Abstract

Diseases likely affect large carnivore demography and can hinder conservation efforts. We considered three highly contagious viruses that infect a wide range of domestic and wild mammals: canine parvovirus type 2 (CPV-2), canine distemper virus (CDV) and canine enteric coronaviruses (CECoV). Infection by either one of these viruses can affect populations through increased mortality and/or decreased general health. We investigated infection in the wolf populations of Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise National Park (PNALM), Italy, and of Mercantour National Park (PNM), France. Faecal samples were collected during one winter, from October to March, from four packs in PNALM (n = 79) and from four packs in PNM (n = 66). We screened samples for specific sequences of viral nucleic acids. To our knowledge, our study is the first documented report of CECoV infection in wolves outside Alaska, and of the large-scale occurrence of CPV-2 in European wolf populations. The results suggest that CPV-2 is enzootic in the population of PNALM, but not in PNM and that CECoV is episodic in both areas. We did not detect CDV. Our findings suggest that density and spatial distribution of susceptible hosts, in particular free-ranging dogs, can be important factors influencing infections in wolves. This comparative study is an important step in evaluating the nature of possible disease threats in the studied wolf populations. Recent emergence of new viral strains in Europe additionally strengthens the need for proactive monitoring of wolves and other susceptible sympatric species for viral threats and other impairing infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Disease-induced population decline has been reported in several large carnivore species, and most epidemic events appear to be caused by viruses (Murray et al. 1999). Even when the effects of diseases are not epizootic and are apparently sublethal, pathogens may affect the size or resilience of infected host populations and increase the probability of decline caused by other factors (Cleaveland et al. 2002). When infections are endemic in reservoir hosts and transmitted horizontally among taxa, the threat of disease epidemics in large carnivores can be important, as demographic effects of disease may occur regardless of host population size or disease transmission rate (Murray et al. 1999). Spread of existing and emerging pathogens in free-ranging animals can cause rapid changes in the abundance and genetic diversity of susceptible populations (Altizer et al. 2003).

Canine parvovirus type 2 (CPV-2) and canine distemper virus (CDV) are well-known pathogens of canids and are reported to occur in several free-ranging wolf populations in Europe and around the world (Kreeger 2003; Zarnke et al. 2004; Frölich et al. 2005; Sobrino et al. 2008; Almberg et al. 2009; Santos et al. 2009; Di Sabatino et al. 2014). Infection by Alphacoronaviruses (ACVs) is poorly documented in free-ranging canid populations. The variants of ACVs infecting canids are canine enteric coronaviruses type I and II (CECoV). Canine enteric coronaviruses have been detected in wolves only in Alaska (Zarnke et al. 2001). Nevertheless, this rapidly evolving virus appears to be enzootic worldwide in dogs (Pratelli 2006) and has recently received increased attention in Europe (Benetka et al. 2006; Buonavoglia et al. 2006; Decaro and Buonavoglia 2008; Decaro et al. 2008). Transmission of numerous viruses is highly influenced by local carnivore densities (Murray et al. 1999). Dogs can transmit each of these three pathogens to other carnivores, through direct contact (e.g. saliva) or contact with contaminated material (e.g. faeces, vomitus; Kreeger 2003), and might therefore introduce and/or help maintain infection in susceptible wolf populations.

Canine parvovirus type 2, CDV and CECoV are highly contagious pathogens that can infect a wide range of domestic and free-ranging species (Deem et al. 2000; Buonavoglia et al. 2006; de Oliveira Hübner et al. 2010; Nandi and Kumar 2010). Infection by each of these viruses has been associated with high morbidity and mortality in domestic and free-ranging carnivores including wolves (Johnson et al. 1994; Pence 1995; Gese et al. 1997; Di Sabatino et al. 2014), with usually more severe symptoms reported in young individuals (Murray et al. 1999; Deem et al. 2000; Kreeger 2003; Pratelli 2006; Almberg et al. 2009; Nandi and Kumar 2010; Mech and Goyal 2011). Canine distemper infection typically causes pneumonia, encephalitis and/or diarrhoea (Murray et al. 1999; Deem et al. 2000; Kreeger 2003). Canine parvovirus type 2 and CECoV primarily affect the small intestine, causing sometimes severe enteritis and consequent dehydration (Kreeger 2003; Pratelli 2006; Decaro and Buonavoglia 2008). Additionally, foetal or neonatal infection by CPV-2 can trigger severe myocarditis (Kreeger 2003). Systemic infection by CDV or CECoV may also cause various neurological manifestations (Deem et al. 2000; Kreeger 2003; Buonavoglia et al. 2006). Co-infection by CPV-2 and CECoV is associated with more severe symptoms (Decaro et al. 2006; Pratelli 2006). New variants of each of these three viruses have recently been identified in Italy and in other countries of Western Europe, some of which show increased virulence and increased capacity of horizontal transmission (Buonavoglia et al. 2001, 2006; Evermann et al. 2005; Martella et al. 2005; Decaro and Buonavoglia 2008; Le Poder 2011; Monne et al. 2011; Origgi et al. 2012; Di Sabatino et al. 2014). These variants result from mutations and recombination events in local viruses and possibly also from importation of infected animals from other countries (Benetka et al. 2006; Buonavoglia et al. 2006; Demeter et al. 2007; Allison et al. 2012; Origgi et al. 2012). These shared characteristics of CPV-2, CDV and CECoV make them important conservation threats for susceptible host species. The impact of infection on recolonizing wolf populations might be exacerbated compared to large, well-established populations (Johnson et al. 1994).

Wolves typically live in family-based packs, consisting of a mated pair and their offspring of one or several generations, born in early spring (Packard 2003). The studied wolf subspecies, Canis lupus italicus (Randi et al. 2000), is protected. It is only present in Italy and in recently recolonized areas of the Alps in the neighbouring countries (Valière et al. 2003). The wolf never disappeared from central Italy, where small groups of individuals survived the large-scale extermination of the species in Western Europe (Boitani 2003). Since the protection of the carnivore in the 1970s, the population has been recolonizing the alpine range from the Apennines (Lucchini et al. 2002; Fabbri et al. 2007; Ciucci et al. 2009). In France, the first wolf pack settled in Mercantour National Park (PNM) in 1993, after over 50 years of absence (Houard and Lequette 1993).

