Abstract

Sedimentary successions exposed at basin margins as a result of late-stage inversion, uplift and erosion usually represent only a limited portion of the entire basin fill; thus, they are highly incomplete records of basin evolution. Small satellite basins, however, might have the potential of recording more complete histories. The late Miocene sedimentary history of the Șimleu Basin, a north-eastern satellite of the vast Pannonian Basin, was investigated through the study of large outcrops and correlative well-logs. A full transgressive–regressive cycle is reconstructed, which formed within a ca. 1 million-year time frame (10.6–9.6 Ma). The transgressive phase is represented by coarse-grained deltas overlain by deep-water lacustrine marls. Onset of the regressive phase is indicated by sandy turbidite lobes and channels, followed by slope shales, and topped by stacked deltaic lobes and fluvial deposits. The deep- to shallow-water sedimentary facies are similar to those deposited in the central, deep part of the Pannonian Basin. The Șimleu Basin is thus a close and almost complete outcrop analogue of the Pannonian Basin’s lacustrine sedimentary record known mainly from subsurface data, such as well-logs, cores and seismic sections from the basin interior. This study demonstrates that deposits of small satellite basins may reflect the whole sequence of processes that shaped the major basin, although at a smaller spatial and temporal scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the late Miocene, the paleogeography and climate of Central Europe was shaped by giant Lake Pannon covering the area between the Alps, Carpathians, and Dinarides (e.g. Kázmér 1990; Bruch et al. 2006). This Caspian-type, endorheic, brackish, and very deep lake and its highly endemic biota emerged at the beginning of the late Miocene when the evolution of the orogenic belts isolated the Pannonian Basin System from the Paratethys Sea (ter Borgh et al. 2013). In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, efforts to understand the paleogeographic evolution of the lake were focused on surface outcrops located in zones where the lacustrine layers were uplifted and eroded due to basin inversion (Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger et al. 2020 and references therein). Beginning from the 1930s, hydrocarbon exploration boreholes revealed that the thickness of the lacustrine and associated deltaic and fluvial sequence attains 5 km in the deepest subbasins. Correlation between the thick basinal successions and the exposed, thin marginal records, however, remained ambiguous until the basin fill geometry was imaged by seismic stratigraphy in the 1980s (Pogácsás 1984; Trkulja and Kirin 1984; Marton 1985; Pogácsás et al. 1988), providing a basis for the first dynamic depositional models (Révész 1980; Bérczi and Phillips 1985; Pogácsás and Révész 1987; Mattick et al. 1988).

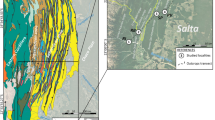

Seismic data revealed that the basin of Lake Pannon was gradually filled with sediments transported by large fluvial systems mostly from the surrounding Alps and Carpathians. The western and central part of the basin was filled by the paleo-Danube system, deriving sediments from the Alps and from the Western Carpathians, whereas sediments into the eastern part of the basin were transported from the Eastern Carpathians and from the Apuseni Mts. mostly by the paleo-Tisza system (Pogácsás 1984; Pogácsás and Révész 1987; Vakarcs et al. 1994; Magyar et al. 2013; Fig. 1A). The spatial and temporal evolution of the paleo-Danube system is relatively well known, and integration of outcrop and subsurface data into uniform sedimentological models was a subject of several studies (e.g. Sacchi et al. 1998; Magyar et al. 2007; Cziczer et al. 2009; Kováč et al. 2011; Sztanó et al. 2013a; Šujan et al. 2016; Sebe et al. 2020). The southwestward sediment transport by the paleo-Tisza and tributaries, however, was studied only in the deep basins of SE Hungary, such as the Derecske Trough (Vakarcs and Várnai 1991; Vakarcs et al. 1994; Lemberkovics et al. 2005; Balázs et al. 2016) and Békés Basin (Teleki et al. 1994; Csató et al. 2015; Fig. 1A). The sedimentary evolution of Lake Pannon in the NE Pannonian Basin in Slovakia, Ukraine, Hungary and Romania remained largely unexplored. Though scattered outcrop data are available from this area, no attempt has been made so far to integrate them into a depositional model, although sedimentary processes in this part of the Pannonian Basin played a key role in the early evolution of the lake.

The objective of this paper is the reconstruction of the sedimentary history of the Șimleu Basin, a northeastern peripheral depression of the Pannonian Basin in Romania, and a better understanding of its contribution to the large-scale evolution of Lake Pannon. We conducted field work and collected well data in and around the Șimleu Basin to identify the major elements of the sedimentary system, the direction of sediment transport, and timing of the processes. By establishing correlation between this basin and the central, deep Derecske Trough, we explored the spatial and temporal relationship between sedimentary processes in a marginal and in a central depression of the same source-to-sink system.

Geological setting

The development of the Pannonian Basin System is coeval with that of the surrounding Carpathian orogenic belt (Horváth et al. 2006). The opening of deep subbasins, controlled by low-angle normal faults and strike-slip faults, was related to the back-arc extension and rotation of blocks (Horváth and Royden 1981; Fodor et al. 1999; Cloetingh et al. 2005; Horváth et al. 2015; Matenco et al. 2016). Extensional deformation during the late early and early late Miocene caused the migration of depocenters in space and time (Horváth et al. 2006; Balázs et al. 2016), and it was followed by a similar shift in the formation of inversion-related structures (Bada et al. 2007). In contrast, the late Neogene evolution of the Transylvanian Basin was controlled by compressional structures, gravitational tectonics over mid-Miocene salt, and salt diapir development (Ciulavu et al. 2002; Krézsek and Bally 2006; Tiliţă et al. 2013).

The tectonic events triggered substantial paleogeographic re-organization on the surface. During the middle Miocene, the Pannonian Basin System was part of the large, inland Paratethys Sea. The uplift of the surrounding orogenic belt isolated the basin from the sea at the beginning of the late Miocene, and a large lake was formed (Rögl 1999; Magyar et al. 1999a; ter Borgh et al. 2013). The brackish-water Lake Pannon, characterized by an endemic biota, covered the Pannonian Basin System from the Vienna Basin in the west to the Transylvanian Basin in the east, encompassing an area of ca. 230,000 km2 (Neubauer et al. 2016). During the first few million years of its geological history, the lake had a highly articulated shoreline with many islands and peninsulas. Most of them were later flooded and eventually buried under sediments as river deltas advanced into the lake basin from the surrounding orogen.

The Şimleu Basin (Fig. 1) is located between the central Pannonian Basin and the Transylvanian Basin. Geographically, it is bounded by the Plopiș and Meseș Mts. in the SW and SE, respectively, whereas its rolling hills pass into the flat landscape of the Great Hungarian Plain towards the E and NE (Fig. 1B). The present topography has a relatively high altitude of 120–320 m above the level of the Great Hungarian Plain as a consequence of the lithospheric-scale uplift of the Transylvanian Basin (Krézsek and Bally 2006; Tiliţă et al. 2013).

The evolution of the Şimleu Basin started with middle Miocene (Badenian) extension, resulting in deposition of foraminifera-bearing deep-water grey marls, while the overlying shallow-marine carbonates and siliciclastics represent the onset of post-rift subsidence. The marine sedimentary record is intercalated with felsic tuffs dated to 14.8–15.1 Ma (Szakács et al. 2012). The upper middle Miocene (Sarmatian) brackish-water deposits attain considerable thickness in some parts of the Şimleu Basin (Nicorici 1972; Clichici 1973). A short-term compressional event led to uplift and subaerial exposure, thus the upper Miocene (Pannonian) lacustrine deposits overlie unconformably on Sarmatian or crystalline basement rocks. As neotectonic uplift is still ongoing, the landscape is changing quickly; hence, landslides detaching in Pannonian clays often create new outcrops and cover up older ones.

Materials and methods

Standard field observations, wireline log interpretation, and biostratigraphic correlation were integrated into a basin-scale stratigraphic and sedimentary model. More than 20 outcrops were measured, and the facies were interpreted in terms of depositional processes (Table 1). The facies were grouped into facies associations to unravel architectural elements of the depositional systems (Table 2). Wireline logs (typically old-vintage GR, SP, and resistivity) from eight wells were digitized and sedimentologically interpreted. Characteristic log shapes of the typical Pannonian basin-fill formations were recognized (e.g. Juhász 1994; Pigott and Radivojević 2010; Sztanó et al. 2016). Finally, outcrop and well data from the Şimleu Basin were correlated through seismic profiles to the Der-I well in the central, deep Derecske Trough of the Pannonian Basin.

Fifteen samples of fossil molluscs were collected from eight outcrops, and the archive collection of the Paleontology-Stratigraphy Museum of the Babeş-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca (BBU) from three localities was also studied. The 43 identified taxa are summarized in Supplement 2. Micropaleontological samples were processed with hydrogen peroxide from about 250 g of air-dried sediments. Twelve samples were barren of ostracods but eleven samples from five outcrops contained ostracod carapaces and single valves, representing 14 taxa (Supplement 3). SEM images were taken at the Botanical Department of the Hungarian Natural History Museum in Budapest.

Facies analysis in outcrops

Facies association 1 (FA1a and FA1b): coarse-grained deltas (Cehei, Porț and Sâg)

Description

FA1 conglomerates show a depositional dip of 10°–20° (Fig. 2). Except for the lowermost boulders, which are made up of Sarmatian carbonates, the conglomerates in Cehei and Porț contain more than 95% mica-schist clasts derived from local sources (FA1a). In contrast, conglomerates near Sâg are polymictic with variable types of igneous, metamorphic, and carbonate clasts, thus indicating a larger, lithologically complex source area (FA1b).

