Abstract

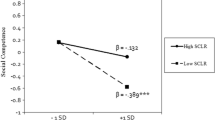

Both social support and social stress can impact adolescent physiology including hormonal responses during the sensitive transition to adolescence. Social support from parents continues to play an important role in socioemotional development during adolescence. Sources of social support and stress may be particularly impactful for adolescents with social anxiety symptoms. The goal of the current study was to examine whether adolescent social anxiety symptoms and maternal comfort moderated adolescents’ hormonal response to social stress and support. We evaluated 47 emotionally healthy 11- to 14-year-old adolescents’ cortisol and oxytocin reactivity to social stress and support using a modified version of the Trier Social Stress Test for Adolescents that included a maternal comfort paradigm. Findings demonstrated that adolescents showed significant increases in cortisol and significant decreases in oxytocin following the social stress task. Subsequently, we found that adolescents showed significant decreases in cortisol and increases in oxytocin following the maternal comfort paradigm. Adolescents with greater social anxiety symptoms showed higher levels of cortisol at baseline but greater declines in cortisol response following maternal social support. Social anxiety symptoms were unrelated to oxytocin response to social stress or support. Our findings provide further evidence that mothers play a key role in adolescent regulation of physiological response, particularly if the stressor is consistent with adolescents’ anxiety. More specifically, our findings suggest that adolescents with higher social anxiety symptoms show greater sensitivity to maternal social support following social stressors. Encouraging parents to continue to serve as a supportive presence during adolescent distress may be helpful for promoting stress recovery during the vulnerable transition to adolescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data is available upon request.

Notes

6 participants had 3 judges present in the room instead of one present in the room (and two judges watching via camera). We chose to change this procedure to increase feasibility of data collection due to staffing needs. There were no significant differences in these 6 adolescents compared to the remaining 41 adolescents in terms of cortisol or oxytocin at any time point (ps = 0.09–0.94) or for adolescent social anxiety symptoms or maternal comforting behaviors (ps = 0.18–0.67).

References

Dahl RE (2004) Adolescent brain development: a period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Keynote Address. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1021(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1308.001

Spear L (2000) The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 24(4):417–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2

Crone EA, Dahl RE (2012) Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat Rev Neurosci 13:636–650

Weems CF, Costa NM (2005) Developmental differences in the expression of childhood anxiety symptoms and fears. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44(7):656–663

Westenberg PM, Gullone E, Bokhorst CL, Heyne DA, King NJ (2007) Social evaluation fear in childhood and adolescence: normative developmental course and continuity of individual differences. Br J Dev Psychol 25(3):471–483

Dahl RE, Gunnar MR (2009) Heightened stress responsiveness and emotional reactivity during pubertal maturation: implications for psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 21(1):1–6

Sumter SR, Bokhorst CL, Miers AC, Van Pelt J, Westenberg PM (2010) Age and puberty differences in stress responses during a public speaking task: do adolescents grow more sensitive to social evaluation? Psychoneuroendocrinology 35(10):1510–1516

Ollendick TH, Hirshfeld-Becker DR (2002) The developmental psychopathology of social anxiety disorder. Biol Psychiat 51:449–458

Ernst M, Romeo RD, Andersen SL (2009) Neurobiology of the development of motivated behaviors in adolescence: a window into a neural systems model. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 93(3):199–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2008.12.013

Hostinar CE, Sullivan RM, Gunnar MR (2014) Psychobiological mechanisms underlying the social buffering of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis: a review of animal models and human studies across development. Psychol Bull 140(1):256–282. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032671

Gunnar MR, Donzella B (2002) Social regulation of the cortisol levels in early human development. Psychoneuroendocrinology 27(1–2):199–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00045-2

Seltzer LJ, Ziegler TE, Pollak SD (2010) Social vocalizations can release oxytocin in humans. Proc R Soc B 277(1694):2661–2666. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.0567

Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR (2007) The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Soc Dev 16(2):361–388

Laursen B, Collins WA (2009) Parent-child relationships during adolescence. Handb Adolesc Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy002002

