Abstract

Foramen magnum meningiomas are challenging tumors, requiring special considerations because of the vicinity of the medulla oblongata, the lower cranial nerves, and the vertebral artery. After detailing the relevant anatomy of the foramen magnum area, we will explain our classification system based on the compartment of development, the dural insertion, and the relation to the vertebral artery. The compartment of development is most of the time intradural and less frequently extradural or both intraextradural. Intradurally, foramen magnum meningiomas are classified posterior, lateral, and anterior if their insertion is, respectively, posterior to the dentate ligament, anterior to the dentate ligament, and anterior to the dentate ligament with extension over the midline. This classification system helps to define the best surgical approach and the lateral extent of drilling needed and anticipate the relation with the lower cranial nerves. In our department, three basic surgical approaches were used: the posterior midline, the postero-lateral, and the antero-lateral approaches. We will explain in detail our surgical technique. Finally, a review of the literature is provided to allow comparison with the treatment options advocated by other skull base surgeons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Meningiomas are common neoplasms representing 14.3 to 19% of all intracranial tumors [63]. Among all the meningiomas, only 1.8 to 3.2% arises at the foramen magnum (FM) level [3]. Nevertheless, meningiomas are the most commonly observed FM tumors, representing 70% of all benign tumors [13, 15–19, 55, 64]. Most of the time, these are strictly intradural. Ten percent have an extradural extension: Most are intra- and extradural, and a few may be entirely extradural [9, 13, 15–19, 24, 25, 56, 60, 61].

The lesion is often large when discovered because of their slow-growing rate, their indolent development, the difficulty of the diagnosis leading to a long interval since the first symptom, and the wide subarachnoid space at this level [7].

The prerequisite for treating FM meningiomas (FMMs) is the perfect knowledge of the surgical anatomy. We will then first detail a comprehensive review of the relevant anatomy of the FM area with special emphasis on the vertebral artery (VA) V3 and V4 segments. Second, we will describe our classification system. This classification system helps for determining the best surgical approach and for anticipating the position of lower cranial nerves. The technical aspects of our surgical approaches will then be detailed extensively. Finally, we provide a summary of the relevant literature, detailing surgical results and surgical approaches advocated by other skull base surgeons and discussing the extent of bone resection and the need for fusion.

Surgical anatomy

Limits of the FM

A meningioma is considered to be located into the FM region if its insertion zone is mainly situated into the FM area. According to the FM limits that we have previously used, the FM area is defined by these landmarks [13, 18, 19] (Fig. 1):

-

Anterior border: lower third of the clivus and upper edge of the body of C2

-

Lateral borders: jugular tubercles and upper aspect of C2 laminas

-

Posterior border: anterior edge of the squamous occipital bone and C2 spinous process

Illustration of the foramen magnum anatomy through a postero-lateral approach. The skin incision (dotted line) extends on the midline just upper to the occipital protuberance and curves laterally toward the pathological side. The right vertebral artery has been elevated from the C1 posterior arch. The C1 posterior arch has been resected on the pathological side, and a suboccipital craniectomy has been performed. The dura matter has been opened. 1 CN IX–X–XI, 2 PICA, 3 CN XII, 4 vertebral artery V4 segment, 5 C1, 6 dentate ligament, 7 vertebral artery V3 segment

The VA V3 and V4 segments

The VA V3 and V4 segments are important vascular structures whose anatomy must be perfectly known when approaching FMMs.

In fact, after piercing the lateral aspect of the occipito-atlantal dura mater, the VA V3 segment becomes the V4 segment and then joins the contralateral one to form the basilar artery [8].

The VA V3 segment anatomy and techniques of approach, exposure, and transposition have been extensively described [8]. In summary, the VA V3 segment, also called the “suboccipital segment,” extends from the C2 transverse process to the FM dura mater. Its course is divided in three portions: a vertical portion, between the transverse processes of C2 and C1, a horizontal portion in the groove of the posterior arch of the atlas, and an oblique portion on leaving this groove up to the dura mater [8].

Along its course, this VA V3 segment can be at the origin of small collateral branches: in the middle of the posterolateral aspect of the C1–C2 portion, corresponding to the C2 radicular artery, a small muscular branch coursing posteriorly at the upper exit of the C1 transverse foramen, the posterior meningeal artery, and the posterior spinal artery, just before its dural penetration. This last branch enters the dural foramen where the C1 nerve root exits the spinal canal [50] and can also be bound with the VA by fibrous dural bands. The posterior spinal artery may also arise from the initial intradural part of the VA V4 segment or from the posteroinferior cerebellar artery (PICA) [11, 33, 43, 50]. Then, this branch runs medially behind the most rostral attachment of the dentate ligament [50]. On reaching the lower medulla, it divides into ascending and descending branches, providing, respectively, the vascular supply to a part of the medulla oblongata and the spinal cord [50]. The VA V3 segment is surrounded by a periosteal sheath that invaginates into the dura when piercing the FM lateral dura, thus creating a double furrow for 3–4 mm. In fact, the periosteal sheath is in continuity with the outer layer of the dura. At this level, the VA is attached to the periosteal sheath, and the adventitia is adherent to the double furrow forming a sort of distal fibrous ring [8]. In such a way, despite being the most mobile segment, the VA V3 segment is fixed at its extremities.

Anatomical relations of the VA are modified by head movements of rotation, as well as during surgical positioning. In neutral position, the vertical and horizontal portions of the V3 segment are perpendicular. On the contrary, after head rotation, as required during an anterolateral approach, both segments are stretched and run parallel, only separated by the posterior arch of the atlas, because the C1 transverse process is pushed anteriorly by this movement, away from the C2 transverse process [8].

Abnormalities of the VA V3 segment are important to know and to identify preoperatively:

-

In 40% of the subjects, the VAs size is different: One side is dominant, and the other is hypoplastic or atretic [8].

-

The VA V3 segment can end at the PICA or at the occipital artery [12]. In 20% of the cases, the PICA originates extracranially, arising from the VA above C1, between C1 and C2, or even in the V2 segment [29, 36].

-

The VA V3 segment can have an intradural course that corresponds to a VA duplication: One atretic portion follows the normal course, but the main portion pierces the dura between C1 and C2 [23, 26, 30, 40, 53].

-

A proatlantal artery consists of a persistent congenital anastomosis between the carotid artery and the VA; it is often associated with an atretic proximal VA and an extracranial origin of the PICA [12, 36, 48].

-

Finally, the groove of the arch of the atlas can be turned into a tunnel if the occipitoatlantal membrane is calcified or ossified, raising some difficulties to expose the horizontal portion at this level [23, 47].

The VA V4 segment ascends from the dura up to the anterior aspect of the pontomedullary sulcus where it joins the controlateral one to form the basilar artery. Initially, the VA V4 segment faces posteriorly and medially the occipital condyle, the hypoglossal canal, and the jugular tubercle. Later, the VA V4 segment lies on the clivus and runs in front of the hypoglossal and the lower cranial nerves rootlets.