In Cehei, FA1a unconformably overlies an erosional surface carved into the metamorphic basement with several meter relief, and it is capped by the horizontal beds of the muddy FA2. FA1a is a mixture of various sandy and gravelly facies units (Tables 1, 2). The most common are 5–20-m thick bed-sets of massive, poorly sorted, imbricated, clast-supported conglomerates (F15), coarse-grained, fossiliferous, pebbly sands (F12), planar and trough cross-stratified sand (F10), and several-cm-thick mudstone interbeds (F02). The bed-sets consist of laterally thinning beds with a thickness of a few decimeter, and dip towards the S–SW. Although there are lenticular units separated by erosional surfaces, most bed-sets show a convex geometry and downlap on older, flat bed-set boundaries or onlap on the slightly inclined ones (F02), revealing the delicate architecture of foreset terminations.

In the Sâg outcrop (FA1b), the steeply inclined foresets are built by gravelly matrix-supported conglomerate (F14) beds that show a depositional dip of 10°–20° to the N–NW and are overlain by less steep beds of pebbly sand, commonly interfingering with trough cross-stratified pebbly sand (F12). The overlying flat, fine-grained sand is characterized by cross- or planar lamination and trough cross-stratification (F06 and F10), and alternates with pebble strings.

Fossils recovered from the pebbly sand (F12) in Cehei include Melanopsis fossilis and Congeria hemiptycha. The fine-grained intercalations (F02) in Cehei and Porț yielded poorly preserved Congeria cf. czjzeki, C. cf. banatica, Paradacna sp., Lymnocardium sp., Melanopsis sp., Gyraulus sp., and moderately or poorly preserved ostracods, such as Amplocypris bacevice (Fig. 3a), A. abscissa, Candona (Thaminocypris) aff. labiata (Fig. 3c), Herpetocyprella hieroglyphica (Fig. 3f), and H. auriculata (Fig. 3g).

Pannonian ostracods from the Şimleu Basin. a Amplocypris bacevice Krstič, 1973, right valve (RV) in lateral view, Cehei, MIK-27; b Amplocypris abscissa (Reuss, 1850), RV in lateral view, Nușfalău, MIK-20; c Candona (Thaminocypris) aff. labiata (Zalányi, 1929), left valve (LV) in lateral view, Cehei, MIK-28; d Candona sp. juv., RV in lateral view, Varsolţ 1, MIK-30; e Cyprideis heterostigma Pokorný, 1952, RV in lateral view, Nușfalău, MIK-20; f Herpetocyprella hieroglyphica (Méhes, 1907), RV in lateral view, Cehei, MIK-28; g Herpetocyprella auriculata (Reuss, 1850), RV in lateral view, Cehei, MIK-28; h Cyprideis pannonica (Méhes, 1908), LV in lateral view, Ip, MIK-13

Interpretation

Debris flows, grain avalanches and grain flows alternated on the steep, gravelly, sandy foresets. Lobe switching resulted in deposition of mudstones, followed by the onlap/downlap of new lobes. Upwards, with decrease of dip angle and on the flat lying topsets, bedload was deposited as small dunes in shallow channels and as downstream migrating bars. This facies association is interpreted as steep front of Gilbert-type deltas and their delta plain (cf. Postma 1990; Nemec 1990; Gawthorpe and Colella 1990).

The Cehei outcrop reveals the toe and lower portion of foresets, which were covered by offshore mudstones when base-level rise outpaced the locally high sediment input. In the Sâg outcrop, the sediment transport mechanism was dominated by traction of bed-load, evidenced by the dm-scale trough cross-stratification and the low-angle crude-stratification of gravel and sand. The a(p)a(i)-type imbrication in the gravel indicates mass-flow events (cf. Postma 1990). The interfingering of gravel with cross-stratified and sheet-like sands demonstrates the lateral variability of the mouth bars near the topset-foreset transitional zone. Upper-flow regime structures and erosional surfaces point to the effect of occasional floods. Unidirectional currents created shallow channel-form architecture. Wave-induced ripples also occur in this shallow-water topset environment.

The foresets of the Sâg Gilbert-type delta and the channel-fill sediments show the same transport direction towards the N–NW. Based on the progradational directions and the mixed composition of the clasts, the sediment source was in the S–SE, in Plopiș Mts.

The Porț and Cehei outcrops show a slightly different depositional setting. The moderately sorted monomictic gravelly bed-sets in Cehei show convex downlapping geometry and can be interpreted as a lower segment of deltaic lobes, below wave-base, near the foreset-bottomset transitional zone. In Porț, the pebbly sand and massive graded pebbly sandstone of the delta slope might have been transported by short-distance gravity-flows initiated by fluctuating discharge and sediment charge of the feeding local fluvial systems (Gobo et al. 2015).

Fossils of the littoral dwellers Melanopsis fossilis and Congeria hemiptycha (e.g. Pavlović 1928) in the sand of the Cehei outcrop were probably reworked from the eroded topsets. The molluscs and ostracods of the clay-rich intercalations indicate a sublittoral environment with low-energy conditions (e.g. Cziczer et al. 2009). These deposits formed by fallout from suspension and capture periods when active transport occurred on other lobes in laterally offset positions.

Facies association 2 (FA2): open-water lacustrine marls (Varșolț and Cehei)

Description

FA2 is dominated by mudstones (F01). In the uppermost part of the Cehei outcrop, bioturbated and laminated clay overlays the FA1a gravels (Fig. 2B).

A more than 40-m-thick succession of FA2 is exposed in the Varșolț claypit (Fig. 4), where neither the under- nor the overlaying beds are exposed. It consists of brownish-grey, cm-thick, laminated or bluish grey, structureless clay beds (F01), which contain mm-thick silt and up to 20 cm-thick very fine sandstone intercalations (F02, F03, F07, F09) with erosional base, normal gradation and planar- to cross-lamination. Sharp-top sandstone intercalations and rare clay-filled vertical burrows of mm size also occur. The frequency and thickness of silty-sandy interbeds increase upwards (Fig. 4A, B). The paleocurrent directions measured from ripples indicate a NW–SW sediment transport.

The 40 m thick succession of the Varșolț clay pit. A Panoramic view of the mine, with indication of the paleontological samples. The frequency of silty-sandy interbeds, as well as the thickness of these beds increases upwards. : Close view of the marl with an intercalated sand layer. C Medium-bedded turbidites, associated with bioturbated mudstone. Tab and Tad: recognized Bouma-sequences. D Laminated mudstone

FA2 in Varșolț contains a low abundance and poorly preserved mollusc assemblage consisting of thin-shelled forms, such as Congeria banatica (Fig. 5g), C. cf. czjzeki, Lymnocardium winkleri, Paradacna syrmiense, Gyraulus praeponticus, Orygoceras fuchsi (Fig. 5j), Micromelania striata and Socenia acicula. Micropaleontological samples from the Vârșolț claypit yielded mostly thin-shelled, juvenile ostracods and some broken, smooth adult valves belonging to Amnicythere sp., Amplocypris sp., and Candona sp. (Fig. 3d). The Cehei sample contained Amplocypris abscissa, Candona (Thaminocypris) sp., and Herpetocyprella sp.

Pannonian molluscs from the Şimleu Basin. a Lymnocardium cf. schedelianum (Fuchs, 1870), Nușfalău, MAK-19; b Lymnocardium edlaueri Papp, 1953, Nușfalău, MAK-19; c Lymnocardium hantkeni (Fuchs, 1870), Nușfalău, MAK-19; d Lymnocardium conjungens (M. Hörnes, 1862), Nușfalău, MAK-19; e Congeria simulans Brusina, 1893, Nușfalău, MAK-19; f Dreissena auricularis (Fuchs, 1870), Nușfalău, MAK-19; g Congeria banatica R. Hörnes, 1875, Varșolț 2, MAK-41; h Congeria hemiptycha Brusina, 1902, Nușfalău, MAK-19; i Melanopsis vindobonensis Fuchs, 1870 (transitional form to “M. vindobonensis karagacensis” Pavlović, 1927), Nușfalău, MAK-19; j Orygoceras fuchsi (Kittl, 1886, Varșolț 1, MAK-30; k Pseudunio flabellatiformis (Grigorovich-Beresovsky, 1915), Derșida, BBU #15.249

Interpretation

Based on the sedimentary facies, FA2 was deposited relatively far from the sediment supply system, where deposition was mostly related to suspension fallout. The offshore mudstones in the upper part of the Cehei outcrop were formed when base-level rise outpaced the locally high sediment input, thus transgression of the shores resulted in the full flooding of the local island.

The clayey succession at Varșolţ points to different events. The laminated character of the clay, as well as the low abundance of molluscs and ostracods indicate alternations of dysoxic and aerated bottom conditions. The mollusc fauna consists of species that were adapted to the profundal habitats of Lake Pannon (e.g. Geary et al. 2000). The dominance of early juvenile ostracod specimens over adult ones is commonly observed in profundal zones of recent lakes, due to the high mortality rate of instars, transported from the shallower region, under the cold, temporarily oxygen-depleted bottom water conditions (Zhai et al. 2015).

The thin silty to sandy intercalations and the normally graded sand beds are interpreted as products of low-volume, low-density, silty to sandy turbidity currents. Non-gradational sharp-top sandstones may indicate bypassing high-energy turbidity currents. The upward increasing frequency and thickness of the turbidites point to gradual increase of clastic sediment input at the Varșolț section. The continuous sheet-like geometry of the sand beds may reveal either an area very far from distal lobes on the basin floor, or an overbank far from the main slope-channel. The latter option is supported by regional dip observations and the stratigraphic position between outcrops of turbidites and delta-lobes.

Facies association 3 (FA3): turbidite channels and lobes (Panic-N and Panic-S)

Description

FA3 is formed by several-meter-thick successions of sandstones (F09 and F11), conglomerates (F13) and heterolithic alternations of thin sandstones (F03, F07) and mudstones (F01) (Table1). Panic-S and the lower part of Panic-N are sand dominated with a set of related structures, including erosive base, normal gradation, structureless sand containing rip-up mud clasts, horizontal- and cross-lamination, climbing cross-lamination and water-escape structures. Lateral and vertical facies changes are common in the upper part of Panic-N (Fig. 6A–C), consisting of heterolithics (F01, F03), medium-bedded sandstone laterally transforming into thin-bedded sandstone (F07) and matrix-supported mud-clast conglomerates (F13). The sandstones show channel-form geometry: their width varies between 2 and 10 m, while the depth of scouring is up to 1 m. The large (1–40 cm in diameter), rounded to angular, imbricated rip-up mud clasts, floating in medium- to coarse-grained sandstone matrix, are situated above the erosional scours. The mud clasts consist of the heterolithics (F01, F03) and display soft-sediment folding.

