Abstract

In this paper, we use an inductive approach and longitudinal analysis to explore political influences on the emergence and evolution of climate change adaptation policy and planning at national level, as well as the institutions within which it is embedded, for three countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia). Data collection involved quantitative and qualitative methods applied over a 6-year period from 2012 to 2017. This included a survey of 103 government staff (20 in Malawi, 29 in Tanzania and 54 in Zambia) and 242 interviews (106 in Malawi, 86 in Tanzania and 50 in Zambia) with a wide range of stakeholders, many of whom were interviewed multiple times over the study period, together with content analysis of relevant policy and programme documents. Whilst the climate adaptation agenda emerged in all three countries around 2007–2009, associated with multilateral funding initiatives, the rate and nature of progress has varied—until roughly 2015 when, for different reasons, momentum slowed. We find differences between the countries in terms of specifics of how they operated, but roles of two factors in common emerge in the evolution of the climate change adaptation agendas: national leadership and allied political priorities, and the role of additional funding provided by donors. These influences lead to changes in the policy and institutional frameworks for addressing climate change, as well as in the emphasis placed on climate change adaptation. By examining the different ways through which ideas, power and resources converge and by learning from the specific configurations in the country examples, we identify opportunities to address existing barriers to action and thus present implications that enable more effective adaptation planning in other countries. We show that more socially just and inclusive national climate adaptation planning requires a critical approach to understanding these configurations of power and politics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Addressing climate change requires appropriate plans and institutions to be put in place. The rapid development of climate change adaptation policies and plans globally is an encouraging trend (Nachmany et al. 2017) and has been supported by international policy frameworks of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Sustainable Development Goals, among others. A policy implementation gap with respect to climate change has received considerable attention (Biesbroek et al. 2013; Dupuis and Knoepfel 2013; Næss et al. 2015; Uittenbroek 2016), with the influence of politics often noted (e.g. Funder and Mweemba 2019; England et al. 2018a). Less focus has, however, been applied to the ways in which various politics—in terms of negotiation and contestation of power by state and non-state actors—affect the formation, evolution and agreement of policies upstream, including the institutional and governance structures in which they are embedded (Eriksen et al. 2015).

Differing political contexts mean that countries that experience similar climate change challenges might follow different pathways in the emergence and evolution of an agenda. We find this to be the case for Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia—neighbouring countries in the SADC region in sub-Saharan Africa ranked 156, 149 and 142, respectively (out of 181 countries), in ND-GAIN’s Global Adaptation Index—that combines vulnerability with readiness to respond to climate change (https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/). All three countries have experienced recent damaging major flood and drought events, and whilst there remains high uncertainty about changes in mean rainfall, variability is projected to increase, with higher frequency and intensity of extremes (Mittal et al. 2017; Conway et al. 2017; Davis-Reddy and Vincent 2017). Each country has frameworks in place to respond to climate change, but these differ in nature and scope reflecting each country’s political economy, which determines priorities and the allocation of resources. As governments change and new presidents assume power, the priority placed on climate change can shift, as well as the commitment to policies, programmes and an enabling institutional framework. The role of external influences, such as donors, is also key given the limited availability of domestic resources.

Drawing on multiple and often repeat in-depth interviews, a survey of government staff and content analysis of policy and programme documents, we take a longitudinal and inductive approach to surface the political factors that are associated with the emergence and evolution of climate adaptation policies—and the governance and institutional structures in which they are embedded—over approximately the last decade. “Political factors and their role in climate change adaptation in sub-Saharan Africa” provides a review of existing literature on the political economy of adaptation planning, and “Methodology” presents the methods applied in this study. “The emergence and evolution of national climate adaptation policy” gives an overview and historical contextualisation of the emergence and evolution of the climate change agenda in each country, covering policies, programmes and institutional context for addressing adaptation. Building on this, “Key political factors affecting the emergence and evolution of the national climate adaptation agenda in the three countries” then analyses two key elements of politics and power that emerge as important to the evolution of climate change agendas in the countries. “Discussion and conclusion” discusses the implications of these findings for adaptation planning and action in sub-Saharan Africa and concludes by arguing for the importance of analysing the upstream role of political factors in formal climate adaptation agendas to understand the drivers behind policy (in)action.

Political factors and their role in climate change adaptation in sub-Saharan Africa

Climate change policy does not arise in a political vacuum. It has to be integrated with existing political and organisational contexts, including within their “organisational routines” (Uittenbroek 2016). This does not happen independent of the operation of power, showing that climate change is a political issue (Nightingale 2017). Political economy, defined as “the processes by which ideas, power and resources are conceptualised, negotiated and implemented by different groups and different scales”, offers useful insights into the forces that shape climate policy (Tanner and Allouche 2011:1). Such an approach immediately places climate policy in the context of “long standing debates and struggles over resources between actors and institutions” (Næss et al. 2015: 543). It thus follows that an understanding of the underlying political and economic processes and their embedded histories helps to reveal causal mechanisms that may also shed light on entry points and opportunities for change (Næss et al. 2015; Sovacool et al. 2015).

Political economy studies of climate change have focused on the construction of narratives around climate change causes and consequences (Levy and Spicer 2013) and how these are then variously applied, for example, through the media (Boykoff and Yulsman 2013). Political economy marks a shift from an economic focus on material factors to one where the role of ideas and ideology in determining policy outcomes is recognised, through the application of power and resources (Tanner and Allouche 2011). In so doing, it acknowledges a role for bargaining between different actors (e.g. state and non-state) (Paterson and P-Laberge, 2018). In terms of outcomes, political economy analysis can also shed light on the shaping and allocation of risk and opportunity (Gotham 2016; Nightingale 2017; Mallin 2018). It provides insights into how and why trade-offs are made between competing goals, denoting which issues and groups emerge as winners or losers (Sovacool et al. 2015; Sovacool and Linnér 2015; Sovacool et al. 2017).

The hierarchical nature of implementing ministries in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia means that the highest levels of leadership, particularly the presidential level, are most influential on policy prioritisation (Pardoe et al. 2018a). Where institutional (and political) contexts allow, policy champions may also emerge at the ministry level to advance policy agendas. Such a process is, however, largely dependent on capacities of champions to exert their agency through a confluence of individual decision-making power and resource allocation privileges, both of which can be constrained by the wider political landscape (Funder et al. 2018; Habtezion et al. 2015) and organisational cultures and practices (Pardoe et al. 2018a).

The role of external influences has been a prominent feature of political economy analysis due to the framework provided by international policy processes (including negotiations and the promise of climate financing) on national climate change policy development and the different demands on developed and developing countries (Funder et al. 2018). A need to explore the changing nature of ideologies, power and resources under external (donor) influences at the national level has been noted, as they may exert important influences (Lockwood 2013; Næss et al. 2011; Tanner and Allouche 2011). Funder et al. (2018) and Pardoe et al. (2018a) found that donors may act as a positive force in providing additional resources to supplement domestic budgets, but that such support can divert and stretch staff resources, as donor recipients are required to fulfil reporting requirements and allocate staff as local contact points and facilitators.

