Abstract

Purpose

Older breast cancer survivors (BCS) may be at greater risk for cognitive dysfunction and other comorbidities; both of which may be associated with physical and emotional well-being. This study will seek to understand these relationships by examining the association between objective and subjective cognitive dysfunction and physical functioning and quality of life (QoL) and moderated by comorbidities in older BCS.

Methods

A secondary data analysis was conducted on data from 335 BCS (stages I–IIIA) who were ≥ 60 years of age, received chemotherapy, and were 3–8 years post-diagnosis. BCS completed a one-time questionnaire and neuropsychological tests of learning, delayed recall, attention, working memory, and verbal fluency. Descriptive statistics and separate linear regression analyses testing the relationship of each cognitive assessment on physical functioning and QoL controlling for comorbidities were conducted.

Results

BCS were on average 69.79 (SD = 3.34) years old and 5.95 (SD = 1.48) years post-diagnosis. Most were stage II (67.7%) at diagnosis, White (93.4%), had at least some college education (51.6%), and reported on average 3 (SD = 1.81) comorbidities. All 6 physical functioning models were significant (p < .001), with more comorbidities and worse subjective attention identified as significantly related to decreased physical functioning. One model found worse subjective attention was related to poorer QoL (p < .001). Objective cognitive function measures were not significantly related to physical functioning or QoL.

Conclusions

A greater number of comorbidities and poorer subjective attention were related to poorer outcomes and should be integrated into research seeking to determine predictors of physical functioning and QoL in breast cancer survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Comorbidities are common among older adults; the majority (80%) have at least one comorbid condition, with the most common comorbidities being cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and arthritis [1]. In addition, individuals who have had cancer tend to report more comorbidities than those with no history of cancer [2]. Cognitive dysfunction, a common cancer-related symptom experienced by breast cancer survivors (BCS), has been associated with comorbidities in the non-oncology aging literature [3]. Findings about the relationship between comorbidities and cognitive dysfunction in older BCS specifically have begun to be addressed in the literature as well, although findings have been mixed [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Given the magnitude of comorbidities and cognitive dysfunction in older BCS, research on these associations is critical.

Additionally, both comorbidities and cognitive dysfunction have been related to decreased levels of physical functioning [11] and decreased quality of life (QoL) in older adults [12, 13]. Physical functioning is critical to independent living and QoL for older adults [14]. Decreased physical functioning can lead to the need for hospitalization, long-term care, and premature death [14]. Physical functioning and lower symptom burden is related to QoL in older adults and functional ability is identified as a critical factor in overall life satisfaction [15]. In general, poor cognitive and physical functioning as well as disruptions in QoL have far reaching implications and may impact the daily lives of older adults [13,14,15,16]. Investigation of these relationships in older BCS is reflected in the literature, although most research has been focused on older BCS in treatment and up to 2 years post-treatment, with little attention to these relationships in longer-term BCS [17].

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine comorbidities, objective cognitive function, and subjective cognitive function and their relationship with physical functioning and QoL in older BCS 3–8 years post-diagnosis, controlling for age and education. This study is important and may be useful for older BCS, and their families and caregivers, as well as healthcare providers, including primary care providers or geriatricians who will be caring for older BCS. Understanding the relationships between comorbidities, cognitive dysfunction, physical functioning, and QoL is essential to developing evidence-based survivorship care models that address the needs of older BCS throughout survivorship.

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of cross-sectional data leveraged from a large American Cancer Society-funded BCS study whose purpose was to examine QoL in younger versus older BCS (RSGPB-04–089-01, PI: Champion) [18].

Population and data collection

The analyses for this paper focused on older BCS who were 60 years of age and older, 3–8 years post-diagnosis for stage I–IIIA breast cancer without recurrence and treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Procedures for the original study have been published previously [18]. Briefly, eligible BCS were recruited from 97 Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) sites and the primary research site, a Midwestern University in the USA. Willing and eligible BCS completed mailed questionnaires documenting information including demographics, comorbidities, subjective cognitive functioning, physical functioning, and QoL. In addition, participants completed a brief telephone-based neuropsychological assessment with previously validated psychometrics [19]. Participants were paid a small incentive ($50 total) for completing the one-time questionnaires and the telephone-based neuropsychological assessment. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the primary research site and all participating ECOG sites.

