Abstract

Prior research provides mixed evidence regarding the direction of the association between sexual and marital satisfaction. Whereas some studies suggest a bidirectional association, other studies fail to document one direction or the other. The current investigation used a 12-day diary study of 287 married individuals to clarify the nature of this association. Results from time-lagged mixed modeling revealed a significant positive bidirectional association. Both higher global sexual satisfaction one day and satisfaction with sex that occurred that day predicted higher marital satisfaction the next day; likewise, higher marital satisfaction one day significantly predicted higher global sexual satisfaction the next day and higher satisfaction with sex that occurred the next day. Both associations remained significant after controlling for participant’s gender/sex, neuroticism, attachment insecurity, self-esteem, stress, perceived childhood unpredictability and harshness, age of first intercourse, construal level, age, and length of marriage. We also explored whether these covariates moderated either direction of the association. Daily stress was the most reliable moderator, with three of the four interactions tested remaining significant after Bonferroni corrections. The bidirectional association between global sexual and marital satisfaction and the positive association between satisfaction with sex that occurred that day and marital satisfaction the next day were significantly stronger when individuals experienced high versus low stress. Although the exploratory nature of all moderation analyses suggests they should be replicated before drawing strong conclusions, these findings highlight the importance of sexual satisfaction to marital satisfaction and vice versa and point to the power of stress in strengthening these associations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sexual and relationship satisfaction are clearly associated (for reviews, see Maxwell & McNulty, 2019; Muise et al., 2016), but the exact nature of this association is less clear. Specifically, it remains unclear whether (a) sexual satisfaction leads to relationship satisfaction, (b) relationship satisfaction leads to sexual satisfaction, (c) both directional associations exist, or (d) neither directional association exists because a third variable accounts for the positive association.

Theories and Evidence Suggesting a Bidirectional Association Between Sexual and Relationship Satisfaction

Interdependence theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978) can be used to argue that sexual satisfaction leads to relationship satisfaction. According to this theory, people base their overall satisfaction with a relationship on (a) the extent to which their relationship rewards outweigh their relationship costs and (b) how those rewards and costs compare to their own individual standards, such as the personal importance of these rewards and costs (see Fletcher et al., 1999). Given that people tend to consider satisfying sex as a relationship reward (Arriaga, 2013), interdependence theory suggests that, all else being equal, a satisfying sexual relationship should lead to higher relationship satisfaction.

There is some empirical support for this directional association (for reviews, see Maxwell & McNulty, 2019; Muise et al., 2016). First, sexual functioning plays an integral role in determining how several important risk factors are associated with relationship satisfaction. For example, higher neuroticism (Fisher & McNulty, 2008) and poorer body image (Meltzer & McNulty, 2010) can contribute to lower relationship satisfaction through lower sexual satisfaction. Moreover, having a strong sexual relationship can buffer against the negative impacts of both neuroticism (Russell & McNulty, 2011) and attachment insecurity (Little et al., 2010) on relationship satisfaction. Second, several longitudinal studies have shown that sexual satisfaction at baseline predicts relationship satisfaction at a later assessment (Cao et al., 2019 found this for husbands only; Fallis et al., 2016; McNulty et al., 2016; Quinn-Nilas, 2020; Sprecher, 2002; Yeh et al., 2006). In one study, for example, McNulty et al. (2016) pooled the data from two longitudinal studies of newlywed couples, both of which assessed sexual and marital satisfaction eight times across four years, to show that sexual satisfaction at one assessment predicted marital satisfaction at the next assessment, controlling for marital satisfaction at the prior assessment.

At the same time, there is also reason to expect that having a satisfying relationship can lead to a higher sexual satisfaction. Lawrance & Byers (1995) applied the tenets of interdependence theory to develop the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction (IEMSS), which posits that individuals base their sexual satisfaction on (a) the extent to which their sexual rewards outweigh their sexual costs and (b) how those sexual rewards and costs compare to their personal sexual standards. Yet, in addition to offering evidence for this idea, Lawrance & Byers (1995) showed that participants’ relationship satisfaction uniquely predicted their sexual satisfaction independent of their sexual rewards and costs. Such findings make sense from other theoretical perspectives: not only may specific qualities of a happy relationship (e.g., intimacy, self-disclosure) lead to more satisfying sexual functioning, evaluative processes such as the halo effect (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977) and sentiment override (Weiss, 1980) suggest that generally positive evaluations of the whole (i.e., the relationship) guide evaluations of the components of that whole (i.e., the sexual relationship). Indeed, based on their findings, Lawrance & Byers (1995) went on to conclude that, “In all likelihood, the relationship between sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction is dynamic, with each reciprocally influencing the other” (p. 282). Consistent with this idea, some of the same studies demonstrating that sexual satisfaction predicts changes in relationship satisfaction (Cao et al., 2019; McNulty et al., 2016; Quinn-Nilas, 2020), along with one other (Vowels & Mark, 2020), have also revealed that relationship satisfaction predicts changes in sexual satisfaction. In addition to showing that initial sexual satisfaction predicted subsequent marital satisfaction, for instance, McNulty et al. (2016) demonstrated that initial marital satisfaction predicted subsequent sexual satisfaction.

Mixed Findings and Limits to Existing Research

Nonetheless, several studies have failed to find support for at least one of the two directional associations (Byers, 2005; Cao et al., 2019; Fallis et al., 2016; Sprecher, 2002; Vowels & Mark, 2020; Yeh et al., 2006). For instance, a two-wave study across 18 months and a dyadic five-wave study across four years both failed to offer longitudinal evidence of either directional association (Byers, 2005; Sprecher, 2002). They revealed a nonsignificant association between (a) relationship satisfaction at Time 1 and changes in sexual satisfaction from Time 1 to Time 2 and (b) sexual satisfaction at Time 1 and changes in relationship satisfaction from Time 1 to Time 2. Likewise, an independent five-wave study of married couples found a nonsignificant association between relationship satisfaction and subsequent sexual satisfaction (Yeh et al., 2006), and a three-wave study of couples found that sexual satisfaction failed to significantly predict changes in relationship satisfaction (Vowels & Mark, 2020). The last study further revealed weak and inconsistent associations between initial relationship satisfaction and subsequent sexual satisfaction such that a trending negative association emerged among women, whereas a significant positive association emerged among men. Furthermore, two-wave study across one year of couples revealed that relationship satisfaction did not significantly predict changes in sexual satisfaction, although sexual satisfaction significantly predicted later relationship satisfaction, and more strongly so for men than women (Fallis et al., 2016). Finally, a three-wave study across two years of Chinese couples in early marriage found a nonsignificant association between marital satisfaction and subsequent sexual satisfaction for husbands, as well as a nonsignificant association between sexual satisfaction and subsequent marital satisfaction for wives (Cao et al., 2019).

