Abstract

Cauda equina paragangliomas are rare benign extra-adrenal neuroendocrine tumours arising from the neural crest cells associated with autonomic ganglia. These tumours are often mistaken preoperatively for ependymomas or schwannomas. Patients present with axial or radicular pain with or without neurological deficits. Recurrence, secretory features and length of follow-up are controversial. We conducted a retrospective cohort study of paraganglioma through searching a prospectively maintained histopathology database. Patient demographics, presentation, surgery, complications, recurrence, follow-up and outcome between 2004 and 2016 were studied. The primary aim was to collate and describe the current evidence base for recurrence and secretory features of the tumour. The secondary objective was to report outcome and follow-up strategy. A scoping review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR Checklist. Ten patients were diagnosed (M:F 7:3) with a mean age of 53.6 ± 5.1 (range 34–71 years). MRI scans revealed intradural lumbar enhancing lesions. All patients had complete microsurgical excisions without adjuvant therapy with no recurrence with a mean follow-up of 5.1 ± 1.4 years. Tumours were attached to the filum terminale. Electron microscopic images demonstrated abundant neurosecretory granules with no evidence of catecholamine production. A total of 620 articles were screened and 65 papers (including ours) combining 121 patients (mean age 48.8 and M:F 71:50) were included. The mean follow-up was 3.48 ± 0.46 (range 0.15–23 years). Back pain was the most common symptom (94%). Cure following surgery was achieved in 93% of the patients whilst 7% had recurrence. Total resection likely results in cure without the need for adjuvant therapy or prolonged follow-up. However, in certain situations, the length of follow-up should be determined by the treating surgeon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Paraganglioma is a rare neuroendocrine extra-adrenal tumour histologically similar to pheochromocytoma but is distinguished by anatomical location [46]. They arise from neural crest-derived cells or paraganglia and may be either sympathetic (secreting catecholamines) or parasympathetic non-secretory lesions [46]. Histologically, they are slow growing with a benign appearance and have been classified as World Health Organization (WHO) grade I tumours [46]. In the central nervous system, the vast majority are located in the jugular glomus, as well as the carotid bodies which are the most common extra-adrenal site [64]. Paragangliomas of the spine as primary tumours are extremely rare with just over 200 cases reported in the English literature so far [43, 67]. The peak incidence is in the 5th decade, with male predominance [20, 26, 67]. The main anatomical spinal site is cauda equina and filum terminale [3, 20, 26, 32, 58, 67]. With such a small number of paraganglioma of the lumbar spine, little is known about this disease.

Complete microsurgical resection remains the first choice. However, on review of the current literature, there is a lack of consensus with regard to clinical management. Firstly, on preoperative imaging, differentiating paraganglioma from other cauda equina tumours is challenging and this might have an impact on the patients’ management. This point has been raised and discussed in a recent review by Honeyman et al. Secondly, some of these tumours are secretory requiring preoperative and intraoperative preparation similar to surgery for carotid body/glomus paragangliomas. Thirdly, there is a lack of consensus about length of follow-up, intraoperative dissemination and recurrence rate especially when complete resection has been achieved.

In an attempt to answer the above questions, we report a consecutive series of surgically treated primary lumbar paragangliomas. We describe the relevant clinical presentation, and radiological and pathological findings together with follow-up, recurrence and outcome. We have also conducted a scoping review of the existing literature. The aim of the scoping review was to search for recurrence following gross total resection and the presence of any secretory features of the tumour or intraoperative complications (hypertensive episodes intraoperatively or whilst in recovery) and to suggest recommendations for follow-up.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study was registered as an audit with our institutional approval (CADB002408). A database for the case series was created by searching the prospectively maintained neuropathology database for paraganglioma for the period September 2004 to December 2016 inclusive. Patients case notes, electronic records and images were searched. We analysed patient age, sex, comorbidities, presenting symptoms/signs, neurological status at presentation (any neurological deficits), time from presentation to surgery, complications, length of hospital stay and follow-up, recurrence and outcome.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies were reviewed. The radiology reports and images were reviewed regarding the level of the lesions, together with their features in term of shape, contour, signal on T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI sequences and enhancement with gadolinium.

The operative documentations were reviewed for the type of procedure, intraoperative findings and intraoperative complications. Anaesthetic charts were analysed for instability or changes in blood pressure intraoperatively. The recovery charts were reviewed for vital signs especially blood pressure changes.

