Abstract

The debate around ethical consumption is often characterised by discussion of its numerous failures arising from complexity in perceived trade-offs. In response, this paper advances a pragmatist understanding of the role and nature of trade-offs in ethical consumption. In doing so, it draws on the central roles of values and value in consumption and pragmatist philosophical thought, and proposes a critique of the ethical consumer as rational maximiser and the cognitive and utilitarian discourse of individual trade-offs to understand how sustainable consumption practices are established and maintained. An in-depth qualitative study is conducted employing phenomenological interviews and hermeneutic analysis to explore the consumption stories of a group of ethically minded consumers. The research uncovers the location of value within a fluid, yet habitual, plurality of patterns, preferences, morals, identities and relationships. Its contribution is to propose that consumer perception of value in moral judgements is represented by an overall form of aggregate personal advantage, which lacks conscious reflection and delivers a phenomenological form of value rooted in habits, reflecting a pragmatist representation of value unified as a ‘consummatory experience’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

“I’ll never know which way to flow; set a course that I don’t know”. Teenage Fanclub (1990), ‘Everything Flows’. (From A Catholic Education: Paperhouse Records).

The debate around ethical consumption is increasingly characterised by discussion of its numerous failures (Littler 2011) manifest, for example, in considerations of the attitude–behaviour gap (Carrington et al. 2014, 2010; Johnstone and Tan 2015; Moraes et al. 2012; Auger and Devinney 2007) and the proclaimed ‘myth’ of the ethical consumer (Devinney et al. 2010; Carrigan and Attalla 2001). This literature also implies failure of those who cleave to an ethically minded mode of consumption which, for reasons we explain later, we believe to be unfair. Trade-offs frequently emerge as a theme in associated debates, although these are characterised differently within vying research traditions and they are often discussed in negative terms. Both their status and nature is subject to debate and there are, we argue, both epistemological and ontological assumptions that underpin diverse perspectives on how they are perceived.

Firstly, their role in determining behaviour and choice is often entangled in arguments that focus not on trade-offs per se, but on the relative merits of intensive versus extensive methodologies (Sayer 2000) and on the epistemological claims they reflect. The literature on ethical consumption divides broadly between (1) studies emphasising individual cognitive decision making (e.g. Balderjahn et al. 2013; De Groot et al. 2016; Shaw et al. 2000; Shaw and Clarke 1999; Sparks and Shepherd 1992; Thøgersen 1996) and (2) those that focus on experience and sociocultural dynamics. These, in turn, reflect emerging trends in the wider consumption canon, with identity (see, for example, Bartels and Onwezen 2014; Cherrier 2006; Cherrier and Murray 2007; Luedicke et al. 2009) and theories of practice (e.g. Connolly and Prothero 2008; Garcia-Ruiz and Rodriguez-Lluesma 2014; Moraes et al. 2015; Røpke 2009; Shaw and Riach 2011). Typically, although acknowledged in both, we find that trade-offs are inclined towards the foreground in (1), but to the background in (2), and that this is largely due to differing assumptions on how consumers process information.

Secondly, trade-offs are often discussed pejoratively as issues of anxiety or dispute, characterised by conflict, sacrifice, guilt or contradiction (Bray et al. 2011; Chatzidakis 2015; Connolly and Prothero 2008; Hassan et al. 2013; Johnstone and Tan 2015; Valor 2007). Indeed, Littler (2011) argues that ethical consumption has increasingly become ‘contradictory consumption’, whilst Shaw and Riach (2011) remark on tensions created when values and actions fail to align. We contest though that treating trade-offs in ethical consumption as something to be discounted misconstrues how they work. Similarly, that addressing these as either simple dichotomous preference balances, or as a mere backdrop to other more pressing imperatives, confuses rather than clarifies. Some recent studies (see, for example, Carrington et al. 2014; Davies and Gutsche 2016; Longo et al. 2017; and Schaefer and Crane 2005) have sought to combine some of the discrete perspectives outlined above (decision making, sociocultural and practice) and take a ‘middle ground’ approach in ethical consumption. We contend though that further work is required here to explore more fully how the weighing of tendencies are experienced and how, as a result, choices are formed.

This study therefore takes trade-offs as its central theme, and we use value as a lens through which to explore these in the context of ethical consumption. This is primarily because value embodies the ego at work, an issue that is rarely represented in work on ethical consumption (Phipps et al. 2013). Studies have examined what is valued by, or is of value to, consumers and also how this is impacted by their values (e.g. Davies and Gutsche 2016; Schröder and McEachern 2004; Shaw et al. 2005). We know little, however, about how consumers value. Consequently, we employ Dewey’s (1939) Theory of Valuation which acknowledges that consumers are not entirely without agency; that there is an element of inquiry in the process of determining value; and that value can be understood only in the context of experience. Dewey proposes the notion of a unified value which takes place in the context of ‘ends-in-view’. These are broad objectives or anticipated results that can be characterised as ideational; that is, they connect valuation with desire and interest (they are rational, emotional and based on foresight) and enacted via transient habits.

Consequently, drawing on output from an empirical study involving respondents who self-report as ethically minded, this article looks to advance a pragmatist explanation of the role and nature of trade-offs in consumption. In so doing, it draws on the central roles of value and values in both consumption and pragmatist philosophical thought. It has been suggested (Davies and Silcock 2015) that pragmatism supports a demand for rigour but makes no preferential or predetermined claims on methodological stance. Our particular contribution adheres to this philosophy by first conjoining different approaches (both structured and unstructured), and then applying Dewey’s (1939) pragmatist Theory of Valuation as a background to data analysis. In so doing, we extend the field of study that pertains to ethical consumption, but make our contribution distinctive by employing both sociocultural and experience-based analysis to explore the trade-offs that might apply. Our overall aim is to make an original contribution to this special edition’s theme in focusing on understanding the role of value in the establishment of ethical consumption practices.

Literature Review

The Fundamentals of Ethical Consumption Research

In the consumption literature, there is a substantive body of knowledge privileging individual-level decision making. This applies as much in the field of ethical consumption as it does in any other (Phipps et al. 2013). According to De Groot et al. (2016), this tends towards one of two theoretical fields: one that draws from expectancy-value theory, and the other that focuses on moral norms. Expectancy-value models suggest consumers make choices about attributes of an offering (or the offering itself) based on an expectation of that choice leading to positive consequences (Cohen et al. 1972). This theory underpins a number of consequentialist consumer behaviour models, most notably the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA—Fishbein and Ajzen 1975) and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB—Ajzen 1991), and many studies of ethical consumption are characterised thus (for example Balderjahn et al. 2013; Carrington et al. 2010; Shaw et al. 2000; Shaw and Clarke 1999; Sparks and Shepherd 1992).

An alternative approach (see Thøgersen 1996) argues for a deontologically based moral norms theory focused on altruism. This assumes a purposeful ethical ‘awakening’ that might lead to pro-environmental behaviours (De Groot et al. 2016). Stern (2000) calls this value-belief norm theory and, as with others in this tradition, grounds ideas in the typological work of Schwartz (1994) and Rokeach (1973). Both authors acknowledge that values can be ascribed in two different ways: there are terminal values (or preferred end states) set as overall goals for a successful life, and there are instrumental values (or guiding principles) orienting the consumer towards behaviours likely to facilitate those goals. These latter are sometimes expressed as virtues (e.g. Garcia-Ruiz and Rodriguez-Lluesma 2014). It is suggested thus that a link exists between ‘good’ or morally oriented personal values, ethics and behaviour, and this reflects a widely held view that values are central to consumers’ consumption behaviours (e.g. De Groot and Steg 2010; Manchiraju and Sadachar 2014; Shaw et al. 2005; Lages and Fernandez 2004).

Some have sought to combine expectancy-value and moral norm theories by proposing ethical obligation as an antecedent to intent (e.g. Aertsens et al. 2009; Shaw et al. 2000; Sparks and Shepherd 2002). Holbrook (1994) also claims consumption is not merely utilitarian and that morality contributes substantially to the choices people make. He consequently suggests that ethical benefits can be derived from behaviours motivated beyond self-interest. Collectively, these studies (both expectancy-value plus moral norms) define the three key elements underpinning mainstream research in ethical consumption: products and/or their attributes, consumption consequences, and human (or corporate) values.

