Abstract

Background

Diaphragmatic hernias may be congenital or acquired (traumatic). Some patients present in adulthood with a congenital hernia undetected during childhood or due to trauma, known as the adult-onset type. The authors present their series of adult-onset type diaphragmatic hernias managed successfully by laparoscopy.

Methods

This study retrospectively investigated 21 adult patients between 1995 and 2007 who underwent laparoscopic repair at the authors’ institution, 15 of whom were symptomatic. Laparoscopic repair was performed with mesh for 18 patients and without mesh for three patients who had Morgagni hernia.

Results

In this series, Bochdalek hernia (n = 12), Morgagni hernia (n = 3), eventration (n = 3), and chronic traumatic hernia (n = 3) were treated. Intercostal drainage was required for 14 patients, whereas in three cases the hypoplastic lung never reinflated even after surgery. The time of discharge was in the range of postoperative days 4 to 9. The complication rate was 19%, and mortality rate was 4.5%. One case of recurrence was noted after 10 months.

Conclusion

The controversies involved are the surgical approach, management of the hernial sac, whether or not to suture the defect, and choice of prosthesis. Although laparoscopic and thoracoscopic approaches are comparable, the laparoscopic approach seems to have certain distinct advantages. The authors prefer not to excise the hernial sac and favor suturing the defects before mesh reinforcement. Regarding the type of mesh used, composite, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE), or polypropylene are the available options. Laparoscopic repair is feasible, effective, and reliable. It could become the gold standard in the near future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Congenital diaphragmatic hernias (CDH) occur when the muscular entities of the diaphragm fail to develop normally, resulting in displacement of abdominal components into the thorax [1]. Bochdalek hernias (posterolateral defects) make up the majority of CDH cases. Morgagni hernia (anterior midline—foramen of Morgagni) is a less common type, occurring in only 5–10% of cases, with 90% of cases involving the right side [2]. Blunt and penetrating traumas cause most of the acquired diaphragmatic hernias [3].

The majority of patients with CDH present early in life rather than later. However, a subset of patients (5–10%) may present in adulthood with a congenital hernia undetected during childhood [4]. This study essentially deals with this subset of patients. To date, only a few reports in the literature describe a series of these patients treated by laparoscopy. Others are mostly case reports. We present a fairly large series of patients with diaphragmatic hernias managed successfully by laparoscopy and discuss its advantages.

Materials and methods

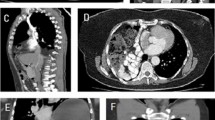

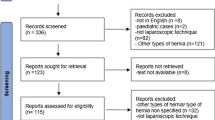

Between 1995 and 2007, 21 adult patients underwent laparoscopic diaphragmatic repair. Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia was present in 12 patients, Morgagni hernia in 3 patients, eventration in 3 patients, and chronic traumatic hernia in 3 patients. Overall, 11 patients were symptomatic, and the common symptoms were vomiting, upper abdominal pain, breathing difficulty, and retrosternal discomfort. Of these patients, two had frank respiratory distress with low oxygen saturation at admission, and one female patient was pregnant when she visited the outpatient department. Two of the three patients with Morgagni hernia had upper abdominal pain, whereas one patient was asymptomatic. Two of the patients with chronic diaphragmatic hernia had experienced a road traffic accident many years ago but currently were asymptomatic. The three patients with eventration were asymptomatic, and the condition was discovered on a chest X-ray or ultrasonogram performed for other reasons. As part of the preoperative workup, CT scan was performed for all patients, which quite clearly confirmed the diaphragmatic hernia (Fig. 1). Barium meal study was done in select patients for academic interest only. Laparoscopic intervention was planned for all the patients after they obtained anesthetic fitness.

Procedure

Pneumoperitoneum was achieved via a Veress needle, and intraabdominal pressure was maintained at 10 mmHg. The head end of the patient was raised to 25° to facilitate falling away of the bowels from the upper abdomen to occupy the pelvis. The monitor was placed at the head end of the patient directly opposite the chief surgeon. The camera assistant stood at the right of the patient, whereas the scrub nurse and another assistant stood at the patient’s left side.

A total of five ports were placed in the abdomen: a 10-mm port just above the umbilicus, a 5-mm port (right working hand) in the left midclavicular line, a 5-mm port (left working hand) in the right midclavicular line, a 5-mm port (for liver retraction) in the epigastrium, and a 5-mm port in the left midclavicular line below the level of the umbilicus (for bowel retraction).