Most disease surveys on CPV-2, CDV and CECoV use serological investigations to detect specific antibodies. Antibodies indicate previous exposure to an infectious agent but do not provide information on current infection. The virus rapidly disappears from faecal material once active infection is over. In agreement with this, a previous study in Canada showed 100 % seroprevalence of antibodies against CPV-2 in sampled wolves (n = 18), but absence of the virus in all faecal samples collected from the same population (Stronen et al. 2011). Search for CPV-2 DNA in tissue samples also led to negative results in a large-scale survey of free-ranging carnivores, even though detected antibodies proved previous exposure to the virus in some individuals (Frölich et al. 2005).

Serological investigation on four wolves captured in central Italy in 1993 and 1994 showed previous exposure of four and one individuals to CPV-2 and CDV respectively, whereas no exposure to CECoV has been detected (Fico et al. 1996). Similar results were obtained in captive and free-ranging bears in Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise National Park (PNALM) between 1991 and 1995 (Marsilio et al. 1997). An extended study conducted in Northern Italy in 1994 and 1995 reported the presence of CPV-2 in 3.5 % of the analysed wolf scats (Martinello et al. 1997). A severe CDV outbreak recently spread through part of Europe (Sekulin et al. 2011; Origgi et al. 2012). In Italy, the outbreak was first detected in the north of the country in 2006 and rapidly expanded southwards (Monne et al. 2011). In central Italy, including all around the area of PNALM, the death of 20 wolves was recently attributed to infection by CDV; five of these animals were also infected by CPV-2 (Di Sabatino et al. 2014). In PNM, a study investigated the presence of CPV-2 in the wolf population in 1996 and 1997, but was not able to give conclusive evidence of the presence of the virus (Rossi 2000). To our knowledge, no further large-scale viral disease survey has been conducted on this wolf subspecies. In Italy, high seroprevalence rates of CPV-2, CDV and CECoV were lately reported in domestic (Priestnall et al. 2007) and free-ranging (Corrain et al. 2007) dog populations. Spiss et al. (2012) recently showed high seroprevalence of CECoV in a large-scale study of domestic dogs in Austria.

The emergence of very contagious and highly virulent variants of these viruses in Western Europe highlights the crucial role of surveys in wolves in the concerned areas. Identification of potentially harmful pathogens in susceptible populations is an important first step to evaluate and mitigate their potential impact on population dynamics of free-ranging animals (Murray et al. 1999). Understanding which ecological factors shape the spread and severity of diseases can help control the impact of infections on host populations (Murray et al. 1999). The objectives of our study were (a) to investigate the occurrence and spatial distribution of CPV-2, CDV and CECoV infections in wolves in PNALM (Italy) and PNM (France) and (b) to search for environmental correlates of infection in order to help understand and mitigate the spread of the diseases. We expected that viruses would be less widespread in the wolf population of PNM due to its more recent origin, its lower density and/or lower density and spatial distribution of other susceptible sympatric hosts.

Material and methods

Study areas

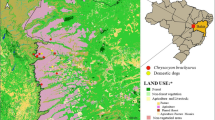

We conducted this survey on wolves in Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise national park (PNALM), in central Italy, and in Mercantour National Park (PNM), in south-eastern France. The wolf populations of these two study areas are connected through a dispersal corridor (Fig. 1). Both study areas are mountainous, partly forested and at similar latitudes (Table 1). Livestock and different wild ungulate species are present year-round in both national parks. The main prey species of wolves vary with the abundance and accessibility of the ungulate species present on the territory of each pack.

Study areas and wolf distribution in 2012, showing the dispersal corridor between Italy and France. Redrawn from Kaczensky et al. (2013)

Mercantour National Park is an area only recently recolonized by wolves. In PNM, the density of the wolf population is low compared to PNALM, from where the carnivore never disappeared. Besides this, the study areas differ in the presence, density and/or spatial distribution of other carnivores susceptible to infection by the investigated viruses: brown bears (Ursus arctos) are present in PNALM but absent from PNM, and dogs are widespread and very common in the Abruzzo region (Boitani and Ciucci 1995; Boitani et al. 2002; Ciucci pers. com.) while rare and mostly localized in restricted areas (around villages) in PNM. In PNALM, a free-ranging dog population is well established in and around the park. Sheepdogs and livestock protection dogs are present in both study areas, especially in summer. Most dogs are vaccinated in PNM (Luddeni pers. com.), but not in PNALM (Ciucci pers. com.).

Investigated packs

We examined spatial distribution of the viruses through sampling of different packs in each national park, considering ≥ two wolves travelling together as a pack. When fieldwork was conducted, seven packs were known to have at least part of their home range within the buffer zone boundaries of both PNALM and PNM (MEEDEM and MAP 2008; Grottoli 2011). Based on the quality and quantity of collected faecal samples, we retained four packs in each national park for our survey (Table 2). The number of animals present in each studied pack was assessed by snow-tracking sessions conducted in winter, complemented in PNM by genetic analyses (Duchamp et al. 2012). In summer, wolf-howling sessions provided data on the reproductive success of these packs (Ciucci and Boitani 2006, 2007; Grottoli 2011; Duchamp et al. 2012). Because samples were collected in winter, they were from individuals of over 6 months of age.

Additionally, we analysed five samples from individuals that dispersed, died or that could not be assigned to one of the packs in PNM, as indicated by genetic analysis of the collected faecal samples (see Miquel et al. 2006; Duchamp et al. 2012 for details). Two of these samples are from the same individual.

Sample collection and identification

In both study areas, wolf scats were collected year round by scientists, local co-workers and rangers (Ciucci and Boitani 2006, 2007; Grottoli 2011; Duchamp et al. 2012) for the purpose of non-invasive molecular tracking or diet analysis. In the present survey, we considered samples collected between the 1st of October 2005 and the 31st of March 2006 in PNM, and between the 1st of October 2006 and the 31st of March 2007 in PNALM. In both study areas, most wolf scats were collected while snow-tracking the studied packs. In the absence of snow cover, samples were collected at known scent posts, at exploited carcasses or during opportunistic surveys along pathways (Grottoli 2011; Duchamp et al. 2012).

In PNALM, multiple criteria were used to conservatively discriminate wolf scats from those of other species, among which a diameter ≥2.5 cm and estimated volume ≥100 cc (Ciucci and Boitani 1998; Grottoli 2011). Based on mtDNA and nuclear markers (Boggiano et al. 2013), all fresh scats (n = 107) collected on the snow along wolf trajectories from December 2005 to March 2006 in this study area were from wolves, except for two samples from foxes. This provides a direct validation (98 % accuracy) of the selection criteria adopted (Ciucci pers. com.).

In PNM, genetic data based on a set of seven microsatellite loci were available from previous pilot studies in France. These allowed the discrimination of wolf scats from those of other species (Valière et al. 2003) and the identification of the sex and identity of most contributing animals by the detection of individual genotypes from faecal samples (see Miquel et al. 2006; Duchamp et al. 2012 for details).