Trade-Offs in Ethical Consumption

All approaches described above are to some extent concerned with trade-offs. The expectancy-value approach, for example, suggests we compare and contrast different options (attributes and/or functional consequences), rejecting some and prioritising others (De Groot et al. 2016). Similarly, our values are said to be organised as integrated motivational systems, hierarchically sorted to guide and establish option priorities (Schwartz 1994). In both cases, we are implicitly assumed to weigh the benefits and sacrifices of each opportunity (or expectation) and then act to achieve the best outcome.

A more formal notion of trade-offs as discreet decision-making processes is also found significant in emerging evidence on ethical consumption (e.g. Ha-Brookshire and Norum 2011; Luchs and Kumar 2017; McGoldrick and Freestone 2008; Valor 2007). Such studies have sought to foreground trade-offs, exploring these via distinct case-specific scenarios that focus explicitly on competing options. Devinney et al. (2010), for example, apply a ‘best–worst’ experiment in which consumers are asked to rate the relative importance of objects of conflicting perceptual difference and then evaluate the trade-off. Glac (2009) similarly considers trade-offs involving different types of functional consequence, whilst Luchs and Kumar (2017) appraise contrasting merits of both aesthetic versus sustainable product attributes and utilitarian versus sustainable product attributes. As an alternative to best–worst comparisons, others suggest cost–benefit as pertinent competing options. These focus often on how price influences consumers where virtuous options are marked higher than the competition (Auger et al. 2003; Abrantes Ferreira et al. 2010; De Pelsmacker et al. 2005; Lim et al. 2014).

The literature pertaining to trade-offs construes these frequently as conflicts that apply at a cognitive level of decision making. Hassan et al. (2013) and Schröder and McEachern (2004), for example, describe contradictions that arise from guilt and the breaking of ethical rules. McGoldrick and Freestone (2008) argue that we accrue a ‘balance sheet’ of gains and losses that are in opposition, and state consequently that this represents a conflict to be resolved. Such conflicts have been described as representing ‘difficult value judgements’ (Moisander 2007) or ‘hard choices’ (McShane et al. 2011), whilst both Johnstone and Tan (2014) and Valor (2007) refer to compromises or sacrifices made. The role of rational agency in settling internal disputes is evident in these accounts, and trade-offs invoked imply the consumer is engaged in an act of preferential judgement, balancing the relative importance of both the benefits and sacrifices of engaging in an act.

This balancing is also a central strand within work on consumer perceived value (for example Ng and Smith 2012; Sánchez-Fernández and Iniesta-Bonilla 2007; Woodall 2003), itself considered to be one of (if not the) most fundamental concepts for the study of marketing (Gallarza et al. 2011; Holbrook 1994; Vargo and Lusch 2012). Ideas most notably explored by Dodds et al. (1991), Heskett et al. (1994) and Zeithaml (1988) suggested consumers are conditioned to make rational comparisons of the good and the bad in exchange relationships, choosing the option delivering the greatest net benefit (value). As Gummerus (2013) points out, however, a perceived association with neoclassical economics has diminished the attractiveness of trade-off/benefit–sacrifice approaches, and there has instead been a call to focus on a ‘phenomenological value’ (Helkkula et al. 2012), a value that is rooted ‘in-the-experience’ (Tynan et al. 2014) or ‘in-context’ (Chandler and Vargo 2011) and that emphasises the multi-contextual and dynamic nature of value (Heinonen et al. 2013). More recent studies have consequently focused either on value-co-creation (see Vargo and Lusch 2004; where value is believed to emerge as a function of product or service use/experience) or on trade-offs and experience as contiguous entities (e.g. Woodall et al. 2014).

The Experience Turn in Ethical Consumption

The customer perceived value concept is not substantially represented in studies of ethical consumption perhaps, as Phipps et al. (2013) point out, because ethically oriented behaviour is generally considered other- rather than self-oriented. Noteworthy exceptions include Hänninen and Karjaluoto (2017), Papista and Krystallis (2013), and Peloza and Shang (2011). Only the second of these is focused on trade-offs reflecting a general loss of traction in the literature for studies of this type. Critiques mirror Painter-Morland’s (2011) view that trade-offs are based on spurious foundations, given that both aggregation (weighing up) and maximisation (optimal achievement) are likely too complex to be viable in conscious reflection. Rational information processing models (including those related to trade-offs) are still employed in the ethical consumption canon but are now just part of an evolving research tradition (Moraes et al. 2012; Phipps et al. 2013), and Janssen and Vanhamme (2015) suggest they reveal little more than the ‘tip of the iceberg’ for ethical consumption.

Schaefer and Crane (2005) and Jackson (2005) are significant for their critique of cognitive thinking, and have been influential in the development of a substitute focus on social and cultural backgrounds as a guide to behaviour. An important strand of the more recent literature on ethical consumption—developed after the influence of consumer culture theory (Arnould and Thompson 2005)—has thus emphasised the importance of sociocultural dynamics and the concomitant role of identity (see, for example, Bartels and Onwezen 2014; Carrington et al. 2014; Cherrier 2006; Cherrier and Murray 2007; Luedicke et al. 2009). According to Arnould and Thompson (2005), the real world is not transparently rational, and although they acknowledge ‘the compensatory mechanisms and juxtapositions’ that underpin behaviour, their key focus is on consumption as a procedure that is contextually symbolic and experientially driven.

A key aspect of associated research has consequently been a focus on experience, and these studies are often epistemologically distinct in drawing on storied invocations of peoples’ lives for their data. They challenge the received wisdom around the ABC (attitude, behaviour, choice; Shove 2010) of consumer activity that draws often on numerical data and/or assumptions of deliberative choice. Studies tend to argue that consumption is not induced by specific observable stimuli but exists instead within a web of interacting and experiential phenomena (see, for example, Black and Cherrier 2010; Carrington et al. 2014; Longo et al. 2017; Shaw et al. 2016). Apparel purchase (the context for our study) is also represented (e.g. Bly et al. 2015; Markkula and Moisander 2012). This work is consistent in surfacing the complex nature of ethical consumption and the multiplicity of agendas that apply.

Agency and the Ethical Consumer

A further approach deployed recently in consumer research is that concerning the ‘practice turn’ (Schatzki et al. 2001). Nicolini (2012, p. 3) summarises practice approaches as ‘fundamentally processual’, appreciating the world as “an ongoing routinized and recurrent accomplishment”. This advocates a sociological lens focused on habits, and Warde (2005) submits that consumption occurs thus in the context of tacit understandings rather than conscious reflection. Practice theories have been taken up both by those with a broad interest in consumption (e.g. Goulding et al. 2013; Halkier et al. 2011; Skålén et al. 2015) and also those with a special interest in ethical consumption and environmental behaviour change (for example Connolly and Prothero 2008; Garcia-Ruiz and Rodriguez-Lluesma 2014; Moraes et al. 2015; Røpke 2009; Shaw and Riach 2011). Here, social practices are taken as the everyday and ordinary, enacted in routine and oriented (or not) towards ethical behaviour. Hargreaves (2011, p. 83) cites Reckwitz who suggests practice theories remove individuals from centre stage, regarding them instead as ‘carriers of social practices’, performing duties ascribed by the practice itself. Moraes et al. (2012), for example, suggest we can better understand the drivers of ethical behaviour by examining everyday habits of consumption rather than by measuring how consumers rationalise their individual inconsistencies.

Carrington et al. (2014) describe links deemed to exist between core ethical consumption values, the integration of habits into lifestyle and finally, ‘consumption enactments’. They establish the potential for personal values to underpin the development of practices, and consequently acknowledge that routine consumption contexts are individualised at least to the extent that values, also learnt, are of a distributed nature. A similar sense of linked relationships occurring between values and consumption is found within research using Gutman’s (1982) means-end chain. This conjoins product/offering knowledge and self-knowledge at primary level, and suggests a linear and causal chain of effect between attributes, functional consequences, psycho-social consequences, guiding instrumental and terminal values (Mulvey et al. 1994).

