Abstract

People with HIV (PWH) are at risk for adverse mental health outcomes, which could be elevated during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study describes reasons for changes in mental health among PWH during the pandemic. Data come from closed- and open-ended questions about mental health changes from a follow-up to a cohort study on PWH in Florida during part of the COVID-19 pandemic (May 2020–March 2021). Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis. Among the total sample of 227 PWH (mean age 50.0, 49.7% men, 69.2% Black/African American, 14.1% Hispanic/Latino), 30.4% reported worsened mental health, 8.4% reported improved mental health, and 61.2% reported no change. The primary reasons for worsened mental health were concerns about COVID-19, social isolation, and anxiety/stress; reasons for improved mental health included increased focus on individual wellness. Nearly one-third of the sample experienced worsened mental health. These results provide support for increased mental health assessments in HIV treatment settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the first cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus, were identified in December 2019, life has not been the same for many as social distancing guidelines and mandatory mask orders have been implemented, daily lives have been disrupted, and behaviors and overall health have changed worldwide. Mental health in particular has been significantly impacted by COVID-19 [1]. Studies in Europe have found that quality of life and symptoms of depression and anxiety have worsened among the general population since the start of the pandemic, while the prevalence of mental health problems has increased [2,3,4]. In the United States, 42% of Americans reported symptoms of depression or anxiety in December 2020 compared with 11% the previous year [5]. There is also evidence that changes in mental health due to COVID-19 may differ by racial/ethnic groups and by gender [6, 7].

People with HIV (PWH) report a higher prevalence of mental health conditions than the general population, and mental health conditions can increase not only the risk for acquiring HIV but also the risk for negative health outcomes at each step along the cascade of HIV care; this includes measures such as being on antiretroviral therapy (ART) and being virally suppressed [8,9,10,11,12]. It is possible that, as in the general population, the COVID-19 pandemic could have severely impacted the mental health of this already susceptible population. PWH might experience negative health outcomes associated with a COVID-19 diagnosis and from pandemic safety measures such as social distancing measures and closed provider offices that may interrupt healthcare access [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Previous studies have found marked changes in mental health [20, 21] and increases in substance use [22] among PWH during the pandemic. Negative economic consequences of the pandemic have also caused stress and worsened mental health outcomes for some PWH [19, 20, 23]. Additionally, factors that can influence the health and wellness of PWH in normal conditions such as self-efficacy [24], perceived stress [25,26,27], resilience [28, 29], and social support [30, 31] could have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and indirectly led to changed mental health outcomes [32]. Understanding the impact of individual attributes on mental health in the pandemic could inform interventions aimed at strengthening positive attributes.

Prior studies of COVID-19 have examined changes in mental health and reasons behind the changes; however, they have primarily been surveys without great opportunity for qualitative data collection. For example, an anonymous online survey of PWH in Buenos Aires, Argentina found that the COVID-19 pandemic caused economic disruption, loneliness, reduced ART adherence, and disrupted mental health and substance use treatment for many [23]. Another web-based survey in Turkey found that anxiety and stress increased among PWH during the pandemic, and this was associated with having a preexisting psychiatric disorder, worrying about COVID-19 in the environment, uncertainty about the correct preventive procedures, and having a household member with a chronic disease [21]. Despite existing information about changes in mental health experienced during the pandemic, there are gaps in our knowledge about the exact experiences PWH are having that might influence their mental health and how they do so. Qualitative data from open-ended questions could fill these gaps. Answers from open-ended questions in addition to quantitative survey questions have more detail and nuance than survey responses alone [33]. Open-ended questions can offer opportunities for new, unexpected insights from PWH through providing additional information on reasons for changes in mental and physical health and experiences with barriers to health and well-being. Moreover, to our knowledge there are few studies looking at PWH’s responses to the COVID-19 pandemic qualitatively through open-ended survey responses combined with quantitative survey questions.

Assessing and understanding the aspects of the pandemic that were most responsible for changes in mental health among PWH, and realizing why some PWH are resilient in a crisis and why others struggle, could provide important insights into how to address the current and future health needs of PWH. The objectives of this study are to (1) describe self-reported changes in the mental health of a sample of PWH in Florida due to the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) identify demographic and behavioral variables associated with these changes, and (3) understand the reasons behind these changes through an analysis of open-ended questions. These findings can assist public health programs, clinics, or programs such as Ryan White in offering better support for specific issues that are affecting mental health for their patients with HIV. These findings might also allow researchers and providers to learn from those PWH who do well in public health crises to inform new and existing interventions.

