-based organizations in the buildup to the climate negotiations in Copenhagen 2009. While most of the activities initially evolved through the work of a few centrally placed actors with modest formal support from the FAO and its member states (Galaz et al. 2011), the network has become increasingly formalized and recently became a UN Oceans-Taskforce, which is likely to increase the network’s input legitimacy in the UN system.

Addressing the risks of novel infectious disease outbreaks has been very high on the political agenda for the last decade, especially in the face of recurrent outbreaks of novel animal influenzas with the capacity to infect humans. Information processing and coordination work is currently supported through the revised International Health Regulation (IHR). However, this cooperation model orchestrated by the WHO has also raised severe issues of both input and output legitimacy, especially issues such as the role of scientific advice and the influence of pharmaceutical companies; vaccination recommendations associated with the last pandemic outbreak (“swineflu” A/H1N1); and unequal global access to treatments. This has led to repeated calls for governance reforms aiming to increase transparency, effectiveness, and benefit sharing.

It should be noted that border protection issues, primarily associated with the fear of new terror attacks after September 11 2001 in the form of intentional releases of novel diseases, have triggered substantial investments in global epidemic monitoring and response networks for disease outbreaks. Analogous national security concerns in Australia after the national elections in the year of 2001, and the Bali bombings in 2002, likely contributed to an increased political opportunity to invest substantially in monitoring technologies for the Southern Ocean, as border protection became “securitized” (Österblom et al. 2011). In addition, international cooperation and exchange of information between compliance officers has increased substantially after the terrorist attacks in New York City in 2001. The expansion of the studied two networks described here thus appears to be linked to the securitization of the issue areas, which may have important implications for their perceived legitimacy in the future (c.f. Curley and Herington 2011).

7 Networks, tipping points, and institutions: concluding reflections

Here, we examined three globally spanning networks that all attempt to respond to a diverse set of perceived global change-induced “tipping points.” As the analysis shows, the working propositions have highlighted several interesting functions worth further critical elaboration, associated with the attempts to govern complex, contested, and “tipping point” dynamics of global concern (summarized in Table 2).

In short, we have illustrated how state and non-state actors (here operationalized as global networks) attempt to build early warning capacities and improve their information processing capabilities; how they strategically expand the networks, as well as diversify their membership; how they reconfigure in ways that secures a prompt response in the face of abrupt change (e.g., novel rapidly diffusing disease, illegal fishery) or opportunities (e.g., climate negotiations); and how they mobilize economical and intellectual resources fundamentally supported by advances in information and communication technologies (e.g., through satellite monitoring and Internet data mining).

But crises responses are only one aspect of these networks. Between times of abrupt change, centrally placed actors in the networks examined are involved in strategic planning aiming to bridge perceived monitoring or response gaps, capacity building needs, and secure longer-term investments. Maintaining legitimacy seems to be critical also empirically for the ability of global networks to operate over time.

Preventing the transgression of perceived critical “tipping points,” however, requires not only early warning and response capacities, but also an ability to address complex and underlying human–environmental drivers that contribute to the problem at hand (Walker et al. 2009). It is important to note that none of the networks studied here have neither the ability nor the mandate to directly address key underlying drivers such as climate change (e.g., for ocean acidification), land-use changes (e.g., associated with changed zoonotic risks), or technological change (e.g., contributing to increased interconnectedness and the loss of marine biodiversity). Hence, it remains an open question whether global networks as the ones studied here will ever be able to collaborate if stipulated goals become more conflictive and complex, due to interactions between global drivers such as technological, demographical, and environmental (Galaz 2014).

7.1 Are global networks mere “symptom treatment”?

Yet, it would be a mistake to discard global networks as mere “symptom treatment.” The issues elaborated here not only exemplify how interacting institutions affect human–environmental systems at global scales (Gehring and Oberthür 2009). The cases also display how global networks attempt to complement functional gaps in the complex institutional and actor settings in which they are embedded. The perceived “sense of urgency” (i.e., avoiding the next pandemic, coping with potentially rapid ecological shifts in marine systems, or avoiding large-scale fish stock collapses) seemingly triggers the emergence of global networks created by concerned state and non-state actors. Figure 3 illustrates this proposed interplay between international institutions, perceptions of “tipping points,” and global networks.

