Abstract

Background

It is unknown if the implementation of an advance care planning (ACP) program is feasible in daily clinical practice for glioblastoma patients. We aimed to develop an ACP program and assess the preferred content, the best time to introduce such a program in the disease trajectory, and possible barriers and facilitators for participation and implementation.

Methods

A focus group with health care professionals (HCPs) and individual semi-structured interviews with patients and proxies (of both living and deceased patients) were conducted.

Results

All predefined topics were considered relevant by participants, including the current situation, worries/fears, (supportive) treatment options, and preferred place of care/death. Although HCPs and proxies of deceased patients indicated that the program should be implemented relatively early in the disease trajectory, patient-proxy dyads were more ambiguous. Several patient-proxy dyads indicated that the program should be initiated later in the disease trajectory. If introduced early, topics about the end of life should be postponed. A frequently mentioned barrier for participation was that the program would be too confronting, while a facilitator was adequate access to information.

Conclusion

This study resulted in an ACP program specifically for glioblastoma patients. Although participants agreed on the program content, the optimal timing of introducing such a program was a matter of debate. Our solution is to offer the program shortly after diagnosis but let patients and proxies decide which topics they want to discuss and when. The impact of the program on several patient- and care-related outcomes will be evaluated in the next step.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With an annual incidence of approximately 3 per 100,000 persons, glioblastoma is the most common type of glioma and also the most severe subtype [1, 2]. Patients have a median survival of only 15 months, despite multimodal treatment with surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy [3].

During the course of the disease, glioma patients may experience progressive neurological deficits, such as motor deficits, seizures, and cognitive dysfunction [4,5,6,7]. Progressive cognitive decline may seriously interfere with patients’ ability to make decisions regarding treatment or care [8,9,10]. It therefore seems important to involve glioma patients early in the disease trajectory in treatment decision-making [11]. A way to achieve this is with advance care planning (ACP). ACP is a process to involve patients and their proxies at an early stage in decision-making on future (palliative) care, including end of life (EOL) care [12]. ACP allows patients and their proxies (defined as persons that are involved in the patient’s care trajectory, e.g., partner, spouse, child, parent, neighbor), together with their physicians, to evaluate all care options and to communicate their preferences. However, it is unclear what the optimal timing of introduction of such a program is [13,14,15].

An increasing body of evidence suggests that early palliative care is effective in improving mood and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of cancer patients in their EOL phase [16, 17]. ACP could be part of such an early palliative care trajectory. Furthermore, ACP has shown to improve outcomes in older patients and patients with chronic diseases, including patient/family satisfaction and the quality of EOL care, as well as a reduction in stress, anxiety, and depression in surviving proxies [18]. Also, the level of agreement between the patients’ preference for care and the actually received care increased [19].

It has been suggested that early palliative care through structured ACP, focusing on topics such as timely identification and treatment of disease-specific symptoms, could improve HRQoL of glioblastoma patients as well as symptom control [20]. Other studies showed that the majority of glioblastoma patients died at their preferred place if this was expressed [21], which was associated with increased dignity [22]. Moreover, if high-grade glioma patients expressed their EOL care preferences, these were often met (90%) [23]. Thus, ACP could potentially improve HRQoL and quality of care in glioblastoma patients [24], and a program addressing the specific needs of glioblastoma patients is warranted.

Although promising, it is unknown if the implementation of an ACP program would be feasible in daily clinical practice for glioblastoma patients. Before implementing such a program, this should be developed in such a way that it meets the needs of glioblastoma patients and their proxies [11]. The aim of this study was to develop an ACP program specifically for glioblastoma patients. To do so, we evaluated topics that are relevant for patients and their proxies, as well as practical issues including the appropriate timing of initiation of such a program in the disease trajectory, and facilitators and barriers to participate in an ACP program.

