Abstract

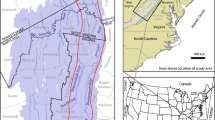

The hydraulic conductance of a large fault zone has been estimated by calibrating a regional groundwater flow model. Drops in groundwater elevations of over 80 m have been observed along a 15-km length of the Mission Creek fault, California, USA. The large drops in elevation are attributed to the reduced hydraulic conductivity of the fault materials. A conceptual and numerical model of the two hydrologic subbasins in Desert Hot Springs, separated by the Mission Creek fault, was developed. The model was used to estimate the hydraulic conductance along the fault. The parameter estimation involved calibrating the model with observed groundwater elevations from over 40 locations over a 60-year period. The fault hydraulic conductances were estimated assuming a linear trend in the fault length, yielding variations in the fault hydraulic conductance of about an order of magnitude along the fault length (2 × 10−11–4 × 10−10 1/s). When an average fault thickness of 35 m is assumed, the fault hydraulic conductivity values are estimated to be from three to five orders of magnitude lower than the surrounding materials. A sensitivity analysis indicated that assumptions made in the conceptual model do not significantly affect estimated fault hydraulic conductances.

Résumé

La conductance hydraulique d’une zone présentant une large faille a été estimée grâce à la calibration d’un modèle hydrogéologique régional d’écoulement. Des chutes de niveaux piézométriques de plus de 80 m ont été observées le long de la faille de Mission Creek en Californie, Etats-Unis, sur une longueur de 15 km. Les importantes baisses de niveau sont attribuées à la faible conductivité hydraulique des matériaux de la faille. Un modèle conceptuel et numérique des deux sous-bassins hydrologiques du Desert Hot Springs, séparés par la faille de Mission Creek a été élaboré. Le modèle a été utilisé pour estimer la conductance hydraulique le long de la faille. L’estimation de ce paramètre a impliqué de calibrer le modèle avec les niveaux piézométriques observés au niveau de 40 localisations sur une période de 60 ans. Les conductances hydrauliques de la faille ont été estimées avec l’hypothèse d’une tendance linéaire sur la longueur de la faille, accommodant les variations des valeurs de conductance hydraulique de la faille d’environ un ordre de grandeur le long de la longueur de la faille (2 × 10−11–4 × 10−10 s−1). Lorsque l’épaisseur moyenne de la faille est supposée de 35 m, les valeurs de conductivité hydraulique de la faille sont estimées être entre 3 à 5 ordres de grandeurs inférieurs par rapport aux matériaux environnants. Une analyse de sensibilité a indiqué que les hypothèses formulées dans le modèle conceptuel n’affectent pas de manière significative les conductances hydrauliques estimées de la faille.

Resumen

Se ha estimado la conductancia hidráulica de una gran zona de falla, mediante la calibración de un modelo de flujo regional de agua subterránea. Se han observado caídas en las elevaciones del agua subterránea por encima de 80 m a lo largo unos 15-km de longitud de la falla Mission Creek, California, EE.UU. Se atribuyen los descensos grandes en la elevación, a la conductibilidad hidráulica reducida de los materiales de la falla. Se desarrollaron un Modelo conceptual y numérico de las dos subcuencas hidrológicas en el Desierto Hot Springs, separadas por la falla de Misión Creek. El modelo fue utilizado para estimar la conductancia hidráulica a lo largo de la falla. La estimación del parámetro involucró calibrar al modelo, con las elevaciones del agua subterránea observadas en más de 40 localidades y por un periodo mayor a 60 años. Las conductancias hidráulicas de la falla se estimaron asumiendo una tendencia lineal en la longitud de la falla, obteniendo variaciones en la conductancia hidráulica de la falla, de alrededor de un orden de magnitud a lo largo de la longitud de la falla (2 × 10−11–4 × 10−10 s−1). Cuando es supuesto un espesor medio de la falla de 35 m, se estiman los valores de conductibilidad hidráulicos de la falla, de tres a cinco órdenes de magnitud más bajos que los de materiales circundantes. Un análisis de sensibilidad indicó, que los supuestos hechos en el modelo conceptual, no afectan significativamente las conductancias hidráulicas estimadas de la falla.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bear J (1979) Hydraulics of groundwater. McGraw-Hill, New York

