Abstract

Mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek) is an important pulse crop in India. A major constraint for improved productivity is the yield loss caused by mungbean yellow mosaic disease (MYMD). This disease is caused by several begomoviruses which are transmitted by the whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). The objective of this study was to identify the predominant begomoviruses infecting mungbean and the major cryptic species of B. tabaci associated with this crop in India. The indigenous B. tabaci cryptic species Asia II 1 was found dominant in Northern India, whereas Asia II 8 was found predominant in Southern India. Repeated samplings over consecutive years indicate a stable situation with, Mungbean yellow mosaic virus strains genetically most similar to a strain from urdbean (MYMV-Urdbean) predominant in North India, strains most similar to MYMV-Vigna predominant in South India, and Mungbean yellow mosaic India virus (MYMIV) strains predominant in Eastern India. In field studies, mungbean line NM 94 showed a high level of tolerance to the disease in the Eastern state of Odisha where MYMIV was predominant and in the Southern state of Andhra Pradesh where MYMV-Vigna was predominant, but only a moderate level of tolerance in the Southern state of Tamil Nadu. However, in Northern parts of India where there was high inoculum pressure of MYMV-Urdbean during the Kharif season, NM 94 developed severe yellow mosaic symptoms. The identification of high level of tolerance in mungbean lines such as ML 1628 and of resistance in black gram and rice bean provides hope for tackling the disease through resistance breeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek) is the third most important pulse crop in India after chickpea and pigeonpea, accounting for 3.4 million ha or 15% of the total legume area sown (Nair et al. 2012). One of the major constraints for improved productivity of mungbean is the damage caused by yellow mosaic disease which is caused by different strains of at least two different species of the genus Begomovirus: Mungbean yellow mosaic virus (MYMV) and Mungbean yellow mosaic India virus (MYMIV) (Tsai et al. 2013). Both are members of the evolutionarily distinct subgroup of the bipartite begomoviruses (genomes composed of circular single-stranded DNA-A and DNA-B components of approx. 2.7 kb) known as ‘Legumoviruses’ (Ilyas et al. 2009). Eight different bipartite begomovirus species are known to cause yellow mosaic disease in more than 10 legume species (Akram et al. 2015). Begomoviruses are transmitted by the whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera, Aleyrodidae) in a persistent circulative manner (Markham et al. 1994). Based on mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (mtCOI) partial sequences, B. tabaci is a complex composed of at least 34 cryptic species (Boykin and De Barro 2014), hereafter referred to as species. Although these species are morphologically indistinguishable, they show considerable variation in their biological traits. For example, the invasive nature of the Middle East-Asia Minor 1 (MEAM1) and Mediterranean (MED) species has been associated with their greater fecundity and relative polyphagy, and propensity for developing resistance to many of the insecticides used for their control (Horowitz et al. 2007). An invasion of these species often goes along with severe virus outbreaks (Pan et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2014; Guo et al. 2015; Ning et al. 2015) as both transmit begomoviruses very efficiently. Therefore, a comprehensive knowledge on the identity and distribution of B. tabaci species is an important prerequisite for development of efficient and sustainable pest control measures to reduce begomovirus infection.

The most sustainable method and the one to be adopted with ease by the farmers to manage begomoviruses and the yield losses caused in mungbean production is to deploy cultivars exhibiting resistance or tolerance to the viruses. Tolerance or resistance to a virus that was assumed to be MYMV was reported as conferred by a single recessive gene (Singh and Patel 1977; Malik et al. 1988), complementary recessive genes (Shukla and Pandya 1985; Alam et al. 2014), and a dominant gene and complementary recessive genes (Sandhu et al. 1985). A RFLP study also indicated a single recessive gene (reviewed by Poehlman 1991). However, Dhole and Reddy (2012) reported that two recessive genes are responsible for MYMV resistance. Resistance to MYMV was identified in V. radiata var. sublobata Roxb. Verde., a progenitor of mungbean, and genes for resistance have been transferred to commercial mungbean cultivars (Singh and Ahuja 1977). RAPD, SCAR and ISSR markers for MYMV resistance have been reported, but not successfully used in breeding, probably due to poor reproducibility and low degree of linkage (Selvi et al. 2006; Somta et al. 2009; Souframanien and Gopalakrishna 2006). Two resistance markers for MYMIV were identified based on conserved R-gene sequences, and successfully applied for germplasm screening (Maiti et al. 2011). A field screening in Pakistan identified three out of 146 recombinant in-bred lines (RILs) developed in Thailand as tolerant since they displayed milder disease symptoms despite high disease pressure (Akhtar et al. 2009). Dhole and Reddy (2013) developed a SCAR marker located near the MYMV resistance gene. One reason for the difficulty in obtaining durable resistance to begomoviruses – even after 40 years of resistance breeding efforts in mungbean and the release of resistant/tolerant lines – may be that most resistance screening has been performed in the field, with little account being taken of the different begomovirus species/strains able to cause the disease. Thus, although early screening and breeding work in India may have been against a strain of MYMV, by the time of the variety release, a new strain/species of begomovirus with different virulence (e.g. MYMIV) may have replaced the original strains in some areas. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to identify the predominant whitefly and begomovirus species associated with mungbean in India, and to evaluate mungbean lines for resistance in the field at different locations under natural MYMD infection pressure.

