Abstract

Teachers play a critical role in facilitating the career and life planning of secondary school students. This paper describes the development of the Career-Related Teacher Support Scale (Hong Kong Secondary Students Form). Based on data obtained from 493 students in Hong Kong, five types of career-related teacher support were identified with the most important form of support being teachers’ knowledge about the world of work and study path requirements. A correlation model yielded the best fit to the data. No variance in response pattern appeared across genders, and the new scale was found to have good validity and reliability.

Résumé

Enquête sur le soutien des enseignant·e·s lié à la carrière pour les étudiant·e·s chinois du secondaire à Hong Kong

Les enseignant·e·s jouent un rôle essentiel en facilitant la planification de la carrière et de la vie des élèves du secondaire. Cet article décrit le développement de l'échelle Career-Related Teacher Support Scale (Hong Kong Secondary Students Form). Sur la base des données obtenues auprès de 493 étudiantes à Hong Kong, cinq types de soutien des enseignantes liés à la carrière ont été identifiés, la forme de soutien la plus importante étant les connaissances des enseignantes sur le monde du travail et les exigences des filières d'études. Un modèle de corrélation s'est avéré le mieux adapté aux données. Aucune variance dans le modèle de réponse n'est apparue entre les sexes, et la nouvelle échelle s'est avérée avoir une bonne validité et fiabilité.

Zusammenfasung

Untersuchung der berufsbezogenen Unterstützung durch Lehrer für chinesische Sekundarschüler in Hongkong

Lehrer spielen eine entscheidende Rolle bei der Unterstützung der Berufs- und Lebensplanung von Sekundarschülern. Dieser Beitrag beschreibt die Entwicklung der Skala zur berufsbezogenen Lehrerunterstützung (Hong Kong Secondary Students Form). Auf der Grundlage von Daten, die von 493 Schülern in Hongkong erhoben wurden, wurden fünf Arten der berufsbezogenen Unterstützung durch Lehrer identifiziert, wobei die wichtigste Form der Unterstützung das Wissen der Lehrer über die Arbeitswelt und die Anforderungen von Studiengängen ist. Ein Korrelationsmodell ergab die beste Übereinstimmung mit den Daten. Zwischen den Geschlechtern traten keine Unterschiede im Antwortmuster auf. Die neue Skala hat eine gute Validität und Zuverlässigkeit.

Resumen

Investigando el Apoyo Docente al Desarrollo de la Carrera para estudiantes chinos de secundaria en Hong Kong

Los profesores desempeñan un papel fundamental a la hora de facilitar la planificación de la carrera y la vida de los estudiantes de secundaria. Este artículo describe el desarrollo de la Escala de Apoyo Docente al Desarrollo de la Carrera (Cuestionario para Estudiantes de Secundaria de Hong Kong). Sobre la base de los datos obtenidos de 493 estudiantes en Hong Kong, se identificaron cinco tipos de apoyo de los docentes relacionados con la carrera, siendo la forma más importante de apoyo el conocimiento de los docentes sobre el mundo del trabajo y los requisitos de las trayectorias educativas. El mejor ajuste para los datos fue aportado por un modelo de correlación. No apareció ninguna variabilidad en el patrón de respuesta relacionada con el género, y se encontró que la nueva escala tiene buena validez y fiabilidad.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is generally accepted in secondary schools worldwide that support from significant others is vitally important to assist adolescents’ personal development, especially with regard to career-path planning and preparation (Jimerson & Haddock, 2015; Perry et al., 2010). Research (mainly conducted in the West) has explored the role of general support from teachers. However, researchers have tended to focus predominantly on support for students’ academic development, rather than for career planning (Chong et al., 2018; Datu & Yang, 2019; Kingsbury et al., 2020; Samuel & Burger, 2020). There is also a significant lack of information on this topic in relation to Hong Kong and other areas of China. The literature has revealed that virtually no data collection instruments have been culturally adapted to assess which types of teacher support Chinese secondary school students find beneficial to their career development (Metheny et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2021). Much less is known therefore about teacher support for students’ career development in non-Western cultural settings (Gysbers, 2000; Yuen et al., 2003). The purpose of this study was to address this lack of data by creating a Chinese version of the Career-Related Teacher Support Scale (CRTSS), using data from a target group of secondary students in Hong Kong.

The scale, hereafter referred to as the CRTSS-HKSS, was trialled and validated with a sample of Hong Kong Chinese senior secondary students (Grades 10–12; age range: 14–20). It is helpful to know which forms of support are most valued by students, and whether such support is being provided in a particular setting. The developed scale provides a useful tool that strengthens the support that school-based career guidance and counselling services in Hong Kong can provide in the career development domain.

This study is timely given that students face uncertainties in career planning as the world of work has been severely affected not only by rapid advances in technology (Hirschi, 2018; Stebleton & Kaler, 2020) but also by the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. As in many other places around the world, the unemployment rate in Hong Kong is now at a record high (Moody’s Analytics, 2020), so the role played by secondary school teachers in supporting their students has never been more vital. It is imperative to identify actions that can facilitate students’ career planning and reduce anxiety and feelings of hopelessness (Blustein et al., 2020; World Bank Group Jobs, 2020).

Relationship between teacher support and adolescents’ career development

It is not surprising that teacher support of all kinds is instrumental in facilitating a student’s overall development and well-being. After all, adolescents spend a great deal of their time at school (Chong et al., 2018; Hamre & Pianta, 2010). Teachers are in an excellent position to provide support, but they need to know the appropriate form of support to give for students’ specific needs. The most important form of social support from any adult (including teachers) is unconditional acceptance, which leads individuals to believe that they are cared for and valued and ultimately leads to autonomy (Schwarzer & Buchwald, 2004).

A meta-analysis by Lei et al. (2018) found three other types of support namely providing useful information that assists students in planning and decision-making, instrumental support (direct help for a particular matter), and appraisal support that constructively lets students know how they are performing and how to set new goals. Teacher support has also been found to relate to several positive student developmental outcomes, including school adjustment (Zee et al., 2013), higher rates of school completion (Burns, 2020), and higher levels of motivation to pursue life goals (Hattie, 2009; Locke & Latham, 2019; Morisano et al., 2010).