Acknowledging the limited capacities of low-income countries and reflecting historical disadvantages, international financing has long been enshrined within the UNFCCC to support adaptation planning and is also explicit in the Paris Agreement (Bouwer and Aerts 2006; Biagini et al. 2014; Kinley 2017). Whether and how such funding effectively supports the design and implementation of adaptation policy and programmes partly depends on political economy in the receiving countries and the way in which ideas, power and resources are utilised (Tanner and Allouche 2011). This is also the case for international development assistance (Barnett 2008), much of which now mainstreams climate change in order to support adaptation (e.g. Klein et al. 2007; Ayers and Huq 2009). A growing body of literature is, however, critiquing the ways in which the exercise of power is reflected in adaptation financing, highlighting imbalances and inequity in targeting (Sovacool et al. 2017) and its role in the politics of vulnerability and adaptation among intended beneficiaries (Mikulewicz 2020). In particular, questions have already been raised regarding the potential inequitable application of adaptation finance (Barrett 2014; Persson and Remling 2014; Remling and Persson 2015).

Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia are, or have been, major overseas development assistance recipient countries, and in all three, the modalities of climate change funding (and much of the focus of our field work) are largely through pre-existing aid architecture and actors, particularly through bi- and multilateral processes. It is, thus, critical to consider attempts at policy influence and finance disbursement for adaptation in the context of wider debates on aid effectiveness and African states which have been the focus of several decades of attempts to incorporate or strengthen political/political economy analysis (Clark et al. 2005; Booth 2012; Yanguas and Hulme 2015).

To date, most political economy studies of climate change in developing countries have concentrated on in-depth studies of particular situations and countries. For example, Funder et al. (2018) examined resource control and state intervention in Zambia; Dodman and Mitlin (2015) looked at national to subnational processes in Zimbabwe; Tschakert et al. (2016) showed how micropolitics affects local level flood planning in India; and Nightingale (2017) showed how adaptation forms an arena in which multiple actors bargain for and contest power in Nepal. Research on the role of donors and external agents as actors in the process of adaptation policy design upstream is also a gap and one that is critically important to address in low-income country contexts.

We aim here to inductively research the sources and relative roles of internal and external power in the construction of the climate adaptation agendas in three sub-Saharan African countries—Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia-from its emergence in roughly 2007–2009. These southern African countries confront similar climate change risk, have experienced recent leadership change through presidential elections, and are all major recipients of donor assistance. By examining the emergence and evolution of climate adaptation policy over approximately the last decade, and the governance and institutional structures in which it is embedded, we identify the particular roles of two factors: national leadership and the role of international donors. This contributes to the political economy literature in two ways: firstly, by providing upstream analysis, compared with a focus on distributional outcomes (“winners” and “losers”) and implementation effectiveness, which of course are affected by the upstream situation; and secondly, by surfacing two political factors that are common across several countries—although the ways in which they manifest differ according to the context.

Methodology

The three case studies were selected as examples of low-income countries in sub-Saharan Africa where the research team had long-standing interactions related to adaptation research and practice, with each country facing similar climate change challenges that play out in different ways through their different political economies. Our theoretical starting point is recent literature on the importance of political economy factors as they relate to adaptation (e.g. Barnett 2008; Eriksen et al. 2015) and the need to bring further empirical data to this growing area of scholarship. Our specific aim is to elicit political factors affecting the emergence and evolution of national adaptation policy and the governance and institutional structures in which it is embedded. Our research design is inductive and exploratory (as often done in qualitative social science, e.g. Gisselquist 2014). Whilst the approach is similar to process tracing, which uses diagnostic evidence to provide the basis for both descriptive and causal inference and considers the unfolding of events over time (Collier 2011), it is not based on specific prior hypotheses or a formal analytical framework. As such, we do not include all the steps recommended in a checklist for process tracing, e.g. by Ricks and Liu (2018), rather we adopt an “ethnographic sensibility” that recognises the strengths of qualitative research in eliciting contextualised understandings of political processes (Simmons and Smith, 2017). Given this approach, our insights are associative not causal, and there is no claim to representativeness beyond the three cases—the inability to control for many confounding factors in local context precludes us from making any causal inference. Note that, whilst climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction show many complementarities and synergies, the fact that they are addressed by different policy and institutional frameworks means that we focus on the climate adaptation architecture here.

The case studies are presented with insights gained through an inductive process of multiple and often repeat in-depth semi-structured interviews with representatives from a variety of actors engaged in climate change, including ministries and government bodies (covering agriculture, water, energy, natural resources, environment, disaster risk management, etc.), multilateral and bilateral donors, civil society, private sector and academics and a once-off survey administered to government staff in implementing ministries. The samples for interviews and the survey involved purposive snowballing based on stakeholder analysis of the adaptation landscape in each country and further recommendations by interviewees. The survey enabled collection of quantitative data and simple open-ended questions, whilst semi-structured interviews allowed emergence and exploration of issues deemed important to the interviewees (Patton 1980). Policy analysis was also conducted over a 6-year period on relevant climate change policies, strategies and programmes (see England et al. 2018b) obtained through government sources and cross-referenced by interviewees.

In total, 242 interviews were conducted over a 6-year period, on multiple occasions between 2012 and 2017 (n = 106 in Malawi, n = 86 in Tanzania and n = 50 in Zambia) (Table 1) (see also Vincent et al. 2015; Nachmany 2018; Pardoe et al. 2018a, b; England et al. 2018b). Since the interviews were conducted over a long time period, it was possible for repeat interviews to take place, with some respondents being interviewed up to five times and a small proportion that had changed ministry. Interviews therefore allowed an examination of the evolution of the politics of climate change over time, reflecting the emergence of the national policy agenda around 2009 in all three countries, as well as perspectives on different sectoral viewpoints, rather than simply a snapshot. The interviews were structured broadly around issues relating to the national climate change agenda, with themes investigating: the processes through which climate policy has been developed and reasons for progress or stalling; the ways in which various interests have manifested; how ministries, donors and other groups work together or otherwise; how climate change is viewed and prioritised and the challenges for climate policy implementation.