Materials and methods

Analysis of Bemisia tabaci cryptic species

Whiteflies were collected mainly from legume crops during surveys in mungbean growing regions of India from 2012 to 2014. Whitefly specimen were preserved in 95% ethanol and shipped to the DSMZ Plant Virus Department (Braunschweig, Germany) for further analyses. A summary of geographical locations, host plants and dates of collection is provided in Table 1.

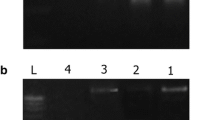

Total genomic DNA was extracted from individual female whiteflies by homogenizing in 200 μl lysis buffer (InviMag Plant DNA Mini Kit, Stratec Molecular GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and 10 μl proteinase K (10 mg ml−1). Further steps were performed following the manufacturers´ instructions but using half of the recommended volume of each solution. Part of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I (mtCOI) gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the universal primers C1-J-2195 and L2-N-3014 (Frohlich et al. 1999) and 2 μl template DNA in 25 μl reaction volume. PCR products were analyzed on agarose gels and at least one PCR amplicon per sampling location was sequenced (Sequiserve, Vaterstetten, Germany). Partial mtCOI sequences were trimmed to 657 bp (Dinsdale et al. 2010) and analyzed using the Global Bemisia dataset release version 31 (De Barro and Boykin 2013; Boykin and De Barro 2014) for species identification. Sequences were aligned using ClustalW v1.8 (Thompson et al. 1994). A phylogenetic tree was inferred using MrBayes ver. 3.2; (Ronquist et al. 2012) following the method described by Dinsdale et al. (2010). Sequences of this study were assigned to species (Dinsdale et al. 2010) and named according to Boykin and De Barro (2014) with modifications. The format is: Species_Country [In = India]_Year of sampling_Location_Host. A total of 23 sequences were submitted to GenBank (Accession numbers KR020523- KR020545).

Detection of begomoviruses

Leaf samples were collected from mungbean and other legume plants and weeds showing virus-like symptoms from mungbean growing regions in India during 2012–2014. Analyses of the air-dried samples were undertaken at the DSMZ Plant Virus Department. DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturers´ instructions and amplified with specific and universal primers as described by Naimuddin et al. (2011) and Briddon et al. (2002). DNA of individual female whiteflies was included in the analysis. If PCR was negative with specific primers for MYMV and MYMIV, universal primers for legumovirus DNA-A (LegA-cpF1, LegA-cpR2, Dr. Ha Viet Cuong, pers. communication) were used. PCR products were sequenced (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany). Sequence analysis was done using NCBI/Blast and alignments were performed with ClustalW (Thompson et al. 1994). Full-length clones were prepared from selected samples using abutting primers (Briddon et al. 1993), sequenced and analyzed as described before. A summary of geographical locations, host plants and dates of collection is provided in Table 2.

Screening of mungbean lines (Vigna radiata) for resistance or tolerance to yellow mosaic in the field

In 2012, 50 mungbean lines (Table 3) were screened against yellow mosaic disease at three sites; Tirunelveli (Tamil Nadu), Punjab Agricultural University (PAU) Ludhiana (Punjab) and Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), Pusa (New Delhi). In Tamil Nadu the sowing was in March, while in Punjab and New Delhi sowings were during July (Kharif season). The trials were set out in a randomized block design with three replicates. Each line was sown in a single row 4 m long with spacings of 40 and 10 cm between rows and plants respectively. KPS 2 was planted as a susceptible control in every third row. Yellow mosaic disease symptoms were assessed macroscopically after 55 days of sowing. All plants in a row were scored (Table 4) using the rating scale of 1 (no symptoms) to 6 (very severe symptoms). Average seed yield per plant was recorded after harvest for each line at the Tirunelveli site. During 2013 spring season (March sown crop) the trial was repeated at PAU, Ludhiana, Punjab.

In the 2013 Kharif season (July planting), 40 mungbean lines, one black gram (Vigna mungo) and one rice bean (Vigna umbellata) were screened (Table 5) at Punjab Agricultural University (PAU) Ludhiana (Punjab) and at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), Pusa (New Delhi) in an alpha lattice design of (seven blocks × six entries) in three replicates. RMG 353 and KPS 2 were planted as susceptible controls in every third row in Ludhiana and New Delhi respectively.

In 2014, 40 mungbean lines (Table 6) were screened at Orissa University of Agriculture and Technology (OUAT) campus, Bhubneshwar, Odisha. A row column design with three replications was followed. The trial was sown in April. Each line was sown in a single row 4 m long with spacing of 40 and 10 cm between rows and plants respectively. KPS 2 was planted as a susceptible control in every third row. Symptoms were assessed after 55 days of sowing as described before. A screening trial was sown in a farmer’s field in Srikakulam, Eastern Andhra Pradesh in December 2014 (Table 6). A row-column design with three replications was followed. Each line was sown in a single row of 2 m length with a spacing of 60 and 15 cm between rows and plants respectively. Assessment of disease symptoms was done using the 1–6 rating scale described above.

Data analysis of field experiments

For yellow mosaic response and seed yield per plant, year wise (2012 and 2013) combined analysis of variance across the sites were performed to test the significance of site (S), line (L) and site X line (SL) using SAS MIXED procedure (SAS V9.3). Individual site residual variances were modelled into combined analysis and least square means were estimated for main and interaction effects. All score data were subjected to square root transformation for normalising the data. A site regression model (SREG, commonly known as GGE Biplot) was used to visualize SL pattern to understand interrelationships among various test sites and line evaluation (Yan and Tinker 2006).

