Abstract

Background

Asymptomatic erosive esophagitis (AEE) is considered an erosive esophagitis without the typical reflux symptoms, but the clinical course and significance of AEE is still unclear.

Aim

We investigated the prevalence and predisposing factors of AEE, and tried to determine its clinical features and significance.

Methods

Subjects, who had at least two health inspections (upper endoscopy, self-reporting questionnaire, and serum Helicobacter pylori IgG antibody test) at our center, were enrolled. The questionnaire included typical reflux symptoms, previous medical history, underlying disease, smoking, alcohol intake, and medication history. Based on the results of follow-up study, the changes in endoscopic findings and reflux symptoms were also investigated.

Results

Of the 2961 patients visiting our clinic, 568 (19.2 %) were diagnosed with AEE. Age over 50 years, male sex, a body mass index over 25, current smoking, heavy drinking, negativity for H. pylori infection, and hiatal hernia were independent predisposing factors for AEE (p = 0.020, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p = 0.013, p = 0.003, p < 0.001, p = 0.038, respectively). Within the follow-up period (mean 25 ± 9.5 months), reflux symptoms developed in 30 subjects (7.9 %), and current smoking was the only risk factor for the development of AEE symptoms (p = 0.015). On the follow-up endoscopy, erosive esophagitis disappeared in nearly half of the subjects with AEE (174, 45.6 %).

Conclusions

AEE is common, but many cases of AEE may be spontaneously cured without treatment. Although symptom development is rare, quitting smoking may be helpful as a prevention strategy.

Clinical Trial Registration Number

KCT0001716.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition that develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications [1, 2]. Recent studies suggest that the prevalence of GERD is increasing and estimate that 20–40 % of patients in Western countries and 5–17 % in Asian countries are diagnosed with reflux [2–5].

There is an incomplete correspondence between reflux symptoms and endoscopic features [6–8]. It appears that the relationship between endoscopically diagnosed erosive esophagitis and the patient’s symptoms is not causal. Previous studies have shown that about two-thirds of patients who were found to have esophagitis did not have reflux symptoms [6, 8–10]. This condition is officially known as “asymptomatic erosive esophagitis (AEE)” [7, 8].

Previous studies showed that screening endoscopy could reduce the incidence of death from gastrointestinal cancer, and it is now widely performed in many countries for early detection of cancer [11, 12]. As the population that undergoes regular medical checkup increases, AEE is found during screening endoscopic examinations in a considerable number of examinees. Hence, AEE is relatively common these days. However, the natural history and clinical significance of AEE are still unclear [6, 7]. Old age, male sex, hiatal hernia, and negativity for Helicobacter pylori infection are known as predisposing factors for AEE, though some studies have produced conflicting results [6, 8, 9, 13–18].

Erosive esophagitis can provoke esophageal complications, including sentinel polyp, stricture, Barrett’s esophagus, and adenocarcinoma [10, 19]. Therefore, determining whether to treat AEE or to perform follow-up endoscopy is an important and unsolved issue [7].

We investigated the prevalence of AEE during routine health inspections and identified its predisposing factors. In addition, to determine the clinical course and significance of AEE, we examined the change in endoscopic findings and reflux symptoms over time, based on clinical follow-up results.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This study was based on data from consecutive patients who had two or more regular health inspections, including upper endoscopy, a self-reporting questionnaire, and a serum H. pylori IgG antibody test, at the Konkuk University Medical Center from January 2010 to June 2014. Subjects with an interval between health examinations of less than a year were excluded from the study. Proton pump inhibitor or histamine 2 receptor antagonist users, subjects already diagnosed with GERD, subjects under the age of 17, subjects who underwent upper GI surgery, and subjects who did not properly answer the questionnaires were also excluded. The subjects diagnosed with AEE at least once were classified into the AEE group (Fig. 1). With the exception of subjects with symptomatic erosive esophagitis or non-erosive reflux disease, all others were classified into the control group.