Methods

Participants

Eligible patients were adults with a histologically confirmed glioblastoma (WHO grade IV) or molecularly glioblastoma-like tumors in any stage of their disease, and/or their proxies, who visited the outpatient clinic of a large tertiary hospital (Haaglanden Medical Center, The Hague, The Netherlands, accredited as a national center of expertise for glioma patients) between September 2016 and January 2017. Patients were excluded if they did not understand the Dutch language, judged as incompetent by their treating physician (i.e., lacking capacity to consent to research), or if they previously received formal ACP. All possibly eligible patients were identified by the researcher prior to their consultation and they were asked for participation by their treating physician. In case they did not want to participate, several patient- and disease-related characteristics were recorded to assess selection bias. Moreover, healthcare professionals (HCPs) specialized in brain tumors and/or palliative care were invited to participate, as well as proxies of deceased patients (they were invited approximately 3 months after the patient’s death).

Data collection

A focus group with HCPs was conducted, as well as semi-structured interviews with patient-proxy dyads (i.e., a group of two people, in this case, the patient together with his/her proxy), a patient or proxy alone, and proxies of deceased patients. During the focus group/interviews, three topics were discussed: the preferred content of the ACP program, the optimal timing to introduce such a program, and barriers and facilitators to participate in an ACP program (an overview of the topics discussed during the semi-structured interview are presented in Supplementary File 1). The focus group was moderated by one researcher (LF), who did not participate in the discussions during the session. The semi-structured interviews were conducted by the same researcher (LF). No other HCPs were involved in the interviews, nor as being an interviewer, nor as being interviewed. Both the focus group and individual conversations were recorded.

Content semi-structured interviews

Content of ACP program

The topics discussed in the focus group and semi-structured interviews were based on a literature search and expert opinion (i.e., research team). Topics were categorized into (1) current situation, (2) worries and fears of the patient and proxy, (3) (supportive) treatment options, and (4) preferred place of care and death (Table 1). All participants were asked to indicate whether they regarded the presented topics as important to include in the ACP program, and if topics were missing.

Timing to introduce ACP

During the focus group, HCPs were requested to indicate the best moment in the disease trajectory to offer an ACP program to patients: (1) shortly after diagnosis, (2) after chemoradiation, about 12–16 weeks after diagnosis, (3) after the first three courses of adjuvant chemotherapy, approximately 6 months after diagnosis, (4) after adjuvant chemotherapy, about 9 months after diagnosis, or (5) another moment. These options were also presented to patients/proxies (this may have been hypothetical for some, as they were not in that disease stage yet), and proxies of deceased patients.

Barriers and facilitators to participate in an ACP program

Possible barriers (negative influences) and facilitators (positive influences) for participation and implementation were experienced which could be considered when optimizing implementation of and participation in the ACP program.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the participant characteristics, using IBM SPSS version 21.0. The semi-structured interviews and focus group were transcribed verbatim and analyzed thematically using the software program NVIVO 11. To assure reliability of coding, all transcripts of the interviews and focus group were coded by two researchers, and differences were resolved in consensus.

Results

Participants

Focus group

The focus group consisted of neurologists specialized in neuro-oncology (n = 2), a nurse specialist in neuro-oncology (n = 1), a nurse specialist in oncology (n = 1), radiation oncologists specialized in neuro-oncology (n = 2), a palliative nurse of a hospice (n = 1), a general practitioner (n = 1), a nursing home physician (n = 1), and a senior researcher with expertise in EOL care in different patient populations (n = 1).

Patients and proxies

We aimed to include at least five patient-proxy dyads and five proxies of deceased patients. In total, 13 patient-proxy dyads and six proxies of deceased patients were invited for participation.

Eight out of the 13 patient-proxy dyads participated. Of note, one interview was held with the patient only and one with the proxy only, and one patient-proxy dyad was interviewed separately. Most participating patients were male, with a mean age of 61, and all had a good performance status (KPS ≥ 70). Although most patients were diagnosed with glioblastoma, one patient with a molecularly glioblastoma-like tumor was included. Most proxies were female and their mean age was 57 years.