Facies association of the Panic outcrops. A Metre-thick-bedded turbidites in the NNW end of the Panic-N outcrop. B Normally graded metre-thick-bedded turbidites in the SSE end of the Panic-N outcrop. C Interpreted panel of sedimentary logs of the outcrop of Panic-N (not to scale) and rose diagram on the measured paleotransport directions. D, E Outcrop of Panic-S. Normally graded meter-thick-bedded turbidites (D) and rip-up mud clasts overlay the erosional scours (E). G Sedimentary log of the Panic-S outcrop

Only a very few, small, indeterminate shell fragments of molluscs and plant remains were found in these sands. Paleocurrent measurements from ripples indicate a westward sediment transport (Fig. 6).

Interpretation

Most facies in the Panic outcrops (F03, F07, F09, F11, and F13) reveal sediment gravity flows. Very thin-, medium- and thick-bedded turbidites, some with Ta, Tcd or Tabcd Bouma-sequences indicate transport by low- and high-density turbidity currents, respectively. As bed thickness decreases, Tcd becomes more common. Thick-bedded mud-clast conglomerates are interpreted as debrites occurring usually not far from the slope (cf. Lowe 1982; Walker 1992; Talling et al. 2012). Low-relief erosional scours, thick, amalgamated, and laterally continuous beds with dewatering structures and climbing ripples indicate rapid accumulation of the sandy sediments, and point to a proximal lobe axis either between channels or in a very shallow aggrading channel. In contrast, the upper part of Panic-N succession is characterized by small yet distinct erosional scours, with a complex channel-fill lithology. The scours were formed by bypassing high-energy erosive currents. High-density currents eroded mud clasts from the previous channel margins or inner levees, and suppressed turbulence led to rapid freezing and deposition (cf. Johnson et al. 2001). The overlying normally graded, medium-bedded turbidites are associated with waning currents (cf. Kneller and Branney 1995). Thin-bedded turbidites indicate the termination of the filling phase. These repeated cut-and-fill successions are interpreted as channel-fill storey elements developed by cyclic waxing and waning flows driven by climate forcing in the endorheic lake (cf. Tőkés et al. 2021).

Taking into account the presence of massive lobate sands associated with scour-fills of mixed origin and internal levees, we assume that the deep-water sediments near Panic were deposited in the proximal part of a turbidite system, probably close to the channel-lobe transitional zone (e.g. Postma et al. 2016; Brooks et al. 2018).

Facies association 4 (FA4): delta front (Nușfalău, Bilghez, Ip, Pericei, Zăuan, Camăr and Sălăjeni)

Description

Deposits of FA4 form 5 to 15 m thick, sand-dominated, coarsening upward successions. In Nușfalău, Pericei and Zăuan, sandstone bed thickness varies between a few centimeters and a few meters, while mudstones are a few dm thick. The fine-grained intervals consist of horizontally laminated silty mudstone (F01) and interbeddings of very fine-grained sand (F02, F04, F06) with abundant small shell fragments and vertical burrows (Fig. 7F). In the overlying, commonly wedge-shaped sandstones, a wide variety of sedimentary facies occur. The thin beds show plane-parallel lamination (F02) and symmetrical and asymmetrical types of cross-lamination (F06) (Fig. 7G), which were formed by rapid flows and wave and current ripples, respectively (Fig. 7E, F). Intensity of bioturbation varies in these beds, from distinct, sand-filled, simple vertical burrows of dm length and cm diameter, through moderate density of burrowing to full homogenization of the sediment. The thick beds show tabular and trough cross-bedding (Fig. 7H) (F08, F10), but structureless, amalgamated, i.e., fully bioturbated beds also occur (Fig. 7F). Small mud clasts, plant debris, and shell fragments are common at the lower part of foresets (Fig. 7D).

The Nușfalău outcrop. A Schematic drawing of the Nușfalău outcrop with a rose diagram showing the measured paleotransport directions. B Two sedimentary logs (I and II, their locations in A) with positions of the paleontological samples. C Panoramic view of the outcrop. D A Congeria hemiptycha specimen in the sand. E–I The observed sedimentary facies (see in text)

The Camăr, Sălăjeni, and Ip outcrops are characterized by thick, tabular and trough cross-bedded, medium-grained sandstones (F08, F10) containing mud clasts and coquinas at their base. These sand bodies display a low-relief channel shape, and interfinger with parallel-laminated fine-grained sand.

Above low-angle erosional surfaces, laterally continuous, parallel-laminated or cross-bedded fine-grained sandstone (F06, F08) bed-sets and thin mud layers with vertical burrows occur at Bilghez.

FA4 contains the most diverse mollusc fauna of all FAs. Common taxa include Congeria hemiptycha (Figs. 5h, 7D), C. simulans (Fig. 5e), Dreissena auricularis (Fig. 5f), Lymnocardium conjungens (Fig. 5d), L. cf. schedelianum (Fig. 5a), L. edlaueri (Fig. 5b), L. hantkeni (Fig. 5c), Melanopsis bouei, M. vindobonensis (Fig. 5l), and small-sized hydrobiid snails. A poor benthic ostracod assemblage with well-preserved valves and carapaces and with more adult than juvenile specimens was recovered in Ip and Nușfalău, with Cyprideis pannonica (Fig. 3h) being present in all samples. Other forms include Amplocypris abscissa (Fig. 3b), Cyprideis heterostigma (Fig. 3e), Amnicythere sp., Candona sp., Herpetocyprella sp., and Loxoconcha sp. juv.

Interpretation

FA4 is the most commonly exposed facies association in the Şimleu Basin (Table 2.). The sand-dominated, coarsening-upward sequences in Nușfalău, Pericei and Zăuan indicate an upward increasing water agitation by currents and waves, reflecting a change from the transitional zone to the foreshore, with the dominance of current-induced structures. The downlapping or wedge-shaped bed-sets with laterally varying thickness indicate lobate geometry, which is typical for the shallow-water mouth-bars of deltas (Martini and Sandrelli 2015). The alternation of thin sandy and muddy beds, associated with different ripples and burrows, indicates the distal/lower delta-front, where the combined effect of waves and river floods prevail (Plink-Björklund and Steel 2004; Carvajal and Steel 2009; Jorissen et al. 2018). The thickening of sand beds reflects delta front progradation as the increasing effect of river discharge (Olariu and Bhattacharya 2006). Sandy successions from erosional scours, coquina or mud-clast accumulations, overlain by thick cross-bedded sandstones represent channels on the mouth bars (cf. Jordan and Pryor 1992; Olariu and Bhattacharya 2006). The effect of waves was more pronounced on the lower delta front than on the upper one, therefore these deltas are classified as river-dominated. Yet, the parallel-laminated, sheet-like sandstones at Bilghez deposited on a high-energy wave-modified bar top (cf. Reading and Collinson 1996; Schomacker et al. 2010), pointing to local variations.

The mollusc fauna of FA4 indicates some variety and patchiness in the depositional environment. The Ip fauna suggests a vegetated nearshore environment based on the dominance of small-sized melanopsids (e.g. Müller and Szónoky 1990). In Nușfalău, Sălăjeni, and Zăuan, higher-energy environment can be inferred from the abundance of the large-sized and thick-shelled molluscs (M. vindobonensis, C. hemiptycha, and L. cf. schedelianum). The Nușfalău fauna also includes Melanopsis with irregular, knobby sculpture, described by Pavlović (1928) from Vrčin, Serbia as M. vindobonensis karagacensis (Fig. 5i). We assume that this unusual pattern is a paleopathological feature rather than an ecological response.

The ostracod genus Cyprideis is known to prefer the littoral zone in marine and lacustrine environments (e.g. Morkhoven 1963; van Harten 1990; Boomer et al. 2005; Beker et al. 2008; Stoica et al. 2013). Its massive, less ornate carapace may reflect adaptation to high-energy bottom water conditions and to the sand-dominated substrate.

Facies association 5 (FA5a and FA5b): lower and upper delta plain (Derna, Cuzap, Șărmășag, and Voivozi)

Description

FA5 is composed of alternating mud- and sand-prone facies, with very thin lignites in FA5a and mineable ones in FA5b. In the central part of the basin, at the outcrops of Nușfalău, Camăr, Bocșa, Șărmășag and Ip, FA5a overlies FA4 and consists of alternating layers of clay (F01), laminated silty sand (F04), and cross-laminated fine-grained sand (F06) with 2–3 mm wide and a few cm long, sand-filled vertical burrows. It comprises a few meter-thick, coarsening upwards units, topped by organic-rich clays or cm-thick lignite seams (F05) (Table 1).

In the open-pit lignite mines of Derna, Voivozi, and Cuzap, FA5b is exposed as 3–10-m thick mudstone-dominated successions (F01) with thick intercalations of cross-bedded, very coarse, pebbly sand (F08, F10) and lignite beds (F05) up to a thickness of 0,5–3 m (Fig. 8). Coalified logs (Fig. 8D) and leaf imprints are well preserved. The sandstones form up to 10’s of metres wide and 2–6 m thick channel-forms or mounds (Fig. 8A). The succession directly overlies the crystalline basement at the NW tip of the Plopiş Mts.

Interpretation

The mudstones with thin sandy interbeds filled the interdistributary bays of the lower delta plain during subsequent floods, resulting in the formation of swamps (Table 2). Thick cross-bedded sands formed as active distributary channel fills, while organic-rich deposits represent abandoned channels, ponds or swamps on the upper delta plain. Distribution of sediments and thickness of lignites on the delta plain was strongly influenced by compaction-related subsidence (cf. Phillips and Bustin 1996; Reading and Collinson 1996).

