Abstract

Purpose

In a palliative care setting, the preservation of quality of life is of particular importance. Horticultural therapy (HT) is reported as an excellent way to improve physical as well as psychological well-being, reduce levels of anxiety and depression, and promote social interaction. The use of horticultural interventions in palliative care has not yet been explored. The aim of this study was to explore the effects of HT in patients and team members on a palliative care ward.

Methods

This study was based on a qualitative methodology, comprising 20 semistructured interviews with 15 advanced cancer patients participating in HT and with 5 members of the palliative care team. Interviews were analyzed using NVivo 10 software based on thematic analysis.

Results

The results revealed the following themes: (1) well-being, (2) variation of clinical routine, (3) creation, and (4) building relationships. Patients experienced positive stimulation through HT, were distracted from daily clinical routines, enjoyed creative work, and were able to build relationships with other patients. HT was also welcomed by the members of the palliative care team. Thirty-six percent of the patients did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 45% could not participate in the second or third HT session.

Conclusions

Our study showed that the availability of HT was highly appreciated by the patients as well as by the palliative care team. Nevertheless, the dropout rate was high, and therefore, it might be more feasible to integrate green spaces into palliative care wards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families considering physical, psychosocial, and spiritual aspects [1]. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition emphasizes that the subjective quality of life of patients and their relatives plays a central role in palliative care. This multidisciplinary approach aims to accompany the patients holistically and to improve their individual quality of life.

The term “Green Care” is used to summarize initiatives that aim to benefit from the healing effects of animals, plants, and nature on humans. Green Care is considered to be health promoting, as green spaces can contribute to mental as well as physical and social health [2, 3]. Studies on restorative environments have shown that green spaces are more likely to relieve stress than interior spaces and urban areas, even though urban inhabitants enjoy better health services than rural inhabitants [4, 5]. Further studies have shown that natural environments lead to a reduction in pulse and of stress hormones as well as an improvement in mood [6]. Gardening is reported to be meaningful and restful. It has been shown that even a view of nature can improve postoperative convalescence [7].

Horticultural therapy (HT) uses the effect of experiencing gardening and nature by using natural elements. This includes activities related to plants and gardening, such as the making of flower arrangements, doing wickerwork, planting, and sowing. This suggests that direct, active contact with nature in the form of HT might improve well-being in patients. This could also work in a palliative care ward without access to green spaces. However, the use of HT in a palliative care ward has not yet been studied.

Several studies have shown that horticultural therapy is an effective treatment option in several patient fields: patients with dementia, patients with impaired mental health, elderly patients, and oncological patients [8,9,10,11]. The present qualitative study aimed to investigate how patients and palliative care team members perceive the option of HT in a hospital-based palliative care ward within a large capital city where access to a green area is not available.

Methods

Study design and data collection

This qualitative study was based on the use of semistructured interviews with predetermined open-ended questions (Table 1). The study was conducted at the palliative care ward of the Medical University of Vienna, integrated into a Comprehensive Cancer Center; the ward is a hospital-based unit consisting of 12 beds. Inclusion criteria for participating in the study were an age of over 18 years, an absence of cognitive or mental deficit, no presence of severe septicemia, no language problems, and the ability to sign written informed consent for inclusion in the study and for digital recording of the interviews. Patients who were unable to sign the informed consent declaration due to the severity of their illness or for medical reasons were excluded from the study. All members of the multidisciplinary team were asked for their willingness to participate in the current study before initiation and signed informed consent. Interviews were conducted between July 2015 and April 2017 by using open-ended questions. All participants were interviewed by a female medical student (H.T.) who was not a member of the multidisciplinary palliative care team. Caregivers or team members were not present while the interviews were conducted. The purpose of the interview was to investigate patients’ and palliative care staffs’ perceptions of integrating HT into the palliative care ward as well as to record positive and negative perceptions concerning HT in the clinical setting on the ward. As we planned a larger patient sample for participation in HT, we knew that it would not be possible for each individual to be interviewed. To achieve depth of understanding, we tried to avoid interviewing participants because they seemed particularly suitable or “easy to interview.” For that reason, we prepared sealed envelopes with “Interview YES” and “Interview NO” for each included participant and planned to continue this process until saturation was reached. The interviews were held after participation in a minimum from one to three sessions of HT. The study was conducted following the COREQ Criteria for qualitative studies [12]. Thematic analysis was applied as a theoretically flexible qualitative method that permits the description of experiences, perceptions, and views. Following the six-step model by Braun and Clarke, we adhered to the following process: (1) familiarization with the data, (2) generation of initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the report [13].