The site regression model was:

Where Yij. is the mean yellow mosaic response score of ith line in jth site, μ is the overall mean, δi is the line effect, βj is the site effect, λk is the singular value for IPCA axis k: δik is the line eigenvector value for IPCA axis n, βjk is the site eigenvector value for IPCA axis k and εij. is the residual error assumed to be normally and independently distributed (0, σ2/r), σ2 is the pooled error variance and r is the number of replicates. In the SREG model, the main effects of lines (L) plus the SL are absorbed into the multiplicative component.

The GGE biplot graphically represents L and SL effect present in the multi-site trial data using sites centred data. GGE biplots were used for 1) genotype evaluation, (stable line(s) across all sites, specific adaptable lines for target sites), and 2) site evaluation, (explains discriminative power among lines in target sites).

Results

Identification of Bemisia tabaci species

B. tabaci samples were collected from 12 locations mainly in the North and South of India. Sequence analysis of the mtCOI PCR products from 23 individual females (females were used because of their greater DNA content) revealed the presence of three indigenous B. tabaci species: Asia II 1 in the North, East and sporadically in the South, Asia II 8 predominantly in the South, and Asia1 at only two locations in the South (Table 1). The finding of B. tabaci Asia II 1 in the North in 2012, 2013 and 2014 and B. tabaci Asia II 8 in the South in 2012 and 2014 indicates a stable situation. The invasive species MEAM1 and MED were not detected in this study.

Detection of begomoviruses

Symptomatic leaf samples were collected from 27 locations mainly from V. radiata and V. mungo in India 2012–2014 (Table 2).

With exceptions MYMV and MYMIV strains were detected in symptomatic mungbean and urdbean leaves from all locations (Table 2). In the Northern Indian states of Punjab and Delhi MYMV-Urdbean (e.g. In-II-P-12-10 DNA-A has 99.5% identity to JQ398669; In-II-P-12-15 DNA-B has 99.5% identity to JQ398670) was found to be dominant in three consecutive years while in Jharkhand state (Eastern India) MYMIV was found showing the highest similarity to a MYMIV-Bengal isolate (eg. IN-P-13-45 DNA-A has 98.3% identity to HF922628; DNA-B not detected). In the Southern Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Telengana MYMV-Vigna (In-P-12-2 DNA-A has 99.7% identity to AJ132575; In-P-12-2 DNA-B has 97.9% identity to AJ439059) was found. Beta-satellites were not detected associated with MYMV or MYMIV in this study. The range of symptom severities observed in susceptible lines at each collection site indicated that symptom severity was related to time of infection rather than to differences in strain or species of yellow mosaic virus present.

Other begomoviruses were detected in leaf samples from some weeds displaying virus-like symptoms: Vernonia yellow vein virus (In-P-12-10 DNA-A has 98.9% identity to AM182232) in a garden land weed and Jatropha leaf yellow mosaic Katarniaghat virus (In-P-12-9 DNA-A has 94.7% identity to JN135236; probably a strain of Jatropha yellow mosaic India virus) in Acalypha indica in the South. In Cassia leaves from the East (Jharkhand) French bean leaf curl virus and an associated beta satellite were detected showing greatest similarity to FbLCV-Kanpur isolate and beta satellite found in Phaseolus vulgaris in the North (In-II-P-14-20 DNA-A has 95.6% identity to JQ866297; In-II-P-14-20 DNA-β has 94.1% identity to JQ866298; Naimuddin et al. 2013).

Screening mungbean lines (Vigna radiata) for reaction to yellow mosaic in the field

During the spring 2012 season crop at Ludhiana there was no incidence of yellow mosaic and hence no data were recorded. In the other 2012 trials, mean yellow mosaic severity scores ranged from 2.0 to 4.9 at Tirunelveli, from 1.0 to 6.0 at Ludhiana and from 2.0 to 6.0 at New Delhi (Table 3.). Average seed yield at Tirunelveli ranged from 0.1 to 2.8 g per plant, and seed yield was not recorded from the Ludhiana and New Delhi trials. In the Tirunelveli trial, lines VC6372 (45–8-1) and ML 818 were the most promising, with mean severity score of 2 (Table 3). ML 818 also recorded reasonable seed yield of 1.8 g/plant. The correlation between yellow mosaic score severity and seed yield was highly significant and negative (−0.42**; P < 0.001) at the Tirunelveli site. In Ludhiana, ML 1628 and ML 1299 were the only lines that recorded yellow mosaic severity mean score of <2 among all the mungbean lines screened. In New Delhi, ML 1628 and ML 1666 recorded yellow mosaic severity mean score of 2 (Table 3). The pooled analysis of variance indicated significant line and site x line interaction for yellow mosaic response during 2012 (Table 7).

In the 2013 Ludhiana trial, several lines (IPM 02–14, IPM 205–7, IPM 02–17, ML 1299, ML 1628, , PDM 139, black gram line (Mash1–1) and the rice bean line (RBL-6)) displayed mean yellow mosaic severity scores of 2 or less (Table 5). The highest mean seed yield was recorded for the black gram line, Mash1–1 (12 g/plant). Among the mungbean lines significantly higher seed yields were recorded from IPM 02–14, IPM 205–7, IPM 02–17, ML 1299 and ML 1628 (Table 5). The correlation between the yellow mosaic severity score and seed yield at the site was significant and negative (−0.82**; P < 0.001). In New Delhi in 2013, VC6369 (53–97), ML 1628, IPM 02–17 and the black gram line, Mash1–1 recorded the lowest yellow mosaic severity scores among all the lines, though the symptom severity scores were still moderate at between 3 and 3.3. Among these lines presenting moderate symptom severities, the highest seed yield was recorded for VC6369 53–97 (4.3 g/plant), followed by ML 1628 and IPM 02–17 (Table 5). The correlation between the yellow mosaic severity score and seed yield at New Delhi was significant and negative (−0.78**; P < 0.001). The pooled analysis of variance for the trials in Ludhiana and New Delhi in 2013 (Table 8) indicated significant site, line and site x line interaction for yellow mosaic response. The pooled analysis of variance on seed production in 2013 (Table 9) also indicated significant site, line and site x line interaction.

