Abstract

Background

Wnt-β-catenin signaling is essential for homeostasis of intestinal stem cells in mice and is thought to promote intestinal crypt fission.

Aims

The aim of this study was to investigate Wnt-β-catenin signaling in intestinal crypts of human infants.

Methods

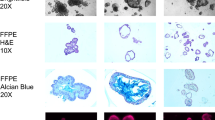

Duodenal biopsies from nine infants (mean, range 0.9 years, 0.3–2 years) and 11 adults (mean, range 43 years, 34–71 years) were collected endoscopically. Active β-catenin signaling was assessed by cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin, nuclear c-Myc, and cytoplasmic Axin-2 expression in the base of crypts. Tissues were stained by an immunoperoxidase staining technique and quantified as pixel energy using cumulative signal analysis. Data were expressed as mean ± SD and significance assessed by Student’s t test.

Results

Crypt fission was significantly higher in infants compared to adults (16 ± 8.6% versus 0.7 ± 0.6%, respectively, p < 0.0001). Expression of cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin was 1.8-fold (p < 0.0001) and 2.9-fold (p < 0.0001) higher in infants, respectively, while cytoplasmic Axin-2 was 3.1-fold (p < 0.0001) increased in infants. c-Myc expression was not significantly different between infants and adults. Expression was absent in Paneth cells but present in the transit amplifying zone of crypts. Crypt base columnar cells, which were intercalated between Paneth cells, expressed c-Myc.

Conclusions

Wnt-β-catenin signaling was active in crypt base columnar cells (i.e., intestinal stem cells) in human infants. This signaling could promote crypt fission during infancy. Wnt-β-catenin signaling likely acts in concert with other pathways to promote postnatal growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lieberkühn JN, Dissertatio defabrica et actione villorum intestinorum tenuium hominis (Lugduni Batavorum). MD Thesis, 1745. Museum Boerhave, Lieden.

Cheng H, Bjerknes M. Whole population cell kinetics and postnatal growth of the mouse intestinal epithelium. Anat Rec. 1985;211:420–426.

Herbst JJ, Sunshine P. Postnatal development of the small intestine of the rat: changes in mucosal morphology at weaning. Pediatr Res. 1969;3:27–33.

St Clair WH, Osborne JW. Crypt fission and crypt number in the small and large bowel of postnatal rats. Cell Tissue Kinet. 1985;18:255–262.

Cummins AG, Jones BJ, Thompson FM. Postnatal epithelial growth of the small intestine in the rat occurs by both crypt fission and crypt hyperplasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:718–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-006-3197-9.

Slupecka M, Wolinski J, Pierzynowski S. Crypt fission contributes to postnatal epithelial growth of the small intestine in pigs. Livest Sci. 2010;133:34–37.

Cummins AG, Catto-Smith AG, Cameron RT, et al. Crypt fission peaks early during infancy and crypt hyperplasia broadly peaks during infancy and childhood in the small intestine of humans. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:153–157.

Dehmer JJ, Garrison AP, Speck KE, et al. Expansion of intestinal epithelial stem cells during murine development. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27070.

Wright NA. Epithelial stem cell repertoire in the gut: clues to the origin of cell lineages, proliferation units and cancer. Int J Exp Pathol. 2000;81:117–143.

Fauser JK, Donato RP, Woenig JA, et al. Wnt blockade with dickkopf reduces intestinal crypt fission and intestinal growth in infant rats. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:26–31.

Pinto D, Gregorieff A, Begthel H, Clevers H. Canonical Wnt signals are essential for homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1709–1713.

Sato T, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, et al. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature. 2011;469:415–418.

Langlands AJ, Almet AA, Appleton PL, Newton IP, Osborne JM, Nãthke IS. Paneth cell rich regions-separated by a cluster of Lgr5 + cells initiate crypt fission in intestinal stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2016;14:e1002491.

Drozdowski LA, Clandinin T, Thomson ABR. Ontogeny, growth, and development of the small intestine: understanding pediatric gastroenterology. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:787–799.

Gregorieff A, Pinto D, Begthel H, Destrée O, Kielman M, Clevers H. Expression pattern of Wnt signaling components in the adult intestine. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:626–638.

Valenta T, Degimemci B, Moor AE, et al. Wnt ligands secreted by subepithelial mesenchymal cells are essential for the survival of intestinal stem cells and gut homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2016;15:911–918.

Flanagan DJ, Phesse TJ, Barker N, et al. Frizzled-7 functions as a Wnt receptor in intestinal epithelial Lgr5(+) stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4:759–767.

