Abstract

This study develops a model in which a “genuine” producer supplying genuine products competes with competitive “third-party” producers supplying compatible third-party products. We use this model to examine (i) how the strategic behavior of the genuine producer to drive out third parties (running comparative advertising, establishing technical barriers) affects the market equilibrium, (ii) whether the government should regulate such behavior by the genuine producer, and (iii) whether the government should regulate the entry of firms that supply third-party products. We find that a small amount of spending on advertising and creating technical barriers improves social welfare. However, their amounts in market equilibrium are socially excessive because the negative effects (e.g., the cost of advertising and creating barriers and an increase in production cost for third parties) outweigh the positive effects (e.g., an increase in the consumption of the genuine product and mitigation of the distortion of insufficient supply). Furthermore, we find that prohibitive measures (e.g., prohibition of advertising and technical barriers, entry prohibition of third-party producers) may improve welfare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although third-party products cover other types of products in a broad sense, in this paper, we use the terms non-genuine and third-party products interchangeably. For example, products compatible with genuine products, such as non-genuine printer inks, are considered third-party products.

Bronnenberg et al. (2012) examined the pace of the dissipation of brand loyalty using consumption and interstate migration data.

Jiang and Shan (2018) empirically investigated the effect of various product attributes on the willingness-to-pay of consumers for genuine luxury brands.

A survey on brand-name products found that two-thirds of consumers are satisfied with fake products (“ANALYSIS: Keeping it real,” IN-STORE Aug 2007 9–11). Moreover, Varela et al. (2021) conducted a questionnaire survey for Portuguese consumers, and found that more than half of respondents have the experience of purchasing counterfeit luxury brands and that the main motivation is low price.

In this paper, we use the terms comparative advertising and persuasive advertising interchangeably. Chakravarti and Janiszewski (2004) used choice experiments on food products to show that even general advertising may create brand loyalty by emphasizing specific product attributes. As a result, consumers strengthen their preferences for branded products, which are perceived as being of “high quality” in terms of these attributes.

Companies that supply data management services and software often provide the information on this charging issue and recommend the use of certified cables. For example, see the website of AOMEI (https://www.ubackup.com/phone-backup/fix-iphone-charging-issues-after-update.html), Tenorshare (https://www.tenorshare.com/ios-12/fix-iphone-wont-charge-after-ios-12-update.html) (viewed 30 October 2022).

Battles for office machine after-products have been observed for several decades. In 1995, Hewlett-Packard, Canon, and Seiko Epson sued Nu-Kote—a supplier of non-genuine ink cartridges—for patent infringements. See The New York Times article titled “Patents,” on October 30, 1995.

Jeff also concluded the following: Deciding between brand-name and third-party alternatives partially depends on how you plan to use your prints: If your prints tend to be for one-time-only office presentations, text documents for school, or temporary color images (such as plain-paper photos), inks from third-party supplies may be a reasonable cost-saving option. The article in The New York Times, titled “New printer cartridge or a refill? Either way, ink is getting cheaper,” drew similar conclusions about this consumer choice problem (February 4, 2006).

A seller of refilled ink cartridges, Ecorica Inc., sued Canon for a violation of the Anti-Monopoly Law. See the article of Asahi Shimbun titled “Run on empty: Recycled ink cartridge maker to sue Canon Inc,” on October 25, 2020 (https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/13868980. viewed 30 October 2022).

The ink cartridges market is also an excellent example of government regulation. Printer manufacturers hold numerous patents on ink/toner cartridges, which yield higher-quality prints. However, patents can also be used to drive out third-party products. Multiple lawsuits have been filed on this issue over the past two decades. For example, in 2001, Epson filed a patent infringement lawsuit against a third-party ink cartridge producer in China. Epson also sued and won against other third parties in 2005. See the following articles: “Epson files patent infringement lawsuit against prominent replacement cartridge manufacturer (Business Wire, April 17, 2001),” “Seiko Epson wins ink cartridge patent suit in the United States (Jiji Press English News Service, March 11, 2005). Moreover, Canon and Epson also claimed that recycled ink cartridges infringed upon their patents and requested an injunction in Japan. However, both companies lost these lawsuits in 2004 and 2006, respectively. The presiding judge determined that the patents under consideration lacked novelty. See the following articles: “Court ruling on cartridge deals blow to Canon (FT.com, December 8, 2004),” and “Seiko Epson loses suit on ink cartridge patent (Jiji Press English News Service, October 18, 2006).” In 2011, Canon won another lawsuit against six third-party producers related to Canon’s patent infringement on LED cartridges. Although lawsuits have drawn a great deal of attention to date, regulation policies clearly influence the competition between genuine producers and third parties.