As with expectancy-value theory, means-end research assumes consumers centre the attributes of an offering, chiefly those delivering preferred outcomes or ends (Jackson 2005). However, when using soft laddering (a semi-structured interviewing technique used to explore links within the chain; Phillips and Reynolds 2009), it also invokes experience as a transitionary stage between the two, stressing also the role of values in shaping this experience (Davies and Gutsche 2016). Also, by emphasising both functional consequences (occurrences) and psycho-social consequences (feelings) the potential for being as well as doing in an ethical context is acknowledged (Shaw and Riach 2011). Studies of this kind have recently increased in number (see, for example, Davies and Gutsche 2016; Jägel et al. 2012; Lin and Lin 2015; Lundblad and Davies 2016; Zagata 2014). Jägel et al. (2012) are significant in identifying the integrated nature of trade-offs and values in consumption practice, whilst Lundblad and Davies (2016) describe ethical choice as a problem solving rather than cognitive rationalisation dilemma. They note also it is mostly egoistic (self-referencing) rather than biospheric/altruistic (society-referencing) ideals (Stern 2000) that drive behaviour.

This latter contributes to an emerging view in ethical consumption research that ‘it’s not easy living a sustainable lifestyle’ (Longo et al. 2017). Forays into the realm of experience demonstrate that moral behaviour is not a discreet entity, divorced from the broader challenges of life and practised within a social vacuum. There are myriad personal and situational concerns that render this a contingent rather than predictable endeavour, and—given the nebulous and temporarily obscure nature of ‘saving the planet’—even those with distinct environmental/universalist concerns will ask, “what’s in it for me, now?” However, in espousing a motivational focus either on identity formation, on habit, or on enduring values, researchers reinforce the sense that agency is conferred rather than deployed, and though contingency has been observed to exist as micro undertakings in personal ‘consumption enactments’ (Carrington et al. 2014) its source is considered macro by default.

We return, therefore, to a theoretical domain that forefronts the individual, that of value as perceived in reflection. However, rather than revisiting the marketing texts referred to earlier we take as our next point of departure moral philosophy, and particularly that espoused by John Dewey. As we will show, Dewey’s work encompasses much of that we have discussed thus far: individual decision making, experience, habit and ethical/moral behaviour. However, Dewey views morality as a practical enterprise that is grounded in pragmatism. And whereas newer means-end approaches have sought to offer an epistemologically pragmatist approach to ethical consumption research (for example Davies and Gutsche 2016), this next section takes ontological perspectives on pragmatism as its cue. Rather, though, than exploring what value is we focus on how it is formed.

Dewey, Pragmatism, Ends-in-View and Aggregations of Value

Whilst phenomenological and practice perspectives on consumption address some of the problems of rational/utilitarian models or value/trade-off models, we believe, as Dewey (1939) argues in his Theory of Valuation, that there is a cognitive element to valuation. As Dewey notes, a theory of valuation must necessarily include both a psychological and a sociological dimension, as humans exist in a cultural environment that shapes desires and ends and, therefore, valuations. John Dewey, philosopher and psychologist, was amongst the first wave of pragmatists (including Charles Sanders Peirce and William James) that emerged in the United States in the period spanning the end of the 19th and the early-to-mid twentieth centuries. He held a profound belief in democracy and in the effectiveness of a solution rather than the authority of its source (Bertman 2007). Although pragmatism, per se, has been invoked frequently in the field of marketing and consumption (Silcock 2015), Dewey’s theories have only occasionally been used (see Chakrabarti and Mason 2015; Hatch 2012; Bruner and Pomazal 1988): his Theory of Valuation (a ‘consistent and richly elaborated’ perspective; Mitchell 1945) even less so, an exception being Davis and Dyer (2012).

Dewey (1939) suggests the formation of ethical or value judgements cannot be viewed in isolation of individual acts; they must grow both from experience and from existing valuations. Any impasse between a scientific view of behaviour and the emotions which dominate practice is inherently problematic he suggests, and this impasse is manifest in divisions characterising ethical consumption research as outlined earlier in this article. Further, although objections to cognitive and functional approaches to ethical consumption are theoretically well-grounded, in 1925’s Experience and Nature (Dewey 2016, p. 398) Dewey notes that: “possession and enjoyment of goods passes insensibly and inevitably into appraisal”. This appraisal, or valuation, does involve thought and synthesis (as in the acts of preferential judgement described earlier) though objects in themselves are not perceived to possess any intrinsic ‘value-quality’ which can be ordered or ranked. He argues (Dewey 2008a) that valuing (liking or rendering important) may differ in its intensity, but each cumulative and sequential interpretation replaces another through a process of improvement and cultivation. Thus, these are not absolute, they emerge through experience and are—as Chandler and Vargo (2011) also suggest—context dependent. The outcome of valuation is effectively an aggregation of diverse perspectives which, as Dewey suggests in 1934’s Art as Experience (Dewey 2005), is also consummatory and exists as a concluding unity in which one property, at some point, is sufficiently dominant to characterise experience as a whole.

Dewey’s notion of a consummatory unified value takes place in the context of ‘ends-in-view’ (Dewey 1939). These are broad objectives or anticipated results that can be characterised as ideational; that is, they connect valuation with desire and interest (they are rational, emotional and based on foresight) and are practised through transient habits. With respect to values, and commensurate with the discussion on morality above, Dewey (1939) further argues that humans are continuously engaged in a process of learning, adjusting the way they feel or desire. He argues further that values are an expression of feelings, and to claim these are unchangeable (as, perhaps, expressed in moral norm theory) is contrary to common sense. He argues, however, that ends cannot be placed ‘in view’ until a subject knows the resources and objects necessary to enact the journey and to arrive at that end. Thus, ends do not subconsciously guide action; they are determined reciprocally and recursively via the means of action that are entrenched in habits and arise out of experience, and are enacted in predictions of what might happen in the future, and what has happened in the past. In terms of action, Dewey (1983) argues that individuals ‘shoot and throw’, initially instinctively, and the result then gives new meaning to the activity. Ends, accordingly, shift constantly as new activities result in new consequences, and thus apparently conflicting positions need not necessarily be mutually exclusive. However, aims can only become ends when the conditions for their realisation have been worked out. Both of these factors (ends-in-view and the conditions for realisation) are a natural part of an ever-shifting experience of value.

This pragmatist view therefore rejects non-contradictory philosophical positions and views morality not as a set of principles which (a) guide everything and (b) must be followed, but as a journey characterised, as Dewey (1983) suggests, by ‘endless ends’, cumulatively and sequentially re-imagined as new habits and experiences come into view. Our study, therefore, is informed by a pragmatist perspective that simultaneously acknowledges both cognitive/utilitarian and phenomenological/practice perspectives on consumption and value. We believe that trade-offs are likely to exist in the practice of ethical clothing consumption, but are unclear as to how these occur in experience. Our overall aim is to seek insight into the processes that facilitate and enact valuation and in exploring the trade-offs we believe to occur in the development of practices. Clothing is selected as a context due to the numerous ethical problems which continue to characterise the sector (Brooks 2015) and because of the myriad social and cultural influences that impact an individual’s clothing choices (Michaelidou and Dibb 2009; Dawes 2009; Carpenter and Fairhurst 2005).