We analysed only well preserved samples. We did not retain for analysis faecal samples that were partly consumed by birds, dried out, or exposed to rain or to temperatures obviously above freezing point. We excluded samples composed mostly of hair (estimated as >90 % of the scat volume), as well as scats over-marked with urine or lying less than 50 cm away from another scat. On the day of collection, all samples were stored at −20 °C in labelled plastic bags and kept frozen until analysis.

Nucleic acid screening and sequence analysis

To assess effective infection by the viruses, and not only exposure of the individuals, we screened collected scats for specific sequences of viral nucleic acids. Before extraction of nucleic acids, samples were vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged at 4,000×g for 10 min; 140 μl served as template using a commercially available kit (QIAamp viral RNA Kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, suitable to extract viral RNA as well as DNA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracts were stored at −80 °C.

Detection of CDV specific RNA was carried out with the primers PP-I p1 and p2 described by Frisk et al. (1999). RT-PCR assays were run in a volume of 20 μl (18.4 μl reaction mixture, OneStep RT-PCR Kit, Qiagen; 1.6 μl template) and a primer concentration of 0.4 μM. The thermocycler scheme consisted of two pre-PCR steps of 50 °C, 30 min and 94 °C, 15 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (94 °C, 30 s), annealing (58 °C, 30 s) and extension (72 °C, 1 min) and a final extension (72 °C, 10 min). For the detection of CECoV specific nucleic acids (member of genus Alphacoronavirus) realtime-PCR was performed using the primers and probe described by Gut et al. (1999), who indicate a high cross-reactivity among Alphacoronaviruses. Canine parvovirus type 2 specific nucleic acids were detected by realtime-PCR with primers and probe described by Decaro et al. (2005). Negative controls, consisting only of the components of the kit, were run together with the samples through all procedure steps. Equivocal results were not considered in the interpretation of data.

Sequencing was performed on 409 bp of the CCoV gene (primers CCoV1 and CCoV2 according to Pratelli et al. 2002) and 683 bp of the CPV-2 gene (primers F/CPV-2F: 5′-ATGGAGCAGTTCAACCAGAC-3′ and F/CPV-2R: 5′-TGTTGGTGTGCCACTAGTTC-3′). Amplified DNA was extracted using a commercially available kit (QIAquick® PCR purification kit) following the manufacturer’s instructions and served as template for sequencing PCR, which was carried out in a volume of 20 μl with a ready to use sequencing PCR mixture (DNA Sequencing Kit). Forward and reverse sequences of PCR products were analysed using ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyser.

Prevalence and confidence interval

Prevalence refers to NPos/N, with NPos the number of wolf scats in which viral nucleic acids of CPV-2, CDV or CECoV were detected, and N the total number of samples analysed for the considered virus within each study area. As not all scats are statistically independent (i.e. multiple analysed faecal samples are from the same individuals), calculated prevalence does not represent prevalence of the virus in the populations and cannot be interpreted as such. However, we used these values in a simple comparison of the study areas. We calculated confidence intervals (95 %) following a binomial distribution for large sample (Sokal and Rohlf 1995), using R 2.15 (R Core Team 2013).

Results

We analysed 79 wolf faecal samples from PNALM and 66 from PNM, collected from four packs in each study area (Table 3). In PNM, we also analysed five samples from individuals that could not be assigned to a pack, dispersed or died. In order to confirm specificity, we analysed randomly selected sequences of five CPV-2 and two CECoV positive samples. The homology between the five CPV-2 sequences was 99.5–100 % and 99 to 99.3 % to CPV-2 strain C-780916 (American Type Culture Collection ATCC VR-953). The sequences of the two CECoV positive samples were up to 98–99 % homolog to various CECoV sequences available in GenBank (EU856361.1, DQ112226.1, EU924791.1 and EU924790.1).

We identified CPV-2 in all four packs in PNALM (n = 12, prevalence = 15.2 %) and in two different packs in PNM (n = 8, prevalence = 12.1 %; Table 3). In PNM, all positive samples but one were from the Haute Tinée pack, in which the two females and the one male all shed CPV-2 DNA in their faeces. Another positive sample was from a male in the Vésubie-Tinée pack. We detected CECoV in two packs in PNALM (n = 7, prevalence = 8.9 %) and one pack as well as two other individuals in PNM (n = 4, prevalence = 6.1 %). In PNM, positive samples from identified individuals were from the Haute Tinée pack (n = 1) and a dispersing male (n = 2). We did not detect nucleic acids of CDV in the analysed samples.

We detected both CPV-2 and CECoV in two samples from the Italian Villavalelonga pack. Considering infections at the pack level, we detected both CPV-2 and CECoV in two packs in PNALM and in one pack in PNM (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study is the first large-scale multi-viral infection survey conducted on wolves in Italy or in France through non-invasive techniques and is among the rare investigations on wolves in Western Europe (Martinello et al. 1997; Sobrino et al. 2008; Santos et al. 2009; Di Sabatino et al. 2014). To our knowledge, our findings are the first reported CECoV infections in wolves outside Alaska. Although exposure of wolves to CPV-2 was previously reported in France (based on a few opportunistic necropsies of dead animals; Duchamp and Gauthier, unpublished data) and in Italy (Fico et al. 1996; Martinello et al. 1997; Di Sabatino et al. 2014), our study provides the first conclusive evidence of CPV-2 infection in several established wolf packs in these two countries. Previous opportunistic testing of animals found dead revealed no infection by CDV or CECoV in French wolves, whereas similar investigations recently detected CDV in wolves around PNALM (Di Sabatino et al. 2014). Given the possible negative impact of these viruses on canid populations, and because only little information is available on C. lupus italicus, the results from our study are important for conservation management and highlight the need for continued monitoring.

We used molecular investigations to detect viral nucleic acids in faecal samples from PNM and PNALM. Whereas this technique is unable to detect previous exposure as indicated by specific anti-viral antibodies, it detects recent infection of individuals (Martinello et al. 1997; Murray et al. 1999). The same molecular techniques were used for each virus and analyses were undertaken in a single laboratory, ensuring consistency of results and thus enabling direct comparison of the two studied populations. As most previous studies investigated exposure to viruses through serological surveys, derived findings cannot be directly compared with our results.