Measures

Demographic

Standard demographic data (i.e., age, education, race, ethnicity, marital status) were collected via an investigator-initiated self-report questionnaire.

Comorbidities

Comorbidities were collected via self-report survey where BCS responded yes or no to a list of 18 potential comorbid conditions including arthritis, heart disease or heart problem, high blood pressure or hypertension, stroke, serious breathing disease or problem, kidney disease or problem, high cholesterol, diabetes, leukemia or cancer (but did not include breast cancer), anxiety/panic disorders, depression, eating disorders, hip fracture, surgical replacement of joint, problem with urinary control, eye problems (other than corrective lenses), hearing problems, and other problem—please specify. For the current analyses, we used the total number of comorbidities reported.

Objective cognitive function

Objective cognitive function including learning, delayed recall, attention, executive function-working memory, and verbal fluency was assessed using valid and reliable neuropsychological assessments that have been used in BCS. The Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) was used to assess learning and delayed recall by completing a 15-word learning task, where the tester lists 15 words, and the participant must attempt to recall and recite [20,21,22]. For both learning and delayed recall, higher scores indicate better functioning [20,21,22]. The Digit Span Forward and Backward were used to assess attention and executive function-working memory, respectively. For the Digit Span test, the tester lists numbers in a string and the participant must recite them in order for the Forward test and must recite the numbers in reverse order for the Backward test [23, 24]. For both the Digit Span-Forward and Backward, higher scores indicate better functioning [23, 24]. The Benton Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWA) was used to assess verbal fluency by giving the participant a letter and 1 min to produce as many words as possible that begin with that letter (excluding proper nouns) [25,26,27]. Potential and actual score ranges for this test vary however higher scores indicate better functioning [25,26,27].

Subjective cognitive function

The Attentional Function Index (AFI) is a 13-item scale used to assess the participants’ perceived effectiveness in activities requiring attention, working memory, and executive function, such as planning daily activities, finishing things you have started, and keeping your train of thought [28]. Potential scores can range from 0 to 130; higher scores indicate better subjective attention functioning [28]. In this study, the AFI Cronbach alpha was 0.80.

Physical functioning

The Physical Functioning Scale (PF-10) is a subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). The PF-10 is 10 items and measures the participants’ perceived limitations of physical functioning; higher scores indicate less limitation or disability [29]. The PF-10 is an established measure of physical functioning that has shown reliability and validity in various populations including cancer patients [29]. In this study, the Cronbach alpha was 0.89.

Quality of life

The Index of Well-Being-Survivor (IWB) instrument measures overall QoL including life satisfaction and subjective well‐being [30]. This is a 9-item measure developed to assess specific concerns of long-term cancer survivors; higher scores indicate higher/better QoL. The IWB scale has established reliability and validity and has been widely used in cancer patients including BCS [18, 31]. In this study, the Cronbach alpha was 0.92.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe the sample. Separate linear regression models were used to examine the relationships between the independent variables of comorbidities and both subjective cognitive function (attention) and objective cognitive assessment (learning, delayed recall, attention, executive function-working memory, and verbal fluency) and dependent variables of physical functioning (PF-10) and QoL (IWB), controlling for age and education in older BCS. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all analyses and SPSS statistical software, version 26, was used for data analysis.

An a priori power analysis was calculated based on the statistical approach described, using power estimates for a performing a linear regression model with continuous variables. Effect size estimates for estimating a model with an R2 value of 2% (small), 5% (small-medium), 13% (medium), and 26% (large) were derived from Cohen [32]. Analysis shows the sample of 335 participants has sufficient power to detect both medium and large effect sizes for any regression model ranging from one to ten independent variables, the smallest effect size (between small and medium) where all possible models will have at least 80% power. This corresponds to an effect size of f2 = 0.05 or R2 value of 5%.