Before disregarding the idea that the association between sexual and relationship satisfaction is bidirectional, however, it is important to consider alternative explanations for these nonsignificant findings. One explanation is that most studies have used long assessment intervals, ranging from six months between assessments (McNulty et al., 2016; Sprecher, 2002) to 18 months between assessments (Byers, 2005; Cao et al., 2019; Yeh et al., 2006) to 10 years between assessments (Quinn-Nilas, 2020). Although several of these studies provided evidence for at least one directional association, longer time frames allow both the predictor and outcome to change multiple times between assessments due to other influences, which could render the detection of a bidirectional association more difficult. Using shorter assessment windows could help minimize the opportunity for such intervening changes to obscure a bidirectional association. Indeed, daily diary studies have revealed important findings for relationship and sexual functioning (e.g., Impett et al., 2012; Raposo & Muise, 2021; Rubin & Campbell, 2012). Of course, it is also possible that one or both directions of the bidirectional association take time to manifest, in which case a daily diary study may offer no evidence for a bidirectional association. Given this range of possibilities, and given we are aware of no studies investigating the bidirectional association between sexual and relationship satisfaction using daily measurements, the current investigation fills this gap using a 12-day diary study.

Potential Moderators

An additional reason for mixed evidence of the bidirectional association between sexual and relationship satisfaction is that there may be important yet overlooked moderators for one or both directions of the association. Both interdependence theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959) and IEMSS (Lawrance & Byers, 1995) suggest that the impact of rewards and costs on each type of evaluation depends on how important a particular quality is to the individual evaluating. Because individuals evaluate their relationships by considering the rewards and costs of the relationship (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959), sexual satisfaction should be most likely to predict relationship satisfaction for those who highly value sex. Likewise, the extent to which individuals evaluate their sex life by considering the rewards and costs of their general relationship should depend on how personally important relationship satisfaction is as a determinant of sexual satisfaction. Thus, in addition to examining the bidirectional association between sexual and relationship satisfaction, we also explored individual differences and external circumstances (see Karney & Bradbury, 1995) that may lead individuals to differentially weigh these sexual and relationship satisfaction in their evaluations. Specifically, we considered gender/sex, neuroticism, attachment insecurity, self-esteem, acute stress, childhood ecology, age at first intercourse, construal level, age, and length of marriage.

Gender/Sex

Regarding gender/sex, prior research has provided mixed evidence for differences in these associations. Several lines of research suggest that sexual gratification is more important to men/males than women/females (Ellis & Symons, 1990; Fletcher et al., 1999; Peplau, 2003), which suggests that sexual satisfaction may more strongly influence relationship satisfaction among men/males and compared to women/females. Indeed, some studies have revealed a stronger association between sexual satisfaction and subsequent relationship satisfaction for men than women (Cao et al., 2019; Fallis et al., 2016; Kisler & Christopher, 2008; McNulty et al., 2016; Peck et al., 2004; Sánchez-Fuentes & Santos-Iglesias, 2016; Sprecher, 2002). At the same time, other perspectives suggest women/females rely more heavily on contextual factors when evaluating their sexual experiences (Baumeister, 2000; Diamond, 2003), which suggests relationship satisfaction may more strongly impact sexual satisfaction among women/females compared to men/males.

Neuroticism and Attachment Insecurity

Both neuroticism and attachment insecurity have been linked to sexual and relationship satisfaction (e.g., Birnbaum, 2007; Karney & Bradbury, 1997; Russell & McNulty, 2011). Given that neuroticism involves a tendency to show strong emotional reactions to interpersonal experiences in general (Bolger & Schilling, 1991), individuals higher (versus lower) in neuroticism may more strongly generalize feelings about one aspect of the relationship to another, which may strengthen either direction of the association between sexual and relationship satisfaction. On the other hand, attachment anxiety involves a strong desire to enhance intimacy (Schachner & Shaver, 2004), which suggests that individuals higher (versus lower) in attachment anxiety may place a higher value on their feelings of sexual satisfaction when evaluating their relationships. In contrast, attachment avoidance involves a tendency to engage in sexual activities in a less intimate context (Butzer & Campbell, 2008), and thus, sexual and relationship satisfaction may predict each other to a lesser extent among individuals higher (versus lower) in attachment avoidance.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is another individual difference that has been directly tied to both sexual and relationship satisfaction (e.g., Larson et al., 1998; Schaffhuser et al., 2014; Weidmann et al., 2017). Self-esteem guides emotional reactions, such that individuals with lower self-esteem have more negative emotional reactions to evaluative feedback (Dutton & Brown, 1997). If self-esteem also guides emotional reactions to specific relationship experiences, then individuals with lower self-esteem may have more negative reactions to unpleasant sexual interactions with their partners, and which may influence their overall perceptions of the relationship (Forgas, 1994a, 1994b). For this reason, individuals with lower (versus higher) self-esteem may experience a stronger impact of sexual satisfaction on relationship satisfaction.

Stress

Acute stress due to circumstances occurring outside the relationship is associated with increased cognitive load and therefore decreased self-regulatory capacity (for a review, see Hofmann et al., 2012; Schoofs et al., 2008). Given that individuals under cognitive load tend to rely on mental shortcuts for evaluations (Allred et al., 2016; Roch et al., 2000; Schneider et al., 2012), individuals experiencing higher (versus lower) stress when evaluating one aspect of their relationship may rely more on evaluations previously made in another domain. Importantly, this general tendency may not apply specifically to one direction of the association: individuals experiencing higher stress while forming overall evaluations of the relationship may rely more heavily on previous evaluations of their sexual relationship, and individuals experiencing higher stress while forming evaluations of their sexual relationship may rely more heavily on previous evaluations of their overall relationship.

Developmental History

Life history theory outlines how individual differences in the harshness and unpredictability of childhood ecologies promote different reproductive strategies (Belsky et al., 2012; Brumbach et al., 2009). Given that harsh and unpredictable childhood environments risk earlier mortality, individuals reared in such environments typically adopt “fast” reproductive strategies that prioritize reproduction over personal growth. In contrast, given that safe and predictable childhood environments allow for greater longevity, individuals reared in such environments typically adopt “slow” reproductive strategies that prioritize personal growth and resource acquisition over reproduction. Providing support for life history theory, individuals reared in harsh and unpredictable environments experience early sexual maturity (Golden et al., 2016; Woo & Brotto, 2008), which is linked to higher sexual satisfaction (Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 1997; Pedersen & Blekesaune, 2003), and the tendency to prioritize sex over commitment (Szepsenwol et al., 2017). Given their prioritization of reproductive goals, individuals with a fast (versus slow) life strategy who have experienced any of the following—a harsh and unpredictable childhood ecology, or an early sexual debut—may draw more strongly from evaluations of their sexual relationship when evaluating their overall relationship.

Construal Level

Construal level theory (Trope & Liberman, 2010) outlines the implications of individual differences in a tendency to construe experiences in an abstract versus concrete manner. An abstract construal focuses on central, decontextualized, and global features in the target of evaluation, whereas a concrete construal focuses on peripheral, context-dependent, and specific features. In the case of relationship and sexual evaluations, sexual experiences are specific components of the overall relationship, and thus, individuals with a more concrete (versus abstract) construal may draw more strongly from specific occurrences of sex when evaluating subsequent relationship satisfaction. Individuals with a more abstract (versus concrete) construal, in contrast, may draw more strongly from global quality of the relationship when subsequently evaluating the more specific sexual experiences in their relationship.

