Abstract

As global temperatures continue to increase and human activities continue to expand, many countries and regions are witnessing the consequences of global climate change. Mongolia, a nomadic and picturesque landlocked country, has battled with ongoing desertification, recurring droughts, and increasingly frequent sandstorms in recent decades. Here we review the abrupt changes in the climate regime of Mongolia over the recent few decades, by focusing on atmospheric events, land degradation and desertification issues, and the resulted sandstorms. We found that between mid-March to mid-April 2021, the country encountered violent gusts of wind, the Mongolia cyclone, and the largest sandstorms in a decade, causing extensive damages nationwide and trans-regional impact in East Asia including northern China, Japan, and most parts of South Korea. A multitude of factors have contributed to this current ecological crisis. Since 1992, the country has transformed to a market economy with high economic growth driven by mineral and agricultural exports. Overgrazing along with intensified human activities such as coal mining has contributed to the widespread land degradation in Mongolia, while climate change has become a major driving factor for recurring droughts. Annual mean air temperature in Mongolia increased by 2.24 °C between 1940 and 2015, while annual precipitation decreased by 7%, resulting in a higher aridity across the country. A positive feedback loop between soil moisture deficits and surface warming has led to a hotter and drier climate in the region, with over a quarter of lakes greater than 1.0-km2 dried up in the Mongolian Plateau between 1987 and 2010. Increased temperatures, decreased precipitation coupled with land degradation have resulted in a persisting drying trend, with more than three-quarters of land in Mongolia being affected by drought and desertification. The 2021 East Asia sandstorms drew international attention to ecological issues that have culminated for decades in Mongolia. Collaborative efforts from policy makers, local residents, and scientists from both its local and the global research community are urgently needed to address the grand and rapidly aggravating ecological challenges in Mongolia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since first put on the agenda as an issue of global concern at the 1st World Climate Conference in Geneva, Switzerland in 1979, climate change and its impact have become more visible in recent decades. Record high temperatures in land and oceans, melting of glaciers at the poles, rising sea levels, and increasingly common weather extremes such as hurricanes, heat waves, wildfires, droughts, and floods have been witnessed at alarming levels (NASA 2020). In early 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) warned that between 2030 and 2050, climate change may lead to approximately 250,000 additional deaths each year due to malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress (WHO 2018). Of these, drought is one of the most widely damaging climate conditions causing or exacerbating water and food security issues (NIDIS 2020). Arid lands already account for over 40% of all land areas of the world today (Nunez 2019). The WHO estimated that, by the end of the twenty-first century, the frequency and intensity of drought may rise to unbearable levels at regional or even global scale under the persisting impact of climate change (WHO 2018). Moreover, climate change has an uneven impact on world’s arid regions in terms of their geographic location, current climate regime, and socioeconomical development, making some countries and regions particularly vulnerable (Abel et al. 2021).

Mongolia, a landlocked country situated between Russia and northern China, is part of the extensive northeastern highland region of the Central Asia Plateau. With an area of 1.56-million km2 and a population of just over three million, it is the eighteenth largest and the most sparsely populated country in the world (WPR 2021). A largely agricultural nation, the country is known for its vast grassland, grazing livestock, picturesque landscape, and nomadic lifestyles (Ankhtuya 2021). Mongolia usually has more than 250 sunny days in a year and is known as the ‘country of eternal blue sky’ (Mongolian: "Mönkh khökh tengeriin oron"). While grassland steppe forms its iconic landscape, arid and semi-arid lands (i.e., annual precipitation < 100 mm) constitute much of its southern and central provinces and stretch from its west to east border (Fig. 1). The Gobi Desert, the second largest rain shadow desert occupying 1.3-million km2 of land, comprises 41.3% of its territory and runs through the southern and southeast regions of Mongolia as well as neighboring provinces in northern China.

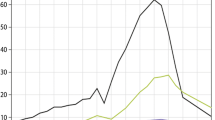

Mongolia has a continental, semi-arid climate with low precipitation and high temperature fluctuations. Nationwide annual precipitation is 227.3 mm based on rainfall records between 1991–2016. About two-thirds of its annual precipitation fall between June and August (WBG 2021), which are unevenly distributed with much lower precipitation in its southern and central desert regions, i.e., 100–200 mm (DeGlopper 1991). Notably, mean annual precipitation in Mongolia decreased from 231.0 mm in 1961–1990 to 222.8 mm between 1991–2016 (WBG 2021) (Fig. 2a). Meanwhile, average monthly temperatures have increased considerably since 1901 (Fig. 2b). Temperatures across Mongolia showed rapid increases between 1982–2015 (Fig. 2c). The highest rate of annual temperature increase was 0.06 °C, and there was no decline in temperature in any region across the country since 1982 (Meng et al. 2020). Summers, when most of the rainfall occurs, have become drier, and extreme climate events have become more common, as commented by G. Purevjav, head of climate research at Mongolia’s Information and Research Institute of Meteorology, Hydrology and Environment (Ankhtuya 2018). Under the impact of global climate change, temperatures in Mongolia are projected to continue rising in future (Fig. 2d).