See Bagwell (2007) for a survey on the economics of advertising.

Persuasive advertising has also been analyzed in the field of consumer research. For example, Rajagopal and Montgomery (2011) examined the effect of false memories on consumer behavior and showed that exposure to imagery-evoking advertising could result in erroneous beliefs.

Mizuno and Odagiri (1990) considered a situation in which firms spend on advertising and R &D. However, they did not consider regulations and welfare.

Consider the example of street vendors who sell imitation goods close to a departmental store or genuine shop. In some cases, imitation vendors can be legally driven out because selling such goods is regarded as piracy. However, in other cases, vendors are not prohibited from selling imitation goods (See, for example, Rozhon and Thorner 2005). Authorities can establish rules for vending, such as regulations on the places where vendors conduct their business. Moreover, genuine shops can hire security guards to prevent street vendors from selling imitation goods in front of their shops. In both cases, the cost of selling imitation goods increases for street vendors. The former is considered a government intervention, whereas the latter is regarded as a technical barrier.

Another application of vertical quality differentiation models is eco-labels. By setting the criteria for certification, the government can create two types of products: green (high-quality) products and brown (low-quality) products—considering the environment and sustainability. Consumers can distinguish green products from brown products by identifying eco-labels. By setting a minimum quality standard for entry, the government may drive out all brown products from the market. There has also been considerable research on eco-labeling policies using vertical differentiation models (Amacher et al. 2002; Conrad 2005; Ibanez and Grolleau 2008; Brécard 2014; Li and van’t Veld 2015; Fischer and Lyon 2019; Poret 2019; Heyes et al. 2020).

Under certain conditions, the same results are obtained even with a general distribution of consumers. See “Appendix A.1” section for details.

As noted below, the market is fully covered in the present setting of the model. See Assumption 1.

In the literature, when competition between brands or quality choices are focused on, it is often assumed that all entrants have market power (Tremblay and Polasky 2002; Amacher et al. 2002; Conrad 2005; Hattori and Higashida 2015; Roger 2017). However, when competition between brands and non-brands or the entry of counterfeits is focused on, competitive producers of non-brands or counterfeits are often assumed to not have any market power (Tsai and Chiou 2012; Tsai et al. 2012; Pan 2020). An exception is Banerjee (2003), who assumed duopoly. The number of non-genuine producers is usually larger than that of genuine producers in the real world (e.g., suppliers of printer inks, vendors of imitation goods). Thus, following the literature and reflecting real-world situations, we assume a competitive supply of third-party products.

We assume the marginal cost, b, is constant, although it increases or decreases depending on firm 1’s strategy or the government’s regulation. However, even if we consider an upward-sloping supply curve for third-party products, the same results are obtained. See “Appendix A.2” section for details.

This assumption is crucial for obtaining interior solutions. See “Appendix A.3” section for details.

We follow pre-advertising welfare, as defined by Dixit and Norman (1978).

As all of the endogenous variables are determined by firm 1 without regulations by the government, the sequential and simultaneous choice of variables leads to the same result at the market equilibrium.

Even if we assume positive marginal production costs, such as \(c_1(>0)\) and \(c_2(>0)\), the same results are obtained in the following analysis. In such cases, G is defined as \((v_1-c_1)-(v_2-c_2)\), which is the true quality cost gap between the two types of products. We will refer to this point in Sect. 3.3 when discussing desirable regulation.

The second inequality in Assumption 1 ensures that the SOCs and the stability condition are satisfied:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial ^2 \pi ^*_1}{\partial s^2} = -\frac{(2\mu _s -1)}{2}<0, \quad \frac{\partial ^2 \pi ^*_1}{\partial b^2} = -\frac{(2\mu _b-1)}{2} <0, \quad \frac{\partial ^2 \pi ^*_1}{\partial s^2} \frac{\partial ^2 \pi ^*_1}{\partial b^2} -\left( \frac{\partial ^2 \pi ^*_1}{\partial s \partial b}\right) ^2 >0. \end{aligned}$$Note that the price of good \(1\) should also be controlled by the government to achieve the first-best situation. We do not consider a situation in which the government controls the price. Thus, going forward, “optimal” implies “second best.”