Age and Length of Relationship

Lastly, sexual desire or functioning can decline with both age (DeLamater & Sill, 2005; Laumann & Waite, 2008; Mitchell et al., 2013) and relationship length (Baumeister & Bratslavsky, 1999). Given that individuals tend to devalue aspects of the relationship that are less fulfilling (Neff & Karney, 2003), sex may play a less important role in the relationships of people who are older and who have been married a for longer duration. Accordingly, sexual satisfaction may less strongly predict relationship satisfaction among people who are older (versus younger) or in more (versus less) established relationships.

Current Investigation

The present study had two aims. Aim One was to conceptually replicate prior findings supporting a bidirectional, time-lagged association between sexual and marital satisfaction with a daily-diary design, while controlling for potential third variables. We predicted that sexual satisfaction one day would predict marital satisfaction the next day and marital satisfaction one day would predict sexual satisfaction the next day. Aim Two was to explore potential moderators of one or both directions of this bidirectional association: gender/sex, neuroticism, attachment insecurity, self-esteem, stress, developmental history, construal level, age, and length of marriage. Given the exploratory nature of Aim Two and the multiple tests conducted, we used Bonferroni corrections to minimize Type I errors.

Method

Participants

Participants were married individuals (N = 287) recruited for a broader study examining the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on families in the summer of 2020 from Prolific.co. Prolific is an online survey platform where participants are guaranteed a minimum wage for their time completing studies. Prior research suggests that Prolific users are typically more naïve about commonly used research goals and measures, less dishonest, and provide higher quality data compared to samples of other web-based data collection platforms (e.g., Amazon’s Mechanical TURK; Peer et al., 2017). In this study, we only recruited participants who were married, currently living in the US or the UK, willing to record a video as part of the study, and had access to a laptop or desktop running either Mac or Windows 10 or higher. The latter two criteria were for parts of the study outside the scope of the current investigation.

The sample was more diverse than many existing marital studies (Williamson et al., 2022)—63.1% self-identified as Caucasian, 10% as Asian, 4.8% as Mixed, and 3.7% as Black. One hundred and six participants reported being male and 104 of them identified as men; one identified as a woman and the other identified as nonbinary. One hundred and eighty-one participants reported being female and 180 of them identified as women; one remaining female identified as nonbinary. Most (96.2%) of the participants reported being in a heterosexual relationship. Among the participants who responded, 84.4% indicated they were in their first marriage; 61.0% of the participants reported having no children. Among those with children, the median number of children was two and the mean age of the children was 11.95 years (SD = 9.79). On average, the participants were 38.73 years of age (SD = 9.83), had been married for 9.09 years (SD = 8.97), completed 8.94 years of education since the beginning of high school (SD = 2.59), and independently earned US$45,401.60 before tax in the previous year. Participants were compensated with US$40 for their time and participation.

Procedure

Prior to participation, we informed participants that the purpose of the current investigation was to examine the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on families. Upon passing our eligibility check and consenting to participation, participants completed a baseline questionnaire that included demographic items and measures of all moderators and covariates except for stress. The baseline session also involved other tasks beyond the scope of the reported analyses, including implicit measures, a problem-solving discussion, and questions about individual differences, relationship experiences, parenting, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Then, on each of the following 12 days, participants completed a diary survey that included items assessing marital and sexual satisfaction, whether they engaged in sex that day and how satisfied they were with any sex that occurred that day, stress, and other items beyond the scope of the current analyses such as personal well-being, daily relationship processes, and experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Measures

Demographics

We collected participants’ biological sex at baseline along with other demographic information such as gender, age, race, education, income, number of marriages, as well as the number and age of children (if any). We used biological sex instead of gender as a moderator because all participants identified a binary biological sex, but this was not the case for gender. Nevertheless, given the important potential differences between biological sex and gender identification, we also report analyses using gender. We refer to the biological sex variable examined here as gender/sex.

Daily Marital Satisfaction

Each day, participants completed the three-item Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale (Schumm et al., 1983) to indicate their daily marital satisfaction. Using a seven-point Likert scale from 1 = “Not at all satisfied” to 7 = “Extremely satisfied,” participants reported their satisfaction with their (a) partners, (b) relationships with their partners, and (c) marriages. We summed across these items to form a daily index of marital satisfaction, with possible scores ranging from 3 to 21. Internal consistency was high on all days (αday1 = 0.97, αday2 = 0.96, αday3 = 0.97, αday4 = 0.97, αday5 = 0.97, αday6 = 0.97, αday7 = 0.97, αday8 = 0.96, αday9 = 0.98, αday10 = 0.95, αda11 = 0.97, αday12 = 0.96).

Daily Global Sexual Satisfaction

Each day, participants also reported their global sexual satisfaction with a single-item asking, “In reflecting upon your day as a whole, how satisfied were you with your sex life today?” Participants responded using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Not at all” to 7 = “Extremely.” Prior daily-diary studies (e.g., Dobson et al., 2020; Impett et al., 2012; Little et al., 2010) and psychometric research (e.g., Bergkvist & Rossiter, 2007; Elo et al., 2003; Milton et al., 2011) attest to the reliability and validity in similar single-item measures.

Satisfaction with Sex that Occurred that Day

In addition to examining the broad association between sexual and marital satisfaction, the daily nature of this study allowed us to assess satisfaction with specific acts of sex when they occurred and thus examine whether satisfaction with sex that occurred on a given day was associated with marital satisfaction the prior or following day. Specifically, participants were asked if they had sex with their partner that day and, and if so, their satisfaction with that occurrence of sex using the following item: “How satisfied were you with the sex?” where 1 = “Not at all satisfied” and 7 = “Very satisfied.”

Neuroticism

In the current investigation, we assessed neuroticism at baseline using the emotional stability subscale of the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (Gosling et al., 2003). Participants responded to two relevant items assessing the extent to which they saw themselves as “anxious, easily upset” and “calm, emotionally stable” (reverse-coded), using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Disagree strongly” to 7 = “Agree strongly.” We averaged across these two items such that higher scores indicated higher levels of neuroticism. Internal consistency was acceptable (α = 0.76).

Attachment Insecurity

We assessed attachment insecurity at baseline using the Adult Attachment Questionnaire (Simpson et al., 1996). Participants responded to 17 items assessing attachment anxiety and avoidance, such as “Others often are reluctant to get as close as I would like” and “I find it difficult to trust others completely,” using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “I strongly disagree” to 7 = “I strongly agree.” We averaged across these items such that higher scores indicated higher levels of attachment anxiety or avoidance. Internal consistency was adequate (for attachment anxiety, α = 0.81, for attachment avoidance, α = 0.85).