Methods

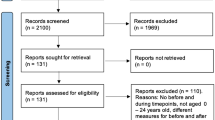

Study and Study Participants

This study analyzed data from the Marijuana Associated Planning and Long-Term Effects (MAPLE) study, a prospective cohort study with a focus on determining the long-term health effects of marijuana on PWH. As of July 2021, there were 300 PWH enrolled in the cohort. Since October 2018, participants have been recruited through clinics at county Departments of Health, infectious disease clinics, community healthcare centers, and flyers placed in three recruitment settings in Florida. Participants who do and who do not use marijuana are eligible for the study, with planned enrollment targeting three participants who use marijuana for every one participant who does not. At the baseline, each participant completed a survey, a blood test, and a urine test to establish marijuana use status. All participants also received a brief telephone-based follow-up survey every 3 months and an in-person follow-up visit every 12 months. During a peak period of the COVID-19 pandemic, between May 2020 and March 2021, the research team added several additional questions to the existing 3-month telephone-based follow-up that aimed to evaluate changes in mental health. This paper presents the analysis of a sub-cohort of 227 PWH, from the larger cohort of 300 PWH (response rate: 75.7%), who responded to the 3-month follow-up brief telephone survey with questions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The foci of this analysis are the changes in mental health and the reasons for the changes experienced by this sub-cohort.

Measures

At baseline, collected between 2018 and 2020, all participants completed a survey that assessed their age, sex, race, ethnicity, income, education (scored on a three-tier scale of less than high school, high school or equivalent, and more than high school), and health behaviors such as ART medication usage and adherence, current marijuana use (confirmed with a positive urine test of Tetrahydrocannabinol), and self-reported past-year alcohol use. Baseline depression was measured using the PHQ-8 [34]. In the 3-month follow-up call, age was collected again. The researchers explained that questions in the follow-up pertained to the “coronavirus situation,” the COVID-19 pandemic which was defined as beginning in Florida on March 1, 2020. Self-reported changes in mental health were assessed using the following question: “When considering your mental health, how would you say your mental health has changed since before the coronavirus situation until today?” The answer options were on a Likert scale from “1-much better” to “5-much worse”, with a higher score indicating a worsened degree of mental health. If participants indicated a positive or negative change in mental health, they were asked a follow-up, open-ended question, “What would you say is the main reason for that change?” Participants could give as many reasons as they felt appropriate and as many details as they wished in their response or skip the question entirely, although no participants who indicated a change in mental health skipped the open-ended follow-up question. Only two participants (0.9%) had a positive COVID-19 test and thus COVID-19 diagnosis was not analyzed further in the results.

Analysis

A descriptive analysis of participants’ sociodemographic characteristics and behaviors was done in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). Descriptive statistics were calculated to evaluate the frequency of reported changes in mental health and significant differences by key sociodemographic variables were determined using chi-sq/Fisher’s exact or ANOVA depending on the variable and sample size. Additional logistic regression analyses, controlling for variables significantly associated with changes in mental health, were conducted. Two logistic regression models were made to investigate the predictive effects of the significant variables on either a worsening of or an improvement in mental health compared with no change.

Thematic analysis adapted for our data was used for the open-ended questions [35, 36]. Qualitative data from the open-ended question about reasons for changes in mental health were compiled in Microsoft Excel and manually coded by two independent coders using a codebook created by the primary author. Additional codes were generated by the coders as new themes emerged from the participant responses. The coding was done by two independent coders who discussed the codebook before coding began, met after completing the coding to compare results, and reviewed any disagreements before coming to a shared conclusion. Codes were categorized under broader themes to understand reasons for changes in mental health, with separate sets of codes created for people who indicated an improvement in their mental health and those who indicated a worsening of their mental health.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 presents the study participants’ characteristics. The current average age of the participants was 50.0 years (SD = 11.1). Sixty-one percent of the participants were 50 years or older and 50.2% of the participants were female. Most of the participants were Black/African American (69.1%), followed by White (22.4%), and other race (8.4%). Of the total participants, 14.1% were Hispanic. Over one-quarter (29.1%) had less than a high school education and 70.0% made less than $20,000 per annum. Most of the participants (94.3%) were currently taking ART medication. At baseline, nearly one-third of the sample had mild depression while 27.8% had moderate or severe depression. Additionally, 80.2% of the sample currently used marijuana and 76.2% had past-year alcohol use.