Trends of average monthly precipitation (a) and temperature (b) in Mongolia. Data are accessed via the Climate Change Knowledge Portal for Development Practitioners and Policy Makers, a database maintained and published by the World Bank Group (WBG, 2021). Spatial distribution of annual mean temperature increases (c) and wind speed variations (e) from 1982 to 2015 are reprinted from Meng et al. (2020). Projected annual mean temperature (2070–2100) is reprinted from Ankhtuya (2018)

In recent decades, the country has battled against intensifying desertification and sandstorms (i.e., dust storms). Official statistics showed that the annual number of days observing sandstorms in Mongolia has increased by more than three-fold since the 1960s (MNETM 2010), causing soil erosion and vegetation deterioration on its already limited arable land. The southern regions of Mongolia consistently witnessed 20 to over 30 sandstorms annually in the past ten years, while drifting dusts are observed on 30–60 days every year in its southern and southwestern regions (NEAC 2021). Most severe sandstorms occur between March and May due to a combination of strong winds and dry soils (Kim 2010). There is also an overall trend of increase in wind speeds in west and east Mongolia with spatial variability across the country (Fig. 2e). The largest increases were found in the northwestern provinces of Mongolia (Khovd, southern Zavkhan, and northern Govi-Altai), where an approximate annual increase of 0.015 m/s was recorded between 1982 and 2015 (Meng et al. 2020).

A dusty spring: ‘Perfect storms’ with trans-regional impact in East Asia

The occurrence of sandstorms depends on both natural climatic variability and human activities (Chen et al. 2020; Guilland et al. 2018; Doichinova et al. 2005), while the intensity of dust emission depends on the wind velocity and soil dryness (Prospero et al. 2002). In spring 2021, violent gusts of wind swept across Mongolia from March 14 to 15, where wind speeds reached 18–34 m/s in Uvurkhangai, Bulgan, and Umnugovi provinces, while in Dundgovi, the wind speed was even higher at 22–40 m/s. Strong winds (16–28 m/s) were also recorded in Govi-Altai, Bayankhongor, Arkhangai, Tuv, Khentii, Dornod, Sukhbaatar, and Dornogovi (OCHA 2021). Under those strong winds, violent sandstorms began to form in the eastern Gobi Desert steppe and subsequently spread to the South Mongolian Plateau, the Loess Plateau, the North China Plain, and the Korean Peninsula. Strong northwest winds, combined with an unusually warm weather (5–8 °C higher than long-term averages) and low precipitation during this spring, as well as the concurrent occurrence of a strong Mongolia cyclone with a central sea level air pressure reaching 980 hPa (WMO 2021), culminated the ideal meteorological conditions for forming vast sandstorms in Mongolia which persisted for two weeks and affected a large part of East Asia (XNA 2021). As of March 16, 2021, the sandstorm affected most of the inland country, causing 10 casualties (9 adults and 1 minor) and 1.6 million livestock missing (Fig. 3). An estimated number of 8,000 people and 2,000 households were affected in 14 provinces across the country in this event.

Adapted from the Situation Report published on March 19, 2021 by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC, 2021)

Yellow areas indicate most affected provinces by severe sandstorms as of March 17, 2021. Images show houses in Dundgovi province facing an arriving sandstorm, a ger (tent) destroyed in Uvs province, livestock killed in Dundgovi province and at an unknown location after the sandstorm. Picture at top left shows the lobe-shaped propagating front of the sandstorm, with dense dust walls up to hundreds of meters high. This event was categorized as ‘catastrophic’ by the Mongolian Government under the Resolution No. 286 (2015).