Self-Esteem

We assessed self-esteem at baseline with the 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965). Participants responded to a list of statements assessing their general feelings about themselves, such as “I feel that I have a number of good qualities” and “I feel that I'm a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others,” using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 4 = “Strongly agree.” After reverse-coding the appropriate items, we created a sum score across all items, with a higher score indicating higher levels of self-esteem. Internal consistency was high (α = 0.92).

Daily Stress

We measured daily stress using a single-item question assessing the extent to which participants felt stressed that day. Participants responded on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Not at all” to 7 = “A lot.”

Developmental History

We assessed three variables associated with participants’ developmental history. As has been done in prior research (Aronoff & DeCaro, 2019; Simpson et al., 2012), we assessed childhood harshness at baseline using the one-item MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (Adler et al., 2000) specifically focusing on childhood. Participants viewed a picture of a ladder, and we told them to think of the ladder as representing where people stand in society such that “At the top of the ladder are the people who are the best off—those who have the most money, the most education, and the most respected jobs. At the bottom are the people who are the worst off—who have the least money, least education, and the least respected jobs or no job. The higher up you are on this ladder, the closer you are to the people at the very top; the lower you are, the closer you are to the people at the very bottom.” Participants indicated their family’s standing on the ladder from 1 to 10, such that higher scores indicated higher self-perceived family status, and therefore lower childhood harshness.

As has also been done in prior research (Szepsenwol et al., 2015), we assessed childhood unpredictability at baseline using three single-item questions measuring the unpredictability of their early childhood environment. These items were: “In your early childhood, did your parents or legal guardians change jobs or occupational status?,” “In your early childhood, were there changes to your place of residence?,” and “In your early childhood, were there changes in your familial circumstances (divorce or separation of parents, parents starting new romantic relationships, parents leaving the home, etc.)?” Participants responded to each item using a Likert scale from 1 = “Never” to 7 = “Many times.” We averaged across these three items to form an index of childhood unpredictability, with higher scores indicating greater childhood unpredictability. Internal consistency was lower than desired (α = 0.57).

Finally, as has been done in prior research (Dishion et al., 2012; Segal & Stohs, 2009; Vigil, 2005), we assessed whether participants appeared to adopt a “fast” or “slow” reproductive strategy by measuring their age at first sexual intercourse using a single item free-response question stating, “How old were you when you had sexual intercourse for the first time?” Responses were content validated for numerical values only, with a younger age indicating a faster reproductive strategy.

Construal Level

We assessed construal level at baseline using a 10-item version of the Behavioral Identification Form (Slepian et al., 2015; Vallacher & Wegner, 1989). Participants received instructions to choose between a concrete and an abstract interpretation of a list of behaviors, such as “Voting: influencing the election OR marking a ballot” and “Picking an apple: getting something to eat OR pulling an apple off a branch.” We coded responses such that 0 = concrete construal and 1 = abstract construal, and then averaged across them to form an index of construal level. A higher score indicated a more abstract construal. Internal consistency was lower than desired (α = 0.67).

Results

A total of 287 participants collectively completed 2812 diary entries across 12 days. The median number of diaries completed was 12. Overall, 155 participants completed all 12 diary entries, and 207 participants completed at least 10 entries. We tested a time-lagged mixed model of between- and within-person variance in marital and sexual satisfaction across 12 days using SPSS Version 24. We transformed all variables except for gender/sex, age, age at first intercourse, and length of marriage into z-scores prior to analyses to aid in interpretation and comparison of effects. We centered day, age, age at first intercourse, and length of marriage around the sample mean to aid in interpretation of any effects in terms of time.

Prior to testing the proposed bidirectional association, we examined the amount of within-person variance in daily marital satisfaction, daily global sexual satisfaction, and satisfaction with sex that occurred that day by calculating their interclass correlation coefficients (ICCs). The ICC represents the proportion of total variance that is within-person, where higher scores indicate a higher within-person correlation, and thus a lower proportion of within-person variance. The standard deviations were 0.57 for daily marital satisfaction, 0.64 for daily global sexual satisfaction, and 0.51 for satisfaction with sex that occurred that day. The ICCs were 0.54, 0.63, 0.50, respectively. In other words, approximately half the variability in marital satisfaction and satisfaction with sex that occurred that day was between participants, whereas the other half was within participants. For daily global sexual satisfaction, about 60% of the variance was between participants, whereas 40% was within participants.

These ICCs also offer insight into the additional power gained by our repeated reports. Specifically, we used the following formula provided by Snijders & Bosker (2011) to compute the effective sample size for daily marital satisfaction, daily global sexual satisfaction, and satisfaction with sex that occurred that day:

Our effective sample sizes for these three key measures were 487, 429, and 393, respectively, and they each afforded us 0.80 power to detect an effect-size r as small as 0.13, 0.13, and 0.14, respectively.

Bidirectional Association between Sexual and Marital Satisfaction

We next tested our primary analyses. To examine whether daily global sexual satisfaction or satisfaction with sex that occurred that day predicted marital satisfaction the next day, we estimated two time-lagged mixed models that regressed marital satisfaction on day n + 1 onto either daily global sexual satisfaction or satisfaction with sex that occurred on day n, controlling for time and marital satisfaction on day n. We estimated these models with and without all covariates, where daily stress was the stress reported on the same day that the sexual evaluation was reported to control for shared variance between stress and the key predictor. In both models, we estimated a random intercept and slope for same-day marital satisfaction, using a variance component covariance matrix. Model testing that compared the fit of various random effects and covariance structures indicated this was the best fitting model. Results appear in the top half of Table 1. Consistent with predictions and prior research (Fallis et al., 2016; McNulty et al., 2016; Quinn-Nilas, 2020; Yeh et al., 2006), higher daily global sexual satisfaction and higher satisfaction with sex that occurred on one day predicted higher marital satisfaction the next day. Both effects were significant with and without covariates.

To examine whether marital satisfaction on one day predicted global sexual satisfaction or satisfaction with sex that occurred the next day, we estimated two multilevel models regressing either global sexual satisfaction or satisfaction with sex that occurred on day n + 1 onto marital satisfaction on day n, controlling for time and either global sexual satisfaction or satisfaction with sex that occurred on day n. We again estimated these models with and without all covariates, where daily stress was the stress reported on the same day that marital satisfaction was reported to control for shared variance between stress and the key predictor. In the model with daily global sexual satisfaction, we estimated a random intercept and slope for same-day sexual and marital satisfaction, using a variance component covariance matrix; in the model with satisfaction with sex that occurred that day, we estimated a random slope for same-day satisfaction with sex that occurred that day only, using an identity covariance matrix. Model testing that compared the fit of various random effects and covariance structures indicated these were the best fitting models. Results appear in bottom half of Table 1. Consistent with predictions and prior research (McNulty et al., 2016; Quinn-Nilas, 2020; Vowels & Mark, 2020), higher marital satisfaction on one day predicted higher global sexual satisfaction and satisfaction with sex that occurred the next day with and without covariates.