Results

Older BCS (n = 335) who participated in this study were 3–8 years post-diagnosis (M 5.95, SD 1.48), 63.85 years of age on average (SD 2.97), and with a mean of 13.73 (SD 2.53) years of education, indicating most BCS had at least some education beyond high school (see Table 1). On average, long-term older BCS reported having 3 (SD 1.81) comorbid conditions, with total number of comorbid conditions ranging from 0 to 12 throughout this sample. The most common comorbidities reported were hypertension (n = 192; 57.3%), arthritis (n = 186; 55.5%), and high cholesterol (n = 151; 45.1%). Table 1 depicts a more thorough breakdown of comorbidities reported by long-term older BCS in this study.

The regression analyses examining number of comorbidities and objective cognitive function or subjective cognitive function scores and their relationship with physical functioning and QoL, controlling for confounders of age and education in older BCS, are displayed in Table 2. Results for each regression analyses (labeled by the independent cognitive domain variable) are described below.

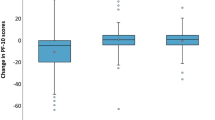

Physical functioning

Physical functioning scores can range from 0 to 100; in this sample, scores were on average 70.71 (SD 22.94); higher scores indicate better physical functioning or less limitation. Learning: The model including age, education, comorbidities, and learning was significant [F(4,321) = 27.15, adjusted r2 = 0.24; p < 0.001]. The model explained 24% of the variance of physical functioning, with education (β = 0.12, p˂0.05) and the number of comorbidities (β = − 0.48, p˂0.001) related to physical functioning. These results indicated that more education was positively related to physical function and more comorbidities was negatively related to physical function. Delayed recall: Age, education, number of comorbidities, and delayed recall predicted physical functioning [F(4,321) = 26.95, adjusted r2 = 0.24; p < 0.001], explaining 24% of the variance of physical functioning. Higher levels of education (β = 0.12, p˂0.05) and a lower number of comorbidities (β = − 0.48, p˂0.001) were related to better physical functioning. Attention: The model with age, education, number of comorbidities, and attention was significant [F(4,321) = 26.76, adjusted r2 = 0.24; p < 0.001], with 24% of the variance in physical functioning explained. Higher levels of education (β = 0.13, p˂0.05) and lower number of comorbidities (β = − 0.48, p˂0.001) indicated better physical functioning. Executive function-working memory: The model including age, education, number of comorbidities, and executive function-working memory was significant [F(4,321) = 26.76, adjusted r2 = 0.24; p < 0.001], with 24% of the variance of physical functioning explained. Higher levels of education (β = 0.13, p˂0.05) and lower number of comorbidities (β = − 0.48, p˂0.001) related to better physical functioning. Verbal fluency: Age, education, number of comorbidities, and verbal fluency predicted physical functioning [F(4,321) = 26.76, adjusted r2 = 0.24; p < 0.001], with 24% of the variance explained. Higher levels of education (β = 0.13, p˂0.05) and lower number of comorbidities (β = − 0.48, p˂0.001) were related to better physical functioning. Subjective attention: The model including age, education, number of comorbidities, and subjective attention was significant [F(4,312) = 33.81, adjusted r2 = 0.29; p < 0.001], with 29% of the variance of physical functioning explained. As with previous results, higher level of education (β = 0.11, p˂0.05), lower number of comorbidities (β = − 0.42, p˂0.001), and better subjective attention (β = 0.23, p˂0.001) related to better physical functioning.

Quality of life

QoL scores ranged from 8.85 to 14.7, with older BCS in this sample reporting scores of 10.03 (SD 2.31) on average with higher scores indicating better QoL. The regression analysis models for age, education, number of comorbidities and objective cognitive measures (learning, delayed recall, attention, executive function-working memory, and verbal fluency), and QoL were not significant. However, the model for subjective attention was significant. Subjective attention: Age, education, number of comorbidities, and subjective attention (AFI) predicted QoL [F(4,310) = 12.59, R2 = 0.14, adjusted r2 = 0.13; p < 0.001], with 13% of the variance in QoL explained. Better subjective attention (β = 0.39, p˂0.001) was significantly related to better QoL.