Mongolian dust storms are one of the main sources of ‘yellow dust’ in East Asia (METM 2018). Airborne debris and particulates in ‘yellow dust’ have severe impact on human activities due to potential respiratory and eye irritations and pathogenic transmission and can cause widespread damages to agriculture, livestock, and animal husbandry (Morman and Plumlee 2014). In Mongolia, over half of the dust storms occur in early spring, with about 60% in March alone, and they are generally less common in summer (7%) or other seasons (METM 2018). Sandstorms are characterized by strong winds with rapid and directional movements (Rodríguez 2007), resulting in trans-regional impact (Fig. 4). On March 15, 2021, the sandstorm spread to Beijing and became the largest one in a decade, according to statistics by China Meteorological Administration (WMO 2021). Visibility was extremely low (< 500 m) and atmospheric coarse particulate matter (PM10) levels peaked at > 9,000 µg/m3 in Beijing (Fig. 4b), while PM10 levels also exceeded 5,000 µg/m3 in Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Ningxia, and northern Hebei (WMO 2021). In less than two weeks, a second sandstorm—also spreading from Mongolia—struck the northern part of China impacting Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Liaoning, and Hebei provinces (TWC 2021a). In the second event, the extremely high level of atmospheric particulates made the sun appear ‘blue’ in the densely hazy sky in Beijing (TWC 2021b), a celestial phenomenon caused by Rayleigh scattering due to high loadings of fine particulates in the atmosphere (Zhou 2021). Over half of the flights were canceled in Inner Mongolia, an Autonomous Region of China boarding with Mongolia and worst hit by the sandstorm. The strong winds carrying dusts and sands continued making their way to the western and northeastern parts of Japan (Fig. 4d) as well as South Korea where authorities issued a ‘yellow dust’ warning for Seoul and most part of the country for the first time in a decade (TWC 2021a). On April 15, 2021, Beijing was hit again by another major sandstorm that spread dense ‘yellow dust’ across its skies and raised atmospheric PM10 levels to nearly twice as the hazardous threshold (Sullivan 2021), which became the third major sandstorm from the Mongolian Plateau that hit the Chinese capital and the northern provinces in just one month.

available at the NASA Earth Observatory (NASA, 2021). The northwest corner tower of the Forbidden City in Beijing, China in the sandstorm on March 15, 2021 (b) and on a clear day (c). Between March 15 and April 15, 2021, the Chinese capital was hit consecutively by three major sandstorms spread from the Mongolian Plateau, with one recognized as the largest one in a decade. Osaka, Japan seen in the sandstorm on March 30, 2021 (d). The trans-regional impact of recent sandstorms was felt in much of the northern China and East Asia. Sources: Xinhua News Agency (XNA, 2021), the Palace Museum (2021), and Japan Today (2021)

Satellite image captured by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite on March 15, 2021 (a). Vast sandstorms spread from Mongolia to neighboring countries including the northern part of China, Japan, and South Korea. High-resolution image is

Driving factors for desertification and sandstorms in Mongolia

Dusts and sandstorms are direct consequences of ongoing desertification which, in turn, is exacerbated by intensified climate change impact and anthropogenic activities (Guo et al. 2019; Cilenti et al. 2005; Kaloudas et al. 2021) (Fig. 5). According to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, approximately 90% of the Mongolian territory is in arid, semi-arid, dry, and sub-humid climatic regions that are susceptible to desertification (Vova et al. 2015). There are many factors that have aided in the desertification process in this region. Of those, a long and irreversible trend of temperature increase, concurrent decrease in annual precipitation, increased evapotranspiration and soil dryness (El-Ramady et al. 2015a, b), as well as widespread land degradation due to overgrazing and human activities are leading factors. Over the past two decades, the magnitude and frequency of weather extremes, most notably droughts and dust storms, have increased by several folds in Mongolia. Extreme and recurring droughts were observed, mostly between june and september, in recent years with both the frequency and severity increased in the past few decades (Fig. 5). In the meantime, meteorological stations throughout Mongolia (n = 34) reported that the number of days observing dust storms each year also increased significantly in recent decades. Dust storms were observed on 18 days in a year in the 1960–1969 period, which increased to 41 days in 1970–1979, 47 days in 1980–1989, 49 days in 1990–1999, and 57 days in 2000–2007, an increase of more than three-fold in four decades (MNETM 2010). While more recent meteorological data are unavailable from the Ministry of Nature, Environment and Tourism of Mongolia, the trend was set to continue with the continuing expansion of the Gobi Desert driven by deforestation and depletion of water resources attributed to human activities as well as climate change (Rossabi 2020).

Adopted from the Third National Communication by the Ministry of Environment and Tourism of Mongolia (METM, 2018). (c) A drought map of Mongolia in the ten-day period starting June 21, 2020. Drought conditions persisted over four months (June 1 to September 30, 2020) in Mongolia with varying degrees of severity across the country. Mongolia as a semi-arid and arid country belongs to a region with high risk of drought. In the five successive years between 2015–2020, drought was widely observed in Mongolia, mostly in summer from June to August. Historical drought maps can be accessed from the National Remote Sensing Center, Information and Research Institute of Meteorology, Hydrology and Environment of Mongolia (NRSC, 2021). Spatial distributions of specific humidity (d) and livestock quantity (e) from 1982 to 2015. Reprinted from Meng et al. (2020). Distribution of total dust events (unit: days) from 2000 to 2017 for severe and moderate sandstorms (f). Reprinted from Zhou et al. (2019)