At laparoscopy, the defects of Morgagni and Bochdalek were visualized first (Fig. 2A and B, arrows). Figure 3 shows a rare right-sided Bochdalek defect with a transverse colon as contents. The left lateral segment of the liver was retracted anteriorly with a 5-mm flexible retractor. The intraabdominal pressure was maintained at 10 mmHg to allow easy reduction of the hernial contents.

The bowels were retracted caudally with a nontraumatic grasper. The contents of the hernial sac consisted of the stomach, omentum, transverse colon, small bowel, pancreas, or spleen, differing in each case (Fig. 4). Rarely, the left kidney was found in the hernial sac (Fig. 5). These contents were gently reduced using a nontraumatic bowel-holding grasper. Special care was taken to handle the reduction of the spleen from the sac to avoid hemorrhage.

No ischemia or gangrene of the organs was found in the sac in any patient. The laparoscope was introduced into the left pleural cavity. A hypoplastic lung (Fig. 6a) was seen in one case and a collapsed lung in four cases of the large left-sided Bochdalek type (Fig. 6b). An intercostal drainage tube was inserted into the left pleural cavity under vision. The area around the defect was cleared of adhesions with ultrasonic shears to gain space for fixation of the mesh. For large defects, we have had to mobilize the splenic flexure, Gerota’s fascia of the left kidney, the left triangular ligament, and the left lobe of the liver.

The hernial sac was completely dissected out for four patients at the beginning of our experience, although we no longer perform this dissection. The left hemidiaphragm was hypotrophic in five patients with large defects. In cases of large and redundant sacs, excision of the excess sac alone was performed. For the three patients with eventration of the diaphragm, plication of the diaphragm was performed by double-breasting with several 1.0 polypropylene intracorporeal sutures (Fig. 7). This plication reduced the “highly placed” diaphragm to the normal level. The hernial defects were closed in all our patients with intracorporeal sutures using 1.0 polypropylene before placement of the mesh (Fig. 8).

Next, a 15 × 15-cm mesh was shaped and placed so as to cover the entire left or right hemidiaphragm. It was fixed with interrupted 1.0 polypropylene stitches (Fig. 9).

Gastric volvulus (Fig. 10) was present in three patients. For these cases, in addition to diaphragmatic repair, a gastropexy was performed by fixation of the stomach to the lateral abdominal wall with a few seromuscular sutures.

Results

According to our results (Table 1a), the Bochdalek type hernia was the most common, with the Morgagni type, eventration, and chronic traumatic type of diaphragmatic hernia sharing equal incidence. This study investigated 16 men and 5 women with a mean age of 42.5 years (Table 1b). Left-sided lesions were more common than right or central lesions (Table 1c).

The most common contents of the hernial sac were the stomach, colon, and small bowel, found in 14 (66.6%) patients (Table 1d). The mean size of the hernial defect was 48.5 cm2 for the Bochdalek hernias and 31.5 cm2 for the chronic traumatic hernias (Table 2). In two patients, the spleen occupied the sac in addition to the bowels. The sac was additionally occupied by the pancreas in one case, and one patient had the left kidney inside the sac. Three patients (14%) had gastric volvulus: two associated with Bochdalek hernia and one associated with eventration.

It also was noted that the patients with volvulus had a longer operating time and hospital stay. The total operating time was in the range of 82–145 min, and the perioperative bleeding was negligible.

Four patients experienced postoperative complications (Fig. 11): three cases of pneumonitis and one case of deep vein thrombosis, all managed conservatively. An intercostal tube was inserted in five patients with large hernias (Bochdalek type). These five patients had postoperative breathing difficulty and needed ventilatory support in the intensive care unit for 72 h. Postoperative chest X-rays showed a hypoplastic left lung in all patients who did not reinflate even after seven postoperative days (PODs). They were weaned off the ventilator after confirmation of adequate respiratory effort and oxygen saturation. The intercostal tube was removed between PODs 3 and 6 depending on the quantity of fluid draining from the pleural cavity. The collapsed lung never recovered postoperatively in any patient. The patient with preoperative respiratory distress due to a large Bochdalek hernia and hypoplastic left lung never recovered from anesthesia and could not be weaned. Consequently, the ventilatory support was continued up to POD 8, when the patient finally died.

For the three patients with associated volvulus, oral liquids were allowed on POD 4 and a solid diet the next day. For all the other patients, oral liquids were started on POD 1. The day of discharge was in the range of POD 4–9.