Discussion

Many older BCS experience multiple comorbidities as well as cognitive dysfunction following cancer diagnosis and treatment. Both comorbidities and cognitive dysfunction can have negative consequences in older BCS, including decreased physical functioning and lower QoL. This study illustrates the impact of comorbidities and cognitive dysfunction on physical functioning and QoL in older BCS.

Interestingly, the number of comorbidities reported was not related to QoL in any of the regression models, which contrasts the aging and cancer literature where comorbidities have been linked to QoL [12, 13]. However, comorbidities were significantly related to physical functioning in this sample of older BCS. The most common comorbidities for the older BCS in this study were similar to that of the general older adult population and included hypertension and arthritis. Approximately 94% (n = 314) of the older BCS in this study had at least one comorbid condition, as compared to 80% reported on average in the general older adult population [1]. These findings support previous literature which reports cancer survivors have more comorbidities than those without a history of cancer diagnosis and treatment [2]. Both increased comorbidities and decreased physical functioning have serious consequences in older adults [14]. These findings highlight the importance of managing comorbid conditions by healthcare providers treating older BCS. In addition, future research not only needs to examine the total number of comorbidities but should tease out the types of comorbidities that result in the greatest impairments and focus efforts on these conditions for promoting health in illness across the cancer trajectory in older BCS.

An interesting finding was that for our analyses, number of comorbidities and QoL were not related. This is in direct contrast to much of the breast cancer survivorship literature [33, 34]. However, previous literature has focused on younger or all aged BCS rather than older BCS. Researchers have shown that younger BCS often report increased symptoms and poorer quality of life than older BCS [18]. Older survivors may be more resilient than younger BCS creating less disturbance in QoL [18]. Although older BCS incur more comorbidities over time, they may be able to adapt and accept these changes as part of normal aging process more readily. However, more research is needed to fully understand the role of coping and resilience over time and its influence on QoL in longer-term survivorship for older BCS.

Subjective cognitive dysfunction, measured by the AFI, was significantly related to physical functioning. In studies among older adults, subjective cognitive dysfunction has been shown to be correlated with reports of impairment in physical functioning [35, 36]. In an older BCS study regarding trajectories of subjective cognitive decline, Mandelblatt and colleagues (2016) found that accelerated cognitive decline was associated with a decline in physical functioning in older BCS [6]. However, unlike subjective cognitive function, objective measures of cognitive function were not specifically related to physical functioning in any of the models. Similar findings have been noted in previous studies in older BCS that have examined this relationship [8,9,10]. Lange et al. (2014) found that in 123 older BCS with a mean age of 70 years, objective cognitive dysfunction was not related to performance status, which they hypothesized was likely due to a large proportion of BCS being in very good general health [8]. More research is needed to fully understand the link between cognitive dysfunction and physical functioning in older BCS.

Subjective cognitive dysfunction (subjective attention) was also significantly related to QoL. Similar findings have been noted in all ages of BCS [31] including those who are older [8, 37]. However, objective measures of cognitive function were not related to QoL in any of the models. Objective measures of cognitive dysfunction do not always correlate with subjective reports of QoL; Biglia and colleagues (2012) found that objective cognitive dysfunction was not related to QoL in 40 all age BCS [38]. In contrast, Lange et al. (2016) found that objective cognitive decline was associated with the QoL subscale of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy, Cognitive Scale (FACT-Cog) in 119 older BCS [9]. This relationship may have been the result of overlap in examining QoL concerns specific to cognitive dysfunction with this instrument [9]. Thus, findings may vary depending on the type of objective assessment and QoL measure used. Overall, more research is needed to generate data on the relationship between cognitive dysfunction and QoL. Additionally, prospective studies are needed to fully understand the impact cognitive dysfunction has on QoL in older BCS and to begin to develop interventions to address QoL in the ever-increasing population of older BCS.

