Abstract

Dietary impacts on health may be one of the oldest concepts in medicine; however, only in recent years have technical advances in mass spectroscopy, gnotobiology, and bacterial sequencing enabled our understanding of human physiology to progress to the point where we can begin to understand how individual dietary components can affect specific illnesses. This review explores the current understanding of the complex interplay between dietary factors and the host microbiome, concentrating on the downstream implications on host immune function and the pathogenesis of disease. We discuss the influence of the gut microbiome on body habitus and explore the primary and secondary effects of diet on enteric microbial community structure. We address the impact of consumption of non-digestible polysaccharides (prebiotics and fiber), choline, carnitine, iron, and fats on host health as mediated by the enteric microbiome. Disease processes emphasized include non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, IBD, and cardiovascular disease/atherosclerosis. The concepts presented in this review have important clinical implications, although more work needs to be done to develop fully and validate potential therapeutic approaches. Specific dietary interventions offer exciting potential for nontoxic, physiologic ways to alter enteric microbial structure and metabolism to benefit the natural history of many intestinal and systemic disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diet has long been considered a primary factor in health; however, with the microbiome revolution of the past decade, we have begun to understand how diet can alter the microbial composition and function of a given host [1]. An appreciation of the role of the host microbial community in mucosal homeostasis and a variety of diseases has developed alongside our understanding of the complexities of the microbiome-host interaction.

Perhaps the best example of the microbiome-host interaction in a disease state is in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which is believed to be the result of an imbalanced reaction between the genetically regulated host immune system and the microbiome, with important environmental influences [2]. Recent advances suggest that the genetic background of the host may influence the host’s microbiome, with a downstream impact on an individual’s susceptibility to develop IBD, and the severity of their disease [3]. In particular, the rise of IBD incidence in Asia as diet and lifestyle have become more Westernized [4] demonstrates the profound effects that the microbiome can have on a patient’s health. Similarly, metagenomic/metaproteomic studies have found that ileal Crohn’s disease (CD) patients have a unique signature in both bacterial and host expression profiles [5].

This review explores the current understanding of interplay between dietary factors and the host microbiome, concentrating on the downstream implications on host immune function and the pathogenesis of disease. In some of these examples, the interplay between all of these various components has not been established. In others, the kinetics of microbial community shifts need further mechanistic exploration to determine whether the change in microbial status is pathogenic, supportive of pathology, or merely a downstream result of a disease state.

This review is divided largely along the lines of the dietary factor being considered; we cover the role of diet on the microbiome and host health as it relates to the consumption of non-digestible polysaccharides (fiber and prebiotics), choline, carnitine, iron, and fats. Disease processes covered include non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), IBD, and cardiovascular disease (CVD)/atherosclerosis. More generally, we also cover the influence of the microbiome on body habitus and explore newly developed concepts of enteric microbial community structure, metagenomics, and metabolic activities. Finally, we provide some general information (Table 1) of our current understanding of diet and the role in human gastrointestinal health—summarizing both the topics covered in this review and more general advances in the field, independent of microbial involvement.

Diet, global microbial communities, and body habitus

Recently, the concept of enterotypes has developed as a means to categorize the microbiomes of large populations of humans. In a study of the fecal metagenomes of individuals from 4 countries across multiple continents, it was proposed that the microbial community structure and molecular functions of a population could be clustered into three distinct categories, or enterotypes [6]. Interestingly, the phylogenic profile of an enterotype was a poor predictor of host physiology, such as body mass index (BMI); however, various genes and functional (metabolic) modules do correlate with host physiology properties such as age and BMI [6]. Subsequent studies have questioned the presence of three broad enterotypes, but the concept of different enteric profiles in human populations is established [7].

How a given microbial community responds to diet, the role of host genetics in supporting microbial community development, and the effects of different bacterial populations and metabolites on a host’s health all still remain to be determined, but the concept of functionally distinct microbial communities in human populations has presented a conceptual focus as the questions are explored [1]. Based on the diet of individuals, Wu et al. found that normal subjects could be divided into two communities using the same classification as Arumugam et al. [6]: a Bacteroides-dominated profile associated with a high saturated fat/animal protein diet, and a Prevotella-predominant group associated with low amounts of saturated fats and animal proteins but a high amount of carbohydrates and simple sugars [8]. This study also found that the Bacteroides enterotype was resistant to switching to a Prevotella profile during a 10-day feeding trial of a low-fat/high-fiber diet, suggesting that only long-term dietary changes are able to influence enteric bacterial community structure [8].

A study looking at global bacterial populations in vegans, vegetarians, and control subjects found that vegans had decreased levels of Bacteroides spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Escherichia coli, and Enterobacteriaceae spp. compared to control patients, with vegans serving as an intermediate population [9]. Another study reported that short-term (5-day) diets stratified into animal-based verses plant-based influenced host microbial composition. Animal-based diets increased the abundance of bile-tolerant organisms such as Alistipes, Bilophila, and Bacteroides, and decreased the level of Firmicutes that metabolize dietary plant polysaccharides such as Roseburia, Eubacterium rectale, and Ruminoccus bromii [10]. Interestingly, shifting to a plant-based diet had little effect on microbial composition over this time frame [10]. However, gnotobiotic murine studies demonstrate very rapid shifts in bacterial gene expression following dietary manipulation [11].

Given the interplay between diet and the host microbiome, the role of the microbiome in obesity has, not surprisingly, been actively explored in recent years [12]. Studies in mice [13] and humans [14] have found that an obese state is marked by shifts in the microbiome, specifically a decrease in bacterial diversity with a marked decrease in the abundance of Bacteroidetes and an increased abundance in either Actinobacteria [14] or Firmicutes [13]; lean subjects were found to have the opposite trend. Study of carbohydrate metabolic profiles in the human subjects showed clustering along the same Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria/Firmicutes profiles as was seen with obesity; subjects with high levels of Bacteroidetes were enriched in bacterial carbohydrate metabolism enzymes, while subjects with high level of Firmicutes demonstrated enrichment in transport systems [14]. This study also demonstrated that while a core microbiome consistent between all subjects (obese and lean) was not present, a core set of metabolic functions in the microbiome could be identified [14]. Interestingly, some of this work in part contradicts later studies which demonstrate that a high fat/protein diet was associated with increased levels of the Bacteroides (a genus of the Bacteroidetes phylum); however, this later study looked at diet, and not end phenotype (lean vs. obese body habitus) [8].

Beyond association studies, functional studies in mice have led to some understanding of how the microbiome can shape body habitus. Germ-free (sterile) mice were found to be resistant to obesity when fed a high-fat diet, mediated by elevated levels of fasting-induced adipose factor (Fiaf) induction of peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor coactivator (Pgc-1alpha) and increased AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) activity [7]. Additionally, the microbiota of ob/ob mice were found to have an increased capacity to harvest energy from the diet. This property was transferable; germ-free lean mice gavaged with an obese-mouse microbiota developed increased total body fat compared to mice colonized with lean-mouse microbiota [15].