Close physical contact between group members is characteristic of social canids such as wolves and greatly enhances within-pack transmission of pathogens (Johnson et al. 1994). Pack members regularly use urine and faeces to mark their territory (Harrington and Asa 2003) and inspection of faecal markings is frequent along territory edges. Investigation of the ano-genital area of conspecifics is part of common social interactions (Harrington and Asa 2003). These behavioural characteristics of wolves enhance oro-faecal transmission of pathogens between individuals. Therefore, and given that these viruses are highly contagious, the detection of CPV-2 or CECoV in one or more samples from a pack suggests that several members of that pack were probably infected. Thus, we discuss our results mostly based on the infection at the pack-level.

The wolf populations of PNALM and PNM are connected through a dispersal corridor (Ciucci et al. 2009; Falcucci et al. 2013) since over 20 years, and the region separating the two study areas is home to several widely distributed alternative susceptible host species (e.g. the red fox—Vulpes vulpes). Therefore, similar infection rates of wolves by the highly contagious studied viruses could be expected in the two areas. However, differences between PNALM and PNM in the density of wolves as well as the presence and density of other susceptible host species may be important ecological factors shaping the distribution of viruses in the environment, and consequently, the exposure of wolves to these pathogens. In particular, the spatial distribution of dogs, widespread in PNALM while more localized in PNM, may play a specific role in the transmission of diseases to wolves. In PNALM, an unvaccinated free-ranging dog population lives sympatrically with the studied wolf packs. In the Mercantour area, numerous farm dogs and hunting dogs are reported seropositive to CPV-2, as recorded by local veterinarians (Luddeni pers. com.). This can however be the consequence of vaccination or exposure to the virus in the environment. Among the four studied French packs, the territory of the Haute Tinée pack is the only one that contains a major village in its centre, which may enhance contact rates between wolves and contaminated faeces from domestic dogs. The territory of this pack also lies along one of the main roads crossing the Alps, and is used by many travellers and their pet dogs. Such important anthropogenic influences acting in this specific area may favour transmission of pathogens to wolves through contamination of the environment by domestic dogs, and could explain the detection of both CPV-2 and CECoV in the Haute Tinée pack.

Canine parvovirus type 2

Prevalence of CPV-2 in wolf faecal samples ranged from 12.1 % to 15.2 % in PNM and PNALM respectively. Identification of CPV-2 in all investigated packs of PNALM suggests that the virus is enzootic in that wolf population (Almberg et al. 2009; Mech and Goyal 2011). In PNM, however, CPV-2 was only detected in two packs out of four, indicating that the virus may not yet be established in the whole population.

Although the density of various species susceptible to infection by CPV-2 might be similar in both study areas, the population of free-ranging dogs only present in PNALM may play a significant role in the dissemination of CPV-2 in the environment. Brown bears are also absent from PNM, whereas individuals infected by CPV-2 have been reported in PNALM (Marsilio et al. 1997). Thus, even though CPV-2 is highly resistant (Steinel et al. 2001), contamination of the environment by the virus may be limited in PNM because of a lower density and/or distribution range of other susceptible hosts as compared to PNALM.

Canine enteric coronaviruses

As the Alphacoronaviruses (ACVs) group comprises porcine enteric coronaviruses (Decaro and Buonavoglia 2008), the detection, in our study, of ACVs from infected wild boars consumed by wolves cannot be excluded. Indeed, these ungulates are prey species of the carnivore in PNALM (Grottoli 2011) and in PNM. However, only very low prevalence of infection by ACVs is reported in wild boars in Europe (Vengust et al. 2006; Ruiz-Fons et al. 2008; Sedlak et al. 2008; Kaden et al. 2009), and dilution of viral particles in wolf faeces would further decrease chances of detection. Additionally, our sequencing of randomly selected positive samples from PNALM and PNM indicated specificity for CECoV.

High density of susceptible host populations (Zarnke et al. 2001) and frequent social interactions with conspecifics (Priestnall et al. 2007) enhance transmission opportunities of CECoV. We identified this virus in two packs in PNALM and one pack in PNM. That CECoV was not detected in all packs suggests that the virus is not enzootic in these wolf populations. Coronaviruses are inactivated in a few days at 37 °C, but remain infective for up to several months at 4 °C and below (Pratelli 2008). In their serological survey of a wolf population, Zarnke et al. (2001) reported that CECoV might mainly be transmitted in wintertime. They also showed that immunity against CECoV seems to be short-lived and disappears rapidly without re-exposure to the virus. Therefore, our results suggest that CECoV is better maintained in the high-density multi-host populations in PNALM and/or that the virus is recurrently introduced into the wolf population by sympatric susceptible hosts. In Italy, exposure of dogs to CECoV is widespread and frequently reported (Pratelli et al. 2003; Priestnall et al. 2007; Decaro and Buonavoglia 2008; Decaro et al. 2008). Thus, the free-ranging dog population of PNALM may serve as a reservoir for the infection or reinfection of wolves by this virus.

Co-infection by CPV-2 and CECoV

Co-infection by CPV-2 and CECoV is known to enhance the severity of symptoms (Evermann et al. 2005; Decaro et al. 2006; Pratelli 2006), and fatal outcomes have been reported in dog pups (Decaro et al. 2006). In PNALM, we detected both CECoV and CPV-2 in two packs and found concurrent infection by both viruses in samples collected in one of them. In the Italian packs, young pup mortality typically caused by CPV-2 and CECoV co-infection did however not result in early loss of entire litters. Once CPV-2 becomes enzootic in a population, its negative impact on pup survival seems to decline (Mech and Goyal 2011). The development of long-lasting, possibly life-long, immunity following CPV-2 infection (Steinel et al. 2001; Mech and Goyal 2011) may have a protective effect on the wolf population of PNALM, and help explain the reproductive success in all four packs, despite the detection of CPV-2 and CECoV in two of them. In PNM, we found both CECoV and CPV-2 only in the Haute Tinée pack, with no sample containing both viruses. Possibly, fatal co-infection with CPV-2 and CECoV can be a determinant factor explaining the absence of surviving pups in the Haute Tinée pack in the summer following that of samples collection. We however also know that one of the mating partners disappeared from the pack during the winter of investigation. Despite the subsequent detection of a new individual in this pack before the onset of the mating season, it is unclear whether this new pack member replaced the missing partner.

As our results suggest that CPV-2 is not enzootic in the wolf population of PNM, individuals may be more vulnerable to CPV-2 infection as well as to co-infection by CPV-2 and CECoV. This may have contributed to the low detected pup production in two consecutive summers in PNM (2005 and 2006) compared to PNALM (2006 and 2007).