We also controlled for confounding factors that may affect our outcomes including age and education. Age was not significant among any of the models. Previous studies have shown that older age is correlated with physical function decline and increased physical limitations [39, 40]. In contrast, although older adults are more likely to have functional decline and poorer health outcomes, which can impact QoL, aging itself does not negatively influence QoL [41]. Age may have not been significant in our study because we had a predominately homogeneous age group, with BCS being 60–70 years of age. If a broader age range of older BCS had been included, there would have been more variability and a greater opportunity to examine the relationship between age, physical functioning, and QoL. Level of education was significant in the models related to physical functioning, although modestly. This could be due to education acting as a proxy or indicator of income or socioeconomic status [42]. Higher level of education, income, and/or socioeconomic status has been linked to better health outcomes, including physical functioning in the larger aging literature [43]. Future research should include a larger age range of older BCS, and potentially a closer look at the impact of education, income, and/or socioeconomic status of older BCS in relationship to physical functioning and QoL outcomes is warranted.

Limitations

Although this study provides new information regarding comorbidity, cognitive functioning, physical functioning, and QoL in older BCS, there are limitations that should be addressed in future research. Data are cross-sectional in nature, providing a snapshot of the variables at one point in time and thus limiting the ability to determine casual relationships. A prospective, longitudinal study may have provided more insight into these relationships overtime. As a secondary data analysis, we were limited to the analysis of the measure employed in the original study. Therefore, physical function was measured by a self-report questionnaire. Future research could include objective measures of physical function for a better understanding on the impact to physical functioning in older BCS. In addition, the majority of the older BCS in this study are White (93%), which limits generalizability and the ability to address inequalities in our survivorship literature [44]. Future studies should focus on recruiting more diverse samples to ensure robust data and better understanding of racial and ethnic health-related differences [44]. Lastly, studies need to include a broader age range of older BCS to better understand the impact of age on these outcomes.

Conclusion

Overall, older BCS with fewer years of education, more self-reported comorbidities, and worse subjective cognitive function reported worse physical functioning. Older BCS in this study who reported better subjective cognitive function reported better QoL. As evidenced by this study and others, cognitive dysfunction following cancer and treatment can have an impact on the functional ability and quality of life of patients, especially in older BCS [45]. This study provides important implications for clinical practice identifying that those older BCS with cognitive dysfunction are potentially at greater risk for decreased physical functioning and/or QoL. Additionally, findings from this study provide direction for interventions which include maintenance of physical functioning and QoL and could ultimately support independent living and even mortality.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011) Healthy aging at a glance. http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/22022. Accessed 6/9/2020

Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH (2007) Role of comorbidity, symptoms and age in the health of older survivors following treatment for cancer. Aging Health 3(5):625–635. https://doi.org/10.2217/1745509X.3.5.625

Vance D, Larsen KI, Eagerton G, Wright MA (2011) Comorbidities and cognitive functioning: implications for nursing research and practice. J Neurosci Nurs 43(4):215–224. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182212a04

Mandelblatt SRA, Luta G, McGuckin M, Clapp JD, Hurria A et al (2014) Cognitive impairment in older patients with breast cancer before systemic therapy: is there an interaction between cancer and comorbidity? J Clin Oncol 32(18):1909–1918. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.2050

Mandelblatt JS, Small BJ, Luta G, Hurria A, Jim H, McDonald BC et al (2018) Cancer-related cognitive outcomes among older breast cancer survivors in the thinking and living with cancer study. J Clin Oncol 36(32):3211. https://doi.org/10.1200/Jco.18.00140

Mandelblatt JS, Clapp JD, Luta G, Faul LA, Tallarico MD, McClendon TD et al (2016) Long-term trajectories of self-reported cognitive function in a cohort of older survivors of breast cancer: CALGB 369901 (Alliance). Cancer 122(22):3555–3563. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30208

Freedman RA, Pitcher B, Keating NL, Ballman KV, Mandelblatt J, Kornblith AB et al (2013) Cognitive function in older women with breast cancer treated with standard chemotherapy and capecitabine on Cancer and Leukemia Group B 49907. Breast Cancer Res Treat 139(2):607–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2562-6

Lange M, Giffard B, Noal S, Rigal O, Kurtz JE, Heutte N et al (2014) Baseline cognitive functions among elderly patients with localised breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 50(13):2181–2189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2014.05.026

Lange M, Heutte N, Rigal O, Noal S, Kurtz JE, Levy C et al (2016) Decline in cognitive function in older adults with early-stage breast cancer after adjuvant treatment. Oncologist 21(11):1337–1348. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0014