In the Odisha trial in 2014, more than half of the lines tested (25/40) developed only mild to very mild (≤ 2.6) yellow mosaic symptoms. Similarly, in the Andhra Pradesh trial in 2014, 19 out of 45 lines presented mild to very mild symptoms (≤ 2.3). The popular mungbean lines NM 92 and NM 94 were included among the lines presenting the mildest symptoms at both these sites (Table 6) Seed yield per plant was not collected from either trial in 2014. Significant line and line x site interaction effects were obtained in the pooled analysis of variance of the Odisha and Andhra Pradesh trials (Table 10).

When GGE Biplot analysis was applied to the 2012 trial data, the first two principal components PC1 and PC2 explained 86.17% of variation (65.80% and 20.37% respectively) for the yellow mosaic ratings (Fig. 1). Lines PAU 911 (ID No. 29), PDM 139 (ID No. 44) and IPM 205–7 (ID No. 46) were the most stable across the three sites. Lines ML 1299 (ID No. 26) and ML 1628 (ID No. 27) are specific adaptable lines for Ludhiana, while VC6368(46–40-4) (ID No. 19), ML 1666 (ID No. 28) and IPM 02–14 (ID No. 43) are some of the specifically adaptable lines for New Delhi. Lines CN 9–5 (ID No. 3), KPS-2 ((ID No. 6) and VC6173A (ID No. 14) recorded high mean scores across the three sites (universally susceptible). From the biplot site (S) evaluation, the New Delhi and Ludhiana sites were the highly discriminative sites, which explained more variation in the lines and these two vectors formed an acute angle (<90o), and line ranks were very similar at both the sites. Tirunelveli had the shortest vector (was less discriminative) and explained little of the variation among lines.

Discussion

Yellow mosaic disease remains a major constraint to mungbean production in most of India, and developing mungbean varieties with resistance or tolerance to the causal virus(es) is a challenge. Although there have been several reports on the incidence of mungbean yellow mosaic from different parts of India, there have been no comprehensive studies looking at the virus species identity and diversity in relation to the B. tabaci species identity and abundance, and the host plant resistance.

An efficient and sustainable management of mungbean yellow mosaic disease includes the control of the virus vector. As B. tabaci species differ significantly in their sensitivity to insecticides with the invasive species MEAM1 and MED having a high propensity for developing resistance against many pesticides (Horowitz et al. 2007; Horowitz and Ishaaya 2014), a comprehensive knowledge of whitefly species abundance is essential for a rational use of insecticides to avoid ineffective protection measures that burden farmer’s health and environment. In recent more extensive investigations of B. tabaci species distribution in India Ellango et al. (2015) and Prasanna et al. (2015) found the indigenous Asia II 1 genotype in high abundance confirming the finding of Asia II 1 in three consecutive years in the North in this study. In another study, Asia1 was found to be predominant in the North of India, butin the South a higher diversity of B. tabaci species was found (Chowda-Reddy et al. 2012; Ellango et al. 2015), whereas in this study Asia II 8 was predominant in the south. A first report of B. tabaci MEAM1 in India was from Banks et al. (2001) who collected this invasive species from infected tomato in the Kolar district. Further reports of MEAM1 were primarily from the same region (Rekha et al. 2005; Shankarappa et al. 2007; Ellango et al. 2015) with one find in Dabhoi in the West (Chowda-Reddy et al. 2012). In all cases MEAM1 were collected from tomato plants suggesting this species may have a preference for solanaceous hosts compared to legumes, though MEAM1 usually is reported to have a very broad host range. Host preference of different whitefly species and a better performance depending on the host were described earlier (Lisha et al. 2003; Xu et al. 2011; Ahmed et al. 2013; Ahmed et al. 2014). MEAM1 was not found in this study, and nor in the study by Prasanna et al. (2015). In both studies the focus was on whiteflies collected from legume hosts. Therefore, there might have been a bias to the indigenous B. tabaci species. However, as no MEAM1 was found in both recent studies and Ellango et al. (2015) found it only in a very restricted region the rapid invasion of MEAM1 in south India suggested by Rekha et al. (2005) appears not to have occurred. To date there is no report of the invasive MED in India.

