Abstract

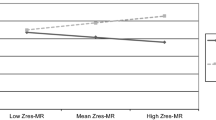

We used PDA devices and an experience sampling technique to assess participants’ negative mood and thoughts as they engaged in their normal daily routines over the course of a week. We then calculated each person’s own unique relationship between mood and thoughts, and used this index of cognitive reactivity to predict depressive symptoms at 6-month follow-up. Participants who demonstrated a stronger link between their momentary negative mood and negative cognitions reported more depressive symptoms at follow-up than those who had a weaker relationship between mood and cognitions. Further, this cognitive reactivity index was a better predictor of follow-up depressive symptom scores than initial depressive symptoms, dysfunctional attitudes, average experienced negative mood or thoughts, or variability of negative mood or thoughts. These results are consistent with earlier findings and build on previous research by demonstrating that naturally occurring cognitive reactivity is predictive of future mood disruptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The current study sample was comprised of undergraduate students, and most participants were likely not clinically depressed. We therefore use the terms “symptoms of depression” and “depressive symptomatology” (rather than “depression”) to refer to our outcome variable of interest. We used the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Questionnaire to assess depressive symptomatology in the current study. This scale was designed specifically to assess symptoms of depression in community samples.

Ten (9%) of our initial sample of 112 participants did not complete a minimum of 14 momentary assessments (range = 1–13). These participants’ data were excluded from analyses and their study participation ended after the weeklong momentary assessment phase (i.e., they were not contacted for and did not participate in the follow-up study procedures).

Sex was not a significant moderator of any of the reported associations (P > .05).

References

Abela, J. R. Z., & D’Alessandro, D. U. (2002). Beck’s cognitive theory of depression: A test of the diathesis-stress and causal mediation components. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 41, 111–128.

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Beck, A. T., Brown, G., Steer, R. A., Eidelson, J. I., & Riskind, J. H. (1987). Differentiating anxiety and depression: A test of the cognitive content-specificity hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96, 179–183.

Dobson, K. S., & Breiter, H. J. (1983). Cognitive assessment of depression: Reliability and validity of three measures. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 92, 107–109.

Dykman, B. M., & Johll, M. (1998). Dysfunctional attitudes and vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A 14-week longitudinal study. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 337–352.

Fichman, L., Koestner, R., Zuroff, D. C., & Gordon, L. (1999). Depressive styles and the regulation of negative affect: A daily experience study. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 23, 483–495.

Gemar, M. C., Segal, Z. V., Sagrati, S., & Kennedy, S. J. (2001). Mood-induced changes on the implicit association test in recovered depressed patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 282–289.

Gotlib, I. H., & Cane, D. B. (1987). Construct accessibility and clinical depression: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96, 199–204.

Gotlib, I. H., Joormann, J., Minor, K. L., & Hallmayer, J. (2008). HPA axis reactivity: A mechanism underlying the associations among 5-HTTLPR, stress, and depression. Biological Psychiatry, 63, 847–851.

Gunthert, K. C., Cohen, L. H., & Armeli, S. (2002). Unique effects of depressive and anxious symptomatology on daily stress and coping. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 21, 583–609.

Hankin, B. L., Abramson, L. Y., Miller, N., & Haeffel, G. J. (2004). Cognitive vulnerability-stress theories of depression: Examining affective specificity in the prediction of depression versus anxiety in three prospective studies. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28, 309–345.

Hollon, S. D., & Kendall, P. C. (1980). Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 4, 383–395.

Ingram, R. E., & Wisnicki, K. S. (1988). Assessment of automatic positive cognition. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 898–902.

Just, N., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2001). Remitted depression studies as tests of the cognitive vulnerability hypotheses of depression onset: A critique and conceptual analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 63–83.

Kuiper, N. A., Olinger, L. J., & Air, P. J. (1985). Stress, coping, and vulnerability to depression. Unpublished manuscript, University of Western Ontario.