Six proxies of deceased patients were invited, of which five participated in the semi-structured interviews. Their mean age was 68 years. Proxies of deceased patients were invited to participate after a median of 6 months (range 3–7) after the death of the patient. Most of the deceased patients were male, with a mean age of 68 at the time of death, see Table 2 for the baseline characteristics of the participants.

Patients who participated in the study were not different from the patients who were eligible but declined to participate with respect to gender, tumor type, age, and performance status (data not shown).

Reasons not to participate

Five out of thirteen patient-proxy dyads who were invited for participation declined. There were various reasons for non-participation including a poor physical condition, being too early to talk about such topics, not wanting to think about these topics, considering this type of conversation too confronting, already having too much on their mind, or considering the program non-beneficial because everything was already arranged.

Content of ACP program

All participants, i.e., focus group participants, patient-proxy dyads, and proxies of deceased patients, were requested to indicate whether the proposed topics were relevant to include in the ACP program. The focus group deemed the topics of all themes as relevant. All topics within the theme “current situation” were also considered important by the patient-proxy dyads and proxies of deceased patients, particularly future perspective and the relationship with family/friends. Within the theme “worries and fears,” all topics were deemed important to include. In addition, new topics that emerged were the needs of proxies and financial problems. In general, all topics within the theme “(supportive) treatment” were found to be important by participants. One proxy of a deceased patient said she rather did not want to talk about euthanasia. Lastly, all topics within the theme “preferred place of care and death” were deemed important to discuss. However, one patient and one proxy indicated that these topics should only be discussed when the moment was there, see Table 3 for quotes of participants emphasizing the relevance of the proposed topics.

Timing of ACP program

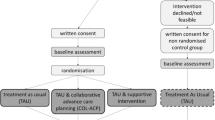

The HCPs decided, in consensus, that after chemoradiation would be the most optimal moment to offer ACP to patients. The main reason was that patients are still competent early in the disease trajectory and therefore generally able to communicate their wishes. Proxies of deceased patients indicated that the program should be offered as early as possible during the disease course; shortly after diagnosis or after chemoradiation (Fig. 1). This would prepare them sufficiently for the future.

The patients and their proxies, however, were more ambiguous. Although most patient-proxy dyads indicated that the optimal timing was early in the disease trajectory (after diagnosis or after chemoradiation), other patient-proxy dyads indicated that ACP should be offered later in the disease trajectory (after six adjuvant chemotherapy cycles or at the time that anti-tumor treatment is no longer meaningful). Of note, all choices reflected moments the patients/proxies already had experienced in the disease trajectory, indicating that they felt that those moments were appropriate.

Barriers and facilitators

Facilitators

Both patient-proxy dyads and proxies of deceased patients mentioned obtaining information, sufficient time to discuss issues, providing peace, discussing wishes, availability of an appropriate conversational partner, and the possibility to discuss certain topics as facilitators to participate in an ACP program. Other facilitators were that everything will be organized in advance, guidance during the disease trajectory, and face-to-face contact with a conversational partner and a fixed contact person.

Patient-proxy dyads also mentioned that participating in an ACP program may facilitate informing all involved disciplines on their wishes, that patients and their families are forced to think about these topics, that patients can stay in control, that proxies are strongly involved, and that help can be found timely.

Facilitators specifically mentioned by HCPs were letting patients choose the topics, patients’ awareness of the situation, and a nurse who has enough time to discuss these topics. Similar to proxy dyads and proxies of deceased patients, HCPs mentioned that facilitators to participate in an ACP program could be providing hope and/or peace, providing information, the possibility to discuss certain topics, giving patients the opportunity to arrange everything in advance, to stay in control, and a fixed contact person during the disease trajectory.