Shamay-Tsoory SG, Abu-Akel A (2016) The social salience hypothesis of oxytocin. Biol Psychiat 79(3):194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.07.020

Doom JR, Hostinar CE, VanZomeren-Dohn AA, Gunnar MR (2015) The roles of puberty and age in explaining the diminished effectiveness of parental buffering of HPA reactivity and recovery in adolescence. Psychoneuroendocrinology 59:102–111

Hostinar CE, Johnson AE, Gunnar MR (2015) Parent support is less effective in buffering cortisol stress reactivity for adolescents compared to children. Dev Sci 18:281–297

Parenteau AM, Alen NV, Deer LK, Nissen AT, Luck AT, Hostinar CE (2020) Parenting matters: parents can reduce or amplify children’s anxiety and cortisol responses to acute stress. Dev Psychopathol 32:1799–1809

Zorn JV, Schür RR, Boks MP, Kahn RS, Joëls M, Vinkers CH (2017) Cortisol stress reactivity across psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 77:25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.11.036

Bernhard A, Van der Merwe C, Ackermann K, Martinelli A, Neumann ID, Freitag CM (2018) Adolescent oxytocin response to stress and its behavioral and endocrine correlates. Horm Behav 105:157–165

Gunnar MR, Wewerka S, Frenn K, Long JD, Griggs C (2009) Developmental changes in hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal activity over the transition to adolescence: normative changes and associations with puberty. Dev Psychopathol 21(1):69–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579409000054

Gunnar M, Quevedo K (2007) The neurobiology of stress and development. Annu Rev Psychol 58(1):145–173. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605

Feldman R, Gordon I, Influs M, Gutbir T, Ebstein RP (2013) Parental oxytocin and early caregiving jointly shape children’s oxytocin response and social reciprocity. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:1154–1162

Shamay-Tsoory S, Young LJ (2016) Understanding the oxytocin system and its relevance to psychiatry. Biol Psychiat 79(3):150–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.10.014

Neurman ID, Slattery DA (2016) Oxytocin in general anxiety and social fear: a translational approach. Biol Psychiat 79:213–221

Heinrichs M, Baumgartner T, Kirschbaum C, Ehlert U (2003) Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biol Psychiat 54:1389–1398

Shortt JW, Stoolmiller M, Smith-Shine JN, Mark Eddy J, Sheeber L (2010) Maternal emotion coaching, adolescent anger regulation, and siblings’ externalizing symptoms. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51(7):799–808

O’Neal CR, Magai C (2005) Do parents respond in different ways when children feel different emotions? The emotional context of parenting. Dev Psychopathol 17:467–487

Stocker CM, Richmond MK, Rhoades GK, Kiang L (2007) Family emotional processes and adolescents’ adjustment. Soc Dev 16:310–325

Buckholdt KE, Parra GR, Jobe-Shields L (2014) Intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation through parental invalidation of emotions: implications for adolescent internalizing and externalizing behaviors. J Child Fam Stud 23:324–332

Knappe S, Sasagawa S, Creswell C (2015) Developmental epidemiology of social anxiety and social phobia in adolescents. Social anxiety and phobia in adolescent: Development, manifestation, and intervention strategies, 39–70

Wittchen H, Stein M, Kessler R (1999) Social fears and social phobia in a community sample of adolescents and ySpoung adults: prevalence, risk factors and co-morbidity. Psychol Med 29(2):309–323. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291798008174

Walker EF, Walder DJ, Reynolds F (2001) Developmental changes in cortisol secretion in normal and at-risk youth. Dev Psychopathol 13(3):721–732. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579401003169

Morgan JK, Lee GE, Wright AG, Gilchrist DE, Forbes EE, McMakin DL, Dahl RE, Ladouceur CD, Ryan ND, Silk JS (2017) Altered positive affect in clinically anxious youth: the role of social context and anxiety subtype. J Abnorm Child Psychol 45:1461–1472

Nelson EE, Jarcho JM, Guyer AE (2016) Social re-orientation and brain development: an expanded and updated view. Dev Cogn Neurosci 17:118–127