In the specific domain of career guidance in schools, social support from adults has been found to be linked to students’ positive career exploration behaviour and expectations (Di Fabio & Kenny, 2012). This link between support and career planning is predicted by social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 2000), the principles of which suggest that social support strengthens motivation and goal-setting. Social support is also hypothesised to offer protection against negative influences such as feelings of hopelessness and depression (Beck et al., 1974; Boysan, 2020; Dieringer et al., 2017). Hopelessness is regarded as an emotional state that impedes the formation of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1999) and thus creates a lack of personal control over career planning and job seeking (Ulas & Yildirim, 2019). Given the hopelessness that some senior students experience when seeking employment today, this support from teachers is extremely important and potentially powerful.

According to Zhang et al. (2018), career-related teacher support (CRTS) has both general and specific forms. General support relates to students’ academic work, extracurricular pursuits, and personal matters, while specific support targets specific issues, such as career planning. The relative importance of these two forms of support depends somewhat on grade level and type of school (Zhang et al., 2020). In secondary schools, teachers who are in any way associated with career guidance must be willing and able to perform several supportive roles (Wong et al., 2020). First, teachers should act as caregivers who are genuinely concerned with meeting their students’ diverse career-planning needs. Second, teachers must take steps to foster students’ career self-efficacy and positive self-concept. Third, teachers must endeavour to encourage their students to have positive career aspirations and motivate them to strive towards their personal career goals.

Research has suggested that CRTS is linked to adolescents’ development in terms of work readiness (Phillips et al., 2002), exploration (Kenny et al., 2003), decision-making (Michaeli et al., 2018), preparation (Perry et al., 2010), and adaptability (Hui et al., 2018). CRTS also helps students choose their university major (Wang, 2013). One specific feature of teacher support that appears to facilitate students’ career decision-making is the provision of relevant and timely career and employment information (OECD, 2004; Zhang et al., 2018). This suggests that teachers in secondary schools must stay up-to-date with the local employment situation and keep abreast of university requirements for specific career paths (Alexander et al., 2019; Hirschi, 2012). When this information is not available, problems are created for students who need to make important career decisions (OECD, 2004; Watts, 2013).

Evaluating career-related teacher support

A review of the field by Zhang et al. (2018) identified a significant lack of instruments suitable for investigating CRTS. Most of the published scales were developed in the West and were not designed specifically to assess career-related support. These scales are therefore rarely suitable for use in research into teacher support for the career development of students in the East (Suldo et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2021). Among the few published measures dedicated solely to the measurement of CRTS, the Teacher Support Scale (TSS; Metheny et al., 2008) is the most frequently cited and has been shown to have good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .96) (Zhang et al., 2018). However, it is important to note that teachers’ contribution in providing employment information is not assessed by the TSS. This would seem to be a serious omission given the value of such information for students’ career decision-making (Finnish Youth Barometer, 2017; Gati & Kulcsár, 2021).

To address this weakness of the TSS, Zhang et al. (2021) developed the CRTSS, which includes informational support. The 16-item CRTSS was subjected to factor analyses and showed excellent properties (comparative fit index [CFI] = .981, Tucker–Lewis index [TLI] = .975, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .050). The scale also demonstrated excellent reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha values of .90 to .92 across the three factors identified. Measurement invariance across genders was also evident. One limitation of the scale is that it was only validated with a sample of technical education students in mainland China, so the content may not be entirely appropriate for senior secondary school students in Hong Kong.

Marciniak et al. (2021) developed a different type of instrument—the Career Resources Questionnaire—to investigate adolescents’ ability to access different types of psychological and other resources to facilitate their career development. This questionnaire assesses general school support for career guidance, rather than teacher support, and does not include informational support. The items were developed based on a review of the literature rather than direct observation of students’ needs or use of resources and therefore may not fully address the real career guidance needs of adolescents in schools (Lavik et al., 2018; Moyer & Goldberg, 2020).

The purpose of this study was to develop a Chinese version of the CRTSS (Hong Kong Secondary Students form: CRTSS-HKSS) to evaluate CRTS in the Hong Kong secondary school context and to determine the scale’s structure, internal consistency, and measurement invariance.

Study Location and Context

In Hong Kong, the three supportive roles described above for teachers—caregiver, fosterer of students’ career self-efficacy, and motivator—are understood and enacted with varying degrees of success (Wong et al., 2020). While career guidance is accepted as important, teachers in Hong Kong remain preoccupied with students’ success in high-stakes public exams. This is due to the deeply entrenched belief that performing well in public examinations is the only path to good career development outcomes (Leung & Shek, 2011; Shek & Wu, 2016). The pressure to succeed in high-stakes university entrance examinations is so great that it has resulted in psychological stress and even suicidal ideation among secondary school students (Lee et al., 2006). Students who fail to gain entry to reputable universities often see themselves as ‘losers’ who are going to have a hopeless future (Tsang et al., 2021). This explains why many teachers in Hong Kong feel that it is more important to invest their time in academic support rather than devoting time to students’ career planning (Ho & Leung, 2016; Williams, 1973; Wong, 2017). Despite the importance of one-to-one career counselling, it is not common for Hong Kong secondary schools to provide such sessions for their students. This is mainly due to teachers’ busy schedules for teaching and managing other issues such as students’ academic progress, as well as attending to behavioural and emotional problems (Leung et al., 2002; Tsang, 2018).

Teachers in Hong Kong also find it difficult to obtain up-to-date information about specific types of employment in the current job market because they have spent most of their professional lives working in schools as teachers. They possess little or no experience in other occupational fields. The advice they provide is therefore usually limited to academic advising and is not job specific (Yang & Wong, 2020). To compensate for their lack of direct knowledge and experience, secondary school teachers in Hong Kong typically rely on inviting guest speakers from the business sector to deliver talks to disseminate career information (Wong et al., 2019). This approach is inadequate to address the concerns of individual students, and students themselves have reported that ‘one off’ mass sessions are not very useful in facilitating their career planning (Tsui et al., 2019).