(a) Land degradation rate in Mongolia reprinted from Kim et al. (2020). According to the empirical models, 76.8% of the land is degraded, of which 22.9% is severely degraded. Assuming that land degradation from desertification is found in arid, semi-arid, dry, and sub-humid areas, the total desertified portion was 64.7%. The method and map of land degradation are developed by the Institute of Geography and Geoecology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences. (b) Interannual change of drought-summer condition index over Mongolia (averaged between May–August). Negative values indicate good summer condition, with positive values indicating drought.

Climate change has been a major driving factor on the local climate in Mongolia. Unprecedented heatwave-drought concurrences have been reported over inner East Asia (i.e., Mongolia and northern China), an area where land-atmospheric coupling has a pronounced role in exacerbating heatwaves and drought. Data recorded at meteorological stations across the country showed that annual mean air temperature increased by 2.24 °C between 1940–2015, and the warmest ten years occurred in the latest decade while annual precipitation decreased by 7% over the past 76 years, resulting in higher aridity across the country (METM 2018). Prior to the recent sandstorms, the country already endured months of reoccurring drought (NRSC 2021). A series of moderate to extreme droughts occurred in its central and southern regions from june through to september 2020, a period when most annual precipitation occurs in the country. Apart from the higher temperatures, low soil moisture, and sparse vegetation also contributed to the severe drought and desertification in some areas. Decreases of specific humidity were evident in central and eastern Mongolia from 1982 to 2015 (Meng et al. 2020), where a negative value of 20 mg kg1 per year was observed in most of these regions (Fig. 5d).

An international group of climate scientists recently securitized heatwave and soil moisture records from local tree ring data and found that the recent consecutive years of record high temperatures and droughts in Mongolia were unprecedented in over 250 years (Zhang et al. 2020). The study also found that record high temperatures in the region are accelerated by soil drying which, in turn, allows direct heat transfers to air due to the lack of moisture kept in soils and subsequent cooling effects induced by evaporation. A positive feedback loop was thus created between soil moisture deficits and surface warming, which causes an abrupt shift to a hotter and drier climate in the region. In an earlier survey, researchers found that more than a quarter of the lakes greater than 1.0-km2 in the Mongolian Plateau had disappeared between 1987–2010 (Tao et al. 2015). Of those, 63 lakes (17.6%) in Mongolia had dried up, including 58 small lakes (1–10 km2), four medium-size lakes (10–50 km2), and one large lake with an area size greater than 50 km2. In a period of just over 20 years, the lake area in Mongolia diminished by 332 km2, representing 2.4% of the total lake area in the inland country. On a longer timescale, the annual reconstruction of the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) spanning over a course of 2060 years showed that recent extreme drought observed on the Mongolian Plateau were highly unusual, which exceeded a 900 year return interval (Hessl et al. 2018). Both the magnitude and pace of those recent changes promoted warnings that the semi-arid region may have entered a new climate regime, in which soil and surface water could no longer mitigate high temperatures and provide adequate precipitation, a failure that can have devastating consequences on the country’s agricultural sector.

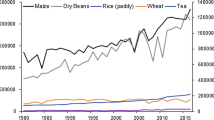

In addition to a drying landscape, overgrazing caused ubiquitous soil and pasture degradation on the vast pasture land, while intensified human activities such as coal mining also contributed to land degradation. Over the past 30 years, grazing intensity has steadily increased across the country (METM 2018). The trend, which started from the early 1990s, accelerated abruptly from 2004, and so was coal mining (from ca. 2000) (Tao et al. 2015). Based on the situation assessment of desertification and land degradation in 2015, more than three-quarters of land (77%) in Mongolia were affected by desertification and land degradation, and nearly a quarter of its land (23%) was considered highly or very highly degraded (METM 2018). Satellite data showed clear evidence that, over a course of 15 years (2001–2015), varying degrees of pasture degradation, i.e., from ‘slight’ to ‘severe’ occurred in most parts of the country due to ubiquitous overgrazing, where the number of livestock exceeded pasture capacity, in addition to the increasing droughts and soil dryness. According to the National Statistical Office of Mongolia, there had been an overwhelming growth in livestock quantity from 24.8–56.0 million between 1982 and 2015, which reached 66.2 million by 2018 (Fig. 5). Studies on changes of livestock heads per unit grazing area found that the number of livestock per 100 hectares of pasture land increased from 40–50 sheep unit (i.e., number of livestock equivalent to sheep heads) between 1980–2000 to 60–70 sheep unit per unit area between 2000–2015. The most abrupt increase was observed from 2010–2015 (METM 2018). The trend was likely to have continued to the present year as indicated by the increasing outputs from the agricultural sector in Mongolia over the last five years (MSIS 2021a).