Barriers

Both patient-proxy dyads and proxies of deceased patients mentioned that not wanting to think about the proposed topics would be a barrier to participate in an ACP program. Similarly, HCPs said that patients and their proxies might not want to discuss these topics with them. Other barriers mentioned by patients/proxies were difficulties in communicating with the patient, that it may be too confronting to talk about, or overwhelming, and more practically, that it might be difficult to participate in such a program with their proxy, or that it might not be helpful if they did not have a strong connection with their conversational partner.

Patient-proxy dyads further indicated that possible barriers were that participating might cost too much time and energy and that it requires traveling to the hospital, but also that they do not want to know everything. Lastly, HCPs indicated that this type of conversations might damage the physician-patient relationship.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to develop an ACP program and assessed the preferred content of the program, the best time to introduce such a program in the disease trajectory, and possible barriers and facilitators for participation and implementation.

Participants considered all predefined topics important to discuss in an ACP program. Besides, two new topics were proposed, being the needs of proxies and financial problems. Financial problems have been recognized as important in previous studies [21] and are often included as a topic in need assessment questionnaires. Moreover, (practical) needs of proxies have been identified as important [25,26,27,28]. Indeed, the caregiver burden is found to be high and associated with cognitive deterioration of patients and changes in their personality and behavior [29]. Previous research showed that in the EOL phase, approximately 50% of caregivers indicated a high burden and feelings of stress [30]. Reasons were changes in the relationship between the patient and caregiver, an adaptation of new roles and new responsibilities [31]. Providing information and concrete advice on dealing with these everyday difficulties can benefit caregivers [32].

It has been suggested that structured ACP may provide better symptom control (through early identification of symptoms and treatment) and improvement of psychosocial support and EOL planning in brain tumor patients [20]. Our results confirm the importance of these topics. Moreover, a previous study showed that most brain tumor patients are willing to discuss ACP issues [33]. Patients in our study who were not willing to discuss EOL issues indicated that these were discussed too early, and should only be discussed when becoming relevant (i.e., if they enter the EOL phase). Whereas HCPs and proxies of deceased patients indicated that the ACP program should be offered relatively early in the disease trajectory, with proxies of deceased patients indicating that the program should even be introduced as soon as possible (i.e., shortly after diagnosis), patient-proxy dyads were more ambiguous. Several patient-proxy dyads indicated that the program should be initiated later in the disease trajectory, after adjuvant chemotherapy or even when the moment is there (i.e., at the start of the patient’s EOL phase). This is in line with previous findings that brain tumor patients did not want to discuss ACP issues shortly after diagnosis [33]. It has been suggested that it might even be inappropriate to initiate ACP during active treatment [34] because it may take away the hope of patients and their relatives. Uncertainty about the disease trajectory and lack of information regarding prognosis may influence how patients perceive the introduction of ACP [33]. In another study, the majority of palliative care patients, including cancer patients in all disease stages, felt that the best timing of introducing ACP was after disease recurrence, failure of curative treatment, or at the time it became evident that they had a poor prognosis [34]. In contrast, a study including terminally ill patients found that the best timing of introducing early palliative care was soon after diagnosis [17]. Since the timing to discuss ACP has an impact on its acceptability and effect [14, 34], it is important to choose the most appropriate moment in the disease trajectory. Although several patients in our study indicated that early implementation of ACP is not preferred, it should be considered that glioblastoma patients have an incurable disease and may experience a rapid decline in their cognition, hampering decision-making later in the disease process [9, 10]. Timely initiation of ACP seems therefore warranted in this population. Considering the preferences of all participants, the most optimal moment to introduce the ACP program seems to be relatively early in the disease trajectory, i.e., for glioblastoma patients right after chemoradiation, although the best timing remains a matter of debate, also in other diseases (e.g., dementia) [14, 21, 35, 36]. However, to meet the wishes of patients/proxies, we propose that they should be able to choose the topics they want to discuss as well as the depth of the conversation. Nevertheless, by presenting issues that could become relevant in the future, we hope to trigger patients to at least think about these topics.