Another area of weakness in career guidance in Hong Kong is that there are no statutory requirements governing the qualifications and training requirements of persons performing careers work in secondary schools and there are no quality assurance mechanisms that are comparable to international standards (Leung, 2002; Leung et al., 2007). Currently, only short training courses are available for teachers and they tend to address theoretical aspects of career guidance and counselling with no supervised practicum component (Wong & Yuen, 2019). In addition, these courses are generally taught by personnel who have no extensive training in career counselling and who have had little or no prior experience working in occupational fields other than education (Wong, 2018).

Recent studies conducted in Hong Kong have found deficiencies in career guidance and counselling in secondary schools. A territory-wide survey in 2019, involving more than 700 young people from 103 secondary schools, found that up to 30% of the students reported that their teachers had provided little or no support to encourage their career planning and exploration (Federation of Youth Groups, 2019). Another study conducted by Yuen et al. (2020) found that only 2.6% of the 4,850 students surveyed named their career guidance teachers as their most important source of career advice and support.

Some of these deficiencies could be related to the traditions and cultural influences prevailing in Hong Kong schools. The principles, practices, and priorities for career guidance and counselling tend to be different in different countries and regions (Arthur & Collins, 2011). Due to Hong Kong’s unique history as a former British colony, people in the region have greater access to Western ideologies than residents of other regions of China do (Chow et al., 2020; Postiglione & Leung, 1991). However, in Hong Kong, teachers and parents still tend to apply traditional notions of what schools should teach and the qualities students should display. Their conceptualisation of what constitutes an ideal student still resembles the typical Chinese belief that students should be academic high achievers who are hardworking, motivated, humble, obedient, respectful, and self-disciplined (Lam, 1996). Secondary school teachers in particular are expected simply to teach well, keep their students under control, and maintain a social distance from their students (Salili et al., 2001). This creates a situation in which it is extremely difficult for the average teacher to provide close personal counselling and individualised support (Bray & Koo, 2005; Ryan & Louie, 2013; Wong et al., 2020).

It is against this background that a new instrument for evaluating CRTS in a Hong Kong Chinese context was created.

General method

Item development

The first step in developing the new instrument was to review the literature on adolescent career development, social support, and school psychology to gain insights into the types of items that should be included in the questionnaire. Senior secondary students were then recruited to provide perceptions of the career-related support they had received at school and the usefulness of such support for their career planning. Four focus groups were conducted, involving 30 Chinese secondary students (10 male students; 20 female students) from public secondary schools in Hong Kong. The students had different levels of academic ability and were reasonably representative of the typical secondary school population. The focus group discussions were essential to supplement the information from the literature (Lynass et al., 2012). A teacher with more than 20 years of experience in guidance and counselling in secondary schools in Hong Kong independently reviewed the themes generated from the focus group data. Six themes emerged that characterised CRTS: providing information, giving emotional support, encouraging student autonomy, providing honest appraisal, encouraging motivation, and ease of access to teachers (Wong et al., 2021).

Based on these six themes, a first draft of the new scale containing 42 items was created. The items were drafted in English because that is the language of instruction used in most academic institutions in Hong Kong. The questionnaire was then translated into Chinese before trialling the instrument with students. The design of the scale was also influenced to some extent by previously published scales (e.g. Metheny et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2021).

Before piloting the scale, the items in English and Chinese were checked by two experts proficient in both languages and who had experience of student counselling in Hong Kong. As an additional check, the first author gathered a group of secondary school students who were not related to this study to assess the clarity of each item. Some minor adjustments were made to the wording of a few the items and some items were deleted. The final draft contained 37 items. Exploratory factor analysis was then performed to explore the factor structure of the scale (Study 1). The refined scale was then deployed again to confirm its factor structure and to determine to what extent the various forms of CRTS were associated with students’ career development self-efficacy and hopelessness (Study 2).

Research ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the university before data collection. The objectives, the design of the instrument, and the data collection and analysis strategies were clearly described in the consent forms. Written permission to perform the research was also obtained from the principals of the participating schools. The data collection process was performed by individuals who had received prior training.

Study 1: exploratory factor analysis

Method

Participants

The participants in Study 1 were 493 students in Secondary 4, 5, or 6 (Grades 10, 11, or 12) from two schools in Hong Kong selected randomly from the Education Bureau’s list of secondary schools. Both schools were publicly subsidised secondary schools with a religious background. The students were all native Chinese and aged 14 to 19 (mean age = 16.02 years; SD = .98). The sample contained more female than male students (72.2%), which occurred by chance but mirrors the population in Hong Kong (Census & Statistics Department, 2020; Parvazian et al., 2017).

Measures

The 37-item draft Chinese version of the CRTSS-HKSS was administered to assess the types of career support from teachers that students perceive to be useful in enhancing their career development. The scale used a 5-point Likert-type response format, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) for the perceived frequency of each type of support. An example item is ‘My teachers are interested in my future’. The participants also reported their age and gender on the questionnaire and were asked to rate their own academic ability on a 5-point Likert-type scale, from 1 (bottom 10%) to 5 (top 10%).

Results

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted using principal axis factoring. Promax (oblique) rotation was used for factor rotation because it was anticipated that the underlying factors would be correlated to form a unitary measurement of CRTS (Reise et al., 2000). As noted above, the problem of missing data was addressed using the maximum likelihood method (Schlomer et al., 2010). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was .890, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < .001), indicating that the sample was suitable for factor analysis (Tabachnick & Fidel, 2007).

Several criteria were used to determine how many factors to retain: (a) initial eigenvalues (> 1), (b) scree plot analysis, (c) Velicer’s minimum average partial test (MAP), and (d) parallel analysis (Horn, 1965). Seven factors were initially identified by examining the eigenvalues and the scree plot. Parallel analysis suggested a five-factor solution, while MAP suggested a four-factor solution. The five-factor model was adopted because parallel analysis is considered to be one of the most reliable methods to determine the number of factors to be extracted (Hinton et al., 2014). Items with factor loadings lower than .45 or cross-loadings across factors that exceeded .30 were deleted (Hinton et al., 2014; Pett et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2021). Twenty items were retained in the final version of the scale.