Sixty-nine participants (30.4%) indicated their mental health worsened due to the pandemic compared with 19 (8.4%) who indicated improvement and 139 (61.2%) who reported no change. Beyond baseline depression measured by PHQ-8 score (p = 0.004) and education level (p = 0.020), there were no statistically significant differences in changes in mental health by baseline characteristics. Over half of those with moderate depression experienced worsened mental health compared with 42.9% of those with severe depression, 28.8% of those with mild depression, and 16.5% of those with minimal or no depression. Nearly 40% of those with greater than a high school education experienced worsened mental health compared with only 27.3% of those with a high school education and 22.7% of those with less than a high school education.

Levels of education and depression had a significant predictive relationship in the logistic regression models. Having more than a high school education was associated with increased odds of reporting worsened mental health (odds ratio: 3.47, 95% confidence interval 1.52–7.90, χ2: 8.77, p = 0.003), rather than no change in mental health; having less than a high school education was not significantly associated with worsened mental health. Similarly, having mild (OR: 2.29, 95% CI 1.02–5.17, χ2: 3.98, p = 0.046), moderate (OR: 8.00, 95% CI 3.00–21.31, χ2: 17.30, p < 0.001), or severe depression (OR: 4.15, 95% CI 1.51–11.38, χ2: 7.65, p = 0.006) compared with having no or minimal depression was also associated with increased odds of reporting worsened mental health. Participants with more than a high school education had increased odds of reporting improved mental health, rather than no change in mental health, compared with those who had less than a high school education (OR: 5.72, 95% CI 1.34–24.44, χ2: 5.55, p = 0.019), as did those with moderate depression (OR: 4.88, 95% CI 1.07–22.24, χ2: 4.20, p = 0.040) compared to those with no or minimal depression. These results can be seen in the Supplementary materials (Supplementary Tables I and II).

Reasons for Changes in Mental Health

Worsened Mental Health

Table 2 describes the codes and the frequency of reasons for worsened health among the study participants. Sixty-nine participants (30.4%) indicated that their mental health worsened; however, the reasons as to why mental health worsened varied. Over one-quarter of participants indicated that their mental health worsened because of worrying about their risk or a loved one’s risk of contracting COVID-19. Some participants had public-facing jobs that required them to interact with the public, creating more opportunities for COVID-19 exposure which caused constant worry leading to worsened mental health. Other participants expressed concerns about whether COVID-19 was real or if it was a conspiracy theory.

-

“Since I had to go back to work [at a coffee shop], I started to see a lot of people, and deal with a lot of people, especially homeless people who are becoming more concentrated in the location where I work after the coronavirus, and I have to deal with vandalism and customer services. This all has made me very stressed.” (51-year-old White woman)

-

“I am more paranoid mostly about getting COVID or if it is even real.” (36-year-old Black and Hispanic woman)

Additionally, 13.0% of participants felt that their risk of COVID-19 exposure was beyond their control. Some cited a lack of trust in their community members to follow COVID-19 guidelines, such as social distancing and wearing masks. Some participants also believed the COVID-19 guidelines would not protect them from COVID-19, instilling a sense of hopelessness that worsened their mental health.

-

“It feels like the community is not taking COVID seriously like with wearing masks.” (25-year-old White and Hispanic man)

-

“I am irritated more now especially with the back and forth on masks, we have to wear them and then don’t have to wear them. I believe masks will not help. They aren’t effective and it’s like putting pants on to cover up a fart. They won’t prevent the virus from coming in.” (55-year-old multiracial man)

Worries about contracting COVID were often cited alongside PWH’s beliefs that they were at higher risk for COVID-19. Some were unsure whether their HIV status would put them at greater risk for contracting COVID-19 or developing complications. About 6% of participants expressed trouble with their medical care or access, or limited knowledge about accessing care with the COVID-19 restrictions, that worsened their mental health.

-

“I am concerned because I am immunocompromised, so I am worried about being around others and going out.” (46-year-old Black woman)

-

“I do not know how to go about going to the doctor’s office.” (56-year-old Black woman)

Adding to these concerns, many PWH were unable to adhere to their medication or receive their regular care. Others had another comorbid condition they were unable to receive regular or proper care for that put them at enhanced risk for negative COVID outcomes. One participant also stated that while telehealth and phone appointments were available for them to receive their usual care, those appointment methods were not ideal for them due to the anxiety they caused.

-

“Instead of being seen in person, an ARNP changed my medication and was not as thorough as my usual provider, causing the removal of my medication.” (51-year-old multiracial female)

-

“My psychiatrist wants to talk over the phone which gives me panic attacks.” (25-year-old White Hispanic man)

Seven participants had preexisting mental health conditions that were exacerbated by pandemic conditions.