Canine distemper virus

Serological surveys conducted 15 years ago reported exposure to CDV in three out of nine free-ranging brown bears (Marsilio et al. 1997) in PNALM, and in one out of four wolves in a neighbouring geographical area (Fico et al. 1996). Exposure of foxes and badgers to CDV was also documented in the same general area (Di Sabatino et al. 2014). As none of the samples that we analysed tested positive for CDV, our results suggest that the virus was absent from the investigated wolf populations at the time of sample collection. However, that infected individuals typically shed the virus only for 4 to 5 days in their faeces minimizes the chance to detect the pathogen, even from sick animals.

Broad implications

Negative impact of diseases on population dynamics is underestimated, as morbidity and mortality are difficult to evaluate in free-ranging populations (Zarnke et al. 2004). This applies even more to large carnivores, owing to their secretive behaviour (Murray et al. 1999). The extent of the impact depends on the proportions of additive and compensatory diseases-caused mortalities. In social species such as wolves, mortality caused by infections can, however, also affect other important biological parameters, as the social structure of groups.

Infection by either one of the viruses considered in the present study can have considerable effects on population dynamics of susceptible canids through increased mortality and/or decreased general health, and consequently impact dispersal in free-ranging populations (Johnson et al. 1994; Kreeger 2003; Pratelli 2006; Almberg et al. 2009; Nandi and Kumar 2010; Mech and Goyal 2011; Monne et al. 2011; Prager et al. 2012). Large-scale disease surveys are yet seldom undertaken in European wild carnivores. Disease-induced mortality and morbidity in the long-established and saturated wolf population of PNALM can have consequences on a larger scale, slowing down the dispersal dynamic of the species and thus directly affecting the connected and expanding populations.

Our results indicate that CECoV should be widely included in epidemiological surveys in free-ranging canids. Given that CECoV remains infective for extended periods of time at cold temperatures (Pratelli 2008), this virus might represent a more significant conservation concern in boreal and/or mountain ecosystems experiencing yearly winters conditions. In Europe, this applies to most northern countries and to mountainous areas located at higher elevations, as the Alps and the Apennines.

In the future, the contact between large carnivores and domestic animals, and thus the risks of infectious disease transmission, will probably increase as the consequence of range overlap (Murray et al. 1999) resulting from habitat fragmentation (Cleaveland et al. 2002). Pathogens infecting multiple taxa and those that are highly contagious will be of highest conservation concern (Murray et al. 1999). Wild canids are at specific risk of exposure to diseases, as they share susceptibility to numerous pathogens with the dog, the most abundant carnivore (Randall et al. 2004). Among others, it has been suggested that dogs might be a reservoir for the infection of wild canids by CPV-2, CECoV and CDV (Corrain et al. 2007; Prager et al. 2012; Di Sabatino et al. 2014). This may also be the case for CPV-2 and CECoV infections in wolves in PNALM and PNM. Indeed, when comparing our two study areas, global prevalence of both CPV-2 and CECoV is similar, but the spatial distribution of infection in the packs differs: It is consistent with the presence of dogs, widely distributed in PNALM whereas more localized around villages in PNM. The large population of unvaccinated free-ranging dogs present in Italy (Verardi et al. 2006; Corrain et al. 2007) considerably increases the density of susceptible hosts, and may thus importantly impact the spread and maintenance of canid pathogens in the environment. A study of the feral dog population of Abruzzo, which includes PNALM (Boitani and Ciucci 1995), supports this hypothesis. It reports very low survival rate of pups (30 % and 7.5 % at 70 days and 4 months of age, respectively), and population demography mostly driven by stochastic mechanisms. Such observations could well be explained by infection or co-infection by the viruses considered in our study, and suggest that sympatric dogs may play a significant role in the infection of wolves. As foxes and dogs, jackals are susceptible to infection by canid pathogens including CECoV (Goller et al. 2012) and are even reported reservoirs hosts of CPV-2 and CVD (Aguirre 2009). As the golden jackal (Canis aureus) is extending its range in Europe and recently reached northern Italy (Arnold et al. 2012), this additional susceptible host might play an increasing role in the spread of the studied viruses in Europe.

The non-invasive sample collection used in this work is well adapted to our study of free-ranging wolf populations. Additionally, scats collected in winter provide the most representative data, as snow-tracking procedures potentially give access to samples from each individual, independent of the marking behaviour characteristics of pack leaders (Verardi et al. 2006).

Conclusion

Highly contagious pathogens with important potential for horizontal transmission will be of increasing concern for the conservation of carnivores. Our findings suggest that CPV-2 is enzootic in the wolf population of PNALM but not in PNM, and that CECoV is episodic in both areas. In each study area, infection detected in packs was consistent with the spatial distribution of dogs, which may play an important role in the infection of wolves. We therefore strongly recommend the vaccination of domestic and working dogs, as well as of stray dogs whenever possible. The recently established wolf population of PNM may be more vulnerable to viral infections and less resilient to epizootic events than the long-established population of PNALM. On the other hand, the wolf population of PNALM is at increased risk of exposure to emerging strains of highly virulent viruses, as transmission is more likely in high-density susceptible multi-host populations. Infections in the source population of PNALM can have a direct negative impact on connected recolonizing populations, through decreased survival and dispersal. Future large-scale infectious disease surveys, both in wolves and in other susceptible sympatric species, would help understand the epidemiological and spatiotemporal patterns of infections.

To take potentially harmful diseases into account may also importantly refine demographic modelling of free-ranging large carnivore populations and sharpen our understanding of the population dynamics of these species. Our findings strongly suggest that prospective large-scale longitudinal surveys are essential to monitor and evaluate the spread of viruses, of both established and new strains, and their consequences on the studied populations. They underline the necessity for continued monitoring of viral and other infectious diseases, in conservation programs and in local as well as global management strategies of wolves and other carnivores, as an important first step in attempting to mitigate the impact of infections on wild populations.