Moderators of the Bidirectional Association

Finally, we explored whether each variable moderated either direction of the association between daily sexual and marital satisfaction by entering each moderator and interaction term into the models specified above. To avoid overfitting the models, we examined each moderator in a separate model, with the exceptions being attachment anxiety and avoidance in the same model, and childhood harshness, and childhood unpredictability, and age at first intercourse in the same model. Given that we expected stress to play a role because stress increases cognitive load (Schoofs et al., 2008), thereby leading people to rely on mental shortcuts for evaluations (Allred et al., 2016; Roch et al., 2000; Schneider et al., 2012), we used reports of stress that were provided on the same day as the outcome variable (i.e., stress on day n + 1). Further, we isolated the two different sources of variance in reports of stress by centering daily reports on their means and entering both the between-person means and person-centered scores as simultaneous moderators. This allowed us to determine if one or both sources of variance moderated either directional association (see Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). Because we conducted multiple moderation models without strong predictions, we used Bonferroni corrections to reduce the chance of Type I error. We explored 12 moderators; hence, the correction reduced the significance level to 0.0042. However, it is important to note that Bonferroni adjustments have been criticized for being too conservative and increasing Type II error rates (Bender & Lange, 2001; Perneger, 1998; Wright, 1992), particularly when the number of tests is larger than five (Bender & Lange, 2001), as is the case here. We therefore decomposed any interactive effects that were near this cutoff. To be clear, we do not claim such effects as meaningful, but we do want to inform readers of the pattern in such interactions to allow for potential replication.

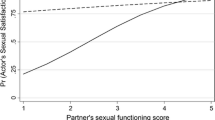

Results of exploratory analyses involving daily global sexual satisfaction appear in Table 2, and results of exploratory analyses involving satisfaction with sex that occurred that day appear in Table 3. Only person-centered daily stress demonstrated robust evidence of moderation, with three of the four interactions remaining significant after Bonferroni corrections (see Fig. 1). We decomposed all three significant interactions by conducting simple effect tests of the association between sexual and marital satisfaction at high and low (± 1 SD) levels of person-centered next-day stress. Global sexual satisfaction on one day predicted marital satisfaction the next day when stress the next day was higher than normal, b = 0.13, SE = 0.03, t(2313) = 4.96, p < 0.001, but not when stress was lower than normal, b = −0.04, SE = 0.03, t(2303) = -1.47, p = 0.141; likewise, marital satisfaction on one day predicted global sexual satisfaction the next day when stress the next day was higher than normal, b = 0.12, SE = 0.03, t(259) = 4.55, p < 0.001, but not when stress was lower than normal, b = 0.01, SE = 0.03, t(320) = 0.46, p = 0.645; lastly, satisfaction with sex that occurred that day more strongly predicted marital satisfaction the next day when stress the next day was higher than normal, b = 0.27, SE = 0.05, t(523) = 5.78, p < 0.001, compared to when stress was lower than normal, b = 0.10, SE = 0.05, t(525) = 2.17, p = 0.030. We decomposed three additional interactions close to significance after Bonferroni corrections in the Supplemental Materials.

Significant Interactions between Daily Stress and the Association between Global Sexual Satisfaction and Marital Satisfaction Panel a. Daily global sexual satisfaction interacts with next-day stress to predict next-day marital satisfaction. Panel b. Daily marital satisfaction interacts with next-day stress to predict next-day global sexual satisfaction. Panel c. Satisfaction with sex that occurred that day interacts with next-day stress to predicit next-day marital satisfaction. Note. All variables except for days were transformed into z-scores prior to analyses. Daily stress was person-centered prior to transforming, and day was centered around the sample mean

Discussion

The current investigation used a 12-day diary design and revealed a bidirectional association between daily evaluations of the sexual and marital relationship, conceptually replicating similar patterns uncovered by previous longitudinal research (Lawrance & Byers, 1995; McNulty et al., 2016; Quinn-Nilas, 2020), while extending them to the daily level. Evaluations of the sexual relationship on one day predicted evaluations of the marital relationship the next day, and evaluations of the marital relationship on one day predicted evaluations of the sexual relationship the next day. This bidirectional association emerged using two different measures of sexual satisfaction—a measure of daily global sexual satisfaction and a measure of satisfaction with sex that occurred that day. It also remained significant even after controlling for participants’ gender/sex, neuroticism, attachment insecurity, self-esteem, daily stress, perceived childhood harshness and unpredictability, age at first intercourse, construal level, age, and length of marriage.

Theoretical Implications

These findings offer important insight into processes of relationship development, and lend further support to both interdependence theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959) and its theoretical extension to sexual satisfaction—the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction (Lawrance & Byers, 1995). Although both sexual and marital satisfaction decline over time (e.g., McNulty et al., 2016), there is substantial between-person variability in these trajectories (Ghodse-Elahi et al., 2021; Proulx et al., 2017). Indeed, findings from latent class analyses suggest that initial satisfaction helps account for such variability—individuals who remain satisfied with their relationships were satisfied at the outset, whereas others who show the steepest decline were less satisfied at the outset (Proulx et al., 2017). The bidirectional association that emerged here perhaps helps explain why these initial differences in satisfaction widen over time. Individuals who are initially more satisfied with their marriages engage in more positive interactions, such as sex, which leads to continued marital happiness. In contrast, individuals who are less satisfied with their marriages at the outset may engage in less satisfying sex, leading to reduced satisfaction with the marriage, and even more reduced sexual satisfaction in the future. The vicious cycle continues. Given that this process appears to operate at a daily level, it is not surprising that relationships can change as quickly as they do.

Further, our moderation findings suggest that stress accelerates this process. We conducted several exploratory analyses to examine potential moderators of the bidirectional association between sexual and marital satisfaction. Daily stress emerged as the only reliable moderator after we corrected the familywise error rate of these tests. Specifically, daily stress moderated both directions of the bidirectional association between sexual and marital satisfaction, as well as the association between sex that occurred on one day and marital satisfaction the next day. Specifically, (a) global sexual satisfaction on one day predicted marital satisfaction the next day when stress the next day was higher than normal, but not when stress the next day was lower than normal; (b) marital satisfaction on one day predicted global sexual satisfaction the next day when stress the next day was higher than normal, but not when stress the next day was lower than normal; (c) and satisfaction with sex that occurred that day more strongly predicted marital satisfaction the next day when stress the next day was higher rather than lower than normal.

These findings join existing theory (Karney & Bradbury, 1995) and research (Hicks et al., 2020; McNulty et al., 2021; Neff & Karney, 2009; for review, see Neff & Karney, 2017) in suggesting that stress accentuates the extent to which various factors predict interpersonal outcomes. In one set of studies, for example, Neff & Karney (2009) demonstrated that stress accentuated the extent to which individuals’ overall evaluations of their relationships relied on their evaluations of specific domains in the relationships, assessed as the mean of their evaluations across these various domains, including the sexual one. Here, we uncovered the same tendency using only evaluations of the sexual domain (i.e., global sexual satisfaction and evaluations of specific occurrences of sex). Moreover, we also demonstrated the same tendency in reverse—individuals facing more stress used their global evaluations of the relationship when evaluating their sexual relationship. Intriguingly, stress did not accentuate the extent to which individuals used their global evaluations of the relationship when evaluating their satisfaction with specific occurrences of sex the next day, suggesting some limits to this tendency.