Bense VF, Vanden Berg EH, Van Balen RT (2003) Deformation mechanisms and hydraulic properties of fault zones in unconsolidated sediments: the Roer Valley Rift System, The Netherlands. Hydrogeol J 11:319–332

Bredehoeft JD, Belitz K, Sharp-Hansen S (1992) The hydrodynamics of the Big Horn Basin: a study of the role of faults. AAPG Bull 76:530–546

Caine JS, Forster CB (1999) Fault zone architecture and fluid flow: insights from field data and numerical modeling, in faults and subsurface flow in the shallow crust. AGU geophysical monograph, vol 113. American Geophysical Union, Washington, DC

Caine JS, Evans JP, Forster CB (1996) Fault zone architecture and permeability structure. Geology 24:1025–1028

California Department of Water Resources (1964) Coachella Valley investigation: bulletin 108, CDWR, Sacremento, CA, USA

California Department of Water Resources (1979) Coachella Valley area well standards investigation: southern district, CDWR, Sacremento, CA, USA

Doherty J (1994) PEST, Watermark Computing, Corinda, Australia

Ganser DR (1987) Hydrogeologic characteristics of the Ramapo fault, northern New Jersey. Ground Water 25:664–671

Geotechnical Consultants, Inc. (1979) Hydrogeologic investigation-mission creek subbasin within the Desert Hot Springs County Water District, Geotechnical Consultants, Inc., Westerville, OH, USA

Geotechnical Consultants, Inc. (1992) Groundwater resources: update, a Report for Mission Springs Water District, Summary of Findings and Conclusions with Recommendations, Desert Hot Springs, California, Geotechnical Consultants, Inc., Westerville, OH, USA

Haneberg WC (1995) Steady-state groundwater flow across idealized faults. Water Resour Res 31:1815–1820

Harding Lawson Associates (1985) Geothermal Resource Assessment and Exploration of Desert Hot Springs, Harding Lawson Associates, California, Novato, California

Heynekamp MR, Goodwin LB, Mozley PS, Haneberg WC (1999) Controls on fault-zone architecture in poorly lithified sediments, Rio Grande Rift, New Mexico: implications for fault-zone permeability and fluid flow, faults and subsurface fluid flow in the shallow crust, geophysical monograph 113, American Geophysical Union, Washington, DC, pp 51–68

Hsieh PA, Freckleton JR (1993) Documentation of a computer program to simulate horizontal-flow barriers using the US Geological Survey’s Modular three-dimensional finite-difference ground-water flow model. US Geol Surv Open-File Rep 92–477

Huntoon PW (1985) Fault severed aquifers along the perimeters of Wyoming artesian basins. Ground Water 23:176–181

Huntoon PA, Lundy DA (1979) Fracture-controlled ground-water circulation and well siting in the vicinity of Laramie, Wyoming. Ground Water 17:463–469

Kolm KE, Downey JS (1994) Diverse flow patterns in the aquifers of the Amargosa Desert and vicinity, southern Nevada and California. Bull Assoc Eng Geol 31:33–47

Lines GC, Bilhorn TW (1996) Riparian vegetation and its water use during 1995 along the Mojave River, southern California. US Geol Surv Water-Resour Invest Rep 96-4241

Lopez D, Smith L (1996) Fluid flow in fault zones: Influence of hydraulic anisotropy and heterogeneity on the fluid flow and heat transfer regime. Water Resour Res 32:3227–3238

Lukkarila C (1999) Refinement of a groundwater flow model: upper Coachella Valley, Riverside County, California, MSc Thesis, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI, USA

Marler J, Ge S (2003) The permeability of the Elkhorn Fault Zone: a case study from South Park, Colorado. Ground Water 41:321–332

May WL (1996) Characterization of a large fault zone as a barrier to fluid flow, San Andreas Fault, near Desert Hot Springs, Riverside County, California. MSc Thesis, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI, USA

Mayer AS, May WL (1998) Mathematical modeling of proposed artificial recharge of the Mission Creek Subbasin. Dept. of Geological Engineering and Sciences. Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI, USA