Further, the government may have tools available to set entry barriers for third-party producers. For example, as noted in the introduction, technical barriers are considered to increase as patent protection becomes stricter. Patent laws may play a key role in establishing entry barriers for generic drugs in the pharmaceutical markets. Using data from the Canadian pharmaceutical market, McRae and Tapon (1985) found that patented drugs can deter or restrict the entry of generics even after patent expiration because brand loyalty is created not only among consumers but also among physicians. If brand loyalty is made among physicians, generic producers incur an additional cost to persuade physicians to prescribe their products by convincing them that they are of the same quality as brand-name drugs. This leads to an increase in \(b\) in our model. Langinier (2004) theoretically demonstrated that a patent holder’s process innovation might deter the entry of followers in a small market. In this case, entry deterrence is achieved directly by decreasing the marginal production cost of the brand-name drugs. This effect implies that the relative marginal cost of producing generics increases. In this respect, process innovations have the same effect as an increase in \(b\). Moreover, Jones et al. (2001) empirically demonstrated that patent extensions in Canada decrease the entry of generics and mitigate competition in the pharmaceutical market. Assuming that the cost of technical barriers (\(C_b(b)\)) is the operational cost of the government policy, our analysis can be applied to the case in which the government explicitly sets up entry barriers.

Hattori and Higashida (2012, 2015) obtained similar results, i.e. excess amounts of advertising at the market equilibrium in terms of welfare, under duopoly with product differentiation. In contrast, since (Glaeser and Ujhelyi 2010) assumed a positive externality in misleading advertising and demonstrated that misinformation is insufficient.

If the government can make consumers precisely recognize the level of advertising by announcing a regulation, consumers will make purchasing decisions based on true utility, and accordingly, the genuine producer loses an incentive to create comparative advertising. Thus, any regulation leads to a complete prohibition of advertising. However, following Hattori and Higashida (2012, 2014, 2015), we assume that consumers are naïve, do not understand the meaning of regulations precisely, and observe only \(v_1 + s\). Moreover, since a positive level of advertising is optimal, the government does not have an incentive to exert any effort to make consumers understand the true value of s.

Theoretically, the other type of partial regulation can be considered: That is, the government determines the advertising level and then, firm 1 chooses the level of technical barriers. This type of partial regulation can be analyzed in a similar way and similar results are obtained.

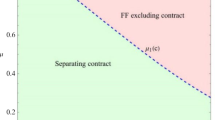

When \(v_1 = v_2\), \(G=0\). Thus, the inequalities in Propositions 1(ii) and 2(ii) never holds. This fact can also be confirmed in Fig. 1. The locus of \(v_1 = v_2\) always above both the dashed and dotted lines. Moreover, it is easily verified from (13) that \(\partial W^*/\partial b <0\) at \(s=b=0\) when \(v_1 =v_2\). This result holds even if we introduce an additional heterogenous evaluation for the non-genuine product as Tsai and Chiou (2012) assumed: \(u_{s,2} = v_2 - p_2 + \gamma \theta , \, 0<\gamma <1\).

We can simply introduce a fixed operation cost into the analysis.

The gross surplus of good \(1\) is defined in Sect. 3.1: \(u_{t,1} + p_1\). Similarly, the gross surplus of good \(2\) is defined as \(u_{t,2}+p_2- b\). Since \(p_2 = b\), the gross surplus of good \(2\) is equal to the true surplus (\(u_{t,2}\)).

See the “Appendix C” section for the details.

For example, in the case of Japan, the Consumer Affairs Agency regulates some types of advertising, such as false advertising, whereas the Fair Trade Commission regulates technical barriers.

Cubbin and Domberger (1988) empirically demonstrated that incumbents increase advertising expenditure to create brand loyalty in response to the entry of new rivals.

In the case of fake designer goods, such as bags and wallets, see the following articles: O’connell and Hudson (2006); Anonymous, May 11, 2011, “South Korean capital’s government clamps down on fake goods,” BBC Monitoring Asia Pacific; Arceo-Dumlao (2011). Leung (2013) used a survey and a conjoint analysis to show that there is still a high demand for pirated versions of the Microsoft software in Hong Kong, despite the Hong Kong government enforcing a strict copyright protection policy.

Firm 1 necessarily chooses partial coverage in this case. See “Appendix E” section For the proof.

Because \(p_1 =x_1\) holds in equilibrium (5), the price of the genuine product is lower under the entry prohibition of third parties in the presence of advertising than at market equilibrium. This price relationship with and without third parties’ entry is sometimes observed in the pharmaceutical market and has been investigated both theoretically and empirically. For example, Frank and Salkever (1992) theoretically examined the price effect of generic entry. They demonstrated that brand-name producers stop selling their products to price-elastic consumers and focus instead on loyal price-inelastic consumers. Thus, generic entry increases the price of brand-name drugs. The empirical findings of Frank and Salkever (1997) support this price change. On the other hand, using data on the Swedish pharmaceutical market, Bergman and Rudholm (2003) found that generic entry decreased brand-name drugs’ prices. See also Kong (2009); Berndt and Aitken (2011), among others. Moreover, using purchasing data on food products at grocery stores in the United States, (Ward et al. 2002) found that the entry of private brands, which correspond to third parties in our model, increases branded food products’ prices. Although prior empirical and theoretical findings indicate that the prices of brand names may increase or decrease in response to third parties’ entry, our model provides a channel for a price increase.