By shaping state and non-state action, international institutions play a critical role in affecting the creation of potential global change “tipping points” (a in Fig. 3) (Young 2008, 2011). These perceived “tipping points” also create mixed incentives (b) for collective action. While coordination failure is likely due to actor, institutional, and biophysicial complexity (Young 2008), the perceived urgency of the issue can also create incentives for action among international state and non-state actors, and spur the emergence of global networks based on common causal beliefs (b). These networks can support the enforcement (c) of existing international institutions through their ability to process information and coordinate multinetwork collaboration, as well as create the endogenous and exogenous pressure needed to induce changes in international institutions. As Young notes, these sort of self-generating mechanisms can help build adaptability (d) and combat “institutional arthritis” (Young 2010, 382).

For example, the emergence of novel zoonotic diseases (such as avian influenza) is intrinsically linked to the effectiveness of a suite of institutional rules at multiple levels, e.g., though urbanization, land-use change, and technological development (interplay). The potential of these diseases to rapidly transgress dangerous epidemic thresholds creates incentives for joint action, in this case through the emergence of global early warning and response networks, despite malfunctioning formal institutions (e.g., IHRs before the year 2005). As nation states agreed to reform the IHRs in 2005, the revisions built on technical standards, organizational operation procedures, and norms developed by WHO-coordinated networks years in advance (adaptability) (Heymann 2006).

A similar mechanism seems to be at play for illegal, IUU fisheries. As the regional mandate of the existing international governance institution for IUU fishing proved insufficient (interplay), and the perceived threat of potential detrimental “tipping points” was perceived as valid (incentives), state and non-state actors increasingly developed their networks to operate at the global level, thereby drastically improving the enforcement capacities of existing international rules (Österblom and Sumaila 2011).

International actors trying to prepare for the possibly harmful human well-being implications of ocean acidification and rapid loss of marine biodiversity, also illustrate this triad. As these actors perceive the possible transgression of human–environmental “tipping points” (incentives), they coordinate their actions in global networks to increase their opportunities to bring additional issues to existing policy arenas created by international institutions (adaptability). At the same time, these institutions fundamentally affect the biophysical, technological, and social drivers that affect the “tipping points” at hand (interplay, e.g., the Convention on Biological Diversity, climate change agreements under the UNFCCC, and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea).

The analysis is only tentative of course, especially considering the small number of cases, the contested nature of “tipping points,” and the need to explore additional working propositions. For example, we have not elaborated the cognitive and leadership processes leading up to a joint problem definition among the collaborating actors, nor a number of associated issues such as transparency and accountability in complex actor settings.

However, the analysis brings together a number of theoretically and empirically founded propositions worth further attention. More precisely, how state and non-state actors perceive and frame global change-induced “tipping points,” the unfolding global network dynamics, and how these are shaped by international institutions (Fig. 3) remain an interesting issue to explore further by scholars interested in the governance of a complex Earth system.

Notes

See below for a more detailed discussion and references.

http://www.oceansatlas.org/www.un-oceans.org/Documents/tf_pacfa_tor.pdf. Accessed 2012-05-21.

References

Adger, W. N., Eakin, H., & Winkels, A. (2009). Nested and teleconnected vulnerabilities to environmental change. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 7, 150–157.

Agnew D. J. et al. (2009). Estimating the world-wide extent of illegal fishing. PLoS ONE, 4. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004570.

Ansell, C. (2006). Network institutionalism. In R. A. W. Rhodes, S. A. Binder, & B. A. Rockman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political institutions (pp. 75–89). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baird, R. (2004). Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing: an analysis of the legal, economic and historical factors relevant to its development and persistence. Melbourne Journal of International Law, 13, 299–335.

Balkundi, P., & Kilduff, M. (2006). The ties that lead: A social network approach to leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(4), 419–439.

Barrett, S., & Dannenberg, A. (2012). Climate negotiations under scientific uncertainty. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(43), 17372–17376.

Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 611–639.

Biermann, F. (2007). ‘Earth system governance’ as a crosscutting theme of global change research. Global Environmental Change, 17(3–4), 326–337.

