Abstract

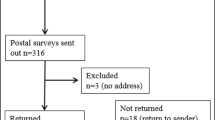

Introduction Interest in searching for mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 is high. Knowledge regarding these genes and the advantages and limitations of genetic testing is limited. It is unknown whether increasing knowledge about breast cancer genetic testing alters interest in testing. Methods Three hundred and seventy nine women (260 with a family history of breast cancer; 119 with breast cancer) from The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust were randomised to receive or not receive written educational information on cancer genetics. A questionnaire was completed assessing interest in BRCA1 testing and knowledge on breast cancer genetics and screening. Actual uptake of BRCA1 testing is reported with a six year follow-up. Results Eighty nine percent of women at risk of breast cancer and 76% of women with breast cancer were interested in BRCA1 testing (P < 0.0001). Provision of educational information did not affect level of interest. Knowledge about breast cancer susceptibility genes was poor. According to the NICE guidelines regarding eligibility for BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing, the families of 66% of the at risk group and 13% of the women with breast cancer would be eligible for testing (probability of BRCA1 mutation ≥20%). Within six years of randomisation, genetic testing was actually undertaken on 12 women, only 10 of whom would now be eligible, on the NICE guidelines. Conclusions There is strong interest in BRCA1 testing. Despite considerable ignorance of factors affecting the inheritance of breast cancer, education neither reduced nor increased interest to undergo testing. The NICE guidelines successfully triage those with a high breast cancer risk to be managed in cancer genetics clinics.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Eeles RA (1999) Screening for hereditary cancer and genetic testing, epitomised by breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 35:1954–1962. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00246-4

Lerman C, Lustbader E, Rimer B et al (1995) Effects of individualized breast cancer risk counseling: a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 87:286–292. doi:10.1093/jnci/87.4.286

Bluman LG, Rimer BK, Berry DA et al (1999) Attitudes, knowledge, and risk perceptions of women with breast and/or ovarian cancer considering testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2. J Clin Oncol 17:1040–1046

Lerman C, Seay J, Balshem A et al (1995) Interest in genetic testing among first-degree relatives of breast cancer patients. Am J Med Genet 57:385–392. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320570304

Struewing JP, Lerman C, Kase RG et al (1995) Anticipated uptake and impact of genetic testing in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 4:169–173

Tambor ES, Rimer BK, Strigo TS (1997) Genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: awareness and interest among women in the general population. Am J Med Genet 68:43–49. doi :10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19970110)68:1<43::AID-AJMG8>3.0.CO;2-Z

Lerman C, Daly M, Masny A et al (1994) Attitudes about genetic testing for breast-ovarian cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol 12:843–850

Press NA, Yasui Y, Reynolds S et al (2001) Women’s interest in genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility may be based on unrealistic expectations. Am J Med Genet 99:99–110. doi :10.1002/1096-8628(2000)9999:999<00::AID-AJMG1142>3.0.CO;2-I

Julian-Reynier C, Sobol H, Sevilla C et al. The French Cancer Genetic Network (2000) Uptake of hereditary breast/ovarian cancer genetic testing in a French national sample of BRCA1 families. Psychooncology 9:504–510. doi :10.1002/1099-1611(200011/12)9:6<504::AID-PON491>3.0.CO;2-R

Meijers-Heijboer EJ, Verhoog LC, Brekelmans CTM et al (2000) Presymptomatic DNA testing and prophylactic surgery in families with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Lancet 355:2015–2020. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02347-3

McInerney-Leo A, Biesecker BB, Hadley DW et al (2004) BRCA1/2 testing in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families: effectiveness of problem-solving training as a counseling intervention. Am J Med Genet 130A:221–227. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.30265

Brooks L, Lennard F, Shenton A et al (2004) BRCA1/2 predictive testing: a study of uptake in two centres. Eur J Hum Genet 12:654–662. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201206

Meijers-Heijboer H, Brekelmans CTM, Menke-Pluymers M et al (2003) Use of genetic testing and prophylactic mastectomy and oophorectomy in women with breast or ovarian cancer from families with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol 21:1675–1681. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.09.052

Velicer CM, Taplin S (2001) Genetic testing for breast cancer: where are health care providers in the decision process. Genet Med 3:112–119. doi:10.1097/00125817-200103000-00005

Schwartz MD, Benkendorf J, Lerman C et al (2001) Impact of educational print materials on knowledge, attitudes, and interest in BRCA1/BRCA2: testing among Ashkenazi Jewish women. Cancer 92:932–940. doi :10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4<932::AID-CNCR1403>3.0.CO;2-Q

Brain K, Norman P, Gray J et al (2002) A randomized trial of specialist genetic assessment: psychological impact on women at different levels of familial breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer 86:233–238. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600051

Green MJ, Peterson SK, Wagner Baker M et al (2004) Effect of a computer-based decision aid on knowledge, perceptions, and intentions about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 292:442–452. doi:10.1001/jama.292.4.442

Lloyd S, Watson M, Waites B et al (1996) Familial breast cancer: a controlled study of risk perception, psychological morbidity and health beliefs in women attending for genetic counselling. Br J Cancer 74:482–487