Over the three consecutive years of this study, only yellow mosaic strains most similar to MYMV-Urdbean were detected in V. radiata, V. mungo and G. max in the North of India, whereas Bag et al. (2014) had previously detected both MYMV and MYMIV at the New Delhi site. Similarly, only strains most similar to MYMV-Vigna were detected in V. radiata and V. mungo in Southern India, and this is as was reported for Vamban (Tamil Nadu) previously (Karthikeyan et al. 2004). Also, MYMIV strains were commonly detected in the East of India as previously reported by Malathi and John (2008). Although these findings may suggest a coincidence of B. tabaci Asia II 1 and MYMV-urdbean in the north of India and Asia II 8 or Asia 1 and MYMV-Vigna or MYMIV in the south and East of the country, more extensive and systematic surveying and identification of the whiteflies and viruses is required in order to confirm or refute this. If it was confirmed, then the next step would be to determine if the predominant B. tabaci species in an area (e.g. Asia II 1 in the North of India) transmit the predominant MYMV strains there with a greater efficiency than the B. tabaci species from a different area. This was shown to be the case for Vietnam where the indigenous B. tabaci Asia II 1 transmitted the indigenous Tomato leaf curl Hainan virus (ToLCHnV) more efficiently than the invading Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV), whereas the invading MEAM1 whiteflies transmitted the TYLCV at greater efficiency than the ToLCHnV (Götz and Winter 2016).

It may be speculated that weed plants play a role in the epidemiology of these viruses by possibly acting as alternative host for virus and/or vector whiteflies (Paul et al. 2012; Barreto et al. 2013). Indeed, Naimuddin et al. (2014) suggested that Ageratum conyzoides, a common weed around the agricultural fields throughout the years is often seen with yellow vein symptoms which might serve as source of primary inoculum of virus for recurrence of yellow mosaic disease in grain legumes. However, too few weed samples displaying virus-like symptoms were collected in this study and because neither MYMV or MYMIV were detected in any of those samples, there is insufficient data to conclude anything on this.

Apart from an effective control of the virus vector B. tabaci breeding varieties with resistance or tolerance to yellow mosaic viruses will provide the most sustainable means for managing the disease (Karthikeyan et al. 2014). In mungbean crop improvement program, the development of the NM varieties, namely NM 92 and NM 94, was the major breakthrough to tackle the problem of MYMD (Ali et al. 1997; Shanmugsundaram et al. 2009). The area under mungbean cropping as well as the seasons in which it is cultivated has been on the increase. For example, the development of the early (about 60 days) maturing varieties such as NM 94 (SML 668) has enabled farmers to grow mungbean as part of the rice-wheat cropping system predominant in the Indo-Gangetic plains. The observed susceptibility of NM 94 in some parts of India during certain seasons (unpublished) prompted us to undertake a comprehensive study on this subject.

This study confirmed the susceptibility of line NM 94 during the Kharif season in Northern parts of India, but also showed it to be relatively tolerant to yellow mosaic in the eastern state of Odisha and the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, and moderately tolerant in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. These results indicated that the tolerance in NM 94 still was effective in the field against local isolates of Mungbean yellow mosaic India virus, genetically most similar to the MYMIV Bengal isolate [HF922628] found in West Bengal and in this study in Jharkhand, and to local isolates of Mungbean yellow mosaic virus genetically most similar to the “Vigna” strains found in this study and also reported by Karthikeyan et al. (2004) in the South of India. The reduced tolerance (susceptibility) of NM 94 in the field in Northern India during the Kharif season may be due to the greater inoculum pressure under these conditions as whitefly populations might build up to very high levels during this time (Varma et al. 2011).

In the field screening, clear differences in symptom severity scores for the same line were observed depending on the year and on the location of the trial. For Ludhiana 2012/2013 and New Delhi 2012/2013 score differences of up to 1.6 were observed for the same line at the same location in different years, and greater differences were observed between locations. These features were highlighted in the GGE biplot analysis which also identified that some lines such as ML1628 and ML1229 may be better adapted and more tolerant to yellow mosaic in the Kharif season in the north, whereas other lines such as VC6368 46–40-4 were better adapted to the south.

In general, the average symptom severity scores were greater in the trials in the north of India where the MYMV-Urdbean like strains predominant compared to the south and east where the MYMV-Vigna like strains and MYMIV strains were present respectively. The analysis suggests that this difference is due to the interaction of environment (north - south) and virus species/strains.

The identification of high level of tolerance or resistance in lines such as ML 1628 and from the closely related species, V. mungo und V. umbellata under high inoculum pressure in the field offers hope for breeders to tackle the disease through host plant resistance. Also, the performance of mungbean lines IPM 02–17 and ML 1628 with lower severity scores as well as comparatively higher seed yields particularly in North India are good options for farmers to cope with the disease during the Kharif season. The significant negative correlation between disease severity score and seed yield in both Ludhiana and New Delhi also strongly support the possibility of selection of disease resistant plants with relatively high seed yield. Efforts are in progress to map the resistance genes in NM 94 and to compare them with those of ML 1628. In order to achieve this, mapping populations have been developed with both NM 94 and ML 1628.

The results reported in this paper have highlighted the predominant whitefly species and the major virus species responsible for transmitting and inducing yellow mosaic disease in mungbean in India. It has also identified mungbean lines with a high levels of field resistance for different locations of the country, and this will help breeders to select the appropriate parents in their breeding programs and also the farmers in the selection of appropriate varieties for sowing.

References

Ahmed, M. Z., De Barro, P. J., Ren, S. X., Greeff, J. M., & Qiu, B. L. (2013). Evidence for horizontal transmission of secondary endosymbionts in the Bemisia tabaci cryptic species complex. PloS One, 8(1–10), e53084. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053084.

Ahmed, M. Z., Naveed, M., Noo rul Ane, M., Ren, S. X., De Barro, P., & Qiu, B. L. (2014). Host suitability comparison between the MEAM1 and AsiaII 1 cryptic species of Bemisia tabaci in cotton-growing zones of Pakistan. Pest Management Science, 70, 1531–1537. doi:10.1002/ps.3716.