An ecological imperative

Increased temperatures, coupled with decreased precipitation and ubiquitous land degradation, resulted in a persisting drying trend affecting pastures and water sources in Mongolia, and triggering sustained population shifts to urban regions. Facing drought, desertification, climate change, overgrazing, and mining damage to pasture land, herders who could not make a living continued to migrate to Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia, and lived in gers (tents). In fact, inhabitants of gers (tents) constitute about 60% of the total population in Ulaanbaatar (Rossabi 2020), who are particularly vulnerable to damages by weather extremes such as heatwaves and sandstorms (Fig. 6). In the Third National Communication, the Ministry of Environment and Tourism of Mongolia (METM 2018) estimated that the frequency of disastrous events related to atmospheric phenomena would increase by 23–60% by the middle of this century in any climate change scenario evaluated. In addition, projection data on 2030–2080 painted a dire picture on soil fertility and pasture yield in Mongolia, should the current trends continue without human intervention (METM 2018).

Source: News.mn (Ankhtuya 2019). (b) A ger district on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar. Many of those who now live in the ger district are former herders. Most ger districts are not connected to public water supplies or sanitary systems. Source: Dan Chung of The Guardian (Chung 2021)

(a) Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia, appeared in a sandstorm in April 2019. About 45% of the country’s population live in Ulaanbaatar and surrounding areas. The city experienced recurring and severe sandstorms in recent years.

Neighboring with Mongolia, China has endured and battled with desertification and sandstorms for decades in its northern provinces (Feng et al. 2015; Yu et al. 2014; Gu et al. 2021). Due to its proximity to the Gobi Desert, Beijing—as other cities situated in the Mongolian Plateau—has a sandy past with recurring ‘yellow dust’ in spring. Yet, those vast, sky-darkening sandstorms seen between March 15 and April 15 this year may have become remote memories for its residents. Since the late 1970s, the Chinese government invested tremendous resources in the ‘Three-North Shelter Forest Program’ to reverse desertification and mitigate sandstorms by planting aspens and other fast-growing trees on approximately 36.5 million hectares of land in 12 northern provinces. Efforts further accelerated in its northern and northwestern regions since the early 2000s to mitigate desertification and remediate land degradation to block winds and to fixate sands and soils by reforestation. The average number of sandy days fell sharply in Beijing, from 25 in the 1950s to three in 2010, and sandstorms became rare in the past ten years.

As one of the countries that are most severely impacted by climate change and desertification, Mongolia is a developing nation with a vast land territory and a small population with a modest human development index (Fig. 7). Yet, its governments and residents are facing a daunting and rapidly aggravating ecological challenge. Ecological remediation of this scale requires vast resources, expertise, and decades of persisting efforts (Fawzy et al. 2020). The 2021 East Asia sandstorm has drawn international attention to ecological issues that have been culminating for decades in Mongolia. Addressing these issues would require decades of collaborative efforts from climate, ecological, atmospheric, and environmental scientists from the local and global research communities. In the renowned Mongolian folk song ‘The Night of Ulaanbaatar’, the songwriter painted the tranquility of life and picturesque landscape in Ulaanbaatar. It is now a matter of actions for its regulators, scientists, and residents to regain such lifestyles in the ‘country of eternal blue sky’.

Economy and population growth of Mongolia between 1970–2020. Nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) data between 2010–2020 are from the National Statistics Office of Mongolia (MSIS) and the World Bank (2021a). Data from MSIS and the World Bank are consistent on overlapping years (2010–2020). Population data are from the World Bank (2021b). Since 1992, Mongolia has transformed to a market economy seeking to expand its trade and export. The country has seen sustained growth with increasing population and economy outputs. Trading with China, currently the largest trading partner of Mongolia, grew substantially from 1.3 billion in 2005–1 billion U.S. dollars in 2020 (MSIS 2021b), largely driven by exports of agricultural and mining products. The lockdown caused by the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) resulted in a negative GDP growth (− 5.3%) in 2020 (MSIS 2021c). At the time of writing (24 June 2021), the country reported 98,050 confirmed cases of COVID-19 infections with 459 deaths (WHO 2021). Despite the COVID-19 impact, China continued to be Mongolia’s largest trading partner and the largest export market for its mineral and natural resources (MSIS 2021b). With a life expectancy of 69.9 years and a gross national income per capital of $10,840, the country was ranked the 99th of 189 countries on the Human Development Index by the United Nations in 2020, an improvement from the 117th in 2000 (UNDP 2020)

