Abstract

Objective

Utilizing data from the largest study to date, we examined associations between maternal preconception/prenatal exposure to household chemicals and infant acute leukemia.

Methods

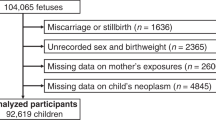

We present data from a Children’s Oncology Group case–control study of 443 infants (<1 year of age) diagnosed with acute leukemia [including acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML)] between 1996 and 2006 and 324 population controls. Mothers recalled household chemical use 1 month before and throughout pregnancy. We used unconditional logistic regression adjusted for birth year, maternal age, and race/ethnicity to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

We did not find evidence for an association between infant leukemia and eight of nine chemical categories. However, exposure to petroleum products during pregnancy was associated with AML (OR = 2.54; 95% CI:1.40–4.62) and leukemia without mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) gene rearrangements (“MLL−”) (OR = 2.69; 95% CI: 1.47–4.93). No associations were observed for exposure in the month before pregnancy.

Conclusions

Gestational exposure to petroleum products was associated with infant leukemia, particularly AML, and MLL− cases. Benzene is implicated as a potential carcinogen within this exposure category, but a clear biological mechanism has yet to be elucidated.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Linabery AM, Ross JA (2008) Trends in childhood cancer incidence in the US (1992–2004). Cancer 112:416–432

Linabery AM, Ross JA (2008) Childhood and adolescent cancer survival in the US by race and ethnicity for the diagnostic period 1975–1999. Cancer 113:2575–2596

Ross JA (2000) Dietary flavonoids and the MLL gene: a pathway to infant leukemia? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:4411–4413

Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA (2007) MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat Rev Cancer 7:823–833

Eden T (2010) Aetiology of childhood leukaemia. Cancer Treat Rev 36:286–297

Stam RW, Schneider P, Hagelstein JA, van der Linden MH, Stumpel DJ et al (2010) Gene expression profiling-based dissection of MLL translocated and MLL germline acute lymphoblastic leukemia in infants. Blood 115:2835–2844

Chowdhury T, Brady HJ (2008) Insights from clinical studies into the role of the MLL gene in infant and childhood leukemia. Blood Cells Mol Dis 40:192–199

Greaves MF, Maia AT, Wiemels JL, Ford AM (2003) Leukemia in twins: lessons in natural history. Blood 102:2321–2333

Gale KB, Ford AM, Repp R, Borkhardt A, Keller C et al (1997) Backtracking leukemia to birth: identification of clonotypic gene fusion sequences in neonatal blood spots. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:13950–13954

Smith MT (2010) Advances in understanding benzene health effects and susceptibility. Annu Rev Public Health 31:133–148 132 p following 148

Buffler PA, Kwan ML, Reynolds P, Urayama KY (2005) Environmental and genetic risk factors for childhood leukemia: appraising the evidence. Cancer Invest 23:60–75

Turner MC, Wigle DT, Krewski D (2010) Residential pesticides and childhood leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect 118:33–41

Pombo-de-Oliveira MS, Koifman S (2006) Infant acute leukemia and maternal exposures during pregnancy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15:2336–2341

Alexander FE, Patheal SL, Biondi A, Brandalise S, Cabrera ME et al (2001) Transplacental chemical exposure and risk of infant leukemia with MLL gene fusion. Cancer Res 61:2542–2546

Puumala SE, Spector LG, Robison LL, Bunin GR, Olshan AF et al (2009) Comparability and representativeness of control groups in a case-control study of infant leukemia: a report from the children’s oncology group. Am J Epidemiol 170:379–387

Johnson KJ, Roesler MA, Linabery AM, Hilden JM, Davies SM et al (2010) Infant leukemia and congenital abnormalities: a children’s oncology group study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 55:95–99

Puumala SE, Spector LG, Wall MM, Robison LL, Heerema NA et al (2010) Infant leukemia and parental infertility or its treatment: a children’s oncology group report. Hum Reprod 25:1561–1568

Robison LL, Daigle A (1984) Control selection using random digit dialing for cases of childhood cancer. Am J Epidemiol 120:164–166

Waksberg JS (1978) Sampling methods for random digit dialing. J Am Stat Assoc 73:40–46

Spector LG, Xie Y, Robison LL, Heerema NA, Hilden JM et al (2005) Maternal diet and infant leukemia: the DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor hypothesis: a report from the children’s oncology group. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14:651–655

Armstrong SA, Staunton JE, Silverman LB, Pieters R, den Boer ML et al (2002) MLL translocations specify a distinct gene expression profile that distinguishes a unique leukemia. Nat Genet 30:41–47

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL (2008) Modern epidemiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia p. 345–380