At the FM level, the VA V4 segment is at the origin of several branches: the PICA, the anterior spinal artery, the anterior and posterior meningeal arteries.

The PICA is the main VA branch and originates at, above, or below the FM level [56]. The anterior spinal artery starts near the vertebrobasilar junction. Most of the time, the anterior spinal arteries of both sides joins together above the FM level near the lower end of the olives, before descending through the FM and running on the anterior midline [56]. In some cases, one artery is dominant, or no fusion exists between both arteries, only one of these arteries forming the anterior spinal artery.

The vascular supply of the FM dura originates from the anterior and posterior VA meningeal branches and the meningeal branches of the ascending pharyngeal and occipital arteries [11, 42, 50]. Infrequently, meningeal branches are coming from the PICA, the posterior spinal artery, and the VA V4 segment. The anterior meningeal branch arises from the VA at the level of the third interspace. The posterior meningeal artery originates from the VA posterosuperior aspect when turning around the lateral mass of the atlas, above the posterior arch of the atlas, just before penetrating the dura, or just at the beginning of the V4 segment [8, 11, 50]. The ascending pharyngeal artery, a branch of the external carotid artery, gives meningeal branches passing into the hypoglossal canal and the jugular foramen. The meningeal branch of the occipital artery is inconstant and runs through the mastoid emissary foramen [50].

Lower cranial nerves

The glossopharyngeal (CN IX), vagus (CN X), and spinal accessory (CN XI) nerves arise from rootlets of the postolivary sulcus and join the jugular foramen, passing ventral to the choroid plexus protruding from the foramen of Luschka and dorsal to the VA [49].

The accessory nerve is composed of rootlets originating from the spinal cord and the medulla. Spinal rootlets join together to form the main trunk, which ascends through the FM running behind the dentate ligament and unites with the upper medullary rootlets. Anastomoses with the dorsal roots of the upper cervical nerves are frequent, that with the C1 nerve root being the most common and largest one [49]. The upper medullary rootlets penetrate directly the jugular foramen [49].

The hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) arises from rootlets of the preolivary sulcus. This nerve runs anterolateral through the subarachnoid space and pass behind the VA to reach the hypoglossal canal. Rarely, the VA separates the CN XII rootlets [49].

The dentate ligament

The dentate ligament is a white fibrous sheet that extends from the pia mater, medially, to the dura mater, laterally. It forms arches leaving passage to the VA for the first one and the second cervical nerve root for the second one.

Our classification system of foramen magnum meningiomas

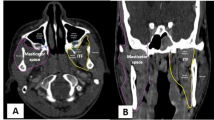

Meningiomas are considered to be located in the FM area if their base of insertion is mainly located within the FM limits. This definition excludes tumors invading secondarily the FM region (Figure 2).

Classification of foramen magnum meningiomas. Foramen magnum meningiomas are classified according to their compartment of development, their dural insertion, and their relation to the vertebral artery. The relation to the vertebral artery permits to anticipate the displacement of the lower cranial nerves. Tumors growing below the vertebral artery push the lower cranial nerves at the superior aspect of the lesion. On the other hand, tumors developed above or on both sides of the vertebral artery displace the lower cranial nerves in all directions and their position can then not be anticipated. Three basic surgical approaches are used. The extent of bone removal is delimited by the dotted lines

The definitive objective of a classification system is to define preoperatively the surgical strategy based on preoperative imaging characteristics of the lesion. The surgical strategy in cases of FMMs is the surgical approach but also the anticipation of modified vital structure position.

In our classification system, FMMs can be classified according to their compartment of development, their dural insertion, and to their relation to the VA [18].

According to the compartment of development, FMMs can be subdivided in:

-

Intradural

-

Extradural

-

Intra- and extradural

Intradural meningiomas are the most commonly observed. Extradural meningiomas like at any other locations are very invasive, into the bone, the nerves and vessels sheaths, and soft tissues. The VA sheath and even its adventitia can also be infiltrated. This raises some difficulties and explains the higher incidence of incomplete removal as compared to intradural meningiomas [31, 32, 39, 56, 60, 62].

According to the insertion on the dura, FMMs can be defined in the antero-posterior plane as:

-

Anterior, if insertion is on both sides of the anterior midline

-

Lateral, if insertion is between the midline and the dentate ligament

-

Posterior, if insertion is posterior to the dentate ligament

Anterior meningiomas push the spinal cord posteriorly. Therefore, the surgical opening between the neuraxis and the FM lateral wall is narrow, and the drilling must extend to the medial part of the FM lateral wall to improve the access. In almost every case, no drilling of the lateral mass of the atlas and occipital condyle is necessary. Exceptionally, anterior meningiomas of small size without anterior compartment enlargement need more bone resection but never includes more than one fifth of these elements. On the other hand, lateral meningiomas displace the neuraxis posterolaterally and widely open the surgical access; therefore, the drilling has never to be extended into the lateral mass of the atlas or the occipital condyle.

Finally, surgical strategies vary according to the relation to the VA, FMM having the possibility to develop:

-

Above the VA

-

Below the VA

-

On both sides of the VA

Meningiomas are more often located below the VA. In this case, the lower cranial nerves are always pushed cranially and posteriorly. There is no need to look for them. They will come into view on reaching the superior tumoral part. On the other hand, if the lesion grows above the VA, the position of the lower cranial nerves cannot be anticipated; the nerves may be displaced separately in any direction. After partial debulking of the tumor, one has to look for them so as to identify and protect them during the tumor resection. In case of tumoral development on both sides of the VA, a similar problem may exist with the position of the lower cranial nerves. Moreover, the dura around the VA penetration may be infiltrated by the tumor. As previously mentioned, the dura is normally adherent to the adventitia, and complete resection of the tumor at this level is hazardous. In this case, which is rarely observed, it may be safer to leave a cuff of infiltrated dura around the VA and to coagulate this zone.

Surgical aspects

Preoperative and perioperative considerations

Standard preoperative workup includes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scan, and sometimes angiography.

On MRI, gadolinium-enhanced sequences help to precisely delimit the dural attachment zone, the tumor, and its relation to neural and vascular structures. On T2-weighted images, the presence of an arachnoid plane between the tumor and the neuraxis is sometimes visible.

Bone windows CT scan is helpful in case of extradural extension to investigate bone erosion and to schedule preoperatively the need for fusion.

Conventional angiography is generally useless. There are only two indications for preoperative angiography:

-

1.

If a highly vascularized tumor is suspected and embolization is contemplated

-

2.

To perform a balloon occlusion test in case of VA encasement (extradural or recurrent meningioma and meningioma inserted around the VA). In our experience, it has never been necessary to occlude the VA.