Firm 1 also chooses partial coverage in this case. See “Appendix E” section For the proof.

See Proposition 1 of Tsai and Chiou (2012) (p.11).

The basic mechanism by which persuasive advertising mitigates the inefficiencies caused by imperfect competition is also demonstrated by Hattori and Higashida (2012), although they focus on a duopoly with horizontal differentiation.

This sequential setting is a device used to clarify the results of this section. The setting of simultaneous determination leads to the same choices.

Qi (2019) referred to the complementarity between advertising and innovation in the context of entry deterrence behavior of an incumbent.

References

Amacher GS, Koskela E, Ollikainen M (2002) Environmental quality competition and eco-labeling. J Environ Econ Manag 47:284–306

Arceo-Dumlao T (2011) Louis Vuitton sees more harm than flattery in cheap imitations. Tribune Bus

Bagwell K (2007) The economic analysis of advertising. Handb Ind Organ 3:1701–1844

Banerjee DS (2003) Software piracy: a strategic analysis and policy instruments. Ind J Ind Organ 21:97–127

Belleflamme P, Forlin V (2020) Endogenous vertical segmentation in a Cournot duopoly. J Econ 131:181–195

Bennour K (2007) Advertising and entry deterrence: how the size of the market matters. Int J Bus Econ 6(3):199–206

Bergman MA, Rudholm N (2003) The relative importance of actual and potential competition: empirical evidence from the pharmaceutical market. J Ind Econ 51(4):455–467

Berndt ER, Aitken ML (2011) Brand loyalty, generic entry and price competition in pharmaceuticals in the quarter century after the 1984 Waxman-Hatch legislation. Int J Econ Bus 18(2):177–201

Bessen J, Maskin E (2009) Sequential innovation, patents, and imitation. RAND J Econ 40:611–635

Biancardi M, Di Liddo A, Villani G (2020) Fines imposed on counterfeiters and pocketed by the genuine firm. A differential game approach. Dyn Games Appl 10:1058–1078

Biancardi M, Di Liddo A, Villani G (2021) How do fines and their enforcement on counterfeit products affect social welfare? Comput Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-021-10195-6

Bonanno G (1986) Advertising, perceived quality and strategic entry deterrence and accommodation. Metroeconomica 38(3):257–280

Brécard D (2014) Consumer confusion over the profusion of eco-labels: lessons from a double differentiation model. Resour Energy Econ 37:64–84

Brester GW, SchroederT C (1995) The impacts of brand and generic advertising on mead demand. Am J Agric Econ 77:969–979

Bronnenberg BJ, Dubé JH, Gentzkow M (2012) The evolution of brand preferences: evidence from consumer migration. Am Econ Rev 102(6):2472–2508

Bunch DS, Smiley R (1992) Who deters entry? Evidence on the use of strategic entry deterrents. Rev Econ Stat 74(3):509–521

Cavaliere A, Crea G (2021) Brand premia driven by perceived vertical differentiation in markets with information disparity and optimistic consumers. J Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-021-00761-9

Ceccagnoli M (2005) Firm heterogeneity, imitation, and the incentives for cost reducing R &D effort. J Ind Econ 53:83–100

Chakravarti A, Janiszewski C (2004) The influence of generic advertising on brand preferences. J Consum Res 30:487–502

Chang Y, Sellak M (2021) Endogenous IPR protection, commercial piracy, and welfare implications for anti-piracy laws. Lett Appl Econ. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2021.1884832

Chen Z, Ross TW (1998) Orders to supply as substitutes for commitments to aftermarkets. Can J Econ 31(5):1204–1224

Conrad K (2005) Price competition and product differentiation when consumers care for the environment. Environ Resour Econ 31:1–19

Cubbin J (1981) Advertising and the theory of entry barriers. Economica 48:289–298

Cubbin J, Domberger S (1988) Advertising and post-entry oligopoly behavior. J Ind Econ 37(2):123–140

Dixit A, Norman V (1978) Advertising and welfare. Bell J Econ 9:1–17

Ellison G, Ellison SF (2011) Strategic entry deterrence and the behavior of pharmaceutical incumbents prior to patent expiration. Am Econ J Microecon 3:1–36

Elzinga KG, Mills DE (2001) Independent service organizations and economic efficiency. Econ Inq 39(4):549–560

Fischer C, Lyon TP (2019) A theory of multitier ecolabel competition. J Assoc Environ Resour Econ 6(3):461–501