The survey was administered to staff working at the national and local (district) levels of government, across a range of departments responsible for planning and implementing climate change adaptation strategies. The survey complemented the interviews with a focus on the institutional context of key implementing ministries, considering the workplace environment and capacities relating to adaptation. In total, 103 surveys were completed by respondents (n = 20 in Malawi, n = 29 in Tanzania, n = 54 in Zambia) from 2016 to 2017, with representation of all the sectors outlined in Table 1 (although often interviewees and survey respondents were different, with interviewees typically comprising higher level positions, e.g. directors and deputy directors, whilst the survey was targeted to technical staff). Following our purposeful snowball sampling, we had the opportunity to administer the survey at a workshop in Zambia where a large number of the target government staff were present, enabling us to obtain more returns there. Since responses are anonymous, it is not possible to determine the exact extent of overlap with interviewees. Surveys were only distributed to government staff; however, whereas a large proportion of interviewees are based outside of government and based on distribution of surveys, there is likely to be less than 10% overlap. The aims of the interviews and surveys were complementary rather than overlapping, so participation of a small number of individuals in both methods does not compromise the validity of findings.

Quantitative survey findings were stored and analysed in SPSS for simple descriptive statistics. The results of open-ended questions in the survey and transcripts of semi-structured interviews and the policy documents underwent a process of iterative and inductive content analysis to develop coding themes. The results presented in “The emergence and evolution of national climate adaptation policy” all arise from our inductive analysis of the qualitative findings, complemented with specific quotations and statistics of quantitative results. The interviews and survey findings are supplemented by an analysis of the trends in climate change policy development in each of the three countries. Dedicated climate change policies that originate from the responsible ministry were collected, analysed for content and placed on a timeline to assess those points at which the drafting process began to emerge and how this unfolded to the point of adoption, along with the institutions mandated to lead on climate change issues.

The emergence and evolution of national climate adaptation policy

In the three case studies, a range of institutional framings for climate change has developed and evolved, helping to contextualise and explain the present day situation. At the same time, all three countries have experienced sometimes multiple changes in political leadership since climate change began to be integrated into national policy discussions from around 2009, when the issue appeared on domestic agendas. Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia all produced National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs) prior to that, as mandated by the UNFCCC (Government of Malawi 2006; Government of Zambia, 2007; URT 2007). Any change in government can trigger sudden changes to policy priorities and shifts in the political economy, which bring new ideas to the fore, pushing others back or off the agenda and changing power relations and consequently financial and human resource allocations. In this section, we examine the evolution of climate change as a national policy issue, taking into account the adoption of policies, strategies and programmes and the institutional and governance landscape in which they are embedded. Tables 2, 3 and 4 outline timelines for Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia, respectively, that show major political milestones, ministries, key policy documents and programmes and other key events that have affected national adaptation planning.

Malawi

In Malawi, the housing of the climate change agenda and the political priorities accorded to it have changed over time (Table 2). The development of the institutional and policy environment to support climate change was initially supported by Malawi’s involvement in the JICA-funded Africa Adaptation Programme (2008–2012) (Malawi NGO representative). The programme undertook a number of studies to assess the most appropriate institutional framework and capacity and policy needs for climate change (Government of Malawi 2011a, b). It was institutionalised through the National Climate Change Programme (NCCP) and housed in the Department for Economic Planning and Development in the Ministry of Economic Planning and Development Cooperation. The NCCP aimed to create a National Climate Change Response Framework and Strategy to support national and local government institutions in delivering long-term climate-resilient and sustainable development. A National Steering Committee on Climate Change, comprising Principal Secretaries, was set up, supported by a National Technical Committee on Climate Change represented by government, academia and non-government technical staff (Malawi multilateral donor, government and NGO representatives).

The impetus created by the NCCP was a key driver behind the creation of a Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Management by Joyce Banda, who assumed the Presidency in 2012. The NCCP thus shifted to the Environmental Affairs Department within this ministry, which also acted as the focal point for the UNFCCC. Another department within the same ministry—the Department for Climate Change and Meteorological Services—is the country’s national meteorological agency and the primary supplier of forecasts and climate information.

In 2013, establishment of the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Management (MECCM) signalled high level commitment to addressing climate change (Malawi multilateral donor, government representatives). A National Climate Change and Environment Communication Strategy 2012–16 was released (Government of Malawi 2012). A National Climate Change Investment Plan 2013–18 was also developed and formally endorsed in 2013 (Government of Malawi 2013). This essentially proposes a Climate Change, Environment and Natural Resources Management Sector Wide Approach to direct donor funds for streamlined strategy implementation, with the ultimate aim of establishing a Climate Change Fund to strengthen channelling of both public and private climate finance. Climate change was also recognised in national planning documents, such as the Malawi Growth and Development Strategy II, 2011–2016 (Government of Malawi 2011c).

From 2012 to 2014, the MECCM was able to continue the momentum created by the NCCP and coordinated the drafting of a National Climate Change Management Policy, which was in advanced draft by the end of 2013. However, as soon as the 2014 presidential elections were called, the policy approval process was put on hold, resulting in the policy ultimately waiting until 2016 to be finally approved (Malawi multilateral donor, government and NGO representatives).

The new President elected in 2014 made the decision to restructure. The Environmental Affairs Department and Department of Climate Change and Meteorological Services became part of the Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and Mining. However, the senior management remained unchanged, enabling momentum to be continued with the approval of the policy in 2016 (Government of Malawi 2016). Subsequently, the focus has been on policy implementation and the development of a National Climate Change Strategy. When the third iteration of the Malawi Growth and Development Strategy 2017–22 was released, however, it did not contain the same emphasis on climate change, instead incorporating it in one of the six key areas, named “agriculture, water development and climate change management” (Government of Malawi 2017).

Tanzania

In Tanzania, climate change is located under the Vice President’s Office, within the Division of Environment (DoE). Since the publication of the NAPA in 2007, climate change has been increasingly mainstreamed into sectoral policies and plans (URT 2007; Pardoe et al. 2018b). Those dedicated national policies and strategies on climate change from the Division of Environment were, however, only published in 2012 (Table 3). These consist of the National Climate Change Strategy (URT 2012a), the National Climate Change Communication Strategy (URT 2012b) and Guidelines for Integrating Climate Change Adaptation into National Sectoral Policies (URT 2012c). Since 2012, there have been no further climate change strategies or plans published by the DoE, and critically, Tanzania still lacks a dedicated climate change policy (Smucker et al. 2015). However, a review and revision of the National Environment Policy, published in 1997, was underway at the time of interviews in 2017 (Tanzania government agency representative). The revised policy is expected to include references to climate change and adaptation, which were not mentioned in the 1997 version (Maro 2008). It is unclear to what extent climate change will feature in the policy, as compared with other environmental concerns, due to considerable uncertainty over the national position on climate change, since elections in 2015 (Tanzania NGO representative).

Climate change has been located under the DoE since it was first recognised at the national level—but the DoE is not recognised as a particularly powerful department (Tanzania NGO and donor representatives). Indeed, the DoE tends to avoid a proactive approach to promote the integration of climate change in sectoral policy and planning (Tanzania government agency representative). Instead, sectors that have been more proactive have tended to do so with donor support, based on a recognition of the importance of the issue for the sector (Tanzania government agency and donor representatives; URT 2018; MAFC 2014). Addressing climate change at the department and ministry level tends to be undertaken in a fairly ad hoc manner, as opposed to forming part of a wider nationally coordinated effort (Tanzania NGO and donor representatives).