Intraoperative neurophysiological monitorings have been used by several surgeons [3, 7] and includes somatosensory-evoked potentials, brainstem auditory-evoked potentials, and electromyographic monitoring of lower cranial nerves, by recordings through an endotracheal tube (CN X) and with a needle in the sterno-mastoid (SM) muscle (CN XI) and the tongue (CN XII).

Surgical approaches and techniques at Lariboisière Hospital

The midline posterior approach

The midline posterior approach is indicated for posterior meningiomas, whatever their intra- and extradural extension, if they remain posterior to the plane of the dentate ligament and medial to the VA [15–17]. In such cases, the neuraxis is pushed anteriorly.

The patient may be in the sitting, ventral, or lateral position. To decrease venous bleedings, the sitting position is preferred at Lariboisière Hospital as far as there is no contraindication such as a patent foramen ovale; air embolism is prevented by hypervolemia and G-suit.

The skin is incised on the midline from the occipital protuberance down to the upper cervical region. The midline avascular plane is opened between the posterior muscles, up to the occipital protuberance and down to the spinous process of C2. Bone opening is performed using a drill and Kerrison rongeurs and is always limited to the lower part of the occipital bone and the posterior arch of the atlas. The dura is then incised in a T- or Y-shaped fashion and retracted with stitches.

Postero-lateral approach

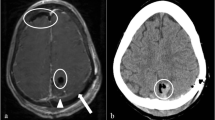

The postero-lateral approach is preferred for any intradural process located laterally and/or anteriorly to the neuraxis and for extradural lesions developed on the posterior part of the lateral FM wall [15–17]. For tumors extending far beyond the anterior midline, the postero-lateral approach has the advantage to allow a bilateral approach in the same stage (Fig. 3, 4, and 5).

a–c Preoperative MRI. A large lateral foramen magnum meningioma displaces the neuraxis. d, e Postoperative CT scan. The meningioma has been completely resected. The spinal cord has regained a normal shape. f Reconstructed 3D CT scan after contrast administration. The resection of the posterior arch of the atlas is visible on the right side. The lateral mass of the atlas (star) was left intact. The vertebral artery (arrow) has been elevated from the C1 posterior arch (compare with the left side) during the dissection

Surgical steps during a postero-lateral approach. a The left vertebral artery V3 segment (black arrow) has been elevated from the lateral part of the C1 posterior arch (white arrowhead). The medial portion has been resected up to the midline (black arrowhead). The dural entrance of the vertebral artery, where the V3 segment becomes the V4 one, is delineated by the dotted line. b The dura matter has been incised. The inferior contraincision extends inferiorly to the site of entrance of the vertebral artery into the dura matter. The C1 posterior rootlets are identified (black arrowhead). The inferior portion of the meningioma (white star) severely compresses the spinal cord (black star). c The vertebral artery V4 segment (white arrow), the spinal accessory nerve (black arrowheads), and the XIIth cranial nerve (white arrowhead) have been controlled. Of note, the dura matter (black star) is stretched over the left C1 lateral mass by a stitch to enlarge the lateral access and after the occipital craniotomy, the fall of the left cerebellum is prevented by a blade (white star). d After the complete removal of the meningioma, both vertebral arteries are visible. On the left side, we observe the section of a feeding vessel (white arrow). The right PICAs is visible (black arrow) as well as the Xth (black star) and the XIIth (black arrowhead) cranial nerves

The postero-lateral approach is a lateral extension of the midline posterior approach. The patient must be carefully positioned in the same position as during a posterior midline approach. The head must be placed in neutral position. Any flexion must be avoided because it decreases the space in front of the neuraxis and therefore may worsen the compression and the neurological condition. The vertical midline skin incision is identical, but the incision is curved laterally on the tumoral side just below the occipital protuberance toward the mastoid process. The posterior muscles are divided along the occipital crest and retracted laterally to expose the occipital bone, the posterior arch of the atlas, and the C2 lamina, if required. The exposure may be extended on a limited way on the contralateral side.

VA exposure

At this step, the VA running above C1 needs to be exposed to safely resect the C1 posterior arch up to the C1 lateral mass. The exposure of the horizontal segment of the VA V3 segment progresses from the midline of the posterior arch of the atlas laterally toward the atlas groove. The medial border of the groove is clearly marked by a step with a decrease in the height of the posterior arch. The safest way to expose the VA is to dissect strictly in the subperiosteal plane. The periosteum of the C1 posterior arch needs to be elevated from medial to lateral and inferiorly to superiorly. Working in this manner permits to expose the posterior aspect of the posterior arch of the atlas, to bring into view the step at the medial end of the groove and then to elevate the VA from the atlas groove. In fact, the VA V3 segment is surrounded by a venous plexus; both artery and veins are enclosed in a periosteal sheath. Both provide protection against VA damage. If tearing occurs, venous bleedings can be controlled by direct bipolar coagulation on the VA periosteal sheath. Dissection at the superior aspect of the VA is more difficult because there is no good landmark and the periosteal sheath is in continuity with the ligaments covering the occipital condyle. Cutting of the ligaments must proceed a few millimeters above the VA on the occipital condyle by following the superior aspect of the VA sheath. The occipitoatlantal membrane covering the groove of the posterior arch of the atlas can be calcified or ossified, turning the groove into a tunnel, raising some difficulties to expose the horizontal portion at this level [23, 47]. After being fully exposed, the VA can be gently displaced superiorly to show the lateral mass of the atlas.

Bone opening

The posterior arch of the atlas is resected with rongeurs from the midline toward the transverse process. To obtain a decompression of the neuraxis before the tumoral resection, the posterior arch of the atlas must also be resected beyond the midline toward the controlateral side. By this way, hyperpressure induced even by gentle manipulation during resection are not transmitted to the neuraxis. The lower part of the occipital bone is drilled or resected with rongeurs laterally toward the sigmoid sinus and also beyond the midline.

The lateral extension of the bone opening is established according to the position of the meningioma. In case of lateral meningiomas, the spinal cord is displaced toward the contralateral side, and then any resection of the FM lateral wall is not necessary. In case of anterior meningiomas, the spinal cord is pushed posteriorly, and the surgical corridor has to be enlarged laterally by drilling up to the medial side of the C1 lateral mass and/or the occipital condyle. Drilling further the lateral mass of the atlas or the occipital condyle is exceptionally necessary. In the exceptional case where the opening must be enlarged, no more than 20% of the medial part of the FM lateral wall has to be drilled. In such a way, stabilization is never required.

The cranio-caudal bone resection is scheduled according to the position of the tumor regarding to the VA. The drilling has to be extended toward the lateral mass of the atlas if the tumor grows below the VA, to the jugular tubercle and the occipital condyle if it grows above, and toward both parts of the FM lateral wall, if it encircles the VA on both sides.