Fong Y, Li J, Liu K (2016) When does aftermarket monopolization soften foremarket competition? J Econ Manag Strategy 25(4):852–879

Frank RG, Salkever DS (1992) Pricing, patent loss, and the market for pharmaceuticals. South Econ J 59(2):165–179

Frank RG, Salkever DS (1997) Generic entry and the pricing of pharmaceuticals. J Econ Manag Strategy 6(1):75–90

Gallini NT (1992) Patent policy and costly imitation. RAND J Econ 23:52–63

Glaeser EL, Ujhelyi G (2010) Regulating misinformation. J Public Econ 94:247–257

Hattori K, Higashida K (2012) Misleading advertising in duopoly. Can J Econ 45:1154–1187

Hattori K, Higashida K (2014) Misleading advertising and minimum quality standards. Inf Econ Policy 28:1–14

Hattori K, Higashida K (2015) Who benefits from misleading advertising? Economica 82:613–643

Heyes A, Kapur S, Kennedy PW, Martin S, Maxwell JW (2020) But what does it mean? Competition between products carrying alternative green labels when consumers are active acquirers of information. J Assoc Environ Resour Econ 7(2):243–277

Ibanez L, Grolleau G (2008) Can ecolabeling schemes preserve the environment? Environ Resour Econ 40:233–249

Jeff B (2008) Cheap ink: Will it cost you? PC World 26(8):93–98

Jiang L, Shan J (2018) Genuine brands or high quality counterfeits: an investigation of luxury consumption in China. Can J Adm Sci 35:183–197

Jones JCH, Potashnik T, Zhang A (2001) Patents, brand-generic competition and the pricing of ethical drugs in Canada: some empirical evidence from British Columbia, 1981–1994. Appl Econ 33:947–956

Kaserman DL (2007) Efficient durable good pricing and aftermarket tie-in sales. Econ Inq 45(3):533–537

Kessides IN (1986) Advertising, sunk costs, and barriers to entry. Rev Econ Stat 68(1):84–95

Klein MA (2020) Complementarity in public and private intellectual property enforcement; implications for international standards. Oxf Econ Pap 72(3):748–771

Klemperer P (1990) How broad should the scope of patent protection be? RAND J Econ 21:113–130

Kong Y (2009) Competition between brand-name and generics-analysis on pricing of brand-name pharmaceutical. Health Econ 18:591–606

Langinier C (2004) Are patent strategic barriers to entry? J Econ Bus 56:349–361

Leung TC (2013) What is the true loss due to piracy? Evidence from microsoft office in Hong Kong. Rev Econ Stat 95(3):1018–1029

Li Y, van’t Veld K (2015) Green, greener, greenest: eco-label gradation and competition. J Environ Econ Manag 72:164–176

Lyon TP, Huang H (1996) Innovation and imitation in an asymmetrically-regulated industry. Int J Ind Organ 15:29–50

Martínez-Sánchez F (2020) Preventing commercial piracy when consumers are loss averse. Inf Econ Policy 53:100896

McRae JJ, Tapon F (1985) Some empirical evidence on post-patent barriers to entry in the Canadian pharmaceutical industry. J Health Econ 4:43–61

Miao C (2010) Consumer myopia, standardization and aftermarket monopolization. Eur Econ Rev 54:931–946

Mizuno M, Odagiri H (1990) Does advertising mislead consumers to buy low-quality products? Int J Ind Organ 8:545–558

Morton FMS (2000) Barriers to entry, brand advertising, and generic entry in the US pharmaceutical industry. Int J Ind Organ 18:1085–1104

Novo-Peteiro JA (2020) Two-dimensional vertical differentiation with attribute dependence. J Econ 131:149–180

O’connell V, Hudson K (2006) Not our bag, Coach says in a lawsuit alleging target sold counterfeit purse. Wall Str J 3:A17

Pan C (2020) Competition between branded and nonbranded firms and its impact on welfare. South Econ J 87:647–665

Paton D (2008) Advertising as an entry deterrent: evidence from UK firms. Int J Econ Bus 15(1):63–83

Pepall LM, Richards DJ (1994) Innovation, imitation, and social welfare. South Econ J 60:673–684

Poret S (2019) Label wars: competition among NGOs as sustainability standard setters. J Econ Behav Organ 160:1–18

Qi S (2019) Advertising, industry innovation, and entry deterrence. Int. J Ind Organ 65:30–50

Qian Y (2014) Brand management and strategies against counterfeits. J Econ Manag Strateg 23(2):317–343

Qian Y, Gong Q, Chen Y (2015) Untangling searchable and experiential quality responses to counterfeits. Mark Sci 34(4):522–538

Rajagopal P, Montgomery NV (2011) I imagine, I experience, I like: the false experience effect. J Consum Res 38:578–594