Barriers and facilitators affect the acceptance of an ACP program and should therefore be considered when designing and implementing an ACP program for glioblastoma patients. In this study, an important facilitator was that it offers patients a way to timely discuss and plan their future care, thereby empowering patients and proxies. The presence of a trained neuro-oncology nurse was also believed to facilitate this process and has been acknowledged previously [33]. In contrast, participating in such a program may also be confronting for patient/proxies, thereby being an important barrier. A barrier for general practitioners (GPs) to initiate ACP in cancer patients was the limited information provided by specialists in the hospital, as well as limited contact with their patients and the continuation of anti-tumor treatment by the treating physician even when this was no longer relevant [37]. By initiating ACP in the hospital and stimulating to draft a form with the patients’ wishes and goals of care, and subsequently communicating these to the GP, the cooperation between different healthcare professionals, as well as the quality and continuity of the patient’s care, may be improved. We therefore aim to include completion of a patients’ wish form in the ACP program.

Although the results of this study may guide further research on the implementation of ACP in clinical practice for glioblastoma patients, several limitations should be considered. First, participants were from the Netherlands, and results may be different for patients in other countries, especially due to cultural and religious differences [35, 38, 39]. One example is the inclusion of the topic euthanasia, which is only applicable to certain countries [40]. Second, particularly patients with an interest in ACP may have participated in this study, hampering generalizability of the results. This also holds true for clinical practice, in which it is likely that not all patients and/or proxies are willing to participate. Nevertheless, we suggest offering this program to all patient-proxy dyads visiting the outpatient clinic, so they will know that this type of care is available whenever required. Lastly, with respect to the applied methodology, the relevance of topics was not assessed using a validated scale (e.g., Likert scale assessing the strength of relevance), but rather as “relevant” or “not relevant.” However, patients were encouraged to explain their choice. Also, not all specialists involved in the care of glioblastoma patients participated in the focus group (e.g., medical oncologist and neurosurgeon), which may have hampered the identification of all relevant issues.

In conclusion, ACP appears important for glioblastoma patients, and currently, no evidence-based ACP program specifically for this patient population exists [11, 20, 24]. The results of this study are used to develop an ACP program that meets glioblastoma patients’ needs. In addition, a strategy to implement this program will be developed. A next step would be to offer this program to glioblastoma patients and their proxies and to evaluate the impact of this program on outcomes such as HRQoL, satisfaction with care, anxiety and depression, health resource utilization, and actual received care.

References

Ho VK, Reijneveld JC, Enting RH, Bienfait HP, Robe P, Baumert BG, Visser O (2014) Changing incidence and improved survival of gliomas. Eur J Cancer 50(13):2309–2318

Thakkar JP, Dolecek TA, Horbinski C, Ostrom QT, Lightner DD, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Villano JL (2014) Epidemiologic and molecular prognostic review of glioblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 23(10):1985–1996

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U, Curschmann J, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Gorlia T, Allgeier A, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Mirimanoff RO (2005) Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 352(10):987 -96., no. 10:987–96

Behin A, Hoang-Xuan K, Carpentier AF, Delattre JY (2003) Primary brain tumours in adults. Lancet 361(9354):323–331 no. 9354:323–31

Oberndorfer S, Lindeck-Pozza E, Lahrmann H, Struhal W, Hitzenberger P, Grisold W (2008) The end-of-life hospital setting in patients with glioblastoma. J Palliat Med 11(1):26–30

Pace A, Di Lorenzo C, Guariglia L, Jandolo B, Carapella CM, Pompili A (2009) End of life issues in brain tumor patients. J Neuro-Oncol 91(1):39–43

Sizoo EM, Braam L, Postma TJ, Pasman HR, Heimans JJ, Klein M, Reijneveld JC, Taphoorn MJ (2010) Symptoms and problems in the end-of-life phase of high-grade glioma patients. Neuro-Oncology 12(11):1162–1166