The histopathological features were analysed from the formal histopathology reports macroscopically (shape, colour, consistency and encapsulation), microscopically (cellular arrangement (Zellballen) and immunohistochemically (necrosis, Ki-67 expression, immunostaining for chromogranin A and synaptophysin, CAM 5.2 (cytokeratin), GFAP and S100 where available). Electron microscopy was reviewed regarding the presence of abundant neurosecretory (dense-core) granules or prominence of rough endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus.

Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism version 8.02 for Windows 10, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA.

Search strategy for scoping review

An extensive literature search was undertaken including PubMed, Google Scholar, Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). Searches were limited to articles published between 1990 and 2020 inclusive and written in English only. Search terms were charted to subject headings and combined using Boolean operations. The following keywords were used for search: “paraganglioma”, “human”, “spine, “lumbar”, “sacral”, and “cauda equina”. Abstracts of papers found in the literature search were scrutinised independently by two authors (AS and RI) to assess suitability for inclusion. Reference lists from the papers identified in the literature search were manually searched to ascertain other articles suitable for inclusion. The inclusion criterium was any article that described intradural paraganglioma of the cauda equina or lumbo-sacral region. Those with no full text, non-English, animal/cadaveric studies and non-spinal or lumbo-sacral paraganglioma were excluded.

This scoping review has been reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [66].

Outcome

Outcome was assessed in terms of any improvement of preoperative neurological deficits, back pain or sciatic pain by independent clinicians immediately after surgery and 12 months post-operatively. Patients were contacted for a follow-up assessment if they had not attended in person at 12 months post-operatively. Recurrence was assessed on follow-up imaging. Patients who had complete microsurgical resection of the paraganglioma with no recurrence on follow-up were considered cured.

Synthesis of results

The results in this manuscript are presented as a scoping review, including summary tables, and follow the coming format: patient demographics; presentation and localisation of the tumour; gross total resection and complications; length of follow-up; recurrence and secretory features of the tumour.

Results

Case series

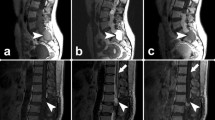

We report ten patients presenting to our institution with non-syndromic primary lumbar paraganglioma between 2004 and 2016, seven males and three females with a mean age of 53.6 ± 5.1 (range 34–71 years). All patients presented with back pain. The remaining constellation of symptoms are summarised in Table 1. The duration of symptoms ranged from 3 months to 6 years. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed intradural lumbar enhancing lesions. Pre-surgical radiological diagnosis included nerve sheath tumour and ependymoma. None of the cases was reported preoperatively as a paraganglioma. Representative images of two cases are presented in Fig. 1. The mean duration from radiological diagnosis or referral to surgical intervention was 23.1 ± 7.7 days (range 0–70 days). Three patients had surgery within 24 h of admission due to worsening pain and neurological function and they all had complete microsurgical excisions. Two cases underwent intraoperative frozen section pathology results which revealed paraganglioma. All tumours were reported to be of vascular nature and found attached to the filum terminale which was divided at the time of surgery. No intraoperative complications were reported.

Representative MRI images of paragangliomas. A–C Patient number 5 (Table 1) images. A) Sagittal T2W image showing the intradural lesion (arrow). B) Sagittal post-contrast (Gadolinium) T1W image demonstrating homogenously enhancing lesion (arrow). C Axial post-contrast (Gadolinium) T1W image demonstrating an intradural homogenously enhancing lesion (arrow). D–F Patient number 9 (Table 1) images. D) Sagittal T2W image suspicious of a spinal lesion (arrow). E) Sagittal post-contrast (Gadolinium) T1W image demonstrating enhancing lesion (arrow). F) Axial post-contrast (Gadolinium) T1W image demonstrating an intradural enhancing lesion (arrow). Please note that in this patient (number 9), the post-contrast MRI was performed at a different date

Histopathological and electron microscopic studies were carried out and confirmed a classic “Zellballen” pattern (Fig. 2), the presence of dense-core neurosecretory granules, prominent rough endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus (Fig. 3). The immunohistochemical studies confirmed that the tumours had low proliferation rates (Ki67 cell counts (< 3%) and profiles compatible with paraganglioma WHO grade 1 (Fig. 2).