Follow-up studies in non-obese and obese Danish individuals confirmed that obese individuals had decreased levels of microbial diversity, but this population had increased levels of the Bacteroidetes phylum [16]. This study also explored genetic diversity of the microbiome as the independent variable, instead of BMI. It was found that, independent of weight/BMI, individuals with low bacterial genetic diversity were found to have higher levels of insulin resistance, higher levels of serum triglycerides, cholesterol, and insulin, as well as elevated inflammatory markers (hsCRP and WBC) [16]. Additionally, low bacterial genetic diversity individuals had a shift in microbiota favoring an increase in inflammatory microbe profiles and a decrease in anti-inflammatory microbes such as F. prausnitzii [17]; even more interestingly, low bacterial-genetic diversity individuals experienced increased weight/BMI gain compared to high diversity individuals, even after controlling for baseline BMI/weight [16]. This difference in weight gain was associated with decreased levels of eight species of bacteria, all but one of which lacked species-specific taxonomic assignment, but all of which were identified as butyrate producers. This work suggests, for the first time, that specific bacterial species could predispose the individual to weight gain, and that differences in the microbiome and bacterial metabolome of obese individuals might be involved in the pathogenesis of obesity, rather than being a consequence of it.

Dietary components also regulate bacterial gene transcription, with bacteria responding to use the available nutrients most optimally. In particular, when gnotobiotic mice were monoassociated with the human organism Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, this microbe was found to express genes involved in glycan metabolism differently in response to either a polysaccharide-rich or simple-sugar diet to use the energy source available to them most efficiently [18]. For example, the simple sugar diet up-regulated glycoside hydrolase, as well as enzymes able to digest host mucus [18]. Mechanistic studies found that α-mannosides induced the hybrid two-component system BT3172, an environmental sensor that also served as a molecular scaffold for the glycolysis enzymes glucose-6-phosphate isomerase and dehydrogenase [19] providing a mechanistic example for a how a dietary component can regulate bacterial metabolism.

To add to the complexity of the microbiome, during the past decade, researchers have begun to explore how viruses, and in particular, bacteriophages, sculpt the microbiome [20]. This work has largely been limited both by our understanding of the microbiome as a whole, and the sequencing and analytical tools available to researchers, which only in recent years have become powerful enough to explore viral metagenomics [20]. Interestingly, in patients, CD is associated with higher mucosal bacteriophage counts, suggesting that the virome may be involved in the dysbiosis seen in IBD [21]. In the last year, studies of Bacteroidales-like phage populations in humans have found that, like their microbial hosts, these phages can also be clustered into viral enterotypes [22], extending the concept of the global microbial structure to the entire microbial content of the gut.

Non-digestible polysaccharides (butyrate production)

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are produced by fermentation of non-digestible carbohydrates by a subset of anaerobic bacteria in the human colon, primarily in the cecum and proximal colon [23]. Fermentable carbohydrates include pectins, hemicelluloses, gums, and prebiotic substances including fructose and galactose-oligosaccharides that are not responsive to mammalian enzymes, but not what we typically think of as dietary fiber, such as cellulose or wheat bran [23, 24]. The SCFAs produced by fermentation of these dietary substrates serve as a vital fuel source for the colonic epithelium and key regulators of immune homeostasis, and serve as the prototypical example of the symbiotic nature between the microbiome and the host in terms of diet and metabolism [23]. Of the SCFAs, butyrate in particular is considered to be the preferred fuel of colonocytes [23, 25].

During intestinal diversions that result from ostomy procedures, patients develop mild inflammation of the distal, diverted colon, known as diversion colitis. Initial trials in humans demonstrated that butyrate enemas for 2–6 weeks were able to treat patients with diversion colitis [26], suggesting that diversion colitis may be the result of an absence of the metabolically vital SCFAs. While a follow-up trial of only 2 weeks of treatment did not recapitulate the results of the initial study [27], more recent studies in rats did replicate the initial findings [28]. In the treatment of ulcerative colitis (UC), butyrate enemas have shown some promise in a subset of patients. Most studies have had positive or largely positive results, with butyrate enemas decreasing rectal inflammation [29–32], particularly in cases of 5-ASA and steroid-refractory disease [33]. While one randomized, prospective study had negative results [34], another had mixed findings, with outcomes trending towards significance, and suggesting that efficacy was tied to the length of exposure to the butyrate enema therapy [35]—mirroring the different results seen in the human studies of diversion colitis.

The mechanisms by which butyrate promotes mucosal health remain to be fully determined. Besides being an important colonic epithelial fuel source [25], it also modulates the immune system in multiple ways. Initial studies using primary human leukocytes found that butyrate inhibits IL-12 production by S. aureus-stimulated human monocytes [36]. The same study also found that in anti-CD3 stimulated monocytes, butyrate enhanced IL-10 and IL-4 secretion, but inhibited IL-2 and IFN-γ release [36], presenting an anti-inflammatory profile for butyrate. Other in vitro studies have found that butyrate inhibits vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1)-mediated leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells [37]. Ex vivo studies in mice found that butyrate suppresses colonic immune activation through Fas-mediated apoptosis of T-cells, including through histone deacetylase (HDAC) 1-dependent Fas up-regulation [38]. This work also provided evidence that butyrate inhibits IFN-γ-mediated inflammatory signaling, particularly through STAT1 and iNOS, and that loss of butyrate signaling induces increased expression of inflammatory genes in mice [38]. Other in vitro findings demonstrate that butyrate inhibits the IFN-γ/STAT1 axis [39], which is important because enhanced activation of STAT1 occurs in CD patients [38, 40]. Human ex vivo studies found that butyrate was able to decrease pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-β, IL-1β, IL-6) mRNA expression as well as TNF secretion in intestinal biopsies and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of CD patients, through inhibition of NF-κB [41]. More recently, studies in murine bone marrow derived macrophages found that n-butyrate was able to inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling through HDAC inhibition, a process independent of toll-like receptor or G-protein-coupled receptor signaling [42]. This effect has also been observed in in vitro rectal carcinoma cell culture experiments [43]. Several recent studies demonstrated that SCFAs augment colonic regulatory T-cells (Treg) populations, an action mediated in part through a SCFA sensing GPCR encoded by the gene Ffar2 [44], and whose downstream signaling involved decreases in specific histone deacetylases and net increases in histone acetylation [44]. Arpila and colleagues showed that both butyrate and proprionate, which share HDAC-modulating activity, but not acetate, promote extrathymic Treg generation through the intronic enhancer CNSI [45]. This observation is supported by other work where butyrate directly induced Treg differentiation in the colon and attenuated onset of experimental colitis [46]. These activities are thought to be mediated through GPM109A receptors, which jointly bind butyrate and niacin [47]. These observations are highly relevant to human IBD, since one group of 17 human Clostridium species that produce butyrate and other SCFA can inhibit experimental colitis [48].

Based on the role of the microbiome in the production of butyrate, work has also been undertaken to determine if patients with IBD have a microbiome that predisposes them to butyrate deficiency. Initial studies found that a subset of patients with IBD had decreased amounts of the phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes [49], the dominant distal gut phyla and known butyrate producers [50, 51]. The butyrate-producing Clostridum Group IV taxa/subphyla was also implicated in IBD dysbiosis [49]. However, this study did not establish if the microbiome shifts were the result of intestinal inflammation, or were a predisposing factor helping lead to the IBD state.

The first individual bacterial species of these phylum associated with IBD was found to be Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a Firmicutes and member of the Clostridium Group IV. Patients with recurrent CD after resection were found at the time of resection exam to have decreased amounts of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a butyrate producer, suggesting that decreased F. prausnitzii may contribute to or be a marker of a dysbiotic state that predisposes a person to IBD [17]. Follow-up studies in mice found that oral administration of live F. prausnitzii or its supernatant was able to ameliorate TNBS-induced colitis in mice, by partially correcting the dysbiotic state of TNBS-colitis and by inhibiting NF-κB and IL-8 activity [17].