Kwon, S., & Oei, T. P. S. (1992). Differential causal roles of dysfunctional attitudes and automatic thoughts in depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 16, 309–328.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Steinmetz, J., Larson, D., & Franklin, J. (1981). Depression related cognitions: Antecedents or consequences? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90, 213–219.

Miranda, J., Gross, J. J., Persons, J. B., & Hahn, J. (1998). Mood matters: Negative mood induction activates dysfunctional attitudes in women vulnerable to depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 363–376.

Miranda, J., & Persons, J. B. (1988). Dysfunctional attitudes are mood-state dependent. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 76–79.

Myin-Germeys, I., Peeters, F., Havermans, R., Nicolson, N. A., deVries, M. W., Delespaul, P., et al. (2003). Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis and affective disorder: An experience sampling study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 107, 124–131.

O’Neill, S. C., Cohen, L. H., Tolpin, L. H., & Gunthert, K. C. (2004). Affective reactivity to daily interpersonal stressors as a prospective predictor of depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 172–194.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Riley, W. T., Treiber, F. A., & Woods, M. G. (1989). Anger and hostility in depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 177, 668–674.

Roberts, J. E., & Kassel, J. D. (1996). Mood state dependence in cognitive vulnerability to depression: The roles of positive and negative affect. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 20, 1–12.

Sanderson, W. C., DiNardo, P. A., Rapee, R. M., & Barlow, D. H. (1990). Syndrome comorbidity in patients diagnosed with a DSM-III-R anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 308–312.

Sandler, I., & Lakey, B. (1982). Locus of control as a stress moderator: The role of control perceptions and social support. American Journal of Community Psychology, 10, 65–78.

Scher, C. D., Ingram, R. E., & Segal, Z. V. (2005). Cognitive reactivity and vulnerability: Empirical evaluation of construct activation and cognitive diatheses in unipolar depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 487–510.

Segal, Z. V., Gemar, M., & Williams, S. (1999). Differential cognitive response to a mood challenge following successful cognitive therapy or pharmacotherapy for unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 3–10.

Segal, Z. V., Kennedy, S., Gemar, M., Hood, K., Pederson, R., & Buis, T. (2006). Cognitive reactivity to sad mood provocation and the prediction of depressive relapse. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 749–755.

Snyder, C. R., Crowson, J. J., Houston, B. K., Kurylo, M., & Poirier, J. (1997). Assessing hostile automatic thoughts: Development and validation of the HAT scale. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 21, 477–492.

Stone, A., & Shiffman, S. (1994). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 16, 199–202.

Tennen, H., Affleck, G., & Zautra, A. (2006). Depression history and coping with chronic pain: A daily process analysis. Health Psychology, 25, 370–379.

Van der Does, W. (2002). Cognitive reactivity to sad mood: Structure and validity of a new measure. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 105–120.

Watson, D. & Clark, L. A. (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule—expanded form. Unpublished Manuscript. Iowa City: University of Iowa.

Weissman, A. (1980). Assessing depressogenic attitudes: A validation study. Paper presented at the 51st annual meeting of the Eastern Psychological Association, Hartford, CT.

Weissman, A., & Beck, A. T. (1978). Development and validation of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale: A preliminary investigation. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Education Research Association, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Wenze, S. J., Gunthert, K. C., & Forand, N. R. (2007). Influence of dysphoria on positive and negative cognitive reactivity to daily mood fluctuations. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 915–927.

Wenze, S. J., Gunthert, K. C., Forand, N. R., & Laurenceau, J. P. (2009). The influence of dysphoria on reactivity to naturalistic fluctuations in anger. Journal of Personality, 77, 795–824.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wenze, S.J., Gunthert, K.C. & Forand, N.R. Cognitive Reactivity in Everyday Life as a Prospective Predictor of Depressive Symptoms. Cogn Ther Res 34, 554–562 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-010-9299-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-010-9299-x