Zambia

Climate change arose as a domestic political issue in Zambia in 2009, when UNDP, with the support of the government of Norway, established a Climate Change Facilitation Unit (CCFU) in the Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Natural Resources (Zambia government representative)(Table 4). The CCFU was staffed by government and external experts, whose role included leadership of development of a National Climate Change Communications and Advocacy Strategy and National Climate Change Response Strategy (NCCRS) and initial steps in drafting a policy (Republic of Zambia 2011a, b). Following a presidential election in 2011, two ministerial reshuffles in quick succession saw the institutional home for the CCFU shift twice, to ultimately reside in the Ministry of Lands, Natural Resources and Environmental Protection (Zambia government and NGO representatives).

As part of the policy development process, the NCCRS recommended establishment of a National Climate Change Development Council. Structural arrangements to accommodate this were discussed by sectors considered vulnerable by the NAPA and the NCCRS (Republic of Zambia 2007, 2011b). Discussions were not resolved at the start of a large project-the Pilot Programme for Climate Resilience (PPCR), which required a secretariat to oversee its activities. Thus, with the CCFU’s mandate essentially complete, it was subsumed in 2012-2013 into an Interim Climate Change Secretariat (ICCS). The intention was that this would eventually form the basis of the council which, in turn, would be responsible for overseeing the implementation of the policy (Zambia government and NGO representatives). Following some debate, the council placed the ICCS under the Ministry of Finance.

The ICCS was mandated to coordinate climate change activities across government, including programmes funded by external parties, and to act as the implementing secretariat for the PPCR. The timing was serendipitous, as the PPCR contributed to the administrative and fiduciary costs during the setting-up and the running of the ICCS, enabling the momentum achieved during CCFU to be maintained (Zambia government representative). From 2012 to 2017, ICCS successfully coordinated a number of major climate change projects in country, funded by major multilateral and bilateral donors.

The establishment of ICCS added complexity to the institutional landscape of addressing climate change in Zambia, since it brought on board an additional ministry (its parent ministry, the Ministry of Finance). The Ministry of Lands, Natural Resources and Environmental Protection retained the function of focal point to both the IPCC and UNFCCC. The interest of the Ministry of Finance in being involved in climate change issues was cemented in August 2014, when it was nominated to be the country’s National Designated Authority to the Green Climate Fund.

Following the 2016 presidential election, an additional cabinet reshuffle added further complications, when both ministries involved in climate change were split. The Ministry of Finance was split into the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of National Development Planning, the latter of which eventually integrated the ICCS. The Ministry of Lands, Natural Resources and Environmental Protection was split into the Ministry of Water Development, Sanitation and Environmental Protection (which included the UNFCCC focal point) and the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources (where the Department of Climate Change is situated). Among confused steering committee arrangements, a hastily assembled task force was tasked with finalisation of the National Climate Change Policy, which was achieved towards the end of 2016. The task force process overlooked the stakeholder-agreed structure and operationalisation of the policy, however, as had been originally envisaged in the NCCRS. With the policy approval, the ICCS ceased to exist—but until now, decisions on next steps have reached an effective stalemate, with three ministries all laying claim to the issue (Zambia government representatives).

Key political factors affecting the emergence and evolution of the national climate adaptation agenda in the three countries

Two main political themes that arose inductively from the data analysis as important in the emergence and evolution of the climate adaptation agenda are the role of national leadership and the role of international donors. Comparing and contrasting the three case studies shows that both factors are important, but in different ways, and the interactions between those factors determine the way in which climate change is addressed over time and highlight opportunities for broader learning.

The role of national leadership

In all three countries, the current climate policies and plans have been developed under preceding governments. The analysis of policy and repeat interviews over the course of several years has shown how leadership transition at the highest level brings changes to policy priorities, which can mean that climate change either rises up or falls off the agenda. In Malawi, for example, momentum picked up under Bingu Wa Mutharika’s leadership and was consolidated under the leadership of Joyce Banda, whose new ministerial structure signalled the high level commitment to addressing the issue. Such commitment was then evidenced in the adoption of a number of policies, strategies and plans relating to climate change. After his election in 2014, Arthur Peter Mutharika reduced his cabinet to 18, leading to a restructure in which the Environmental Affairs Department and Department of Climate Change and Meteorological Services became part of the Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and Mining. The next iteration of the Malawi Growth and Development Strategy 2017–2022 also contains a lesser emphasis on climate change.

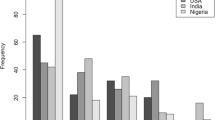

Such a lesser emphasis may explain why fewer than 20% of survey respondents (surveyed after the election) expected positive changes from the government in addressing climate change or expected an emphasis in climate change and why even fewer (15%) agreed that the new government would emphasise climate change (Fig. 1). The key role of political leadership in driving policy agendas was expressed by an interviewee from a multilateral donor in Malawi, who highlighted that Arthur Peter Mutharika’s Vice President, Saulos Chilima, wanted to reverse the trend of economic growth being linked to disasters and has been a champion for disaster risk reduction. Another interviewee from a different multilateral donor in Malawi highlighted that “there is a need to mobilise key players in politics to make progress”.

Interview respondents in Tanzania also highlighted the importance of high level political leadership in pushing agendas. A Tanzanian donor representative commented that “it’s clearly the leadership of the President, if he would speak out on climate change or tell his government ‘This is a priority. We have to consider climate change and everything because otherwise we can’t achieve our development targets’, I think that’s the thing that would make an immediate difference”. They noted the relative invisibility of climate change for President John Magufuli, however, citing the fact that he had not yet mentioned climate change; “we have not yet heard the President talk about climate change” (Tanzania NGO representative) and “I think the top is political leadership from the very highest level, but I understand the President isn’t ever thinking about climate change” (Tanzania donor representative), making it difficult to determine his stance on the issue. Instead, since election, the Presidency has prioritised domestic economic growth through emphasis on industrialisation, as outlined in various 5-year plans (URT 2011, 2016). At the same time, the President has limited his own international travel—thus, whilst representatives are sent to the UNFCCC Conferences of Parties, the President’s limited engagement in international policy processes and dialogues has led to very little effort to address climate change at the national level (Nachmany 2018; Pardoe et al. 2018b).

Survey results showed that whilst respondents in Tanzania overwhelmingly agreed (79%) that they expected positive changes from the change in government, this did not translate into a positive change in attention towards climate change. Less than a quarter (24%) of respondents agreed that the recent change in government will emphasise climate change (Fig. 1). Such a finding was confirmed in several interviews where respondents suggested that, although climate change is increasingly recognised as a physical phenomenon, it is not necessarily seen as a priority issue for the government and key ministries compared with other pressing issues: “you won’t see it in the manifestos. It’s kind of an invisible issue [but] there is recognition that climate change is serious and real” (Tanzania NGO representative) and that “climate change is one [issue] but in terms of priority, the government is focussing on development” (Tanzania government agency representative). A donor representative commented that “There have been many changes in issues like the past administration, Kikwete was very much into climate change issues … The current President hardly talks about climate change.”