A specimen of the pearl mussel Pseudunio flabellatiformis from Derna (BBU #15.273) indicates a freshwater-fluvial environment. Lubenescu et al. (1967) reported a small fauna with Tinnyea vasarhelyii and small- and large-sized melanopsids from the Șărmășag locality, suggesting a well-vegetated environment with changing salinity conditions.

Facies association 6 (FA6): fluvial channels (Corund, Derșida, and Cohani)

Description

FA6 is composed of medium- to coarse-grained sandstone and subordinate mud layers. The Cohani outcrop displays a 20–25 m thick succession of laterally discontinuous, trough cross-bedded, coarse-grained sandstone (F10) and tabular cross-bedded sandstone (F08) packages. Thickness of the bed-sets varies between 0.4 and 1.5 m. Above the basal surfaces, imbricated pebbles occur. Some thin-bedded, silty, very fine sand beds (F06) are associated with completely weathered tuff horizons. Pieces of silicified wood fragments also occur. Sandstone series are bounded by major erosional surfaces with a relief of 2 m. Similar cross-bedded sandstone occurs in the small Corund outcrop.

Interpretation

The cross-bedded sets, separated by erosional surfaces, represent vertically and laterally stacked, aggradational multistorey fluvial channel-fills (cf. Collinson 1996). Each storey contains channel-fill bars separated by minor erosional surfaces. The fine-grained sediments are restricted to the bar tops. Mudstones of the surrounding floodplains are not exposed.

Various fossils were reported from Derșida (Paucă 1954; Maxim and Ghiurcă 1960, 1963, 1964; Codrea et al. 2002; Codrea and Margin 2009), but we failed to identify their exact locality in the field. Maxim and Ghiurcă (1960) reported a mixed mollusc fauna, consisting of land (Cepaea), freshwater (Unio, Viviparus, Lithoglyphus, Valvata, Lymnaea, Planorbis, and Planorbarius), and brackish-water (Melanopsis) elements. The BBU material from Derșida (collected and determined by Maxim and Ghiurcă 1960) contains 41 specimens of the fluvial Pseudunio flabellatiformis and an indeterminate Melanopsis species (#15.247–15.272 and 15.274–15.280).

Correlation of facies associations to the subsurface

The depositional systems represented by the exposed facies associations are also recognized in the subsurface. In the Săcueni, Bobota, Mișca, Tăuteu and Chiraleu wells, serrated and blocky log shapes indicate coarse sand and conglomerate of up to 20–50 m thickness, overlying the crystalline basement or middle-Miocene deposits. These correspond to FA1 recognized in outcrops. Elsewhere the lacustrine sedimentary record starts with about 30 m thick offshore marls (FA2).

Above the marls, up to 30 m thick blocky and barrel-shaped sandstone sequences separated by 2–10 m thick mudstones occur in the Zalău, Nușfalău and Săcueni wells. These are interpreted as sand-prone lobes of a turbidite system. The corresponding FA3 in outcrops of Panic show the channel and/or channel-lobe transitional zone.

The overlying, up to 300 m thick unit, being present in all wells of the study area, displays smooth or finely serrated log shapes. It is interpreted as mudstones deposited on the shelf-edge slope (FA2). It thickens to 400–700 m towards the basin interior in the west west (Săcueni, Chiraleu).

Funnel log shapes correspond to 20–50 m thick coarsening upward successions and reveal prograding sandy delta lobes (FA4 and FA5) representing the upper part of the basin fill.

The youngest unit of the upper Miocene lacustrine sequence shows a serrated log pattern interrupted by up to 20-m thick intervals of bell and blocky log shapes. These are interpreted as representing a clayey-silty alluvial plain, cross-cutted by sandy channel-belt deposits (e.g. FA6, Cohani). The thickness of this unit increases to 500 m westwards in the Cheţ and Derecske Troughs (e.g. Chiraleu).

Biostratigraphy and age

Earlier mollusc biostratigraphic studies from the Şimleu Basin correlated the lacustrine succession with the lower part of the Pannonian, stressing that the oldest Pannonian biozones are missing in the area (Matyasovszky 1879; Lubenescu et al. 1967; Marinescu 1985; but see Chivu et al. 1966).

The low-diversity mollusc fauna recovered from the coarse-grained deltas in Cehei is indicative of the Lymnocardium conjungens Zone (11.0–9.6 Ma; Fig. 9). The bivalve Congeria hemiptycha (also known by its junior synonym as Congeria pancici Pavlović 1927) first appears in “Zone D” of the Vienna Basin (Papp 1985), which was dated 10.6–10.4 Ma by Harzhauser et al. (2004). The age of the Cehei conglomerates and sandstones is thus restricted to the interval of 10.6–9.6 Ma (Fig. 9).

State-of-the-art biozonation of Lake Pannon deposits with the age of the studied Pannonian localities of the Șimleu Basin. Mollusc zonation follows Magyar and Geary (2012), ostracod zonation is modified after Krstić (1985). Paleomagnetic chrons and European Neogene mammal biozones are used after Hilgen et al. (2012). Blue line indicates profundal, green sublittoral, red littoral, and purple freshwater-fluvial environment. Turquoise bracket shows the 10.6–9.6 Ma time interval supposed for the main transgressive–regressive cycle in the Șimleu Basin

The profundal fauna of the offshore lacustrine marls (FA2) in Vârșolț belongs to the Congeria banatica Zone (~ 11.45–9.6 Ma; Fig. 9). In an outcrop SE of Nușfalău, Papp (1915) found a well-preserved specimen of Lymnocardium soproniense (“L. penslii”), together with Congeria banatica and C. partschi in “sandy marl” that underlies the fossiliferous deltaic sediments at Nușfalău. This finding indicates the L. soproniense Zone (10.2–8.9 Ma; Magyar et al. 2016; Fig. 9).

Based on the common occurrence of Lymnocardium conjungens, L. hantkeni, Congeria hemiptycha, Melanopsis vindobonensis etc. (see in Lőrenthey 1893; Strausz 1941; Lubenescu et al. 1967; Nicorici and Karácsonyi 1983), the shallow-water lacustrine deltaic sands (FA4 and FA5) belong to the upper part of the Lymnocardium conjungens Zone (ca. 10.2–9.6 Ma; Fig. 9). The appearance of Dreissena auricularis in these assemblages, however, points to the youngest part of this zone. Papp (1950) postulated that D. auricularis evolved from Congeria gitneri, and the stratigraphic distribution of these two species in the western part of the Pannonian Basin is in accord with this hypothesis (Magyar et al. 1999b). The earliest occurrence of D. auricularis in Pezinok (Horusitzky 1907) was dated by mammal stratigraphy as early MN10, ca. 9.6–9.7 Ma (Joniak 2016).

The ostracod Amplocypris abscissa, occurring in FA1 and FA2 in Cehei and in FA4 in Nușfalău, was considered by Krstić (1985) as a biostratigraphic marker of the Amplocypris abscissa and the overlying Hemicytheria croatica zones. A. abscissa occurs in the Hennersdorf outcrop next to Vienna (Danielopol et al. 2011), which was interpreted by Harzhauser et al. (2004) as being 10.2–10.4 Ma old.

The most common fluvial mussel, Pseudunio flabellatiformis, is well-known from the fluvial deposits of the Pannonian Basin throughout the entire late Miocene (as “Unio wetzleri” or “Margaritifera flabellatiformis” in the older literature; here we follow the revision of Lyubas et al. 2019); thus, it does not constrain the age of FA5 and FA6 occurrences. In Derșida and in the lignite-bearing deltaic layers of Derna, however, Anancus arvernensis remains were found (Codrea and Margin 2009; Gasparik pers. comm. 2020). The oldest known European occurrences of this large-sized mastodon are Messinian (MN12, from 7.2 Ma on; Konidaris and Roussiakis 2018). This dating implies a significant stratigraphic gap between the older-than-9.6-Ma lacustrine and the younger-than-7.2-Ma fluvial deposits, but this gap is not supported by our field observations. This contradiction thus remains unresolved until a more detailed study of the unconformities in the area or a revision of the large mammal stratigraphy brings along new perspectives.

Changes of the depositional environment

The oldest lacustrine sediments exposed in the study area are the coarse-grained conglomerates and sandstones, deposited in locally-sourced progradational Gilbert-type deltas that rimmed the islands during the initial flooding of the Șimleu Basin (Fig. 10A). Their age is known only at Cehei (10.6–9.6 Ma), but they could have developed diachronously along the margins.

Late Miocene (10.6–9.6 Ma) basin-fill history of the Șimleu Basin. TRG transgression, REG regression. A Ca. 10.6 Ma ago, Lake Pannon flooded the study area. Some basement blocks became islands and provided sediment for Gilbert deltas. B Transgression created widespread open- and deep lacustrine environment and basement highs were flooded by ca. 10.2 Ma. C Infilling of the basin started from the NE by deposition of turbidite lobes. D The shelf-edge slope prograded from E to W across the Simleu Basin not later than 9.6 Ma ago. E Paleotransport directions based on field data in the Şimleu Basin. F Timing of shelf-edge progradation in Lake Pannon (after Magyar et al. 2013)

The coarse-grained deltas show various paleotransport directions depending on their sources (Fig. 10E). The polymict conglomerates at Sâg confirm that some parts of the Apușeni Mts. (e.g. Plopiș area) were elevated and subaerially exposed during the early late Miocene (Fig. 10A), as Nicorici (1972) and Clichici (1973) postulated formerly. The monomict systems (Cehei) were sourced from inverted metamorphic basement horsts. All these coarse-grained deltas could have been intimately associated with active fault scarps (cf. Colella 1988; Gawthorpe and Colella 1990; Sztanó et al. 2010).

