Abstract

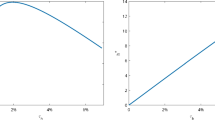

This paper explores in a two-period model the economic implications of people’s tendency to underestimate their ability to adapt to age-related health problems. We model this misperception by assuming that the individual underestimates his future subjective health. Under standard assumptions, we show that, when people allocate their resources during their youth between present consumption, savings, and health investment, they invest more in health as long as the magnitude of the cross-marginal utility of health and consumption is not too negative.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

After ruling out the possibility of a pure cohort effect and controlling for income, Blanchflower and Oswald [22] found a U-curve of happiness through the life cycle for Americans and Europeans. After controlling for more factors such as marital status, children, and work status, and once again excluding simple cohort effect, Yang [23] found an increasing path this time for Americans.

This assumption fits well with the observation that the subjectively perceived age does not increase as fast as the biological age when people get older [43].

As one anonymous reviewer noticed, our modeling of hedonic adaptation could also be interpreted in terms of a state-dependent utility function v t = v(c t , h t , s t ) in which the state in t (s t ) depends on the change in health (h 0 − h t ) and on an exogenous parameter α that measures the degree to which the initial level of health affects present utility. In our model, s 0 = 0 and s 1 = α(h 0 − h 1) so that v 0 = v(c 0, h 0, 0) and v 1 = v(c 1, h 1, α(h 1 – h 0)). Furthermore, we give an exact specification to this state dependence by assuming that v(c 0, h 0, 0) = u(c 0, h 0) and v(c 1, h 1, α(h 1 − h 0)) = u(c 1, h 1 + α(h 1 − h 0)).

We take some liberty with notations here. Strictly speaking, we should write that \( \partial u(c_{1} ,h_{1}^{\alpha } (h_{1} ))/\partial h_{1} < \partial u(c_{1} ,h_{1} )/\partial h_{1} \) with \( h_{1}^{\alpha } (h_{1} ) = h_{1} + \alpha (h_{0} - h_{1} ) \). An important aspect of our modeling is that in the presence of hedonic adaptation, second-period utility depends on c 1 and indirectly on objective health h 1 through equation (1). The utility function at the second period in the presence of hedonic adaptation can thus be expressed either directly as a function of c 1 and \( h_{1}^{\alpha } \), that is \( u(c_{1} ,h_{1}^{\alpha } ) \), or as a composite function \( u(c_{1} ,h_{1}^{\alpha } (h_{1} )) \) with c 1 and h 1 as arguments.

Note here a potential confusion about the meaning of the marginal utility of h 1. By definition, it represents the marginal utility of h for h = h 1 with h 1 < h 0. Since ∆(h 1 – h 0) = ∆h 1 for h 0 given, we could say equivalently that it represents the extra utility provided by a marginal moderation of health deterioration. This is our preferred interpretation for the understanding of the model developed in the rest of the paper. In a two-period model, decisions are taken only once at the first period (t 0 ). Health capital no longer changes once it has reached its value in t 1 . It could thus be potentially confusing to think about the marginal utility of h 1 as representing the extra utility provided by a marginal change of health in t 1 .

Frederick and Loewenstein [3] illustrate this mechanism with an apt example of a prisoner who has been incarcerated. As long as the prisoner considers freedom as his reference point, the difference in value between a small cell and a large cell is perceived as insignificant. However, if the prisoner anticipates his adaptation to incarceration by taking a lower reference point (incarceration in a small cell, for instance), then the difference in value between those two cells will be given a larger value.

Note that this mechanism is less likely to come into play when we exclude such adverse conditions or when the individual can significantly limit health deterioration. For instance, if the individual has access to treatments that not only prolong his life but also greatly improve his health condition, these treatments will surely be highly desirable even for individuals in good health and prior to any anticipation of hedonic adaptation to health deterioration.

In practice, a large part of health practices also affect present health, in particular if health is understood in a broad sense as also including the aesthetic capital. But since we are only concerned with efforts which create marginal long-term health benefits (even low), the individual still has to make a trade-off between present and future satisfaction. We can simplify the analysis by assuming that the benefits of health are only observed at the second period.

We would get exactly the same qualitative results by considering that saving is simply constant, positive or negative but not necessarily equal to 0. This assumption also implies that health has no wealth effect.

This is consistent with conclusions reached by other models of hedonic adaptation in the literature. For instance, the model of Carbone et al. [41] predicts that a person who adapts psychologically to poorer health will smoke more during his earlier life and will shift the demand for health investments with a net increase in smoking over the life cycle. Using a simple dynamical Grossman model of health investment, Gjerde et al. [40] also found that adaptation lowers the incentives to invest in health, as well as smoothing the optimal health stock path over the life cycle.