Follow-up studies have since confirmed that both CD [52] and UC [53] patients have decreased levels of butyrate producers, in particular, Clostridum Group IV members and specifically F. prausnitzii. In the UC patients, decreased levels of SCFAs (but oddly not butyrate, which only had a trend towards a significant decrease with disease) were also seen, but the decreases observed were not associated with decreases in a specific bacterial species [53]. Disease activity was inversely correlated with the amount of F. prausnitzii present in the patients’ stool [53]. R. hominis, another butyrate-producing Firmicutes, was also found to be decreased in UC patients, with levels inversely correlated with disease activity [53]. Interestingly, even UC patients in remission had decreased levels of SCFA producers of the Clostridium Group IV, regardless of geographic region [54], suggesting that part of host susceptibility to UC may be a genetic background or dietary factors that diminish colonization of intestinal track by butyrate producers.

Outside of IBD, there also appears to be an association between decreased levels of butyrate producers in other diarrheal diseases. C. difficile infection, the most common cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, with over a half million cases of diarrhea in the United States alone each year and a 30-day mortality of 13.8 % [55], is associated with decreased levels of these protective bacteria [52, 56]. Even more interestingly, C. difficile-negative nosocomial diarrhea is also associated with a decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria, suggesting that the overall integrity of the epithelial barrier is dependent on sufficient levels of butyrate in the intestinal tract [56]. In a small study of CD patients, oral butyrate showed promising results inducing remission and improving symptoms [57], suggesting that oral supplementation may be able to overcome the dysbiotic state IBD patients live with.

Choline

Choline is a vital component of cell membranes, typically obtained from red meat and eggs, but which can also be biosynthesized [58, 59]. It is central to lipid metabolism, and plays a role in the synthesis of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) in the liver [58]. Recent studies have implicated deficiencies in choline in the development of NAFLD and enhanced progression to NASH. NAFLD occurs in 20–30 % of the general population, while the prevalence in obese patients is 75–100 % [60, 61]. Although patients with NAFLD remain asymptomatic, 20 % progress to NASH, which results in increased mortality through cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and portal hypertension [62–64].

Mice fed diets deficient in methionine-choline develop a NASH phenotype, and this process was negatively regulated by the NLRP6 and NLRP3 inflammasomes as well as their effector protein IL-18 [63]. This phenotype was associated with changes in the composition of the gut microbiota, specifically, increased amounts of Erysipelotrichi. The enhanced liver inflammation seen in the various knockout strains was transmissible to co-housed WT mice [63]. The enhanced severity in inflammasome-deficient mice was mediated by toll-like receptors 4 and 9 through TNF-α, and enhanced levels of TLR4 and 9 agonists were found in the portal circulation of inflammasome-defective mice also deficient in choline intake, likely as a result of sub-clinical colonic inflammation mediated by CCL5 [63]. Interestingly, some of these same observations have been found in human subjects. Patients fed a diet deficient in choline had increased accumulation of hepatic fat and the most susceptible patients were those with increased amounts Erysipelotrichi and decreased levels of Gammaproteobacteria in their stool at baseline [65].

The genetic background of mice (including SNPs) is an important sculptor of the gut microbiota [58, 66–68]. A comparison study between two inbred mouse strains, one resistant to NAFLD (BALB/c) and one that is susceptible (129S6) when fed a high fat diet, found that the susceptible strain had lower levels of plasma phosphatidylcholine and higher levels of urinary methylamines [69]. These methylamines are produced exclusively by the gut microbiota as a downstream metabolite of choline. Thus, the microbial composition, as determined by host genetics (and environment), alter the downstream bioavailability of a metabolite (choline) with health consequences for the host [69]. A similar effect of genetics on microbiota was also observed in humans; the PEMT polymorphism increases susceptibility to NAFLD through decreased phosphatidylcholine synthesis. In humans on a normal diet, the abnormal PEMT allele was associated with exacerbated NAFLD in patients with increased stool levels of Erysipelotrichi and decreased levels of Gammaproteobacteria [65]. Patients with the normal allele but with the NAFLD-prone microbial composition had lower levels of hepatic steatosis on a normal diet, suggesting that patients with intact phosphatidylcholine synthesis were able to overcome a NAFLD-inducing gut microbial composition while patients with the PEMT polymorphism were not [65].

Interestingly, the aforementioned NLRP6 deficient mice, which show enhanced NASH in the absence of dietary choline, also develop exacerbated colitis in response to DSS through increased CCL5 secretion [70]. This phenotype, like that of the NASH model, is also transmittable through the microbiota to wild-type hosts, as the altered microbiota generated by the NLRP6−/− intestine are responsible for increased CCL5 secretion [70]. Choline has not been implicated in this model, however. Additionally, in the murine IL-10−/− model of spontaneous colitis, which is dependent on the presence of commensal microbiota [71, 72], decreased levels of plasma choline were observed, alongside increased choline in phospholipids typical of inflammatory processes [73]. An increase in the urine concentration of trimethylamine (TMA), a gut microbial metabolite of choline, was also observed in IL-10−/− mice, particularly as disease progressed over time [74], suggesting that the decreased plasma levels of choline in IL-10−/− mice may be the result of increased microbial metabolism of dietary choline. Interestingly, deficiencies in choline are also observed in the colonocytes of patients with active UC when compared to UC patients with quiescent disease [75]. However, the role of choline deficiency in experimental colitis and human IBD remains to be determined.

Enteric bacterial metabolism of choline has also been implicated in CVD and the generation of atherosclerosis. While it has traditionally been thought that saturated fats and red meat were associated with an increased risk of CVD, recent meta-analyses have found no correlation between saturated fat consumption [76] or red meat consumption [77] and CVD; only processed meats were noted to be correlated [77]. In humans, three metabolites of phosphatidylcholine: choline, TMA-N-oxide (TMAO), the human metabolite of bacteria-produced TMA [78]), and betaine, were found to predict CVD in a cohort study [79]. In Apoe−/− atherosclerosis-prone mice, dietary supplementation with choline or TMAO promoted atherosclerosis, which was associated with increased plasma levels of TMAO [79]. These diets were also associated with increased levels of macrophage foam-cells, and increased amounts of expression of the macrophage scavenger receptors CD36 and SR-A1, both of which are implicated in atherosclerosis [79]. Atherosclerosis was positively correlated with increased plasma levels of TMAO, and increased expression of the hepatic enzyme FMO3 that converts TMAs to TMAOs [79]. Because choline produces TMAOs through the bacteria-metabolite intermediate TMAs, the authors hypothesized that the microbiome played a central role in driving choline-induced atherosclerosis. Not surprisingly, germ-free mice did not produce increased levels of TMAO when fed a high-choline diet, and antibiotic decrease of resident bacteria reduced plasma levels of TMAO and prevented dietary-choline-induced macrophage foam cell production and atherosclerosis [79].

Interestingly, patients with IBD have an increased risk of CVD, despite having a general lower incidence of traditional risk factors [80–82]. Based on the current literature, microbial choline metabolism may be the missing link explaining this association. IBD has recently been associated with high levels of urine TMA, indicating increased choline metabolism [73–75] and decreased choline bio-availability. Similarly, increased levels of the downstream metabolite of TMA, TMAO, is associated with increased atherosclerosis [79]. This suggests that the dysbiosis associated with IBD may define a microbiome that favors choline metabolism, decreasing choline bioavailability and increasing downstream atherosclerotic metabolites.