Klimes-Dougan B, Brand AE, Zahn-Waxler C, Usher B, Hastings PD, Kendziora K, Garside RB (2007) Parental emotion socialization in adolescence: differences in sex, age, and problem status. Soc Dev 16:326–342

Hoyt LT, Craske MG, Mineka S, Adam EK (2015) Positive and negative affect and arousal: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with adolescent cortisol diurnal rhythms. Psychosom Med 77:392

Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, Cully M, Balach L, Kaufman J, Neer SM (1997) The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:545–553

Grewen KM, Davenport RE, Light KC (2010) An investigation of plasma and salivary oxytocin responses in breast- and formula-feeding mothers of infants. Psychophysiology 47:625–632

Yim I, Quas JA, Cahill L, Hayakawa CM (2010) Children’s and adults’ salivary cortisol responses to an identical psychosocial laboratory stressor. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35:241–248

Liu JJ, Ein N, Peck K, Huang V, Pruessner JC, Vickers K (2017) Sex differences in salivary cortisol reactivity to the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST): a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 82:26–37

Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH (1993) The “Trier Social Stress Test”—a tool for investigating psychobiologal stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28:76–81

Porter LS, Mishel M, Neelon V, Belyea M, Pisano E, Soo MS (2003) Cortisol levels and responses to mammography screening in breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. Psychosom Med 65:842–848

Izard CE, Dougherty LM, Hembree EA (1983) A system for affect expression identification by holistic judgments (AFFEX). University of Delaware, Instructional Resources Center, p 1983

Morgan JK, Silk JS, Olino TM, Forbes EE (2020) Depression moderates maternal response to preschoolers’ positive affect. Infant Child Dev 29

Schludermann S, Schludermann E (1988) Questionnaire for children and youth (CRPBI-30). Unpublished manuscript, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg

Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M (1999) Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:1230–1236

Gunnar MR, Hostinar CE (2015) The social buffering of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans: developmental and experiential determinants. Soc Neurosci 10:479–485

Cougle JR, Fitch KE, Fincham FD, Riccardi CJ, Keough ME, Timpano KR (2012) Excessive reassurance seeking and anxiety pathology: Tests of incremental associations and directionality. J Anxiety Disord 26:117–125

Oppenheimer CW, Technow JR, Hankin BL, Young JF, Abela JR (2012) Rumination and excessive reassurance seeking: investigation of the vulnerability model and specificity to depression. Int J Cogn Ther 5:254–267

Gar NS, Hudson JL (2009) The association between maternal anxiety and treatment outcome for childhood anxiety disorders. Behav Change 26:1–15

McCullough ME, Churchland PS, Mendez AJ (2013) Problems with measuring peripheral oxytocin: can the data on oxytocin and human behavior be trusted? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 37:1485–1492

Miers AC (2021) An investigation into the influence of positive peer feedback on self-relevant cognitions in social anxiety. Behav Change 38:193–207

Seddon JA, Rodriguez VJ, Provencher Y, Raftery-Helmer J, Hersh J, Labelle PR, Thomassin K (2020) Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of the Trier Social Stress Test in eliciting physiological stress responses in children and adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology 116:104582

Acknowledgements

We thank the families and staff of the Families, Affect, and the Brain study at the University of Pittsburgh for their time and commitment to this research. Correspondence to Judith K. Morgan, PhD at morganjk@upmc.edu.

Funding

This work was supported by the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation (PI: Judith K. Morgan).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JM conceived of the study, led its design and coordination, participated in analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafted and finalized the manuscript. KC and RF participated in interpretation of the data and drafting the manuscript. TO and SI led analysis and interpretation of the data. KG helped conceive of the study, participated in its design, and led processing of saliva samples. JS, JC, and EF helped conceive of the study and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Morgan, J.K., Conner, K.K., Fridley, R.M. et al. Adolescents’ Hormonal Responses to Social Stress and Associations with Adolescent Social Anxiety and Maternal Comfort: A Preliminary Study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01521-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01521-0