References

Palmore, E.B.: Three decades of research on Ageism. Generations 24(3), 87–90 (2005)

Cutler, N.E., Whitelaw, N.W., Beattie, B.L.: American Perceptions of Aging in the 21st Century. The NCOA’s Continuing Study of the Myths and Reality of Aging. National Council on the Aging, Washington, DC (2002)

Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G.: Hedonic adaptation. In: Kahneman, D., Diener, E., Schwartz, N. (eds.). Scientific Perspectives on Enjoyment, Suffering, and Well-Being. Russell Sage Foundation, New York (1999)

Ashby, J., O’Hanlon, M., Buxton, M.J.: The time trade-off technique: how do the valuations of breast cancer patients compare to those of other groups? Qual. Life Res. 3, 257–265 (1994)

Wu, S.: Adapting to heart conditions: a test of the hedonic treadmill. J. Health Econ. 20, 495–508 (2001)

Riis, J., Loewenstein, G., Baron, J., Jepson, C., Fagerlin, A., Ubel, P.: Ignorance of hedonic adaptation to hemodialysis: a study using ecological momentary assessment. J. Exp. Psychol. 134(1), 3–9 (2005)

Brickman, P., Coates, D., Janoff-Bulman, R.: Lottery winners and accident victims: is happiness relative? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 36(8), 917–927 (1978)

Albrecht, G.L., Devlieger, P.J.: The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Soc. Sci. Med. 48, 977–988 (1999)

Pagan-Rodriguez, R.: Onset of disability and life satisfaction: evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel. Eur. J. Health. Econ. 11(5), 471–485 (2010)

Sackett, D.L., Torrance, G.W.: The utility of different health states as perceived by the general public. J. Chronic Dis. 31, 697–704 (1978)

Boyd, N., Sutherland, H.J., Heasman, K.Z., Tritcher, D.L., Cummings, B.: Whose utilities for decision analysis? Med. Decis. Mak. 10, 58–67 (1990)

Hurst, N.P., Jobanputra, P., Hunter, M., Lambert, M., Lockhead, A., Brown, H.: Validity of EuroQolF: A generic health status instrument for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Rheumatol. 33, 655–662 (1994)

Buick, D.L., Petrie, K.J.: “I know just how you feel”: The validity of healthy women’s perceptions of breast cancer patients receiving treatment. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32, 110–123 (2002)

Baron, J., Asch, D.A., Fagerlin, A., Jepson, C., Loewenstein, G., Riis, J., et al.: Effect of assessment method on the discrepancy between judgments of health disorders people have and do not have: A web study. Med. Decis. Mak. 23, 422–434 (2003)

Pyne, J.M., Fortney, J., Tripathi, S., Feeny, D., Ubel, P.A., Brazier, J.: How bad is depression? Preference score estimates from depressed patients and the general population. Health Serv. Res. 44, 1406–1423 (2009)

Lacey, H.P., Fagerlin, A., Loewenstein, G., Smith, D.M., Riis, J., Ubel, P.A.: Are they really that happy? Exploring scale recalibration in estimates of well-being. Health Psychol. 27(6), 669–675 (2008)

Slevin, M.L., Stubbs, L., Plant, H.J., Wilson, P., Gregory, W.M., Armes, P.J., et al: Attitudes to chemotherapy: comparing views of patients with cancer with those of doctors, nurses, and general public. Br. Med. J. 300(6737):1458–1460 (1990)

Ubel, P., Loewenstein, G., Schwarz, N., Smith, D.: Misimagining the unimaginable: the happiness gap and healthcare decision making. Health Psychol. 24(4), S57–S62 (2005)

Ubel, P.A., Loewenstein, G., Hershey, J., et al.: Do nonpatients underestimate the quality of life associated with chronic health conditions because of a focusing illusion? Med. Dec. Mak. 21(3), 190–199 (2001)

Damschroder, L.J., Zikmund-Fisher, B.J., Ubel, P.A.: The impact of considering adaptation in health state valuation. Soc. Sci. Med. 61(2), 267–277 (2005)

Gilbert Daniel, T., Pinel, E.C., Wilson, T.D., Blumberg, S.J., Wheatley, T.P.: Immune neglect: a source of durability bias in affective forecasting. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 75, 617–638 (1998)

Blanchflower, D.G., Oswald Andrew, J.: Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Soc. Sci. Med. 66(8), 1733–1749 (2006)