Dijksterhuis JP, Peterson J, Schulte G. Wnt/frizzled signaling: receptor-ligand selectivity with focus on FZD-G protein signaling and its physiological relevance. IUPHAR Review 3. Br J Pharmol. 2014;171:1195–1209.

van de Wetering M, Sancho E, Verweij C, et al. The β-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell. 2002;111:241–250.

Batlle E, Henderson JT, Begthel H, et al. β-catenin and TCF mediate cell positioning in the intestinal epithelium by controlling the expression of Ephβ/Ephrinβ. Cell. 2002;111:251–263.

Yan D, Wiesmann M, Rohan M, et al. Elevated expression of axin-2 and hnkd mRNA provides evidence that Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is activated in human colon tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14973–14978.

Ferguson A, Sutherland A, MacDonald TT, Allan F. Technique for the microdissection and measurement of biopsies of human small intestine. J Clin Pathol. 1977;30:1068–1073.

Goodlad RA, Wilson TJ, Lenton W, et al. Microdissection–based techniques for the determination of cell proliferation in gastrointestinal epithelium: application to animals and human studies. In: Celis JE, ed. Cell biology: laboratory handbook. New York: Academic Press; 1994:205–206.

Cummins AG, LaBrooy JT, Stanley DP, Rowland R, Shearman D. Quantitative histological study of enteropathy associated with HIV infection. Gut. 1990;31:317–321.

Cummins AG, Alexander BG, Chung A, et al. Morphometric evaluation of duodenal biopsies in celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:145–150.

Matkowskyj KA, Schonfeld D, Benya RV. Quantitative immunohistochemistry by measuring cumulative signal strength using commercial available software Photoshop and Matlab. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:303–311.

Matkowskyj KA, Cox R, Jensen RT, Benya RV. Quantitative immunohistochemistry by measuring cumulative signal accurately measures receptor number. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:205–214.

Camac KS, Thompson FM, Cummins AG. Activation of beta-catenin in the stem cell region of crypts during growth of the small intestine in infant rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1242–1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-006-9200-7.

Gregorief A, Clevers H. Wnt signaling in the intestinal epithelium: from endoderm to cancer. Genes Dev. 2005;19:877–890.

Guezguez A, Paré F, Benoit YD, Bessora N, Beaulieu JF. Modulation of stemness in a human normal intestinal epithelial crypt cell line by activation of the WNT signaling pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2014;322:355–364.

Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265.

Klostermeier UC, Barann W, Wittig M, et al. A tissue-specific landscape of sense/antisense transcription in the mouse intestine. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:305.

Farin HF, Jordens I, Mosa MH, et al. Visualization of a short-range Wnt gradient in the intestinal stem-cell niche. Nature. 2016;530:340–343.

Takeda H, Lyle S, Lazar AJ, et al. Monounsaturated fatty acid modification of Wnt protein: its role in Wnt secretion. Dev Cell. 2006;11:791–801.

Cummins AG, Woenig JA, Donato RP, Proctor SJ, Howarth GS, Grover PK. Notch signaling promotes intestinal crypt fission in the infant rat. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:678–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-012-2422-y.

Fre S, Pallavi SK, Huyghe M, et al. Notch and Wnt signals cooperatively control cell proliferation and tumorigenesis in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6309–6314.

Cheng H, Leblond CP. Origin, differentiation, and renewal of the four main cell types in the mouse small intestine. I. Columnar cell. Am J Anat. 1974;141:461–479.

Potten CS. Stem cells in gastrointestinal epithelium: numbers, characteristics and death. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;353:821–830.

Wright NA, Appleton DR, Marks J, Watson AJ. Cytokinetic studies of crypts in convoluted human small-intestinal mucosa. J Clin Pathol. 1979;32:462–470.

Bettess MD, Dubois N, Murphy MJ, et al. c-Myc is required for the formation of intestinal crypts but dispensable for the homeostasis of the adult intestinal epithelium. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7868–7878.

Rennell SA, Konsavage WM, Yochum GS. Nuclear axin-2 represses Myc gene expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;443:217–222.

Xi CH, Yon T, Grindley JC, et al. PTEN-deficient intestinal stem cells initiate intestinal polyposis. Nat Genetics. 2006;39:189–198.

Funding

Zenab Dudhwala gratefully received a Faculty of Health Science Divisional Scholarship from the University of Adelaide. The authors are grateful for funding from the Private Practice Fund of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Woodville South, SA 5011, Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors had a conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dudhwala, Z.M., Drew, P.A., Howarth, G.S. et al. Active β-Catenin Signaling in the Small Intestine of Humans During Infancy. Dig Dis Sci 64, 76–83 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5286-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5286-y