Kerrigan S, Erridge S, Liaquat I, Graham C, Grant R (2014) Mental incapacity in patients undergoing neuro-oncologic treatment: a cross-sectional study. Neurology 83(6):537–541

Sizoo EM, Pasman HR, Buttolo J, Heimans JJ, Klein M, Deliens L, Reijneveld JC, Taphoorn MJ (2012) Decision-making in the end-of-life phase of high-grade glioma patients. Eur J Cancer 48(2):226–232

Triebel KL, Martin RC, Nabors LB, Marson DC (2009) Medical decision-making capacity in patients with malignant glioma. Neurology 73(24):2086–2092

Fritz L, Dirven L, Reijneveld JC, Koekkoek JA, Stiggelbout AM, Pasman HR, Taphoorn MJ (2016) Advance care planning in glioblastoma patients. Cancers 8(11):102

Andreassen P, Neergaard MA, Brogaard T, Skorstengaard MH, Jensen AB (2015) The diverse impact of advance care planning: a long-term follow-up study on patients’ and relatives’ experiences. BMJ Support Palliat Care 7(3):335-340

Laryionava K, Heussner P, Hiddemann W, Winkler EC (2015) Framework for timing of the discussion about forgoing cancer-specific treatment based on a qualitative study with oncologists. Support Care Cancer 23(3):715–721

Lovell A, Yates P (2014) Advance care planning in palliative care: a systematic literature review of the contextual factors influencing its uptake 2008-2012. Palliat Med 28(8):1026–1035

Pfeil TA, Laryionava K, Reiter-Theil S, Hiddemann W, Winkler EC (2015) What keeps oncologists from addressing palliative care early on with incurable cancer patients? An active stance seems key. Oncologist 20(1):56–61

Lorenz KA (2008) Progress in quality-of-care research and hope for supportive cancer care. J Clin Oncol 26(23):3821–3823

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363(8):733–742

Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W (2010) The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 340:c1345

Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL (2012) Effect of a disease-specific advance care planning intervention on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 60(5):946 -50

Walbert T (2014) Integration of palliative care into the neuro-oncology practice: patterns in the United States. Neurooncol Pract 1(1):3–7

Flechl B, Ackerl M, Sax C, Oberndorfer S, Calabek B, Sizoo E, Reijneveld J, Crevenna R, Keilani M, Gaiger A, Dieckmann K, Preusser M, Taphoorn MJ, Marosi C (2013) The caregivers' perspective on the end-of-life phase of glioblastoma patients. J Neuro-Oncol 112(3):403–411

Sizoo EM, Taphoorn MJ, Uitdehaag B, Heimans JJ, Deliens L, Reijneveld JC, Pasman HR (2013) The end-of-life phase of high-grade glioma patients: dying with dignity? Oncologist 18(2):198–203

Koekkoek JA, Dirven L, Reijneveld JC, Sizoo EM, Pasman HR, Postma TJ, Deliens L, Grant R, McNamara S, Grisold W, Medicus E, Stockhammer G, Oberndorfer S, Flechl B, Marosi C, Taphoorn MJ, Heimans JJ (2014) End of life care in high-grade glioma patients in three European countries: a comparative study. J Neuro-Oncol 120(2):303–310

Song K, Amatya B, Voutier C, Khan F (2016) Advance care planning in patients with primary malignant brain tumors: a systematic review. Front Oncol 6:223

Arber A, Hutson N, de Vries K, Guerrero D (2013) Finding the right kind of support: a study of carers of those with a primary malignant brain tumour. Eur J Oncol Nurs 17(1):52–58

Janda M, Eakin EG, Bailey L, Walker D, Troy K (2006) Supportive care needs of people with brain tumours and their carers. Support Care Cancer 14(11):1094–1103