Dura opening

The most adequate dural incision is a curvilinear incision starting at the inferolateral corner then running vertically at a paramedian level (5 to 10 mm from the midline) and curving toward the superolateral corner. This type of incision permits to take the maximum benefit of the bone opening without contraincision and is generally easy to close. Keeping the dura over the neuraxis provides protection during the surgical dissection. Moreover, arachnoid connections between the dura and the medulla are left undissected to prevent an anterior fall of the neuraxis during tumor resection.

Intradural step

Lateral meningiomas are directly brought into view and their dural attachment directly accessible. Contrarily, anterior meningiomas are partially hidden by the neuraxis. The first step of the intradural stage, before beginning tumor resection, is to identify several important structures and to open the surgical access to the lesion by completely releasing the neuraxis. Important structures are the VA, the accessory nerve, and the dentate ligament. The VA is identified by following the course of the V3 segment where it pierces the dura matter. The first two digits of the dentate ligament have to be divided. To further improve the surgical access, the first cervical nerve root can be divided distal to its connections with the accessory nerve.

At this step, the surgical technique must be individualized according to the tumor location: above, below, or on both sides of the VA.

As previously mentioned, in cases of tumor developed below the VA, the lower cranial nerves are always pushed cranially and posteriorly by the tumor. These nerves will then be found at the superior pole of the lesion at the end of the surgery. The resection must start at the caudal aspect of the meningioma with the goal to release the dural attachment and to suppress the vascular supply first; then, the tumor is debulked in a dry surgical field with a sucker, an ultrasound aspirator, or a laser, according to the tumor consistency. When liberating the dural insertion, it is important to keep undetached a small part of the base, at the side of the neuraxis, to avoid free movement of the lesion, which can be responsible for inadvertent damage to the neuraxis during the remnant resection. When hollowing the tumor, a small layer is also kept with its capsule against the neuraxis. This part will be resected at the last surgical step and under better conditions when the meningioma is completely devascularized and the surgical field widely open.

If the tumor is developed above the VA, two special points must be taken into consideration: the displacement of the lower cranial nerves and the dissection of the VA branches. Indeed, in such location, the displacement of the lower cranial nerves cannot be anticipated. To prevent damage, the rootlets must be under control on the side of the jugular foramen and then followed along their courses more or less adherent to the meningioma. With the lesion being progressively debulked, the nerve rootlets can be more easily mobilized, often inferiorly, to allow a more confident tumor resection at some distance from fragile nervous structures. The tumor dissection from the VA branches, especially the PICA, is another difficulty encountered only with tumors developed above the VA. Precise knowledge of the patient anatomy based on preoperative investigation is mandatory.

If the meningioma encases the VA, the technique is identical as described above. Special consideration is nevertheless required if the meningioma has its insertion on the dura surrounding the VA penetration. The dural resection is better achieved by progressing from the extradural side toward the intradural aspect, along the VA because the VA invaginates into the dura with its periosteal sheath. This furrow can be resected as much as the VA adventitia is not invaded.

Dural closure

A watertight dural closure is required to prevent a postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage. The closure is generally easy with the curvilinear incision. If necessary, a dural patch using the suboccipital aponeurosis achieves a perfect closure. In any case, the muscular and aponeurosis layers must be tightly closed.

Antero-lateral approach

The antero-lateral approach is rarely used in our department as we consider that it is a good choice only in some meningiomas with extradural extension through the bony structures [15–17].

The antero-lateral approach to the craniocervical junction has been extensively described in the article focusing on the surgical exposure of the VA V3 segment and will not be detailed again for this reason [8]. Some points required nevertheless special consideration. The head has to be slightly extended with a rotation of 60° toward the opposite side. Because of this rotation, VA segments above and below the C1 posterior arch run parallel, separated by this bone. Opening the C1 transverse foramen is mandatory for VA transposition.

Bone opening

When completely liberated, the VA can be pulled out and transposed, bringing into view the FM lateral wall as the occipital condyle, the anterior and posterior arches of the atlas, the lateral mass of the atlas, and the C1–C2 joint become visible.

The exposure must now be adapted to each case, depending on the location and extension of the meningioma. The odontoid process can be reached by passing over the C1–C2 joint. The mastoid process can be resected and small bridging bone removed to open completely the jugular foramen from the end of the sigmoid sinus, to the jugular tubercle just underneath the junction with the jugular bulb, up to the beginning of the internal jugular vein.

Dura opening

The dural opening is most of the time out of concern because the antero-lateral approach is mainly indicated for extradural meningiomas. When lesions are developed in both extradural and intradural compartment, the dura is already opened by the lesion and must only be enlarged.

Dural closure

Dural closure can be a considerable problem in cases where the dural defect is anteriorly located at the level of the clivus, the anterior arch of the atlas, and the odontoid process.

Postoperative complications

The antero-lateral approach could induce a transient dysfunction of the accessory nerve by the nerve manipulation, responsible for pain along the trapezius muscle and weakness of the trapezius muscle and/or the SM muscle. During this approach, manipulation of the sympathetic chain could also be at the origin of a transient Horner’s syndrome.

VA damage has never been observed. In case of tumoral encasement, a balloon occlusion test must be realized.

Preservation of the lower CNs can be hazardous. If CN IX and X are damaged, postoperative swallowing problems must be anticipated.

Review of the literature

Published series

Yasargil has reviewed series published from 1924 to 1976 and counted 114 cases of FMMs. Since then, more than 400 cases of FMMs have been reported in the literature [2–7, 10, 18–22, 27, 35, 37, 38, 41, 44–46, 52, 54, 55, 57, 58]. George et al. [16, 19] reported on a series in the French literature of 106 craniocervical meningiomas from 21 hospitals. The largest single-center series have been published by Meier et al. [38] in 1984, Samii et al. [55] in 1996, and George et al. [18] in 1997. Table 1 summarizes published series over the last 20 years in the English literature.

Heterogenicity of published series

A heterogenous group of patients constituted the published studies. Several studies included not only FMMs but also other FM pathologies such as neurofibromas, schwannomas, as well as other various lesions leading result analysis precarious [2, 4, 10, 35, 38, 41, 45, 57, 58]. Table 1 summarizes also the high variability of tumor location, rate of VA encasement, rate of tumor recurrence, and surgical approaches. The proportion of anterior FMMs is comprised between 12.5 [2] and 100% [3, 27, 41]. The subdivision between anterior and lateral FMM is not always detailed in studies including 90 to 100% of antero-lateral FMMs [4, 6, 20, 21, 35, 44, 46, 54, 55, 57]. Posterior FMMs were always included in studies with anterior or antero-lateral lesions with a variable proportion from 2.5, 5, 9, 11, 28.5, 30, up to 50% [5, 7, 18, 37, 44, 55, 58]. The rate of VA encasement can be higher than 59% and the rate of tumor recurrence up to 80% [21, 57] (Table 1).