The authors then discussed the proper labelling of the factors based on the conceptual frameworks proposed by Metheny et al. (2008) and Wong et al. (2020). The five factors identified were labelled as positive expectations (Factor 1), motivational support (Factor 2), informational support (Factor 3), accessibility (Factor 4), and positive regard (Factor 5).

The internal consistency of the scale was determined using Cronbach’s alpha (α) (Cronbach, 1951) with the following criteria: .60 ≤ α < .80 was considered adequate, .80 ≤ α < .85 was good, and α ≥ .85 was excellent (Haertel, 2006). Cronbach’s alpha for the entire scale was .91 and the values for all individual subscales ranged from .757 to .840 (Table 1). This suggested that the items had adequate to good reliability.

Study 2: confirmatory factor analysis

Method

Participants

In Study 2, 384 students in Secondary 4, 5, or 6 (Grades 10, 11, or 12) from another two secondary schools completed the revised 20-item CRTSS-HKSS. These two schools were recruited in the same manner as for Study 1. The participants also reported their age, gender, and perceived academic ability. The students were native Chinese and aged 14 to 20 (mean age: 15.60 years; SD = .85). The sample contained slightly more female than male students (54.7%).

Measures

CRTS was investigated using the refined 20-item Chinese version of the CRTSS-HKSS. This revised scale covered five types of support and required students to record the frequency of each type of support on a 5-point Likert-type scale, from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Typical items include ‘My teachers think I should continue my education after secondary school’ and ‘My teachers are easy to talk to out of lesson time’.

Career development self-efficacy was measured using a 9-item subscale from the Career Development Self-Efficacy Inventory (Yuen et al., 2003, 2005). The scale was used to explore students’ confidence in conducting career exploration and planning. Typical items include ‘I am confident that I can strike a balance between interest and future prospects’ and ‘I am confident that I can explore different careers within areas of my interest’.

The inventory uses a 6-point Likert-type response scale from 1 (extremely lacking in confidence) to 6 (extremely confident). The factor structure of this subscale was evaluated in this sample of students (n = 384) using confirmatory factor analysis (CFI = .979, TLI = .969, RMSEA = .074). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .943. These results indicate an acceptable model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Hopelessness was assessed with one item: ‘The future looks dark to me’ (Aish & Wasserman, 2001; Beck et al., 1974). In previous research, when this item was applied to measure hopelessness for clinical use in Hong Kong, it was found to be statistically significant in detecting suicidal ideation (Yip & Cheung, 2006).

In Studies 1 and 2, paper-based questionnaires were completed by the students within 20 min during normal class time and then collected immediately. Teachers supervised the process but did not intervene or assist the students. Questionnaires that were incomplete or had the same response for all questions were screened out. Only data from completed questionnaires with valid responses were included in the analysis.

Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp, 2019) and AMOS 26.0 (Arbuckle, 2019). Missing data were treated using the maximum likelihood method before factor analyses were conducted (Schlomer et al., 2010). Exploratory factor analysis of the data from Study 1 was performed to identify the factor structure of the CRTSS-HKSS.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the data from Study 2 was then performed and the following models were compared to identify the best model fit: (a) a five-factor correlational model in which the five factors were allowed to be associated with each other, (b) a hierarchical model with a general factor and five second-order latent variables, and (c) a one-factor model. It was anticipated that the five-factor structure discovered in Study 1 would demonstrate a good model fit with the correlational model.

The scale’s validity was determined with a new sample of students by testing measurement invariance across genders and by observing the relationships of performance on the scale with demographic variables, career development self-efficacy, and hopelessness. Social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 2000) suggests that the availability of social support will enhance career development self-efficacy and lessen the damaging effects of negative psychological states. With this in mind, it was anticipated that CRTS would be positively correlated with career development self-efficacy and negatively correlated with hopelessness.

Results

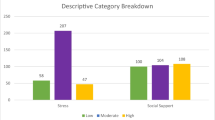

The five-factor CRTSS-HKSS was replicated and its structure tested. The scale showed excellent overall reliability (α = .938) (Haertel, 2006). The five factors of the CRTSS-HKSS showed adequate to good reliability (.759 ≤ α < .863). Descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s alpha values for the five factors are presented in Table 1.

Among the five factors, only Positive Expectations had an average score higher than 4. This implied that the students believed that they did receive support of this nature reasonably frequently in their school environment. The scores for the other four factors were between 3.24 and 3.66.

To identify the best-fitting factor structure, three competing models were compared. The fit indices and cut-off values used to assess the model fit were as follows: (a) CFI and TLI ≥ .90, (b) RMSEA ≤ .08, and (c) standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) ≤ .08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Marsh et al., 2004). As indicated in Table 2, the correlational model was retained as the best-fitting model because it produced the most promising results in matching the cut-off values of the fit indices. The results were as follows: CFI = .928, TLI = .914, RMSEA = .071, SRMR = .048, indicating that the cut-off values were met and the fit was adequate.

Correlations across the five identified factors were all significant, ranging from .57 to .84 (Figure 1). The factor loadings of all scale items were all significant, ranging from .614 to .854. Specifically, the factor loadings were as follows: Positive Expectations (.664 to .817), Motivational Support (.614 to .854), Informational Support (.731 to .831), Accessibility (.764 to .815), and Positive Regard (.642 to .795).

Gender invariance

To check for measurement invariance, the stepwise procedure suggested by Rudnev et al. (2018) was followed. Invariance is evident if ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA between the invariance models are less than .005 and .01, respectively (Chen, 2007). As illustrated in Table 3, ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA were both at acceptable levels for configural, metric, and scalar invariance tests, providing evidence that the CRTSS-HKSS can yield meaningful and comparable results for both male and female students.

Validity

Content and face validity were assured because the items in the CRTSS-HKSS were based on information gleaned from the relevant literature, plus direct input from students. The items had also undergone appraisal by relevant experts and been trialled with an age-appropriate group (Gay & Airasian, 2000).