Biermann, F. (2012). Planetary boundaries and earth system governance: Exploring the links. Ecological Economics, 81, 4–9.

Biermann, F., Abbott, K., Andresen, S., et al. (2012). Navigating the anthropocene: Improving earth system governance. Science, 335, 1306–1307.

Biermann, Frank., & Pattberg, Philipp. (2012). Global environmental governance reconsidered. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bodin, Ö., & Crona, B. (2009). The role of social networks in natural resource governance: What relational patterns make a difference? Global Environmental Change, 19, 366–374.

Bodin, Ö., & Prell, C. (2011). Social networks and natural resource management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boin, A., ‘t Hart, P., Stern, E., & Sundelius, B. (2005). The politics of crisis management—Public leadership under pressure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brook, B.W., Ellis, E. C., Perring, M. P., Mackay, A. W., & Blomqvist, L. (2013). Does the terrestrial biosphere have planetary tipping points? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.016.

Campbell, J. L. (2002). Ideas, politics, and public policy. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 21–38.

Cash, D., Adger, N. W., Berkes, F., et al. (2006). Scale and cross-scale dynamics: Governance and information in a multilevel world. Ecology and Society, 11(2), 8.

Chan, E. H., et al. (2010). Global capacity for emerging infectious disease detection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(50), 21701–21706. 10.1073/pnas.1006219107.

Claessens, S., Dell’Ariccia, G., Igan, D., & Laeven, L. (2010). Cross-country experiences and policy implications from the global financial crisis. Economic Policy, 25(62), 267–293.

Comfort, L. K. (1988). Designing policy for action: The emergency management system. In L. K. Comfort (Ed.), Managing disaster: Strategies and policy perspectives (pp. 3–21). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Constable, A. J., de la Mare, W. K., Agnew, D. J., Everson, I., & Miller, D. G. M. (2010). Managing fisheries to conserve the Antarctic marine ecosystem: Practical implementation of the convention on the conservation of Antarctic Marine living resources (CCAMLR). ICES Journal of Marine Science, 57(3), 778–791.

Cox, et al. (2000). Acceleration of global warming due to carbon-cycle feedbacks in a coupled climate model. Nature, 408(6809), 184–187.

Cross, M. K. D. (2012). Rethinking epistemic communities twenty years later. Review of International Studies, 39(01), 137–160.

Curley, M. G., & Herington, J. (2011). The securitisation of avian influenza: International discourses and domestic politics in Asia. Review of International Studies, 37(1), 141–166.

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E., & Stern, P. C. (2003). The struggle to govern the commons. Science, 302(5652), 1907–1912.

Dimitrov, R. S., Sprinz, D. F., DiGiusto, G. M., & Kelle, A. (2007). International nonregimes: A research agenda. International Studies Review, 9, 230–258.

Dodds, P. S., Watts, D. J., & Sabel, C. F. (2003). Information exchange and the robustness of organizational networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(21), 12516–12521.

Downs, G. W. (2000). Constructing effective environmental regimes. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 25–42.

Dry, S., & Leach, M. (2010). Epidemics—Science. Earthscan: Governance and Social Justice.

Duit, A., & Galaz, V. (2008). Governance and complexity—Emerging issues for governance theory. Governance, 21(3), 311–335.

Edelenbos, J., Van Buuren, A., & Klijn, E.-H. (2013). Connective capacities of network managers. Public Management Review, 15(1), 131–159.

Emirbayer, M., & Goodwin, J. (1994). Network analysis, culture, and the problem of agency. American Journal of Sociology, 99, 1411–1454.

Fallon, L., & Kriwoken, K. (2004). International influence of an Australian nongovernment organization in the protection of Patagonian toothfish. Ocean Development & International Law, 35, 221–266.

FAO (2005) Report of the Technical consultation to review progress and promote the full implementation of the international plan of action to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and the international plan of action for the management of fishing capacity. FIPL/R753. FAO Fisheries Report No. 753, FAO, Rome.

Fidler, D. (2004). SARS, Governance and the Globalization of Disease. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fidler, D. (2008). Influenza virus samples, international law, and global health diplomacy. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 14(1), 88–94.

Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P., & Norberg, J. (2005). Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 30, 441–473.

Galaz, V. (2009). Pandemic 2.0: Can information technology really help Us save the planet?”. Environment, 51(6), 20–28.

Galaz, V. (2011). Double complexity—Information technology and reconfigurations in adaptive governance. In E. Boyd & C. Folke (Eds.), Adapting institutions—Governance, complexity and social-ecological resilience (pp. 193–215). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Galaz, V. (2014). Global environmental governance, technology and politics: The Anthropocene gap. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Galaz, V., Biermann, F., Crona, B., et al. (2012). Planetary boundaries—exploring the challenges for global environmental governance. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 4(1), 80–87.

Galaz, V., Crona, B., Daw, T., Bodin, Ö., Nyström, M., & Olsson, P. (2010a). Can web crawlers revolutionize ecological monitoring? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 8, 99–104.

Galaz, V., Crona, B., Österblom, H., Olsson, P., & Folke, C. (2011). Polycentric systems and interacting planetary boundaries: Emerging governance of climate change–ocean acidification–marine biodiversity. Ecological Economics, 81, 21–32.

Galaz, V., Hahn, H., Olsson, P., Folke, C., & Svedin, U. (2008). The problem of fit between ecosystems and governance systems: Insights and emerging challenges. In O. Young, L. A. King, & H. Schroeder (Eds.), The institutional dimensions of global environmental change: principal findings and future directions (pp. 147–186). Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Galaz, V., Moberg, F., Olsson, E. K., Paglia, E., & Parker, C. (2010b). Institutional and political leadership dimensions of cascading ecological crises. Public Administration, 89(2), 361–380.

Gardiner, S. M. (2009). Saved by disaster? Abrupt climate change, political inertia, and the possibility of an intergenerational arms race. Journal of Social Philosophy, 40(2), 140–162.

Gehring, T., & Oberthür, S. (2009). The causal mechanisms of interaction between international institutions. European Journal of International Relations, 15(1), 125–156.

Gerring, J. (2004). What is a case study and what is it good for? American Political Science Review, 98(2), 341–354.

Gullett, W., & Schofield, C. (2007). Pushing the limits of the law of the sea convention: Australian and French cooperative surveillance and enforcement in the Southern Ocean. International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law, 22, 545–583.

Haas, P. M. (1992). Banning chlorofluorocarbons: epistemic community efforts to protect stratospheric ozone. International Organization, 46(1), 187–224.

Heymann, D. L. (2006). SARS and emerging infectious diseases: A challenge to place global solidarity above national sovereignty. Annals Academy of Medicine Singapore, 35, 350–353.

Hoegh-Guldberg, O., et al. (2007). Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science, 318(5857), 1737–1742.

Holling, C. S. (1978). Adaptive environmental assessment and management. Chichester: Wiley.

Hoppe, B., & Reinelt, C. (2010). Social network analysis and the evaluation of leadership networks. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(4), 600–619.

Hulme, M. (2012). On the two degrees climate policy target. In O. Edenhofer, J. Wallacher, H. Lotze-Campen, M. Reder, B. Knopf & J. Müller (Eds.), Climate change, justice and sustainability: Linking climate and development policy, (pp. 122–125). Dordrecht: Springer.

Hutchings, J. A., & Reynolds, J. D. (2004). Marine fish population collapses: Consequences for recovery and extinction risk. BioScience, 54(4), 297–309.

IOM (Institute of Medicine) and National Research Council (NRC). (2008). Achieving sustainable global capacity for surveillance and response to emerging diseases of zoonotic origin: Workshop report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jessop, B. (1998). The rise of governance and the risks of failure: The case of economic development. International Social Science Journal, 50(155), 29–45.

Kanie, N., Betsill, M. M., Zondervan, R., et al. (2012). A charter moment: Restructuring governance for sustainability. Public Administration and Development, 32, 292–304.

Kinzig, A. P., Ryan, P., Etienne, M., et al. (2006). Resilience and regime shifts: Assessing cascading effects. Ecology and Society, 11(1), 20.