Surgical approaches, extent of bone resection, and need for fusion

FMMs are undoubtedly challenging tumors, requiring special considerations because of the vicinity of the brainstem, medulla oblongata, lower cranial nerves, and the VA. Several approaches have been advocated. The definite goals are to achieve the largest tumor removal and the lowest morbidity rate as possible. Minimizing the morbidity is obtained by choosing the appropriate exposure. The approach must allow adequate controls of important neurovascular structures, without exposing to unnecessary risks.

There is no discussion about the best surgical approach of posterior FMMs. The posterior approach is the best option, is well known by neurosurgeons, and is associated with a low morbidity rate.

The debate about the best surgical approach is more open for lateral and mainly anterior FMMs.

The transoral approach has been reported sporadically [10, 39]. Despite providing access to the anterior part of the craniocervical junction, this approach has several drawbacks in case of intradural lesions: increased risk of CSF fistula and meningitis after crossing of the contaminated oral cavity, poor access to laterally extending tumors resulting in a low rate of complete resection, and increased risk of posteroperative instability and velopalatine insufficiency [10, 39].

The two main surgical approaches reported in the literature are the far-lateral approach [28], also called postero-lateral approach or lateral suboccipital approach, and the extreme-lateral approach, also named antero-lateral approach. As detailed by Rhoton [51], the far-lateral approach is a lateral suboccipital approach directed behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the VA and just medial to the occipital and atlantal condyles and the atlanto-occipital joint. The extreme lateral approach is a direct lateral approach deep to the anterior part of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and behind the internal jugular vein along the front of the VA. In fact, both approaches permit drilling of the occipital condyle but provide a different exposure because of the differences in the approach direction.

The extreme-lateral transcondylar approach for FMMs was first reported by Sen and Sekhar [57] in 1990. Further publications of the same experienced skull base surgeons followed [4, 52, 54]. Salas et al. [54] reported in 1999 several variations of the extreme-lateral approach based on a series of 69 patients, including 24 meningiomas. The lesions were removed most of the time through a partial transcondylar approach and more rarely through transfacetal, retrocondylar, and extreme transjugular approaches. During the partial transcondylar approach, the posterior one third of occipital condyle and superior facet of C1 were drilled away. These authors also performed a partial mastoidectomy [4, 54, 57]. Arnautovic et al. [3] published their experience in 2000 on a series of 18 ventral FMMs. They used also the extreme-lateral transcondylar approach. The condyle drilling ranged approximately from one third to one half of the condyle, without causing craniocervical instability. The extreme-lateral trancondylar approach requires the VA transposition to reach and drill the occipital condyle [3, 4, 27, 45, 54, 57].

As others [5, 6, 20, 21, 27, 35, 41, 44, 55, 58], we advocate rather the postero-lateral approach, also called far-lateral approach, even for anterior intradural FMMs. During this approach, the VA is controlled in the horizontal portion of the V3 segment, above the C1 posterior arch. VA transposition is rarely performed and has only been reported in one series [46]. The extent of FM lateral wall drilling is variable, in fact directly proportional to the tumor extension to the contralateral side. In the literature, the occipital condyle resection varies between 0 and 66% [27, 41, 44, 46, 55]. In a recent publication, Bassiouni [5] classified judiciously surgical approaches in two groups: transcondylar or retrocondylar if the occipital condyle is not drilled. In our review of the literature (Table 1), we found nine series in which the retrocondylar approaches was used to reach anterior or anterolateral meningiomas [2, 5, 7, 21, 35, 37, 41, 55, 58]. In four of these series, a retrocondylar approach was not used in all cases but in 89.2, 82.5, 71.5, and 50% [21, 35, 37, 55]. The five other series are homogeneous and only included patients treated through a retrocondylar approach [2, 5, 7, 41, 58]. Of these, three studies reported complete resection in 100% of the cases [2, 41, 58]. In the two others, complete resection was noted in 90 and 96% of the cases, and the remaining lesions were resected subtotally [5, 7]. Surgical results were good, and surgical morbidity and mortality rates low [2, 5, 7, 41].

Extradural lesions can be treated either by posterolateral or anterolateral approach (Fig. 2). The extent of drilling during this procedure can be larger but is only dictated by the tumoral invasion and must be limited to the destroyed or invaded bone. In such a way, the question of instability is only a preoperative concern. In our experience of tumors located at the craniocervical junction, we have not observed any instability if less than half of the C0–C1 and C1–C2 joints were resected [15]. In our experience, VA transposition was merely performed in selected cases of FMMs with extradural extension and never for intradural lesions.

Surgical results

Morbidity–mortality–prognosis factors

In the Yasargyl’s review of the literature of series published before 1976, the overall mortality rate was approximately 13% but could be as high as 45% in some series [34].

Over the last 20 years, the overall mortality is 6.2%. The mortality rate is comprised between 0 and 25% (Table 1). Mortality rates higher than 10% were mainly observed in small series [4, 27, 37, 46, 57, 58].

In the Yasargil’s review, a good outcome was noted in 69% and a fair and poor outcome, respectively, in 8 and 10%. In series larger than ten patients published over the last 20 years (Table 1), neurological improvement, stability, and worsening were noted, respectively, in 70–100, 2.5–20, and 7.5–10% of the cases. The permanent morbidity rate is comprised between 0 and 60%. The permanent morbidity rate is lower through a far-lateral approach (0–17%), either transcondylar or retrocondylar, than through an extreme-lateral transcondylar approach (21%–56%, considering series without recurrent tumor). Lower cranial nerves dysfunctions are the most frequently encountered preoperative deficits. These deficits have the propensity to recover even completely postoperatively [3–5], except in cases of en plaque meningiomas or recurrent tumor [55].

Several factors lead the surgical procedure still more difficult, then influencing negatively the morbidity rate: anterior tumor location [18, 55], tumor size (smaller lesions are more difficult to resect because the surgical corridor is small), tumor invasiveness, extradural extension [18], VA encasement [22], absence of arachnoidal sheath [5, 14, 65], and adherences in recurrent lesions [4, 5, 55, 57].

