Abstract

Purpose

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive subtype most prevalent among women of Western Sub-Saharan African ancestry. It accounts for 15–25% of African American (AA) breast cancers (BC) and up to 80% of Ghanaian breast cancers, thus contributing to outcome disparities in BC for black women. The aggressive biology of TNBC has been shown to be regulated partially by breast cancer stem cells (BCSC) which mediate tumor recurrence and metastasis and are more abundant in African breast tumors.

Methods

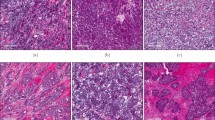

We studied the biological differences between TNBC in women with African ancestry and those of Caucasian women by comparing the gene expression of the BCSC. From low-passage patient derived xenografts (PDX) from Ghanaian (GH), AA, and Caucasian American (CA) TNBCs, we sorted for and sequenced the stem cell populations and analyzed for differential gene enrichment.

Results

In our cohort of TNBC tumors, we observed that the ALDH expressing stem cells display distinct ethnic specific gene expression patterns, with the largest difference existing between the GH and AA ALDH+ cells. Furthermore, the tumors from the women of African ancestry [GH/AA] had ALDH stem cell (SC) enrichment for expression of immune related genes and processes. Among the significantly upregulated genes were CD274 (PD-L1), CXCR9, CXCR10 and IFI27, which could serve as potential drug targets.

Conclusions

Further exploration of the role of immune regulated genes and biological processes in BCSC may offer insight into developing novel approaches to treating TNBC to help ameliorate survival disparities in women with African ancestry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

African Americans

- ALDH:

-

Aldehyde dehydrogenase

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- BCSC:

-

Breast cancer stem cells

- CA:

-

Caucasian Americans

- FACS:

-

Fluorescent activated cell sorting

- GH:

-

Ghanaian

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology Consortium

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- KATH:

-

Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- TNBC:

-

Triple-negative breast cancer

- UM:

-

The University of Michigan

- WSSA:

-

Western sub-Saharan Africans

References

Jiagge E, Chitale D, Newman LA (2018) Triple-negative breast cancer, stem cells, and African ancestry. Am J Pathol 188(2):271–279

Stark A et al (2010) African ancestry and higher prevalence of triple-negative breast cancer: findings from an international study. Cancer 116(21):4926–4932

Schwartz T et al (2013) Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 as a marker of mammary stem cells in benign and malignant breast lesions of Ghanaian women. Cancer 119(3):488–494

Jiagge E et al (2016) Comparative analysis of breast cancer phenotypes in African American, White American, and West versus East African patients: correlation between African ancestry and triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 23:3843–3849

Jiagge E et al (2018) Androgen receptor and ALDH1 expression among internationally diverse patient populations. J Glob Oncol 4:1–8

Jiagge E et al (2016) Breast cancer and African Ancestry: lessons learned at the 10-year anniversary of the Ghana-Michigan Research Partnership and International Breast Registry. J Glob Oncol 2(5):302–310

Newman LA et al (2006) Meta-analysis of survival in African American and white American patients with breast cancer: ethnicity compared with socioeconomic status. J Clin Oncol 24(9):1342–1349

Newman LA et al (2019) Hereditary susceptibility for triple negative breast cancer associated with Western Sub-Saharan African ancestry: results from an International Surgical Breast Cancer Collaborative. Ann Surg 270(3):484–492

Carey LA et al (2007) The triple negative paradox: primary tumor chemosensitivity of breast cancer subtypes. Clin Cancer Res 13(8):2329–2334

Carey LA et al (2006) Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA 295(21):2492–2502

Charafe-Jauffret E et al (2009) Breast cancer cell lines contain functional cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity and a distinct molecular signature. Cancer Res 69(4):1302–1313

Dontu G et al (2003) In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev 17(10):1253–1270

Ginestier C et al (2007) ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell 1(5):555–567

Nalwoga H et al (2010) Expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) is associated with basal-like markers and features of aggressive tumours in African breast cancer. Br J Cancer 102(2):369–375

Dave B, Chang J (2009) Treatment resistance in stem cells and breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 14(1):79–82

Li X et al (2008) Intrinsic resistance of tumorigenic breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 100(9):672–679

Al-Hajj M et al (2003) Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100(7):3983–3988

Perrone G et al (2012) In situ identification of CD44+/CD24- cancer cells in primary human breast carcinomas. PLoS One 7(9):e43110