Histopathology paraganglioma samples. A) Macro specimen — tissue filled with blood cysts. B) Characteristic rounded groups of cells, polygonal to oval and are arranged in distinctive cell balls called Zellballen. Haematoxylin and eosin, scale bar = 10 microns. C) Diffuse immunostaining for neurosecretory granules synaptophysin, scale bar = 10 microns. D) S100-positive sustentacular cells. Immunostain for S100 and negative for GFAP, scale bar = 10 microns. E) The tumour cells contain cytokeratin. Immunostain for CAM5.2, scale bar = 10 microns. F) There is a low proliferation rate. Immunostain for Ki-67, scale bar = 50 microns

Anaesthetic and recovery charts were reviewed and there was no evidence of either hypertensive episodes or hemodynamic instability. Patients received 24–48 h of dexamethasone (4 or 8 mg twice a day) as per the treating surgeon’s instruction. The mean length of hospital stay was 6 days (range 3–13 days). All patients, except one who required rehabilitation, were discharged home. None of the patients received any adjuvant therapy and we found no recurrence of the tumour after a mean follow-up of 5.1 ± 1.4 years. All patients reported improvements in their back pain, radiculopathy and neurological function (Table 1).

We experienced low complications. One patient developed mild weakness, worsening back pain and sciatica secondary to an epidural haematoma that was evacuated promptly with no adverse effects. Another patient developed a pseudomeningocele that required surgical repair.

Scoping review

Patient demographics and presentation

The review search revealed 620 articles where the title and abstracts were screened and 65 papers (including ours) combining 121 patients (Fig. 4). We have included 51 case reports [1, 2, 5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, 16,17,18,19, 22, 24, 25, 27, 28, 31, 34, 37,38,39,40,41, 44, 45, 47, 48, 50, 52, 53, 55,56,57, 59, 62, 63, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] and 14 case series [4, 15, 20, 21, 30, 49, 51, 58, 60, 61, 67, 68, 78] (Tables 2 and 3). The mean patients’ age was 48.8 ± 1.2 (range 17–75 years).

One hundred and fourteen patients (94%) presented with back pain, and this was the most common symptom. Sensory changes were reported in 34 patients (34%), and in 32 (26%) patients, lower limb weakness was encountered. Bowel and bladder disturbances were documented in 27 patients (22%), and 18 (15%) patients had reduced lower limbs reflexes. Interestingly, eight (6.6%) patients presented with papilloedema and two patients were diagnosed with normal pressure hydrocephalus. The detailed patients’ presentations are described in Tables 2 and 3.

Localisation, surgery and complications

The majority of the tumours were located at the lumbar L1 level or below (Tables 2 and 3). One case was reported in the thoracic spine (at T3) [67]. Although this case was part of one of the case series in the review, we excluded it from the analysis as it is not in the cauda equina region. Gross total resection was reported in 80 cases (66%) and subtotal resection in five cases (4%). There was no data regarding resection in 36 cases (30%). Complications were reported in six cases, such as CSF leak and haematoma (Tables 2 and 3). Two of these are also included in our local series (Table 1).

Follow-up, recurrence and secretory features

The mean follow-up interval was 3.48 ± 0.46 (range 0.15–23 years) in a cohort of 79 cases (including ours).

Data concerning recurrence status was reported in 75 cases (63%). Following surgery, 93% had no tumour recurrence, whilst recurrence was reported in 5 cases (7%) [51, 53, 61, 67, 75] (Table 4). Two patients had subtotal resection [53, 67], one patient had multiple other sacral lesions that had grown requiring surgical intervention [75] and the two other patients had no initial post-surgery MRI scan to confirm the total resection of the tumour [51, 61].

Data about secretory features was available for 96 cases (79%), of which only two cases (2%) were reported to be secretory [5, 21].

The first case was a 62-year-old woman who was also found to be hypertensive [21]. During surgery, she had tachycardia and a rise in blood pressure when manipulating the tumour [21]. The tumour was vascular and clipping of the tumour pedicle facilitated the resection.

The second case with secretory features was a 50-year-old man who was also known to have hypertension, and the MRI revealed a large T12-L2 intradural enhanced lesion with scalloping of the vertebrae [5]. During surgery, the patient had a rise in blood pressure and the tumour was partially resected. Post-operatively, he had flushing all over the body, especially over the face and chest region, palpitations, dysphagia and uncontrolled blood pressure. In spite of intensive care management, he collapsed with haematemesis and died [5].