Methods

Our methodological approach is congruent with the pragmatist stance we outline in the previous section. Varey (2015, p. 213) argues that in pragmatist thought knowledge emerges through ‘intelligent reflection on experience within nature’ and the ontological view of value is subjective; it emerges through lived experience. As Dewey (2008b) notes, truth depends on what individuals find through observing reflectively on events, and Testa (2017) provides a view of Dewey’s social ontology which is one of habituation, rooted in a recognitive process of dependence on, and learning from others. This requires the use of particular methods for capturing an ontology of changing habits, co-dependent lived experiences and personal narratives around the enactment of value as they occur. Working at this level leads us to the adoption of qualitative techniques, and in particular in-depth interviews, where our aim is to search for evidence of trade-offs made by ethically minded individuals. Here, our objectives are threefold: (1) to explore informants’ sense of morality as consumers and those moral issues which are particularly important for them; (2) to explore whether those moral issues are embedded in values; and (3) to discover how value is aggregated through experience from specific purchases. It is Dewey’s (1983) attractions and aversions that characterise experiences, and the factors that help constitute these, that we seek to reveal.

In order to achieve our aims, we adopt a purposive sampling strategy and focus on individuals who self-identify as ethically minded consumers (Carrington et al. 2010). That is, those with some ethical motivation or values; with a degree of ethical knowledge (Tadajewski and Wagner-Tsukamoto 2006; Carrigan and Atalla 2001); and who are likely to seek to manifest their values through consumption practice. This broader view of the ethically minded consumer is preferred to the more narrowly defined ethical consumer (e.g. Shaw and Riach 2011) that suggests an ability to fully evaluate and successfully adapt consumption behaviours in response to ethical concerns. This also distinguishes informants from those identifying purely as green (e.g. Johnstone and Tan 2015) or sustainable (e.g. Connolly and Prothero 2008). Indeed, ‘ethical consumption’ implies a wider schema that may “combine, overlap, conflict and vie for attention” (Newholm 2005, p. 108) with other related agendas and extend to any practice which is integrated into an individual’s search for a morally good life (Garcia-Ruiz and Rodriguez-Lluesma 2014).

Our informants, likely to perceive ethics as important in both personal and professional life, were drawn from ethically oriented UK university research groups over a wide range of academic disciplines. Some, given the nature of sustainability issues, naturally considered themselves to be cross-disciplinary. Our sample comprised respondents from different sociodemographic/national groupings, thus supporting diversity and representativeness. Access was gained via group leaders and by deploying personal networks. Snowballing allowed us to extend beyond our immediate list of contacts and our strategy led to a sample that was both theoretically and constitutively apposite. Borrowing from, though not obligated to, grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin 1998), the sample was determined in response to ongoing analysis (Morse et al. 2002) until saturation occurred (Fusch and Ness 2015). Respondent details can be found in the Appendix.

The structure of the interviews was framed initially using ‘grand-tour’ questions (Spradley 2016). In our context, these were general questions about respondents’ consumption and aspirations for morality in consumption which help set the direction of the interviews. These were then followed by ‘long’ questions (McCracken 1988) designed to draw out in-depth accounts of experiences grounded in specific purchases. A typical question was: ‘Can you tell me about the last time you went shopping? What was going through your mind when you bought/used that item’? During interviews the researcher shared personal thoughts and feelings so as to reconstitute a ‘question and answer’ event into a conversation. Each interview lasted for around one hour, limited only by the constraints of the topic and the desire to avoid repetition and irrelevance. Ultimately, twenty interviews took place, after which theoretical saturation was deemed to have occurred, also meeting recommendations on sample sizes for qualitative interviewing (Cherrier 2005; Guest et al. 2006; Kvale 1996; Miles and Huberman 1994). Transcription and analysis were undertaken immediately following each interview.

For analysis, we adopted a process of reflexive interpretation (Alvesson and Sköldberg 2000; Thompson 1997). Arnould and Fischer (1994) note that the emphasis on pre-understanding in hermeneutics recognises that both interpreter and interpreted are linked by a ‘context of tradition’, and that this precedes analysis and interpretation of a text. This provides for a point of departure that enables the interpreter to make sense of narratives or objects observed, or ‘root metaphors’ of pre-understanding (Alvesson and Sköldberg 2000). This method synthesises some of the benefits of data-oriented approaches (such as grounded theory) with hermeneutics geared towards active interpretation. It also acknowledges that data are difficult to absorb in one pass, and that there is a need for iterative interpretation at successive theoretical levels, mixing empirical work, meaningful interpretation and critical reflection.

Thompson (1997) notes that hermeneutically oriented analysis in research typically follows a staged process; there is an intratext cycle in which a text is read in its entirety, and a subsequent intertextual cycle (that may comprise several passes) where ‘plots’ across texts are identified. This means analysis is not merely informed by cumulative inferences from individual transcripts, but that data are considered a recursively interweaving whole. For our analysis, we deployed two distinct phases of data translation. The first, using NVivo software, sought to establish the characteristics of purchase and consumption significant for this group. Here, we initially established a content pattern from our raw data, thereby identifying the key characteristics, or units, of meaning embedded within the interview transcripts. Next, through a process of both a priori and in vivo coding we sought to establish a broader frame of understanding that could be used as a platform for further interpretation and analysis.

This second phase of analysis was used to position our relatively structured perspective on clothing consumption in a wider and more considered domain of enquiry. Here, through repeated transcript readings, we developed an interpretation of informants’ personal narratives to construct an understanding of how/why both units and themes might have meaning from a value perspective. This led to the construction of ‘hermeneutic lenses’ through which the newly themed data could be examined, using Dewey’s (1939) Theory of Valuation as our ‘root metaphor of pre-understanding’.

Results

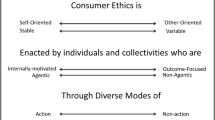

Figure 1 illustrates both schema and outputs from our analytical process. The white boxes are discreet units of consumption-related meaning derived from a first-level analysis of respondents’ transcripts. These have been extracted using NVivo software and are linked to show how units interrelate and, in some cases, dependently interact. The grey boxes (with normal type) represent themes expressed by those units. We used ‘benefits’, ‘sacrifices’ and ‘values’ as a priori codes to thematically capture those units embodying the trade-offs likely to be invoked by particular ends-in-view. Then, through analysis of surplus/remaining units we identified in vivo codes—aspirations, context, habit and identity—that served to thematically situate these trade-offs in respondents’ lives.

Our second phase of analysis surfaced five key value/value-related commentaries focused on Dewey’s ends-in-view for ethically aware consumers (Fig. 1, grey boxes, italic type). These, our hermeneutic lenses, were—ends-in-view: emerging values and aspirations for ethical consumption; the formation of values and habits through experience; value judgements (trade-offs) in experience: the paradoxical nature of benefit and sacrifice; changing habits and ends-in-view; and finally, valuation enacted in practice. These are addressed sequentially below, and we use excerpts from transcripts to illustrate and link an argument that we subsequently synthesise in a concluding discussion.

Hermeneutic Analysis of Value Meaning Construction

Ends-in-View: Emerging Values and Aspirations for Ethical Consumption

Represented primarily as aspirations, we are seeking to understand the ‘ends-in-view’ as ideational objectives which are then practised through transient habits (Dewey 1939). The following quote from Chris best summarises the overall approach taken by respondents:

My aim, I don’t know if I’ve achieved this, is to buy less but buy quality that lasts. (Chris).

All respondents suggested their purchasing (or at least their consumption desires) centred around buying fewer items and those which would last. This was considered distinct from positive (Harrison et al. 2005) or affirmative (Carrigan et al. 2004) purchasing, or from consumer resistance (Newholm and Shaw 2007) given there was little evidence of preferring specific retailers/manufacturers with overtly expressed ethical policies or standards. There were exceptions (including some avoidance of particular brands) but most informants were motivated by a general desire to avoid waste and to champion environmental sustainability in their search for the morally good life. As Doug outlined:

You try and make sure that you avoid waste wherever possible… in normal consumption… I think that’s a moral imperative that all of us should try and be as responsible as we can with the planet, with waste, with whatever. (Doug).

However, sustainability was also considered important, though the issues here were not always clear, and distinction between the environmental and the social was frequently blurred (Bartels and Onwezen 2014; Carrington et al. 2010). For instance, elements of both social concern and of protecting nature were seen to correspond and interact. Of course, other concerns were also prevalent, especially in relation to fit and style and, as Meryl identified, solutions that were complementary were also encountered:

I sort of identified certain shops that I know I liked to shop at because I feel that the garments will last. It’s really about lasting for me and they’ve got to fit as well. (Meryl).