Roger G (2017) Two-sided competition with vertical differentiation. J Econ 120:193–217

Rozhon T, Thorner R (2005) On the streets, genuine copies (and a few originals). N Y Times

Schmalensee R (1974) Brand loyalty and barriers to entry. South Econ J 40(4):579–588

Schmalensee R (1983) Advertising and entry deterrence: an exploratory model. J Polit Econ 91(4):636–653

Sembenelli A, Vannoni D (2000) Why do established firms enter some industries and exit others? Empirical evidence in Italian business groups. Rev Ind Organ 17:441–456

Tremblay V, Polasky S (2002) Advertising with subjective horizontal and vertical product differentiation. Rev Ind Organ 20:253–265

Tsai M, Chiou J (2012) Counterfeiting, enforcement and social welfare. J Econ 107:1–21

Tsai M, Chiou J, Lin CA (2012) A model of counterfeiting: a duopoly approach. Jpn World Econ 24:283–291

Varela M, Lopes P, Mendes R (2021) Luxury brand consumption and counterfeiting: a case study of the Prtuguese market. Innov Mark 17(3):45–55

Ward MB, Shimshack JP, Perloff JM, Harris JM (2002) Effects of the private-label invasion in food industries. Am J Agric Econ 84(4):961–973

Wright DJ (1999) Optimal patent breadth and length with costly imitation. Int J Ind Organ 17:419–436

Yao J (2005) Counterfeiting and an optimal monitoring policy. Eur J Law Econ 19:95–114

Zegners D, Kretschmer T (2017) Competition with aftermarket power when consumers are heterogeneous. J Econ Manag Strategy 26(1):96–122

Zellner JA (1989) A simultaneous analysis of food industry conduct. Am J Agric Econ 71(1):105–115

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Takanori Adachi and all participants of 2012 Autumn Meeting of Japanese Economic Association for helpful comments. We would also like to thank three anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions and Wiley and Editage for language editing. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from Zengin Foundation for Studies on Economics and Finance and JSPS KAKENHI (19K21693)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

A: On functional forms

1.1 A.1. General distribution function

Although we assume a uniform distribution for the consumers’ love of genuineness (\(\theta\)), the density may be generalized. As (1) holds even for general distributions, the demand for each type of product (2) can be rewritten as

where \(f(\cdot )\) is a probability density function. Then, the profits of firm 1 is

Similar to the case of a uniform distribution, the FOC for firm 1 in the second stage is given by

From (20), we obtain the second partial derivatives:

Thus, if \(-2f(\theta ) - p_1 f'(\theta )<0\), the SOC is satisfied. Moreover, if \(f(\theta ) + p_1 f'(\theta )>0\) holds, the positive relationship between advertising and the price of the genuine product holds as follows:

In the case of uniform distribution, these conditions hold because \(f'=0\). Moreover, it holds that

which is negative if the SOC is satisfied.

Using the envelope theorem, we also obtain the FOCs for firm 1 in the first stage:

which is similar to the FOC in the case of uniform distribution. The second partial derivatives are given by

Similar to the case of a uniform distribution, assuming that the size of the cost parameters (\(\mu _j\)) is larger than a certain level, the SOC in the first stage (21) is assured to hold as long as the SOC in the second stage is satisfied. Moreover, if the SOC in the second stage is satisfied, the stability condition is also satisfied.

An increase in the level of advertising (1) increases the price of the genuine product, and (2) shifts the demand from non-genuine to genuine products. Thus, consumers lose from the increase in advertising. However, firm 1 does not consider this loss of consumers when choosing its level of advertising. In addition to these effects, an increase in the level of technical barriers increases the marginal cost of the non-genuine product and its price. Thus, similar to the case of uniform distribution, the difference of the levels of advertising and technical barriers between those at the market equilibrium and the second-best optimum can be obtained.

Thus, the important factor for general distribution to generate the same result as a uniform distribution is the condition for the SOC in the second stage to hold. The same results are obtained if \(f'>0\), while the same results may not be generated if \(f'<0\). Considering any level of love of genuineness, \(\tilde{\theta }(0 \le \tilde{\theta }< \bar{\theta }\)). If the number of consumers with \(\tilde{\theta }\) increases as \(\tilde{\theta }\) becomes larger, the generalization of distribution does not change the results. Moreover, even if the number of consumers with \(\tilde{\theta }\) decreases as \(\tilde{\theta }\) becomes larger, the same results are obtained if the degree of the decrease is small.

1.2 A.2. Increasing marginal cost of non-genuine products

We assume a constant marginal cost of producing non-genuine products in the main text. However, even if we consider an upward sloping supply curve for third-party products, the same results are obtained. For simplicity, we consider a uniform distribution of the love of genuineness.