Discussion

Primary paragangliomas of the spine are rare, slowly growing, benign intradural extra medullary tumours [20, 67].They are most commonly located in the cauda equina and filum terminale [4, 20, 67] representing approximately up to 3.5% of the cauda equina lesions [42]. They are classified as World Health Organization (WHO) grade I tumours, due to their indolent behaviour and histologically benign appearance.

The most common presenting symptom in a patient with a lumbo-sacral paraganglioma is lower back pain with radiculopathy [7, 20, 58, 67]. Lower back pain was reported in 94% of the cases in our review. The lesion often occupies the whole diameter of the spinal canal; yet, it is rare for it to cause a cauda equina syndrome until very late. Severe/permanent sensory and motor deficits are unusual, and incontinence of urine and faeces rarer still. This was evident in our review (Tables 2 and 3). Commonly, presentation and diagnosis are delayed by months to years as shown in our case series (Table 1) which reflects the nonspecific nature of the symptoms. Due to their slow growth, these lesions are less likely to cause cauda equina syndrome. In our case series, only three patients (cases number 1, 7 and 8 in our series (Table 1)) underwent surgery within 24 h due to their presentation as possible cauda equina syndrome and deteriorating neurological function. Cases 1 and 7 had perianal numbness and case 8 had progressive weakness.

The diagnostic procedure of choice for an intradural lesion is MRI, although it should be noted that the MRI findings are nonspecific for these lesions. Paragangliomas are usually isointense to spinal cord on T1-weighted images, hyperintense on T2-weighted images and enhance with gadolinium [15, 54, 58, 67]. Whilst MRI gives accurate anatomical information regarding intradural cauda equina lesions, the differential diagnosis includes schwannoma, ependymoma, meningioma or solitary metastasis [23] and remains difficult to diagnose paraganglioma preoperatively based solely on the MRI findings. Indeed, a recent review described that preoperative radiological diagnosis of these rare tumours can be challenging [26]. In agreement, certainly, in our case series, none of the cases was reported as paraganglioma before surgery.

An important question we aimed to explore in our study was as to whether cauda equina paragangliomas have a secretory function or not. These patients usually lack the classical clinical triad of headache, diaphoresis and tachycardia (with or without palpitations) which is usually seen in cases of pheochromocytoma (however, the secretory function can be addressed preoperatively by investigating the patients for catecholamines). Cauda equina paragangliomas are rare and therefore unlikely to be investigated for catecholamines preoperatively.

The other clue to suggest that the tumour may be a secretory paraganglioma is an intraoperative surge of catecholamines that causes hypertension and tachycardia. This was not encountered in our case series. Searching the literature, we found a handful of cases (including in other spinal locations) with secretory functions and mainly diagnosed intraoperatively [5, 21, 29, 65, 79].

Although the electron microscopic appearances in our case series revealed the presence of secretory granules (Fig. 3), they had no preoperative, intraoperative or post-operative symptomatology to suggest catecholamine release. This suggests that these lesions are in fact non-functional tumours. Furthermore, unlike pheochromocytoma, sympathetic paragangliomas rarely secrete adrenaline, since the enzyme needed to convert norepinephrine to adrenaline (phenylethylamine N-methyltransferase) is expressed exclusively in the adrenal glands [33].

Our series and literature search suggest that it is highly unlikely that an intradural cauda equina paraganglioma behaves like pheochromocytoma and perhaps should not be treated as such. If hypertension and tachycardia are encountered intraoperatively, then clipping the tumour pedicle is helpful in controlling catecholamine surge as described previously [21].

Paragangliomas are indolent WHO grade I lesions [35, 36]. They are usually soft, red, vascular and well-circumscribed masses (Fig. 2A), usually arising from the filum terminale and less commonly from a nerve root. They may be attached to the conus medullaris or to the adjacent nerve roots. As such, microsurgical separation may be difficult. Most commonly the tumour is well-encapsulated and complete resection is accomplished. In our case series, all tumours were found originating from the filum terminale. The primary treatment for cauda equina paraganglioma is complete microsurgical resection which should result in patients’ cure. Similar to other recent large case series [20], we had no recurrence after complete surgical resection after a mean follow-up of 5.1 ± 1.4 years. Overall, we found a 7% recurrence rate in the literature over the years, and in some cases, this was part of an aggressive and metastatic process [53]. Other cases had subtotal resection of the tumour (Table 4), and no initial post-surgery MRI was performed to confirm complete resection of the tumour in the rest (Table 4). We acknowledge that a very small number of recurrences has been reported in the literature [26], and others may recommend longer follow-up period. Following this study, our most recent practice is to follow up the patients in clinic and to perform an initial follow-up scan usually in 3–6 months and discharge if complete microsurgical resection is confirmed.