It was suggested earlier, drawing on moral norm theory (e.g. Stern 2000), that values are considered important in determining behaviour. Interviews revealed different values to be important, especially those which could be broadly related to universalism, benevolence and tradition (Schwartz 1994). However, these interacted and sometimes contradicted (though rarely conflicted). For example, many respondents flagged benevolence as a value in relation to caring for others, but also (and more commonly) from a socialised tradition of frugality, the value of ‘being careful with money’ and avoiding indebtedness. Naomi explained:

But, I suppose they [my parents] were very much of the school of ‘make do and mend’. They were born during the war and so, they were quite frugal, even though they’re perfectly well off. They were very anti-waste and also anti- “spending money just for the hell of it”. (Naomi).

Thus, as noted in the literature review (e.g. Moraes et al. 2012), we find some support for values underpinning practice, but observe that personal and situational factors are also evident, as also is conscious reflection. The holding of beliefs rooted in local/family traditions is extended below, and considers how values and self-identity emerge through history.

The Formation of Values and Habits Through Experience

A cultured practice of waste avoidance or being careful with money was explicitly expressed as being passed down from parents, and was rooted in childhood experience. As Sarah says:

And I have been brought up by my parents to be quite thrifty. I think it’s generational for them. (Sarah).

For others, family traditions and activities informed habits and values in different ways, but also connected strongly with self-identity, and this was manifest in conspicuous clothing choices. For example, Steve directly linked his values to his upbringing:

I suppose in many ways it [an environmental awareness] did influence the sort of degree I took – I remember writing something in my personal statement about an affinity with the outdoors. So that, I suppose, in some ways feeds through into my dress sense and the functionality aspect of it. Yeah, so it’s about getting outside and going walking in the countryside… I definitely remember when we did those sorts of things, that’s the sort of time I enjoyed. So we used to go walking quite a lot with my Grandad and did quite a lot of fell running and things like that with my Dad. (Steve).

For Susan, her family position had resulted in a particular orientation:

But I think that I must have had an innate sense of doing good and being interested in that, and I think getting praised for doing well… I was a middle one of four children, so classically you don’t get noticed if you’re in the middle… and the thing that got me noticed was if I did well at school... So doing well and doing the right thing seemed to be something that formed part of my identity from being in primary school. (Susan).

As Grønhøj and Thøgerson (2009) find, there are significant relationships between parents and children across all values domains, and they find this especially true of pro-environmental attitudes. However, whilst this study supports the intergenerational influence of values, this was never explicitly expressed in terms of pro-environmental behaviours. Rather, values linked to sustainability, for example, were more often situated in a broader history of love for the outdoors and nature, often invoked through romanticised stories of childhood; or even via security-driven virtues developed in households that were careful with money and avoided waste. Thus, as Dewey (1939) suggests, the formation of ethical or value judgements develops both from experience and from existing valuations, and morality cannot be separated from other values which emerge through experience.

Further, in contrast to Jägel et al. (2012), informants rarely spoke of values conflicts, except in relation to the most contextually specific, utilitarian and micro-level decisions. A general sense of ease and comfort towards clothing consumption implied that individuals’ values were largely upheld. Purchases were rarely discussed in negative terms, and there was no evidence of guilt, remorse or regret based on conflicting values. Buying behaviour was frequently driven by habit and custom, and informants’ repertoires of preferred retailers and brands were typically small. These were largely long-established and engrained in custom and practice, often with roots in childhood. As Nick and Liz observed:

Growing up it was Levi’s and it’s not even probably a decision because they’re Levi’s. (Nick).

Marks and Spencer because I’ve just grown up with it and it provides me with my basics… you can walk right through it and within ten minutes have purchased everything that you need without any real thought ... that’s my idea of shopping! (Liz).

Shopping habits were primarily passed on from close communities of practice and developed through time, minimising any need for continuous cognitive evaluations. Naomi described her strategy for buying a new shirt (due to starting a new job):

I need a shirt for work. I believe Gap to be my most likely chance of getting a plain shirt. And therefore, I’m going to go to Gap and buy the best shirt in Gap… It’s… knowledge that has gradually built up over a couple of decades. That’s because, with family, with friends, other people who typically like shopping. And so, on those occasions, then I would’ve been in those shops. (Naomi).

This process of developing habits through learning over time appeared to operate at a subconscious level and was evident for most of the respondents. As Vivian explained:

I know certain brands, if you like, that kind of fit all right that are kind of not too expensive but will last… I think I do things because they’re habits… I don’t really look to change that habit very actively. (Vivian).

Value Judgements (Trade-Offs) in Experience: The Paradoxical Nature of Benefit and Sacrifice

Our understanding of value is derived largely from Woodall’s (2003) work on ‘value for the customer’. This implies that trade-offs are performed via contributing factors consciously organised as either benefit or sacrifice and that such polarity is manifest in valuations. Our data, though, challenges this in two ways. Firstly, a distinction between attributes as either benefit or sacrifice was not always clear. Issues identified in relation to social benefits and identity, for example, could be benefit or sacrifice—benefit in terms of being accepted by peers for dressing a particular way, or sacrifice for not doing so. Even price, that most immutable of sacrifices, could operate as a benefit: either as a signal of quality (good value) or a sign of generosity. As Susan outlined for buying a dress from an ‘ethical’ retailer:

If you buy that you’re giving People Tree more money, and they fund schools, and I felt like it was sort of making a charitable donation, but I get something out of it as well... So, I use the term ‘donate’ rather than just ‘buy’ because it is quite a different thing. (Susan).

Similarly, whilst ethically produced clothes could potentially provide benefit for those engaged in positive purchasing, initiatives such as Fair Trade, or problems with style and identity, could be viewed negatively. In Johnstone and Tan (2014), for example, the term ‘eco fashion’ was discussed in pejorative terms. Our respondents raised similar issues, typified by Chris and Naomi:

…you know it’s from a Fair Trade shop, let’s just say, because there’s acertainstyle, isn’t there? If you’re buying that sort of thing for work, it’s not necessarily always going to be appropriate. (Chris).

It [an ‘ethical’ top] would say something about the person wearing it, about their ideals, that they were environmentally aware but in a green and ‘waffy’ kind of a way. There’s definitely a distinction between certain kinds of green people! (Naomi).

In the same way that attributes of value could not always be distinguished as either benefit or sacrifice, we note that both benefit and sacrifice themselves could co-exist in the same attribute. Thus, a perceived attitude–behaviour gap might more pragmatically be played out as an attitude–behaviour compromise that resolves the disparity between two apparently competing ends. As Susan observed:

But what I will do is I’ll sometimes buy more expensive clothes… so a lot of these things that actually sound like terrible things that women would do, like going to the sales and buying really expensive stuff, are actually sustainability in disguise things! (Susan).

Thus (stated) behaviour of reducing the amount of consumption but increasing spend is justified as sustainable behaviour; there is no conflict between saying or thinking ‘x’ and doing ‘y’. Elisabeth adopted a similar strategy, but in this case the dissonance that arose from purchases she perceived to be less ethical was compensated by acknowledging the boycott of another retailer. Thus, informants described issues around trade-offs when speaking hypothetically about their attitudes, preferences and behaviours, but examples given of purchases in the consumption stories were not consciously considered as such.

Changing Ends-in-View and Practices

For others, changes in practice had shifted ends-in-view. For example, for Daphne, time spent studying overseas had developed her already-keen sense of social justice into a wider concern for the environment and nature:

I had an opportunity to go to Finland … that experience changed my life in terms of why I got interested in sustainability because I saw how Finland as a society works… [it] opened my eyes to other perspectives as well about caring for the environment, and about caring for society and their wellbeing. (Daphne).