All the symptomatic patients were completely relieved of their symptoms. The patients were followed up for a mean of 24 months (range: 6–42 months). One patient (4.7%) experienced recurrence, confirmed by computed tomography (CT) scan, 10 months after surgery. This patient underwent diaphragmatic repair for Bochdalek hernia without mesh early in our series. For this case, we performed a laparoscopic mesh repair, and at this writing, there has been no re-recurrence. The conversion rate was zero, the complication rate 19%, and the mortality rate 4.7% (1/21).

Discussion

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia was first described in 1679 by Lazarus Riverius, who incidentally noted a CDH during postmortem examination of a 24-year-old person [5]. Late-onset CDH is designated as the adult type of diaphragmatic hernia [6]. Acquired hernias are traumatic in nature and considered to be the adult type. Motor vehicle accidents and penetrating trauma from gunshots and stab wounds comprise the major etiologies of diaphragmatic rupture.

Traumatic rupture of the diaphragm requires surgical intervention whether the patient presents immediately or some time after the trauma [7]. In our series, Bochdalek hernias had an incidence of 58%, Morgagni hernias an incidence of 14%, chronic traumatic hernias an incidence of 14%, and eventration an incidence also of 14%.

Since the first successful repair of CDH in 1929, great strides have been made in the management of CDH. Traditionally, the management of diaphragmatic hernias has been accomplished by laparotomy, laparoscopy, or thoracoscopy. Laparoscopic repair of diaphragmatic hernia was first reported by Campos and Sipes [8] in 1991 and immediately afterward by Kuster et al. [9] in 1992. Since then, collective experience has been growing steadily worldwide [10, 11].

Diaphragmatic hernia repair may be approached through the chest or the abdomen depending on the experience of the surgeon. The advantage of a thoracic approach is that reduction of the hernial contents can be easily achieved aided by the pneumothorax, with a hypoplastic lung providing better vision.

Schaarschmidt et al. [12] reported a technique in which a thoracoscopic inflation-assisted reduction of the thoracic contents was performed. These authors further state that this technique offers a more physiologic access to congenital diaphragmatic hernia than laparoscopy or laparotomy. However, the drawback of such techniques is the inability to identify bowel injury consequent to the reduction of contents because visibility of the peritoneal cavity is limited through a thoracoscopic approach.

Laparoscopically, the hernial contents can be reduced safely under vision in a controlled manner aided by lowering of the intraabdominal pressure. Also, because the thoracic wall is unyielding, it is difficult to manipulate instruments within the pleural cavity, making suturing cumbersome. Moreover, the defect cannot be reinforced with an adequately sized mesh, which is a risk factor for recurrence [13].

With the laparoscopic approach, the manipulation of instruments is easy because the abdominal cavity expands considerably due to pneumoperitoneum. Although the overall results of both thoracoscopy and laparoscopy are comparable, the approach of choice is a matter of personal preference and expertise [14]. In the absence of randomized studies comparing the two approaches, the ideal technique still is elusive. Esmer et al. [15] reported a combined technique using both thoracoscopy and laparoscopy to repair diaphragmatic hernias.

The three areas of controversy in the management of diaphragmatic hernias, regardless of the approach, are management of the hernial sac, whether to suture the defect or not, and the choice of prosthesis. We performed sac excision for the first five patients of our series but have now largely abandoned this procedure. Sac dissection is cumbersome, time consuming, and associated with a high risk of pleural injury [16]. With Morgagni hernias, there is the added danger of injury to the superior epigastric vessels during dissection of the sac [17, 18].

Although seroma formation in the remnant sac is a theoretical risk, most surgeons prefer to leave the sac behind, as proved by a study in which a CT scan taken 30 days postoperatively showed complete disappearance of the sac [19]. Some authors have reported the use of prosthetic material to bolster the repair, whereas other authors describe simple suturing of the defect. However, it is generally agreed that defects larger than 20–30 cm2 need a prosthesis [20, 21]. Because the traumatic (chronic) and Morgagni hernias usually have smaller defects, suturing alone will suffice [22, 23].

In all our patients, the defect size was 20 cm2 or more, so we performed both suturing and prosthetic reinforcement for the larger defects and simple suturing alone for the smaller defects (Morgagni type). We believe that suturing of the defect strengthens it to some extent, but more importantly, it restores the normal anatomy of the diaphragm and preserves the domain of the peritoneal and thoracic cavities. Primary repair of the defect and reinforcement with mesh are the main advantages of a laparoscopic approach. Suturing of large defects has the advantage of providing a flat surface for placement of the mesh, preventing mesh extrusion through the defect [24].