Hurria A, Rosen C, Hudis C, Zuckerman E, Panageas KS, Lachs MS et al (2006) Cognitive function of older patients recieving aduvant chemotherapy for brast cancer: a pilot prospective longitudinal study. J Am Geriatr Soc 54(6):924–931. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00732.x

Cesari M, Onder G, Russo A, Zamboni V, Barillaro C, Ferrucci L et al (2006) Comorbidity and physical function: results from the aging and longevity study in the Sirente geographic area (ilSIRENTE study). Gerontology 52(1):24–32. https://doi.org/10.1159/000089822

Smith AW, Reeve BB, Bellizzi KM, Harlan LC, Klabunde CN, Amsellem M et al (2008) Cancer, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life of older adults. Health Care Financ Rev 29(4):41–56

Forjaz MJ, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Ayala A, Rodriguez-Rodriguez V, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Garcia-Gutierrez S, Prados-Torres A (2015) Chronic conditions, disability, and quality of life in older adults with multimorbidity in Spain. Eur J Intern Med 26(3):176–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2015.02.016

Beswick AD, Rees K, Dieppe P, Ayis S, Gooberman-Hill R, Horwood J, Ebrahim S (2008) Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 371(9614):725–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60342-6

Levasseur M, St-Cyr Tribble D, Desrosiers J (2009) Meaning of quality of life for older adults: importance of human functioning components. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 49(2):e91–e100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2008.08.013

Fagerström C, Borglin G (2010) Mobility, functional ability and health-related quality of life among people of 60 years or older. Aging Clin Exp Res 22(5–6):387–394. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03324941

Crouch A, Champion V, Von Ah D (2020) Cognitive dysfunction in older breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000896

Champion VL, Wagner LI, Monahan PO, Daggy J, Smith L, Cohee A et al (2014) Comparison of younger and older breast cancer survivors and age-matched controls on specific and overall quality of life domains. Cancer 120(15):2237–2246. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28737

Unverzagt FW, Monahan PO, Moser LR, Zhao Q, Carpenter JS, Sledge GW Jr, Champion VL (2007) The Indiana University telephone-based assessment of neuropsychological status: a new method for large scale neuropsychological assessment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 13(5):799–806. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617707071020

Rey A (1941) L’examen psychologique dans les cas d’encephalopathie traumatique. Arch Psychol 28:286–340

Geffen GM, Butterworth P, Geffen LB (1994) Test-retest reliability of a new form of the auditory verbal learning test (AVLT). Arch Clin Neuropsychol 9(4):303–316

Uchiyama CL, D’Elia LF, Dellinger AM, Becker JT, Selnes OA, Wesch JE et al (1995) Alternate forms of the Auditory-Verbal Learning Test: issues of test comparability, longitudinal reliability, and moderating demographic variables. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 10(2):133–145

Wechsler D (2014) Wechsler adult intelligence scale–Fourth Edition (WAIS–IV). Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

Tulsky DZJ, Ledbetter M (1997) WAIS-III and WMS-III Technical Manual. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

Ruff RM, Light RH, Parker SB, Levin HS (1996) Benton controlled oral word association test: reliability and updated norms. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 11(4):329–338

Ross T (2003) The reliability of cluster and switch scores for the Controlled Oral Word Association Test. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 18(2):153–164

Benton A, Hamsher K (1989) Multilingual aphasia examination. AJA Associates, Iowa City

Cimprich B, Visovatti M, Ronis DL (2011) The Attentional Function Index–a self-report cognitive measure. Psychooncology 20(2):194–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1729

Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM (1993) The rand 36-item health survey. Health Econ 2(3):217–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4730020305

Campbell A, Converse PE, Rodgers WL (1976) The Quality of American Life: perceptions, evolutions, and satisfactions. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Von Ah D, Russell KM, Storniolo AM, Carpenter JS (2009) Cognitive dysfunction and its relationship to quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 36(3):326–336. https://doi.org/10.1188/09.ONF.326-334

Cohen J (2013) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic Press, New York