Conclusion

The 2021 East Asia sandstorms drew international attention to ecological issues that have culminated for decades in Mongolia, a landlocked country with vast arid and semi-arid land that is highly vulnerable to climate change. In the past few decades, the country has battled with severe, recurring droughts and vast, increasingly frequent sandstorms. Recognizing the key driving factors is of great importance for fighting against the ongoing desertification and dust storms in the Mongolia Plateau. By securitizing long-term climate data, we found persisting trends of temperature rise and precipitation decrease in Mongolia. Meanwhile, intensifying overgrazing and human activities caused rapid and abrupt increases of land degradation in some regions. Climate factors and land degradation have resulted in a positive feedback loop between soil moisture deficits and surface warming in the region, yielding a hotter, and drier climate regime with unprecedented drought witnessed in recent years. There is, however, major knowledge gaps that most existing data and models failed to take the spatial heterogeneity of variables into account, which is highly relevant given the vast land territory and sparse distribution of population in Mongolia. Since overgrazing and human activities are primary driving factors of land degradation in many regions, there is also a need to devise more accurate, area-specific models to identify the key driving factors and to implement mitigation strategies. Governments and residents in Mongolia are facing a daunting and rapidly aggravating ecological crisis which requires tremendous resources and expertise to remediate in the next few decades. Ecological restoration on such a vast scale requires persisting and collaborative efforts from scientists around the world, in which environmental and atmospheric scientists have a pivotal role to take in tackling this grand ecological challenge.

References

Abel C, Horion S, Tagesson T, Keersmaecker WD, Seddon AWR, Abdi AM, Fensholt R (2021) The human–environment nexus and vegetation–rainfall sensitivity in tropical drylands. Nat Sustain 4:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00597-z

Ankhtuya (2018) Mongolia calls for global attention on climate change. News.mn https://news.mn/en/785460/. Accessed 25 June 2021

Ankhtuya (2019) Mongolian nomadic life captured in photos. https://news.mn/en/795243/. Accessed 25 June 2021

Ankhtuya (2021) Dust storm covers Ulaanbaatar. https://news.mn/en/787344/. Accessed 25 June 2021

Beck HE, Zimmermann NE, McVicar TR, Vergopolan N, Wood EF (2018) Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci Data. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.214

Chen FH, Chen SQ, Zhang X, Chen JH, Wang X, Gowan EJ, Qiang MG, Dong GH, Wang ZL, Li YC, Xu QH, Xu YY, Smol JP, Liu JB (2020) Asian dust-storm activity dominated by Chinese dynasty changes since 2000 BP. Nat. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14765-4

Chung D (2021) Life in Ulaanbaatar's tent city is hard – but Mongolians won't give up their gers. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/sep/03/mongolia-ulanbaatar-ger-yurt-tent-city. Accessed 25 June 2021

Cilenti A, Provenzano MR, Senesi N (2005) Characterization of dissolved organic matter from saline soils by fluorescence spectroscopy. Environ Chem Lett 3:53–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-005-0001-6

DeGlopper DR (1991) The Society and Its Environment. In: Worden RL, Savada AM (eds) Mongolia: a country study. Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/resource/frdcstdy.mongoliacountrys00word_0/?sp=3&st=gallery. Accessed 25 June 2021

Doichinova V, Zhiyanski M, Hursthouse A (2005) Impact of urbanisation on soil characteristics. Environ Chem Lett 3:160–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-005-0024-z

El-Ramady HR, Abdalla N, Alshaal T, Elhenawy AS, Shams MS, Faizy S, Belal ESB, Shehata SA, Ragab MI, Amer MM, Fari M, Sztrik A, Prokisch J, Selmar D, Schnug E, Pilon-Smits EAH, El-Marsafawy SM, Domokos-Szabolcsy E (2015a) Giant reed for selenium phytoremediation under changing climate. Environ Chem Lett 13(4):359–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-015-0523-5

El-Ramady HR, AbdallaDomokos-Szabolcsy NÉ, ElhawatProkischSztrikFáriEl-Marsafawy Shams NJAMSMS (2015b) Selenium in soils under climate change, implication for human health. Environ Chem Lett 13:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-014-0480-4

Fawzy S, Osman AI, Doran J, Rooney DW (2020) Strategies for mitigation of climate change: a review. Environ Chem Lett 18:2069–2094. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-020-01059-w

Feng Q, Ma H, Jiang XM, Wang X, Cao SX (2015) What Has Caused Desertification in China? Sci Rep 5:15998. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15998

GloH2O (2021) Köppen-Geiger Global 1‑km climate classification maps. http://www.gloh2o.org/koppen/. Accessed 25 June 2021