Convergent validity is established when the variables being measured strongly correlate with other related variables within the given psychological construct (Thorndike, 1997). As shown in Table 1, the strength of the correlations between the five subscales of the CRTSS-HKSS was moderate to high (.468 ≤ r ≤ .698, p < .01). The correlation between the career development self-efficacy and hopelessness subscales was also significant. Career development self-efficacy was positively correlated with the five subscales of the CRTSS-HKSS, and the subscales were negatively correlated with hopelessness. Among the five subscales, Factor 3, Informational Support, showed the strongest positive correlation with career development self-efficacy (r = .539, p < .01), followed by Factor 5, Positive Regard (r = .516, p < .01). The negative correlation with hopelessness was the most significant with Factor 3, Informational Support (r = −.199), followed by Factor 4, Accessibility (r = −.158, p < .01). A negative relationship was observed between career development self-efficacy and hopelessness (−.415, p < .01).

General discussion

This study documents the development and validation of the CRTSS-HKSS based on data from two samples of senior secondary students (Grades 10–12) in Hong Kong. The results suggest that the CRTSS-HKSS is sound in terms of statistical fit, validity, and reliability. Measurement invariance across genders was confirmed. The instrument was developed based on focus group data and a review of the literature, suggesting that the CRTSS-HKSS is theoretically sound and is culturally adapted to the needs of Hong Kong students (Arthur & Collins, 2011). These are all essential qualities of a good instrument that directly addresses a specific group of adolescents (Lavik et al., 2018). As hypothesised, a positive relationship was found between CRTS as a form of social support and students’ career development self-efficacy. A negative relationship was found between CRTS and hopelessness, in which hopelessness operated as a negative psychological career barrier. The identification of these relationships enriches our understanding of the practical operation of CRTS in the real world.

The five factors identified within the CRTSS-HKSS resemble the nature of teacher support proposed by Lei et al. (2018). This new instrument examines a wider range of CRTS and highlights distinctive types of teacher support that were not previously included in existing instruments. Motivational support was included because it was positively and significantly correlated with career development self-efficacy (r = .472, p < .01). This result is consistent with previous empirical studies in which teacher support was found to be significantly correlated with students’ levels of motivation (Lazarides et al., 2018) and improved career decision-making and career exploration (Hirschi et al., 2011) as well as career development self-efficacy (Di Fabio & Kenny, 2015). Recent research has demonstrated significant positive relationships between motivational support, levels of self-efficacy, and occupational selection (Guay et al., 2020). Although Marciniak et al. (2021) recently attempted to include teachers’ motivational support when measuring career-related support in schools, the subscale they used did not address the types of motivational support essential to career development. It should be noted that among the various ways that teachers might support student motivation, only their support for ‘goal-setting’ was identified in the present study. The study has clarified that these students specifically need teachers’ advice to direct them towards their career goals. This also provides justification for the theoretical principles set out in the goal-setting theory of motivation in the school context (Locke & Latham, 2019).

Unlike other published instruments for exploring CRTS, this new scale examines informational support in more detail, recognising that career guidance in schools can only be effective when teachers have access to current information about the world of work and can explain this information clearly to their students (Alexander et al., 2019; OECD, 2004; Wong et al., 2020). The data collected for this study showed that Informational Support (Factor 3) had the most significant influence in enhancing the development of career self-efficacy (r = .539, p < .01). The literature has implied that students’ lack of confidence in developing a career path may be a psychological issue (see for example, Santilli et al., 2020), but the data in this study suggest that a lack of information may be the cause of the problem.

The new scale also examines students’ perceptions of the accessibility of school-based career guidance. Ease of access to such guidance allows students to approach teachers to clarify misunderstandings and receive advice (OECD, 2004). This is addressed in the new scale by items such as ‘If I want to talk about some issues connected with career planning, my teachers will be willing to listen’. The responses from the students clearly indicated that staff accessibility was significantly related to their career development self-efficacy and reduced hopelessness. Ease of access to teachers in schools could be used as a measure to assess the effectiveness of school-based career guidance.

Research has also shown that in addition to accessibility, supporting students at an emotional level is essential (Metheny et al., 2008). Consistent with previous research findings (Metheny et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2021), the data from this study in relation to the factor of Positive Regard suggest that ‘caring’ teacher behaviours could foster more positive career development.

Finally, at the present time, when the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted many students’ study plans, they are more susceptible to developing feelings of hopelessness concerning a future career path (Birtch et al., 2021; Ganson et al., 2020; OECD, 2020). Evidence obtained in this study suggests that the types of teacher support that most effectively help to reduce levels of hopelessness are providing accurate information and showing genuine care for students’ personal well-being. Teachers should also work with mental health professionals to provide emotional support to their students through individual and small group career counselling sessions (Blustein et al., 2020; Dieringer et al., 2017).

Limitations and directions for future research

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First is the problem always associated with ‘self-reporting’. It is possible that some students over- or underestimated their perceived levels of teacher support. Overestimation could be due to a student wishing to make his or her teachers ‘look good’ in a research study, for instance by ticking ‘always’ when the support was actually given only occasionally. Underestimation could occur when a student has not really recognised or appreciated the true amount of support being given. Second, the CRTSS-HKSS does not differentiate between students with one very supportive teacher and those who feel supported by most of their teachers. Further revision of the instrument could include a request that a respondent indicates for each item ‘Does this apply to all of your teachers or only to one teacher?’ Third, due to time constraints, the test–retest reliability of the CRTSS-HKSS was not established. This needs to be done because it is important to know whether respondents are likely to complete the items in the same way if asked to do so a few weeks later. Fourth, factor analyses on scale items designed to represent appraisal support (Tardy, 1985) and autonomy support (Deci & Ryan, 2000) were not statistically significant due to high cross-loadings. Further investigation is needed to understand the reason for this; it is possible that the wording of the items should be improved.

Conclusion

This article describes the development and validation of the CRTSS-HKSS, an instrument designed to assess Chinese adolescents’ perceptions of CRTS within the secondary school setting in Hong Kong. This represents an important contribution to the field of career guidance because the instrument is adapted to the local Chinese context (Arthur & Collins, 2011). Our findings suggest that the 20-item CRTSS-HKSS possesses good validity and reliability and is suitable for both male and female respondents.