Knopf, B., Flachsland, C., & Edenhofer, O. (2012). The 2C target reconsidered. In O. Edenhofer, J. Wallacher, H. Lotze-Campen, M. Reder, B. Knopf, & J. Müller (Eds.), Climate change, justice and sustainability: Linking climate and development policy (pp. 121–137). Dordrecht: Springer, Netherlands.

Koppenjan, J., & Klijn, E.-H. (2004). Managing uncertainties in networks: A network approach to problem solving and decision making. New York: Routledge.

Lenton, T. M., Held, H., Kriegler, E., et al. (2008). Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105, 1786–1793.

Low, B., Ostrom, E., Simon, C., & Wilson, J. (2003). Redundancy and diversity: Do they influence optimal management? In Fikret. Berkes, Johan. Colding, & Carl. Folke (Eds.), Navigating social-ecological systems—Building resilience for complexity and change (pp. 83–114). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lynam, T., & Brown, K. (2011). Mental models in human-environment interactions: Theory, policy implications, and methodological explorations’. Ecology and Society, 17(3), 24.

Milkoreit, M. (2013). Mindmade politics: The role of cognition in global climate change governance. Ph.D. Thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Global Governance.

Miller, D. G., Slicer, N., & Sabourenkov, E. (2010). IUU fishing in antarctic waters: CCAMLR actions and regulations. In D. Vidas (Ed.), Law, technology and science for oceans in globalization (pp. 175–196). Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Mitchell, R. B. (2002). A quantitative approach to evaluating international environmental regimes. Global Environmental Politics, 2(4), 58–83.

Monge, P. R., & Contractor, N. S. (2003). Theories of communication networks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moynihan, D. (2008). Learning under uncertainty: Networks in crisis management. Public Administration Review, 68(2), 350–361.

Oberthür, S., & Stokke, O. S. (2011). Managing institutional complexity—Regime interplay and global environmental change. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

OECD. (2011). Future Global Shocks—Improving Risk Governance. OECD Reviews of Risk Management Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Orsini, A., Morin, J., & Young, O. (2013). Regime complexes: A buzz, a boom, or a boost for global governance? Global Governance, 19, 27–39.

Österblom, H., & Bodin, Ö. (2012). Global cooperation among diverse organizations to reduce illegal fishing in the Southern Ocean. Conservation Biology, 26(4), 638–648.

Österblom, H., Constable, A., & Fukumi, S. (2011). Illegal fishing and the organized crime analogy. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 26, 261–262.

Österblom, H., & Sumaila, U. R. (2011). Toothfish crises, actor diversity and the emergence of compliance mechanisms in the Southern Ocean. Global Environmental Change, 21, 972–982.

Österblom, H., et al. (2010). Adapting to regional enforcement: Fishing down the governance index. PLoS ONE, 5, e12832.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Pahl-Wostl, Claudia. (2009). A conceptual framework for analyzing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global Environmental Change, 19, 345–365.

Pauly, D., Alder, J., Bennett, E., Christensen, V., Tyedmers, P., & Watson, R. (2003). The future for fisheries. Science, 302, 1359–1361.

Pearson, C. M., & Clair, J. A. (1998). Reframing crisis management. Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 59–76.

Plummer, R., Crona, B., Armitage, D. R., Olsson, P., & Yudina, O. (2012). Adaptive comanagement: A systematic review and analysis, Ecology and Society, 17(3), 11. doi:10.5751/ES-04952-170311.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K. et al. (2009b) Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society, 14(2): 32. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., et al. (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461, 472–475.

SC-CAMLR (Scientific Committee for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources). (1997). Report of the sixteenth meeting of the scientific committee. Hobart: SC-CAMLR.

SC-CAMLR (Scientific Committee for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources). (2002). Report of the twenty-first meeting of the scientific committee. Hobart: SC-CAMLR.

Scheffer, M., Bascompte, J. B., Brock, W. A., et al. (2009). Early-warning signals for critical transitions. Nature, 461(7260), 53–59.

Scheffer, M., & Carpenter, S. R. (2003). Catastrophic regime shifts in ecosystems: Linking theory to observation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 18(12), 648–656.