After suturing the defect, we always reinforce the defect with a mesh. The placement of the mesh on the peritoneal aspect of the diaphragm amounts to an “intraperitoneal onlay” type of repair and is more physiologic because the intraabdominal pressure keeps the mesh opposed to the defect (Laplace’s law), thereby reinforcing the defect. Although no randomized trials have compared the efficacy of the different types of commercially available meshes, polypropylene is known to induce excessive bowel adhesions without a peritoneal cover [25].

We used polypropylene mesh for the first 3 patients, composite mesh for 11 patients, and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) mesh for 4 patients. This choice was random depending on the availability of the meshes.

Conditions such as eventration that become symptomatic months or years after the primary injury also can be repaired laparoscopically or thoracoscopically [26]. The exact incidence of eventration is not known, but increasing numbers of cases are reported in the recent literature. Although patients with eventration have no distinct hernial defect, some form of repair is warranted, even when the defect is discovered accidentally [27]. This repair can be performed with or without mesh reinforcement or with the use of endostaplers [28, 29].

We encountered three patients with eventration and performed repair using a combination of double-breasting and mesh reinforcement. The double-breasting is a form of plication that flattens the redundant diaphragm and provides an adequate “bed” for placement and fixation of the mesh.

The association between gastric volvulus and diaphragmatic hernia is known and well documented [30]. In our series, three patients had associated gastric volvulus without evidence of gangrene. A gastropexy in these cases was added to the diaphragmatic hernia repair to prevent recurrence of the volvulus.

Another interesting laparoscopic diaphragmatic hernia repair in our series was successfully performed for a pregnant patient in 1998 [31]. She became symptomatic during the second trimester of pregnancy, probably because of the increasing intraabdominal pressure. Initially, the obstetrician attributed her symptoms to the pregnancy itself. She was referred to us for a consultation. We performed an ultrasonogram and chest X-ray, which showed a left-sided diaphragmatic hernia.

Adult congenital diaphragmatic hernias, eventration, and chronic traumatic diaphragmatic hernias are uncommon entities that often are technically challenging to repair, each presenting unique obstacles to the minimally invasive approach. However, with proper training and equipment, most of the diaphragmatic hernias are amenable to laparoscopic repair. Furthermore, patients can expect the same well-known benefits of minimal access surgery, with a recurrence rate similar to that for the open approach.

Laparoscopic surgery is a promising alternative to thoracotomy or laparotomy. We prefer to suture the defect before prosthetic reinforcement, with double-breasting in the case of eventration. The current understanding is that the type of mesh is of no particular importance, although either a composite or an ePTFE mesh probably is ideal. Fixation is best achieved with intracorporeal sutures rather than mechanical fixation devices. The presence of gastric volvulus is not a contraindication to laparoscopy.

Conclusion

Although experience is still limited, laparoscopic repair is a safe and effective method for managing adult diaphragmatic hernias and eventration. In addition to the routine benefits of minimal access surgery, such as an excellent view of the surgical field and access to it, the return of pulmonary function to normalcy is earlier than with the open method. Laparoscopy has the potential to become the gold standard for the management of adult diaphragmatic hernias in the near future.

References

Taskin M, Zengin K, Unal E, Eren D, Korman U (2002) Laparoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernias. Surg Endosc 16:869

Chang TH (2004) Laparoscopic treatment of Morgagni–Larrey hernia. W V Med J 100:14–17

Alimoglu O, Eryilmaz R, Sahin M, Ozsoy MS (2004) Delayed traumatic diaphragmatic hernias presenting with strangulation. Hernia 8:393–396

Thoman DS, Hui T, Phillips EH (2002) Laparoscopic diaphragmatic hernia repair. Surg Endosc 16:1345–1349

Al-Emadi M, Helmy I, Nada MA, Al-Jaber H (1999) Laparoscopic repair of Bochdalek hernia in an adult. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 9:423–425

Caprotti R, Mussi C, Scaini A, Angelini C, Romano F (2005) Laparoscopic repair of a Morgagni–Larrey hernia. Int Surg 90:175–178

Meyer G, Hüttl TP, Hatz RA, Schildberg FW (2000) Laparoscopic repair of traumatic diaphragmatic hernias. Surg Endosc 14:1010–1014

Campos LI, Sipes EK (1991) Laparoscopic repair of diaphragmatic hernia. J Laparoendosc Surg 1:369–373

Kuster GG, Kline LE, Garzo G (1992) Diaphragmatic hernia through the foramen of Morgagni: laparoscopic repair case report. J Laparoendosc Surg 2:93–100