Fu MR, Axelrod D, Guth AA, Cleland CM, Ryan CE, Weaver KR et al (2015) Comorbidities and quality of life among breast cancer survivors: a prospective study. J Pers Med 5(3):229–242. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm5030229

Park J, Rodriguez JL, O’Brien KM, Nichols HB, Hodgson ME, Weinberg CR, Sandler DP (2021) Health-related quality of life outcomes among breast cancer survivors. Cancer 127(7):1114–1125. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33348

Cosentino S, Devanand D, Gurland B (2018) A link between subjective perceptions of memory and physical function: implications for subjective cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis 61(4):1387–1398. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170495

Hesseberg K, Bergland A, Rydwik E, Brovold T (2016) Physical fitness in older people recently diagnosed with cognitive impairment compared to older people recently discharged from hospital. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 6(3):396–406. https://doi.org/10.1159/000447534

Mandelblatt JS, Ahn J, Small BJ, Ahles TA, Carroll JE, Denduluri N et al (2019) Symptom burden among older breast cancer survivors: the Thinking and Living With Cancer (TLC) study. Cancer 126(6):1183–1192. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32663

Biglia N, Bounous VE, Malabaila A, Palmisano D, Torta DM, D’Alonzo M et al (2012) Objective and self-reported cognitive dysfunction in breast cancer women treated with chemotherapy: a prospective study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 21(4):485–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01320.x

Sibbritt DW, Byles JE, Regan C (2007) Factors associated with decline in physical functional health in a cohort of older women. Age Ageing 36(4):382–388. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afm017

Alcock L, O’Brien TD, Vanicek N (2015) Age-related changes in physical functioning: correlates between objective and self-reported outcomes. Physiotherapy 101(2):204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2014.09.001

Gopalakrishnan N, Blane D (2008) Quality of life in older ages. B Med Bull 85(1):113–126. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldn003

Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Smith GD (2006) Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health 60(1):7–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.023531

Shaw BA, Spokane LS (2008) Examining the association between education level and physical activity changes during early old age. J Aging Health 20(7):767–787. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264308321081

Clark LT, Watkins L, Pina IL, Elmer M, Akinboboye O, Gorham M et al (2019) Increasing diversity in clinical trials: overcoming critical barriers. Curr Probl Cardiol 44(5):148–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2018.11.002

Mayo SJ, Lustberg M, Dhillon HM, Nakamura ZM, Allen DH, Von Ah D et al (2021) Cancer-related cognitive impairment in patients with non-central nervous system malignancies: an overview for oncology providers from the MASCC Neurological Complications Study Group. Support Care Cancer 29(6):2821–2840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05860-9

Acknowledgements

The first author (Adele Crouch, PhD, RN) is currently a postdoctoral fellow supported by the Precision Health Initiative grant at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis. The authors would like to acknowledge Precision Health Grand Challenge, IUPUI, PI: Shekhar; Von Ah: Scientist & Crouch: postdoctoral fellow, Co-director Behavioral-Psychosocial-Ethics Core, 07/01/20190-8/30/2021. Dr. Crouch received support for their doctoral education and for this study from National Cancer Institute #T32CA117865 (PI: Champion; Co-I: Von Ah; Pre-Doctoral Fellow: Crouch); Oncology Nursing Society Foundation Dissertation Grant (Crouch); American Cancer Society Doctoral Scholarship in Cancer Nursing (Crouch); and 2018–2020 Jonas Scholar (Crouch). The parent study was primarily funded by the American Cancer Society (Grant no. RSGPB-04-089-01, PI: Champion), which was coordinated by the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (Robert L. Comis, MD and Mitchell D. Schnall, MD, PhD, Group Co-Chairs) and supported in part by Public Health Service Grants CA189828 and CA180795 and from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Health and Human Services. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and analysis were performed by Adele Crouch, Victoria Champion, and Diane Von Ah. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Adele Crouch and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The questionnaires and methodology for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Indiana University and all cooperating sites.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

N/A; only deidentified data was analyzed and published.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Crouch, A., Champion, V.L. & Von Ah, D. Comorbidity, cognitive dysfunction, physical functioning, and quality of life in older breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 30, 359–366 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06427-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06427-y