McDonald MG, Harbaugh AW (1988) A modular three-dimensional finite-difference ground-water flow model In: US Geological Survey Techniques of Water Resources Investigations, Book 6, Chapter A1, US Geol Surv, Reston, VA, USA

Mozley PS, Davis JMD (1996) Relationship between oriented calcite concretions and permeability correlation structure in an alluvial aquifer, Sierra Ladrones Formation, New Mexico. J Sediment Res A66:11–16

Mozley PS, Goodwin L (1995) Patterns of cementation along a Cenozoic normal fault: a record of paleoflow orientations. Geology 23:539–542

Mozley PS, Beckner J, Whitworth TM (1995) Spatial distribution of calcite cement in the Santa Fe Group, Albuquerque Basin, NM: implications for groundwater resources. In: Spec Issue: Albuquerque Basin: studies in hydrogeology. New Mexico Geol 17:88–93

Proctor RJ (1968) Geology of the Desert Hot Springs-Upper Coachella Valley Area, Special Report 94, California Division of Mines and Geology, Sacremento, CA

Rasmussen GS (1979) Engineering Geology Investigations, project #1430, 100-acre parcel, North of Dillon Rd., East of Long Canyon Rd., Desert Hot Springs, CA, Gary S. Rasmussen and Associates, San Bernardino, CA, USA

Reichard EG, Meadows JK (1992) Evaluation of a ground-water flow and transport model of the Upper Coachella Valley, California, US Geol Surv Water-Resour Invest Rep 91-4142

Seber GAF, Wild CJ (1989) Nonlinear regression. Wiley, New York, p 768

Sigda JM, Goodwin LB, Mozley PS, Wilson JL (1999) Permeability alteration in small-displacement faults in poorly lithified sediments: Rio Grande Rift, Central New Mexico. In: Faults and subsurface fluid flow in the shallow crust, Geophysical Monograph 113, American Geophysical Union, Washington, DC, pp 51–68

Smith L, Forster C, Evans J (1990) Interaction of fault zones, fluid flow, and heat transfer at the basin scale. In: Neuman SP, Neretnieks I (eds) Hydrogeology of low permeability environments. Verlag Heinz Heise, Hanover, Germany, pp 41–67

Swain LA (1978) Predicted water-level and water quality effects of artificial recharge in the Upper Coachella Valley, California, using a finite element digital model. US Geol Surv Water-Resour Invest Rep 77–29

Tyley SJ (1971) Analog model of the ground-water basin of the Upper Coachella Valley, California. US Geol Surv Open-File Rep 7417-03

Tyley SJ (1974) Analog model study of the ground-water basin of the Upper Coachella Valley, California. US Geol Surv Water-Suppl Pap 2027

Vander Velpen BPA, Sporry RJ (1993) Resist: a computer program to process resistivity sounding data on PC compatibles. Comput Geosci 19:691–703

Zhody AAR, Eaton GP, Mabey DR (1974) Application of surface geophysics to ground-water investigations. Techniques of water-resources investigations of the United States Geological Survey, Chapter D1, US Geological Survey, Reston, VA, USA

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. James Wood at Michigan Technological University (MTU) for the original suggestion to investigate the Mission Creek fault zone as a barrier to groundwater flow. The cooperation of the Mission Springs Water District (MSWD), Desert Hot Springs, California, especially Mr. John L. Morgan, has been essential to this study. The authors gratefully acknowledge the sources of funding for this study: the Petroleum Research Fund, MSWD, and MTU. Eric Reichard at the US Geological Survey (USGS) Water Resources Division office in San Diego, California was kind enough to provide historical data for pumpage and groundwater levels. Michael Rymer and Rufus Catchings of the USGS Earthquake Hazard Reduction office in Menlo Park, California provided interpretations of basement depths from their seismic-reflection surveys. Discussions with Dr. Jan Gillespie of the California State University, Bakersfield have been invaluable for refining the conceptual model of the groundwater-flow system.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mayer, A., May, W., Lukkarila, C. et al. Estimation of fault-zone conductance by calibration of a regional groundwater flow model: Desert Hot Springs, California. Hydrogeol J 15, 1093–1106 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-007-0158-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-007-0158-0