Horticultural therapy sessions

The sessions took place in a room on the palliative care ward and were conducted by a single female horticultural therapist. Patients were offered the opportunity to participate in one to three HT sessions during their stay on the palliative care ward and could be accompanied by their relatives or friends upon request. Palliative care team members were not present during HT but were in charge of picking up the patients for the sessions. Twenty-two sessions of HT took place in the period between June 2015 and April 2017, and each session lasted 2 to 3 h. Adhering to the local hygienic guidelines, no earth, seedlings, or potted flowers were used. The following activities were part of the HT sessions: making a flower arrangement, decorating a jam jar with flowers, arranging Styrofoam balls, making herbal salts, creating a bookmark from dried flowers, making a wreath and arranging a door wreath, building a flower sponge, designing a wicker basket, and lacing palm branches.

Data analysis

All participants consented to the use of interviews for the study. The interviews were conducted in German, transcribed by a professional transcriber and translated into English by a professional translator trying to avoid loss of originality. The transcripts of the interviews were not returned to the participants for correction. The interview transcriptions were analyzed by three female researchers using open coding (A.K., E.K.M., H.T.). None of the researchers had established a relationship with the study participants prior to the study. Codes emerged from an iterative process whereby the three coders coded the interview transcripts, discussed the codes, and grouped these codes into categories according to their similarity. Theoretical saturation was reached, as no primary codes emerged after the fifteenth interview, and the final codes could be determined. As analysis of the most recent interviews did not generate new codes or categories, no further interviews were conducted. Once all codes were applied, the coded data and categories were reviewed by verbal group discussion with two other researchers (F.A., M.U.), and corresponding themes were identified. Data were analyzed using NVIVO 10.0 software following thematic analysis. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (Approval No. 1034/2015).

Results

Patient characteristics

Fifteen interviews were conducted with 15 patients at the palliative care ward selected from a larger cohort of 42 (64%) out of 66 (100%) consecutive patients who participated at one to three sessions of HT; five members of the palliative care team were also interviewed, for a total of 20 interviews. Twenty-four patients (36%) did not meet the inclusion criteria and had to be excluded for the following reasons: ten (42%) suffered from severe septicemia and deteriorated performance status; eight (33%) patients did not consent to participate in the study; and in six patients (25%), delirium was present. Table 2 shows characteristics of all interviewed patients participating in HT. The patients’ demographic characteristics were as follows: eight (53%) women and seven (47%) men; median age of 66 years (range 31–87); and median Karnofsky performance status scale (KPS), on admission, of 60% (range 30–70). All patients suffered from advanced cancer. Regarding the palliative care team, all members were female, and those interviewed included the chaplain, the physiotherapist, two nurses, and the senior physician of the palliative care ward to represent the multidisciplinary team. Forty-two (100%) patients completed one, 23 (55%) patients completed two, and nine (21%) patients completed three sessions of HT. Nineteen (45%) patients could not participate in the second or third session, either because they had died or their performance status had severely deteriorated since the first session of HT. Participants included four to seven patients per HT session. The duration of the interviews ranged from 10 to 42 min (mean 22 min).

Qualitative findings

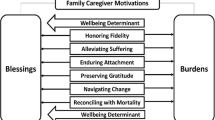

Four themes emerged from the analysis of the interviews: theme 1, well-being; theme 2, variation of clinical routine; theme 3, creation; and theme 4, building relationships. Results of the interviews are presented narratively, illustrating the themes and codes by using participants’ quotations. Figure 1 shows themes, categories, and examples for codes that were generated from the interviews.