Schlesinger, W. H. (2009). Planetary boundaries: Thresholds risk prolonged degradation. Nature Reports Climate Change, 3(0910), 112–113.

Steffen, W., Persson, Å., Deutsch, L., et al. (2011). The anthropocene: From global change to planetary stewardship. Ambio, 40, 739–761.

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610.

Swartz, W., Sala, E., Tracey, S., Watson, R., & Pauly, D. (2010). The spatial expansion and ecological footprint of fisheries (1950 to Present). PLoS ONE, 5(12), e15143. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015143.

UN-FSA. (1995). The United Nations agreement for the implementation of the provisions of the United Nations convention on the law of the sea of 10 December 1982 relating to the Conservation and management of straddling fish stocks and highly migratory fish stocks. United Nations General Assembly, New York.

van Baalen, P. J., & van Fenema, P. C. (2009). Instantiating global crisis networks: The case of SARS. Decision Support Systems, 47(4), 277–286.

van Kersbergen, K., & van Waarden, F. (2004). “Governance” as a bridge between disciplines: Cross-disciplinary inspiration regarding shifts in governance and problems of governability, accountability and legitimacy. European Journal of Political Research, 43, 143–171.

Walker, B., Barrett, S., Polasky, S., et al. (2009). Looming global-scale failures and missing institutions. Science, 325(5946), 1345–1346.

Walker, B. H., Gunderson, L., Kinzig, A. et al (2006). A handful of heuristics and some propositions for understanding resilience in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 11(1): 13. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art13/.

Wallinga, J., & Teunis, P. (2004). Different epidemic curves for severe acute respiratory syndrome reveal similar impacts of control measures. American Journal of Epidemiology, 160(6), 509–516.

WHO. (2005). WHO global influenza preparedness plan—The role of WHO and recommendations for national measures before and during pandemics. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Winter, G. (Ed.). (2006). Multilevel governance of global environmental change—Perspectives from science, sociology and the law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

World Economic Forum. (2013). Global risks 2013 (8th ed.). Geneva: Switzerland.

Young, O. R. (2008). Building regimes for socioecological systems. In O. R. Young, L. A. King & H. Schroeder (Eds.), The institutional dimensions of global environmental change: Principal findings and future directions (pp. 115–144). Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Young, O. R. (2010). Institutional dynamics: Resilience, vulnerability and adaptation in environmental and resource regimes. Global Environmental Change, 20(3), 378–385.

Young, O. R. (2011). Effectiveness of international environmental regimes: Existing knowledge, cutting-edge themes, and research strategies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 4, 1–8.

Zarocostas, J. (2011). WHO processes on dealing with a pandemic need to be overhauled and made more transparent. BMJ, 2011, 342. doi:10.1136/bmj.d3378.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Mistra through a core grant to the Stockholm Resilience Centre, a cross-faculty research centre at Stockholm University, and through grants from the Futura Foundation. H. Ö. was supported by Baltic Ecosystem Adaptive Management (BEAM) and the Nippon Foundation. Ö. B. was supported by the strategic research program Ekoklim at Stockholm University. B. C. was supported by the Erling-Persson Family Foundation. We are grateful to colleagues at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, and to Oran Young, Ruben Zondervan and Sarah Cornell for detailed comments on early drafts of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Appendices

Appendix 1: data for visualization of global networks

Figure shows key members in each respective network, including the type (state/governmental, non-state actor, international organization).

Data: Global epidemic networks based on WHO database on collaborating partners for outbreak and emergencies (http://apps.who.int/whocc/Default.aspx), OIE/FAO Network of expertise on animal influenza (http://www.offlu.net/index.php?id=76), European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (http://www.ecdc.eu), the US CDC Influenza Division International Program (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International Influenza Report FY 2010. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010), and Medecins Sans Frontieres (http://www.msf.org/msf/countries/countries_home.cfm). It should be noted, however, that there are additional networks involved in global epidemic preparedness and response depending on the location and disease of interest.

Pacfa is based on official Web page (http://www.climatefish.org/index_en.htm) and Galaz et al. 2011.