Shifts in policy ambitions and priorities are common in times of change in president, and the survey results highlight how the combination of changes in leadership and the influence of leadership priorities on budgets leads to a very short-term focus in planning. Our longitudinal study has highlighted how policies developed under one leader may stall when a new leader arrives, with new ideas and ideologies that affect the way that climate change is viewed and resourced. In a pattern that was uniform across the three countries, respondents highlighted that they focus their planning on a 1–5-year timeframe, with an average of 76% of survey respondents across the three countries saying that their planning is frequently focused on this timeframe, approximately one-fifth planning for 5–10 years, and very few mentioning longer timeframes (Fig. 2). This was echoed in interviews with comments in all countries such as “we plan based on the person’s election. After being elected, you stay there for five years, everyone is thinking around the vicinity of five years. Most people don’t want to think beyond five years for political reasons” (Tanzania government representative). Changes in political leadership are also typically accompanied by cabinet reshuffles, changes in ministry mandates and, frequently, rotation of high level civil servants that are often political appointees (Malawi NGO and donor representatives). Such institutional rearrangements create grey areas around operational mandates and impede implementation and project management (Malawi multilateral donor representative).

The implications of this short-term focus have particular implications for climate change, as climate change adaptation requires longer term thinking—yet this is incompatible with political election cycles. Regular changes in leadership can lead to sudden changes in the emphasis on climate change. This may sometimes strengthen attention to climate change (e.g. in the case of Zambia), whereas, on other occasions, it may herald a shift away from climate change (e.g. Tanzania). In Malawi, representatives of multilateral and bilateral donors and government highlighted that people want short-term benefits and returns that are rapidly visible, which is why issues such as agriculture and disaster management are often prioritised over climate change—with one stating “short-term, fragmented approaches provide political gains”. In fact, one government department representative even suggested that a 5-year timeframe is too long for planning, commenting on the 5-year plan that “it is just like a bible, we read it and put it over there” (i.e. even 5 years is too long considering the timeframe on which they operate).

These sentiments were reflected in an open-ended question on the survey, which asked what would make staff more confident in integrating climate information for planning. Survey responses often highlighted challenges with unreliable budget allocations and disbursements associated with changing political priorities: In Malawi, many interviewees spoke of the inertia and incrementalism in government and the “resistance to change” among bureaucrats (bilateral donor representative). In alignment with this, a multilateral donor stated that “when government fails to lead, donors often step in—yet government will frequently not integrate their efforts”.

The role of donors

Donor funding and the role of external actors have played a range of (generally) proactive roles in the evolution of the climate change agenda in each country. Despite increasing numbers of initiatives to track adaptation finance and the use of climate markers in aid flows, robust information on the receipt of donor funding to specific developing countries is scarce (Donner et al. 2011; Buchner et al. 2011). A 2012 analysis found that Norway, the FAO, the World Bank, USAID and the European Union were among the major contributors to adaptation activities in Malawi (CCAPS 2013). In all three countries, donor support played a key role in the emergence of the climate change agenda and supported the development of policies and strategies. Malawi and Tanzania were part of the JICA-funded Africa Adaptation Programme, for example, which ran from 2008 to 2012; and in Zambia, climate change emerged as a domestic political issue in 2009 when UNDP, with the support of the Government of Norway, established the CCFU in the Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Natural Resources.

In Zambia, the receipt of substantial donor funding for climate change has created incentives for bargaining and contestation around control of the climate change agenda at ministerial level. Zambia was selected to receive funds from the PPCR, under the Climate Investment Funds, in 2011. Numerous interviewees inside and outside the government commented on the serendipitous timing of this, coinciding with the finalisation of the National Climate Change Response Strategy that mandated creation of a National Climate Change Council. Structural arrangements to accommodate this were discussed by sectors considered vulnerable to climate change by the NAPA and the NCCRS. The institutional issue around which ministry would hold the climate change portfolio was, however, described as a “hot potato” by both a multilateral donor and a government staff member. The imminent arrival of the PPCR, which required a secretariat to oversee its activities, as mentioned earlier, catalysed the decision to form an Interim Climate Change Secretariat (ICCS).

In effect, the formation of the ICCS in Zambia postponed a final decision on the permanent institutional setup to address climate change. However, continued receipt of international climate finance (PPCR alone contributed $91 million to the country as of 2019)—and the promise of additional funds through mechanisms such as the Green Climate Fund—essentially provided a powerful incentive for ongoing interest in the climate change agenda. At the same time, the backdrop of regular cabinet reshuffles that have accompanied a period of unusually rapid presidential change in Zambia further complicated the decision on a long-term institutional home. Three ministries currently all lay claim to the climate change agenda, and a final institutional home is yet to be confirmed. However, the task force process overlooked the stakeholder-agreed structure and operationalisation of the policy, as had been originally envisaged in the NCCRS. With the policy approval, the ICCS ceased to exist, but as yet, decisions on next steps have reached an effective stalemate with three ministries, as outlined in the section “Zambia”, all laying claim to the issue. With such institutional complexity and overlapping processes and lack of clarity with regard to mandate, it is not surprising that over 35% of survey respondents in Zambia said that policy is rarely implemented—the second highest after Tanzania (Fig. 1).

Whilst the availability of resources has not caused the levels of contestation and bargaining around climate change evident in Zambia, in Malawi and in Tanzania, smaller scale donor-supported projects and funding opportunities can facilitate/enable projects where domestic budget allocations are otherwise limited. In terms of power, ideas and ideologies, as seen in the case of Zambia, the availability of funding opportunities may lead to turf wars between ministries and departments.

Implementation of policy is also adversely affected by the high levels of uncertainty that stem from reliance on donor funding rather than predictable, on-budget resource allocation. Reliance on donors, as mentioned earlier, can also create competition between ministries, as they bargain for resources with which to work. In Malawi, representatives of several ministries bemoaned the fact that one department was acting as an implementer for several donor-funded climate adaptation programmes, despite having only a coordination mandate. Competition for resources has another effect that further impedes policy implementation—it creates barriers to coordination and impedes the coherent cross-sectoral approaches that are necessary to effectively adapt to climate change (England et al. 2018b). One NGO representative in Malawi highlighted how coordination is impeded “because everyone wants their names on things”, whilst a former government and bilateral donor representative stated that “the problem with climate change is there are a good number of players and organisers that mean well-but coordination is a problem”. A Malawi government representative further explained how they could not merge two coordination fora, as they would have liked, due to donor reporting requirements. However, as the section “Tanzania” shows, the President currently promotes a focus on self-reliance and has moved away from courting donor support and promoting issues of wider international concern, including climate change: “So now we have a much more inward-looking, nationalistic type of presidency. The previous one was much more outward-looking…the administration’s changed.” (Tanzania NGO representative).