McConigley R, Halkett G, Lobb E, Nowak A (2010) Caring for someone with high-grade glioma: a time of rapid change for caregivers. Palliat Med 24(5):473–479

Pace A, Dirven L, Koekkoek JAF, Golla H, Fleming J, Ruda R, Marosi C, Le Rhun E, Grant R, Oliver K, Oberg I, Bulbeck HJ, Rooney AG, Henriksson R, Pasman HRW, Oberndorfer S, Weller M, Taphoorn MJB (2017) European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) guidelines for palliative care in adults with glioma. Lancet Oncol 18(6):e330–e340

Wasner M, Paal P, Borasio GD (2013) Psychosocial care for the caregivers of primary malignant brain tumor patients. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 9(1):74–95

Faithfull S, Cook K, Lucas C (2005) Palliative care of patients with a primary malignant brain tumour: case review of service use and support provided. Palliat Med 19(7):545–550

Sizoo EM, Pasman HR, Dirven L, Marosi C, Grisold W, Stockhammer G, Egeter J, Grant R, Chang S, Heimans JJ, Deliens L, Reijneveld JC, Taphoorn MJ (2014) The end-of-life phase of high-grade glioma patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 22(3):847–857

Boele FW, Grant R, Sherwood P (2017) Challenges and support for family caregivers of glioma patients. Br J Neurosci Nurs 13(1):8–16

Song K, Amatya B, Khan F (2015) Advance care planning in patients with brain tumours: a prospective cohort study. J Cancer Res Ther 3(7):85–91

Barnes K, Jones L, Tookman A, King M (2007) Acceptability of an advance care planning interview schedule: a focus group study. Palliat Med 21(1):23–28 no. 1:23–8

Buiting HM, Rietjens JA, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Maas PJ, van Delden JJ, van der Heide A (2008) A comparison of physicians ΓÇÖ end-of-life decision making for non-western migrants and Dutch natives in the Netherlands. Eur J Pub Health 18(6):681–687

Robinson L, Dickinson C, Rousseau N, Beyer F, Clark A, Hughes J, Howel D, Exley C (2012) A systematic review of the effectiveness of advance care planning interventions for people with cognitive impairment and dementia. Age Ageing 41(2):263–269

De Vleminck A, Pardon K, Beernaert K, Deschepper R, Houttekier D, Van Audenhove C, Deliens L, Vander Stichele R (2014) Barriers to advance care planning in cancer, heart failure and dementia patients: a focus group study on general practitioners’ views and experiences. PLoS One 9(1):e84905

Menaca A, Evans N, Andrew EV, Toscani F, Finetti S, Gómez-Batiste X, Higginson IJ, Harding R, Pool R, Gysels M (2012) End-of-life care across Southern Europe: a critical review of cultural similarities and differences between Italy, Spain and Portugal. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 82(3):387–401

Gysels M, Evans N, Meñaca A, Andrew E, Toscani F, Finetti S, Pasman HR, Higginson I, Harding R, Pool R (2012) Culture and end of life care: a scoping exercise in seven European countries. PLoS One 7(4):e34188

van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Rurup ML, Buiting HM, van Delden JJ, Hanssen-de Wolf JE, Janssen AG, Pasman HR, Rietjens JA, Prins CJ, Deerenberg IM, Gevers JK, van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G (2007) End-of-life practices in the Netherlands under the Euthanasia Act. N Engl J Med 356(19):1957–1965

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating patients and their relatives for their time and effort.

Funding

The study was funded by a grant from Team Westland (crowdfunding), located in the Netherlands.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The procedures performed in this study are in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The ethical committee of the participating center approved the study.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Control of data

The authors have full control of all primary data, and we would agree to have the journal to review our data if requested.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fritz, L., Zwinkels, H., Koekkoek, J.A.F. et al. Advance care planning in glioblastoma patients: development of a disease-specific ACP program. Support Care Cancer 28, 1315–1324 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04916-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04916-9