Although the vast majority of these cases do not recur following complete microsurgical resection that is confirmed on a follow-up MRI scan, the length of follow-up should be on a case by case ground and at the discretion of the treating surgeon.

Limitations

These results come with the limitations of a retrospective study. The number of cases we report is small. We attempted to increase the number of cauda equina paraganglioma cases by performing a scoping-analysis; however, many of those are case reports and the rest are small case series. This is challenging perhaps due to the nature of the pathology studied.

Conclusions

Cauda equina paraganglioma is a rare, benign but treatable pathology with very good outcomes. Very rarely they release catecholamines, in our review, we found only two cases. Total microsurgical resection likely provides cure for the patients without the need for adjuvant therapy or prolonged follow-up. However, in certain situations, the length of follow-up should be determined by the treating surgeon.

Data availability

Researchers can apply for access to anonymized data from the present study for well-defined research questions. Please contact the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Adriani KS, Stenvers DJ, Imanse JG (2012) Pearls & oy-sters: lumbar paraganglioma: can you see it in the eyes? Neurology 78:e27-28. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182436586

Aggarwal S, Deck JH, Kucharczyk W (1993) Neuroendocrine tumor (paraganglioma) of the cauda equina: MR and pathologic findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 14:1003–1007

Aghakhani N, George B, Parker F (1999) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina region–report of two cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 141:81–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007010050269

Aghakhani N, George B, Parker F (1999) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina region–report of two cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir 141:81–87

Agrawal V, Rahul M, Khan S, Vernon V, Rachana B (2012) Functional paraganglioma: a rare conus-cauda lesion. J Surg Tech Case Rep 4:46–49. https://doi.org/10.4103/2006-8808.100355

Ashkenazi E, Onesti ST, Kader A, Llena JF (1998) Paraganglioma of the filum terminale: case report and literature review. J Spinal Disord 11:540–542

Bannykh S, Strugar J, Baehring J (2005) Paraganglioma of the lumbar spinal canal. J Neurooncol 75:119

Bhatia R, Jaunmuktane Z, Zrinzo A, Zrinzo L (2013) Caught between a disc and a tumour: lumbar radiculopathy secondary to disc herniation and filum paraganglioma. Acta Neurochir 155:315–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-012-1537-4

Boukobza M, Foncin JF, Dowling-Carter D (1993) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina: magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroradiology 35:459–460

Bozkurt G, Ziyal IM, Akbay A, Dal D, Can B, Ozcan OE (2005) Cauda-filar paraganglioma with ‘silk cocoon’ appearance on spinal angiography. Acta Neurochir 147:99–100; discussion 100

Bush K, Bateman DE (2014) Papilloedema secondary to a spinal paraganglioma. Pract 14:179–181. https://doi.org/10.1136/practneurol-2013-000620

Caccamo DV, Ho KL, Garcia JH (1992) Cauda equina tumor with ependymal and paraganglionic differentiation. Hum Pathol 23:835–838

Chou SC, Chen TF, Kuo MF, Tsai JC, Yang SH (2016) Posterior vertebral scalloping of the lumbar spine due to a large cauda equina paraganglioma. Spine J 16:e327–e328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2015.11.048

Corinaldesi R, Novegno F, Giovenali P, Lunardi T, Floris R, Lunardi P (2015) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina region. Spine J 15:e1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2014.10.021

Demircivi Ozer F, Aydin M, Bezirciglu H, Oran I (2010) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina: a highly vascular tumour. J Clin Neurosci 17:1445–1447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2009.12.026

Dillard-Cannon E, Atsina KB, Ghobrial G, Gnass E, Curtis MT, Heller J (2016) Lumbar paraganglioma. J Clin Neurosci 30:149–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2016.01.019