Rate of tumoral resection

Based on a multicentric study from 21 hopitals, George et al. [19] reported 77, 16, and 7%, respectively, of complete, subtotal, and partial removals. Over the last 20 years, most of the studies reported complete or subtotal removal of the tumor [2, 4–7, 10, 18–22, 27, 35, 37, 41, 44–46, 52, 54, 57, 58]. Factors limiting the resection completeness are adherences of the lesion to vital structures, VA encasement and invasiveness of the lesion. Adherences are observed during repeated surgery and explain the lower rate of complete tumor resection (60–75% of Simpson grade 1) in surgical series in which a high rate of recurrent tumors are included [3, 55, 57]. Eventually, in recurrent tumors, some authors advocate leaving a small tumor remnant to preserve a low morbidity rate [5, 18]. On the other hand, Arnautovic et al. [3] favored radical removal of recurrent tumors with the goal of providing a relatively long and stable postoperative course, even at the price of frequent but transient morbidity induced by lower cranial nerves dysfunction. Arnautovic et al. [3] have also demonstrated that the rate of complete removal is higher at first surgery than when treating recurrence, advising then to be more aggressive at the first surgical presentation. VA encasement was noted in 38 to 59% in some series [5, 18, 21, 44, 55]. This factor was recognized as an independent factor of incomplete removal [55]. The location of the meningioma, either intraextradural or extradural, reflects the tumoral invasiveness. These tumors are less favorable to be completely resected than pure intradural lesions [19, 39]. In the French cooperative study [19], the rate of complete removal of intradural, extradural, and intraextradural meningiomas was, respectively, 83, 50, and 45%.

Our experience

Our experience has been published in 1997 after the treatment of 40 FMMs operated in the period 1980–1993 [18]. Twenty-four lesions were intradural, two were extradural, and four were intraextradural. Eighteen were considered anterior, 21 lateral, and one was posterior. The tumor was above the VA in four cases, below in 20 cases, and on both sides in 16 cases. The posterolateral approach was used in 31 cases, the anterolateral one in five cases, and the posterior midline in four cases. The rates of complete resection for intradural and extradural lesions were, respectively, 94 and 50%. Postoperatively, the clinical condition improves in 90% of patients, remains stable in 2.5%, and worsened in 7.5%. Our present experience over the last 25 years is now based on 97 FMMs (unpublished data). Complete removal was achieved in 86% and subtotal removal in 11%. Subtotal removals were due to extradural extension or to recurrent cases. The rate of complete removal increased up to 94% when selecting only intradural lesions treated at first presentation. We mainly use the far-lateral retrocondylar approach for intradural FMMs. In some cases, the drilling of the FM lateral wall has to be performed for intradural anterior meningiomas but remains limited at worst to the medial 20% of the FM lateral wall. Whatever, this extent of drilling has to be tailored according to the tumor characteristics. We consider nevertheless that more bone resection is never necessary because of the anatomical anterior position of the lateral mass of the atlas and the occipital condyle. Our attitude has been reinforced by cadaveric study, which has demonstrated that increasing the bone drilling is not associated with a significant widening of the surgical corridor [41]. In fact, resecting one third and one half of the occipital condyle increases the visibility respectively by 15.9 and 19.9°. Two anatomic reports have demonstrated that condyle resection allows a wider angle of exposure to gain the anterior foramen area [1, 59]. However, these studies did not consider the fact that in surgical approaches to anterior lesions, space-occupying lesions can enlarge the surgical corridor. We consider that the extreme-lateral approach could be associated with a higher morbidity rate than the far-lateral approach. The exposure allowed by the far-lateral retrocondylar or partial transcondylar approach is adequate for resecting even anterior intradural FMMs. The supposed benefit in term of exposure provided by the extreme transcondylar approach is counterbalanced by the risks associated with the CN XI dissection, the VA transposition, and the condyle drilling.

Conclusions

FMMs are challenging tumors in the vicinity of the brainstem, the VA, and lower cranial nerves. Several surgical approaches are possible, each one with specific indications. The drilling of the FM lateral wall required during the approaches is always limited and by itself should not be at the origin of any instability. Postoperative complications can be dramatic and must be anticipated.

References

Acikbas SC, Tuncer R, Demirez I, Rahat O, Kazan S, Sindel M, Saveren M (1997) The effect of condylectomy on extreme lateral transcondylar approach to the anterior foramen magnum. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 139:546–550

Akalan N, Seckin H, Kilic C, Ozgen T (1994) Benign extramedullary tumors in the foramen magnum region. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 96(4):284–289

Arnautovic KI, Al-Mefty O, Husain M (2000) Ventral foramen magnum meningiomas. J Neurosurg 92(Suppl 1):71–80

Babu RP, Sekhar LN, Wright DC (1994) Extreme lateral transcondylar approach: technical improvements and lessons learned. J Neurosurg 81:49–59

Bassiouni H, Ntoukas V, Asgari S, Sandalcioglu EI, Stolke D, Seifert V (2006) Foramen magnum meningiomas: clinical outcome after microsurgical resection via a posterolateral suboccipital retrocondylar approach. Neurosurgery 59:1177–1187

Bertalanffy H, Gilsbach JM, Mayfrank L, Klein HM, Kawase T, Seeger W (1996) Microsurgical management of ventral and ventrolateral foramen magnum meningiomas. Acta Neurochir Suppl 65:82–85

Boulton MR, Cusimano MD (2003) Foramen magnum meningiomas: concepts, classifications and nuances. Neurosurg Focus 14(6):e10

Bruneau M, Cornelius JF, George B (2006) Antero-lateral approach to the V3 segment of the vertebral artery. Neurosurgery 58(Suppl 1):ONS29–ONS35

Cohen L (1975) Tumors in the region of the foramen magnum. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW (eds) Handbook of clinical neurology. North Holland, Amsterdam, pp 719–729

Crockard HA, Sen CN (1991) The transoral approach for the management of intradural lesions at the craniocervical junction: review of 7 cases. Neurosurgery 28:88–98

de Oliveira E, Rhoton AL Jr, Peace DA (1985) Microsurgical anatomy of the region of the foramen magnum. Surg Neurol 24:293–352

Franckhauser H, Kamano S, Hanmura T, Amano K, Hatnaka H (1979) Abnormal origin of the PICA. Case report. J Neurosurg 514:569–571

George B (1991) Meningiomas of the foramen magnum. In: Schmidek HH (ed) Meningiomas and their surgical management. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 459–470

George B, Dematons C, Cophignon J (1988) Lateral approach to the anterior portion of the foramen magnum. Surg Neurol 29:484–490

George B, Lot G (1995) Anterolateral and posterolateral approaches to the foramen magnum: technical description and experience from 97 cases. Skull Base Surg 5:9–19

George B, Lot G (1995) Foramen magnum meningiomas. A review from personal experience of 37 cases and from a cooperative study of 106 cases. Neurosurg Quat 5:149–167

George B, Lot G (2000) Surgical approaches to the foramen magnum. In: Robertson JT, Coakham HB, Robertson JH (eds) Cranial base surgery. Churchill Livingstone, New York, pp 259–279

George B, Lot G, Boissonnet H (1997) Meningioma of the foramen magnum: a series of 40 cases. Surg Neurol 47:371–379

George B, Lot G, Velut S, Gelbert F, Mourier KL (1993) Tumors of the foramen magnum. Neurochirurgie 39:1–89

Gilsbach JM, Eggert HR, Seeger W (1987) The dorsolateral approach in ventrolateral craniospinal lesions. In: Voth D, von Goethe JW (eds) Diseases in the cranio-cervical junction. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, pp 359–364