Fitzgibbons et al (2013) Template for reporting results of biomarker testing of specimens from patients with carcinoma of the breast. Am Coll Pathologists 138(5):595–601

Draghici S et al (2007) A systems biology approach for pathway level analysis. Genome Res 17(10):1537–1545

Tarca AL et al (2009) A novel signaling pathway impact analysis. Bioinformatics 25(1):75–82

Alexa A, Rahnenfuhrer J, Lengauer T (2006) Improved scoring of functional groups from gene expression data by decorrelating GO graph structure. Bioinformatics 22(13):1600–1607

Szklarczyk D et al (2017) The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein–protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res 45(D1):D362–D368

Ding L et al (2010) Genome remodelling in a basal-like breast cancer metastasis and xenograft. Nature 464(7291):999–1005

du Manoir S et al (2014) Breast tumor PDXs are genetically plastic and correspond to a subset of aggressive cancers prone to relapse. Mol Oncol 8(2):431–443

Kobayashi H et al (2013) Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility genes (review). Oncol Rep 30(3):1019–1029

Coles C et al (1992) p53 mutations in breast cancer. Cancer Res 52(19):5291–5298

Witton CJ et al (2003) Expression of the HER1-4 family of receptor tyrosine kinases in breast cancer. J Pathol 200(3):290–297

Yu LY et al (2017) New immunotherapy strategies in breast cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(1):68

Mittendorf EA et al (2014) PD-L1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2(4):361–370

Jafarzadeh A et al (2016) Higher circulating levels of chemokine CXCL10 in patients with breast cancer: evaluation of the influences of tumor stage and chemokine gene polymorphism. Cancer Biomark 16(4):545–554

Hendrickx W et al (2017) Identification of genetic determinants of breast cancer immune phenotypes by integrative genome-scale analysis. Oncoimmunology 6(2):e1253654

Jiagge E et al (2016) Comparative analysis of breast cancer phenotypes in African American, White American, and West versus East African patients: correlation between African ancestry and triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 23(12):3843–3849

Bryc K et al (2015) The genetic ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. Am J Hum Genet 96(1):37–53

Klemm F, Joyce JA (2015) Microenvironmental regulation of therapeutic response in cancer. Trends Cell Biol 25(4):198–213

Fulton A et al (2006) Prospects of controlling breast cancer metastasis by immune intervention. Breast Dis 26:115–127

Ejaeidi AA et al (2015) Hormone receptor-independent CXCL10 production is associated with the regulation of cellular factors linked to breast cancer progression and metastasis. Exp Mol Pathol 99(1):163–172

Planes-Laine G, Rochigneux P, Bertucci F et al (2019) PD-1/PD-L1 targeting in breast cancer: the first clinical evidences are emerging. A literature review. Cancers (Basel) 11(7):1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11071033

Yuan C, Liu Z, Yu Q, Wang X, Bian M, Yu Z, Yu J (2019) Expression of PD-1/PD-L1 in primary breast tumours and metastatic axillary lymph nodes and its correlation with clinicopathological parameters. Sci Rep 9(1):14356. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50898-3

Coban C et al (2005) Toll-like receptor 9 mediates innate immune activation by the malaria pigment hemozoin. J Exp Med 201(1):19–25

Dobrolecki LE, Airhart SD, Alferez DG, Aparicio S, Behbod F, Bentires-Alj M, Brisken C, Bult CJ, Cai S, Clarke RB, Dowst H, Ellis MJ, Gonzalez-Suarez E, Iggo RD, Kabos P, Li S, Lindeman GJ, Marangoni E, McCoy A, Meric-Bernstam F, Lewis MT (2016) Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models in basic and translational breast cancer research. Cancer Metastasis Rev 35(4):547–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-016-9653-x

Dominguez TP, Strong EF, Krieger N, Gillman MW, Rich-Edwards JW (2009) Differences in the self-reported racism experiences of US-born and foreign-born Black pregnant women. Soc Sci Med 69(2):258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.022

Acknowledgements

Work supported in part by the Komen for the Cure Promise grant (LN, MW, JC), the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (MW, SDM), the Metavivor Foundation (SDM), the Rackham Barbour Scholarship, UM Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA 046592, and the ULAM In Vivo Animal Core histopathology laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jiagge, E.M., Ulintz, P.J., Wong, S. et al. Multiethnic PDX models predict a possible immune signature associated with TNBC of African ancestry. Breast Cancer Res Treat 186, 391–401 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06097-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06097-8