Study flow of the subjects. The 3300 examinees who underwent a health inspection (gastroscopy, questionnaires, and serum H. pylori IgG antibody test) more than two times at our center were investigated. When the interval of health examination was less than a year, they were excluded from the study. Proton pump inhibitor or histamine 2 receptor antagonist users, subjects already diagnosed with GERD, subjects under the age of 17, subjects who underwent upper GI surgery, and subjects who did not properly answer the questionnaires were also excluded. The subjects diagnosed with AEE at least once were classified into the AEE group. With the exception of subjects with symptomatic erosive esophagitis or non-erosive reflux disease, all other subjects were classified into the control group. The AEE follow-up group was defined as those subjects whose follow-up interval after the diagnosis of AEE was more than a year and was subdivided into groups A and B. If the reflux symptom developed more than once, the subjects belonged to group A. If the subjects had no reflux symptoms during follow-up, they belonged to group B. Seven erosive esophagitis (23.3 %) cases from group A and 167 erosive esophagitis (47.4 %) from group B disappeared at the final follow-up endoscopy

In our health care center, people underwent a health inspection at their own charge, and they could decide when to receive the medical checkup. Hence, their follow-up intervals were varied. In addition, in many cases, regular upper endoscopy was recommended regardless of their GI symptoms, in consideration of high prevalence of stomach cancer in Korea.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Konkuk University School of Medicine, which confirmed that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki (KUH1010716). This study was registered in the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS) ID: KCT0001716.

Questionnaires and Typical Reflux Symptoms

All examinees filled out a self-reporting questionnaire including typical reflux symptoms, previous medical history, underlying disease, smoking, alcohol intake, and medication history. We surveyed the drugs taken for more than a week within the past month to identify the medication history. By reviewing the medical records, we additionally reviewed the subjects’ age, gender, height, and weight. Informed consent for the use of the medical information was contained in the questionnaire.

Typical reflux symptoms were defined as acid regurgitation or heartburn at least once a week for the last 3 months. Acid regurgitation was defined as a perception of refluxed gastric contents in the mouth or hypopharynx, and heartburn was defined as having burning or hot sensation in the substernal area [1].

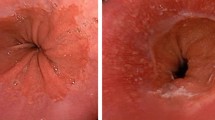

Definition of Asymptomatic Erosive Esophagitis and Esophageal Complications

All examinees provided written consent to undergo the endoscopic procedures, which were conducted using a standard upper endoscope (GF-260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan/EPK-i; Pentax, Tokyo, Japan). A diagnosis of erosive esophagitis was made in cases with hyperemic streaks or mucosal breaks on the lower esophagus. The severity of erosive esophagitis was graded from A to D according to the Los Angeles (LA) classification [20]. Minimal changes in esophageal lesions were not considered relevant in our study. AEE was defined as erosive esophagitis on endoscopy without the typical reflux symptoms [6–8].

Esophageal complications of AEE included sentinel polyp, stricture, Barrett’s esophagus, and adenocarcinoma [1]. An esophageal stricture was defined as a luminal narrowing of the esophagus caused by erosive esophagitis. Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma were confirmed by biopsy results.

Helicobacter pylori Infection Status

The presence of H. pylori infection was determined by the H. pylori IgG antibody test performed using ELISA (PlateliaTM H. pylori ELISA; Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France or CHORUS H. pylori IgG, DIESSE Diagnostica Senese, Monteriggioni, Italy). If the result of the test showed “equivocal,” it was regarded as “negative.”

Clinical Follow-Up of Asymptomatic Erosive Esophagitis

The clinical progress of AEE subjects who underwent follow-up study was investigated to evaluate the clinical characteristics and significance of AEE. Among the subjects in the AEE group, we excluded all subjects who did not undergo health inspection after the diagnosis of AEE. In addition, subjects with a follow-up interval after the diagnosis of AEE of less than a year were also excluded. After the exclusions, the remaining subjects were classified into the AEE follow-up group (Fig. 1). The AEE follow-up group was subdivided into group A and group B, according to whether or not reflux symptoms developed during follow-up. If the reflux symptom developed more than once, the subjects were assigned to group A, while subjects having no reflux symptoms during follow-up were assigned to group B.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by the Student’s t test and the Mann–Whitney test. Categorical variables were presented as number (%) and analyzed by the χ 2 test and the Fisher’s exact test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence interval (CI) for factors that are independently associated with AEE. In addition, univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the OR and 95 % CI for factor associated with symptom development of AEE. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of Subjects with Asymptomatic Erosive Esophagitis