Djindjian M, Ayache P, Brugieres P, Malapert D, Baudrimont M, Poirier J (1990) Giant gangliocytic paraganglioma of the filum terminale. Case Rep J Neurosurg 73:459–461

Erban T, Erban N, Midi A, Yener N, Cubuk R, Sav A (2010) Cauda equina paraganglioma with ependymal morphology: a rare case report. Eur J Med Res 1:138

Faro SH, Turtz AR, Koenigsberg RA, Mohamed FB, Chen CY, Stein H (1997) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina with associated intramedullary cyst: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 18:1588–1590

Fiorini F, Lavrador JP, Vergani F, Bhangoo R, Gullan R, Reisz Z, Al-Sarraj S, Ashkan K (2020) Primary lumbar paraganglioma: clinical, radiological, surgical and histopathological characteristics from a case series of 13 patients. World Neurosurg 23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.144

Gelabert-Gonzalez M (2005) Paragangliomas of the lumbar region. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine 2:354–365

Hardten DR, Wen DY, Wirtschafter JD, Sung JH, Erickson DL (1992) Papilledema and intraspinal lumbar paraganglioma. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 12:158–162

Henaux PL, Zemmoura I, Riffaud L, Francois P, Hamlat A, Brassier G, Morandi X (2011) Surgical treatment of rare cauda equina tumours. Acta Neurochir 153:1787–1796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-011-1094-2

Herman M, Pozzi-Mucelli RS, Skrap M (1998) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina: case report and review of the MRI features. Acta Univ Palacki Olomuc Fac Med 141:27–30

Hilmani S, Ngamasata T, Karkouri M, Elazahri A (2016) Paraganglioma of the filum terminale mimicking neurinoma: case report. Surg Neurol Int 7:S153–S155. https://doi.org/10.4103/2152-7806.177892

Honeyman SI, Warr W, Curran OE, Demetriades AK (2019) Paraganglioma of the lumbar spine: a case report and literature review. Neurochirurgie 65:387–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuchi.2019.05.010

Hong JY, Hur CY, Modi HN, Suh SW, Chang HY (2012) Paraganglioma in the cauda equina. A case report Acta Orthop Belg 78:418–423

Iliya AR, Davis RP, Seidman RJ (1991) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina: case report with magnetic resonance imaging description. Surg Neurol 35:366–367

Jeffs GJ, Lee GY, Wong GT (2003) Functioning paraganglioma of the thoracic spine: case report. Neurosurgery 53:992–994; discussion 994–995. doi:https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000084082.08940.7f

Kimura N, Toyama Y, Ishimura M, Murota M, Fukunaga K, Nishiyama Y (2011) Paragangliomas in the cauda equina region: radiological findings in three cases. Neuroradiology 53(10):819. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-011-0906-7

Lalloo ST, Mayat AG, Landers AT, Nadvi SS (2001) Clinics in diagnostic imaging (68). Intradural extramedullary spinal paraganglioma. Singapore Med J 42:592–595

Landi A, Tarantino R, Marotta N, Rocco P, Antonelli M, Salvati M, Delfini R (2009) Paraganglioma of the filum terminale: case report. World J Surg Oncol 7:95. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-7-95

Lenders JW, Pacak K, Walther MM, Linehan WM, Mannelli M, Friberg P, Keiser HR, Goldstein DS, Eisenhofer G (2002) Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: which test is best? JAMA 287:1427–1434. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.11.1427

Li P, James SL, Evans N, Davies AM, Herron B, Sumathi VP (2007) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Clin Radiol 62:277–280

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P (2007) The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 114:97–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131:803–820. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1

Mahalingashetti PB, Bylappa SK, Jyothi AV, Subramanian RA (2012) Paraganglioma of cauda equina. Clin Cancer Investig J 1:35–36. https://doi.org/10.4103/2278-0513.95019

Marcol W, Kiwic G, Malinowska-Kolodziej I, Kotulska K, Kotas A, Adamek D, Wysokinski T (2009) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina presenting with erectile and sphincter dysfunction. J Chin Med Assoc 72:328–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70380-6

Matschke J, Westphal M, Lamszus K (2005) November 2004: intradural mass of the cauda equina in a woman in her early 60s. Brain Pathol 15(169–170):173

Mendez JC, Carrasco R, Prieto MA, Fandino E, Blazquez J (2019) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina: MR and angiographic findings. Radiol Case Rep 14:1185–1187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radcr.2019.06.011