References

Aguirre AA (2009) Wild canids as sentinels of ecological health: a conservation medicine perspective. Parasite Vectors. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-2-S1-S7

Allison AB, Harbison CE, Pagan I, Stucker KM, Kaelber JT, Brown JD, Ruder MG, Keel MK, Dubovi EJ, Holmes EC, Parrish CR (2012) Role of multiple hosts in the cross-species transmission and emergence of a pandemic parvovirus. J Virol 86:865–872

Almberg ES, Mech LD, Smith D, Sheldon JW, Crabtree RL (2009) A serological survey of infectious disease in Yellowstone National Park’s canid community. PLoS ONE 4:1–11

Altizer S, Harvell D, Friedle E (2003) Rapid evolutionary dynamics and disease threats to biodiversity. Trends Ecol Evol 18:589–596

Arnold J, Humer A, Heltai M, Murariu D, Spassov N, Hackländer K (2012) Current status and distribution of golden jackals Canis aureus in Europe. Mammal Rev 42:1–11

Benetka V, Kolodziejek J, Walk K, Rennhofer M, Möstl K (2006) M gene analysis of atypical strains of feline and canine coronavirus circulating in an Austrian animal shelter. Vet Rec 159:170–175

Boggiano F, Ciofi C, Boitani L, Formia A, Grottoli L, Natali C, Ciucci P (2013) Detection of an East European wolf haplotype puzzles mitochondrial DNA monomorphism of the Italian wolf population. Mamm Biol—Z Säugetierkd 78:374–378

Boitani L (2003) Wolf conservation and recovery. In: Mech LD, Boitani L (eds) Wolves: behavior, ecology, and conservation. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 317–340

Boitani L, Ciucci P (1995) Comparative social ecology of feral dogs and wolves. Ethol Ecol Evol 7:49–72

Boitani L, Francisci F, Ciucci P, Andreoli G (2002) Population biology and ecology of feral dogs in central Italy. In: Serpell J (ed) The dog: its ecology, behaviour and evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 217–244

Buonavoglia C, Martella V, Pratelli A, Tempesta M, Cavalli A, Buonavoglia D, Bozzo G, Elia G, Decaro N, Carmichael L (2001) Evidence for evolution of canine parvovirus type 2 in Italy. J Gen Virol 82:3021–3025

Buonavoglia C, Decaro N, Martella V, Elia G, Campolo M, Desario C, Castagnaro M, Tempesta M (2006) Canine coronavirus highly pathogenic for dogs. Emerg Infect Dis 12:492–494

Ciucci P, Boitani L (1998) Il Lupo. Elementi di biologia, gestione e ricerca. Istituto Nazionale della Fauna Selvatica “Alessandro Ghigi”, Documenti Tecnici 23 [In Italian]

Ciucci P, Boitani L (2006) Conservation of large carnivores in Abruzzo: a research project integrating species, habitat and human dimension. Annual Report 2006. Wildlife Conservation Society, New York—University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Ciucci P, Boitani L (2007) Conservation of large carnivores in Abruzzo: a research project integrating species, habitat and human dimension. Annual Report 2007. Wildlife Conservation Society, New York—University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Ciucci P, Boitani L (2008) Conservation of large carnivores in Abruzzo: a research project integrating species, habitat and human dimension. Annual report 2008. Wildlife Conservation Society, New York—University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Ciucci P, Reggioni W, Maiorano L, Boitani L (2009) Long-distance dispersal of a rescued wolf from the Northern Apennines to the Western Alps. J Wildl Manag 73:1300–1306

Cleaveland SG, Hess R, Dobson AP, Laurenson MK, McCallum HI, Roberts MG, Woodroffe R (2002) The role of pathogens in biological conservation. In: Hudson PJ, Rizzoli A, Grenfell BT, Heesterbeek H, Dobson AP (eds) The ecology of wildlife diseases. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 139–150

Corrain R, Di Francesco A, Bolognini M, Ciucci P, Baldelli R, Guberti V (2007) Serosurvey for CPV-2, distemper virus, ehrlichiosis and leishmaniosis in free-ranging dogs in Italy. Vet Rec 160:91–92

de Oliveira Hübner S, Geraldes Pappen F, Lopes Ruas J, D’Ávila Vargas G, Fischer G, Vidor T (2010) Exposure of pampas fox (Pseudalopex gymnocercus) and crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) from southern region of Brazil to canine distemper virus (CDV), canine parvovirus (CPV) and canine coronavirus (CECoV). Braz Arch Biol Technol 53:593–597

Decaro N, Buonavoglia C (2008) An update on canine coronaviruses: viral evolution and pathobiology. Vet Microbiol 132:221–234

Decaro N, Elia G, Martella V, Desario C, Campolo M, Di Trani L, Tarsitano E, Tempesta M, Buonavoglia C (2005) A real-time PCR assay for rapid detection and quantification of canine parvovirus type 2 in the feces of dogs. Vet Microbiol 105:19–28

Decaro N, Martella V, Desario C, Bellacicco AL, Camero M, Manna L, D’Aloja D, Buonavoglia C (2006) First detection of canine parvovirus type 2c in pups with haemorrhagic enteritis in Spain. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health 53:468–472

Decaro N, Campolo M, Lorusso A, Desario C, Mari V, Colaianni ML, Elia G, Martella V, Buonavoglia C (2008) Experimental infection of dogs with a novel strain of canine coronavirus causing systemic disease and lymphopenia. Vet Microbiol 128:253–260

Deem SL, Spelman LH, Yates RA, Montali RJ (2000) Canine distemper in terrestrial carnivores: a review. J Zoo Wildl Med 31:441–451

Demeter Z, Lakatos B, Palade EA, Kozma T, Forgách P, Rusvai M (2007) Genetic diversity of Hungarian canine distemper virus strains. Vet Microbiol 122:258–269

Di Sabatino D, Lorusso A, Di Francesco CE, Gentile L, Di Pirro V, Bellacicco AL, Giovannini A, Di Francesco G, Marruchella G, Marsilio F, Savini G (2014) Arctic lineage-canine distemper virus as a cause of death in Apennine wolves (Canis lupus) in Italy. PLoS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082356

Duchamp C, Boyer CJ, Briaudet PE, Léonard Y, Moris P, Bataille A, Dahier T, Delacour G, Millisher G, Miquel C, Poillot C, Marboutin E (2012) A dual frame survey to assess time- and space-related changes of the colonizing wolf population in France. Hystrix Ital J Mammal 23:14–28

Evermann JF, Abbott JR, Han S (2005) Canine coronavirus-associated puppy mortality without evidence of concurrent canine parvovirus infection. J Vet Diagn Investig 17:610–614

Fabbri E, Miquel C, Lucchini V, Santini A, Caniglia R, Duchamp C, Weber JM, Lequette B, Marucco F, Boitani L, Fumagalli L, Taberlet P, Randi E (2007) From the Apennines to the Alps: colonization genetics of the naturally expanding Italian wolf (Canis lupus) population. Mol Ecol 16:1661–1671

Falcucci A, Maiorano L, Tempio G, Boitani L, Ciucci P (2013) Modeling the potential distribution for a range-expanding species: wolf recolonization of the Alpine range. Biol Conserv 158:63–72

Fico R, Marsilio F, Tiscar PG (1996) Indagine sulla presenza di anticorpi contro il virus della parvovirosi canina, del cimurro, dell’epatite infettiva del cane, il coronavirus del cane e l’Ehrlichia canis in sieri di Lupo (Canis lupus) dell’Italia centrale. In: Spagnesi M, Guberti V, De Marco MA (eds) Atti del Convegno Nazionale: Ecopatologia della Fauna Selvatica. Suppl Ric Biol Selvaggina 24:137–143 [In Italian]