Although there were some examples of policy champions within the government, the often rapid rotation of permanent secretaries and directors can impede their ability to drive progress. A government representative in Malawi explained how these factors combine to create reluctance to plan into the future, due to the uncertainty of resources being available due to dependence on donors. He noted that his department’s main plan “has a list of infrastructure schemes to develop and a budget of anticipated costs…so development partners will then shop from the list”. A government ministry representative in Tanzania highlighted that “climate change for us is not a priority since we have other issues.” However, “they [donors] are trying to have an influence on us [through] funds … to develop proposals on different basins we are working on so that we can deal with climate change”. Another multilateral donor in Malawi observed that a certain government department “dances to the tune of [another donor]”. The consequence for government technocrats of being reliant on uncertain donor funding is that it may undermine a sense of staff autonomy and agency to act, as the funding is linked primarily to the goals of the funder, rather than the government agencies (Pardoe et al. 2018a). In addition, in Zambia, a government representative highlighted the burdens placed on scarce human resources for meeting the varying reporting requirements of different donors who funded different projects being implemented. This raises questions as to whether donors are influencing and/or subverting national interests, providing funds for activities that support donor demands (themselves often linked to the political leadership in their own countries) rather than supporting national policies.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we applied purposive sampling of government and non-government stakeholders in the climate policy arena and complementary data from a survey and interviews and document analysis to conduct a longitudinal analysis of the political influences on the evolution of the national climate adaptation agenda in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia. Based on these data sources, our findings highlight two main factors that are common across all three countries but show that the ways in which they have operated and interacted in each country have led to three different trajectories of policy evolution. These two political factors are the roles of national leadership and donors. Together, the intersection of national leadership and donors over time is associated with the priority placed on, and resources dedicated to, climate change, through policies and programmes and the institutional framework through which they are managed. As we have shown, this varies in each country. In Malawi, the evolution of the national climate change agenda, as manifest in policies, programmes and institutions, is very closely linked to power exercised through political leadership. In Zambia, the high flux in the ministerial environment for climate change reflects the turf wars and battles which are less directly and immediately connected to changes in power compared with Malawi—yet they do show a high degree of change in responsibilities. In Tanzania, the relative stagnation in the climate change policy landscape since around 2015 reflects a lessening of political interest in climate change as an international issue rather than one of high domestic relevance. Given our methods, these insights are associative not causal, and we caution against transferability of findings beyond the three cases—similar methods would have to be applied in other countries to allow comparative analysis.

Identification of the importance of donors in shaping national climate change agendas has implications for aid effectiveness and development goals. Broader scholarship on political processes in aid effectiveness notes the general diplomatic assumption that recipient countries have leaders for whom national development is a central objective (Booth 2012). However, Booth argues that in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, ‘the modal pattern is that public policies are largely driven by short-run political considerations, and these usually dictate a clientelistic mode of political legitimation, not one based on delivery of the public goods required for economic and social transformation’ (Booth 2012: 540). Some aspects of our findings echo these concerns, and they are highly relevant for climate change as a popular policy agenda and increasing source of finance being channelled through overseas development aid mechanisms, as is increasingly the case. Calls for opening up rather than closing down opportunities for contestation (Eriksen et al. 2015) and a more transformative agenda for adaptation (Kates et al. 2012; Pelling et al. 2015) recognise the importance of power structures and need for political analysis. However, these aims are constrained by the nature of the aid bureaucracy delivery system itself, which has shown limited progress towards integrating political analysis into its practice (Yanguas and Hulme 2015). Measures to address such concerns mesh well between those identified by adaptation and broader development scholars. In terms of political leadership, Booth (2012) stresses the need for political incentives to align such that leaders are motivated by longer term national development goals. This requires political economy analysis that reveals power structures working against positive change based on deep understanding of actors and interests at play (Barnett 2008; Tanner and Allouche 2011; Booth 2012; Eriksen et al. 2015).

What this research has shown, contributing to the gap highlighted by Tanner and Allouche (2011), is that donors can (but do not always) significantly influence power and ideologies by providing resources in terms of financial but also technical support. In this way, resources can (and frequently do) incentivise attention to climate change—but this takes place through different mechanisms, depending on the stance of the leadership/president on the importance of climate change in the national agenda.

Whilst power brings resources, however, resources may also bring power, and the influence of donors is not always benevolent. This is particularly the case in developing countries, where scarce national resources often result in a de facto surrender of power to those that provide the financial resources. As demonstrated in Zambia, external resources may promulgate turf wars and battles to secure responsibility for the climate change agenda in order to secure access to a funding stream. In Malawi, whilst it has not manifested in the institutional and governance arrangements to the same extent, intense competition for scarce resources has similarly created obstacles to the cooperation and coherence required to address a cross-sectoral issue such as climate change adaptation. Even in Tanzania, where donor influence is diminishing, it still influences departments and diverts resources. Over the course of time and particularly with changes in leadership and resulting restructuring of ministries, this has resulted in waxing and waning commitments to the climate change agenda, accompanied by complex and often contested arrangements, where responsibilities are split over different departments—resulting in confusion around mandates and ultimately hampering effectiveness in planning and implementation.

This study shows convergence of power and resources—not only from the perspectives of donors, who resemble resource holders and so bring power, but also from the political leadership. The presidents are primarily the source of power in all three countries, but they also determine the extent to which, and way in which, donor resources are “allowed” to enter the landscape. In Tanzania, for example, a more hostile environment is developing that restricts the influence of donor funding—whereas in Zambia, sanctioned and sought after funds themselves have led to contested territory. The interaction between power and resources (and the power embedded within the resources) creates a different—and arguably more complex—political economy landscape for climate adaptation in sub-Saharan Africa, relative to the global North. As such, unravelling the roles and interaction between such influences is challenging and dependent on the manner in which external donors are allowed entry (or not) to the national political landscape.

In this paper, we have focused on national level adaptation planning—but the politics at this level have broader implications. An understanding of political economy and power could identify the areas where power and resources converge and where they do not, allowing targeting of those currently losing out on support for adaptation (e.g. Barrett 2014; Persson and Remling 2014; Remling and Persson 2015). The framing and construction of societal issues such as climate change reflects particular ontologies which are embedded in power relations (Goldman et al. 2018). Since the aim of national level adaptation planning is for subnational level implementation, the way in which adaptation is constructed and embodied, and the power relations that it reflects, can have distributional effects on who benefits and who loses from this construction (Nightingale et al. 2019). Thus, developing socially just and inclusive national adaptation planning—as a prerequisite for implementation—also requires a critical approach to understanding these configurations of power and politics.