Carnitine

The role of dietary carnitine in the development of atherosclerosis appears very similar to that of choline. l-carnitine is an abundant nutrient in red meat, which like choline, is processed by the enteric microbiota into TMAs [83, 84]. In a recent study using the same metabolomics data set analyzed in the choline study [79], plasma levels of l-carnitine were also associated with CVD [83]. Using a radio-labeled l-carnitine challenge test, Koeth et al. found that broad spectrum antibiotics diminished the metabolic conversion of l-carnitine to the pro-atherosclerotic metabolite TMAO [83], indicating a vital role for the microbiome in carnitine-associated atherosclerosis. Furthermore, they found that vegans and vegetarians had lower levels of plasma carnitine and a markedly reduced capacity to synthesize TMAO after a carnitine challenge. These differences in ability to metabolize l-carnitine, as measured by TMAO levels, were associated with several microbial taxa. Additionally, using the aforementioned enterotype classification [6], the Prevotella enterotype was associated with higher plasma levels of TMAO than the Bacteroides enterotype [83]. Germ-free and antibiotic administration studies in mice confirmed that intestinal microbial metabolism of carnitine to TMA is central to carnitine-enhanced atherosclerosis, and follow-up studies in an independent cohort of human patients found a dose-dependent relationship between plasma carnitine levels and CVD [83]. Mechanistically, increased levels of TMAOs were associated with decreased levels of reverse cholesterol transport, through alterations at multiple sites of the bile acid synthetic pathway [79, 83].

Dietary and supplemental iron

Iron supplementation serves as a prototypical example of the newly discovered complex interactions between diet, the host immune system, and the gut microbiome, which has downstream consequences for gut homeostasis and health. Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia worldwide, and oral iron supplementation is commonly prescribed for patients diagnosed with anemia [85]. Many patients with IBD have iron deficiency anemia, in addition to frequent anemia of chronic disease, and are consequently given oral and/or parenteral iron supplementation as part of their treatment course [86, 87]. Clinically, it has long been observed that oral iron supplementation is poorly tolerated by some IBD patients, and anecdotally there were some concerns that symptoms of IBD patients worsened while on oral iron therapy [88, 89]. Iron is a known pro-oxidative agent, raising concern that oral iron may increase oxidative stress in patients with colitis as a mechanism of exacerbating disease [90].

Because of these concerns, rodent studies have examined the interplay between intestinal inflammation and iron supplementation. Initial studies in both an iodoacetamide rat model of colitis [90] and in a DSS murine model of colitis [91] demonstrated that oral ferrous sulfate administration exacerbated disease. Initial mechanistic studies suggested that iron supplementation increased tissue oxidative stress [90], perhaps through increased tissue iron deposition [91]. Follow-up in vitro studies in a human colonic tumor cell line supported the hypothesis that iron supplementation enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, which could lead to increased tissue damage [92]. Proteomic analysis of the effects of iron supplementation in the TNFΔARE/WT model of spontaneous, chronic ileitis (driven by overproduction of TNF) demonstrated that iron supplementation exacerbated disease through contrarily regulated proteins involved in energy homeostasis, host defense, and oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress responses [67]. These proteins were aconitase 2, catalase, intelectin 1, and fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (FAH) [67].

Dysfunction of the unfolded protein response (UPR) and downstream autophagic processes as a result of ER stress has been implicated in the pathogenesis of human IBD [93]. Dysfunction of XBP1 protein in mice [94], as well as the downstream UPR effector ATF6 in both mice [95] and zebrafish [96], appear to be involved in the pathogenesis of colitis. One of the key drivers of ER stress in enterocytes is bacterial signaling and translocation across the epithelial barrier [97]. The IBD-susceptibility gene ATG16L1 in combination with murine norovirus infection has been reported to alter Paneth cell function, and is also important for autophagy, the primary response to ER stress [98]. Paneth cells generate numerous antimicrobial peptides and are fundamental to shaping the gut microbial environment [97]. Similarly, NOD2, an intracellular bacterial sensor protein, is also a known IBD-susceptibility gene, with dysfunctional mutations leading to defects in autophagy and resulting intestinal inflammation [97, 99, 100]. Interestingly, oral iron seems to alter these same ER stress/UPR pathways found to be critical in IBD pathogenesis. In the TNFΔARE/WT model of chronic ileitis, oral, but not parental iron, exacerbated disease and enhanced downstream UPR and apoptotic signaling [101]. While oral iron deprivation did not alter T-cell numbers or function, it appeared to sensitize epithelial cells to T-cell (CD8αβ+)-induced apoptosis [101]. Additionally, the lack of oral iron intake in mice altered the microbial composition of both WT and TNFΔARE/WT mice in a similar fashion, independent of the presence of inflammation [101]. Interestingly, while composition was altered, the lack of oral iron intake did not result in changes to overall microbial diversity as measured by the Shannon’s diversity index, nor the number of total operational taxonomic units [101].

Together, these studies suggest that oral iron intake alters gut microbial composition and perhaps function. These alterations either alone or in parallel with direct induction of ROS by iron lead to increased cell stress in enterocytes with subsequent sensitization to inflammatory damage. Thus, during an acute IBD flare, additional of oral iron, which is commonly prescribed today, may actually exacerbate disease. Based on this body of work, parental iron should be considered for actively flaring IBD patients, with oral supplementation (which is slow to replete iron reserves in any case) used when a patient’s disease is quiescent.

Fat

A landmark study recently evaluated the influence of milk fat on the microbiome in murine colitis. Wild-type mice fed a high fat diet comprising either saturated milk fat (MF diet) or polyunsaturated safflower oil fat (PUFA diet) had higher abundances of the Bacteroidetes phylum and decreased levels of Firmicutes, while mice fed a low-fat diet (LF diet) showed the opposite pattern [102]. This pattern mirrored that of the enterotypes seen in human dietary studies [8]. Interestingly, in both the IL-10−/− and DSS models of colitis, the MF diet, but not the PUFA diet, exacerbated disease [102]. This was associated with an increase in Bilophila wadsworthia, a sulfite-reducing bacteria that produces H2S, a substance known to drive T-cell activation and increase gut permeability, and which has been implicated as a bacterial toxin in UC [102–104]. In this work, mono-association studies with germ-free mice demonstrated that milk fat was needed to support colonization of B. wadsworthia, and that this specific bacteria was colitogenic, through induction of a TH1 immune response involving IFN-γ and IL12 production [102]. Production of taurine-conjugated bile acids (taurocholic acids), a preferred fuel source of B. wadsworthia [105], is driven by the consumption of hydrophobic fats such as present in the MF diet [106], and was found to be the key metabolite supporting the bloom of B. wadsworthia in these studies [102]. This study may explain some of the observations in the 1960s that milk consumption was inversely correlated with disease activity in UC patients [107] and increased milk protein antibodies [108], but that follow-up studies exploring the presence of milk allergy as an etiology for IBD were largely negative [109]. Additionally, B. wadsworthia levels were increased in the animal-based, short-term diet study [10], providing evidence that high-fat diets can induce similar changes in microbial changes in humans to those seen in mice. However, the pathogenicity of B. wadsworthia in human IBD remains to be explored.