Let us consider a simple upward sloping curve as follows:

where \(c_2\) and \(\psi\) are the marginal cost of production for non-genuine products and a positive constant, respectively. Then, the marginal consumer who is indifferent between purchasing goods 1 and 2 is defined as:

The profits of firm 1 can be defined in the same way as the case of constant marginal cost of non-genuine products. Then, the FOC for firm 1 in the second stage is given by

Note that the SOC is satisfied: \(\partial ^2 \pi _1/\partial p^2_1 = -2/(1+\psi ) <0\). From the FOC above, the equilibrium values in the second stage are obtained as follows:

Thus, similar to the case of constant marginal cost of non-genuine products, the analyses for the first stage at the market equilibrium and for the second-best optimum can be conducted.

There is one additional effect from introducing an upward sloping supply curve. It is obtained from (23) that

which implies that the steeper the slope of the upward sloping supply curve of non-genuine products, the smaller is the equilibrium output of firm 1. When the slope is steep, the cost of the marginal third-party (the marginal seller of the non-genuine product) decreases greatly as the market share of firm 1 increases. In other words, firm 1 must decrease the price of its product greatly to gain additional consumers (to shift consumers from purchasing non-genuine to genuine products). However, the price decrease leads to the loss of profits from its existing customers. Thus, the steeper the slope of the upward sloping supply curve of non-genuine products, the weaker the incentive firm 1 has to increase its share. The same mechanism works when firm 1 chooses the levels of advertising and technical barriers in the first stage.

However, Eqs. (10), (11) reveal that the difference of the levels of advertising and technical barriers between the market equilibrium and the second-best optimum is generated by (1) the loss consumers incur caused by an increase in the price of genuine products; (2) the loss incurred by the marginal consumers who change their purchased products; and (3) the loss that consumers of non-genuine products face caused by an increase in the marginal cost of non-genuine products. These three factors exist even in the case of an upward sloping supply curve. Thus, the same results are obtained even in the case of upward sloping supply curves of non-genuine products.

1.3 A.3. Shapes of the cost functions of advertising and technical barriers

We assume a specific cost function of advertising and technical barriers, \(C_j (j) = \mu _j j^2/2 \, (j=s,b)\), which means that these cost functions are convex. To obtain interior solutions, the convexity of these cost functions is crucial, that is, \(C'_j (j) >0\) and \(C^{''}_j(j) >0\). To verify this point, consider the FOC for firm 1 in the first stage. In the case of general functional forms, (8) and (9) can be rewritten as:

Then, the second partial derivative is given by

Thus, when \(C^{''}_j \le 0\), firm 1 chooses zero or the maximum value for j.

For the government, the SOCs may be satisfied if the cost functions are linear or convex because the government not only considers the profits of firm 1 but also the consumer surplus (see 10 and 11). Moreover, even if the case with corner solutions is considered, we can examine the difference between the levels of advertising and technical barriers at the market equilibrium and the second-best optimum.

B: Proof of Propositions 1 and 2

First, we compare the advertising and technical barriers in the market equilibrium with those of the second-best optimum. From Table 1, we obtain:

Given that \(\mu _s>1\) and \(\mu _b>1\) hold, from Assumption 1, \(s^E-s^O>0\) holds. Moreover,

holds.

We also obtain

\(\mu _s>1\) and \(\mu _b>1\) hold from the second inequality of Assumption 1. \(\bar{\theta }>G\) also holds from the third inequality from Assumption 1. Then, as \(\mu _s (6\mu _s \mu _b -4\mu _s -1) -2\mu ^2_s \mu _b >0\), \(b^E-b^O>0\) holds. Moreover, as \(b^E>0\), it is obvious that \(b^E-b^o >0\).

Next, we examine the denominator of the equilibrium advertising and technical barriers in partial regulation (L).

As \(\mu _s>1\) and \(\mu _b>1\) hold from Assumption 1, the denominator is positive.

Next, we compare the advertising and technical barriers at the market equilibrium with those under partial regulation. From Table 1, we obtain:

Note that

holds. Recall that \(\mu _s>1\), \(\mu _b>1\), and \(\bar{\theta }>G\). If \(G \ge \bar{\theta }/2\), then \(2\mu _s\mu _b G > \mu _s \bar{\theta }\) holds. If \(G < \bar{\theta }/2\) and \(\mu _s>2\), then \(\mu _s(\mu _s \mu _b -1) \bar{\theta }> \mu ^2_s \mu _b G\) holds. Moreover, if \(\mu _s \le 2\), then \(s^E>s^L\) necessarily holds. Thus, \(s^E>s^L\) necessarily holds. We also obtain that

Thus, it is clear that \(s^E>s^l\).