In trialling and refining the instrument, it was found that the most valued forms of support were informational and motivational support, with ease of access and personal regard being appreciated by students in Hong Kong. Accessibility is a type of teacher support that has not been adequately addressed in previous reviews of the literature (Lei et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). A positive relationship was found between CRTS and students’ career development self-efficacy, and CRTS was also found to reduce feelings of hopelessness in regard to planning a career path. The findings of this study (and the immediate availability of the CRTSS-HKSS to teachers) should assist in clarifying the supportive role of teachers involved in career guidance in secondary schools everywhere.

References

Aish, A., & Wasserman, D. (2001). Does Beck’s Hopelessness Scale really measure several components? Psychological Medicine, 31(2), 367–372. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291701003300

Alexander, R., McCabe, G., & DeBacker, M. (2019). Careers and labour market information: An international review of the evidence. https://www.educationdevelopmenttrust.com/our-research-and-insights/research/careers-and-labour-market-information-an-internati

Arbuckle, J. L. (2019). Amos (Version 26.0) [Computer program]. SPSS.

Arthur, N., & Collins, S. (2011). Infusing culture in career counseling. Journal of Employment Counseling, 48(4), 147–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2011.tb01098.x

Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839x.00024

Beck, A., Weissman, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 861–865. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037562

Birtch, T. A., Chiang, F. F., Cai, Z., & Wang, J. (2021). Am I choosing the right career? The implications of COVID-19 on the occupational attitudes of hospitality management students. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95, 102931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102931

Blustein, D. L., Duffy, R., Ferreira, J. A., Cohen-Scali, V., Cinamon, R. G., & Allan, B. A. (2020). Unemployment in the time of COVID-19: A research agenda. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103436

Boysan, M. (2020). An integration of quadripartite and helplessness-hopelessness models of depression using the Turkish version of the Learned Helplessness Scale (LHS). British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 48(5), 650–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2019.1612033

Bray, M., & Koo, R. (2005). Education and society in Hong Kong and Macao: Comparative perspectives on continuity and change. Springer.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005

Burns, E. C. (2020). Factors that support high school completion: A longitudinal examination of quality teacher–student relationships and intentions to graduate. Journal of Adolescence, 84, 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.09.005

Census and Statistics Department. (2020). Women and men in Hong Kong: Key statistics. https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B11303032020AN20B0100.pdf

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Chong, W. H., Liem, G. A. D., Huan, V. S., Kit, P. L., & Ang, R. P. (2018). Student perceptions of self-efficacy and teacher support for learning in fostering youth competencies: Roles of affective and cognitive engagement. Journal of Adolescence, 68, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.07.002

Chow, S. L., Fu, K. W., & Ng, Y. L. (2020). Development of the Hong Kong identity scale: Differentiation between Hong Kong ‘Locals’ and Mainland Chinese in cultural and civic domains. Journal of Contemporary China, 29(124), 568–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2019.1677365

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

Datu, J. A. D., & Yang, W. (2019). Academic buoyancy, academic motivation, and academic achievement among Filipino high school students. Current Psychology, 40(8), 3958–3965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00358-y

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Di Fabio, A., & Kenny, M. (2012). Emotional intelligence and perceived social support among Italian high school students. Journal of Career Development, 39, 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845311421005

Di Fabio, A., & Kenny, M. E. (2015). The contributions of emotional intelligence and social support for adaptive career progress among Italian youth. Journal of Career Development, 42(1), 48–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845314533420

Dieringer, D. D., Lenz, J. G., Hayden, S. C. W., & Peterson, G. W. (2017). The relation of negative career thoughts to depression and hopelessness. The Career Development Quarterly, 65(2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12089

Federation of Youth Groups. (2019). Improving the effectiveness of career and life planning education. https://yrc.hkfyg.org.hk/en/2019/01/30/improving-the-effectiveness-of-career-and-life-planning-education-2/

Finnish Youth Barometer. (2017). Opin polut ja pientareet. Nuorisoparometri 2017. [Educational paths. Youth Barometer]. https://tietoanuorista.fi/nuorisobarometri/nuorisobarometri-2017/

Ganson, K. T., Tsai, A. C., Weiser, S. D., Benabou, S. E., & Nagata, J. M. (2020). Job insecurity and symptoms of anxiety and depression among U.S. young adults during COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(1), 53–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.10.008

Gati, I., & Kulcsár, V. (2021). Making better career decisions: From challenges to opportunities. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 126, 103545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103545

Gay, L. R., & Airasian, P. (2000). Educational research. Merrill.

Guay, F., Bureau, J. S., Litalien, D., Ratelle, C. F., & Bradet, R. (2020). A self-determination theory perspective on RIASEC occupational themes: Motivation types as predictors of self-efficacy and college program domain. Motivation Science, 6(2), 164–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000142

Gysbers, N. C. (2000). Implementing a whole school approach to guidance through a comprehensive guidance program. Asian Journal of Counselling, 7, 5–17.

Haertel, E. H. (2006). Reliability. In R. L. Brennan (Ed.), Educational measurement (pp. 65–110). American Council on Education and Praeger.

Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2010). Classroom environments and developmental processes. Conceptualization and measurement. In J. L. Meece & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Handbook of research on schools, schooling, and human development (pp. 25–41). Routledge.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Hinton, P. R., McMurray, I., & Brownlow, C. (2014). SPSS explained. Routledge.

Hirschi, A. (2012). The career resources model: An integrative framework for career counsellors. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 40, 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2012.700506

Hirschi, A. (2018). The fourth industrial revolution: Issues and implications for career research and practice. The Career Development Quarterly, 66, 192–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12142

Hirschi, A., Niles, S. G., & Akos, P. (2011). Engagement in adolescent career preparation: Social support, personality and the development of choice decidedness and congruence. Journal of Adolescence, 34(1), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.009

Ho, Y. F., & Leung, S. M. A. (2016). Career guidance in Hong Kong: From policy ideal to school practice. The Career Development Quarterly, 64(3), 216–230. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12056

Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02289447

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hui, T., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2018). Career adaptability, self-esteem, and social support among Hong Kong university students. The Career Development Quarterly, 66(2), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12118

IBM Corp. (2019). IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 26.0. IBM Corp.