The network around IUU fishing in the CCAMLR area is based on Österblom and Sumaila (2011). Note that not all members of CCAMLR http://ccamlr.org/pu/e/ms/contacts.htm are actively engaged in reducing IUU fishing as this is an organization tasked with multiple issues related to natural resources in the Southern Ocean.

Appendix 2: summary of case studies and template for data collection

Here, we briefly summarize the case studies and the protocol for data collection. Data have been collected through semi-structured interviews, literature reviews, and surveys (see individual articles for details, i.e., Galaz 2011, Galaz et al. 2010b, Österblom and Sumaila 2011, Österblom and Bodin 2012, Österblom et al. 2011). All cases used the same methodology, combining document studies, simple network analysis, and semi-structured interviews with key international actors (a total of about 65 interviews for all cases). Interviewees have been selected strategically to reflect an expected diversity of interests, resources, and role in the network collaboration of interest. The material has been structured and complemented with additional published and “gray” literature to elaborate the five overarching subjects below. These five subjects were identified during a series of author workshops and aimed to provide a structured overview of the perception of the problem to be addressed, the emergence of the network studied, as well as its function, effectiveness, and perceived legitimacy. Original data sources and detailed methods are available in the literature cited.

2.1 Subject

-

(1)

What is the risk of a global change-induced “tipping point”?

-

a.

What is the “tipping point” of interest?

-

b.

Over which time frame does it operate and what is the response capacity required?

-

c.

What social and ecological uncertainties exist?

-

d.

What underlying social and ecological mechanisms increase the risk of “tipping point” behavior?

-

a.

-

(2)

Why is global coordination needed?

-

(3)

How did the global network emerge and evolve?

-

a.

How did the network emerge?

-

b.

Which key actors/organizations were responsible for this development?

-

c.

What existing networks/governance features did these actors/organizations build on?

-

d.

How did the network develop over time and what is the current trajectory (how is capacity maintained and developed)?

-

e.

In what political context did the network emerge and develop?

-

f.

To what extent were they supported, or counteracted by state actors and/or other institutions?

-

g.

How is it coordinated (and what are the pros and cons of coordination)?

-

h.

What framework (legal or otherwise) is regulating network activities (and what are the pros and cons with the framework/lack of framework)?

-

i.

How are transparency issues addressed?

-

j.

What is known about the perceived legitimacy, fairness, and biases of the network?

-

k.

What are the primary tools of action for the network?

-

a.

-

(4)

How is monitoring, sense-making, and coordinated responses enabled?

-

a.

What are the monitoring capacities of the network (is both ecological and social monitoring conducted)?

-

b.

How does the network achieve sense-making around “tipping points”?

-

c.

How does the network enable rapid and coordinated responses?

-

d.

What role does information and communication technologies play in monitoring, sense-making, and response?

-

e.

What are major barriers for a continued evolution of the network?

-

a.

-

(5)

What outputs and outcomes can be attributed to the network?

-

a.

What are the major outputs from the network?

-

b.

What are the most important outcomes from the network?

-

a.

Case 1. Pacfa: global partnership on climate, fisheries, and aquaculture

3.1 Summary

Oceans capture approximately one-third of anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases. This process is changing ocean chemistry, making oceans more acidic, with potentially enormous negative consequences for a wide range of marine species and societies as a result of losses of ecosystem services. Recent research suggests that ocean acidification is likely to exhibit critical “tipping points” associated with rapid loss of coral reefs, as well as complex ocean–climate interactions affecting the oceans’ capacities to capture carbon dioxide. The global arena for addressing these interrelated aspects of marine governance is characterized by a lack of effective coordination among the policy areas of marine biodiversity, fisheries, climate change, and ocean acidification. This has stimulated an attempt to better bridge these policy domains to increase coordination aimed at addressing potential critical tipping points. A number of international organizations primarily involved in fisheries initiated the Global Partnership on Climate, Fisheries, and Aquaculture (from hereon Pacfa) in 2008. Currently, this initiative includes representatives from FAO, UNEP, WorldFish, The World Bank, and 13 additional international organizations (Fig. 1). Joint outputs include synthesizing information as a way to monitor the status of unfolding nonlinear dynamics, dissemination of information in science-policy workshops, and lobbying international arenas.

-

1a.