Mondrala S, Eastmond DA (2010) Topoisomerase II inhibition by the bioactivated benzene metabolite hydroquinone involves multiple mechanisms. Chem Biol Interact 184:259–268

Schnatter AR, Rosamilia K, Wojcik NC (2005) Review of the literature on benzene exposure and leukemia subtypes. Chem Biol Interact 153–154:9–21

Pyatt D, Hays S (2010) A review of the potential association between childhood leukemia and benzene. Chem Biol Interact 184:151–164

Scelo G, Metayer C, Zhang L, Wiemels JL, Aldrich MC et al (2009) Household exposure to paint and petroleum solvents, chromosomal translocations, and the risk of childhood leukemia. Environ Health Perspect 117:133–139

Dowty BJ, Laseter JL, Storer J (1976) The transplacental migration and accumulation in blood of volatile organic constituents. Pediatr Res 10:696–701

Ross ME, Mahfouz R, Onciu M, Liu HC, Zhou X et al (2004) Gene expression profiling of pediatric acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 104:3679–3687

Corti M, Snyder CA (1998) Gender- and age-specific cytotoxic susceptibility to benzene metabolites in vitro. Toxicol Sci 41:42–48

Keller KA, Snyder CA (1986) Mice exposed in utero to low concentrations of benzene exhibit enduring changes in their colony forming hematopoietic cells. Toxicology 42:171–181

Infante-Rivard C, Weichenthal S (2007) Pesticides and childhood cancer: an update of Zahm and Ward’s 1998 review. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 10:81–99

Metayer C, Buffler PA (2008) Residential exposures to pesticides and childhood leukaemia. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 132:212–219

Lichter SR, Rothman S (1999) Environmental cancer–a political disease?, vol xiii. Yale University Press, New Haven, pp 235

Harris SA (2007) Assessment of pesticide exposure for epidemiological research: measurement error and bias. In: Krieger RI, Ragsdale NN, Seiber JN (eds) Assessing exposures and reducing risks to people from the use of pesticides. American Chemical Society; Distributed by Oxford University Press, Washington, pp 173–186

Ross JA, Severson RK, Pollock BH, Robison LL (1996) Childhood cancer in the United States. A geographical analysis of cases from the pediatric cooperative clinical trials groups. Cancer 77:201–207

Liu L, Krailo M, Reaman GH, Bernstein L (2003) Childhood cancer patients’ access to cooperative group cancer programs: a population-based study. Cancer 97:1339–1345

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Cindy K. Blair and Michelle A. Roesler for their helpful comments and suggestions. This research is funded by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA79940, T32 CA99936, U10 CA13539, and U10 CA98543, U10 CA98413, P30 CA77598 (University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center shared resource: Health Survey Research Center), and the Children’s Cancer Research Fund, Minneapolis, MN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: maternal telephone interview guide: household chemical exposure section

Appendix: maternal telephone interview guide: household chemical exposure section

Scripted question:

“Thinking about the month before your pregnancy, and during your pregnancy, did you come in contact with any of these products used in or around your house or apartment:”

Exposure category | Description from questionnaire/interview |

|---|---|

Insecticides | Products used to control household insects, such as Raid, Black Flag bug spray, Ortho Hornet and Wasp Killer, no-pest strips, ant traps, or roach baits. This would include handling the product, having it in the living areas of your home, or being close enough to smell it. |

Moth control | Products used to control moths, such as mothballs. This would include wearing or handling clothes that had been stored in mothballs. |

Rodenticides | Products used around the home to control mice, rats, gophers, or moles, such as D-Con or Warfarin. This would include handling the product, having it in the living areas of your home, or being close enough to smell it. |

Flea or tick control | Products used around your home to control fleas or ticks, such as Holiday, Four-Gone Foggers, or flea collars for pets. This would include handling the product, having it in the living areas of your home, or being close enough to smell it. |

Herbicides | Home or garden products used around the house or apartment, such as dandelion killers, crabgrass killers, slug or snail baits, or treatments for plant and tree insects or diseases. This would include handling the product, being close enough to smell it, or walking on the grass within 3 days of treatment. |

Insect repellants | Insect repellants, such as Off, Cutters, or Skintastic. (Skin contact). |

Professional pest exterminations | Your home was treated by exterminators. (Treated by professional or self). |

Paints, stains, lacquers | Paints, stains, or lacquers. This would include being in the area where paint was used or being close enough to smell the paint. (Own home only). |

Petroleum products | Petroleum products, such as gasoline, kerosene, lubricating oils, or spot removers. This would not include pumping gas, unless you got gasoline on your skin. Does not include Vaseline. (Own home only). |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Slater, M.E., Linabery, A.M., Spector, L.G. et al. Maternal exposure to household chemicals and risk of infant leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer Causes Control 22, 1197–1204 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-011-9798-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-011-9798-4