-

“I am bipolar and experiencing a lot of anxiety and a lot more downs.” (52-year-old Black woman)

-

“I generally suffer from depression, I have been isolating myself even before the coronavirus problem started. Lately, there has been a lot of negativity surrounding me, and people are becoming unraveled, the problem of the pandemic, politics, and a lot of crazy stuff going on, people are weird. I even left Facebook.” (51-year-old White woman)

Many expressed concerns about the wellbeing of family and friends, since they could not meet or check in with them regularly. Others lost their loved ones and were feeling sad from their loss.

-

“I am worried, I haven’t been able to see my sister.” (71-year-old White man)

-

“I am taking it one day at a time. My mother passed away last week.” (52-year-old Black woman)

Five participants experienced worsened mental health due to being unable to make their ends meet financially. This may have been because of unexpected medical or other expenses that they were experiencing during the pandemic. Additionally, five people indicated that a change in their career status, such as suddenly losing their job or being furloughed, worsened their mental health.

-

“I am not able to make ends meet with no work.” (33-year-old Black woman)

-

“I am not working and staying at home. It is mainly because of the loneliness, and money issues. It has affected me emotionally, I feel stressed, and it just goes along with my depression.” (25-year-old White man)

Staying in was another prominent factor that reportedly worsened mental health for the participants. Being isolated at home with “cabin fever” and in general having to stay away from others contributed to worse mental health for eight participants. Not being able to do usual activities that brought the participants joy or helped them maintain their mental and physical health, such as going to the gym, religious gatherings, or meeting with friends in person also worsened mental health for five participants.

-

“I go in a room and stay by myself because of worries of bringing COVID back to my family.” (63-year-old Black man)

-

“I usually go to the gym quite frequently and have not been able to and can feel it affected my mind.” (57-year-old White man)

One participant reported that having their kids at home and out of school, along with the increased responsibilities of remote learning, led to increased feelings of stress.

-

“I have 5 kids and they are not having social interactions with peers; they are not able to do the activities they used to do. Some of them are reverting, and I have a kid who is on the autistic spectrum. This change in my kids’ schedules is causing me a lot of stress because I need to be in charge of their education, and I am trying to find some activities for them to do safely. It is tough to be responsible for teaching, especially for my kid who is on the autistic spectrum, and I myself had difficulties in learning while growing up, so it is harder for me to teach my children. Because I am worried about a wave of people testing positive … when schools open, I decided to keep my kids at home for the first 9 weeks of school. It is a very stressful situation.” (32-year-old White woman)

Improved Mental Health

Table 3 describes the frequency of reasons for improved health among the study participants. Nineteen participants (8.4%) indicated that their mental health improved during the pandemic. Many said that this was because of the stay-at-home orders that required them to stay home, which gave them an opportunity to do activities that brought them joy or engage in other coping mechanisms.

-

“For a while, I wasn’t working because of COVID, so I had more time for myself. I took a little break. I had more time to sleep more, relax, and I started journaling because I have more time.” (24-year-old Black woman)

-

“I am doing more artwork, and staying in.” (60-year-old White man)

Many indicated that the pandemic made them more mindful. Several participants also indicated that they felt comfortable with their knowledge about COVID-19 health and safety measures and their ability to follow them, which made them feel safer and more in control of their living situation during the pandemic.

-

“I am more aware of my body daily, what I do to it, and what I put in.” (25-year-old Black man)

-

“Everyone is talking to us and giving us information about different ways to protect our health. I feel like I am ready and have the knowledge needed. COVID information is making things less stressful.” (52-year-old Black man)

Some participants reported that renewed faith and religiosity helped not only with coping but also with improving their outlook on life and overall mental health.

-

“This [the pandemic] has given me a lot more spiritual strength and belief.” (59-year-old Black man)

Additionally, others indicated that, while they may have had worse mental health at the start of the pandemic, they have adapted to the situation and now feel their mental health is better than it was at the beginning of or even before the pandemic. A few participants also indicated that their resilience or a “new perspective” led to improved mental health overall.

-

“I am more relaxed and at peace with the COVID-19 situation.” (54-year-old White and Hispanic man)

-

“I am adapting to new perspectives due to coronavirus.” (27-year-old multiracial Hispanic man)

Several participants also experienced significant social support or various positive experiences such as finding a new partner or celebrating important anniversaries and birthdays, which brought them joy.