Gu Z, He Y, Zhang Y, Su J, Zhang R, Yu CW, Zhang D (2021) An overview of triggering mechanisms and characteristics of local strong sandstorms in China and haboobs. Atmosphere 12:752. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos12060752

Guilland C, Maron PA, Damas O, Ranjard L (2018) Biodiversity of urban soils for sustainable cities. Environ Chem Lett 16:1267–1282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-018-0751-6

Guo P, Yu SC, Wang LQ, Li PF, Li Z, Mehmood K, Chen X, Liu WP, Zhu YN, Yu X, Alapaty K, Lichtfouse E, Rosenfeld D, Seinfeld JH (2019) High-altitude and long-range transport of aerosols causing regional severe haze during extreme dust storms explains why afforestation does not prevent storms. Environ Chem Lett 17:1333–1340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-019-00858-0

Hessl AE, Anchukaitis KJ, Jelsema C, Cook B, Byambasuren O, Leland C, Nachin B, Pederson N, Tian HQ, Hayles LA (2018) Past and future drought in Mongolia. Sci Adv 4:e1701832. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1701832

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) (2021) Emergency Plan of Action, Mongolia: Sandstorm. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/MDRMN014do.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2021

Kaloudas D, Pavlova N, Penchovsky R (2021) Lignocellulose, algal biomass, biofuels and biohydrogen: a review. Environ Chem Lett. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-021-01213-y

Kim HS, Chung YS (2010) On the sandstorms and associated airborne dustfall episodes observed at Cheongwon on Korea in 2005. Air Qual Atmos Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11869-009-0054-y

Kim J, Dorjsuren M, Choi Y, Purevjav G (2020) Reconstructed Aeolian Surface Erosion in Southern Mongolia by Multi-Temporal InSAR Phase Coherence Analyses. Front Earth Sci 8:531104. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2020.531104

Meng XY, Gao X, Li SY, Lei JQ (2020) Spatial and Temporal Characteristics of Vegetation NDVI Changes and the Driving Forces in Mongolia during 1982–2015. Remote Sens 12(603):1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12040603

Ministry of Environment and Tourism of Mongolia (METM) (2018) Third National Communication of Mongolia, under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/06593841_Mongolia-NC3-2-Mongolia%20TNC%202018%20pr.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2021

Ministry of Nature, Environment and Tourism of Mongolia (MNETM) (2010) Mongolia Second National Communication, under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/mongnc2.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2021

Mongolian Statistical Information Service (MSIS) (2021a) Industry statistics. https://www.1212.mn/stat.aspx?LIST_ID=976_L11&year=2020&month=12. Accessed 25 June 2021

Mongolian Statistical Information Service (MSIS) (2021b) Foreign trade statistics. https://www.1212.mn/Stat.aspx?LIST_ID=976_L14. Accessed 25 June 2021

Mongolian Statistical Information Service (MSIS) (2021c) National accounts statistics. http://1212.mn/stat.aspx?LIST_ID=976_L05. Accessed 25 June 2021

Morman SA, Plumlee GS (2014) Dust and Human Health. Min Dust 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8978-3_15

NASA (2020) Global climate change: overview: weather, global warming and climate change. https://climate.nasa.gov/resources/global-warming-vs-climate-change/. Accessed 25 June 2021

NASA (2021) Earth observatory. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/148052/early-season-dust-storm-hits-beijing. Accessed 25 June 2021

National Remote Sensing Center (NRSC) (2021) Information and Research Institute of Meteorology, Hydrology and Environment, Remote sensing product, MODIS product-drought. http://icc.mn/index.php?menuitem=5&datatype=mdro. Accessed 25 June 2021

Northeast Asian Conference on Environmental Cooperation (NEAC), Dust storms in Mongolia. https://www.env.go.jp/earth/coop/neac/neac12/pdf/021.pdf. Accessed 25 June 2021

Nunez Christina (2019) Desertification, explained. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/desertification. Accessed 25 June 2021

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) of the United Nations (2021) Mongolia: Sandstorm-Mar 2021. https://reliefweb.int/disaster/st-2021-000024-mng. Accessed 25 June 2021

Prospero JM, Ginoux P, Torres O, Nicholson SE, Gill TE (2002) Environmental characterization of global sources of atmospheric soil dust identified with the NIMBUS 7 Total ozone mapping spectrometer (TOMS) absorbing aerosol product. Rev Geophys 40:1–31. https://doi.org/10.1029/2000RG000095

Rodríguez S, Querol X, Alastuey A, Rosa J (2007) Atmospheric particulate matter and air quality in the Mediterranean: a review. Environ Chem Lett 5:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-006-0071-0