Akhtar, K. P., Kitsanachandee, R., Srinives, P., Abbas, G., Asghar, M. J., Shah, T. M., Atta, B. M., Chatchawankanphanich, O., Sarwar, G., Ahmad, M., & Sarwar, N. (2009). Field evaluation of mungbean recombinant inbred lines against mungbean yellow mosaic disease using new disease scale in Thailand. Plant Pathology Journal, 25(4), 422–428. doi:10.5423/PPJ.2009.25.4.422.

Akram, M., Naimuddin, Agnihotri, A. K., Gupta, S., & Singh, N. P. (2015). Characterization of full genome of Dolichos yellow mosaic virus based on sequence comparison, genomic region and phylogenic relationship. Annals of Applied Biology, 167(3), 354–363.

Alam, A. K. M., Somta, P., & Srinives, P. (2014). Generation mean and path analyses of reaction to mungbean yellow mosaic virus (MYMV) and yield-related traits in mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.)Wilczek). SABRAO Journal of Breeding and Genetics, 46(1), 150–159.

Ali, M., Malik, I. A., Sahir, H. M., & Bashir, A. (1997). The mungbean green revolution in Pakistan. Technical bulletin no. 24. Shanhua: The World Vegetable Center (AVRDC).

Bag, M. K., Gautam, N. K., Prasad, T. V., Pandey, S., Dutta, M., & Roy, A. (2014). Evaluation of an Indian collection of black gram germplasm and identification of resistance sources to mungbean yellow mosaic virus. Crop Protection, 61, 92–101. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2014.03.021.

Banks, G. K., Colvin, J., Chowda-Reddy, R. V., Maruthi, M. N., Muniyappa, V., Venkatesch, H. M., Kiran Kumar, M., Padmaja, A. S., Beitia, F. J., & Seal, S. E. (2001). First report of Bemisia tabaci B biotype in India and an associated tomato leaf curl virus disease epidemic. Plant Disease, 85, 231. doi:10.1094/PDIS.2001.85.2.231C.

Barreto, S. S., Hallwass, M., Aquino, O. M., & Inoue-Nagata, A. K. (2013). A study of weeds as potential inoculum sources for a tomato-infecting begomovirus in Central Brazil. Phytopathology, 103(5), 436–444. doi:10.1094/PHYTO-07-12-0174-R.

Boykin, L. M., & De Barro, P. (2014). A practical guide to identifying members of the Bemisia tabaci species complex: And other morphologically identical species. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 2, 45. doi:10.3389/fevo.2014.00045.

Briddon, R. W., Prescott, A. G., Lunness, P., Chamberlin, L. C. L., & Markham, P. G. (1993). Rapid production of full-length, infectious geminivirus clones by abutting primer PCR (AbP-PCR). Journal of Virological Methods, 43, 7–20. doi:10.1016/0166-0934(93)90085-6.

Briddon, R. W., Bull, S. E., Mansoor, S., Amin, I., & Markham, P. G. (2002). Universal primers for the PCR-mediated amplification of DNA beta - a molecule associated with some monopartite begomoviruses. Molecular Biotechnology, 20(3), 315–318. doi:10.1385/MB:20:3:315.

Chowda-Reddy, R. V., Kirankumar, M., Seal, S. E., Muniyappa, V., Valand, G. B., Govindappa, M. R., & Colvin, J. (2012). Bemisia tabaci phylogenetic groups in India and the relative transmission efficacy of tomato leaf curl Bangalore virus by an indigenous and an exotic population. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 11, 235–248. doi:10.1094/PDIS.2001.85.2.231C.

De Barro, P. & Boykin, L. (2013) Global Bemisia dataset release version CSIRO, v1. edn. Data Collection, doi:10.4225/08/50EB54B6F1042.

Dhole, V. J., & Reddy, K. S. (2012). Genetic analysis of resistance to mungbean yellow mosaic virus in mungbean (Vigna radiata). Plant Breeding, 131, 414–417. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0523.2012.01964.x.

Dhole, V. J., & Reddy, K. S. (2013). Development of a SCAR marker linked with a MYMV resistance gene in mungbean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek). Plant Breeding, 132, 127–132. doi:10.1111/pbr.12006.

Dinsdale, A., Cook, L., Riginos, C., Buckley, Y. M., & De Barro, P. (2010). Refined global analysis of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Aleyrodoidea: Aleyrodidae) mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase 1 to identify species level genetic boundaries. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 103(2), 196–208. doi:10.1603/AN09061.

Ellango, R., Singh, S. T., Rana, V. S., Priya, N. G., Raina, H., Chaubery, R., Naveen, N. C., Mahmood, R., Ramamurthy, V. V., Asokan, R., & Rajagopal, R. (2015). Distribution of Bemisia tabaci genetic groups in India. Environmental Entomology, 44(4), 1258–1264. doi:10.1093/ee/nvv062.

Frohlich, D. R., Torres-Jerez, I., Bedford, I. D., Markham, P. G., & Brown, J. K. (1999). A phylogeographical analysis of the Bemisia tabaci species complex based on mitochondrial DNA markers. Molecular Ecology, 8(10), 1683–1691. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00754.x.

Götz, M., & Winter, S. (2016). Diversity of Bemisia tabaci in Thailand and Vietnam and indications of species replacement. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology, 19(2), 537–543. doi:10.1016/j.aspen.2016.04.017.