Frisk AL, König M, Moritz A, Baumgärtner M (1999) Detection of canine distemper virus nucleoprotein RNA by reverse transcription-PCR using serum, whole blood and cerebrospinal fluid from dogs with distemper. J Clin Microbiol 37:3634–3643

Frölich K, Streich WJ, Fickel J, Jung S, Truyen U, Hentschke J, Dedek J, Prager D, Latz N (2005) Epizootiologic investigations of parvovirus infections in free-ranging carnivores from Germany. J Wildl Dis 41:231–235

Gese EM, Schultz RD, Johnson MR, Williams ES, Crabtree RL, Ruff RL (1997) Serological survey for diseases in free-ranging coyotes (Canis latrans) in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. J Wildl Dis 33:47–56

Goller KV, Fickel J, Hofer H, Beier S, East ML (2012) Coronavirus genotype diversity and prevalence of infection in wild carnivores in the Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. Arch Virol. doi:10.1007/s00705-012-1562-x

Grottoli L (2011) Assetto territoriale ed ecologia alimentare del lupo (Canis lupus) nel Parco Nazionale d’Abruzzo Lazio e Molise. Dissertation, University of Rome “La Sapienza” [In Italian, with abstract and legends in English]

Gut M, Leutenegger CM, Huder JB, Pedersen NC, Lutz H (1999) One-tube fluorogenic reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for the quantitation of feline coronaviruses. J Virol Methods 77:37–46

Harrington FH, Asa CS (2003) Wolf communication. In: Mech LD, Boitani L (eds) Wolves: behavior, ecology, and conservation. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 66–103

Houard T, Lequette B (1993) Le retour des loups dans le Mercantour. Riviera Sci 11:61–66

Johnson MR, Boyd DK, Pletscher DH (1994) Serologic investigations of canine parvovirus and canine distemper in relation to wolf (Canis lupus) pup mortalities. J Wildl Dis 30:270–273

Kaczensky P, Chapron G, von Arx M, Huber D, Andrén H, Linnell J (eds) (2013) Status, management and distribution of large carnivores—bear, lynx, wolf & wolverine—in Europe. Document prepared with the assistance of Istituto di Ecologia Applicata and with the contributions of the IUCN/SSC Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe under contract N°070307/2012/629085/SER/B3 for the European Commission. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/carnivores/conservation_status.htm. Accessed 18 Dec 2013

Kaden V, Lange E, Hänel A, Hlinak A, Mewes L, Hergarten G, Irsch B, Dedek J, Bruer W (2009) Retrospective serological survey on selected viral pathogens in wild boar populations in Germany. Eur J Wildl Res 55:153–159

Kreeger TJ (2003) The internal wolf: physiology, pathology, and pharmacology. In: Mech LD, Boitani L (eds) Wolves: behavior, ecology, and conservation. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 192–217

Le Poder S (2011) Feline and canine coronaviruses: common genetic and pathobiological features. Adv Virol. doi:10.1155/2011/609465

Lucchini V, Fabbri E, Marucco F, Ricci S, Boitani L, Randi E (2002) Noninvasive molecular tracking of colonizing wolf (Canis lupus) packs in the Western Italian Alps. Mol Ecol 11:857–868

Marsilio F, Tiscar PG, Gentile L, Roth HU, Boscagli G, Tempesta M, Gatti A (1997) Serological survey for selected viral pathogens in brown bears from Italy. J Wildl Dis 33:304–307

Martella V, Decaro N, Elia G, Buonavoglia C (2005) Surveillance activity of canine parvovirus in Italy. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health 52:312–315

Martinello F, Galuppo F, Ostranello F, Guberti V, Prosperi S (1997) Detection of canine parvovirus in wolves from Italy. J Wildl Dis 33:628–631

Mech LD, Goyal SM (2011) Parsing demographic effects of canine parvovirus on a Minnesota wolf population. J Vet Med Anim Health 3:27–30

MEEDEM, MAP (2008) Plan d’action national sur le loup 2008–2012, dans le contexte français d’une activité importante et traditionnelle d’élevage. Ministère de l’Ecology et Ministère de l’Agriculture (eds). France [In French]

Miquel C, Bellemain C, Poillot C, Bessière J, Durand A, Taberlet P (2006) Quality indexes to assess the reliability of genotypes in studies using non-invasive sampling and multi-tube approach. Mol Ecol Notes 6:985–988

Monne I, Fusaro A, Valastro V, Citterio C, Dalla Pozza M, Obber F, Trevisiol K, Cova M, De Benedictis P, Bregoli M, Capua I, Cattoli G (2011) A distinct CDV genotype causing a major epidemic in Alpine wildlife. Vet Microbiol 150:63–69

Murray DL, Kapke CA, Evermann JF, Fuller TK (1999) Infectious disease and the conservation of free-ranging large carnivores. Anim Conserv 2:241–254

Nandi S, Kumar M (2010) Canine parvovirus: current perspective. Indian J Virol 21:31–44

ONCFS Réseau Loup/Lynx (2005) Bilan du suivi estival par hurlements provoqués. In: ONCFS Réseau grands carnivores loup-lynx (ed) Quoi de Neuf?—Bulletin d’information du réseau loup 14:15–17 [In French]

ONCFS Réseau Loup/Lynx (2006) Résultats du suivi hivernal 2005/2006. In: ONCFS Réseau grands carnivores loup-lynx (ed) Quoi de Neuf?—Bulletin d’information du réseau loup 15:13–17 [In French]

ONCFS Réseau Loup/Lynx (2007) Bilan du suivi hivernal 2006–2007. In: ONCFS Réseau grands carnivores loup-lynx (ed) Quoi de Neuf?—Bulletin d’information du réseau loup 17:10–14 [In French]

Origgi FC, Plattet P, Sattler U, Robert N, Casaubon J, Mavrot F, Pewsner M, Wu N, Giovannini S, Oevermann A, Stoffel MH, Gaschen V, Segner H, Ryser-Degiorgis MP (2012) Emergence of canine distemper virus strains with modified molecular signature and enhanced neuronal tropism leading to high mortality in wild carnivores. Vet Pathol. doi:10.1177/0300985812436743

Packard JM (2003) Wolf behavior: reproductive, social, and intelligent. In: Mech LD, Boitani L (eds) Wolves: behavior, ecology, and conservation. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 35–65