Not all fat is harmful, however. In mice n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAS, commonly known as omega-3 fatty acids) enhance 5-ASA-mediated recovery from TNBS-colitis [110], reduce obesity-associated Th17 inflammation during TNBS-colitis [111], reduce cytokine production and disease severity in T-cell transfer colitis [112], and reduce Th17 cell populations and disease severity in DSS colitis [113]. In contrast, transfats appear to exacerbate DSS colitis through up-regulation of Th17 signaling [114]. Unfortunately, the results in human CD patients have been more mixed, with conflicting studies finding that omega-3 fatty acids either decreased the rate of relapse [115], or had no effect on the remission rate [116].

Clinical implications

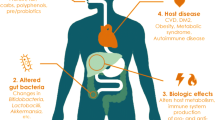

The hope of impacting health through diet may be one of the oldest concepts in medicine; however, only in recent years has our understanding of human physiology grown to the point where we can begin to understand how individual dietary components affect specific illnesses (Fig. 1). In particular, we have begun to understand how the host microbiome, often through complex interplays with the immune system, serves as a central mediating axis in this process. The data presented in this review have important potential clinical implications (Fig. 1), although more work needs to be done to validate the following conclusions and to develop potential therapeutic approaches fully .

The complex interplay of dietary elements, the microbiota, and the host can be beneficial or detrimental to host health. Milk fat (blue): Increased consumption of milk fat leads to increased levels of taurine-conjugated bile acids, which result in a bloom of Bilophila wadsworthia, a colitogenic H2S-producing bacteria. Fiber (pink): Consumption of fiber leads to the production of butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids by colonic bacteria. These SCFAs promote epithelial healing and decrease intestinal inflammation, in part through induction of Tregs. Choline/carnitine (green): Dysbiotic states, as found naturally in a subset of patients or in patients with IBD, results in the increased bacterial metabolism of choline and/or carnitine to TMA. This decreases the bioavailability of choline, leading to NAFLD/NASH, while increased levels of TMA are metabolized by the liver to TMAO, an atherosclerotic compound. Iron (black): Increased oral iron intake is associated with increased intestinal epithelial cell stress and cell death and altered microbiota profiles, which may exacerbate active IBD

IBD patients frequently identify dietary components as triggers of increased symptoms and, therefore, may adopt rather rigid dietary preferences based on their individual experiences [117]. These empiric observations, however, are unique to individuals and need to be more thoroughly investigated by integrated studies of the intestinal microbiome, metagenome, and metabolome. Significant mechanistic advances have been made regarding iron [67, 90, 91, 101] and milk fat [102] in animal models of colitis and ileitis, providing for the first time experimental evidence to back up long-discussed anecdotal observations of diet and IBD. Many IBD patients empirically adopt dairy-free diets [117], but it is not clear whether this is due to lactose deficiency, milk protein allergy, or intolerance of other milk components. A new insight is provided by the observation that milk fat can induce colitis in genetically susceptible IL-10 deficient mice by selectively altering bile acid profiles and stimulating expansion of a rare anaerobic bacteria, B. wadsworthia [102]. Future studies should target these bile acid and bacterial profiles in human studies, particularly comparing milk-tolerant and -intolerant IBD patients. Oral iron can be inflammatory at doses relevant to Western diets and supplements prescribed to patients [67, 90, 91, 101]. Many IBD patients are anemic and are given therapeutic iron, often during a flare, with improved quality of life after improving hemoglobin levels [118]. Although some clinical studies indicate better clinical tolerance with intravenous (i.v.) compared to oral iron supplementation [88], this is not universally supported [87] and the majority of clinicians continue to use oral iron supplementation, although the use of i.v. iron therapy is increasing in some but not all locations [119, 120]. This important clinical issue needs to be resolved with a more comprehensive analysis of the microbiome and fecal metabolome in those patients tolerant vs. intolerant to oral iron therapy to determine a predictive model of optimal supplementation.

IBD patients also frequently include red meats on their list of food intolerances [117]. Whether this perceived intolerance is due to the presence of fats, iron, l-carnitine or other components is unknown. The microbiome-metabolite TMA, which appears to drive diverse inflammatory pathologies, ranging from IBD [73–75] to atherosclerosis [79, 83], through the host-produced TMA metabolite TMAO. Dietary consumption of phosphatidylcholine and l-carnitine provide substrates for resident enteric bacterial metabolism to TMA, which is then converted in the liver to TMAO. The processes involved in establishing and maintaining a high-TMA-producing microbiome remain to be determined, but host genetics appear to be a contributing factor [75, 79, 83]. Elegant animal and human studies have defined this pathway in atherosclerosis [79, 83]. Further studies should target specific microbial targets to block this metabolic conversion, in parallel with dietary intervention studies. Outside of atherosclerosis and IBD, selective choline supplementation may be helpful in patients with NAFLD/NASH. Similarly, once more is understood about the specific microbes that convert choline/carnitine into TMA, targeted antibiotic therapy could be used to decrease these organisms. Doing so would help to both prevent NAFLD/NASH and the atherosclerosis resulting from UC dysbiosis, as the liver would receive more beneficial dietary choline while simultaneously decreasing the production of atherosclerotic TMA.

While TMA is an example of a harmful bacterial metabolite, other protective metabolites produced by a subset of enteric microbiota, including groups IV and XIVA Clostridium species and F. prausnitzii [49, 52, 53, 56], are reproducibly decreased in IBD and many other inflammatory disorders, and serve as potential therapeutic candidates. These bacteria metabolize nondigestible dietary carbohydrate (fibers, prebiotics) to SCFAs. SCFAs, in particular, butyrate, have multifaceted protective properties that include inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines through HDAC activity, inducing regulatory Treg, and stimulating colonic epithelial restitution [23, 25, 28, 30–35, 41, 45–50, 52–54, 57]. The volatility and instability of SCFAs limit their direct therapeutic application. However, indirect approaches such as restoring luminal concentrations and biologic activity of protective bacterial subsets by novel probiotics using depleted resident species [17, 48] and dietary substrates such as prebiotics and fiber have considerable nontoxic, physiology potential. In addition, there are other factors, such as omega-3 fatty acids [111–113], retinoic acid, vitamins A, C, D, and E, which function independent of the microbiome and show some therapeutic benefits, and which could be used as an adjunctive anti-inflammatory agent in patients with IBD and atherosclerosis.

Additional areas of very active and productive clinical investigation are interactions between diet and the microbiome in obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome [1, 12]. Obesity is clearly associated with abnormal microbial profiles [10–14], but results are somewhat inconsistent regarding discrete profiles. For example, one study reported that Bacteroides was negatively associated with obesity [14], while another study found the opposite trend [16]. Amounts of the protective bacteria F. prausnitzii [17] were found to be negatively correlated with both IBD [16] and obesity [16]. Together, these works suggest that a pro-inflammatory profile of bacteria predisposes the host to a variety of metabolic and inflammatory processes. However, ambiguity still persists regarding whether a given dysbiosis is merely correlative or an actual causative factor in obesity, particularly regarding the role of Bacteroides in obesity [8, 14, 16]. This may be in part due to the role that nutrient influx plays in shaping a microbiome [15], which varies between obese and lean individuals. Of note, these trends also appear among the elderly, with the more frail elderly having less diverse microbiomes, decreased numbers of SCFA producers and increased levels of inflammatory markers such as CRP and IL-6, [121]. Interestingly, in the elderly, the same trends also appeared when the patients were analyzed by diet, suggesting that changes in nutritional input may be generating the microbial changes, with subsequent downstream health impacts [121]. These observations imply that diet and nutritional status may be a key intervention to help the elderly.