-

Theme 1: Well-being

Seven patients reported that HT was improving the quality of their daily routine.

It was a wonderful change, I say once. And it’s a reassuring thing, for the patient this is soothing, I must say. And it is an occupation that does not hurt, does not bite, yes. It encourages one to see something green or see a few flowers. (female, aged 66 years, suffering from pancreatic cancer, participated in two sessions of HT)

Five patients reported a feeling of relaxation through working with green elements. Five patients also felt that by concentrating on HT, their symptom burden was relieved through distraction.

First of all, it was a great change. And it’s something that interests me too. Because I am not a big flower champion, but I love flowers in all variants. (female, aged 70 years, suffering from breast cancer, participated at three sessions of HT)

Three patients reported that HT reminded them of positive memories from their childhood or their own gardens at home, in forms of positive association. Three patients reported a tranquilizing effect. Four patients reported that they would prefer to get back to their own gardens or have the opportunity to have a green area in the palliative care ward. All five interviewed palliative care team members perceived HT as a novel and beneficial intervention.

-

Theme 2: Variation of clinical routine

Eight patients as well as the five team members reported that HT enriched their daily routines. HT sessions were perceived as something novel and innovative that helped the patients focus on something other than their disease.

Because you always have to face your own end and then you have a lot of time and I like to remember my youth or my childhood. So that there was only the garden with us, opening the door and we were in the garden, yes. Pleasant good change to everyday life in the hospital. (male, aged 48 years, suffering from lung cancer, participated in two sessions of HT)

Four patients mentioned that HT was a reason for them to leave their hospital bed. HT also led to distraction from burdensome symptoms, as reported by six patients.

Yes, it just took the people out of bed, they had the opportunity to think about something different and not just to be confronted with their disease. Maybe to have familiar materials in the hand, which reminded them of earlier times, or to start something new, to do something different with the family again or to talk with their family and not always think about suffering. (female, aged 85 years, suffering from colorectal cancer, participated at two sessions of HT)

This was also noticed by the palliative care team members, as they noticed that patients were motivated to leave their bedsides for a non-medical intervention and showed some signs of elevated mood. The horticultural therapist was also highly appreciated, and eight patients as well as five palliative care team members reported a friendly, attentive, welcoming atmosphere during the HT sessions.

-

Theme 3: Creation

The patients experienced a creative feeling through haptic work in the form of touching and arranging different materials. Five patients reported that they were activated through getting out of “passivity,” which led to a form of creativity. It was possible to hand out their creations to friends or relatives, which eight patients reported as positive. The ability to create something was mentioned as soothing.

I thought it was a wonderful distraction. For me, it was always great to see what creative ideas there were, yes. It was incredibly beautiful for the eye and the soul and also for the smell. So many things have smelled very well. (male, aged 57 years, suffering from gastric cancer, participated at three sessions of HT)

Three palliative care team members mentioned that their patient’ relationships were enriched through picking the patients up for the HT sessions and talking about their created works. Both patients and palliative care members perceived it as positive to see things that were created during HT as decorations on the palliative care ward.

It was positive to do something with the hands, to be creative with the colors and also smelling these flowers, which was very pleasant. And it is creative to think about, what can I do with these things? (female, aged 31 years, suffering from cervical cancer, participated in one session of HT)

-

Theme 4: Building relationships

The patients acknowledged that they got in contact with other inpatients through HT and felt a sense of sociability.

Sure it is, well, it’s just a distraction, you get to know other people. You can hear something else again, right. So I see this really only from a positive aspect. (female, aged 45, nurse of the palliative care team)

Three patients reported that they had been skeptical about “gardening together” before HT; but after participating in the sessions, they highly valued this opportunity. They got to know other inpatients, which led to a more personal atmosphere and was also appreciated by the palliative care team members.