Guo, T., Guo, Q., Cui, X.-Y., Liu, Y.-Q., Hu, J., & Liu, S. S. (2015). Comparison of transmission of papaya leaf curl China virus among four cryptic species of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci Complex. Scientific Reports, 5(15432), 1–9. doi:10.1038/srep15432.

Horowitz, A. R., & Ishaaya, I. (2014). Dynamics of biotypes B and Q of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci and its impact on insecticide resistance. Pest Management Science, 70, 1568–1572. doi:10.1002/ps.3752.

Horowitz, R., Denholm, I., & Morin, S. (2007). Resistance to insecticides in the TYLCV vector, Bemisia Tabaci. In H. Czosnek (Ed.), Tomato yellow leaf curl virus disease (pp. 305–325). Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4769-5_18.

Ilyas, M., Qazi, J., Mansoor, S., & Briddon, R. W. (2009). Molecular characterisation and infectivity of a "legumovirus" (genus Begomovirus: Family Geminiviridae) infecting the leguminous weed Rhynchosia minima in Pakistan. Virus Research, 145(2), 279–284. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2009.07.018.

Karthikeyan, A. S., Vanitharani, R., Balaji, V., Anuradha, S., Thillaichidambaram, P., Shivaprasad, P. V., Parameswari, C., Balamani, V., Saminathan, M., & Veluthambi, K. (2004). Analysis of an isolate of mungbean yellow mosaic virus (MYMV) with a highly variable DNA B component. Archives of Virology, 149(8), 1643–1652. doi:10.1007/s00705-004-0313-z.

Karthikeyan, A., Shobhana, V. G., Sudha, M., Raveendran, M., Senthil, N., Pandiyan, M., & Nagarajan, P. (2014). Mungbean yellow mosaic virus (MYMV): A threat to green gram (Vigna radiata) production in Asia. International Journal of Pest Management, 60(4), 314–324. doi:10.1080/09670874.2014.982230.

Lisha, V. S., Antony, B., Palaniswami, M. S., & Henneberry, T. J. (2003). Bemisia Tabaci (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae) biotypes in India. Journal of Economic Entomology, 96, 322–327. doi:10.1093/jee/96.2.322.

Maiti, S., Basak, J., Kundagrami, S., Kundu, A., & Pal, A. (2011). Molecular marker-assisted genotyping of mungbean yellow mosaic India virus resistant germplasms of mungbean and urdbean. Molecular Biotechnology, 47, 95–104. doi:10.1007/s12033-010-9314-1.

Malathi V.G., John, P. (2008) Mungbean yellow mosaic viruses. In B. W. J. Mahy & M. H. V van Regenmortel (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Virology, 3rd ed, (pp. 364–372). doi:10.1016/B978-012374410-4.00708-1.

Malik, I.A., Ali, Y. & Saleem, M. (1988) Incorporation of tolerance to mungbean yellow mosaic virus from local germplasm to exotic large seeded mungbean. In S. Shanmungasundrum (Ed.), Mungbean: Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Mungbean (pp. 297–307). Bangkok, Thailand, Taiwan, ROC: AVRDC. 16–20 November 1987.

Markham, P. G., Bedford, I. D., Liu, S., & Pinner, M. S. (1994). The transmission of geminiviruses by Bemisia tabaci. Pesticide Science, 42, 123–128. doi:10.1002/ps.2780420209.

Naimuddin, K., Akram, M., & Gupta, S. (2011). Identification of Mungbean yellow mosaic India virus infecting Vigna mungo Var. silvestris L. Phytopathologia Mediterranea, 50, 94–100. doi:10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-8740.

Naimuddin, K., Akram, M., Pratap, A., & Yadav, P. (2013). Characterization of a new begomovirus and a beta satellite associated with the leaf curl disease of French bean in northern India. Virus Genes, 46, 120–127. doi:10.1007/s11262-012-0832-8.

Naimuddin, A. M., Gupta, S., & Agnihotri, A. K. (2014). Ageratum conyzoides harbours mungbean yellow mosaic India virus. Plant Pathology Journal, 13(1), 59–64.

Nair, R. M., Schafleitner, R., Kenyon, L., Srinivasan, R., Easdown, W., Ebert, A. W., & Hanson, P. (2012). Genetic improvement of mungbean. SABRAO Journal of Breeding and Genetics, 44(2), 177–190.

Ning, W., Shi, X., Liu, B., Pan, H., Wei, W., Zeng, Y., Sun, X., Xie, W., Wang, S., Wu, Q., Cheng, J., Peng, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2015). Transmission of tomato yellow leaf curl virus by Bemisia tabaci as affected by whitefly sex and biotype. Scientific Reports, 5(10744), 1–8. doi:10.1038/srep10744.

Pan, H., Chu, D., Yan, W., Su, Q., Liu, B., Wang, S., Wu, Q., Xie, W., Jiao, X., Li, R., Yang, N., Yang, X., Xu, B., Brown, J. K., Zhou, X., & Zhang, Y. (2012). Rapid spread of tomato yellow leaf curl virus in China is aided differentially by two invasive whiteflies. PloS One, 7(1–9), e34817. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034817.

Paul, S., Ghosh, R., Roy, A., & Ghosh, S. K. (2012). Analysis of coat protein gene sequences of begomoviruses associated with different weed species in India. Phytoparasitica. doi:10.1007/s12600-011-0202-4.

Poehlman, J. M. (1991). The mungbean. Boulder: Westview Press.