Moreover, we obtain

The numerator is rewritten as:

The third inequality of Assumption 1 reveals that \(\bar{\theta }- G > 0\). Thus, the numerator is positive. \(b^E > b^L\) necessarily holds. As \(b^l =0\), it is obvious that \(b^E > b^l\).

C: The details for the welfare effect of complete strategy prohibition

We first investigate the sign of (17), which can be rewritten as:

The coefficient of \(\bar{\theta }^2\) is given by

It is easily verified that the coefficients of \(\bar{\theta }G\) and \(G^2\) are negative. Thus, the third effect is necessarily negative.

We next examine the overall effect. Summing up (15) through (17), we obtain the difference between welfare under the prohibition of both advertising and technical barriers and welfare at market equilibrium:

The third inequality of Assumption 1 reveals that \(\theta > G\). Moreover, the second inequality of Assumption 1 implies that \(\mu _b>1\). Thus, \(12\mu ^2_s \mu _b \bar{\theta }^2 - 2\mu ^2_s \bar{\theta }G - 4\mu ^2_s \mu _b G^2 >0\) holds. Consequently, \(W^C - W^E\) is positive.

D: Partial prohibition for the genuine producer

Let superscript \(J\) denote the case of partial prohibition. Firm 1 can use one of two strategies, \(j \, (j=s \, or \, b)\). The equilibrium price, consumption quantities, and levels of advertising/technical barriers are given as follows:

The total cost of running advertising and setting technical barriers is smaller under complete strategy prohibition than under partial prohibition. Thus, the benefit (cost saving) caused by the change from partial prohibition to complete strategy prohibition is

Having said that, the quantity of genuine products consumed under partial prohibition is greater than that under complete prohibition. Therefore, the difference between the gross surplus in the latter case and that in the former case may be negative:

However, summing both effects, (24) and (25), reveals that the difference is necessarily positive: \(3 (\bar{\theta }+ G)^2/\left\{ 8(2\mu _j-1)\right\} ^2>0\). Moreover, in the case of a prohibition on advertising, there is an additional cost to the third-party producers (\(b\)), which disappears under the complete strategy prohibition. Thus, it is concluded that welfare in complete prohibition is necessarily greater than that in partial prohibition.

E: Choice of partial coverage by firm 1 under entry prohibition of third parties

Let us first consider that firm 1 chooses full coverage in the case where (1) entry of third parties is prohibited and (2) firm 1 may run advertising. The consumer whose love of genuineness is zero purchases the genuine product if the price is equal to or less than \(v_1+s\). Thus, when choosing full coverage, the profit function of firm 1 is given by

where subscript fu denotes full coverage. Solving the profit maximization problem, we obtain the equilibrium level of advertising, which is \(\bar{\theta }/\mu _s\). Then, the equilibrium profit is given by

Next, suppose that firm 1 chooses partial coverage in the same case as above. In this case, the FOCs for firm 1 in the second stage are given by (6) and (8) given \(b=0\). The equilibrium profit is given by

where subscript pa denotes partial coverage. From (26) and (27), we obtain that

Thus, firm 1 necessarily chooses partial coverage in the case that (1) entry of third parties is prohibited and (2) firm 1 may run advertising.

Let us turn to the case in which (1) the entry of third parties is prohibited and (2) firm 1 does not run advertising. When firm 1 aims at full coverage, it must set the price equal to \(v_1\). If the price is higher than this value, consumers with a low degree of love of genuineness make no purchases. The total supply is \(\bar{\theta }\), and the profit is \(v_1 \bar{\theta }\). Next, suppose that firm \(1\) chooses partial coverage. Then, the surplus of consumer \(\theta\) is \(u = v_1 - p_1 +\theta\). Therefore, the demand for the genuine product is given by \(x^M_1 = \bar{\theta }+v_1 -p_1\), and the profit of firm \(1\) is given by \(\pi ^M_1 = (p_1 -c_1) \cdot (\bar{\theta }+v_1 -p_1)\). Solving the profit maximization problem, we obtain the equilibrium price and output (See Table 2). Then, the profit at equilibrium is

A comparison of the profit under partial coverage and under full coverage reveals that the former is greater than the latter:

Thus, firm \(1\) necessarily chooses partial coverage in both cases.

F: Details for Proposition 5

From the second-stage market equilibrium values and (18), we obtain that

However,

Thus, the smaller (larger) the value of \(\alpha\), the more likely it is that (19) is negative (positive).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hattori, K., Higashida, K. Who should be regulated: Genuine producers or third parties?. J Econ 138, 249–286 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-022-00808-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-022-00808-5