Very positive, mentally as well as physically. We had patients in this therapy room who otherwise could hardly get out of bed. We were able to work with them through the ideas to work with flowers, but also to really work creatively and mobilize creativity at all. But mentally, there were a lot of things happening when they were sitting out together, when they got together and got to know each other. Patients who had never left their room before. Those patients made a good development, they were really enlivened and one could see that this creative work simply changed quite a lot in the patients. (female, aged 66 years, chaplain of the palliative care team)

Discussion

Our study results demonstrated a highly positive perception of HT by patients as well as by palliative care team members, and HT was perceived as valuable and enriching. Besides distracting patients from their daily clinical routines, it improved personal relationships and group cohesion and led to an elevated mood in both patients and palliative care team members. Patients felt physically activated, benefited from using haptic skills by working with different materials, and experienced creative stimulation through arranging objects such as Styrofoam balls, bookmarks, wreathes, sponges, and baskets. They were pleased to leave their daily medical routines, emerge from passivity, and get to know other inpatients.

Previous studies have shown that the general condition of patients suffering from dementia was improved when they regularly spent time in the garden [14,15,16]. Although patients suffering from dementia were excluded from the current study, this fact highlights the importance of green spaces and might also affect patients in a palliative care setting who are mentally impaired. In addition, physical and psychological well-being were significantly increased by a horticultural intervention and the effect persisted even after completion [11]. In studies of the group cohesion of patients suffering from depression, social activity was reported to be increased by HT [17]. Reduced levels of anxiety, depression, and stress were also reported [18, 19]. The above-mentioned studies suggested that HT significantly improved the quality of life in several respects. A particularly positive effect on physical and emotional well-being was shown, but also effects relating to hope and group cohesion. For this reason, HT as a so called “Vitamin G” appears to be especially promising for use in palliative care, where the preservation of quality of life is of paramount importance.

Nature has a special meaning in everyone’s lives [20]. Extending the knowledge from previous studies showing positive effects of green areas on hospital inpatients, this study demonstrated that even the use of natural materials and green elements had a positive effect on patients. In a simple way, working in a group together with other patients in the context of HT sessions had a beneficial effect on the well-being of the patients on a palliative care ward. By “bringing a garden to the palliative care ward,” the daily routine was enriched. The reason HT was beneficial to the patients might relate to the fact that it covers creative, physical, psychological, and social dimensions and therefore corresponds very well to the overall concept of palliative care. The contact with green elements can lead to distraction, release memories, and trigger a feeling of comfort. This relates to the attention restoration theory, which states that concentration may be restored by exposure to natural environments [21].

Limitations

Several limitations of the present study should also be mentioned. Patients were recruited from a single, university-based center where no green area was accessible on the palliative care ward. Therefore, it is possible that our results cannot be generalized to different settings. Thirty-six percent of the consecutive patients who were initially considered for the study did not meet the inclusion criteria, which might relate to the frailty of many patients being admitted to a palliative care ward. One third of those patients did not consent to participate, which might limit the feasibility of HT at a palliative care ward. This was confirmed by the fact that 45% of the patients could not participate in the second or third HT sessions. The fact that 15 interviewees were selected from a larger cohort of 42 patients does not necessarily make those who were selected information-rich [22]. Nevertheless, as none of the patients had been participating in HT before, our rationale was that this procedure would be the best way to gain credibility about the topic being studied.

Conclusions

The strength of our study was the novelty of our approach, as many university medical centers do not have green spaces and we therefore aimed to study this kind of approach for such spaces. All patients who participated in HT had a positive impression, and although asking for negative aspects of HT was part of the qualitative interview, no critical remarks were mentioned in the interviews. The results of this qualitative study showed that HT as an indoor intervention did benefit patients at a palliative care ward in terms of the opportunity to connect with others as well as to acquire new skills. In addition, HT was highly appreciated by the palliative care team members. Therefore, wherever it is not possible to integrate green spaces into palliative care wards or where such spaces are not accessible, HT might help contribute to the greater well-being of patients in palliative care wards.