Jimerson, S. R., & Haddock, A. D. (2015). Understanding the importance of teachers in facilitating student success: Contemporary science, practice, and policy. School Psychology Quarterly, 30(4), 488–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000134

Kenny, M., Blustein, D., Chaves, A., Grossman, J., & Gallagher, L. (2003). The role of perceived barriers and relational support in the educational and vocational lives of high school students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.2.142

Kingsbury, M., Clayborne, Z., Colman, I., & Kirkbride, J. B. (2020). The protective effect of neighbourhood social cohesion on adolescent mental health following stressful life events. Psychological Medicine, 50(8), 1292–1299. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291719001235

Lam, M. O. L. (1996). Conceptions of an ideal and creative pupil among primary school teachers, using different approaches (Master’s thesis). University of Hong Kong.

Lavik, K. O., Veseth, M., Frøysa, H., Binder, P. E., & Moltu, C. (2018). ‘Nobody else can lead your life’: What adolescents need from psychotherapists in change processes. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 18(3), 262–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12166

Lazarides, R., Buchholz, J., & Rubach, C. (2018). Teacher enthusiasm and self-efficacy, student-perceived mastery goal orientation, and student motivation in mathematics classrooms. Teaching and Teacher Education, 69, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.017

Lee, M., Wong, B., Chow, B., & McBride-Chang, C. (2006). Predictors of suicide ideation and depression in Hong Kong adolescents: Perceptions of academic and family climates. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 36, 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2006.36.1.82

Lei, H., Cui, Y., & Chiu, M. (2018). The relationship between teacher support and students’ academic emotions: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2288. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02288

Lent, R., Brown, S., & Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.36

Leung, M. K., Wong, E. K. P., & Pow, S. K. (2002). A study of the roles and duties of secondary 1 to 3 form teachers in Hong Kong secondary schools. http://www.hkta1934.org.hk/NewHorizon/abstract/2002n/page67.pdf

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2011). Expecting my child to become “dragon”—development of the Chinese Parental Expectation on Child’s Future Scale. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 10(3), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijdhd.2011.043

Leung, S., Chan, C., & Leahy, T. (2007). Counseling psychology in Hong Kong: A germinating discipline. Applied Psychology, 56, 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00275.x

Leung, S. A. (2002). Career counseling in Hong Kong: Meeting the social challenges. The Career Development Quarterly, 50(3), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2002.tb00899.x

Locke, E., & Latham, G. (2019). The development of goal setting theory: A half century retrospective. Motivation Science, 5(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000127

Lynass, R., Pykhtina, O., & Cooper, M. (2012). A thematic analysis of young people’s experience of counselling in five secondary schools in the UK. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 12, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2011.580853

Marciniak, J., Hirschi, A., Johnston, C. S., & Haenggli, M. (2021). Measuring career preparedness among adolescents: Development and validation of the career resources questionnaire—adolescent version. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(1), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072720943838

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling, 11(3), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

Metheny, J., McWhirter, E. H., & O’Neil, M. E. (2008). Measuring perceived teacher support and its influence on adolescent career development. Journal of Career Assessment, 16(2), 218–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707313198

Michaeli, Y., Dickson, D. J., & Shulman, S. (2018). Parental and nonparental career-related support among young adults: Antecedents and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Career Development, 45(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845316671428

Moody’s Analytics. (2020). Hong Kong: Unemployment rate. https://www.economy.com/hong-kong/unemployment-rate

Morisano, D., Hirsh, J., Peterson, J., Pihl, R., & Shore, B. (2010). Setting, elaborating, and reflecting on personal goals improves academic performance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018478

Moyer, A., & Goldberg, A. (2020). Foster youth’s educational challenges and supports: Perspectives of teachers, foster parents, and former foster youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 37, 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-019-00640-9

OECD. (2004). Career guidance and public policy: Bridging the gap. http://www.oecd.org/edu/innovation-education/34050171.pdf

OECD. (2020). Career ready? How schools can better prepare young people for working life in the era of COVID-19. https://www.oecd.org/education/dream-jobs-teenagers-career-aspirations-and-the-future-of-work.htm

Parvazian, S., Gill, J., & Chiera, B. (2017). Higher education, women, and sociocultural change: A closer look at the statistics. SAGE Open, 7(2), 2158244017700230. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017700230

Perry, J., Liu, X., & Pabian, Y. (2010). School engagement as a mediator of academic performance among urban youth: The role of career preparation, parental career support, and teacher support. Counseling Psychologist, 38, 269–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000009349272

Pett, M. A., Lackey, N. R., & Sullivan, J. J. (2003). Making sense of factor analysis: The use of factor analysis for instrument development in health care research. Sage.

Phillips, S. D., Blustein, D. L., Jobin-Davis, K., & White, S. F. (2002). Preparation for the school-to-work transition: The views of high school students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(2), 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1853

Postiglione, G. A., & Leung, J. Y. M. (1991). Education and society in Hong Kong: Toward one country and two systems. Routledge.

Reise, S., Waller, N., & Comrey, A. (2000). Factor analysis and scale revision. Psychological Assessment, 12, 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.12.3.287

Rudnev, M., Lytkina, E., Davidov, E., Schmidt, P., & Zick, A. (2018). Testing measurement invariance for a second-order factor: A cross-national test of the alienation scale. Methods, Data, Analyses: A Journal for Quantitative Methods and Survey Methodology, 12(1), 47–76. https://doi.org/10.12758/mda.2017.11

Ryan, J., & Louie, K. (2013). False dichotomy? ‘Western’ and ‘Confucian’ concepts of scholarship and learning. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 39(4), 404–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00347.x

Salili, F., Chiu, C. Y., & Hong, Y. Y. (2001). Student motivation: The culture and context of learning. Plenum Press.