As base-level rose and islands submerged, offshore mudstones were deposited by suspension fallout. These preserved the fossils of the profundal Congeria banatica fauna, which was widespread in Lake Pannon between ca. 11 and 9.6 Ma (e.g. Botka et al. 2019). The low abundance and low diversity of the fauna indicate a partially isolated, oxygen-depleted deep-water environment (Fig. 10B).

The first distally sourced clastics, indicating the onset of regression in the Șimleu Basin, were thin-bedded turbidites in the upper part of the profundal mudstones. The coeval slope might have prograded from E or SE (Fig. 10B), implying that the Meseș Mts. was not a confining barrier at that time: the central Pannonian Basin and the Transylvanian Basin were geographically connected through the Șimleu Basin.

A more robust evidence of the ESE to WNW advancing slope progradation is provided by the sandy turbidites at Panic, which can be interpreted as lobe axis and/or lobe-channel fill deposits (Fig. 10C). Few 10 s of metre thick stacked turbidite sequences also appear in wells near Zalău, Nușfalău, Bobota, Chiraleu, and Săcueni. The relatively small thickness, coupled with the probably large extent of these sand lobes is typical for unconfined toe-of-slope turbidite systems (cf. Sztanó et al. 2013b; Tőkés and Patacci 2018).

Turbidites are overlain by 200–300-m thick mudstones (Nusfalău and Bobota wells), which can be attributed to the slope. A seismic section from Căuaş, 25 km to the N (Fig. 7 in Ciulavu et al. 2002), displays ca. 150 m high clinoforms. Progradation of similar, relatively small clinoforms might have filled the Şimleu Basin rapidly. The advance of the shelf-edge was supplied by river-dominated deltas at around 9.7–9.6 Ma. Measurements indicate paleotransport directions to WNW and NW, i.e. towards the central parts of Lake Pannon (Fig. 10E).

Based on outcrop data, the thickness of individual deltaic parasequences varies between 3 and 10 m, and they build up to 50 m thick deltaic sequences displayed by well-logs. The height of the parasequences and deltaic bodies in the Șimleu Basin is in the same range as in the paleo-Danube or paleo-Tisza systems (Juhász 1994; Sztanó et al. 2013a; Magyar et al. 2019). These packages indicate moderate-amplitude short-term base-level changes and/or autocyclic avulsions of the feeding rivers.

Correlation and comparison with the central Pannonian Basin

Both the eastern part of the deep, central Pannonian Basin and the Şimleu Basin were filled by sediments derived from the Eastern Carpathians. Their evolution was parallel, but infill of the Pannonian Basin lasted for ca. 7 million years (Magyar et al. 2013), while that of the Şimleu Basin took only less than 1 million years. To understand the role that the Şimleu Basin played in the infill of the large system, correlation was established to the Derecske Trough, one of the deepest depocenters of the Pannonian basin ca. 70 km to the W of the Şimleu Basin (Fig. 11).

The base of the Neogene gradually ascends from several hundred meter depth in the Şimleu Basin to more than 5 km in the Derecske Trough. The largest throw is observed at the Suplacu de Barcău fault zone, which played a crucial role in the accumulation of the Suplacu oil field, one of the largest in the Pannonian Basin (e.g. Panait-Patica et al. 2006).

Exploration wells in the region are generally located above the basement highs, such as the Chiraleu and Săcueni highs, whereas the basin interiors are mostly known from seismic data (Fig. 11). The 5200 m deep Derecske-I hydrocarbon exploration well (“Well-5” in Vakarcs et al. 1994) was drilled close to the center, yet the deepest part of the basin was not reached (Balázs et al. 2016).

The late Miocene lacustrine succession in the Derecske-I well (Table 3) starts with deep-water marls. The overlying basin-center confined turbidite system is made up of lobe complexes with paleotransport directions from NE to SW (cf. Sztanó et al. 2013b). These are overlain by slope deposits, i.e. thin unconfined turbidites and monotonous mudstones. The slope related clinoform height is ca. 650 m in the Derecske Trough (Balázs et al. 2018). It decreases to ca. 500 m in the Cheţ and Abrămuţ basins in the east, whereas in the Şimleu Basin it is not higher than 200 m. Considering compaction, the tallest slopes during deposition could have exceeded 1000 m height in the Derecske Trough (Balázs et al. 2018) and 300 m in the Şimleu Basin. Deltaic successions are built up of 30–50 m thick, coarsening-upward lobe cycles. The overlying late Miocene to Quternary fluvial suit is extremely thick in the Derecske Trough. The elements of the lacustrine sedimentary succession are almost identical in the Derecske Trough and Şimleu Basin, except for their thickness and timing.

The clinoforms provide another aspect for comparison. The direction of progradation was from E–SE to W–NW in the Şimleu Basin, as measured in the field within the turbidites and delta sediments. In contrast, in the eastern depocenters of the central Pannonian Basin, on both sides of the Hungarian-Romanian border, slope progradation was from N–NE to S–SW, as evidenced by seismic clinoforms (Tulucan 2007; Răbăgia 2009; Horváth and Pogácsás 1988; Vakarcs et al. 1994; Lemberkovics et al. 2005; Magyar et al. 2013). This pattern indicates a mergence of different fluvial feeder systems immediately W of the Şimleu Basin. Similar features were observed in other parts of the Pannonian Basin as well (Pogácsás and Révész 1987; Magyar et al. 2013).

In an earlier study (Magyar et al 2013), seismic surfaces were calibrated as biozone boundaries across the Pannonian Basin, and they were dated according to the biochronostratigraphic system of Magyar and Geary (2012) (Fig. 9). The 8.6 Ma surface, corresponding to the base of the Lymnocardium decorum Zone, reaches the shelf edge 4 km to the SW of Derecske-I (Fig. 10F). The correlation of this surface towards the Şimleu Basin is straightforward up to the Suplacu fault zone; coeval deposits in the Şimleu Basin, however, have been eroded (Fig. 11). This correlation sets a lower limit (a minimum) on the age of the lacustrine and deltaic succession of the Şimleu Basin. Thus, there is a 1 million-year time shift in the formation of the shelf edge and related facies associations between the Şimleu Basin and Derecske-I well. The shelf-edge advanced across the Şimleu Basin at about 9.7–9.6 Ma, probably in a very restricted time interval (a few 100 kys at most). Between 9.7 and 8.7 Ma, the shelf-edge advanced ca. 70 km to the west, across the Abrămuţ Basin and Cheţ Trough to the Derecske Trough, into increasingly deeper water. This rate is similar to the rates observed in other parts of Lake Pannon (cf. Sztanó et al. 2013b) and in supply-dominated, moderately deep-water marine settings worldwide (Carvajal et al. 2009). The shelf accretion was fed by deltas across the Şimleu Basin (at least up to 9.6 Ma). When delta lobes filled the available accommodation to lake level in the Şimleu area, deposition of turbidites occurred in a water depth somewhat larger than 1000 m in the Derecske Trough. Thus, the late Miocene paleorelief can also be assessed from these data. The roughly estimated sedimentation rates in the studied successions of the Şimleu Basin and in the basin interior are on the same order (Table 3).

The outcrops of the relatively thin Pannonian succession of the Şimleu Basin thus display the whole variety of processes that shaped the Pannonian Basin, including deep-water turbidite and slope formation. This pattern is noteworthy because most Pannonian outcrops expose only a limited segment of the basin fill. The most commonly exposed units are either coarse-grained deltas at the base of the succession (Sztanó et al. 2010; Budai et al. 2019) or deltaic and fluvial deposits (e.g. Kováč et al. 1998, 2018; Sacchi et al. 1998; Uhrin and Sztanó 2007; Sztanó et al. 2013a; Magyar et al. 2017; Pavelić and Kovačić 2018), neither of which represent the full history of basin evolution. Generally, deep-water deposits, such as offshore marls and turbidites, are particularly rare in surface outcrops (Kovačić et al. 2004; Krézsek et al. 2010; Bartha et al. 2015; Tőkés et al. 2021). The Şimleu Basin owes its uniqueness to its paleogeographic position close to the margin of the Pannonian Basin but well within Lake Pannon, to its subsidence and deepening that was mostly coeval with that of the main basin, to its size and topography that allowed the formation of a deep-water environment, and to its early sedimentary infill that took place soon after the onset of normal regression of Lake Pannon.

Conclusion

The upper Miocene facies associations in the Şimleu Basin, a northeastern marginal depression of the Pannonian Basin, represent a major transgressive–regressive cycle deposited in Lake Pannon. The Şimleu Basin is unique, because each important element of a source-to-sink system was present in this relatively small and shallow basin. Fluvial, deltaic, shelf-edge slope, and open-to-deep lacustrine depositional settings were identified in outcrops and shallow boreholes. For instance, coarse-grained deltas, deposited above active fault scarps during the diachronous initial transgression of Lake Pannon, and deep-water turbidites are equally accessible in outcrops. Biochronostratigraphic considerations constrain the age of the lacustrine and deltaic sediments of the Şimleu Basin to 10.6–9.6 Ma. Compared to the upper Miocene succession of the Derecske Trough, an adjacent deep sub-basin of the central Pannonian Basin, the analogous units are an order of magnitude thinner in the Şimleu Basin, yet sedimentation rate was similarly high. Having been located closer to the source, however, the shelf-edge and related facies associations are one million years older in the Şimleu Basin than in the Derecske Trough. Both basins were filled by sediments derived from the Eastern Carpathians, and both funneled them further to the deep basin interior.