Goel A, Nitta J, Kobayashi S (1997) Supracondylar infrajugular bulb keyhole approach to anterior medullary lesions. In: Kobayashi S, Goel A, Hongo K (eds) Neurosurgery of complex tumors and vascular lesions. Churchill Livingstone, New York, pp 201–203

Guidetti B, Spallone A (1988) Benign extramedullary tumors of the foramen magnum. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg 16:83–120

Hasegawa T, Kuboto T, Ito H, Yamamoto S (1983) Symptomatic duplication of the vertebral artery. Surg Neurol 20:244–248

Ibrahim AW, Satti MB, Ibrahim EM (1986) Extraspinal meningioma. Case report. J Neurosurg 64:328–330

Ingraham FD (1938) Intraspinal tumors in infancy and childhood. Am J Surg 39:342–376

Kowada M, Yamagushi K, Takahashi H (1972) Fenestration of the vertebral artery with review of 23 cases in Japan. Radiology 103:343–346

Kratimenos GP, Crockard HA (1993) The far lateral approach for ventrally placed foramen magnum and upper cervical spine tumours. Br J Neurosurg 7(2):129–140

Lanzino G, Paolini S, Spetzler RF (2005) Far-lateral approach to the craniocervical junction. Neurosurgery 57:367–371

Lasjaunias P, Guilbert-Tranier F, Braun JP (1981) The pharyngo-cerebellar artery or ascending pharyngeal artery origin of the PICA. J Neuroradiol 8:317–325

Lasjaunias P, Braun JP, Hassa AN, Moret J, Malnelfe C (1980) True and false fenestration of the vertebral artery. J Neuroradiol 7:157–166

Levy WJ, Bay J, Dohn D (1982) Spinal cord meningiomas. J Neurosurg 57:804–812

Levy C, Wassef M, George B, Popot B, Compere A, Tran Ba Huy P (1988) Meningiomes extra-crâniens. A propos de sept cas. Problemes pathogeniques, diagnostiques et therapeutiques [in French]. Ann Oto-laryngol 105:13–21

Lister JR, Rhoton AL Jr, Matsushima T, Peace DA (1982) Microsurgical anatomy of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. Neurosurgery 10:170–199

Love JG, Thelen EP, Dodge HW (1954) Tumors of the foramen magnum. J Int Coll Surg 22:1–17

Margalit NS, Lesser JB, Singer M, Sen C (2005) Lateral approach to anterolateral tumors at the foramen magnum: factors determining surgical procedure. Neurosurgery 56(Suppl 2):ONS324–ONS336

Margolis MT, Newton RH (1972) Borderlands of the normal and abnormal PICA. Acta Radiol (Diagn) 13:163–176

Marin Sanabria EA, Ehara K, Tamaki N (2002) Surgical experience with skull base approaches for foramen magnum meningioma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 42:472–480

Meier FB, Ebersold MJ, Reese DF (1984) Benign tumors of the foramen magnum. J Neurosurg 61:136–142

Miller E, Crockard HA (1987) Transoral transclival removal of anteriorly placed meningiomas at the foramen magnum. Neurosurgery 20:966–968

Mizukami M, Tomita T, Mine T, Mihara H (1972) By-pass anomaly of the vertebral artery associated with cerebral aneurysm and arteriovenous malformation. J Neurosurg 37:204–209

Nanda A, Vincent DA, Vannemreddy PSSV, Baskaya MK, Chanda A (2002) Far-lateral approach to intradural lesions of the foramen magnum without resection of the occipital condyle. J Neurosurg 96:302–309

Newton TH (1968) The anterior and posterior meningeal branches of the vertebral artery. Radiology 91:271–279

Newton TH, Mani RL (1974) The vertebral artery. In: Newton TH, Pons DG (eds) Radiology of the skull and brain, vol 2, book 2. C.V. Mosby, St. Louis, pp 1659–1709

Pamir MN, Kılıc T, Ozduman K, Ture U (2004) Experience of a single institution treating foramen magnum meningiomas. J Clin Neuroscience 11(8):863–867

Parlato C, Tessitore E, Schonauer C, Moraci A (2003) Management of benign craniovertebral junction tumors. Acta Neurochir 145:31–36

Pirotte B, David P, Noterman J, Brotchi J (1998) Lower clivus and foramen magnum anterolateral meningiomas: surgical strategy. Neurol Res 20:577–584

Radojevic S, Negovanovic B (1963) La gouttière et les anneaux osseux de l’artère vertébrale de l’atlas [in French]. Acta Anat 55:186–194

Rao TS, Sethi PK (1975) Persistent pro-atlantal artery with carotid vertebral anastomosis. Case report. J Neurosurg 43:499–501

Rhoton AL (2000) The cerebellopontine angle and posterior fossa cranial nerves by the retrosigmoid approach. Neurosurgery 47:S93–S129

Rhoton AL (2000) The foramen magnum. Neurosurgery 47:S155–S193

Rhoton AL (2000) The far-lateral approach and its transcondylar, supracondylar, and paracondylar extensions. Neurosurgery 47(3):S195–S209

Roberti F, Sekhar LN, Kalavakonda C, Wright DC (2001) Posterior fossa meningiomas: surgical experience in 161 cases. Surg Neurol 56:8–21

Rogers LA (1983) Acute subdural hematoma and death following lateral cervical spinal puncture. Case report. J Neurosurg 58:284–286

Salas E, Sekhar LN, Ziyal IM, Caputy AJ, Wright DC (1999) Variations of the extreme-lateral craniocervical approach: anatomical study and clinical analysis of 69 patients. J Neurosurg (Spine) 90(2):206–219

Samii M, Klekamp J, Carwalho G (1996) Surgical results for meningioma of the craniocervical junction. Neurosurgery 39:1086–1094

Sartor K, Fliedner E, Pfingst E (1977) Angiographic demonstration of cervical extradural meningioma. Neuroradiology 14:147–149

Sen CN, Sekhar LN (1990) An extreme lateral approach to intradural lesions of the cervical spine and foramen magnum. Neurosurgery 27:197–204

Sharma BS, Gupta SK, Khosla VK, Mathuriya SN, Khandelwal N, Pathak A, Tewari MK, Kak VK (1999) Midline and far lateral approaches to foramen magnum lesions. Neurol India 47:268–271

Spektor S, Anderson GJ, McMenomey SO, Horgan MA, Kellogg JX, Delashaw JB (2000) Quantitative description of the far-lateral transcondylar transtubercular approach to the foramen magnum and clivus. J Neurosurg 92:824–831

Stein BM, Leeds NE, Taveras JM, Pool JL (1963) Meningiomas of the foramen magnum. J Neurosurg 20:740–751

Tsuji N, Nishiura I, Kohama T (1986) Extradural multiple spinal meningioma: literature review and case report. Neurochirurgia 29:124–128