References

Ayers JM, Huq S (2009) Supporting adaptation to climate change: what role for official development assistance? Development Policy Review 27(6):675–692. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2009.00465.x

Barnett J (2008) The effect of aid on capacity to adapt to climate change: insights from Niue. Political Science 60(1):31–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/003231870806000104

Barrett S (2014) Subnational climate justice? Adaptation finance distribution and climate vulnerability. World Development 58:130–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.014

Biagini B, Bierbaum R, Stults M, Dobardzic S, McNeeley SM (2014) A typology of adaptation actions: a global look at climate adaptation actions financed through the Global Environment Facility. Glob Environ Chang 25:97–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.01.003

Biesbroek GR, Klostermann JEM, Termeer CJAM, Kabat P (2013) On the nature of barriers to climate change adaptation. Reg Environ Chang 13:1119–1129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0421-y

Booth D (2012) Aid effectiveness: bringing country ownership (and politics) back in, conflict, security & development, 12(5), 537–558, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2012.744184

Bouwer JM, Aerts JCJH (2006) Financing climate change adaptation. Disasters 30(1):49–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.2006.00306.x

Boykoff MT, Yulsman T (2013) Political economy, media, and climate change: sinews of modern life. WIREs Climate Change 4(5):359–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.233

Buchner B, Brown J, Corfee-Morlot J (2011) Monitoring and tracking long-term finance to support climate action, OECD Publishing, Paris, paper no. 2011(3)

CCAPS (2013) Tracking climate aid in Africa: the case of Malawi, climate change and African political security research brief 18, Robert S. Strauss Center for International Security and law, University of Texas at Austin

Clark GC, Andersson K, Ostrom E, Shivakumar S (2005) The Samaritan’s dilemma: the political economy of development aid. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Collier D (2011) Understanding process tracing. PS: Political Science & Politics 44(4):823–830. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096511001429

Conway D, Mittal N, Archer van Garderen E, Pardoe J, Todd M, Vincent K, Washington R (2017) Future climate projections for Tanzania. Future climate for Africa country climate brief, 12p. http://www.futureclimateafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/fcfa_tanzania_climatebrief_web.pdf

Davis-Reddy CL, Vincent K (2017) Climate risk and vulnerability: a handbook for southern Africa (2nd edition). CSIR, Pretoria, 202. https://www.csir.co.za/documents/sadc-handbooksecond-editionfull-reportpdf

Dodman D, Mitlin D (2015) The national and local politics of climate change adaptation in Zimbabwe. Clim Dev 7(3):223–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2014.934777

Donner SD, Kandlikar M, Zerriffi H (2011) Preparing to manage climate change financing. Science 334:908–909. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1211886

Dupuis J, Knoepfel P (2013) The adaptation policy paradox: the implementation deficit of policies framed as climate change adaptation. Ecol Soc 18(4):31. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05965-180431

Eisenack K, Moser SC, Hoffmann E, Klein RJT, Oberlack C et al. (2014) Explaining and overcoming barriers to climate change adaptation. Nat Clim Chang 4:867–872. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2350

England MI, Stringer LC, Dougill AJ, Afionis S (2018a) How do sectoral policies support climate compatible development? An empirical analysis focusing on southern Africa. Environmental Science and Policy 79:9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.10.009

England MI, Dougill AJ, Stringer LC, Vincent KE, Pardoe J et al. (2018b) Climate change adaptation and cross-sectoral policy coherence in southern Africa. Reg Environ Chang 18(7):2059–2071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-018-1283-0

Eriksen SH, Nightingale AJ, Eakin H (2015) Reframing adaptation: the political nature of climate change adaptation. Glob Environ Chang 35:523–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.09.014

Funder M, Mweemba CE (2019) Interface bureaucrats and the everyday remaking of climate interventions: evidence from climate change adaptation in Zambia. Glob Environ Chang 55:130–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.02.007

Funder M, Mweemba C, Nyambe I (2018) The politics of climate change adaptation in development: authority, resource control and state intervention in rural Zambia. J Dev Stud 54(1):30–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2016.1277021

Gisselquist RM (2014) Paired comparison and theory development: considerations for case selection. PS: Political Science & Politics 47(2):477–484. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096514000419

Goldman MJ, Turner M, Daly M (2018) A critical political ecology of human dimensions of climate change: epistemology, ontology, and ethics. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Chang 9(4):e526. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.526

Gotham KF (2016) Coastal Restoration as Contested Terrain: Climate Change and the Political Economy of Risk Reduction in Louisiana. Sociological Forum 31:787–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12273

Government of Malawi (2006) Malawi’s national adaptation programmes of action (NAPA) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Government of Malawi, Lilongwe

Government of Malawi (2011a) Sector policies response to climate change in Malawi: a comprehensive gap analysis. Government of Malawi, Lilongwe

Government of Malawi (2011b). Training needs assessment for climate change management structures in Malawi. National Climate Change Programme Ministry of Finance and Development Planning. http://www.nccpmw.org/

Government of Malawi (2011c) Malawi growth and development strategy II, 2011–16. Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, Lilongwe

Government of Malawi (2012) National Environment and Climate Change Communication Strategy 2012-16, Ministry of Environment and Climate Change. Management, Lilongwe

Government of Malawi (2013) National Climate Change Investment Plan 2013–18, Ministry of Environment and Climate Change. Management, Lilongwe

Government of Malawi (2016) National Climate Change Management Policy. Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy and Mining, Lilongwe

Government of Malawi (2017) Malawi Growth and Development Strategy III, 2017-22. Government of Malawi, Lilongwe

Habtezion S, Adelekan I, Aiyede E, Biermann F, Fubara M et al. (2015) Earth system governance in Africa: knowledge and capacity needs. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 14:198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.06.009

Kates RW, Travis WR, Wilbanks TJ (2012) Transformational adaptation when incremental adaptations to climate change are insufficient. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109(19):7156–7161. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1115521109

Kinley R (2017) Climate change after Paris: from turning point to transformation. Clim Pol 17(1):9–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1191009

Klein RJT, Eriksen SEH, Næss LO, Hammill A, Tanner TM et al. (2007) Portfolio screening to support the mainstreaming of adaptation to climate change into development assistance. Clim Chang 84(1):23–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-007-9268-x

Levy DL, Spicer A (2013) Contested imaginaries and the cultural political economy of climate change. Organization 20(5):659–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508413489816

Lockwood M (2013) What can climate-adaptation policy in sub-Saharan Africa learn from research on governance and politics? Development Policy Review 31(6):647–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12029

MAFC (2014) Tanzania Agriculture Climate Resilience Plan 2014–2019, Ministry of Agriculture, Food Security and Cooperatives

Mallin M-AF (2018) From sea-level rise to seabed grabbing: the political economy of climate change in Kiribati. Mar Policy 97:244–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.04.021