Yang, Y.: Social inequalities in happiness in the United States, 1972 to 2004: an age-period cohort analysis. Am. Sociol. Rev. 73, 204–226 (2008)

Lacey, H., Smith, D., Ubel, P.: Hope I die before I get old: mispredicting happiness across the adult lifespan. J. Happiness Stud. 7(2), 167–182 (2006)

Bryce, C.L., Loewenstein, G., Arnold, R.M., Schooler, J., Wax, R.S., Angus, D.C.: Quality of death and dying: assessing the importance people place on different domains of end-of-life care. Med. Care 42(5), 423–431 (2004)

Knapp, J.L., Stubblefield, P.: Changing students’ perceptions of aging: the impact of an intergenerational service learning course. Educ. Gerontolog. 26, 611–621 (2000)

Van Maanen, H.M.T.: Being old does not always mean being sick: Perspectives on conditions of health as perceived by British and American elderly. J. Adv. Nur. 13, 701–709 (1988)

Charles, S., Mather, M., Carstensen, L.: Aging and emotional memory: the forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. J. Exp. Psychol. 132(2), 310–324 (2003)

Fung, H., Carstensen, L.: Sending memorable messages to the old: age differences in preferences and memory for advertisements. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 85(1), 163–178 (2003)

Carstensen, L., Pasupathi, M., Mayr, U., Nesselroade, J.: Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 79, 644–655 (2000)

Ross, C., Mirowsky, J.: Age and the balance of emotions. Soc. Sci. Med. 66(12), 2391–2400 (2008)

Carstensen, L., Isaacowitz, D., Charles, S.: Taking time seriously: a theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 54, 165–181 (1999)

Loewenstein, G., O’Donoghue, T., Rabin, M.: Projection bias in predicting future utility. Q. J. Econ. 118(4), 1209–1248 (2003)

Fried, T.R., Byers, A.L., Gallo, W.T., Van Ness, P.H., Towle, V.R., O’Leary, J.R., et al.: Prospective study of health status preferences and changes over time in older adults. Arch. Intern. Medicine. 166, 890–895 (2006)

Tsevat, J., Dawon, N.B., Wu, A.W., Lynn, J., Soukup, J.R., Cook, E.F., et al.: Health values of hospitalized patients 80 years or older. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 279, 371–375 (1998)

O’Brien, L., Grisso, J.A., Maislin, G., LaPann, K., Krotki, K.P., Greco, P.J., et al.: Nursing home residents’ preferences for life-sustaining treatments. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 274, 1775–1779 (1995)

Winter, L., Parker, B.: Current Health and preferences for life-prolonging treatments: an application of prospect theory to end-of-life decision making. Soc. Sc. Med. 65, 1695–1707 (2007)

Kahneman, D., Tversky, A.: Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47, 263–291 (1979)

Macé, S., Le Lec, F.: On fatalist long-term health behavior. J. Eco. Psychol. 32(3), 434–439 (2011)

Gjerde, J., Grepperudb, S., Kverndokk, S.: On adaptation and the demand for health. Appl. Econ. 37, 1283–1301 (2005)

Carbone, J.C., Kverndokk, S., Rogeberg, O.J.: Smoking, health, risk and perception. J. Health Econ. 24, 631–653 (2005)

Groot, W.: Adaptation and scale of reference bias in self-assessments of quality of life. J. Health Econ. 19, 403–420 (2000)

Demakakos, P., Hacker, E., Gjonça, E.: Perceptions of aging in: retirement, health and relationships of the older population in England. In: Banks, J., Breeze, E., Carli, L., Nazroo, J. (eds.) The 2004 English longitudinal study of ageing (wave 2). The Institute for Fiscal Studies, London (2006)

Brickman, P., Campbell, D.T.: Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In: Appley, M.H. (ed.) Adaptation Level Theory: A Symposium, pp. 287–302. Academic, New York (1971)

Diener, E., Lucas, R.E., Scollon, C.N.: Beyond the hedonic treadmill. Am. Psychol. 61(4), 305–314 (2006)

Carroll, C.D., Overland, J., Weil, D.N.: Saving and growth with habit formation. Am. Econ. Rev. 90, 341–355 (2000)

Janz, N.K., Champion, V.L., Strecher, V.J.: The health belief model. In: Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Lewis, F.M. (eds.) Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice 3rd edn, pp. 45–66. Jossey-Bass. San Francisco, CA (2008)

Brewer, N.T., Chapman, G.B., Gibbons, F.X., Gerrard, M., McCaul, K.D., Weinstein, N.D.: Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychol. 26, 136–145 (2007)