Wagle VG, Villemure J, Melanson D, Ethier R, Bertrand G, Feindel W (1987) Diagnostic potential of M.R. in cases of foramen magnum meningiomas. Neurosurgery 21:622–626

Wara WM, Sheline GE, Newman H, Townsend JJ, Boldrey EB (1975) Radiation therapy of meningiomas. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 123:453–458

Yasargil MG, Mortara RW, Curcic M (1980) Meningiomas of basal posterior fossa. In: Krayenbuhl U (ed) Advances and technical standards in neurosurgery, vol. 7. Springer, Berlin, pp 3–115

Yasargil MG, Mortara RW, Curcic M (1980) Meningiomas of basal posterior cranial fossa. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg 7:3–115

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Denis Rommel, M.D., for providing assistance in English corrections, and to Marie-Bernadette Jacqmain, for providing the medical illustrations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Comments

Allessandro Ducati, Torino, Italy

This excellent paper summarizes the wide experience accumulated over several years by the group of Bernard George, concerning a very difficult topic among the neurosurgical procedures, i.e. foramen magnum meningiomas (FMM). This subject has been treated in the literature several times, and there is debate (or confusion?) concerning the best approach and the best strategy to treat FMM (see for instance the very interesting summary on the topic by Rhoton and De Oliveira, in Surgery of the Craniovertebral Junction, Dickman et al. Eds., Thieme, 1998, pp. 13–57). One of the merits of this paper is its extreme lucidity and simplicity that reflect the familiarity of the authors with the problem of FMM. This work is easy to read, easy to remember, full of useful details, clear. Of great value is the accuracy of description of surgical anatomy: particularly the normal course and variation of the vertebral artery (VA), together with its spinal and meningeal branches, and the relationships among these and lower cranial nerves and dentate ligaments. Surgical planning and anticipation of possible dislocation of normal structures is another precious contribution. The description of surgical procedure step by step is exceptionally clear and helps to carry out the operation by any surgeon with a sufficient experience even not specific for this rare pathology. The classification is simple and based on facts that affect the surgical strategy. The idea that inspires the whole paper is that of achieving the maximal resection of FMM with maximal respect for all the structures, of course nerves and vessels, but also bone, in order not to cause postoperative instability. The Discussion is mainly centered on this point, and reaches convincing conclusions, based on the excellent results of the reported series. For surgeons who do not have the same experience and the same ability of Bernard George (and of course I am among them), maybe some opinions may appear a little bit too rigid, excellent in his hands but not necessarily in other’s. For instance: the sitting position used at the Lariboisière Hospital can be excellent in a short procedure of an expert, but may have more complications the longer it is; or the renounce to use intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring, especially useful when the nerve roots are intermingled with the tumour in FMM arising above the VA; or, finally, the choice not to transpose the VA routinely in the postero-lateral approach, that makes me anxious about a possible inadvertent lesion of the artery during surgery. Altogether, this is a great contribution to the neurosurgical culture, emphasizing the need for a very detailed anatomical knowledge, a thorough strategically planning and a careful surgical execution.

Volker Seifert, Frankfurt, Germany

This article is an excellent review of the surgical management of foramen magnum meningioma described by one of the most experienced skull base surgeons. In this paper Professor George details his experience and understanding of the different types of foramen magnum meningiomas. He classifies them based on their site of origin into anterior, lateral, and posterior foramen magnum meningiomas. He then details the different strategies and approaches to each type adding several tips based on his own personal experience. For the posteriorly located meningioma it is obvious that the posterior approach is enough. For those originating from the anterior aspect of the FM he favors the postero-lateral (far-lateral) approach and stresses the fact that the tumor itself, especially when large, it opens the corridor to the anterior aspect of the brainstem and upper spinal cord, to where an extreme lateral (transcondylar) approach is not necessary. While we agree with him that in a good number of cases this is true, the extreme lateral approach has its role and should not be a source of increased morbidity, as suggested by the authors, if the anatomic details of the region are well understood. What may challenge the exposure in this region is the complex venous plexus which could lead to cumbersome oozing that may hinder anatomic dissection. More recently we have been injecting Tiseal (fibrin glue) into the perivertebral venous plexus which controls venous oozing and this helped in performing an almost cadaver-like dissection.

Meningiomas continue to be surgical lesions. foramen magnum meningiomas in particular are not ideal for treatment with other modalities such as radiosurgery in view of the proximity of these tumors to the brainstem and the morbidity resulting from the persistent brainstem compression. As a result, this article, written by a very experienced skull-base neurosurgeon, provides valuable details and tips that can be used during surgical resection of foramen magnum meningiomas, and is an important addition to the neurosurgical literature.

Helmut Bertalanffy, Zürich, Switzerland

This article is a valuable overview dealing with the surgical anatomy and classification of foramen magnum meningiomas, describing the surgical technique and reviewing the pertinent literature to the subject. It presents the vast experience of the senior author (BG), accumulated over many years, and also reflected in previous publications. It is nicely shown that, when dealing with lesions of the foramen magnum, the vertebral artery is an anatomical structure of particular importance to the surgeon, as the artery may frequently be encased by tumor or present anatomical variations that must be respected during surgery. The technique used by Dr. Bernard George is well comprehensible and his method of subdividing the meningiomas according to their exact location and attachment should be a stimulus for others to adopt this classification system. On the other hand, the discussion on how much bone should be resected or not is somewhat overemphasized by the authors. Admittedly, the main criterion in this discussion should be the preserved function of the atlantooccipital joint, rendering a stabilization procedure unnecessary. As long as stability is preserved, however, bony resection can be varied according to the requirements of each specific case. My own experience comprises over 160 intradural lesions of the foramen magnum (meningiomas, aneurysms, ependymomas, hemangioblastomas, cavernomas, gliomas, neurinomas, metastatic carcinomas, epidermoid cysts, lipomas, AVMs and neurenteric cysts). While meningiomas or schwannomas may, indeed, significantly distort and displace the brainstem and spinal cord and thus reduce the necessity for extensive bony drilling, others do not alter the gross anatomy of the brainstem, as for instance small aneurysms or intraaxial cavernomas of the medulla. In such cases it is essential to first drill the posteromedial portion of the occipital condyle and part of the jugular tubercle in order to obtain an adequate view to the surgical target, or to allow control over the distal vertebral artery when temporary clipping is required. Such an exposure can only be achieved by a tailored but sufficient bony resection which I apply also in meningioma cases in order to first expose the dural attachment of the tumor. Overall, I have not encountered postoperative instability in any of these cases, even after extensive bony drilling. To conclude, we all can learn from this interesting article and the authors are to be commended for their instructive description and good results.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bruneau, M., George, B. Foramen magnum meningiomas: detailed surgical approaches and technical aspects at Lariboisière Hospital and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev 31, 19–33 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-007-0097-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-007-0097-1