-

“I have better support. I found a new partner.” (37-year-old Black woman)

-

“I celebrated my 20th anniversary with my husband.” (43-year-old White woman)

Discussion

This study aimed to understand the changes in mental health experienced by a cohort of PWH in Florida due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the reasons behind those changes. The information from this study adds to previous research with this sample that quantitatively examined changes in mental health and its associated factors [37] by providing much-needed context to the reported changes in mental health. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using open-ended questions and combined quantitative and qualitative methods to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted mental health in PWH. Our findings on the underlying reasons for mental health changes in PWH can potentially inform interventions that aim to improve mental health among this population.

This study found that, while over 30% of the sample experienced worsened mental health, there was no significant difference in the frequency of changes in mental health by age, race, ethnicity, gender, income, or alcohol or marijuana use status, factors that had great potential to be associated with changes in mental health. The only significant differences, controlled for in additional logistic regression analyses, were that people with greater than a high school education and those who had moderate depression were more likely to experience improved mental health while those with greater than a high school education and those with any level of depression (mild, moderate, or severe) were more likely to experienced worsened mental health. It is interesting that those with greater than a high school education and those with moderate depression were more likely to experience any change in mental health, worsened or improved. Perhaps these populations are more likely to be aware of their mental health status and report a change, or experienced stressful situations differentially.

The results of this study support previous findings in the literature, using a variety of methods, about reasons why PWH have experienced changes in mental health. For example, participants reported worrying about COVID-19 [23, 38, 39], not trusting information about COVID-19 or following preventive protocols [40, 41], reduced access to healthcare [19, 42], worsening of psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression [1, 38, 42, 43], isolation and a lack of social support [39, 44,45,46], not being able to do regular and meaningful activities [47, 48], worrying about themselves or loved ones [21, 49], and financial difficulties [19, 50] as reasons why they experienced worsened mental health, all of which have been tied in the literature to the COVID-19 pandemic among both the general population and PWH. Of note, while some issues noted in the literature and by the PWH in this study might have unique causes or consequences for PWH such as reduced viral suppression, the concerns cited most often by PWH in this study apply to the general population as well. This shows that while PWH do have unique health concerns, the experiences they had during the pandemic and corresponding changes in mental health were largely like anyone else’s. This shows potential for being targeted for interventions not only at HIV care centers but at primary care and general community or online locations as well.

A strength of this study is that the open-ended questions allowed for more particular reasons for changes in mental health to be stated by the participants. For example, participants in this study reported that being isolated from specific locations such as the gym or church worsened their mental health, rather than just discussing general disruptions to their routine. These also give more concrete targets for future interventions; perhaps increasing access to online church services or workout classes, or social-distancing safe meetups with community members from those locations, could help PWH in similarly isolating and disruptive public health crises.

Findings from this study also highlight the factors that contribute to improved mental health among PWH during the pandemic. The most frequently mentioned factors that brought happiness and calmness among the participants were having adequate social support, occurrence of a positive life event, using the pandemic as an opportunity to focus on their health and wellbeing, pursuing activities they enjoy or have wanted to be involved in, turning to their faith, and becoming overall more resilient. This supports evidence in the literature that found that higher resilience reduced the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health among PWH [23].

A common theme that arose in the analysis was the differentiation between things that participants could control and things they could not control. Many of the items that people said worsened their mental health were beyond their individual control, while those who stated improved mental health often cited increasing their resilience, engaging in mindfulness practices and activities that brought them joy, or focusing on positive events in their lives. This may have contributed to an increased sense of control in their lives, even though those participants likely dealt with similarly stressful items as those with worsened mental health. Further research with those who improved or simply maintained their mental health during the pandemic could provide insight into effective strategies for individuals to stay well in stressful situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

These findings highlight the importance of a clear understanding regarding the factors that improve resilience and improve mental health among PWH during public health emergencies and future pandemics. It might be advised that for future public health emergencies, services that improve mindfulness and resilience should be more accessible to PWH, and perhaps be connected to them through services they already use such as their primary care or HIV provider. It might also be recommended that PWH stay involved in activities they enjoy and/or they recognize as being critical to maintaining their mental health, whether that be exercise, art, faith-related activities, or staying connected with their friends through whatever medium possible, even if they are not able to maintain it to the extent they are used to or must complete it from their home. For example, programs that aim to safely connect PWH to others in their social network, perhaps via technology, to prevent loneliness and isolation could be impactful for this population, as could interventions such as online workout or hobby groups that allow people to do activities they enjoy and relieve stress. Mindfulness interventions that aim to improve people’s attention and awareness to their present experience have been shown to reduce incidence of depression and other psychological symptoms and improve the quality of life among PWH [51], and this could be an impactful intervention to improve mental health among PWH during public health emergencies. Involving PWH’s regular providers, who likely have the best understanding of their patients’ individual needs could help in this effort. Telemedicine has become a valuable tool in the pandemic for treating PWH by greatly enhancing healthcare access [52,53,54]. In general, telemedicine has had high clinician support throughout the pandemic [55], providing more potential feasibility and sustainability for regular use during and after the pandemic. However, as one participant in this study noted, telemedicine might not be a viable option for those who have anxiety about communicating on the phone or via videocall. Keeping people engaged in their healthcare by the method most preferable and accessible to them can improve both physical and mental health outcomes, as it can help people stay in their routines and have regular contact with others.