Samuel, R., & Burger, K. (2020). Negative life events, self-efficacy, and social support: Risk and protective factors for school dropout intentions and dropout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(5), 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000406

Santilli, S., di Maggio, I., Ginevra, M. C., Nota, L., & Soresi, S. (2020). ‘Looking to the future and the university in an inclusive and sustainable way’: A career intervention for high school students. Sustainability, 12(21), 9048. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219048

Schlomer, G. L., Bauman, S., & Card, N. A. (2010). Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018082

Schwarzer, C., & Buchwald, P. (2004). Social support. In C. Spielberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of applied psychology (pp. 435–441). Academic Press.

Shek, D. T. L., & Wu, F. K. Y. (2016). Positive youth development and academic behavior in Chinese secondary school students in Hong Kong. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 15(4), 455–459. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijdhd-2017-5012

Stebleton, M. J., & Kaler, L. S. (2020). Preparing college students for the end of work: The role of meaning. Journal of College and Character, 21(2), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2020.1741396

Suldo, S. M., Friedrich, A. A., White, T., Farmer, J., Minch, D., & Michalowski, J. (2009). Teacher support and adolescents’ subjective well-being: A mixed-methods investigation. School Psychology Review, 38(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2009.12087850

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidel, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. Allyn & Bacon.

Tardy, C. H. (1985). Social support measurement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 13(2), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00905728

Thorndike, R. M. (1997). Measurement and evaluation in psychology and education. Merrill.

Tsang, K. K. (2018). Teacher alienation in Hong Kong. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 39(3), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2016.1261084

Tsang, K. K., Lian, Y., & Zhu, Z. (2021). Alienated learning in Hong Kong: A Marxist perspective. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53(2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1767588

Tsui, K. T., Lee, C. K. J., Hui, K. F. S., Chun, W. S. D., & Chan, N. C. K. (2019). Academic and career aspiration and destinations: A Hong Kong perspective on adolescent transition. Education Research International, 2019, 3421953. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3421953

Ulas, O., & Yildirim, İ. (2019). Influence of locus of control, perceived career barriers, negative affect, and hopelessness on career decision-making self-efficacy among Turkish university students. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 19(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-018-9370-9

Wang, X. (2013). Why students choose STEM majors: Motivation, high school learning, and postsecondary context of support. American Educational Research Journal, 50, 1081–1121. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831213488622

Watts, A. G. (2013). Career guidance and orientation. https://unevoc.unesco.org/fileadmin/up/2013_epub_revisiting_global_trends_in_tvet_chapter7.pdf

Williams, W. D. F. (1973). Careers information, guidance and counselling in Hong Kong: Research project, January–May 1973. Kwun Tong Vocational Training Centre.

Wong, L. P. W. (2017). Career and life planning education in Hong Kong: Challenges and opportunities on the theoretical and empirical fronts. Hong Kong Teachers’ Centre Journal, 16, 125–149. https://www.edb.org.hk/HKTC/download/journal/j16/C01.pdf

Wong, L. P. W. (2018). School counselor’s reflections on career and life planning education in Hong Kong: How career theories can be used to inform practice. Journal of Counseling Profession, 1(1), 1–33.

Wong, L. P. W., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2019). Technology-infused career and life planning education. Asia Pacific Career Development Journal, 2(2), 51–62.

Wong, L. P. W., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2021). Career guidance and counseling: The nature and types of career-related teacher social support in Hong Kong secondary schools. Unpublished manuscript.

Wong, L. P. W., & Yuen, M. T. (2019). Career guidance and counseling in secondary schools in Hong Kong: A historical overview. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 9, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.18401/2019.9.1.1

Wong, L. P. W., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2020). Career-related teacher support: A review of roles that teachers play in supporting students’ career planning. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 1(1), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2020.30

World Bank Group Jobs. (2020). Managing the employment impacts of the COVID-19 crisis: Policy options for relief and restructuring. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/34263

Yang, L., & Wong, L. P. W. (2020). Career and life planning education: Extending the self-concept theory and its multidimensional model to assess career-related self-concept of students with diverse abilities. ECNU Review of Education, 3(4), 659–677. https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531120930956

Yip, P. S. F., & Cheung, Y. B. (2006). Quick assessment of hopelessness: A cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 4(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-13

Yuen, C. Y. M., Cheung, A. C. K., Leung, S., & Tang, H. (2020). Transition from secondary to post-secondary education: Access, obstacles, and success factors of immigrant, minority and low-income youth in Hong Kong. https://www.eduhk.hk/zht/major-projects/transition-from-secondary-to-post-secondary-education-access-obstacles-and-success-factors-of-immigrant-minority-and-low-income-youth-in-hong-kong

Yuen, M., Lau, P. S. Y., Leung, T. K. M., Shea, P. M. K., Chan, R. M. C., Hui, E. K. P., & Gysbers, N. C. (2003). Life skills development and comprehensive guidance program: Theories and practices. Life Skills Development Project, Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong. http://web.hku.hk/~life/pdf/rp/Yuen%20Life%20Skills%20Development%20Theories%20and%20Practices.pdf

Yuen, M., Gysbers, N. C., Chan, R. M. C., Lau, P. S. Y., Leung, T. K. M., Hui, E. K. P., & Shea, P. M. K. (2005). Developing a career development self-efficacy instrument for Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 5(1), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-005-2126-3

Zee, M., Koomen, H. M. Y., & Van der Veen, I. (2013). Student–teacher relationship quality and academic adjustment in upper elementary school: The role of student personality. Journal of School Psychology, 51(4), 517–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2013.05.003

Zhang, J., Chen, G., & Yuen, M. (2021). Development and validation of the Career-related Teacher Support Scale: Data from China. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 21(1), 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-020-09435-2

Zhang, J., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2018). Teacher support for career development: An integrative review and research agenda. Career Development International, 23(2), 122–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-09-2016-0155

Zhang, J., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2020). Supporting the career development of technical education students in China: The roles played by teachers. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20, 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-019-09398-z

Acknowledgements

The article is based on the first author’s doctoral research under the supervision of the second and third authors at the Faculty of Education, University of Hong Kong.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, L.P.W., Chen, G. & Yuen, M. Investigating career-related teacher support for Chinese secondary school students in Hong Kong. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance 23, 719–740 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09525-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09525-3