Abstract

Although keeping a healthy weight and being physically active are among the few modifiable risk factors for post-menopausal breast cancer, the possible interaction between these two risk factors remains to be established. We analyzed prospectively a cohort of 19,196 women who provided detailed self-report on anthropometric measures, physical activity and possible confounders at enrollment in 1997. We achieved complete follow-up through 2010 and ascertained 609 incident cases of post-menopausal invasive breast cancer. We calculated metabolic energy turnover (MET h/day) per day and fitted Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). The incidence of post-menopausal breast cancer among obese women (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) was 58 % higher (HR 1.58, CI 1.16–2.16) than in women of normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 25). Women in the lowest tertile of total physical activity (< 31.2 MET h/day) had 40 % higher incidence of post-menopausal breast cancer (HR 1.40, CI 1.11–1.75) than those in the highest tertile (≥ 38.2 MET h/day). The excess incidence linked to these two factors seemed to combine in an approximately additive manner; the incidence among the most obese and sedentary women was doubled (HR 2.07, CI 1.31–3.25) compared with the most physically active women with normal weight. No heterogeneity of the physical activity-linked risk ratios across strata of BMI was detected (p value for interaction = 0.98). This prospective study revealed dose-dependent, homogenous inverse associations between post-menopausal breast cancer incidence and physical activity across all strata of BMI, and between post-menopausal breast cancer incidence and BMI across all strata of physical activity, with no evidence of additive or multiplicative interaction between the two, suggesting independent effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

IARC. Breast cancer estimated incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. Globcan. 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx. Accessed April 30, 2015.

Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, Ward EM. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(8):1893–907. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0437.

Knaul F, Adami H, Adebamowo C, et al. The global cancer divide: an equity imperative. In: Knaul FM, Gralow JR, Atun R, Bhadelia A, editors. Closing the cancer divide: an equity imperative. Boston: Harvard Global Equity Initiative; 2012.

Adami H, Hunter D, Trichopoulos D, editors. Textbook of cancer epidemiology, chapter 16. In: Hankinson S, Tamimi R, Hunter D, editors. Breast cancer. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. p. 403–45.

Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, et al. Alcohol and breast cancer in women: a pooled analysis of cohort studies [see comments]. JAMA. 1998;279(7):535–40.

Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Lancet. 1997;350(9084):1047–59.

Magnusson C, Baron JA, Correia N, Bergstrom R, Adami HO, Persson I. Breast-cancer risk following long-term oestrogen- and oestrogen-progestin-replacement therapy. Int J Cancer. 1999;81(3):339–44.

McCullough LE, Eng SM, Bradshaw PT, et al. Fat or fit: the joint effects of physical activity, weight gain, and body size on breast cancer risk. Cancer. 2012;118(19):4860–8. doi:10.1002/cncr.27433.

Krishnan K, Bassett JK, MacInnis RJ, et al. Associations between weight in early adulthood, change in weight, and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2013;22(8):1409–16. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0136.

Friedenreich CM. Physical activity and breast cancer: review of the epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms. Recent results in cancer research. Fortschritte der Krebsforschung. Progres dans les recherches sur le cancer. 2011;188:125–39. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-10858-7_11.

Lagerros YT, Mucci LA, Bellocco R, Nyren O, Balter O, Balter KA. Validity and reliability of self-reported total energy expenditure using a novel instrument. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(3):227–36.

Lagerros YT, Bellocco R, Adami HO, Nyren O. Measures of physical activity and their correlates: the Swedish National March Cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(4):161–9.

Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(11):659–67. doi:10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y.

Mattsson B, Rutqvist LE. Some aspects on validity of breast cancer, pancreatic cancer and lung cancer registration in Swedish official statistics. Radiother Oncol. 1985;4(1):63–70.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S498–504.

Bexelius C, Lof M, Sandin S, TrolleLagerros Y, Forsum E, Litton JE. Measures of physical activity using cell phones: validation using criterion methods. J Medical Internet Res. 2010;12(1):165–70.

Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome—a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005;366(9491):1059–62.

Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i–xii, 1–253.

Knol MJ, VanderWeele TJ. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(2):514–20. doi:10.1093/ije/dyr218.

Knol MJ, van der Tweel I, Grobbee DE, Numans ME, Geerlings MI. Estimating interaction on an additive scale between continuous determinants in a logistic regression model. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(5):1111–8. doi:10.1093/ije/dym157.

Knol MJ, Egger M, Scott P, Geerlings MI, Vandenbroucke JP. When one depends on the other: reporting of interaction in case-control and cohort studies. Epidemiology. 2009;20(2):161–6. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818f6651.

Van der Weele T. Explanation in causal inference: methods for mediation and interaction. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15(4):361–87. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361:AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4.

van Buuren S, Boshuizen HC, Knook DL. Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):681–94.

Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation for interval estimation from simple random samples with ignorable nonrespons. J Am Stat Assoc. 1986;81:366–74.

Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington, DC: AICR: World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007.

Harvie M, Hooper L, Howell AH. Central obesity and breast cancer risk: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2003;4(3):157–73.

Wu Y, Zhang D, Kang S. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(3):869–82. doi:10.1007/s10549-012-2396-7.

Zhong S, Jiang T, Ma T, et al. Association between physical activity and mortality in breast cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(6):391–404. doi:10.1007/s10654-014-9916-1.

Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371(9612):569–78. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X.

McTiernan A, Kooperberg C, White E, et al. Recreational physical activity and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Cohort Study. JAMA. 2003;290(10):1331–6. doi:10.1001/jama.290.10.1331.

Carpenter CL, Ross RK, Paganini-Hill A, Bernstein L. Lifetime exercise activity and breast cancer risk among post-menopausal women. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(11):1852–8.

Slattery ML, Edwards S, Murtaugh MA, et al. Physical activity and breast cancer risk among women in the southwestern United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(5):342–53. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.017.

Enger SM, Ross RK, Paganini-Hill A, Carpenter CL, Bernstein L. Body size, physical activity, and breast cancer hormone receptor status: results from two case-control studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9(7):681–7.

Thune I. Assessments of physical activity and cancer risk. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2000;9(6):387–93.

Maruti SS, Willett WC, Feskanich D, Rosner B, Colditz GA. A prospective study of age-specific physical activity and premenopausal breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(10):728–37. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn135.

Colditz GA, Feskanich D, Chen WY, Hunter DJ, Willett WC. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer in premenopausal women. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(5):847–51. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601175.

Shoff SM, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Early-life physical activity and postmenopausal breast cancer: effect of body size and weight change. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9(6):591–5.

Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS Jr, Lee IM. Physical activity and breast cancer risk in the College Alumni Health Study (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9(4):433–9.

Breslow RA, Ballard-Barbash R, Munoz K, Graubard BI. Long-term recreational physical activity and breast cancer in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I epidemiologic follow-up study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10(7):805–8.

Moore DB, Folsom AR, Mink PJ, Hong CP, Anderson KE, Kushi LH. Physical activity and incidence of postmenopausal breast cancer. Epidemiology. 2000;11(3):292–6.

Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Chute CG, Litin LB, Willett WC. Validity of self-reported waist and hip circumferences in men and women. Epidemiology. 1990;1(6):466–73.

Soto Gonzalez A, Bellido D, Buno MM, et al. Predictors of the metabolic syndrome and correlation with computed axial tomography. Nutrition. 2007;23(1):36–45. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2006.08.019.

McTiernan A. Physical activity and the prevention of breast cancer. Medscape Womens Health. 2000;5(5):E1.

Pizzi C, De Stavola BL, Pearce N, et al. Selection bias and patterns of confounding in cohort studies: the case of the NINFEA web-based birth cohort. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2012;66(11):976–81. doi:10.1136/jech-2011-200065.

Lynch BM, Neilson HK, Friedenreich CM. Physical activity and breast cancer prevention. Recent results in cancer research. Fortschritte der Krebsforschung. 2011;186:13–42. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-04231-7_2.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Statistics Sweden for scanning the questionnaires. Furthermore, we would like to express sincere gratitude to the Swedish Cancer Society and volunteers who worked with the National March. This work was supported by ICA AB; Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson; the Swedish Cancer Society [CAN 2012/591 to H–O.A.]; Karolinska Institutet Distinguished Professor Award [2368/10-221 to H–O.A.]; and the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet [to Y.T.L.].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Rino Bellocco and Gaetano Marrone have contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary figure 1a-c

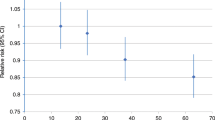

Adjusted Hazard Ratios (HR) of post-menopausal breast cancer in the Swedish National March Cohort according to total physical activity (MET h/day) and stratified by category of body mass index (BMI, the weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters), a) normal weight (18.5≤BMI<25), b) overweight (25≤BMI<30), c) obesity (BMI≥30 kg/m2). The solid lines indicate hazard ratios, and dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals derived from restricted cubic spline regression, with knots placed at the 5th, 25th, 75th, and 95th percentiles of the physical activity distribution. The reference points correspond to the 25th percentile. The graph is truncated and ranges around 90% of the distribution. The hazard ratios are plotted on a logarithmic scale and adjusted for age at enrollment, cigarette smoking status, alcohol drinking, use of vitamin and mineral supplements, education level, contraceptive pill use, hormonal replacement therapy, age at menarche, number of children, age at first full-term pregnancy and childlessness. (DOCX 118 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bellocco, R., Marrone, G., Ye, W. et al. A prospective cohort study of the combined effects of physical activity and anthropometric measures on the risk of post-menopausal breast cancer. Eur J Epidemiol 31, 395–404 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-015-0064-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-015-0064-z