Limitations

While a strength of the study was the wide coverage from participants around Florida, many participants were recruited for the study at clinics and other healthcare locations. This, as well as the fact that these participants have agreed to partake in a long-term cohort study, means that this sample could be more attuned to their healthcare and health needs and have improved health outcomes compared with the general PWH population or PWH who are not in regular care. To improve this limitation in future research using this cohort, the research team is making concerted efforts to recruit participants who are underrepresented and who might not have regular access to care.

Additionally, while our response rate of 75.7% was high, there could be a representativeness issue if those who did not respond were experiencing disproportionately worsened, improved, or maintained mental health. We would not know the experiences of these participants without their responses, and in the regularly scheduled upcoming follow-up sessions the research team will aim to successfully recruit these participants.

Depression was measured by an objective baseline item and changes in mental health were measured as a subjective single item, and not as a formal objective change in scores over time. Later, during the next cycle of follow-ups, we will have data that will allow us to compare the scores on depression before and after the pandemic and further investigate changes in mental health, but at this point, only baseline information and 3-month follow-up information exist.

The questions used in this study were written in May 2020, before the COVID-19 vaccine was available to the general public. Due to this, the survey questions do not ask about vaccines and issues surrounding vaccine uptake and hesitancy. Future studies with this population could examine this serious topic, as vaccine hesitancy remains a primary barrier to ending the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, this was not a formal qualitative interview, but a single open-ended question following a Likert-scale type question on subjective changes in mental health. Therefore, we lack comprehensive understanding of the spectrum of reasons that people might have had worsened mental health and only know the primary reasons that the person first thought of during the interviews. With a full interview, we might have gotten richer details on the participants’ experiences, setbacks, and triumphs. Future research involving more in-depth qualitative interviews could provide more information to fill the gaps in our knowledge.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a substantial yet varied impact on the mental health of PWH for a range of reasons. Over 30% of a sample of PWH in Florida said that their mental health worsened during the pandemic, while a small but not negligible percentage (8.4%) said their mental health improved. Understanding the reasons behind both worsened and improved mental health in this population can provide specific targets for potential interventions to maintain or even improve mental health among PWH in public health emergencies.

Data Availability of Data and Material (Data Transparency)

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;52:102066.

Pieh C, Budimir S, Probst T. The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Austria. J Psychosom Res. 2020;136:110186.

Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883–92.

Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, Colasanti M, Ferracuti S, Napoli C, et al. A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress among Italian People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020 May [cited 2021 Mar 3];17(9). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7246819/

CDC, National Center for Health Statistics, US Census Bureau. Mental Health - Household Pulse Survey - COVID-19 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Mar 3]. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm

McKnight-Eily LR. Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of stress and worry, mental health conditions, and increased substance use among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, April and May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Jul 21];70. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7005a3.htm

Thibaut F, van Wijngaarden-Cremers PJM. Women’s mental health in the time of Covid-19 pandemic. Front Glob Womens Health [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 21];0. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2020.588372/full

Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Nguyen N, Robbins RN, Pala AN, Mellins CA. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. AIDS. 2019;33(9):1411–20.

Blank MB, Himelhoch SS, Balaji AB, Metzger DS, Dixon LB, Rose CE, et al. A multisite study of the prevalence of HIV with rapid testing in mental health settings. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):2377–84.

O’Cleirigh C, Magidson JF, Skeer MR, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Prevalence of psychiatric and substance abuse symptomatology among HIV-infected gay and bisexual men in HIV primary care. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(5):470–8.

Do AN, Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, Beer L, Strine TW, Schulden JD, et al. Excess burden of depression among HIV-infected persons receiving medical care in the United States: data from the medical monitoring project and the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e92842.

Cook JA, Burke-Miller JK, Steigman PJ, Schwartz RM, Hessol NA, Milam J, et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of psychiatric and substance use disorders and associations with HIV risk behaviors in a multisite cohort of women living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(10):3141–54.

Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, Fergus TA, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. COVID stress syndrome: concept, structure, and correlates. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(8):706–14.