Ramachandran CS, Arora V (1999) Laparoscopic transabdominal repair of hernia of Morgagni–Larrey. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 9:358–361

Rozmiarek A, Weinsheimer R, Azzie G (2005) Primary thoracoscopic repair of diaphragmatic hernia with pericostal sutures. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 15:667–669

Schaarschmidt K, Strauß J, Kolberg-Schwerdt A, Lempe M, Schlesinger F, Jaeschke U (2005) Thoracoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia by inflation-assisted bowel reduction in a resuscitated neonate: a better access? Pediatr Surg Int 21:806–808

Becmeur F, Jamali RR, Moog R, Keller L, Christmann D, Donato L et al (2005) Thoracoscopic treatment for delayed presentation of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in the infant: a report of three cases. Surg Endosc 15:1163–1166

Nguyen TL, Le AD (2006) Thoracoscopic repair for congenital diaphragmatic hernia: lessons from 45 cases. J Pediatr Surg 41:1713–1715

Esmer D, Álvarez-Tostado J, Alfaro A, Carmona R, Salas M (2007) Thoracoscopic and laparoscopic repair of complicated Bochdalek hernia in adult. Hernia. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0293-5

Liem NT (2003) Thoracoscopic surgery for congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a report of nine cases. Asian J Surg 26:210–212

Ipek T, Altinli E, Yuceyar S, Erturk S, Eyuboglu E, Akcal T (2002) Laparoscopic repair of a Morgagni–Larrey hernia: report of three cases. Surg Today 32:902–905

Percivale A, Stella M, Durante V, Dogliotti L, Serafini G, Saccomani G, Pellicci R (2005) Laparoscopic treatment of Morgagni–Larrey hernia: technical details and report of a series. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 15:303–307

Mullins ME, Saini S (2005) Imaging of incidental Bochdalek hernia. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 26:28–36

Rice GD, O’Boyle CJ, Watson DI, Devitt PG (2001) Laparoscopic repair of Bochdalek hernia in an adult. Aust N Z J Surg 71:443–445

Kitano Y, Lally KP, Lally PA (2005) Congenital diaphragmatic hernia study group: late-presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 40:1839–1843

Brusciano L, Izzo G, Maffettone V, Rossetti G, Renzi A, Napolitano V et al (2003) Laparoscopic treatment of Bochdalek hernia without the use of a mesh. Surg Endosc 7:1497–1498

Frantzides CT, Carlson MA, Pappas C, Gatsoulis N (2002) Laparoscopic repair of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia in an adult. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 10:287–290

Palanivelu C, Jani KV, Senthilnathan P, Parthasarathi R, Madhankumar MV, Malladi VK (2002) Laparoscopic sutured closure with mesh reinforcement of incisional hernias. Hernia 11:223–228

Shah S, Matthews BD, Sing RF, Heniford BT (2000) Laparoscopic repair of a chronic diaphragmatic hernia. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 10:182–186

Kim DH, Hwang JJ, Kim KD (2007) Thoracoscopic diaphragmatic plication using three 5-mm ports. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 6:280–281

Mouroux J, Venissac N, Leo F, Alifano M, Guillot F (2005) Surgical treatment of diaphragmatic eventration using video-assisted thoracic surgery: a prospective study. Ann Thorac Surg 79:308–312

Di Giorgio A, Cardini CL, Sammartino P, Sibio S, Naticchioni E (2006) Dual-layer sandwich mesh repair in the treatment of major diaphragmatic eventration in an adult. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 132:187–189

Moon S-W, Wang Y-P, Kim Y-W, Shim S-B, Jin W (2000) Thoracoscopic plication of diaphragmatic eventration using endostaplers. Ann Thorac Surg 70:299–300

Harinath G, Senapati PS, Pollitt MJK, Ammori BJ (2002) Laparoscopic reduction of an acute gastric volvulus and repair of a hernia of Bochdalek. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 12:180–183

Palanivelu C, Rajan PS, Sendhilkumar K, Parthasarathi R (1998) Laparoscopic correction of acute gastric volvulus and repair of diaphragmatic hernia performed in a pregnant lady. Surg Endosc 12:765

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Palanivelu, C., Rangarajan, M., Rajapandian, S. et al. Laparoscopic repair of adult diaphragmatic hernias and eventration with primary sutured closure and prosthetic reinforcement: a retrospective study. Surg Endosc 23, 978–985 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-008-0294-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-008-0294-1