Prasanna, H. C., Kanakala, S., Archana, K., Jyothsna, P., Varma, R. K., & Malathi, V. G. (2015). Cryptic species composition and genetic diversity within Bemisia tabaci Complex in soybean in India revealed by mtCOI DNA sequence. Journal of Integrative Agriculture. doi:10.1016/s2095-3119(14)60931-x.

Rekha, W. R., Maruthi, M. N., Muniyappa, V., & Colvin, J. (2005). Occurrence of three genotypic clusters of Bemisia Tabaci and the rapid spread of the B biotype in South India. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 117, 221–233. doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.2005.00352.x.

Ronquist, F., Teslenko, M., van der Mark, P., Ayres, D. L., Darling, A., Höhna, S., Larget, B., Liu, L., Suchard, M. A., & Huelsenbeck, J. P. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Systematic Biology, 61, 539–542. doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys029.

Sandhu, T. S., Brar, J. S., Sandhu, S. S., & Verma, M. M. (1985). Inheritance of resistance to mungbean yellow mosaic virus in greengram. J Res (Punjab Agric Univ), 22, 607–611.

Selvi, R., Muthiah, A. R., Manivannan, N., Raveendran, T. S., Manickam, A., & Samiyappan, R. (2006). Tagging of RAPD .Marker for MYMV resistance in mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek). Asian Journal of Plant Sciences, 5, 277–280.

Shankarappa, K. S., Rangaswamy, K. T., Narayana, D. S. A., Rekha, A. R., & Raghavendra, N. (2007). Development of silver leaf assay, protein and nucleic acid-based diagnostic techniques for the quick and reliable detection and monitoring of biotype B of the whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius). Bulletin of Entomological Research, 97, 503–513. doi:10.1017/S0007485307005251.

Shanmugsundaram, S., Keatinge, J.D.H. & Hughes, Jd’A. (2009) The mungbean transformation, diversifying crops, defeating malnutrition. IFPRI Discussion Paper 00922 p. 43 http://www.ifpri.org/millionsfed

Shukla, G. P., & Pandya, B. P. (1985). Resistance to yellow mosaic in greengram. SABRAO Journal of Breeding and Genetics, 17, 165–171.

Singh, B. V., & Ahuja, M. R. (1977). Phaseolus sublobatus Roxb. A source of resistance to yellow mosaic virus for cultivated mung. Indian Journal of Genetics and Plant Breeding, 37, 130–132.

Singh, D., & Patel, P. N. (1977). Studies on resistance in crops to bacterial diseases in India. 8. Investigations on inheritance of reactions to bacterial leaf spot and yellow mosaic diseases and linkage, if any, with other characters in mungbean. Indian Phytopathology, 30(2), 202–206.

Somta, P., Seehalak, W., & Srinives, P. (2009). Development, characterization and cross-species amplification of mungbean (Vigna radiata) genic microsatellite markers. Conservation Genetics, 10, 1939–1943.

Souframanien, J., & Gopalakrishna, T. (2006). ISSR and SCAR markers linked to the mungbean yellow mosaic virus (MYMV) resistance gene in blackgram [Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper]. Plant Breeding, 125, 619–622. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0523.2006.01260.x.

Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G., & Gibson, T. J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research, 22(22), 4673–4680. doi:10.1093/nar/22.22.4673.

Tsai, W. S., Shih, S. L., Rauf, A., Safitri, R., Hidayati, N., Huyen, B. T. T., & Kenyon, L. (2013). Genetic diversity of legume yellow mosaic begomoviruses in Indonesia and Vietnam. Annals of Applied Biology, 163(3), 367–377. doi:10.1111/aab.12063.

Varma, A., Mandal, B., & Singh, M. K. (2011). Global emergence and spread of whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) transmitted viruses. In W. M. O. Thomson (Ed.), The whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Homoptera: Aleurodidae) interaction with geminivirus-infected host plants (pp. 205–292). Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-1524-0_10.

Xu, J., Lin, K., & Liu, S. S. (2011). Performance on different host plants of an alien and an indigenous Bemisia tabaci from China. Journal of Applied Entomology, 135, 771–779. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0418.2010.01581.x.

Yan, W., & Tinker, N. A. (2006). Biplot analysis of multi-environment trial data: Principles and applications. Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 86, 623–645. doi:10.4141/P05-169.

Zhang, W. M., Fu, H. B., Wang, W. H., Piao, C. S., Tao, Y. L., Guo, D., & Chu, D. (2014). Rapid spread of a recently introduced virus (tomato yellow leaf curl virus) and its vector Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in Liaoning province, China. Journal of Economic Entomology, 107, 98–104. doi:10.1603/EC13348.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following for providing some of the lines used in this study: Indian Institute of Pulses Research, Kanpur, India (IPM 99-125, IPM 02-3, IPM 02-14, IPM 409-4, IPM 205-7, IPM 02-17, IPM 02-19, IPM 9901-6, IPM 9901-10 and PDM 139), Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana, India (ML 613, ML 818, ML 1299, ML 1628, ML 1666, PAU 911, SML 823, SML 832, SML 843, SML 1018, SML 1074, Mash1-1 and RBL-6), and Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, India ( CO. 5, CO. 6, CO (G9)-7, VBN(G9)-2 and VBN(G9)-3). This study was funded in part through the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Project no. 81141863.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 23 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nair, R.M., Götz, M., Winter, S. et al. Identification of mungbean lines with tolerance or resistance to yellow mosaic in fields in India where different begomovirus species and different Bemisia tabaci cryptic species predominate. Eur J Plant Pathol 149, 349–365 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-017-1187-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-017-1187-8