Rossabi M (2021) Mongolia in 2020: Less COVID, Lots of problems. Asian Surv 61:43–48. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2021.61.1.43

Sullivan H (2021) Beijing hit by third sandstorm in five weeks. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/16/beijing-hit-by-third-sandstorm-in-just-over-a-month. Accessed 25 June 2021

National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS), Global Drought Condition. https://www.drought.gov/international. Accessed 25 June 2021

Tao SL, Fang JY, Zhao X, Zhao SQ, Shen HH, Hu HF, Tang ZY, Wang ZH, Guo QH (2015) Rapid loss of lakes on the Mongolian Plateau. P Natl Acad Sci USA 112:2281–2286. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1411748112

The Palace Museum. https://www.dpm.org.cn/explore/building/236522.html. Accessed 25 June 2021

The Weather Channel (TWC) (2021a) Mongolia's Dust Storm Spreads to China, Japan and South Korea. https://weather.com/photos/news/2021-03-30-sandstorm-photos. Accessed 25 June 2021

The Weather Channel (TWC) (2021b) Sun Turns Blue in Beijing Dust Storm. https://weather.com/news/weather/video/sun-turns-blue-in-beijing-dust-storm. Accessed 25 June 2021

Japan Today (JT) (2021) Yellow sandstorm blankets part of western Japan. https://japantoday.com/category/national/yellow-sandstorm-blankets-part-of-western-japan. Accessed 25 June 2021

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2020) Human Development Reports 1990–2020, The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene. http://hdr.undp.org/en/global-reports. Accessed 25 June 2021

Vova O, Kappas M, Renchin T and Degener J (2015) Land Degradation Assessment in Gobi-Altai Province. Proceedings of the Trans-disciplinary Research Conference: Building Resilience of Mongolian Rangelands, Ulaanbaatar Mongolia, June 9–10, 2015. https://warnercnr.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/09/2015BuildingResilience_of_MongolianRangelands-ENG1-6Vova_etal.pdf

World Bank (2021a) World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CN?end=2019&locations=MN&start=1981&view=chart. Accessed 25 June 2021

World Bank (2021b) World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=MN. Accessed 25 June 2021

World Bank Group (WBG) (2021) Climate Change Knowledge Portal, for Development Practitioners and Policy Makers. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/mongolia/climate-data-historical. Accessed 25 June 2021

World Health Organization (WHO) (2018) Climate change and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health#:~:text=Between%202030%20and%202050%2C%20climate%20change%20is%20expected,year%2C%20from%20malnutrition%2C%20malaria%2C%20diarrhoea%20and%20heat%20stress. Accessed 25 June 2021

World Health Organization (WHO) (2021) Mongolia Situation. https://covid19.who.int/region/wpro/country/mn. Accessed 25 June 2021

World Meteorological Organization (WMO) (2021) Severe sand and dust storm hits Asia. https://public.wmo.int/en/media/news/severe-sand-and-dust-storm-hits-asia. Accessed 25 June 2021

World Population Review (WPR) (2021) Mongolia Population 2021 (Live). https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/mongolia-population. Accessed 25 June 2021

Xinhua News Agency (XNA) (2021) Satellite imagery shows the severity of sandstorms from Mongolia. http://www.xinhuanet.com/multimediapro/2021-03/15/c_1211067217.htm (in Chinese). Accessed 25 June 2021

Yu SC, Zhang QY, Yan RC, Wang S, Li PF, Chen BX, Liu WP, Zhang XY (2014) Origin of air pollution during a weekly heavy haze episode in Hangzhou, China. Environ Chem Lett 12:543–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-014-0483-1

Zhang P, Jeong JH, Yoon JH, Kim H, Wang SYS, Linderholm HW, Fang KY, Wu XC, Chen DL (2020) Abrupt shift to hotter and drier climate over inner East Asia beyond the tipping point. Science 370:1095–1099. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb3368

Zhou X (2021) China pollution: Beijing sandstorm turns sky to yellow and sun to blue. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3127317/china-pollution-beijing-sandstorm-turns-sky-yellow-and-sun-blue. Accessed 25 June 2021

Zhou C, Gui H, Hu J, Ke H, Wang Y, Zhang X (2019) Detection of new dust sources in central/East Asia and their impact on simulations of a severe sand and dust storm. J Geophys Res: Atmos 124(10):232–247. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD030753

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Young Talent Support Plan of Xi’an Jiaotong University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Han, J., Dai, H. & Gu, Z. Sandstorms and desertification in Mongolia, an example of future climate events: a review. Environ Chem Lett 19, 4063–4073 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-021-01285-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-021-01285-w