Midi A, Yener AN, Sav A, Cubuk R (2012) Cauda equina paraganglioma with ependymoma-like histology: a case report. Turk 22:353–359. https://doi.org/10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.3389-10.1

Miliaras GC, Kyritsis AP, Polyzoidis KS (2003) Cauda equina paraganglioma: a review. J Neurooncol 65:177–190

Mishra T, Goel NA, Goel AH (2014) Primary paraganglioma of the spine: a clinicopathological study of eight cases. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine 5:20–24. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-8237.135211

Murrone D, Romanelli B, Vella G, Ierardi A (2017) Acute onset of paraganglioma of filum terminale: a case report and surgical treatment. Int J Surg Case Rep 36:126–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.05.016

Mylonas C (1992) Case report: paraganglioma of the cauda equina. Clin Radiol 46:139–141

Neumann HPH, Young WF Jr, Eng C (2019) Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. N Engl J Med 381:552–565. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1806651

Paleologos TS, Gouliamos AD, Kourousis DD, Papanicolaou P, Vlahos C, Kyriakou T (1998) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina: a case presenting features of increased intracranial pressure. J Spinal Disord 11:362–365

Parthiban JKBC, Murugan KS (2004) Unusual MRI appearance of paraganglioma of the cauda equina. Case Rep Riv Neuroradiol 17:699–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/197140090401700512

Pigott TJD, Lowe JS, Morrell K, Kerslake RW (1990) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina. Rep Three Cases J Neurosurg 73:455–458. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1990.73.3.0455

Pytel P, Krausz T, Wollmann R, Utset MF (2005) Ganglioneuromatous paraganglioma of the cauda equina - a pathological case study. Hum Pathol 36:444–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2005.01.024

Raftopoulos C, Flament-Durand J, Brucher JM, Stroobandt G, Chaskis C, Brotchi J (1990) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina. Report of 2 cases and review of 59 cases from the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 92:263–270

Rhee HY, Jo DJ, Lee JH, Kim SH (2010) Paraganglioma of the filum terminale presenting with normal pressure hydrocephalus. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 112:578–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.04.004

Roche PH, Figarella-Branger D, Regis J, Peragut JC (1996) Cauda equina paraganglioma with subsequent intracranial and intraspinal metastases. Acta Neurochir 138:475–479

Rosero DS, Alfaro J, Del Agua C, Mejia E, Eizaguirre B, Vicente S, Alastuey M, Valero A, Rivero D (2013) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina. Cytological, histological and immunohistochemical study. Clin Neuropathol 32 (6):540. doi:https://doi.org/10.5414/NPP32536

Sable MN, Nalwa A, Suri V, Singh PK, Garg A, Sharma MC, Sarkar C (2014) Gangliocytic paraganglioma of filum terminale: report of a rare case. Neurol India 62:543–545. https://doi.org/10.4103/0028-3886.144456

Sankhla S, Khan GM (2004) Cauda equina paraganglioma presenting with intracranial hypertension: case report and review of the literature. Neurol India 52:243–244

Satyarthee GD, Garg K, Borkar SA (2017) Paraganglioma of the filum terminale: an extremely uncommon neuroendocrine neoplasm located in spine. J Neurosci Rural Pract 8:490–493. https://doi.org/10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_477_16

Seidou F, Tamarit C, Sevestre H (2020) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina region: report of 9 cases Paragangliome de la queue de cheval: a propos d’une serie de 9 cas. Ann Pathol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annpat.2020.02.018

Sharma A, Gaikwad SB, Goyal M, Mishra NK, Sharma MC (1998) Calcified filum terminale paraganglioma causing superficial siderosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 170:1650–1652

Simsek M, Onen MR, Zerenler FG, Kir G, Naderi S (2015) Lumbar intradural paragangliomas: report of two cases. Turk 25:162–167. https://doi.org/10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.9303-13.4

Singh NG, Sarkar C, Sharma MC, Garg A, Gaikwad SB, Kale SS, Mehta VS (2005) Paraganglioma of cauda equina: report of seven cases. Brain Tumor Pathol 22:15–20

Slowinski J, Stomal M, Bierzynska-Macyszyn G, Swider K (2005) Paraganglioma of the lumbar spinal canal - case report. Folia Neuropathol 43:119–122