Overall, the microbiome field has undergone a massive revolution in the last decade, with the availability of affordable microbiome-wide genetic sequencing and the expansion of germ-free and gnotobiotic mouse technologies. As we begin to identify the factors that lead to the development of bacterial community structure and function and learn how these microbiota and their metabolism of dietary components shape human health and disease, completely new types of physiologic, nontoxic therapies could develop, focusing on sculpting the diet and microbiome to promote health.

Abbreviations

- CD:

-

Crohn’s disease

- HDCA:

-

Histone deactylases

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel diseases

- IBS:

-

Irritable bowel syndrome

- NAFLD:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH:

-

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- SCFAs:

-

Short-chain fatty acids

- TMA:

-

Trimethyl amine

- TMAO:

-

Trimethyl amine-N-oxide

- UC:

-

Ulcerative colitis

References

Tremaroli V, Backhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. 2012;489(7415):242–9.

Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(2):577–94.

Knights D, Lassen KG, Xavier RJ. Advances in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis: linking host genetics and the microbiome. Gut. 2013;62(10):1505–10.

Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, Wong M, Chow CM, Hui AJ, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):158–65 e2.

Erickson AR, Cantarel BL, Lamendella R, Darzi Y, Mongodin EF, Pan C, et al. Integrated metagenomics/metaproteomics reveals human host-microbiota signatures of Crohn’s disease. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49138.

Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473(7346):174–80.

Backhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(3):979–84.

Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Keilbaugh SA, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334(6052):105–8.

Zimmer J, Lange B, Frick JS, Sauer H, Zimmermann K, Schwiertz A, et al. A vegan or vegetarian diet substantially alters the human colonic faecal microbiota. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66(1):53–60.

David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2013.

Lynch JB, Sonnenburg JL. Prioritization of a plant polysaccharide over a mucus carbohydrate is enforced by a Bacteroides hybrid two-component system. Mol Microbiol. 2012;85(3):478–91.

Fukuda S, Ohno H. Gut microbiome and metabolic diseases. Semin Immunopathol. 2014;36(1):103–14.

Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(31):11070–5.

Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457(7228):480–4.

Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1027–31.

Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, Prifti E, Hildebrand F, Falony G, et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature. 2013;500(7464):541–6.

Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, Lakhdari O, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Gratadoux JJ, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(43):16731–6.

Sonnenburg JL, Xu J, Leip DD, Chen CH, Westover BP, Weatherford J, et al. Glycan foraging in vivo by an intestine-adapted bacterial symbiont. Science. 2005;307(5717):1955–9.

Sonnenburg ED, Sonnenburg JL, Manchester JK, Hansen EE, Chiang HC, Gordon JI. A hybrid two-component system protein of a prominent human gut symbiont couples glycan sensing in vivo to carbohydrate metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(23):8834–9.

Reyes A, Semenkovich NP, Whiteson K, Rohwer F, Gordon JI. Going viral: next-generation sequencing applied to phage populations in the human gut. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10(9):607–17.

Lepage P, Colombet J, Marteau P, Sime-Ngando T, Dore J, Leclerc M. Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease: a role for bacteriophages? Gut. 2008;57(3):424–5.

Ogilvie LA, Bowler LD, Caplin J, Dedi C, Diston D, Cheek E, et al. Genome signature-based dissection of human gut metagenomes to extract subliminal viral sequences. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2420.

Wong JM, de Souza R, Kendall CW, Emam A, Jenkins DJ. Colonic health: fermentation and short chain fatty acids. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(3):235–43.

Cummings JH, Macfarlane GT. The control and consequences of bacterial fermentation in the human colon. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991;70(6):443–59.

Roediger WE. Role of anaerobic bacteria in the metabolic welfare of the colonic mucosa in man. Gut. 1980;21(9):793–8.

Harig JM, Soergel KH, Komorowski RA, Wood CM. Treatment of diversion colitis with short-chain-fatty acid irrigation. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(1):23–8.

Guillemot F, Colombel JF, Neut C, Verplanck N, Lecomte M, Romond C, et al. Treatment of diversion colitis by short-chain fatty acids. Prospective and double-blind study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34(10):861–4.

Pacheco RG, Esposito CC, Muller LC, Castelo-Branco MT, Quintella LP, Chagas VL, et al. Use of butyrate or glutamine in enema solution reduces inflammation and fibrosis in experimental diversion colitis. WJG. 2012;18(32):4278–87.

Breuer RI, Buto SK, Christ ML, Bean J, Vernia P, Paoluzi P, et al. Rectal irrigation with short-chain fatty acids for distal ulcerative colitis. Preliminary report. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36(2):185–7.

Cummings JH. Short-chain fatty acid enemas in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9(2):149–53.

Scheppach W. Treatment of distal ulcerative colitis with short-chain fatty acid enemas. A placebo-controlled trial. German-Austrian SCFA Study Group. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41(11):2254–9.

Scheppach W, Sommer H, Kirchner T, Paganelli GM, Bartram P, Christl S, et al. Effect of butyrate enemas on the colonic mucosa in distal ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(1):51–6.

Patz J, Jacobsohn WZ, Gottschalk-Sabag S, Zeides S, Braverman DZ. Treatment of refractory distal ulcerative colitis with short chain fatty acid enemas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(4):731–4.

Steinhart AH, Hiruki T, Brzezinski A, Baker JP. Treatment of left-sided ulcerative colitis with butyrate enemas: a controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10(5):729–36.

Breuer RI, Soergel KH, Lashner BA, Christ ML, Hanauer SB, Vanagunas A, et al. Short chain fatty acid rectal irrigation for left-sided ulcerative colitis: a randomised, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 1997;40(4):485–91.

Saemann MD, Bohmig GA, Osterreicher CH, Burtscher H, Parolini O, Diakos C, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of sodium butyrate on human monocytes: potent inhibition of IL-12 and up-regulation of IL-10 production. FASEB J: Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biol. 2000;14(15):2380–2.

Menzel T, Luhrs H, Zirlik S, Schauber J, Kudlich T, Gerke T, et al. Butyrate inhibits leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells via modulation of VCAM-1. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10(2):122–8.

Zimmerman MA, Singh N, Martin PM, Thangaraju M, Ganapathy V, Waller JL, et al. Butyrate suppresses colonic inflammation through HDAC1-dependent Fas upregulation and Fas-mediated apoptosis of T cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302(12):G1405–15.

Klampfer L, Huang J, Sasazuki T, Shirasawa S, Augenlicht L. Inhibition of interferon gamma signaling by the short chain fatty acid butyrate. MCR. 2003;1(11):855–62.

Schreiber S, Rosenstiel P, Hampe J, Nikolaus S, Groessner B, Schottelius A, et al. Activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 1 in human chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2002;51(3):379–85.

Segain JP, de la Raingeard Bletiere D, Bourreille A, Leray V, Gervois N, Rosales C, et al. Butyrate inhibits inflammatory responses through NFkappaB inhibition: implications for Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2000;47(3):397–403.

Chang PV, Hao L, Offermanns S, Medzhitov R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2014.

Waldecker M, Kautenburger T, Daumann H, Busch C, Schrenk D. Inhibition of histone-deacetylase activity by short-chain fatty acids and some polyphenol metabolites formed in the colon. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19(9):587–93.

Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly YM, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341(6145):569–73.

Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, van der Veeken J, deRoos P, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504(7480):451–5.

Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446–50.

Singh N, Gurav A, Sivaprakasam S, Brady E, Padia R, Shi H, et al. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity. 2014;40(1):128–39.

Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, Suda W, Nagano Y, Nishikawa H, et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500(7461):232–6.

Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(34):13780–5.

Mahowald MA, Rey FE, Seedorf H, Turnbaugh PJ, Fulton RS, Wollam A, et al. Characterizing a model human gut microbiota composed of members of its two dominant bacterial phyla. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(14):5859–64.

Thomas F, Hehemann JH, Rebuffet E, Czjzek M, Michel G. Environmental and gut bacteroidetes: the food connection. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:93.

Li E, Hamm CM, Gulati AS, Sartor RB, Chen H, Wu X, et al. Inflammatory bowel diseases phenotype, C. difficile and NOD2 genotype are associated with shifts in human ileum associated microbial composition. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e26284.

Machiels K, Joossens M, Sabino J, De Preter V, Arijs I, Eeckhaut V, et al. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2013.

Rajilic-Stojanovic M, Shanahan F, Guarner F, de Vos WM. Phylogenetic analysis of dysbiosis in ulcerative colitis during remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(3):481–8.

Ananthakrishnan AN. Clostridium difficile infection: epidemiology, risk factors and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8(1):17–26.

Antharam VC, Li EC, Ishmael A, Sharma A, Mai V, Rand KH, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis and depletion of butyrogenic bacteria in Clostridium difficile infection and nosocomial diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(9):2884–92.

Di Sabatino A, Morera R, Ciccocioppo R, Cazzola P, Gotti S, Tinozzi FP, et al. Oral butyrate for mildly to moderately active Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(9):789–94.

Vance DE. Role of phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in the regulation of lipoprotein homeostasis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19(3):229–34.

Zeisel SH, Mar MH, Howe JC, Holden JM. Concentrations of choline-containing compounds and betaine in common foods. J Nutr. 2003;133(5):1302–7.

Ludwig J, Viggiano TR, McGill DB, Oh BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: mayo Clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980;55(7):434–8.

Sheth SG, Gordon FD, Chopra S. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(2):137–45.

Charlton M. Cirrhosis and liver failure in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: molehill or mountain? Hepatology. 2008;47(5):1431–3.

Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Jin C, Hao L, Mehal WZ, Strowig T, et al. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature. 2012;482(7384):179–85.

Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Caldwell SH. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: summary of an AASLD single topic conference. Hepatology. 2003;37(5):1202–19 [Epub 2003/04/30].

Spencer MD, Hamp TJ, Reid RW, Fischer LM, Zeisel SH, Fodor AA. Association between composition of the human gastrointestinal microbiome and development of fatty liver with choline deficiency. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(3):976–86.

Benson AK, Kelly SA, Legge R, Ma F, Low SJ, Kim J, et al. Individuality in gut microbiota composition is a complex polygenic trait shaped by multiple environmental and host genetic factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(44):18933–8.

Werner T, Hoermannsperger G, Schuemann K, Hoelzlwimmer G, Tsuji S, Haller D. Intestinal epithelial cell proteome from wild-type and TNFDeltaARE/WT mice: effect of iron on the development of chronic ileitis. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(7):3252–64.

Gulati AS, Shanahan MT, Arthur JC, Grossniklaus E, von Furstenberg RJ, Kreuk L, et al. Mouse background strain profoundly influences paneth cell function and intestinal microbial composition. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32403.

Dumas ME, Barton RH, Toye A, Cloarec O, Blancher C, Rothwell A, et al. Metabolic profiling reveals a contribution of gut microbiota to fatty liver phenotype in insulin-resistant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(33):12511–6.

Elinav E, Strowig T, Kau AL, Henao-Mejia J, Thaiss CA, Booth CJ, et al. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell. 2011;145(5):745–57.

Karrasch T, Kim J-S, Muhlbauer M, Magness ST, Jobin C. Gnotobiotic IL-10−/−; NF-kappa B(EGFP) mice reveal the critical role of TLR/NF-kappa B signaling in commensal bacteria-induced colitis. J Immunol. 2007;178(10):6522–32.

Sellon RK, Tonkonogy S, Schultz M, Dieleman LA, Grenther W, Balish E, et al. Resident enteric bacteria are necessary for development of spontaneous colitis and immune system activation in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66(11):5224–31 [Epub 1998/10/24].

Martin FP, Rezzi S, Philippe D, Tornier L, Messlik A, Holzlwimmer G, et al. Metabolic assessment of gradual development of moderate experimental colitis in IL-10 deficient mice. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(5):2376–87.

Murdoch TB, Fu H, MacFarlane S, Sydora BC, Fedorak RN, Slupsky CM. Urinary metabolic profiles of inflammatory bowel disease in interleukin-10 gene-deficient mice. Anal Chem. 2008;80(14):5524–31.

Bjerrum JT, Nielsen OH, Hao F, Tang H, Nicholson JK, Wang Y, et al. Metabonomics in ulcerative colitis: diagnostics, biomarker identification, and insight into the pathophysiology. J Proteome Res. 2009;9(2):954–62.

Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM. Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(3):535–46.

Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2010;121(21):2271–83.

Lang DH, Yeung CK, Peter RM, Ibarra C, Gasser R, Itagaki K, et al. Isoform specificity of trimethylamine N-oxygenation by human flavin-containing monooxygenase (FMO) and P450 enzymes: selective catalysis by FMO3. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;56(8):1005–12.

Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472(7341):57–63.

Aloi M, Tromba L, Di Nardo G, Dilillo A, Del Giudice E, Marocchi E, et al. Premature subclinical atherosclerosis in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr. 2012;161(4):589–94 e1.

Rungoe C, Basit S, Ranthe MF, Wohlfahrt J, Langholz E, Jess T. Risk of ischaemic heart disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide Danish cohort study. Gut. 2013;62(5):689–94.

Yarur AJ, Deshpande AR, Pechman DM, Tamariz L, Abreu MT, Sussman DA. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular events. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(4):741–7.

Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, et al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of l-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19(5):576–85.

Rebouche CJ, Seim H. Carnitine metabolism and its regulation in microorganisms and mammals. Annu Rev Nutr. 1998;18:39–61.

Polin V, Coriat R, Perkins G, Dhooge M, Abitbol V, Leblanc S, et al. Iron deficiency: from diagnosis to treatment. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45(10):803–9.

Kulnigg S, Gasche C. Systematic review: managing anaemia in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(11–12):1507–23.

Gisbert JP, Bermejo F, Pajares R, Perez-Calle JL, Rodriguez M, Algaba A, et al. Oral and intravenous iron treatment in inflammatory bowel disease: hematological response and quality of life improvement. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(10):1485–91.

Erichsen K, Ulvik RJ, Nysaeter G, Johansen J, Ostborg J, Berstad A, et al. Oral ferrous fumarate or intravenous iron sucrose for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(9):1058–65.

Lindgren S, Wikman O, Befrits R, Blom H, Eriksson A, Granno C, et al. Intravenous iron sucrose is superior to oral iron sulphate for correcting anaemia and restoring iron stores in IBD patients: a randomized, controlled, evaluator-blind, multicentre study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(7):838–45.

Reifen R, Matas Z, Zeidel L, Berkovitch Z, Bujanover Y. Iron supplementation may aggravate inflammatory status of colitis in a rat model. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45(2):394–7.