Lesko CR, Bengtson AM. HIV and COVID-19: intersecting epidemics with many unknowns. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190(1):10–6.

Jiang H, Zhou Y, Tang W. Maintaining HIV care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(5):e308–9.

Brown LB, Spinelli MA, Gandhi M. The interplay between HIV and COVID-19: summary of the data and responses to date. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2021;16(1):63–73.

Gervasoni C, Meraviglia P, Riva A, Giacomelli A, Oreni L, Minisci D, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with human immunodeficiency virus with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(16):2276–8.

del Amo J, Polo R, Moreno S, Díaz A, Martínez E, Arribas JR, et al. Incidence and severity of COVID-19 in HIV-positive persons receiving antiretroviral therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(7):536–41.

Santos G-M, Ackerman B, Rao A, Wallach S, Ayala G, Lamontage E, et al. Economic, mental health, HIV prevention and HIV treatment impacts of COVID-19 and the COVID-19 response on a global sample of cisgender gay men and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(2):311–21.

Algarin AB, Varas-Rodríguez E, Valdivia C, Fennie KP, Larkey L, Hu N, et al. Symptoms, stress, and HIV-related care among older people living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic, Miami Florida. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(8):2236–8.

Kuman Tunçel Ö, Pullukçu H, Erdem HA, Kurtaran B, Taşbakan SE, Taşbakan M. COVID-19-related anxiety in people living with HIV: an online cross-sectional study. Turk J Med Sci. 2020;50(8):1792–800.

Hochstatter KR, Akhtar WZ, Dietz S, Pe-Romashko K, Gustafson DH, Shah DV, et al. Potential influences of the COVID-19 pandemic on drug use and HIV care among people living with HIV and substance use disorders: experience from a pilot mHealth intervention. AIDS Behav. 2020;23:1–6.

Ballivian J, Alcaide ML, Cecchini D, Jones DL, Abbamonte JM, Cassetti I. Impact of COVID-19-related stress and lockdown on mental health among people living with HIV in Argentina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(4):475–82.

Rodkjaer L, Chesney MA, Lomborg K, Ostergaard L, Laursen T, Sodemann M. HIV-infected individuals with high coping self-efficacy are less likely to report depressive symptoms: a cross-sectional study from Denmark. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;1(22):67–72.

Huang Y, Luo D, Chen X, Zhang D, Huang Z, Xiao S. HIV-related stress experienced by newly diagnosed people living with HIV in China: a 1-year longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Apr 25]; 17(8). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7216022/

Su X, Lau JTF, Mak WWS, Chen L, Choi KC, Song J, et al. Perceived discrimination, social support, and perceived stress among people living with HIV/AIDS in China. AIDS Care. 2013;25(2):239–48.

Hand GA, Phillips KD, Dudgeon WD. Perceived stress in HIV-infected individuals: physiological and psychological correlates. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8):1011–7.

Fang X, Vincent W, Calabrese SK, Heckman TG, Sikkema KJ, Humphries DL, et al. Resilience, stress, and life quality in older adults living with HIV/AIDS. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(11):1015–21.

McGowan JA, Brown J, Lampe FC, Lipman M, Smith C, Rodger A. Resilience and physical and mental well-being in adults with and without HIV. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(5):1688–98.

Li J, Mo PKH, Wu AMS, Lau JTF. Roles of self-stigma, social support, and positive and negative affects as determinants of depressive symptoms among HIV infected men who have sex with men in China. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):261–73.

Matsumoto S, Yamaoka K, Takahashi K, Tanuma J, Mizushima D, Do CD, et al. Social support as a key protective factor against depression in HIV-infected patients: report from large HIV clinics in Hanoi, Vietnam. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):15489.

Kohls E, Baldofski S, Moeller R, Klemm S-L, Rummel-Kluge C. Mental health, social and emotional well-being, and perceived burdens of university students during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Germany. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Apr 25];12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.643957/full#B20

Albudaiwi D. Survey: open-ended questions. In: The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods [Internet]. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2017 [cited 2021 Oct 21]. p. 1716–7. https://sk.sagepub.com/reference/the-sage-encyclopedia-of-communication-research-methods/i14345.xml

Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1):163–73.

Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2011.

Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2012. p. 57–71. (APA handbooks in psychology®).

Wang Y, Ibañez GE, Vaddiparti K, Stetten NE, Sajdeya R, Porges EC, et al. Change in marijuana use and its associated factors among persons living with HIV (PLWH) during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a prospective cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;225:108770.