The fact that stress accentuates the strength of the bidirectional association helps elucidate why stress is so critical to relationship development. A recent effort by 86 relationship scientists pooling existing data from their longitudinal studies used machine learning to examine relationship development, but this effort failed to detect changes in relationship satisfaction over time as a function of actor and partner qualities, as well as relationship processes (Joel et al., 2020). A follow-up study pooling 10 longitudinal datasets with 1104 newlywed couples also failed to detect changes in satisfaction over several years using observations of behavior and self-report measures of neuroticism and attachment security (McNulty et al., 2021). Yet, this latter effort uncovered changes in satisfaction when accounting for the moderating role of both partners’ reports of stress. In fact, every variable examined in said analysis interacted with changes in stress to predict changes in marital satisfaction. Clearly, stress is crucial to relationship functioning, and these findings help explain why—stress activates psychological processes critical to marital development (McNulty et al., 2021). Even the robust bidirectional association between sexual and relationship satisfaction observed here and elsewhere (Lawrance & Byers, 1995; McNulty et al., 2016; Quinn-Nilas, 2020) was nonsignificant for individuals experiencing low stress. That is, relationships do not change in a vacuum—they change in response to stress (see Neff & Karney, 2017).

Several other interactions trended toward significance and are described in Supplemental Materials. Given their exploratory nature, however, we recommend readers interpret all three of these trending interactive effects with caution until they can be replicated by future research. Indeed, most interactive effects were not significant. It is of course possible that type II errors contributed to some of these null associations, since Bonferroni corrections have been criticized for increasing type II error rates (Perneger, 1998). Additionally, some measures of the moderators lacked adequate internal consistency, which could have contributed to the predominantly nonsignificant moderation findings. Nevertheless, our interpretation of the numerous null interaction effects is that the bidirectional association is rather robust and consistent, with an exception involving stress. Indeed, this bidirectional effect that emerged here has already been observed several times (Lawrance & Byers, 1995; McNulty et al., 2016; Quinn-Nilas, 2020). Further, most of our scales demonstrated high reliability and most interactions were nonsignificant even before correcting for the familywise error rate. That is, even a liberal interpretation of our interaction effects would suggest that the bidirectional association was rather consistent across individual differences.

Strengths and Limitations

Several strengths of the current research enhance our conclusions above. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the bidirectional association between sexual and relationship satisfaction at the daily level. Second, unlike much existing literature sampling newlywed couples (e.g., Cao et al., 2019; McNulty et al., 2016), the current investigation drew from participants of varying marriage lengths (see Quinn-Nilas, 2020). Third, the current investigation included two evaluative measures of the sexual relationship: daily global sexual satisfaction and satisfaction with sex that occurred that day. Both measures revealed similar associations to marital satisfaction, which further enhanced our confidence in the findings. Moreover, our novel measure assessing satisfaction with sex that occurred that day suggests that such effects extend to evaluations of specific occurrences of sex. Indeed, compared to global sexual satisfaction, this measure demonstrated more within-person than between-person variability. Future research may thus benefit from exploring ways in which this variable differs from daily global sexual satisfaction. Lastly, our bidirectional association remained significant when we statistically controlled for numerous potential covariates, suggesting that the current findings are robust.

The strengths notwithstanding, this study has important limitations. Because we sampled married individuals, we were unable to examine dyadic effects proposed by the actor-partner interdependence model (Cook & Kenny, 2005; Kenny, 1996). In addition, participants in our study were predominantly Caucasian heterosexual females residing in anglophone regions. For these reasons, our findings may lack generalizability to other populations. Furthermore, our measures for construal level and childhood unpredictability bore unimpressive internal consistency, which may have contributed to some of the nonsignificant moderation findings. Of note, we measured construal level with a shortened version of the Behavioral Identification Form (Slepian et al., 2015; Vallacher & Wegner, 1989). It is possible that the omission of certain items reduced the reliability of this measure (Luguri et al., 2012; Slepian et al., 2015). As for our measure of childhood unpredictability, it demonstrated substandard reliability in prior research (e.g., Simpson et al., 2012). On a related note, although prior daily-diary studies (e.g., Dobson et al., 2020; Impett et al., 2012; Little et al., 2010) and psychometric research findings (e.g., Bergkvist & Rossiter, 2007; Elo et al., 2003; Milton et al., 2011) underpin the validity of single-item measures, they may still underperform in comparison to multi-item measures. Lastly, informing participants about the aim of the broader investigation being on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on families may have highlighted stress, thereby contributing to the significant moderation with daily stress in the bidirectional association.

Conclusion

Although theoretical frameworks suggest a bidirectional association between sexual and relationship satisfaction, empirical evidence has been mixed. The current investigation sampled married individuals using a 12-day diary design to reveal a significant bidirectional association. Sexual satisfaction one day significantly predicted marital satisfaction the next day, and marital satisfaction one day significantly predicted sexual satisfaction the next day. Among numerous moderators, only daily stress robustly moderated this bidirectional association, such that it was mostly amplified under conditions of high stress, thereby joining other studies to demonstrate the ways in which stress exerts its effects on relationships (see McNulty et al., 2021; Neff & Karney, 2009).

Data Availability

Data and SPSS syntax used for analysis are available upon request.

References

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586

Allred, S. R., Crawford, L. E., Duffy, S., & Smith, J. (2016). Working memory and spatial judgments: Cognitive load increases the central tendency bias. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 23(6), 1825–1831. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-016-1039-0

Aronoff, J. E., & DeCaro, J. A. (2019). Life history theory and human behavior: Testing associations between environmental harshness, life history strategies and testosterone. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.015

Arriaga, X. B. (2013). An interdependence theory analysis of close relationships. In J. A. Simpson & L. Campbell (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of close relationships (pp. 39–65). Oxford University Press.

Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126(3), 347. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.347

Baumeister, R. F., & Bratslavsky, E. (1999). Passion, intimacy, and time: Passionate love as a function of change in intimacy. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0301_3

Belsky, J., Schlomer, G. L., & Ellis, B. J. (2012). Beyond cumulative risk: Distinguishing harshness and unpredictability as determinants of parenting and early life history strategy. Developmental Psychology, 48(3), 662–673. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024454

Bender, R., & Lange, S. (2001). Adjusting for multiple testing—When and how? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(4), 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00314-0

Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.44.2.175

Birnbaum, G. E. (2007). Attachment orientations, sexual functioning, and relationship satisfaction in a community sample of women. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407507072576

Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J.-P. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. Guilford Press.