Among the 3300 subjects visiting our center, 339 subjects were excluded from the study, for the reasons described in the Methods section. Finally, 568 subjects (19.2 %) were assigned to the AEE group and 2393 to the control group (Table 1). Four hundred fifty-five subjects (80.1 %) of the AEE group and 1518 subjects (63.4 %) of the control group were males. The mean age and body mass index (BMI) of the AEE group were 50.21 ± 10.03 (range 24–83) years and 24.96 ± 3.30 (range 16.52–39.90) kg/m2, and those of the control group were 47.67 ± 11.98 (range 20–93) years and 23.94 ± 3.10 (range 15.47–43.55) kg/m2, respectively.

Predisposing Factors for Asymptomatic Erosive Esophagitis

Subjects with AEE were older (p = 0.030), predominantly male (p < 0.001), had a higher BMI (p < 0.001), were smokers, had higher alcohol consumption (p < 0.001), lower rate of H. pylori infection (p < 0.001), and more likely to have a hiatal hernia (p = 0.012) than the control group (Table 1). Multivariate analyses revealed that age over 50 years [OR 1.285 (95 % CI 1.041–1.586), p = 0.020], male sex [OR 1.993 (95 % CI 1.521–2.610), p < 0.001], a BMI over 25 [OR 1.551 (95 % CI 1.254–1.918), p < 0.001], current smoking [OR 1.366 (95 % CI 1.068–1.748), p = 0.013], heavy drinking [OR 1.860 (95 % CI 1.244–2.781), p = 0.003], the absence of H. pylori infection [OR 2.597 (95 % CI 2.103–3.206), p < 0.001], and hiatal hernia [OR 3.062 (95 % CI 1.065–8.801), p = 0.038] were independent predisposing factors for AEE (Table 2).

Asymptomatic Erosive Esophagitis Follow-Up Group

Among the 568 subjects with AEE, 382 belonged to the AEE follow-up group. The mean frequency of health checkups was 2.42 ± 0.75, and the mean follow-up period was 25 months ± 9.5 months (Supplementary Table 1). The LA classification on initial endoscopy was A in 306 subjects (80.1 %), B in 75 (19.6 %), and C in 1 (0.3 %). Complications related to reflux were observed in 5 subjects (3 with Barrett’s esophagus and 2 with sentinel polyp) on initial endoscopy, and 2 complications (1 Barrett’s esophagus and 1 sentinel polyp) showed onset during the follow-up period (Table 3). All cases of Barrett’s esophagus were classified as short segment.

Reflux symptoms developed in 30 subjects (group A, 7.9 %) within the follow-up period, while there was no symptom development in the remaining 352 subjects (group B, 92.1 %). Only one subject of group A was taking an acid suppression medication for the reflux symptom at the time of the follow-up inspection. In group B, no one was being treated with acid suppression medication. Seven patients (23.3 %) from group A did not show signs of erosive esophagitis on the follow-up endoscopy, and none was recurrent. One hundred and sixty-seven patients (47.4 %) from group B did not show signs of erosive esophagitis at the final follow-up endoscopy. Erosive esophagitis on final endoscopy was more common in group A (n = 23, 76.7 %) than in group B (n = 185, 52.6 %) (p = 0.012). In addition, smokers were more common in group A (n = 14, 50 %) than in group B (n = 86, 27.5 %) (p = 0.017). There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, BMI, alcohol consumption, H. pylori infection, hiatal hernia, diabetes, LA classification, or complications between the two groups. Logistic regression analysis showed that current smoking [OR 2.640 (95 % CI 1.208–5.765), p = 0.015] was a risk factor for symptom development of AEE.