References

Bada G, Horváth F, Dövényi P, Szafián P, Windhoffer G, Cloetingh S (2007) Present-day stress field and tectonic inversion in the Pannonian basin. Glob Planet Change 58:165–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2007.01.007

Balázs A, Matenco L, Magyar I, Horváth F, Cloetingh S (2016) The link between tectonics and sedimentation in back-arc basins: new genetic constraints from the analysis of the Pannonian Basin. Tectonics 35:1526–1559. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015TC004109

Balázs A, Magyar I, Matenco L, Sztanó O, Tőkés L, Horváth F (2018) Morphology of a large paleo-lake: analysis of compaction in the Miocene-Quaternary Pannonian Basin. Glob Planet Change 171:134–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2017.10.012

Bartha IR, Szőcs E, Tőkés L (2015) Reservoir quality of the Late Miocene turbidites from the eastern Transylvanian Basin, Romania: depositional environment and porosity evolution. Földtani Közlöny 146:257–274 (in Hungarian with English abstract)

Beker K, Tunoğlu C, Ertekin İK (2008) Pliocene-Lower Pleistocene Ostracoda fauna from İnsuyu Limestone (Karapınar-Konya/Central Turkey) and its paleoenvironmental implications. Pliyosen-Pleyistosen Yaşlı İnsuyu Kireçtaşı’nın Ostrakod Faunası (Karapınar-Konya/İç Anadolu, Türkiye) ve Eski Ortamsal Yorumu. Türkiye Jeoloji Bülteni 51:1–32

Bérczi I, Phillips RL (1985) Process and depositional environments within Neogene deltaic-lacustrine sediments, Pannonian Basin, Southeast Hungary. Geophys Trans 31:55–74

Boomer I, Grafenstein U, Guichard F, Bieda S (2005) Modern and Holocene sublittoral ostracod assemblages (Crustacea) from the Caspian Sea: a unique brackish, deep-water environment. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 225:173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.10.023

Botka D, Magyar I, Csoma V, Tóth E, Šujan M, Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger Z, Chyba A, Braucher R, Sant K, Ćorić S, Baranyi V, Bakrač K, Krizmanić K, Bartha IR, Szabó M, Silye L (2019) Integrated stratigraphy of the Guşteriţa clay pit: a key section for the early Pannonian (late Miocene) of the Transylvanian Basin (Romania). Aust J Earth Sci 112:221–247. https://doi.org/10.17738/ajes.2019.0013

Brooks HL, Hodgson DM, Brunt RL, Peakall J, Hofstra M, Flint SS (2018) Deep-water channel-lobe transition zone dynamics: processes and depositional architecture, an example from the Karoo Basin, South Africa. GSA Bull 130:1723–1746. https://doi.org/10.1130/b31714.1

Bruch AA, Utescher T, Mosbrugger V, Gabrielyan I, Ivanov DA (2006) Late Miocene climate in the circum-Alpine realm—a quantitative analysis of terrestrial palaeofloras. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 238:270–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.03.028

Budai S, Sebe K, Nagy G, Magyar I, Sztanó O (2019) Interplay of sediment supply and lake-level changes on the margin of an intrabasinal basement high in the Late Miocene Lake Pannon (Mecsek Mts., Hungary). Int J Earth Sci 108:2001–2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-019-01745-3

Carvajal C, Steel R (2009) Shelf-edge architecture and bypass of sand to deep water: Influence of shelf-edge processes, sea level, and sediment supply. J Sediment Res 79:652–672. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2009.074

Carvajal C, Steel R, Petter A (2009) Sediment supply: the main driver of shelf-margin growth. Earth Sci Rev 96:221–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2009.06.008

Chivu M, Valentina V, Enache G, Isac D, Margarit E (1966) Contribuții la stratigrafia Neogenului din bazinul Silvaniei. Dări de Seamă ale Şedințelor. Com Geol 52:239–254

Ciulavu D, Dinu C, Cloetingh SAPL (2002) Late Cenozoic tectonic evolution of the Transylvanian basin and northeastern part of the Pannonian basin: constraints from seismic profiling and numerical modelling. In: Cloetingh SAPL, Horváth F, Bada G, Lankreijer AC (eds) Neotectonics and surface processes: the Pannonian Basin and Alpine/Carpathian System. EGU Stephan Mueller Special Publication Series 3, pp 105–120. 10.5194/smsps-3-105-2002

Clichici O (1973) Stratigrafia neogenului din estul Bazinul Șimleu. Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, București (in Romanian)

Cloetingh S, Maţenco L, Bada G, Dinu C, Mocanu V (2005) The evolution of the Carpathians–Pannonian system: interaction between neotectonics, deep structure, polyphase orogeny and sedimentary basins in a source to sink natural laboratory. Tectonophysics 410:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2005.08.014

Codrea V, Margin C (2009) The environments of the uppermost Miocene vertebrates from Derşida (Northwestern Rumania, Sălaj County). Studii Şi Comunicări Ştiinţele Naturii 25:385–390

Codrea VA, Fărcaş C, Săsăran E, Dica PE (2002) A Late Miocene mammal fauna from Derşida (Sălaj district) and its related paleoenvironment. Stud Univ Babes-Bolyai Ser Geol Spec Issue 1:119–132

Colella A (1988) Pliocene–Holocene fan deltas and braid deltas in the Crati Basin, southern Italy: a consequence of varying tectonic conditions. In: Nemec W, Steel RJ (eds) Fan deltas: sedimentology and tectonic settings. Blackie, London, pp 50–74

Collinson JD (1996) Alluvial sediments. In: Reading HG (ed) Sedimentary environments: processes, facies and stratigraphy. Blackwell Science, Oxford, pp 37–83

Csató I, Tóth S, Catuneanu O, Granjeon D (2015) A sequence stratigraphic model for the Upper Miocene–Pliocene basin fill of the Pannonian Basin, eastern Hungary. Mar Pet Geol 66:117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2015.02.010

Cziczer I, Magyar I, Pipík R, Böhme M, Ćorić S, Bakrač K, Müller P (2009) Life in the sublittoral zone of long-lived Lake Pannon: paleontological analysis of the Upper Miocene Szák Formation, Hungary. Int J Earth Sci 98:1741–1766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-008-0322-3

Danielopol DL, Gross M, Harzhauser M, Minati K, Piller WE (2011) How and why to achieve greater objectivity in taxonomy, exemplified by a fossil ostracod (Amplocypris abscissa) from the Miocene Lake Pannon. Joannea Geologie Und Paläontologie 11:273–326

Fodor L, Csontos L, Bada G, Györfi I, Benkovics L (1999) Tertiary tectonic evolution of the Pannonian Basin system and neighbouring orogens: a new synthesis of palaeostress data. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 156:295–334. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.1999.156.01.15

Gawthorpe RL, Colella A (1990) Tectonic controls on coarse-grained delta depositional system in rift basin. In: Colella A, Prior B (eds) Coarse-grained deltas. International Association of Sedimentologists Special Publication 10, pp 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444303858.ch6

Geary DH, Magyar I, Müller P (2000) Ancient Lake Pannon and its endemic molluscan fauna (Central Europe; Mio-Pliocene). In: Rossiter A, Kawanabe H (eds) Ancient lakes: biodiversity, ecology, and evolution. Advances in ecological research, vol 3. Academic Press, pp 463–482

Gobo K, Ghinassi M, Nemec W (2015) Gilbert-type deltas recording short-term base-level changes: delta-brink morphodynamics and related foreset facies. Sedimentology 62:1923–1949. https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.12212

Harzhauser M, Daxner-Höck G, Piller WE (2004) An integrated stratigraphy of the Pannonian (Late Miocene) in the Vienna Basin. Aust J Earth Sci 95–96:6–19

Hilgen FJ, Lourens LJ, van Dam JA, Beu AG, Boyes AF, Cooper RA, Krijgsman W, Ogg JG, Piller WE, Wilson DS (2012) The Neogene period. In: Gradstein FM, Ogg JG, Schmitz MD, Ogg GM (eds) The geologic time scale 2012. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 923–978. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-59425-9.00029-9

Horusitzky H (1907) Die agrogeologischen Verhältnisse des südlichen Teiles der Kleinen Karpathen. Jahresbericht Der Königlichen Ungarischen Geologischen Anstalt Für 1907:141–167

Horváth F, Pogácsás G (1988) Contribution of seismic reflection data to chronostratigraphy of the Pannonian basin. In: Royden LH, Horváth F (eds) The Pannonian basin. A study in basin evolution. AAPG Memoir 45, pp 97–105

Horváth F, Royden LH (1981) Mechanism for formation of the intra-Carpathian basins: a review. Earth Evol Sci 1:307–316

Horváth F, Bada G, Szafián P, Tari G, Ádám A, Cloetingh S (2006) Formation and deformation of the Pannonian Basin: constraints from observational data. In: Gee DG, Stephenson RA (eds) European Lithosphere Dynamics. Geological Society, London, Memoirs 32, pp 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1144/gsl.mem.2006.032.01.11

Horváth F, Musitz B, Balázs A, Végh A, Uhrin A, Nádor A, Koroknai B, Pap N, Tóth T, Wórum G (2015) Evolution of the Pannonian basin and its geothermal resources. Geothermics 53:328–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geothermics.2014.07.009

Johnson SD, Flint S, Hinds D, Wickens HD (2001) Anatomy, geometry and sequence stratigraphy of basin floor to slope turbidite systems, Tanqua Karoo, South Africa. Sedimentology 48:987–1024. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3091.2001.00405.x

Joniak P (2016) Upper Miocene rodents from Pezinok in the Danube Basin, Slovakia. Acta Geologica Slovaca 8:1–14

Jordan DW, Pryor WA (1992) Hierarchical levels of heterogeneity in a Mississippi River meander belt and application to reservoir systems. AAPG Bull 76:1601–1624. https://doi.org/10.1306/BDFF8A6A-1718-11D7-8645000102C1865D

Jorissen EL, de Leeuw A, van Baak CG, Mandic O, Stoica M, Abels HA, Krijgsman W (2018) Sedimentary architecture and depositional controls of a Pliocene river-dominated delta in the semi-isolated Dacian Basin, Black Sea. Sed Geol 368:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2018.03.001

Juhász G (1994) Comparison of the sedimentary sequences in Late Neogene subbasins in the Pannonian Basin, Hungary. Földtani Közlöny 124:341–365

Kázmér M (1990) Birth, life and death of the Pannonian Lake. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 79:171–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(90)90111-j

Kneller B, Branney MJ (1995) Sustained high-density turbidity currents and the deposition of thick massive sands. Sedimentology 42:607–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.1995.tb00395.x