Similarly, for Sarah a serious health scare had caused her to develop her knowledge of organic produce, which then reinvigorated her childhood love of nature and further developed into a concern about global environmental issues. James discussed how a change at work and a corresponding shift into a more mature stage of his life had led him to rethink the clothes he wears, blurring the lines between work and casual:

At work I felt like … at times, that whole awkward smart casual… suits are a bit formal but then there’s times when you are going for meetings and it just felt like you wanted something, but I didn’t want to have something just for work actually… I like to have a sense of fluidity between when I work and my social life. I don’t view my job there and my social life here – so there’s a sense of a merging and a blending. (James).

As Appiah (2006) argues, justifications of our acts are typically made post hoc, with intuition a by-product of upbringing and lived experience. Justification (or reasoning) only happens when thinking about change. Similarly, for Dewey, acquired habits require little thought and are for the most part instinctive, with action guided by ‘what comes naturally’ (see also Hargreaves 2011; Warde 2005). This was seen primarily in participants’ explanations of where they purchased, determined from within a clear historical development of habit. Valuation (or conscious deliberation) occurs only when routine is no longer sufficient. Value judgements are then tested in practice and revaluated. Dewey (1939, 1983) therefore refers to ends-in-view rather than absolute end states, and for pragmatists, means and ends are ‘reciprocally determined’. That is, the end cannot be completely conceived until one understands what must be done to arrive at it. Both ends-in-view, and the conditions for their realisation, are a natural part of an ever-shifting experience of value that was often evidenced in our transcripts. Chris’ description of shifting consumption habits typified this:

The high street is easy. You just walk by… and they’re easy to go into, aren’t they?... But I think if you want to buy something that’s a bit better quality, you’ve actually got to think about it a bit more, I’ve got to engage with it more as well. And then, we wanted to try to buy more ethically…it’s a purposeful decision. So, I think it’s that shifting… it’s making yourself decide that’s how you want to do it. And then, you’ve got to transition to get yourself into that habit. It’s a process really. (Chris).

Thus, practical judgement is creative and transformative in continuously reshaping new ends. That is, individuals engage in clothing consumption practices that emerge from a lifetime of learning, experience and identity pressures, and they shift in relation to life changes, whether concrete (such as moving to a new country or changing job) or perceived (like maturity, or personal growth). Thus, the retailer set frequented by respondents (their habit) was relatively stable, and only changed when personal events drove the search for new styles or brands.

Valuation Enacted in Practice

Here we use examples of coat buying to illustrate our point. One concerns a purchase from Marks and Spencer, another a failed search for a winter coat, and a third involves a Barbour Jacket. Meryl, our subject for the first, draws on work-derived habit to explain her practice:

Well, I knew that I’ve seen this one in Marks and Spencer so I went back to the Marks and Spencer in Birmingham. I didn’t really look at any other coats. I just liked a particular coat that .... I’d seen. (Meryl).

Meryl’s routine and unquestioning use of Marks and Spencer is rooted in a desire for quality, established via her long-standing career in the clothing industry. This was instinctive, requiring little conscious deliberation. Her values are embedded in habit and leave her ethically minded principles intact; both could intuitively be accommodated in the same purchase. This conviction characterised much of Meryl’s, and many other respondents’ buying. Contrast this with Daphne’s search for a coat to help her adjust to UK winters:

It’s time to replace my winter jacket but I have trying to find a good winter jacket that could last longer than five years. I take time to make that decision – two months now… probably about 20 stores… I know it’s very difficult to get one that is completely water proof [but] I saw one that was really, really nice, I don’t know, but it was like about £300 and I said well, it’s very nice, it’s a proper winter jacket but it’s not really a jacket that in the UK we will be using that often because that winter jacket is for minus 10 degrees... What I’m trying to find is something that the material could kind of repel the water, has a hoody, and a kind that I could use for everything. The things I have been finding are nice looking … but the quality is not really good… several times I had problems with zippers… and I go with my husband and he started telling me, “You have to buy something with this quality, that is good looking...” blah, blah, so it was just like this constant fighting so I just tend not to buy anything. (Daphne).

Here there is a clear cognitive dimension to a (yet to be undertaken) purchase for a respondent who has recently arrived in a new country. As Dewey (1939) explains, the appraisal of something is to judge it in relation to the means required to attain it, and consequently appraisal is fundamentally practical. However, as the respondent explains, the cost of acquiring the thing she really wants is unjustifiably high and, because of quality problems, the brand she prefers for other reasons is valued less. Further, the act of evaluating the coat cannot be performed properly until she knows how the coat will function under predicted circumstances and she understands how suitable it will be. She is also aware of her husband’s views, and because she cannot readily resolve all these dilemmas her ‘end’ has now become to avoid turmoil rather than buy a coat.

Finally, Sarah discusses her purchase of a Barbour, revealing how habit might be established in response to perspectives on value, rather than the reverse.

I bought a Barbour a couple of years ago, and I thought, “this makes sense to me on so many levels. This is going to be a garment for life.” It does the job. It’s built for rainy days, that’s the whole purpose of it. They can repair it. You can re-wax it… So that appeals to me on several grounds, not just ethical grounds, because they’re made in UK, aren’t they?... Anyway, that appeals to me… You’d spend a lot of money on it. But it’s lovely thinking “that’s it”, and it’s a lovely coat. It does the job. And I like the colour, it’s dark green. This is going to last me a lifetime and that really appealed to me. (Sarah).

As for Daphne, product evaluation can only take place following enactment in use. Sarah may discover the coat is not made in the UK; her tastes in colour may change; she may not want a ‘forever’ coat; the job of re-waxing may become too expensive or arduous—at which point desired ends may change and habit may shift accordingly. However, her story takes on a different meaning when contextualised against something revealed later in the interview:

It’s actually an impulse buy (laughter). My husband and I were in John Lewis one day and I said, “Oh, look, a Barbour.” And I … always wanted one because I knew someone years ago who had one and we lived in Wales, so it was continuously chucking it down with rain. And they had Barbour coats and I remember thinking, “I really want to have one, they look good.” And I saw a Barbour, “Oh, they really look nice.” And I tried one on. And my husband says, “Well, that really suits you.” I said, “It does. I like this.” (laughter) And I knew a bit about the brand, anyway, Barbour, the fact that it is meant to be for life; it is a lifetime garment, and it really appealed to me. I just thought, “Great.” (Sarah).

This further passage reveals the combined roles of routine behaviour (shopping in John Lewis), of relational others, of history in shaping the self (‘them’ in Wales) and of perceived value justification (made in the UK, lasts a lifetime, looks good) after the fact.

Thus, as Dewey (1983) suggests, ethical evaluation is not focused on the ‘end’ or other supreme principle as suggested by the means-end literature (Jägel et al. 2012; Gutman 1982). Rather, it is a process for either improving or explaining value judgements, especially when actions seem out of place or are questioned. Understanding the role of value for ethical consumption in this way reveals it no longer to be about principled acts which are subsequently evaluated as success or failure. Instead, it can be seen to assist the justification of habits that are constantly re-evaluated, re-negotiated and re-habitualised as individuals engage in practice. This is a form of trading-off, but one more focused on habits, values and ends than on product attributes. Thus, although it may appear, for example, that price, style and durability are being compared in conscious thought, these are instead rationalised, in reflection and reactively, to more substantive underlying determinants of behaviour.

Concluding Discussion: Everything Flows—Value and the Consummatory Experience

Our study is couched primarily in the context of experience, drawing on ideas advanced by John Dewey, in a social ontology of habit and via an epistemologically liberal, pragmatist approach to method (see, for example, Davies 2015; Martela 2015). Dewey’s (1939) warranted assertions emerge from enquiry into a world that is dynamic, and into ‘things lived by people’ (Boyles 2006). He advocates an approach to enquiry that aims not to establish an uncontested truth but to catch and describe things that are ‘on the move’.