Discussion

Our results show that AEE is commonly identified during screening endoscopic examinations. The number of subjects diagnosed with AEE during the study period was 568 (19.2 %). Hence, it is important to determine whether treatment and surveillance for patients with AEE should be conducted or not. To date, there have been substantial practice variations in the treatment of AEE [6, 7]. But in general, aggressive treatment for AEE is not recommended. Therapeutic compliance of AEE patients is poor because there are no symptoms. In addition, there is no evidence that medical treatment prevents the development of symptoms or complications. In our study, many AEE spontaneously disappeared on follow-up endoscopy and reflux symptoms developed in only 7.9 % during the follow-up period. Therefore, in most instances, treatment does not seem to be necessary.

Because AEE patients have no symptoms, they would not seek medical help. However, they are still at risk of developing GERD complications, such as Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma [10, 19]. Therefore, these patients are an easily overlooked, but clinically important population. In our study, there were no cases of new onset esophageal cancer or stricture. Only one case of Barrett’s esophagus and one case of sentinel polyp had onset during the follow-up period. However, the follow-up period was too short to develop these complications. Nearly half of the patients with esophagitis were spontaneously cured without treatment as evidenced by follow-up endoscopy. However, the remaining subjects still had an AEE on the follow-up study, and they may represent those who need to undergo clinical follow-up and endoscopic surveillance. To determine whether some of these patients ultimately develop complications, long-term follow-up studies are needed.

Older age, male sex, family history of GERD, higher socioeconomic status, increased BMI, heavy drinking, and smoking are known risk factors for GERD [2, 4, 19, 21]. In addition, several previous studies have shown that H. pylori infection has a protective effect on GERD as a consequence of gastric atrophy and hypochlorhydria induced by parietal cell destruction, although sometimes conflicting data have been published [22, 23]. Our results revealed that age over 50 years, male sex, a BMI over 25, current smoking, heavy drinking, negativity for H. pylori infection, and hiatal hernia are independent predisposing factors for AEE. These results show that the risk factors for AEE are similar to the risk factors for GERD. Therefore, pathogenesis of the two diseases would be the same.

In our study, smoking was the only risk factor for the development of symptoms in patients with AEE. A previous study revealed that smoking was related with overlaps among GERD, irritable bowel syndrome, and functional dyspepsia [4]. In addition, smoking has also been associated with the presence of reflux esophagitis in men [21]. Smoking can decrease lower esophageal sphincter pressure, increase acid and pepsinogen secretion in stomach, and delay gastric emptying [24–26]. Therefore, persistent smoking after a diagnosis of AEE can promote the development of symptoms. For the same reasons, stopping smoking may be helpful in preventing the development of symptoms in AEE patients.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, as noted above, the follow-up period of the study was short. Secondly, extra-esophageal symptoms, such as chronic cough and hoarseness, were not surveyed in our study. However, the symptoms have limited evidence of causality with reflux [1, 2, 27]. Thirdly, there is subjectivity involved in LA classification, which is sometimes difficult to classify. Therefore, spontaneous healing of esophagitis can be just due to inter-observer variability. Fourthly, the H. pylori IgG antibody test cannot distinguish the current infection from the past infection. However, other H. pylori tests, such as biopsy stained with Giemsa, urea breath test, and rapid urease test, were done only in limited cases. In practice, it is very difficult to carry out the tests as a screening test. Fifthly, at the time of the health inspection, we surveyed the drugs taken within the past month to identify the medication history. Therefore, we could not figure out whether the subjects took an antacid medication during the rest of the follow-up period. Sixthly, we used a narrow definition of typical reflux symptoms in terms of the duration of symptoms. This definition may have classified some patients with symptomatic erosive esophagitis as AEE patient. Lastly, there were some missing values: The BMI of 13 subjects was not measured or was not recorded.