Konidaris GE, Roussiakis SJ (2018) The first record of Anancus (Mammalia, Proboscidea) in the late Miocene of Greece and reappraisal of the primitive anancines from Europe. J Vertebr Paleontol 38(6):e1534118. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2018.1534118

Kováč M, Baráth I, Kováčová-Slamková M, Pipík R, Hlavatý I, Hudáčková N (1998) Late Miocene paleoenvironments and sequence stratigraphy: northern Vienna Basin. Geol Carpath 49:445–458

Kovácic M, Zupanic J, Babic L, Vrsaljko D, Miknic M, Bakrac K, Hecimovic I, Avanic R, Brkic M (2004) Lacustrine basin to delta evolution in the Zagorje Basin, a Pannonian sub-basin (Late Miocene: Pontian, NW Croatia). Facies 50:19–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10347-003-0001-6

Kováč M, Synak R, Fordinál K, Joniak P, Cs T, Vojtko R, Nagy A, Baráth I, Maglay J, Minár J (2011) Late Miocene and Pliocene history of the Danube Basin: inferred from development of depositional systems and timing of sedimentary facies changes. Geol Carpath 62:519–534. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10096-011-0037-4

Kováč M, Rybár S, Halásová E, Hudáčková N, Šarinová K, Šujan M, Baranyi V, Kováčová M, Ruman A, Klučiar T, Zlinská A (2018) Changes in Cenozoic depositional environment and sediment provenance in the Danube Basin. Basin Res 30:97–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/bre.12244

Krézsek CS, Bally AW (2006) The Transylvanian Basin (Romania) and its relation to the Carpathian fold and thrust belt: Insights in gravitational salt tectonics. Mar Pet Geol 23:405–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2006.03.003

Krézsek C, Filipescu S, Silye L, Maţenco L, Doust H (2010) Miocene facies associations and sedimentary evolution of the Southern Transylvanian Basin (Romania): implications for hydrocarbon exploration. Mar Pet Geol 27:191–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.07.009

Krstić N (1985) Ostracoden im Pannonien der Umgebung von Belgrad. In: Papp A, Jámbor Á, Steininger FF (eds) Chronostratigraphie und Neostratotypen: Miozän der Zentralen Paratethys VII, M6, Pannonien. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, pp 103–143

Lemberkovics V, Bárány Á, Gajdos I, Vincze M (2005) A szekvencia-sztratigráfiai események és a tektonika kapcsolata a Derecskei-árok pannóniai rétegsorában. Seismic stratigraphic events and tectonics in the Pannonian deposits of the Derecske trough. Földtani Kutatás 42:16–23 (in Hungarian)

Lőrenthey I (1893) Beiträge zur Kenntniss der unterpontischen Bildungen des Szilágyer Comitates und Siebenbürgens. Sitzungsberichte der medicinisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Section des siebenbürgischen Museumvereins. I. Naturwissenschaftliche Abtheilung 15:289–322

Lowe DR (1982) Sediment gravity flows: II. Depositional models with special reference to the deposits of high-density turbidity currents. J Sediment Res 52:279–297. https://doi.org/10.1306/212F7F31-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865D

Lubenescu V, Crahmaliuc G, Radu M (1967) Observations on the stratigraphy and fauna of the Pannonian deposits in the Silvania Basin. Dări De Seamă Ale Ședințelor 52:63–72 (in Romanian with English and French abstracts)

Lyubas AA, Obada TF, Gofarov MY, Kriauciunas VV, Vikhrev IV, Nicoara IN, Bolotov IN (2019) A taxonomic revision of fossil freshwater pearl mussels (Bivalvia: Unionoida: Margaritiferidae) from Pliocene and Pleistocene deposits of Southeastern Europe. Ecologica Montenegrina 21:1–16. https://doi.org/10.37828/em.2019.21.1

Magyar I, Geary DH (2012) Biostratigraphy in a late Neogene Caspian-type lacustrine basin: Lake Pannon, Hungary. In: Baganz OW, Bartov Y, Bohacs K, Nummedal D (eds) Lacustrine sandstone reservoirs and hydrocarbon systems. AAPG Memoir 95, pp 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1306/13291392M953142

Magyar I, Geary DH, Müller P (1999a) Paleogeographic evolution of the Late Miocene Lake Pannon in Central Europe. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 147:151–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(98)00155-2

Magyar I, Müller P, Geary DH, Sanders HC, Tari GC (1999b) Diachronous deposits of Lake Pannon in the Kisalföld basin reflect basin and mollusc evolution. Abhandlungen Der Geologischen Bundesanstalt 56:669–678

Magyar I, Lantos M, Ujszászi K, Kordos L (2007) Magnetostratigraphic, seismic and biostratigraphic correlations of the Upper Miocene sediments in the northwestern Pannonian Basin System. Geol Carpath 58:277–290

Magyar I, Radivojević D, Sztanó O, Synak R, Ujszászi K, Pócsik M (2013) Progradation of the paleo-Danube shelf margin across the Pannonian Basin during the Late Miocene and Early Pliocene. Glob Planet Change 103:168–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.06.007

Magyar I, Cziczer I, Sztanó O, Dávid Á, Johnson M (2016) Palaeobiology, palaeoecology and stratigraphic significance of the Late Miocene cockle Lymnocardium soproniense from Lake Pannon. Geol Carpath 67:561–571. https://doi.org/10.1515/geoca-2016-0035

Magyar I, Sztanó O, Csillag G, Kercsmár Z, Katona L, Lantos Z, Bartha IR, Fodor L (2017) Pannonian molluscs and their localities in the Gerecse Hills, Transdanubian Range: stratigraphy, paleoenvironment, geological evolution. Földtani Közlöny 147:149–176. https://doi.org/10.23928/foldt.kozl.2017.147.2.149 (in Hungarian with English abstract)

Magyar I, Sztanó O, Sebe K, Katona L, Csoma V, Görög Á, Tóth E, Szuromi-Korecz A, Šujan M, Braucher R, Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger Z, Koroknai B, Wórum G, Sant K, Kelder N, Krijgsman W (2019) Towards a high-resolution chronostratigraphy and geochronology for the Pannonian Stage: Significance of the Paks cores (Central Pannonian Basin). Földtani Közlöny 149:351–370. https://doi.org/10.23928/foldt.kozl.2019.149.4.351

Marinescu F (1985) Der Östliche Teil des Pannonischen Beckens (Rumänischer Sektor): Das Pannonien s. str. (Malvensien). In: Papp A, Jámbor Á, Steininger FF (eds) Chronostratigraphie und Neostratotypen. Miozän der Zentralen Paratethys VII, M6, Pannonien. Akademiai Kiadó, Budapest, pp 144–154

Martini I, Sandrelli F (2015) Facies analysis of a Pliocene river-dominated deltaic succession (Siena Basin, Italy): implications for the formation and infilling of terminal distributary channels. Sedimentology 62:234–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/sed.12147

Marton G (1985) A derecskei mélyzóna szeizmosztratigráfiai vizsgálata. Seismic stratigraphic study of the Derecske depression. Magyar Geofizika 26:161–181 (in Hungarian with English abstract)

Matenco L, Munteanu I, ter Borgh M, Stanica A, Tilita M, Lericolais G, Dinu C, Oaie G (2016) The interplay between tectonics, sediment dynamics and gateways evolution in the Danube system from the Pannonian Basin to the western Black Sea. Sci Total Environ 543:807–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.081

Mattick RE, Phillips RL, Rumpler J (1988) Seismic stratigraphy and depositional framework of sedimentary rocks in the Pannonian basin in southeastern Hungary. In: Royden LH, Horváth F (eds) The Pannonian basin. A study in basin evolution. AAPG Memoir 45, pp 117–145

Matyasovszky J (1879) Bericht über geologische Detailaufnahmen im Comitate Szilágy im Jahre 1878. Földtani Közlöny 9:333–341

Maxim IAL, Ghiurcă V (1960) Formes nouvelles de mollusques du Pliocéne supérieur de Derşida (Sălaj). Comunicările Academiei Republicii Populare Române 10:595–605 (in Romanian with French and Russian abstracts)

Maxim IAL, Ghiurcă V (1963) Varietăţi de forme la Unio wetzleri flabellatiformis Mik. din pliocenul de la Derşida-Sălaj. Studii Şi Cercetări De Geologie 1:13–33 (in Romanian)

Maxim IAL, Ghiurcă V (1964) Variations de formes chez Unio wetzleri flabellatiformis Mik., dans le Pliocene de Derşida-Sălaj. Rev Roum Géol 8:11–20 (in Romanian)

Morkhoven FPCM (1963) Post-Palaeozoic Ostracoda: their morphology, taxonomy and economic use, vol 1. Elsevier

Müller P, Szónoky M (1990) Faciostratotype the Tihany-Fehérpart (Hungary) (“Balatonica Beds”, by Lőrenthey, 1905). In: Stevanović P, Nevesskaja LA, Marinescu Fl, Sokać A, Jámbor Á (eds) Chronostratigraphie und Neostratotypen, Neogen der Westlichen (“Zentrale”) Paratethys, VIII, Pl1 Pontien. JAZU and SANU, Zagreb-Beograd, pp 427–435

Nemec W (1990) Aspects of sediment movement on steep delta slopes. In: Colella A, Prior B (eds) Coarse-grained deltas. Special Publications of the International Association of Sedimentologists, vol 10, pp 29–73

Neubauer TA, Georgopoulou E, Harzhauser M, Mandic O, Kroh A (2016) Predictors of shell size in long-lived lake gastropods. J Biogeogr 43:2062–2074. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12777

Nicorici E (1972) Stratigrafia neogenului din sudul Bazinului Șimleu. Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, București (in Romanian)

Nicorici E, Karácsonyi C (1983) La faune pannonienne de Nadişul Hododului (Bassin Simleu) et sa signification stratigraphique. Memoriile Secţiilor Ştiinţifice 4:227–233 (in Romanian with French abstract)