Holingue C, Badillo-Goicoechea E, Riehm KE, Veldhuis CB, Thrul J, Johnson RM, et al. Mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic among US adults without a pre-existing mental health condition: findings from American trend panel survey. Prevent Med. 2020;139:106231.

van Tilburg TG, Steinmetz S, Stolte E, van der Roest H, de Vries DH. Loneliness and Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study Among Dutch Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B [Internet]. [cited 2021 Apr 26];(gbaa111). Available from: 2020 Aug 5. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa111.

Pan Y, Xin M, Zhang C, Dong W, Fang Y, Wu W, et al. Associations of mental health and personal preventive measure compliance with exposure to COVID-19 information during work resumption following the COVID-19 outbreak in China: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Int Res. 2020;22(10):e22596.

Lu L, Liu J, Yuan YC, Burns KS, Lu E, Li D. Source trust and COVID-19 information sharing: the mediating roles of emotions and beliefs about sharing. Health Educ Behav. 2021;48(2):132–9.

Sun S, Hou J, Chen Y, Lu Y, Brown L, Operario D. Challenges to HIV care and psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic among people living with HIV in China. AIDS Behav. 2020;7:1–2.

Wright L, Steptoe A, Fancourt D (2020) How are adversities during COVID-19 affecting mental health? Differential associations for worries and experiences and implications for policy. medRxiv. 2020.05.14.20101717.

Chen B, Sun J, Feng Y. How have COVID-19 isolation policies affected young people’s mental health? – Evidence from Chinese college students. Front Psychol [Internet]. 2020 Jun 24 [cited 2021 Apr 26];11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7327104/

Saltzman LY, Hansel TC, Bordnick PS. Loneliness, isolation, and social support factors in post-COVID-19 mental health. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S55–7.

Matias T, Dominski FH, Marks DF. Human needs in COVID-19 isolation. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(7):871–82.

Giuntella O, Hyde K, Saccardo S, Sadoff S. Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. PNAS [Internet]. 2021 Mar 2 [cited 2021 Apr 26];118(9). https://www.pnas.org/content/118/9/e2016632118

Ellen C, Patricia DV, Miet DL, Peter V, Patrick C, Robby DP, et al. Meaningful activities during COVID-19 lockdown and association with mental health in Belgian adults. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):622.

van der Vegt I, Kleinberg B, et al. Women worry about family, men about the economy: gender differences in emotional responses to COVID-19. In: Aref S, Bontcheva K, Braghieri M, Dignum F, Giannotti F, Grisolia F, et al., editors. Social informatics. Cham: Springer; 2020. p. 397–409.

Wilson JM, Lee J, Fitzgerald HN, Oosterhoff B, Sevi B, Shook NJ. Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62(9):686–91.

Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Balletto BL, Donahue ML, Feulner MM, Cruess DG, Salmoirago-Blotcher E, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for adults living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(1):60–75.

Rogers BG, Coats CS, Adams E, Murphy M, Stewart C, Arnold T, et al. Development of telemedicine infrastructure at an LGBTQ+ clinic to support HIV prevention and care in response to COVID-19, Providence, RI. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(10):2743–7.

Budak JZ, Scott JD, Dhanireddy S, Wood BR. The impact of COVID-19 on HIV care provided via telemedicine—past, present, and future. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2021;18(2):98–104.

Mgbako O, Miller EH, Santoro AF, Remien RH, Shalev N, Olender S, et al. COVID-19, telemedicine, and patient empowerment in HIV care and research. AIDS Behav. 2020;21:1–4.

Sharma AE, Khoong EC, Nijagal MA, Lyles CR, Su G, DeFries T, et al. Clinician experience with telemedicine at a safety-net hospital network during COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021;32(2):220–40.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants and study staff who donated their time to make the MAPLE study possible.

Funding

This study is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant Nos. R01DA042609 and R01DA042609-04S1). C.P is funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant No. T32AA025877).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CP conceptualized the paper, created the qualitative codebook, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; DV conceptualized the paper and contributed to manuscript preparation; YW conceptualized the paper and contributed to manuscript preparation; KV contributed to manuscript preparation; GEI contributed to manuscript preparation; LC analyzed the data and contributed to manuscript preparation; RLC contributed to the study design and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Ethics Approval

The MAPLE study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board and the Florida Department of Health Institutional Review Board, with other participating institutions approving under a reciprocity agreement.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parisi, C.E., Varma, D.S., Wang, Y. et al. Changes in Mental Health Among People with HIV During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Qualitative and Quantitative Perspectives. AIDS Behav 26, 1980–1991 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03547-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03547-8