References

Pandve HT, Fernandez K, Chawla PS, Singru SA (2009) Palliative care—need of awareness in general population. Indian J Palliat Care 15(2):162–163. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1075.58465

Groenewegen PP, van den Berg AE, de Vries S, Verheij RA (2006) Vitamin G: effects of green space on health, well-being, and social safety. BMC Public Health 6(1):149. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-149

Maas J, Verheij RA, de Vries S, Spreeuwenberg P, Schellevis FG, Groenewegen PP (2009) Morbidity is related to a green living environment. J Epidemiol Community Health 63(12):967–973. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.079038

Dye C (2008) Health and urban living. Science 319(5864):766–769. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1150198

Roe JJ, Thompson CW, Aspinall PA, Brewer MJ, Duff EI, Miller D, Mitchell R, Clow A (2013) Green space and stress: evidence from cortisol measures in deprived urban communities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 10(9):4086–4103. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10094086

Wichrowski M, Whiteson J, Haas F, Mola A, Rey MJ (2005) Effects of horticultural therapy on mood and heart rate in patients participating in an inpatient cardiopulmonary rehabilitation program. J Cardpulm Rehabil 25(5):270–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/00008483-200509000-00008

Ulrich RS (1984) View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 224(4647):420–421. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402

Fillon M Home gardening: an effective cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014 106(11). https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju391

Gonzalez MT, Hartig T, Patil GG, Martinsen EW, Kirkevold M (2011) A prospective study of existential issues in therapeutic horticulture for clinical depression. Issues Ment Health Nurs 32(1):73–81. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2010.528168

Kamioka H, Tsutani K, Yamada M, Park H, Okuizumi H, Honda T, Okada S, Park SJ, Kitayuguchi J, Abe T, Handa S, Mutoh Y (2014) Effectiveness of horticultural therapy: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med 22(5):930–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2014.08.009

Soga M, Gaston KJ, Yamaura Y (2016) Gardening is beneficial for health: a meta-analysis. Prev Med Rep 5:92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.007

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Braun V, Clarke V (2014) What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 9(1):26152. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152. eCollection 2014.

Hall J, Mitchell G, Webber C, Johnson K (2016) Effect of horticultural therapy on wellbeing among dementia day care programme participants: a mixed-methods study (Innovative Practice) Dementia 11: 1471301216643847

Noone S, Innes A, Kelly F, Mayers A (2015) ‘The nourishing soil of the soul’: the role of horticultural therapy in promoting well-being in community-dwelling people with dementia Dementia 23: 1471301215623889

Whear R, Coon JT, Bethel A, Abbott R, Stein K, Garside R (2014) What is the impact of using outdoor spaces such as gardens on the physical and mental well-being of those with dementia? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. J Am Med Dir Assoc 15(10):697–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.05.013

Gonzalez MT, Hartig T, Patil GG, Martinsen EW, Kirkevold M (2010) Therapeutic horticulture in clinical depression: a prospective study of active components. J Adv Nurs 66(9):2002–2013. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05383.x

Beyer KM, Kaltenbach A, Szabo A, Bogar S, Nieto FJ, Malecki KM (2014) Exposure to neighborhood green space and mental health: evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11(3):3453–3472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110303453

Page M (2008) Gardening as a therapeutic intervention in mental health. Nurs Times 104(45):28–30

Hartig T, Mitchell R, de Vries S, Frumkin H (2014) Nature and health. Annu Rev Public Health 35(1):207–228. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443

Ohly H, White MP, Wheeler BW, Bethel A, Ukoumunne OC, Nikolaou V, Garside R (2016) Attention restoration theory: a systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 19(7):305–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/10937404.2016.1196155

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K (2015) Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Admin Pol Ment Health 42(5):533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna. The study was performed in cooperation with the University College for Agrarian and Environmental Pedagogy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Masel, E.K., Trinczek, H., Adamidis, F. et al. Vitamin “G”arden: a qualitative study exploring perception/s of horticultural therapy on a palliative care ward. Support Care Cancer 26, 1799–1805 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3978-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3978-z