In exploring the consumption stories of ethically minded and knowledgeable consumers, we show that whilst their practices might not accord with normative definitions of ethical consumption (Carrington et al. 2010; Newholm and Shaw 2007), consuming more ethically is an ideal to which this group aspires. They achieve this though, with varying levels of success. In adopting a pragmatist view of value, we find this group are, themselves, ultimately pragmatic in trying to be the best they can, and do not conform to the notion of the ‘hysterical subject’ (Carrington et al. 2016). Indeed, we find support for Garcia-Ruiz and Rodriguez-Lluesma (2014), who contend that ethical consumption is limited neither to the purchase of goods/services that are defined as ‘ethical’, nor to participation in social or political causes related to consumption practices. Rather, ethical consumption extends to myriad practices, which are integrated into an individual’s search for a morally good life.

Our respondents appear to suffer none of the anxiety found by Longo, et al. (2017) and Connolly and Prothero (2008), nor the sacrifice (Johnstone and Tan, 2014), guilt (Bray et al. 2011), conflict (Hassan et al. 2013) or contradiction (Littler 2011) identified by others. We find evidence for Dewey’s (1939) assertion that morality is shaped by ends-in-view which are ideational (connecting valuation with desire and interest) and which are determined reciprocally and recursively via means of action that are often entrenched in habits. The end-in-view here is to be more ethical in consumption, principally by confronting the tenets of overconsumption (by buying less and/or preferencing that which is more durable). Our evidence suggests this particular end-in-view is in constant flux and, for some, more part of a ‘symbolic discourse than an actioned agenda’ (de Burgh-Woodman and King 2013).

This is primarily due to competition between overlapping life events and priorities; evolving personal and social roles; and values that are emergent in experience (see also Carrington et al. 2014). Indeed, ends can never be absolute (Dewey 1939) as changes are significant in shaping habits which adapt as options for enhancing life experience and are perceived to materialise with, and over, time. Values, similarly, although likely established by adulthood (Schwartz and Bardi 2001) will manifest in many ways at different times, surfacing one day and being suppressed the next. We find, consequently, that consumers work to cope with that which is emerging (the ‘things’ in front of them); things already emerged; and the things inherited and embedded in habits. Consequently, we challenge Littler’s (2011) observation that ethical consumption should be characterised by its ‘failures’ or ‘contradictions’. But nor do we view ethical consumers as mythical or illusory; they are, rather, an entity that exists but is never fully formed.

Further, our evidence supports that of other commentators (e.g. Chatzidakis 2015; Davies and Gutsche 2016; Janssen and Vanhamme 2015) that the ethically minded consumer is not a rational decision-maker per se, always involved in lucid deliberation, consciously pitting one option over another. Informants’ stories frequently contain evidence of complex, but repetitive patterns of attributes, preferences, morals, values, desires, identities and relationships that contribute to value. There is a sense also that these are assimilated in trade-offs—albeit at sundry levels of consciousness that are beyond immediate assertive recall. Further, they are not readily recognised as either always benefit or sacrifice, but are accounted for in different ways at different times. Evidence from our research suggests that respondents cannot disaggregate contributing components of value nor make sense of these individually. Reflection however does occur, but at a heuristic rather than deterministic level of thought with no fixed perspective in mind.

Drawing on Dewey’s (1983), assertions about the ‘fuzziness’ of the boundaries of the self, Rorty’s (1999) notion of the polychrome patchwork quilt is a metaphor for similarly shifting norms. Here, moral choice is not between an objective right or wrong; rather, this takes place in situationally distinct contexts comprising contingently dependent options competing for attention. We therefore propose that benefits and sacrifices should not be perceived as opposing ends of a continuum or as quantitatively determined components of some form of calculative structure. Borrowing from Quantum Theory (see Wilczek 2016), we understand these as entangled; that is, with any component, attribute or dimension of value seen potentially as both/either benefit or sacrifice, dependent upon who is performing the evaluation, when they perform it, and under which circumstances they perform it.

However, a patchwork quilt—no matter how complex—can ultimately be formed to achieve a defined point of arrival, and it is here that the analogy fails to gel with our evidence. Due to their fuzziness and fluent, pluralistic and overlapping nature, the components of value, variously existing as either benefit or sacrifice, dependent upon observer and perspective, are conjoined to represent ‘perceived personal advantage’, and this we suggest exists primarily as a justification for observed behaviour. This, in turn, may be called in to question when personal and contextual circumstances change. As Bourdieu (1992) argues, thoughts and actions are governed by a small number of polysemic ‘generative principles’; both closely interrelated and constituted into a practically oriented whole. This is paradoxically characterised not only by coherence, but also by ambiguity. To this the notion of fluidity and constantly shifting priorities and influencing factors can be added, meaning value never assumes invariant shape.

Alternatively, therefore, it might be more appropriate to draw, analogously and figuratively, on the psychedelic animation of a lava lamp. These are characterised by the rising and sinking of amorphous globules, each tirelessly in motion, splitting and reforming in limitless ways. Each observed globule can be imagined as a different unit of value, the relative size and nature of which corresponds to its impact and influence on a constantly morphing aggregation of advantage. As with Rorty’s quilt, the lava lamp is physically constrained in time and space but, as with individual perceptions of value, the prospect it affords is infinitely variable and in constant motion. The rise and fall of the globules represents their shifting status as either benefit or sacrifice in experience, and their collective motion the trading-off of cues for contrasting beliefs. Thus, a consumer may be trading off price against function but, equally, may be trading off values for lifestyles, and lifestyles for identities; or, perhaps, price for identity. And how does one play out against the other? To what extent does, for example, cheap price imply either a frugal commitment to family ideals, or the opportunity to spend elsewhere or, alternatively, a disregard for exploited workers?

Further, as we have already observed, in the same way that there is no clear distinction between benefit and sacrifice, the nature and purpose of each lava lamp globule remains obscure. Likewise, there is no distinction between moral value and overall value; they are inherently conjoined and synchronous within any purchase decision. When all is taken into account, and a purchase is either made or not made, the decision as to whether this represents good value or poor value is made through retrospective justification and the rationalised objectives of the decision. If it contributes to overall perceived personal advantage, then value is positive. If the reverse, then perceived personal disadvantage is the outcome. Returning to our analogy, forces creating the globule ex-ante may be interpreted ex-post differently. Irrespective, the lava inside the lamp would still continuously shift, representing a restless search for ‘endless ends’ and reflecting myriad concerns and issues. Value, constituted as perceived personal advantage, occurs in conscious reflection, but its structure and structuring are constituted in experience. Drawing on ideas initially rehearsed in Woodall et al. (2017), we therefore define perceived personal advantage as:

An aggregate positive or negative consumption-related perception that arises from experience as a result of a complex internal dispute between multiple agendas striving for congruence in overlapping contexts. The perception may relate (either individually, but most likely collectively) to cultural, social or economic capital, and to physical or mental wellbeing. This draws on hybrid conscious/unconscious trade-offs focused on historical and informational cues, and takes place against a backdrop of emergent values; developing sociocultural and economic imperatives; and shifting life-stage/-style objectives.

Our study adds two further dimensions to the debate on ethical consumption. Firstly, that a pragmatist theory of value is an appropriate means to explain the trade-offs that are often claimed to exist. Secondly, that rather than interpreting trade-offs as comprising rational, cognitive or utilitarian valuations, these emerge in practice as a form of consummation which is framed largely as justification after the fact. This is possessed of a single quality that pervades the whole experience, despite variation in its constituent parts (Dewey 2005 [1934]). This unity is expressed in the way we name events and experiences, or in our case, purchases: for example, ‘that’ shirt; ‘that’ coat. And this process of naming, or identifying, is neither distinctively emotional, cognitive nor behavioural, for these labels imply separation of elements within the experience that do not capture its unity.

We also note that for our respondents there was no evidence of an objective ‘best value’ to which ethical concerns might contribute. The multiple identity concerns, values, habits, benefits and sacrifices, and the fuzziness that exists between them develops over time as a result of lived experience and habituation, for which justification is then retrospectively offered. Indeed, as Luedicke et al. (2009) argue, moral narratives can be employed to justify particular status distinctions, regardless of the perceived authenticity of the moral claim. And returning to the original point in this discussion, we see the unified output of consummatory experience to be focused on the pursuit of something better (and/or avoidance of something worse). For the ethically minded consumer, this will incorporate a wish to become an ethical consumer, something incorporated into his/her evoked set of aspirations, represented by ends-in-view, and governed by the pursuit of personal advantage and achievement of preferred modes of identity. Here we agree with Davies and Gutsche (2016) who also found evidence of habitual, self-focused, individualistic and identity-driven consumption activity.