Pence DB (1995) Disease and coyotes in Texas. Wildlife Damage Management, Symposium Proceedings—Coyotes in the southwest: a compendium of our knowledge. pp 17–22

Prager KC, Mazet JAK, Munson L, Cleaveland S, Donnelly CA, Dubovi EJ, Szykman-Gunther M, Lines R, Mills G, Davies-Mostert HT, McNutt JW, Rasmussen G, Terio K, Woodroffe R (2012) The effect of protected areas on pathogen exposure in endangered African wild dog (Lycaon pictus) populations. Biol Conserv 150:15–22

Pratelli A (2006) Genetic evolution of canine coronavirus and recent advances in prophylaxis. Vet Res 37:91–200

Pratelli A (2008) Canine coronavirus inactivation with physical and chemical agents. Vet J 177:71–79

Pratelli A, Tinelli A, Decaro N, Camero M, Elia G, Gentile A, Buonavoglia C (2002) PCR assay for the detection and the identification of atypical canine coronavirus in dogs. J Virol Methods 106:209–213

Pratelli A, Martella V, Decaro N, Tinelli A, Camero M, Cirone F, Elia G, Cavalli A, Corrente M, Greco G, Buonavoglia D, Gentile M, Tempesta M, Buonavoglia C (2003) Genetic diversity of a canine coronavirus detected in pups with diarrhea in Italy. J Virol Methods 110:9–17

Priestnall SL, Pratelli A, Brownlie J, Erles K (2007) Serological prevalence of canine respiratory coronavirus in Southern Italy and epidemiological relationship with canine enteric coronavirus. J Vet Diagn Investig 19:176–180

R Core Team (2013) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 19 Feb 2013

Randall DA, Williams SD, Kuzmin IV, Rupprecht CE, Tallents LA, Tefera Z, Argaw K, Shiferaw F, Knobel DL, Sillero-Zubiri C, Laurenson MK (2004) Rabies in endangered Ethiopian wolves. Emerg Infect Dis 10:2214–2217

Randi E, Lucchini V, Fjeldsø Christensen M, Mucci N, Funk SM, Dolf G, Loeschcke V (2000) Mitochondrial DNA variability in Italian and East European wolves: detecting the consequences of small population size and hybridization. Conserv Biol 14:464–473

Rossi S (2000) Impact des virus pathogènes sur les petites populations de carnivores sauvages: cas du parvovirus canin CPV-2 chez le loup (Canis lupus) du Mercantour. Dissertation, Ecole nationale vétérinaire de Lyon, France [In French]

Ruiz-Fons F, Segalés J, Gortázar C (2008) A review of viral diseases of the European wild boar: effects of population dynamics and reservoir role. Vet J 176:158–169

Santos N, Almendra C, Tavares L (2009) Serologic survey for canine distemper virus and canine parvovirus in free-ranging wild carnivores from Portugal. J Wildl Dis 45:221–226

Sedlak K, Bartova E, Machova J (2008) Antibodies to selected viral disease agents in wild boars from the Czech Republic. J Wildl Dis 44:777–780

Sekulin K, Hafner-Marx A, Kolodziejek J, Janik D, Schmidt P, Nowotny N (2011) Emergence of canine distemper in Bavarian wildlife associated with a specific amino acid exchange in the heamagglutinin protein. Vet J 187:399–401

Sobrino R, Arnal MC, Luco DF, Gortázar C (2008) Prevalence of antibodies against canine distemper virus and canine parvovirus among foxes and wolves from Spain. Vet Microbiol 126:251–256

Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ (1995) Introduction to probability distribution: binomial and poisson. In: Biometry: the principles and practice of statistics in biological research, 3rd edn. Freeman WH and Co, New York, pp 61–97

Spiss S, Benetka V, Künzel F, Sommerfeld-Stur I, Walk K, Latif M, Möstl K (2012) Enteric and respiratory coronavirus infections in Austrian dogs: serological and virological investigations of prevalence and clinical importance in respiratory and enteric disease. Wien Tierazt Monatsschr—Vet Med Austria 99:67–81

Steinel A, Parrish CR, Bloom ME, Truyen U (2001) Parvovirus infections in wild carnivores. J Wildl Dis 37:594–607

Stronen AV, Sallows T, Forbes GJ, Wagner B, Paquet P (2011) Diseases and parasites in wolves of the Riding Mountain National Park region, Manitoba, Canada. J Wildl Dis 47:222–227

Valière N, Fumagalli L, Gielly L, Miquel C, Lequette B, Poulle ML, Weber JM, Arlettaz R, Taberlet P (2003) Long-distance wolf recolonization of France and Switzerland inferred from non-invasive genetic sampling over a period of 10 years. Anim Conserv 6:83–92

Vengust G, Valencak Z, Bidovec A (2006) A serological survey of selected pathogens in wild boar in Slovenia. J Vet Med B 53:24–27

Verardi A, Lucchini V, Randi E (2006) Detecting introgressive hybridization between free-ranging domestic dogs and wild wolves (Canis lupus) by admixture linkage disequilibrium analysis. Mol Ecol 15:2845–2855

Zarnke RL, Evermann J, Ver Hoef JM, McNay ME, Boertje RD, Gardner CL, Adams LG, Dale BW, Burch J (2001) Serologic survey for canine coronavirus in wolves from Alaska. J Wildl Dis 37:740–745

Zarnke RL, Ver Hoef JM, DeLong RA (2004) Serologic survey for selected disease agents in wolves (Canis lupus) from Alaska and the Yukon Territory, 1984–2000. J Wildl Dis 40:632–638

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to J. Miklossy for highly valuable comments on this manuscript. We are very appreciative of the detailed and constructive comments provided by the reviewers, which helped to improve the quality of this manuscript. We are very thankful to P. Ciucci for giving access to collected faecal material and to the direction of PNALM for welcomingly facilitating our collaboration. We are also grateful to V. Benetka and K. Walk for the laboratory work and warmly thank V. Benetka for her comments on our results. This study would not have been possible without the help of L. Grottoli, G. Millisher and their collaborators from PNALM and PNM respectively, who collected faecal samples in the field. We also thank K. Kunkel for reviewing the manuscript, as well as S. Rossi and V. Luddeni for discussions regarding the situation in France. This study was funded by the Animal Physiology and Parasitology laboratories, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by C. Gortázar

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Molnar, B., Duchamp, C., Möstl, K. et al. Comparative survey of canine parvovirus, canine distemper virus and canine enteric coronavirus infection in free-ranging wolves of central Italy and south-eastern France. Eur J Wildl Res 60, 613–624 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-014-0825-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-014-0825-0