Abstract

Introduction

The relationship between the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) and its industry partners has been longstanding, productive technologically, and beneficial to patient care and education. In order to both maintain this important relationship to honor its responsibility to society for increasing transparency, SAGES established a Conflict of Interest Task Force (CITF) and charged it with identifying and managing potential conflicts of interest (COI) and limiting bias at the SAGES Annual Scientific Meetings. The CITF developed and implemented a comprehensive process for reporting, evaluating, and managing COI in accordance with (and exceeding) Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education guidelines.

Methods

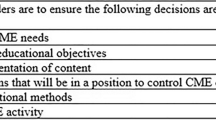

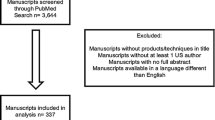

From 2011 to 2013, all presenters, moderators, and session chairs received proactive and progressively increasing levels of education regarding the CITF rationale and processes and were required to disclose all relationships with commercial interests. Disclosures were reviewed and discussed by multiple layers of reviewers, including moderators, chairs, and CITF committee members with tiered, prescribed actions in a standardized, uniform fashion. Meeting attendees were surveyed anonymously after the annual meeting regarding perceived bias. The CITF database was then analyzed and compared to the reports of perceived bias to determine whether the implementation of this comprehensive process had been effective.

Results

In 2011, 68 of 484 presenters (14 %) disclosed relationships with commercial interests. In 2012, 173 of 523 presenters (33.5 %) disclosed relationships, with 49 having prior review (9.4 %), and eight required alteration. In 2013, 190 of 454 presenters disclosed relationships (41.9 %), with 93 presentations receiving prior review (20.4 %), and 20 presentations were altered. From 2008 to 2010, the perceived bias among attendees surveyed was 4.7, 6.2, and 4.4 %; and in 2011–2013, was 2.2, 1.2, and 1.5 %.

Conclusion

It is possible to have a surgical meeting that includes participation of speakers that have industry relationships, and minimize perceived bias.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rothman DJ, McDonald WJ, Berkowitz CD, Chimonas SC, DeAngeles CD, Hale RW, Nissen SE, Osborn JE, Scully JH, Thomson GE, Wofsy D (2009) Professional medical associations and their relationships with industry: a proposal for controlling conflict of interest. JAMA 301:1367–1372

Lo B, Ott C (2013) What is the enemy in CME, conflicts of interest or bias? JAMA 310:1019–1020

ACCME Financial relationships and conflicts of interests. http://www.accme.org/requirements/accreditation-requirements-cme-providers/policies-and-definitions/financial-relationships-and-conflicts-interest. Accessed 24 Mar 2014

ACCME 2012 Annual Report. http://www.accme.org/sites/default/files/630_2012_Annual_Report_20130724_2.pdf. Accessed 24 March 2014

Council of Medical Specialty Society Code for Interactions with Companies. http://www.cmss.org/codeforinteractions.aspx. Accessed 24 March 2014

PhRMA Code on Interactions with Health Care Professionals. http://www.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/phrma_marketing_code_2008-1.pdf. Accessed 24 March 2014

AdvaMed Code on Interactions with Health Care Professionals. http://advamed.org/res.download/112. Accessed 24 March 2014

Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (2010) Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) statement on the relationship between professional medical associations and industry. Surg Endosc 24:742–744

Litynski GS (1999) Endoscopic surgery: the history, the pioneers. World J Surg 23:745–753

Keune JD, Vig S, Hall BL, Matthews BD, Klingensmith ME (2011) Taking disclosure seriously: disclosing financial conflicts of interest at the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 212:215–224

Steinbrook R (2011) Industry payments to physicians: lessons from orthopedic surgery. Comments on financial payments by orthopedic device makers to orthopedic surgeons. Arch Intern Med 171:1765–1766

Harris G, Carey B (2008) Researchers fail to reveal full drug pay. New York Times. June 8, p A1

Chimonas S, Stahl F, Rothman DJ (2012) Exposing conflict in psychiatry: does transparency matter? Int J Law Psychiatry 35:490–495

Lo B, Field MJ (2009) Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice. National Academies Press, Washington

Lewin J, Arend TE (2011) Industry and the profession of medicine: balancing appropriate relationships with the need for innovation. Soc Vasc Surg 54(3 Suppl):47S–49S

Sade RM (2011) The American Association for Thoracic Surgery Ethics Committee and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Standards and Ethics Committee. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 142:12–17

American Society of Clinical Oncology (2013) American Society of Clinical Oncology policy for relationships with companies: background and rationale. J Clin Oncol 16:2037–2042

Schofferman JA, Eskay-Auerbach ML, Sawyer LS, Herring SA, Arnold PM, Muelhlbauer EF (2013) Conflict of interest and professional medical associations: the North American Spine Society experience. Spine J 13:874–979

Turnipseed W (2010) Industrial relations with academic health care and professional associations: what’s all the fuss? Who cares anyway? Surgery 148:613–617

Minter RM, Angelos P, Coimbra R, Dale P, de Vera ME, Hardacre J, Hawkins W, Kirkwood K, Matthews JB, McLoughlin J, Peralta E, Schmidt M, Ahou W, Schwarze (2011) Ethical management of conflict of interest: proposed standards for academic surgical societies. J Am Coll Surg 213:677–682

Disclosures

Steven C. Stain, MD: United Healthcare Gastrointestinal Advisory Board (Honoraria). Erin Schwarz: BSC Management (Employment). Phillip Shadduck, MD: Allergan Medical (Consulting). Paresh C. Shah: Stryker Endoscopy (Consulting), Olympus Endoscopy (Consulting), Endoevolution (Consulting), Zmed Technologies (Consulting). Sharona B. Ross: Olympus (Research, Consulting), Covidien (Research). Yumi Hori: BSC Management (Employment). Patricia Sylla: Olympus (Consulting), Covidien (Consulting), Applied Medical (Teaching).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stain, S.C., Schwarz, E., Shadduck, P.P. et al. A comprehensive process for disclosing and managing conflicts of interest on perceived bias at the SAGES annual meeting. Surg Endosc 29, 1334–1340 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3571-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3571-1