Maro PS (2008) A review of current. Tanzanian national environmental policy Geographical Journal 174(2):149–175. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40205211

Mikulewicz M (2020) The discursive politics of adaptation to climate change. Annals of the American Association of Geographers. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1736981

Mittal N, Vincent K, Conway D, Archer van Garderen E, Pardoe J et al. (2017) Future climate projections for Malawi. Future Climate For Africa Country Climate Brief, 12. http://www.futureclimateafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2772_malawi_climatebrief_v6.pdf

Nachmany M (2018) Climate change governance in Tanzania: challenges and opportunities. Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy Policy brief, 8. http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Climate-change-governance-in-Tanzania-challenges-and-opportunities.pdf

Nachmany, M., Fankhauser, S., Setzer, J., Averchenkova, A. (2017) Global trends in climate change legislation and litigation, 2017 update. Grantham research institute on climate change and the environment. http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/publication/global-trends-in-climate-change-legislation-and-litigation-2017-update/

Næss LO, Polack E, Chinsinga B (2011) Bridging research and policy processes for climate change adaptation. Institute of Development Studies Bulletin 42(3):97–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2011.00227.x

Næss LO, Newell P, Newsham A, Phillips J, Quan J (2015) Climate policy meets national development contexts: insights from Kenya and Mozambique. Glob Environ Chang 35:534–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.08.015

Nightingale A (2017) Power and politics in climate change adaptation efforts: struggles over authority and recognition in the context of political instability. Geoforum 84:11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.05.011

Nightingale AJ, Eriksen S, Taylor M, Forsyth T, Pelling M et al. (2019) Beyond technical fixes: climate solutions and the great derangement. Clim Dev. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1624495

Pardoe J, Vincent K, Conway D (2018a) How do staff motivation and workplace environment affect capacities to adapt to climate change in developing countries? Environ Sci Policy 90:46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.09.020

Pardoe J, Conway D, Namaganda E, Vincent K, Dougill AJ et al. (2018b) Climate change and the water-energy-food nexus: insights from policy and practice in Tanzania. Clim Pol 18(7):863–877. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1386082

Patton MQ (1980) Qualitative evaluation methods. Sage, Beverly Hills

Paterson M, P-Laberge X (2018) Political economies of climate change. WIREs Climate Change 9:e506. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.506

Pelling M, O'Brien K, & Matyas D (2015) Adaptation and transformation. Climatic Change 133(1):113–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1303-0

Persson Å, Remling E (2014) Equity and efficiency in adaptation finance: initial experiences of the adaptation fund. Clim Pol. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2013.879514

Remling E, Persson Å (2015) Who is adaptation for? Vulnerability and adaptation benefits in proposals approved by the UNFCCC Adaptation Fund. Clim Dev 7(1):16–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2014.886992

Republic of Zambia (2007) Formulation of the National Adaptation Programme of Action. Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Natural Resources, Lusaka

Republic of Zambia (2011a) National Climate Change Communication and Advocacy Strategy. Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Natural Resources, Lusaka

Republic of Zambia (2011b) National Climate Change Response Strategy. Ministry of Local Government, Housing, Early Education and Environmental Protection, Lusaka

Ricks JI, Liu AH (2018) Process-tracing research designs: a practical guide. PS: Political Science & Politics 51(4):842–846. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518000975

Smucker TA, Wisner B, Mascarenhas A, Munishi P, Wangui EE et al. (2015) Differentiated livelihoods, local institutions, and the adaptation imperative: assessing climate change adaptation policy in Tanzania. Geoforum 59:39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.11.018

Sovacool BK, Linnér B-O (2015) The political economy of climate change adaptation. Palgrave MacMillan, New York

Sovacool BK, Linnér B, Goodsite ME (2015) The political economy of climate adaptation. Nat Clim ChangNature Climate Change 5:616–618

Sovacool BK, Tan-Mullins M, Ockwell D, Newell P (2017) Political economy, poverty, and polycentrism in the global environment facility’s least developed countries fund (LDCF) for climate change adaptation. Third World Q 38(6):1249–1271. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1282816

Tanner T, Allouche J (2011) Towards a new political economy of climate change and development. Institute of Development Studies Bulletin 42(3):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2011.00217.x

Tschakert P, Das PJ, Pradhan NS, Machado M, Lamadrid A et al. (2016) Micropolitics in collective learning spaces for adaptive decision making. Glob Environ Chang 40:182–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.07.004

Uittenbroek CJ (2016) From policy document to implementation: organizational routines as possible barriers to mainstreaming climate adaptation. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 18(2):161–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1065717

URT (2007) National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA). Vice President’s Office, Division of Environment, Dar es Salaam

URT (2011). National five year development plan 2011/2012–2015/2016. President’s office, Planning Commission, Dar es Salaam

URT (2012a) National Climate Change Strategy. United Republic of Tanzania Vice President’s Office, Division of Environment, Dar es Salaam

URT (2012b) National Climate Change Communication Strategy (2012–2017) United Republic of Tanzania Vice President’s Office, Division of Environment, Dar es Salaam

URT (2012c) Guidelines for integrating climate change adaptation into National Sectoral Policies, Plans and Programmes of Tanzania. United Republic of Tanzania Vice President’s Office, Division of Environment, Dar es Salaam

URT (2016) National five year development plan 2016/17–2020/2021. Ministry of Finance and Planning, Dar es Salaam

URT (2018) The project on the revision of National Irrigation Master Plan. Final Report, vol 1. National Irrigation Commission, Ministry of Water and Irrigation, The United Republic of Tanzania

Vincent K, Dougill AJ, Dixon JL, Stringer LC, Cull T (2015) Identifying climate services needs for national planning: insights from Malawi. Clim Pol 17(2):189–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1075374

Yanguas P, Hulme D (2015) Barriers to political analysis in aid bureaucracies: from principle to practice in DFID and the World Bank. World Dev 74:209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.009

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Emilinah Namaganda, Ruth Emmanuel, Japhet Kashaigili, Diana Mataya and Michal Nachmany for support with fieldwork and data collection.

Funding

This work was carried out under the Future Climate For Africa UMFULA project, with financial support from the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), grant references: NE/M020398/1 (LSE), NE/M020010/1 (Kulima), NE/M02007X/1 (CSIR), NE/M020177/1 (University of Leeds) and NE/M020509/1 (LUANAR), and the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID); and with financial support from the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) through the Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, grant numbers ES/R002371/1 (LSE) and ES/K006576/1 (Leeds). Further insights draw on work carried out under the British Academy project ‘The governance and implementation of the SDG13 on Climate Change’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Communicated by James Ford

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pardoe, J., Vincent, K., Conway, D. et al. Evolution of national climate adaptation agendas in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia: the role of national leadership and international donors. Reg Environ Change 20, 118 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01693-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01693-8