Bolger, N., & Schilling, E. A. (1991). Personality and the problems of everyday life: The role of neuroticism in exposure and reactivity to daily stressors. Journal of Personality, 59(3), 355–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00253.x

Brumbach, B. H., Figueredo, A. J., & Ellis, B. J. (2009). Effects of harsh and unpredictable environments in adolescence on development of life history strategies: A longitudinal test of an evolutionary model. Human Nature, 20(1), 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-009-9059-3

Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15(1), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00189.x

Byers, E. S. (2005). Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 42(2), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490509552264

Cao, H., Zhou, N., Fine, M. A., Li, X., & Fang, X. (2019). Sexual satisfaction and marital satisfaction during the early years of Chinese marriage: A three-wave, cross-lagged, actor-partner interdependence model. Journal of Sex Research, 56(3), 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1463503

Cook, W. L., & Kenny, D. A. (2005). The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250444000405

del Sánchez-Fuentes Mar, M., & Santos-Iglesias, P. (2016). Sexual satisfaction in Spanish heterosexual couples: Testing the interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 42(3), 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2015.1010675

DeLamater, J. D., & Sill, M. (2005). Sexual desire in later life. Journal of Sex Research, 42(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490509552267

Diamond, L. M. (2003). What does sexual orientation orient? A biobehavioral model distinguishing romantic love and sexual desire. Psychological Review, 110(1), 173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.110.1.173

Dishion, T. J., Ha, T., & Véronneau, M.-H. (2012). An ecological analysis of the effects of deviant peer clustering on sexual promiscuity, problem behavior, and childbearing from early adolescence to adulthood: An enhancement of the life history framework. Developmental Psychology, 48(3), 703. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027304

Dobson, K., Zhu, J., Balzarini, R. N., & Campbell, L. (2020). Responses to sexual advances and satisfaction in romantic relationships: Is yes good and no bad? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(6), 801–811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619888884

Dutton, K. A., & Brown, J. D. (1997). Global self-esteem and specific self-views as determinants of people’s reactions to success and failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(1), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.139

Ellis, B. J., & Symons, D. (1990). Sex differences in sexual fantasy: An evolutionary psychological approach. Journal of Sex Research, 27(4), 527–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499009551579

Elo, A.-L., Leppänen, A., & Jahkola, A. (2003). Validity of a single-item measure of stress symptoms. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 29(6), 444–451.

Fallis, E. E., Rehman, U. S., Woody, E. Z., & Purdon, C. (2016). The longitudinal association of relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction in long-term relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(7), 822. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000205

Fisher, T. D., & McNulty, J. K. (2008). Neuroticism and marital satisfaction: The mediating role played by the sexual relationship. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.112

Fletcher, G. J. O., Simpson, J. A., Thomas, G., & Giles, L. (1999). Ideals in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.1.72

Forgas, J. P. (1994a). Sad and guilty? Affective influences on the explanation of conflict in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.1.56

Forgas, J. P. (1994b). The role of emotion in social judgments: An introductory review and an Affect Infusion Model (AIM). European Journal of Social Psychology, 24(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420240102

Ghodse-Elahi, Y., Neff, L. A., & Shrout, P. E. (2021). Modeling dyadic trajectories: Longitudinal changes in sexual satisfaction for newlywed couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(8), 3651–3662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02075-9

Golden, R. L., Furman, W., & Collibee, C. (2016). The risks and rewards of sexual debut. Developmental Psychology, 52(11), 1913. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000206

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1

Haavio-Mannila, E., & Kontula, O. (1997). Correlates of increased sexual satisfaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26(4), 399–419. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024591318836

Hicks, L. L., McNulty, J. K., Faure, R., Meltzer, A. L., Righetti, F., & Hofmann, W. (2020). Do people realize how their partners make them feel? Relationship enhancement motives and stress determine the link between implicitly assessed partner attitudes and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(2), 335. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000247

Hofmann, W., Schmeichel, B. J., & Baddeley, A. D. (2012). Executive functions and self-regulation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(3), 174–180.

Impett, E. A., Kogan, A., English, T., John, O., Oveis, C., Gordon, A. M., & Keltner, D. (2012). Suppression sours sacrifice: Emotional and relational costs of suppressing emotions in romantic relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(6), 707–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212437249

Joel, S., Eastwick, P. W., Allison, C. J., Arriaga, X. B., Baker, Z. G., Bar-Kalifa, E., Bergeron, S., Birnbaum, G. E., Brock, R. L., Brumbaugh, C. C., Carmichael, C. L., Chen, S., Clarke, J., Cobb, R. J., Coolsen, M. K., Davis, J., de Jong, D. C., Debrot, A., DeHaas, E. C., & Wolf, S. (2020). Machine learning uncovers the most robust self-report predictors of relationship quality across 43 longitudinal couples studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(32), 19061–19071. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1917036117

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1997). Neuroticism, marital interaction, and the trajectory of marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(5), 1075. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.5.1075

Kelley, H. H., & Thibaut, J. W. (1978). Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. Wiley.

Kenny, D. A. (1996). Models of non-independence in dyadic research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13(2), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407596132007

Kisler, T. S., & Christopher, F. S. (2008). Sexual exchanges and relationship satisfaction: Testing the role of sexual satisfaction as a mediator and gender as a moderator. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(4), 587–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508090874

Larson, J. H., Anderson, S. M., Holman, T. B., & Niemann, B. K. (1998). A longitudinal study of the effects of premarital communication, relationship stability, and self-esteem on sexual satisfaction in the first year of marriage. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 24(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926239808404933

Laumann, E. O., & Waite, L. J. (2008). Sexual dysfunction among older adults: Prevalence and risk factors from a nationally representative U.S. probability sample of men and women 57–85 years of age. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(10), 2300–2311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00974.x

Lawrance, K.-A., & Byers, E. S. (1995). Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 2(4), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00092.x

Little, K. C., McNulty, J. K., & Russell, V. M. (2010). Sex buffers intimates against the negative implications of attachment insecurity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(4), 484–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209352494

Luguri, J. B., Napier, J. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (2012). Reconstruing intolerance: Abstract thinking reduces conservatives’ prejudice against nonnormative groups. Psychological Science, 23(7), 756–763. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611433877

Maxwell, J. A., & McNulty, J. K. (2019). No longer in a dry spell: The developing understanding of how sex influences romantic relationships. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(1), 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721418806690

McNulty, J. K., Wenner, C. A., & Fisher, T. D. (2016). Longitudinal associations among relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and frequency of sex in early marriage. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(1), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0444-6

McNulty, J. K., Meltzer, A. L., Neff, L. A., & Karney, B. R. (2021). How both partners’ individual differences, stress, and behavior predict change in relationship satisfaction: Extending the VSA model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(27), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2101402118

Meltzer, A. L., & McNulty, J. K. (2010). Body image and marital satisfaction: Evidence for the mediating role of sexual frequency and sexual satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(2), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019063

Milton, K., Bull, F. C., & Bauman, A. (2011). Reliability and validity testing of a single-item physical activity measure. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(3), 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2009.068395

Mitchell, K. R., Mercer, C. H., Ploubidis, G. B., Jones, K. G., Datta, J., Field, N., Copas, A. J., Tanton, C., Erens, B., Sonnenberg, P., Clifton, S., Macdowall, W., Phelps, A., Johnson, A. M., & Wellings, K. (2013). Sexual function in Britain: Findings from the third national survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles (Natsal-3). The Lancet, 382(9907), 1817–1829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62366-1