In conclusion, AEE is commonly found during endoscopic screening examinations, and nearly half of patients with AEE may not show signs of erosive esophagitis on the follow-up endoscopy. Age over 50 years, male sex, a BMI over 25, current smokers, heavy drinkers, negativity for H. pylori infection, and hiatal hernia are independent predisposing factors. Development of reflux symptoms over a period of a few years is rare, and smoking is the only risk factor for the development of AEE symptoms.

Abbreviations

- AEE:

-

Asymptomatic erosive esophagitis

- GERD:

-

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

References

Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R, Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920.

Fock KM, Talley NJ, Fass R, et al. Asia-pacific consensus on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: update. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:8–22.

El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63:871–880.

Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:518–534.

Goh KL, Chang CS, Fock KM, Ke M, Park HJ, Lam SK. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:230–238.

Choi JY, Jung HK, Song EM, Shim KN, Jung SA. Determinants of symptoms in gastroesophageal reflux disease: nonerosive reflux disease, symptomatic, and silent erosive reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:764–771.

Lim SW, Lee JH, Kim JH, Kim JH, Kim HU, Jeon SW. Management of asymptomatic erosive esophagitis: an E-mail survey of physician’s opinions. Gut Liver. 2013;7:290–294.

Lee D, Lee KJ, Kim KM, Lim SK. Prevalence of asymptomatic erosive esophagitis and factors associated with symptom presentation of erosive esophagitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:906–912.

Li CH, Hsieh TC, Hsiao TH, et al. Different risk factors between reflux symptoms and mucosal injury in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2015;31:320–327.

Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Storskrubb T, et al. Erosive esophagitis is a risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus: a community-based endoscopic follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1946–1952.

Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687–696.

Dan YY, So JB, Yeoh KG. Endoscopic screening for gastric cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:709–716.

Wang PC, Hsu CS, Tseng TC, et al. Male sex, hiatus hernia, and Helicobacter pylori infection associated with asymptomatic erosive esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:586–591.

Cho JH, Kim HM, Ko GJ, et al. Old age and male sex are associated with increased risk of asymptomatic erosive esophagitis: analysis of data from local health examinations by the Korean national health insurance corporation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1034–1038.

Lei WY, Yu HC, Wen SH, et al. Predictive factors of silent reflux in subjects with erosive esophagitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:24–29.

Jung SH, Oh JH, Kang SG. Clinical characteristics and natural history of asymptomatic erosive esophagitis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014;25:248–252.

Akyuz F, Uyanikoglu A, Ermis F, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in asymptomatic obese subjects: an esophageal impedance-pH study. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3030–3034.

Nagahara A, Hojo M, Asaoka D, et al. Clinical feature of asymptomatic reflux esophagitis in patients who underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:53–57.

Boeckxstaens G, El-Serag HB, Smout AJ, Kahrilas PJ. Symptomatic reflux disease: the present, the past and the future. Gut. 2014;63:1185–1193.

Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–180.

Matsuzaki J, Suzuki H, Kobayakawa M, et al. Association of visceral fat area, smoking, and alcohol consumption with reflux esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in Japan. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133865.

Sharma P, Vakil N. Review article: Helicobacter pylori and reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:297–305.

Haruma K. Review article: influence of Helicobacter pylori on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:40–44.

Thomas GA, Rhodes J, Ingram JR. Mechanisms of disease: nicotine—a review of its actions in the context of gastrointestinal disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:536–544.

Dodds WJ, Dent J, Hogan WJ, et al. Mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1547–1552.

Miller G, Palmer KR, Smith B, Ferrington C, Merrick MV. Smoking delays gastric emptying of solids. Gut. 1989;30:50–53.

Tomita T, Yasuda T, Oka H, et al. Atypical symptoms and health-related quality of life of patients with asymptomatic reflux esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:19–24.

Authors’ contributions

SPL involved in study concept, designed and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript; IKS was responsible for study concept, interpreted, and drafted the manuscript; JHK, SYL, HSP, and CSS involved in acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Konkuk University Medical Center (KUH1010716).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S.P., Sung, IK., Kim, J.H. et al. The Clinical Features and Predisposing Factors of Asymptomatic Erosive Esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 61, 3522–3529 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-016-4341-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-016-4341-9