Steel TR, Botterill P, Sheehy JP (1994) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina with associated syringomyelia: case report. Surg Neurol 42:489–493

Suarez C, Rodrigo JP, Bodeker CC, Llorente JL, Silver CE, Jansen JC, Takes RP, Strojan P, Pellitteri PK, Rinaldo A, Mendenhall WM, Ferlito A (2013) Jugular and vagal paragangliomas: systematic study of management with surgery and radiotherapy. Head Neck 35:1195–1204. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.22976

Toyota B, Barr HW, Ramsay D (1993) Hemodynamic activity associated with a paraganglioma of the cauda equina. Case Rep J Neurosurg 79:451–455. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1993.79.3.0451

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tuncalp O, Straus SE (2018) PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169:467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Tuleasca C, Al-Risi AS, David P, Adam C, Aghakhani N, Parker F (2020) Paragangliomas of the spine: a retrospective case series in a national reference French center. Acta Neurochir 162:831–837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-019-04186-8

Turkkan A, Kuytu T, Bekar A, Yildirim S (2019) Nuances to provide ideas for radiologic diagnosis in primary spinal paragangliomas: report of two cases. Br J Neurosurg 33:210–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688697.2017.1368452

Undabeitia-Huertas J, Noboa R, Jove R, Boix M, Gatius S, Nogues Y (2013) Cauda equina syndrome caused by paraganglioma of the filum terminate Paraganglioma del filum terminal como causa de sindrome de cauda equina. An Sist Sanit Navar 36:347–351

Vats A, Prasad M (2019) Spinal paraganglioma presenting as normal pressure hydrocephalus: a rare occurrence. Br J Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688697.2019.1643007

Vural M, Arslantas A, Isiksoy S, Adapinar B, Atasoy M, Soylemezoglu F (2008) Gangliocytic paraganglioma of the cauda equina with significant calcification: first description in pediatric age. Zentralbl Neurochir 69:47–50. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-985162

Walsh JC, O’Brien DF, Kumar R, Rawluk D (2005) Paraganglioma of the cauda equina: a case report and literature review. Surg 3:113–116

Wang YF, Guo WY, Huang CI, Ho DMT, Teng MMH, Chan CY (2000) Paraganglioma of the filum terminale: a case report. Chin J Radiol 25:165–168

Wang ZH, Wang YT, Cheng F, Hu Y (2018) Pathological features of paraganglioma in the lumbar spinal canal: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 97:e12586. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000012586

Warrier S, Owler BK, Besser M (2006) Paraganglioma and paragangliomatosis of the cauda equina. ANZ J Surg 76:1033–1037

Wester DJ, Falcone S, Green BA, Camp A, Quencer RM (1993) Paraganglioma of the filum: MR appearance. J Comput Assist Tomogr 17:967–969

Yaldiz C, Ceylan D, Kacira T, Kacira OK, Kahyaoglu Z (2016) Primary lumbarspinal paraganglioma: a case report with literature review of last 10 years. Neurosurg Q 26:266–269. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNQ.0000000000000164

Yang SY, Jin YJ, Park SH, Jahng TA, Kim HJ, Chung CK (2005) Paragangliomas in the cauda equina region: clinicopathoradiologic findings in four cases. J Neurooncol 72:49–55

Zileli M, Kalayci M, Basdemir G (2008) Paraganglioma of the thoracic spine. J Clin Neurosci 15:823–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2006.07.024

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lucy Sinclair, Information Specialist, Royal College of Surgeons of England Library and Archives Team, for conducting the literature searches.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: AS. Pathological revision: LRB. Clinical data collection and analysis: AS, RI. Data analysis and interpretation: AS, RI, LRB, SH, SS, FGJ. Manuscript writing: AS, RI, FGJ. Final approval of manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This retrospective cohort study is registered as an audit with our institutional approval (CADB002408). No identifiable data is presented.

Consent to participate

No informed consent was required, as this is a retrospective analysis without any traceable patient data. Not applicable for the systematic review either.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Anan Shtaya and Robert Iorga share the first authorship.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shtaya, A., Iorga, R., Hettige, S. et al. Paraganglioma of the cauda equina: a tertiary centre experience and scoping review of the current literature. Neurosurg Rev 45, 103–118 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-021-01565-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-021-01565-7