Prentice-Dunn, S., Mcmath, B., Cramer, R.: Protection motivation theory and stages of change in sun protective behavior. J. Health Psychol. 14, 297–305 (2009)

Ebner, N.C., Freund, A.M., Baltes, P.B.: Developmental changes in personal goal orientation from young to late adulthood: from striving for gains to maintenance and prevention of losses. Psychol. Aging 21(4), 664–678 (2006)

Slevec, J., Tiggerman, M.: Attitudes toward cosmetic surgery in middle-aged women: body image, aging anxiety, and the media. Psychol. Wom. Q. 34(1), 65–74 (2010)

Finkelstein, A., Luttmer, E., Notowidigdo, M.: Approaches to estimating the health state dependence of the utility function. Am. Econ. Rev. 99(2), 116–121 (2009)

Sloan, F., Viscusi, K., Chesson, H., Conover, C., Whetten-Goldstein, K.: Alternative approaches to valuing intangible health losses: the evidence for multiple sclerosis. J. Health Econ. 17(4), 475–497 (1998)

Viscusi, K., Evans, W.: Utility functions that depend on health status: estimates and economic implications. Am. Econ. Rev. 80(3), 353–374 (1990)

Evans, W., Viscusi, K.: Estimation of state dependent utility functions using survey data. Rev. Econ. Stat. 73(1), 94–104 (1991)

Finkelstein, A., Luttmer, E., Notowidigdo, M.: What good is wealth without health? The effect of health on the marginal utility of consumption. NBER Work. Pap. 14089 (2008)

Lillard, L., Weiss, Y.: Uncertain health and survival: effects of end-of-life consumption. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 15(2), 254–268 (1997)

Edwards, R.: Health risk and portfolio choice. J. Busin. Econ. Stat. 26(4), 472–485 (2008)

Walsh, E.: What would it be like for me and for you? Judged impact of chronic health conditions on happiness. Med. Decis. Making 29, 15–22 (2009)

Kősegi, B., Rabin, M.: A model of reference-dependant preferences. Q. J. Econ. 121, 1133–1265 (2006)

Acknowledgments

We thank Louis Eeckhoudt and David Crainich for helpful comments on preliminary versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Comparative statics of the general model: proof of propositions 2

Appendix: Comparative statics of the general model: proof of propositions 2

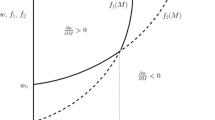

The individual’s optimization program in 3.2 is given by:

In order to use standard shortcuts notations for derivatives, the discounted utility function of the second period is written v(c, h) instead of δu(c, h). The two (sufficient) first-order conditions are given by:

The second partial derivatives of \( \hat{U}(c^{*} ,i^{*} ) \) are:

The differentiation of the two first-order conditions with respect to i,c and m forms a system of two equations:

Cramer’s rule implies:

Since the determinant of J is positive, the sign of di */dm is given by the sign of A. To compute A, remember first that \( \hat{h}_{1}^{\prime } (i^{*} ) = (1 - \alpha + \alpha m)h_{1}^{\prime } (i^{*} ) \)and note that:

Using new shortcuts notations, h 1 = h 1(i*) and \( \hat{h}_{1} = \hat{h}_{1} (i^{*} ) \), replacing these values in B gives:

So

It also follows straightforwardly from Eq. (29) that if v ch is strongly negative, it is possible that A > 0 and di*/dm < 0. For some values or m, the individual may now underinvest in health.

Further comments: Cramer’s rule also allows computation of the effect of a change in m on c* and s*. In particular, we have:

which makes it possible to write \( \frac{{{\text{d}}(s^{*} + i^{*} )}}{{{\text{d}}m}} = - \frac{{{\text{d}}c^{*} }}{{{\text{d}}m}} \) and so

s* + i* is the amount of present resources that the individual chooses to allocate to the future, either to health or consumption. B is equal to \( {{ - \partial \hat{U}_{c} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{ - \partial \hat{U}_{c} } {\partial m}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial m}} \cdot \hat{U}_{ii} + {{\partial \hat{U}_{i} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial \hat{U}_{i} } {\partial m}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial m}} \cdot \hat{U}_{ic} \) or after replacing by:

If we develop then simplify, we get:

Therefore, as long as v ch is not too strongly negative, the individual over invests in health; but without more restrictions on the utility function, we cannot be sure of the net effect of m on the amount of resources allocated to the future for health and consumption.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jokung, O., Macé, S. Long-term health investment when people underestimate their adaptation to old age-related health problems. Eur J Health Econ 14, 1003–1013 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-012-0449-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-012-0449-9