Olariu C, Bhattacharya JP (2006) Terminal distributary channels and delta front architecture of river-dominated delta systems. J Sediment Res 76:212–233. https://doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2006.026

Panait-Patica A, Serban D, Ilie N, Pavel L, Barsan N (2006) Suplacu de Barcau Field—a case history of a successful in-situ combustion exploitation. SPE-100346-MS. https://doi.org/10.2118/100346-MS

Papp S (1915) Das neue Vorkommen der pannonischen Petrefakten Congeria spathulata Partsch und Limnocardium Penslii Fuchs in Ungarn und die auf dieselben bezügliche Literatur. Földtani Közlöny 45:311–315

Papp A (1950) Übergangsformen von Congeria zu Dreissena aus dem Pannon des Wiener Beckens. Annalen Des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien 57:148–156

Papp A (1985) Gastropoda (Neritidae, Viviparidae, Valvatidae, Hydrobiidae, Stenothyridae, Truncatellidae, Bulimidae, Micromelaniidae, Thiaridae) und Bivalvia (Dreissenidae, Limnocardiidae, Unionidae) des Pannonien. In: Papp A, Jámbor Á, Steininger FF (eds) Chronostratigraphie und Neostratotypen. Miozän der Zentralen Paratethys VII, M6, Pannonien. Akademiai Kiadó, Budapest, pp 276–339

Paucă M (1954) Două specii de fosile rare din pliocenul Bazinului Sălaj. Comunicările Academiei Republicii Populare Romîne 4:397–400 (in Romanian)

Pavelić D, Kovačić M (2018) Sedimentology and stratigraphy of the Neogene rift-type North Croatian Basin (Pannonian Basin System, Croatia): a review. Mar Pet Geol 91:455–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.01.026

Pavlović PS (1928) Les mollusques du pontien inférieur des environs de Beograd. Annales Géologiques De La Péninsule Balkanique 9:1–74

Phillips S, Bustin RM (1996) Sedimentology of the Changuinola peat deposit: organic and clastic sedimentary response to punctuated coastal subsidence. GSA Bull 108:794–814. https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1996)108%3c0794:SOTCPD%3e2.3.CO;2

Pigott JD, Radivojević D (2010) Seismic stratigraphy based chronostratigraphy (SSBC) of the Serbian Banat region of the Pannonian Basin. Central Eur J Geosci 2:481–500. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10085-010-0027-2

Plink-Björklund P, Steel RJ (2004) Initiation of turbidity currents: outcrop evidence for Eocene hyperpycnal flow turbidites. Sed Geol 165:29–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2003.10.013

Pogácsás G (1984) A Pannon medence neogén mélydepresszióinak szeizmikus sztratigráfiai alapvonásai. Seismic stratigraphic features of the deep Neogene depressions of the Pannonian Basin. Magyar Geofizika 25:151–166 (in Hungarian with English abstract)

Pogácsás G, Révész I (1987) Seismic stratigraphic and sedimentological analysis of Neogene delta features in the Pannonian basin. Ann Hung Geol Inst 70:267–273

Pogácsás G, Lakatos L, Révész I, Ujszászi K, Vakarcs G, Várkonyi L, Várnai P (1988) Seismic facies, electro facies and Neogene sequence chronology of the Pannonian Basin. Acta Geol Hung 31:175–207

Postma G (1990) Depositional architecture and facies of river and fan deltas: a synthesis. In: Colella A, Prior B (eds) Coarse-grained deltas. International Association of Sedimentologists, Special Publication 10, pp 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444303858.ch2

Postma G, Hoyal DC, Abreu V, Cartigny MJ, Demko T, Fedele JJ, Kleverlaan K, Pederson KH (2016) Morphodynamics of supercritical turbidity currents in the channel-lobe transition zone. In: Lamarche G et al (eds) Submarine mass movements and their consequences. Springer, pp 469–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20979-1_47

Răbăgia AM (2009) Sequential stratigraphic studies in the northern part of the Pannonian Basin for deriving the tectono-stratigraphic evolution. Dissertation, University of Bucharest

Reading HG, Collinson JD (1996) Clastic coasts. In: Reading HG (ed) Sedimentary environments: processes, facies and stratigraphy. Blackwell Science, Oxford, pp 154–231

Révész I (1980) Hydrocarbon deposit Algyő-2: geological structure, sedimentological heterogeneity and palaeogeographic features. Földtani Közlöny 110:512–539 (in Hungarian with English abstract)

Rögl F (1999) Mediterranean and Paratethys. Facts and hypotheses of an Oligocene to Miocene paleogeography (short overview). Geol Carpath 50:339–349

Ruszkiczay-Rüdiger Z, Balázs A, Csillag G, Drijkoningen G, Fodor L (2020) Uplift of the transdanubian range, Pannonian Basin: how fast and why? Glob Planet Change 192:103263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2020.103263

Sacchi M, Cserny T, Dövényi P, Horváth F, Magyari O, Mcgee TM, Mirable L, Tonielli R (1998) Seismic stratigraphy of the Late Miocene sequence beneath Lake Balaton, Pannonian basin, Hungary. Acta Geol Hung 41:63–88

Schomacker ER, Kjemperud AV, Nystuen JP, Jahren JS (2010) Recognition and significance of sharp-based mouth-bar deposits in the Eocene Green River Formation, Uinta Basin, Utah. Sedimentology 57:1069–1087. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.2009.01136.x

Sebe K, Kovačić M, Magyar I, Krizmanić K, Špelić M, Bigunac D, Sütő-Szentai M, Kovács Á, Szuromi-Korecz A, Bakrač K, Hajek-Tadesse V, Troškot-Čorbić T, Sztanó O (2020) Correlation of upper Miocene–Pliocene Lake Pannon deposits across the Drava Basin, Croatia and Hungary. Geologia Croatica 73:177–195. https://doi.org/10.4154/gc.2020.12

Stoica M, Lazăr I, Krijgsman W, Vasiliev I, Jipa D, Floroiu A (2013) Paleoenvironmental evolution of the East Carpathian foredeep during the late Miocene–early Pliocene (Dacian Basin; Romania). Glob Planet Change 103:135–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.04.004

Strausz L (1941) Pannóniai fauna Dernáról és Tatarosról. Pannonian fauna from Derna and Tataros. Beszámoló a m. kir. Földtani Intézet vitaüléseinek munkálatairól. A m. kir. Földtani Intézet 1941. Évi Jelentésének Függeléke 3:192–198 (in Hungarian)

Šujan M, Braucher R, Kováč M, Bourlés DL, Rybár S, Guillou V, Hudácková N (2016) Application of the authigenic 10Be/9Be dating method to Late Miocene–Pliocene sequences in the northern Danube Basin (Pannonian Basin System): confirmation of heterochronous evolution of sedimentary environments. Glob Planet Change 137:35–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2015.12.013

Szakács A, Pécskay Z, Silye L, Balogh K, Vlad D, Fülöp A (2012) On the age of the Dej Tuff, Transylvanian Basin (Romania). Geol Carpath 63:139–148. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10096-012-0011-9

Sztanó O, Magyari Á, Tóth P (2010) Gilbert-type delta in the Pannonian Kálla Gravel near Tapolca, Hungary. Földtani Közlöny 140:167–182 (in Hungarian with English abstract)

Sztanó O, Magyar I, Szónoky M, Lantos M, Müller P, Lenkey L, Katona L, Csillag G (2013a) Tihany Formation in the surroundings of Lake Balaton: type locality, depositional setting and stratigraphy. Földtani Közlöny 143:73–98 (in Hungarian with English abstract)

Sztanó O, Szafián P, Magyar I, Horányi A, Bada G, Hughes DW, Hoyer DL, Wallis RJ (2013b) Aggradation and progradation controlled clinothems and deep-water sand delivery model in the Neogene Lake Pannon, Makó Trough, Pannonian Basin, SE Hungary. Glob Planet Change 103:149–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.05.026

Sztanó O, Kováč M, Magyar I, Šujan M, Fodor L, Uhrin A, Rybár S, Csillag G, Tőkés L (2016) Late Miocene sedimentary record of the Danube/Kisalföld Basin: interregional correlation of depositional systems, stratigraphy and structural evolution. Geol Carpath 67:525–542. https://doi.org/10.1515/geoca-2016-0033

Talling PJ, Masson DG, Sumner EJ, Malgesini G (2012) Subaqueous sediment density flows: depositional processes and deposit types. Sedimentology 59:1937–2003. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3091.2012.01353.x

Teleki PG, Mattick RE, Kókay J (eds) (1994) Basin analysis in petroleum exploration. A case study from the Békés basin, Hungary. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

ter Borgh M, Vasiliev I, Stoica M, Knežević S, Maţenco L, Krijgsman W, Rundić L, Cloetingh S (2013) The isolation of the Pannonian basin (Central Paratethys): new constraints from magnetostratigraphy and biostratigraphy. Glob Planet Change 103:99–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.10.001

Tiliţă M, Matenco L, Dinu C, Ionescu L, Cloetingh S (2013) Understanding the kinematic evolution and genesis of a back-arc continental “sag” basin: the Neogene evolution of the Transylvanian Basin. Tectonophysics 602:237–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2012.12.029

Tőkés L, Patacci M (2018) Quantifying tabularity of turbidite beds and its relationship to the inferred degree of basin confinement. Mar Pet Geol 97:659–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2018.06.012

Tőkés L, Bartha IR, Silye L, Cs K, Sztanó O (2021) Multiple-scale incision-infill cycles in deep-water channels from the lacustrine Transylvanian Basin, Romania: auto- or allogenic controls? Glob Planet Change. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2021.103511

Trkulja N, Kirin Ž (1984) Phenomenon of dip reflections on the conventional seismic lines of NE Vojvodina. Nafta 35:11–19 (in Croatian with English and Russian abstracts)

Tulucan A (2007) Complex geological study of the Romanian sector of the Pannonian Depression with special regard to hydrocarbon accumulation. Dissertation, University of Bucharest