Abstract

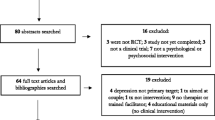

This study aims to investigate hospital admission of major depressive disorders (MDD) before and after birth. Population data for all primiparous women admitted to the hospital with depressive disorders before and after birth were used. The comparison group consisted of 10 % of primiparous women not admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder or substance use. A total of 728 women had a first admission with depressive disorders (501 in the first postpartum year). The rate of first hospital admission for depressive disorders decreased during pregnancy and increased markedly in the first three months after birth (peaking in the second month with a rate of 10.74/1,000 person year and rate ratio of 12.56) compared with the 6 months prior to pregnancy. Admission remained elevated in the second postpartum year. Older maternal age, smoking, elective caesarian section and admission to a neonatal intensive care unit or special care nursery were associated with a higher rate of admission. Women born outside Australia and those most socioeconomically disadvantaged were less likely to be admitted to the hospital in the first postpartum year. Overall risk of hospital admission with depressive disorders rose significantly across the entire first postpartum year. This has significant implications for policy and service planning for women with mood disorders in the perinatal period.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Adhikari P (2006) Socio-economic indexes for areas: Introduction, use and future directions. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra

Almond P (2009) Postnatal depression: a global public health perspective. Perspectives in Public Health 129(5):221–227

Austin M-P (2006) To treat or not to treat: maternal depression, SSRI use in pregnancy and adverse neonatal effects. Psychol Med 36(12):1663–1670

Austin MP, Leader L (2000) Maternal stress and obstetric and infant outcomes: epidemiological findings and neuroendocrine mechanisms. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 40(3):331–337

Austin MP, Priest SR (2005) Clinical issues in perinatal mental health: new developments in the detection and treatment of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 112(2):97–104

Austin M-P, Hadzi-Pavlovic D et al (2010) Depressive and anxiety disorders in the postpartum period: how prevalent are they and can we improve their detection? Arch Women's Ment Health 13(5):395–401

Austin M-P, Highet N, et al. (2011a) The beyondblue clinical practice guidelines for depression and related disorders—anxiety, bipolar disorder and puerperal psychosis—in the perinatal period. A Guideline for Primary Care Health Professionals Providing Care in the Perinatal Period. beyondblue: the national depression initiative, Melbourne

Austin M-P, Colton J, et al. (2011b) The Antenatal Risk Questionnaire (ANRQ): acceptability and use for psychosocial risk assessment in the maternity setting. Women Birth. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2011.06.002

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2010) Mental health services in Australia 2007–08. Mental Health Series No. 12., Cat. No. HSE 88. AIHW, Canberra

Cliffe S, Black D et al (2008) Maternal deaths in New South Wales, Australia: a data linkage project. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 48(3):255–260

Cox JL, Murray D et al (1993) A controlled study of the onset, duration and prevalence of postnatal depression. Br J Psychiatry 163:27–31

Dayan J, Creveuil C et al (2006) Prenatal depression, prenatal anxiety, and spontaneous preterm birth: a prospective cohort study among women with early and regular care. Psychosom Med 68(6):938–946

Dudek-Shriber L (2004) Parent stress in the neonatal intensive care unit and the influence of parent and infant characteristics. Am J Occup Ther 58(5):509–520

Gaynes BN, Gavin N et al (2005) Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evid Rep/Technol Assess 118:1–225

Kendell RE, Rennie D et al (1981) The social and obstetric correlates of psychiatric admission in the puerperium. Psychol Med 11(2):341–350

Kendell RE, Chalmers JC et al (1987) Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry 150:662–673

Lasser K, Boyd JW et al (2000) Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA 284(20):2606–2610

Martins C, Gaffan EA (2000) Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant–mother attachment: a meta-analytic investigation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41(6):737–746

Milgrom J, Westley D et al (2004) The mediating role of maternal responsiveness in some longer term effects of postnatal depression on infant development. Infant Behav Dev 27(4):443–454

Mracog RK, Jenkins GJ et al (1992) The influence of maternal age on caesarean section rates. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 32(3):206–207

Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM et al (2006) New parents and mental disorders: a population-based register study. JAMA 296(21):2582–2589

Murray L, Arteche A et al (2011) Maternal postnatal depression and the development of depression in offspring up to 16 years of age. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr 50(5):460–470

National Centre for Classification in Health (1999) The international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision, Australian modification (ICD-10-AM). National Centre for Classification in Health, Sydney

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2007) Antenatal and postnatal mental health: The NICE guidelines on clinical management and service guidance CG45. The British Psychological Society & the Royal College of Psychiatrists, National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, London

O'Hara MW, Swain AM (1996) Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatr 8(1):37–54

Pawlby S, Sharp D et al (2008) Postnatal depression and child outcome at 11 years: the importance of accurate diagnosis. J Affect Disord 197:241–245

Rahman A, Bunn J et al (2007) Maternal depression increases infant risk of diarrhoeal illness: a cohort study. Arch Dis Child 92(1):24–28

Ratnarajah D, Schofield MJ (2007) Parental suicide and its aftermath: a review. J Fam Stud 13(1):78–93

Savitz DA, Stein CR et al (2011) The Epidemiology of hospitalized postpartum depression in New York State, 1995–2004. Ann Epidemiol 21(6):399–406

Schneider B, Philipp M et al (2001) Psychopathological predictors of suicide in patients with major depression during a 5-year follow-up. Eur Psychiatr 16(5):283–288

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (2007) SIGN 60. Postnatal depression and puerperal psychosis: A national clinical guideline. 2007 review. Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh

Wurmser H, Rieger M et al (2006) Association between life stress during pregnancy and infant crying in the first six months postpartum: a prospective longitudinal study. Early Hum Dev 82(5):341–349

Yang S-N, Shen L-J et al (2011) The delivery mode and seasonal variation are associated with the development of postpartum depression. J Affect Disord 132(1–2):158–164

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank data custodians Lee Taylor, Kim Lim and Tony Dunn of the NSW Department of Health, Glenda Lawrence of the Centre for Health Record Linkage (CheReL) and John Lumby and Pia Salmelainen of the Pharmaceutical Services Branch of NSW Health for providing the data, undertaking the linkage and providing expert technical advice. The Perinatal & Women’s Mental Health Unit gratefully acknowledges infrastructure funding of St John of God Health Care. We acknowledge the families who have contributed their data to this study. Funding for this study was provided by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Training Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, F., Austin, MP., Reilly, N. et al. Major depressive disorder in the perinatal period: using data linkage to inform perinatal mental health policy. Arch Womens Ment Health 15, 333–341 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0289-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0289-8