We note though that habits are unlikely to be enduring or fixed. The patterns of behaviour hypothesised from interpretations of consumer narratives are demonstrated in Fig. 2. Here we suggest habits change both in response to new ends-in-view, new identity aims and as different perspectives of advantage arise. These perspectives which, drawing on Dewey (2005 [1934]), might more properly be construed as consummatory perceived personal advantage (PCPA, or disadvantage, PCPD) are focused on an ‘enlightened self-interest’ (Smith 1999) that reconciles agendas for both personal and social objectives. In our account, enlightenment implies altruistic motivation but a focus on individually prescribed ends. As Lundblad and Davies (2016) suggest, it is perfectly possible for the altruistic to feed into the egoistic.

Cycles of consumption will then be repeated as individuals engage in practice, calling prior value judgements into question in response to new reflections on advantage, to life changes, or in justifying beliefs to audiences, and re-engage in practice. Engeström (1999, p. 65) suggests we have “a ‘horizon of possibilities’, which tends to escape once intermediate goals are achieved and so needs to be reconstructed and renegotiated”. Thus, whilst trade-offs are not enacted through purely cognitive and utilitarian decision making, they do take place, and act to consolidate established values and histories and the ideals and futures to which individuals aspire. That is, we find evidence in this context that, as Dewey suggests, in the establishment of ethical mindsets, that trade-offs move beyond the realm of the conscious and into the subconscious, perhaps even reaching down into the unconscious (see Fig. 2).

Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

Although we draw substantive conclusions from our results and believe our interpretations to be sound, we acknowledge that no research can be conducted under ideal conditions or is ever complete. Our aim was to address the experiences of ethically minded consumers by using a category of purchase we believed to be salient to this objective. We sought to obtain a degree of representativeness practical within the confines of methods used, but accept the fallibility of this aim and consequent limitations on generalising our findings. Our interpretation is by necessity, therefore, selective, and we consequently recommend further similar work with different groups and different categories (Memery et al. 2005).

Further we note the centrality of habituation to changes in observed behaviour, and in particular the role of groups and personal history in forming habits for the pragmatic acts of justifying oneself, both to oneself and to an audience. This suggests opportunities for further research in two directions: firstly, developing a better understanding of how communities help shape ethically minded decisions, and secondly, by addressing the role of nostalgia and its possible impact on ethically related behaviour change. The source of the habits described in the thesis could often be traced to childhood, which suggests informants found difficulty ridding themselves of early socialisation effects.

In regard to ethical consumption’s span, we note that studies frequently treat this as an all-encompassing practice which applies across all purchases or behaviours. For example, it might be assumed (either explicitly or implicitly) that a predisposition towards Fair Trade will be enacted across other similarly focused product categories (Low and Davenport 2005; Ma et al. 2012; White et al. 2012). This suggests voluntary simplifiers will adopt complementary practices across all of their consumption activities (Cherrier 2007), or green consumers will behave consistently across all categories (Connolly and Prothero 2008; Lu et al. 2015). The pragmatist view advanced in this paper calls this into question, and further research might seek to explore the extent to which assumed integrative or holistic approaches actually exist and how these might impact personal ends-in-view.

References

Abrantes Ferreira, D., Gonçalves Avila, M., & Dias de Faria, M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and consumers’ perception of price. Social Responsibility Journal, 6(2), 208–221.

Aertsens, J., Verbeke, W., Mondelaers, K., & Van Huylenbroeck, G. (2009). Personal determinants of organic food consumption: A review. British Food Journal, 111(10), 1140–1167.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2000). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research. London: Sage.

Appiah, K. A. (2006). Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a world of strangers. London: Penguin.

Arnould, E. J., & Thompson, C. J. (2005). Consumer culture theory (CCT): Twenty years of research. Journal of Consumer Research., 31(4), 868–882.

Arnould, S. J., & Fischer, E. (1994). Hermeneutics and consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(June), 55–70.

Auger, P., Burke, P., Devinney, T. M., & Louviere, J. J. (2003). What will consumers pay for social product features? Journal of Business Ethics, 42(3), 281–304.

Auger, P., & Devinney, T. M. (2007). Do what consumers say matter? The misalignment of preferences with unconstrained ethical intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 76, 361–383.

Balderjahn, I., Buerke, A., Kirchgeorg, M., Peyer, M., Seegebarth, B., & Wiedmann, K. P. (2013). Consciousness for sustainable consumption: Scale development and new insights in the economic dimension of consumers’ sustainability. AMS Review, 3(4), 181–192.

Bartels, J., & Onwezen, M. C. (2014). Consumers’ willingness to buy products with environmental and ethical claims: The roles of social representations and social identity. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38, 82–89.

Bertman, M. A. (2007). Classical American pragmatism. Penrith: Humanities-EBooks.

Black, I. R., & Cherrier, H. (2010). Anti-consumption as part of living a sustainable lifestyle: Daily practices, contextual motivations and subjective values. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9(6), 437–453.

Bly, S., Gwozdz, W., & Reisch, L. A. (2015). Exit from the high street: An exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(2), 125–135.

Bourdieu, P. (1992). The logic of practice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Boyles, D. R. (2006). Dewey’s epistemology: An argument for warranted assertions, knowing, and meaningful classroom practice. Educational Theory, 56(1), 57–68.

Bray, J., Johns, N., & Kilburn, D. (2011). An exploratory study into the factors impeding ethical consumption. Journal of Business Ethics, 98, 597–608.

Brooks, A. (2015). Clothing poverty: The hidden world of fast fashion and second-hand clothes. London: Zed Books.

Bruner, I. I., Gordon, C., & Pomazal, R. J. (1988). Problem recognition: The crucial first stage of the consumer. The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 5(1), 53–63.

Carpenter, J. M., & Fairhurst, A. (2005). Consumer shopping value, satisfaction, and loyalty for retail apparel brands. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 9(3), 256–269.

Carrigan, M., & Atalla, A. (2001). The myth of the ethical consumer; do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(7), 560–577.

Carrigan, M., Szmigin, I., & Wright, J. (2004). Shopping for a better world? An interpretive study of the potential for ethical consumption within the older market. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 21(6), 401–417.

Carrington, M. J., Neville, B. A., & Whitwell, G. J. (2010). Why ethical consumers don’t walk the talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behavior of ethically minded consumers. Journal of Business Ethics, 97, 139–158.

Carrington, M. J., Neville, B. A., & Whitwell, G. J. (2014). Lost in translation: Exploring the ethical consumer intention–behavior gap. Journal of Business Research, 67(1), 2759–2767.

Carrington, M. J., Zwick, D., & Neville, B. (2016). The ideology of the ethical consumption gap. Marketing Theory, 16(1), 21–38.

Chakrabarti, R., & Mason, K. (2015). Can the pragmatist logic of inquiry inform consumer led market design? In Davies, I. and Silcock, D. (Eds.), Pragmatism and Consumer Research: Advances in Consumer Research (Vol. 43, pp. 215).

Chandler, J. D., & Vargo, S. L. (2011). Contextualization and value-in-context: How context frames exchange. Marketing Theory, 11(1), 35–49.

Chatzidakis, A. (2015). Guilt and ethical choice in consumption: A psychoanalytic perspective. Marketing Theory, 15(1), 79–93.

Cherrier, H. (2005). Using existential-phenomenological interviewing to explore meanings of consumption. In R. Harrison, T. Newholm & D. Shaw, 2005 (ed.). The Ethical Consumer. London: Sage.

Cherrier, H. (2006). Consumer identity and moral obligations in non-plastic bag consumption: A dialectical perspective. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 30(5), 515–523.

Cherrier, H. (2007). Ethical consumption practices: Co-production of self-expression and social recognition. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 6(Sept/Oct), 321–335.