Gurmankin AD, Domchek S, Stopfer J et al (2005) Patients’ resistance to risk information in genetic counseling for BRCA1/2. Arch Intern Med 165:523–529. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.5.523

Braithwaite D, Emery J, Walter F et al (2004) Psychological impact of genetic counseling for familial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 96:122–133

Meiser B, Butow P, Schnieden V et al (2000) Psychological adjustment of women at increased risk of developing hereditary breast cancer. Psychol Health Med 5:377–388. doi:10.1080/713690217

Meiser B, Halliday J (2002) What is the impact of genetic counseling in women at risk of developing hereditary breast cancer? A meta-analytic review. Soc Sci Med 54:1463–1470. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00133-2

Sivell S, Iredale R, Gray J et al (2007) Cancer genetic risk assessment for individuals at risk of familial breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 18:CD003721

Bish A, Sutton S, Jacobs C et al (2002) Changes in psychological distress after cancer genetic counseling: a comparison of affected and unaffected women. Br J Cancer 86:43–50. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600030

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2006) Familial breast cancer: the classification and care of women at risk of familial breast cancer in primary, secondary and tertiary care (partial update of CG14). Clinical Guideline 41:4–33. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG41. Accessed January 2008

Randall J, Butow P, Kirk J et al (2001) Psychological impact of genetic counselling and testing in women with breast cancer. Intern Med J 31:397–405. doi:10.1046/j.1445-5994.2001.00091.x

Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M and the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium (1998) Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet 62:676–689. doi:10.1086/301749

Lerman C, Biesecker B, Benkendorf JL et al (1997) Controlled trial of pretest education approaches to enhance informed decision-making for BRCA1 gene testing. J Natl Cancer Inst 89:148–157. doi:10.1093/jnci/89.2.148

Appleton S, Watson M, Rush R et al (2004) A randomised controlled trial of a psychoeducational intervention for women at increased risk of breast cancer. Br J Cancer 90:41–47. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601519

Skinner CS, Schildkraut JM, Berry D et al (2002) Pre-counseling education materials for BRCA testing: does tailoring make a difference? Genet Test 6:93–105. doi:10.1089/10906570260199348

Wang C, Gonzalez R, Milliron KJ et al (2005) Genetic counseling for BRCA1/2: a randomized controlled trial of two strategies to facilitate the education and counseling process. Am J Med Genet 134A:66–73. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.30577

Bowen DJ, Burke W, Yasui Y et al (2002) Effects of risk counseling on interest in breast cancer genetic testing for lower risk women. Genet Med 4:359–365. doi:10.1097/00125817-200209000-00007

Mancini J, Nogues C, Adenis C et al (2006) Impact of an information booklet on satisfaction and decision-making about BRCA genetic testing. Eur J Cancer 42:871–881. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2005.10.029

American Society of Clinical Oncology (2003) American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol 21:2397–2406. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.03.189

Acknowledgements

The Corinne Burton Trust and Dr Eeles’ research fund provided funding for the study. We also acknowledge funding from The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust. Sue Gray is a Corinne Burton Trust nurse. We should like to thank Professor John Yarnold for entering patients into this study. We should like to thank the Clinical Trials Unit (Professor J Bliss and colleagues) at the Institute of Cancer Research for performing the randomisation. Funding The funding bodies played no part in study design, analysis or report writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Those randomised to receive written educational information in this study received the following:

You may have heard about a gene called BRCA1 that is carried by a small number (approximately 2–3%) of women who have breast cancer. The chance of having had breast cancer as a result of the inheritance of an alteration in this gene is therefore quite low, but it is higher if the breast cancer has occurred at a younger age. Usually these women have a family history of the disease; however, not all families with breast cancer have this gene. It is believed that this gene may be passed from one generation to the next in these affected families. In these families, some family members will inherit the gene and others will not. Both men and women have an equal chance of inheriting and passing on this gene.

A woman who has the gene has a high risk of developing breast cancer (80–90%) during her lifetime. Women who carry the BRCA1 gene, with family histories of breast and ovarian cancers, have an increased risk for developing both cancers. A person with the BRCA1 gene has a 50% chance of passing this gene on to each child. A woman who is not a gene carrier but is in one of these families where BRCA1 is present has the same risk of developing breast cancer as a woman with no family history of breast cancer. She should therefore, have the screening offered to the rest of the population. Women who carry the gene can be offered several options. All of these are not yet proven to reduce cancer risk. These are: early screening by mammography (for breast cancer) and ultrasound (for ovarian cancer), drug prevention using Tamoxifen or removal of breast and/or ovarian tissue.

It will shortly become possible to offer the BRCA1 breast cancer gene test to a small number of people in very high risk families; however, it is not possible at this time to test numerous individuals to see if they are carrying the gene (BRCA1) for breast cancer. However, in the near future (over the next 2 years), a blood test to determine which family members have this gene will become more widely available.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hall, J., Gray, S., A’Hern, R. et al. Genetic testing for BRCA1: effects of a randomised study of knowledge provision on interest in testing and long term test uptake; implications for the NICE guidelines. Familial Cancer 8, 5–13 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-008-9201-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-008-9201-0