Muise, A., Kim, J. J., McNulty, J. K., & Impett, E. A. (2016). The positive implications of sex for relationships. In C. Knee & H. Reis (Eds.), Advances in personal relationships: Positive approaches to optimal relationship development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Neff, L. A., & Karney, B. R. (2003). The dynamic structure of relationship perceptions: Differential importance as a strategy of relationship maintenance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(11), 1433–1446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203256376

Neff, L. A., & Karney, B. R. (2009). Stress and reactivity to daily relationship experiences: How stress hinders adaptive processes in marriage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(3), 435. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015663

Neff, L. A., & Karney, B. R. (2017). Acknowledging the elephant in the room: How stressful environmental contexts shape relationship dynamics. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 107–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.013

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(4), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.35.4.250

Peck, S. R., Shaffer, D. R., & Williamson, G. M. (2004). Sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction in dating couples: The contributions of relationship communality and favorability of sexual exchanges. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 16(4), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v16n04_02

Pedersen, W., & Blekesaune, M. (2003). Sexual satisfaction in young adulthood: Cohabitation, committed dating or unattached life? Acta Sociologica, 46(3), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/00016993030463001

Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S., & Acquisti, A. (2017). Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.01.006

Peplau, L. A. (2003). Human sexuality: How do men and women differ? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(2), 37–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01221

Perneger, T. V. (1998). What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. British Medical Journal, 316(7139), 1230–1240. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1236

Proulx, C. M., Ermer, A. E., & Kanter, J. B. (2017). Group-based trajectory modeling of marital quality: A critical review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(3), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12201

Quinn-Nilas, C. (2020). Relationship and sexual satisfaction: A developmental perspective on bidirectionality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(2), 624–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519876018

Raposo, S., & Muise, A. (2021). Perceived partner sexual responsiveness buffers anxiously attached individuals’ relationship and sexual quality in daily life. Journal of Family Psychology, 35(4), 500–509. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000823

Roch, S. G., Lane, J. A. S., Samuelson, C. D., Allison, S. T., & Dent, J. L. (2000). Cognitive load and the equality heuristic: A two-stage model of resource overconsumption in small groups. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 83(2), 185–212. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2000.2915

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton University Press.

Rubin, H., & Campbell, L. (2012). Day-to-day changes in intimacy predict heightened relationship passion, sexual occurrence, and sexual satisfaction: A dyadic diary analysis. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 3(2), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611416520

Russell, V. M., & McNulty, J. K. (2011). Frequent sex protects intimates from the negative implications of their neuroticism. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(2), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550610387162

Schachner, D. A., & Shaver, P. R. (2004). Attachment dimensions and sexual motives. Personal Relationships, 11(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00077.x

Schaffhuser, K., Wagner, J., Lüdtke, O., & Allemand, M. (2014). Dyadic longitudinal interplay between personality and relationship satisfaction: A focus on neuroticism and self-esteem. Journal of Research in Personality, 53, 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.08.007

Schneider, D., Lam, R., Bayliss, A. P., & Dux, P. E. (2012). Cognitive load disrupts implicit theory-of-mind processing. Psychological Science, 23(8), 842–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612439070

Schoofs, D., Preuß, D., & Wolf, O. T. (2008). Psychosocial stress induces working memory impairments in an n-back paradigm. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33(5), 643–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.02.004

Schumm, W. R., Nichols, C. W., Schectman, K. L., & Grigsby, C. C. (1983). Characteristics of responses to the Kansas marital satisfaction scale by a sample of 84 married mothers. Psychological Reports, 53(2), 567–572. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1983.53.2.567

Segal, N. L., & Stohs, J. H. (2009). Age at first intercourse in twins reared apart: Genetic influence and life history events. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(2), 127–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.02.010

Simpson, J. A., Rholes, W. S., & Phillips, D. (1996). Conflict in close relationships: An attachment perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(5), 899–914. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.5.899

Simpson, J. A., Griskevicius, V., Kuo, S.I.-C., Sung, S., & Collins, W. A. (2012). Evolution, stress, and sensitive periods: The influence of unpredictability in early versus late childhood on sex and risky behavior. Developmental Psychology, 48(3), 674–686. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027293

Slepian, M. L., Masicampo, E. J., & Ambady, N. (2015). Cognition from on high and down low: Verticality and construal level. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038265

Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (2011). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Sprecher, S. (2002). Sexual satisfaction in premarital relationships: Associations with satisfaction, love, commitment, and stability. Journal of Sex Research, 39(3), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490209552141

Szepsenwol, O., Simpson, J. A., Griskevicius, V., & Raby, K. L. (2015). The effect of unpredictable early childhood environments on parenting in adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 1045. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000032

Szepsenwol, O., Griskevicius, V., Simpson, J. A., Young, E. S., Fleck, C., & Jones, R. E. (2017). The effect of predictable early childhood environments on sociosexuality in early adulthood. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 11(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000082

Thibaut, J. W., & Kelley, H. H. (1959). The social psychology of groups. John Wiley.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018963

Vallacher, R. R., & Wegner, D. M. (1989). Levels of personal agency: Individual variation in action identification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(4), 660–671. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.4.660

Vigil, J. M. (2005). A life history assessment of early childhood sexual abuse in women. Developmental Psychology, 41(3), 553. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.3.553

Vowels, L. M., & Mark, K. P. (2020). Relationship and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal actor–partner interdependence model approach. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 35(1), 46–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2018.1441991

Weidmann, R., Ledermann, T., & Grob, A. (2017). Big Five traits and relationship satisfaction: The mediating role of self-esteem. Journal of Research in Personality, 69, 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.06.001

Weiss, R. L. (1980). Strategic behavioral marital therapy: Toward a model for assessment and intervention. In J. P. Vincent (Ed.), Advances in family intervention assessment and theory (pp. 229–271). JAI Press.

Williamson, H. C., Bornstein, J. X., Cantu, V., Ciftci, O., Farnish, K. A., & Schouweiler, M. T. (2022). How diverse are the samples used to study intimate relationships? A systematic review. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(4), 1087–1109. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211053849

Woo, J. S. T., & Brotto, L. A. (2008). Age of first sexual intercourse and acculturation: Effects on adult sexual responding. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(3), 571–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00740.x

Wright, S. P. (1992). Adjusted p-values for simultaneous inference. Biometrics, 48(4), 1005–1013. https://doi.org/10.2307/2532694

Yeh, H.-C., Lorenz, F. O., Wickrama, K. A. S., Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H., Jr. (2006). Relationships among sexual satisfaction, marital quality, and marital instability at midlife. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(2), 339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.339

Funding

For this research was provided by the Office of Research at Florida State University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Florida State University (study number: STUDY00001387).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, C., McNulty, J.K., Turner, J.A. et al. Evidence of a Bidirectional Association Between Daily Sexual and Relationship Satisfaction That Is Moderated by Daily Stress. Arch Sex Behav 51, 3791–3806 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02399-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02399-0