Seril DN, Liao J, Ho KL, Warsi A, Yang CS, Yang GY. Dietary iron supplementation enhances DSS-induced colitis and associated colorectal carcinoma development in mice. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(6):1266–78.

Knobel Y, Glei M, Osswald K, Pool-Zobel BL. Ferric iron increases ROS formation, modulates cell growth and enhances genotoxic damage by 4-hydroxynonenal in human colon tumor cells. Toxicol in vitro. 2006;20(6):793–800.

Kaser A, Martinez-Naves E, Blumberg RS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: implications for inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26(4):318–26 [Epub 2010/05/25].

Kaser A, Lee AH, Franke A, Glickman JN, Zeissig S, Tilg H, et al. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008;134(5):743–56 [Epub 2008/09/09].

Brandl K, Rutschmann S, Li X, Du X, Xiao N, Schnabl B, et al. Enhanced sensitivity to DSS colitis caused by a hypomorphic Mbtps1 mutation disrupting the ATF6-driven unfolded protein response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(9):3300–5.

Goldsmith JR, Cocchiaro JL, Rawls JF, Jobin C. Glafenine-induced intestinal injury in zebrafish is ameliorated by mu-opioid signaling via enhancement of Atf6-dependent cellular stress responses. Dis Model Mech. 2012;6(1):146–59 [Epub 2012/08/25].

Kaser A, Blumberg RS. Autophagy, microbial sensing, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and epithelial function in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(6):1738–47 [Epub 2011/05/03].

Cadwell K, Liu JY, Brown SL, Miyoshi H, Loh J, Lennerz JK, et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature. 2008;456(7219):259–63 [Epub 2008/10/14].

Cooney R, Baker J, Brain O, Danis B, Pichulik T, Allan P, et al. NOD2 stimulation induces autophagy in dendritic cells influencing bacterial handling and antigen presentation. Nat Med. 2010;16(1):90–7.

Travassos LH, Carneiro LA, Ramjeet M, Hussey S, Kim YG, Magalhaes JG, et al. Nod1 and Nod2 direct autophagy by recruiting ATG16L1 to the plasma membrane at the site of bacterial entry. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(1):55–62.

Werner T, Wagner SJ, Martinez I, Walter J, Chang JS, Clavel T, et al. Depletion of luminal iron alters the gut microbiota and prevents Crohn’s disease-like ileitis. Gut. 2011;60(3):325–33.

Devkota S, Wang Y, Musch MW, Leone V, Fehlner-Peach H, Nadimpalli A, et al. Dietary-fat-induced taurocholic acid promotes pathobiont expansion and colitis in IL-10−/− mice. Nature. 2012;487(7405):104–8.

Miller TW, Wang EA, Gould S, Stein EV, Kaur S, Lim L, et al. Hydrogen sulfide is an endogenous potentiator of T cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(6):4211–21.

Pitcher MC, Cummings JH. Hydrogen sulphide: a bacterial toxin in ulcerative colitis? Gut. 1996;39(1):1–4.

Laue H, Denger K, Cook AM. Taurine reduction in anaerobic respiration of Bilophila wadsworthia RZATAU. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63(5):2016–21.

Lindstedt S, Avigan J, Goodman DS, Sjovall J, Steinberg D. The effect of dietary fat on the turnover of cholic acid and on the composition of the biliary bile acids in man. J Clin Investig. 1965;44(11):1754–65.

Truelove SC. Ulcerative colitis provoked by milk. Br Med J. 1961;1(5220):154–60.

Taylor KB, Truelove SC. Circulating antibodies to milk proteins in ulcerative colitis. Br Med J. 1961;2(5257):924–9.

Jewell DP, Truelove SC. Circulating antibodies to cow’s milk proteins in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1972;13(10):796–801.

Mbodji K, Charpentier C, Guerin C, Querec C, Bole-Feysot C, Aziz M, et al. Adjunct therapy of n-3 fatty acids to 5-ASA ameliorates inflammatory score and decreases NF-kappaB in rats with TNBS-induced colitis. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24(4):700–5.

Monk JM, Hou TY, Turk HF, Weeks B, Wu C, McMurray DN, et al. Dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) decrease obesity-associated Th17 cell-mediated inflammation during colitis. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49739.

Whiting CV, Bland PW, Tarlton JF. Dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids reduce disease and colonic proinflammatory cytokines in a mouse model of colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11(4):340–9.

Monk JM, Jia Q, Callaway E, Weeks B, Alaniz RC, McMurray DN, et al. Th17 cell accumulation is decreased during chronic experimental colitis by (n-3) PUFA in Fat-1 mice. J Nutr. 2012;142(1):117–24.

Okada Y, Tsuzuki Y, Sato H, Narimatsu K, Hokari R, Kurihara C, et al. Trans fatty acids exacerbate dextran sodium sulphate-induced colitis by promoting the up-regulation of macrophage-derived proinflammatory cytokines involved in T helper 17 cell polarization. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;174(3):459–71.

Belluzzi A, Brignola C, Campieri M, Pera A, Boschi S, Miglioli M. Effect of an enteric-coated fish-oil preparation on relapses in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(24):1557–60.

Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Mittmann U, Bar-Meir S, D’Haens G, Bradette M, et al. Omega-3 free fatty acids for the maintenance of remission in Crohn disease: the EPIC randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2008;299(14):1690–7.

Cohen AB, Lee D, Long MD, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, Sandler RS, et al. Dietary patterns and self-reported associations of diet with symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(5):1322–8.

Gasche C, Dejaco C, Waldhoer T, Tillinger W, Reinisch W, Fueger GF, et al. Intravenous iron and erythropoietin for anemia associated with Crohn disease. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(10):782–7.

Stein J, Bager P, Befrits R, Gasche C, Gudehus M, Lerebours E, et al. Anaemia management in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: routine practice across nine European countries. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(12):1456–63.

Vavricka SR, Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Rogler G, Schwenkglenks M, Achermann R. A shift from oral to intravenous iron supplementation therapy is observed over time in a large swiss cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(4):840–6.

Claesson MJ, Jeffery IB, Conde S, Power SE, O’Connor EM, Cusack S, et al. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature. 2012;488(7410):178–84.

Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2013.

Vazquez-Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, Murray JA, Marietta E, O’Neill J, et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):903–11 e3.

Peery AF, Barrett PR, Park D, Rogers AJ, Galanko JA, Martin CF, et al. A high-fiber diet does not protect against asymptomatic diverticulosis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(2):266–72 e1.

Sharara AI, El-Halabi MM, Mansour NM, Malli A, Ghaith OA, Hashash JG, et al. Alcohol consumption is a risk factor for colonic diverticulosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47(5):420–5.

Catassi C, Kryszak D, Bhatti B, Sturgeon C, Helzlsouer K, Clipp SL, et al. Natural history of celiac disease autoimmunity in a USA cohort followed since 1974. Ann Med. 2010;42(7):530–8.

Acknowledgments

JRG acknowledges support from NIH F30DK085906.

Conflict of interest

Jason R. Goldsmith discloses that he is a technical consultant for Protagonist Therapuetics (Milpitas, CA); R. Balfour Sartor is member of the United States Probiotic Council (Dannon and Yakult Companies).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goldsmith, J.R., Sartor, R.B. The role of diet on intestinal microbiota metabolism: downstream impacts on host immune function and health, and therapeutic implications. J Gastroenterol 49, 785–798 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-014-0953-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-014-0953-z