Abstract

There is increasing recognition that Henoch-Schonlein purpura may present in an atypical form in which gastrointestinal symptoms may predominate, and classic cutaneous changes may be delayed or absent. This may lead to significant diagnostic delay. We report the case of a 9-year-old girl who presented acutely with life-threatening gastrointestinal haemorrhage from multiple intestinal sites, with no skin rash and only mild evidence of renal involvement. Henoch-Schonlein purpura was confirmed by finding IgA deposition on vessels within gastric and duodenal mucosa, while immunohistochemistry also identified dense focal T cell infiltration in gastric mucosa and within duodenal epithelium. After initial stabilisation, the patient became shocked due to further gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Isotope bleeding scan identified multiple bleeding sites. Her endoscopically confirmed gastritis was sufficiently severe to preclude corticosteroids, and she was thus treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. This therapy induced prompt and sustained resolution of symptoms, and she has remained well since. Our patient’s response concords with previous reports in corticosteroid-resistant cases to suggest that severe intestinal Henoch-Schonlein purpura may respond preferentially to intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy. In severe cases where there is significant gastritis, IVIG provides an effective alternative to corticosteroids that may be employed as first-line therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Henoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP), an immune-mediated systemic vasculitis has an estimated incidence in European children of 22.1/100,000/year, with peak incidence between 4 and 6 years of age [7]. Characteristic symptoms and signs include palpable purpuric rash, abdominal pain, arthralgia and nephritis [3, 20]. Gastrointestinal signs and symptoms, including colicky abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or bleeding, occur in 30% of cases or more, although serious complications such as intussusception, perforation, or obstruction are unusual [20]. However, massive and potentially life-threatening gastrointestinal haemorrhage may occasionally occur [1, 25].

There have been recent reports of atypical HSP in which sometimes severe renal or gastrointestinal lesions occur before or without the skin rash, causing significant diagnostic difficulty [5, 6, 8, 15, 21, 23]. We present a patient with atypical HSP who suffered life-threatening massive gastrointestinal haemorrhage from multiple intestinal sites, in whom IVIG infusion rapidly induced resolution of all abnormalities.

Materials and methods

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using standard techniques, as previously described [22]. Primary antibodies included T cell markers (CD3, 4 and 8) and HLA-DR (Dako, Ely, UK). FITC-conjugated antibodies were used to study the distribution of IgA, IgG and IgM (Dako), while C1q was localised with a polyclonal antibody (Dako) followed by TRITC-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody. Sulphated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) were localised by specific histochemistry using poly-lysine gold at pH 1.2, as previously described [16], and HSPG was localised using monoclonal 10E4 (Seikagaku, Abingdon, UK).

Clinical presentation

A previously well 9-year-old girl presented with pallor, dizziness and abdominal pain, developing severe haematemesis and melaena. There was no history of URTI, rash, arthralgia, drug ingestion or allergy. Examination showed one oral aphthous ulcer, but no other skin lesions. She was tachycardic but normotensive, anaemic with Hb 4.7 g/dl, and had normal clotting. CRP was normal (1 mg/l), serum albumin reduced at 29 g/l and creatinine 45 μmol/l. Urinalysis was not available due to oliguria. She was transfused and treated with octreotide infusion (5 μg/kg/h). Upper endoscopy showed diffuse severe oozing haemorrhagic gastritis, while histology showed patchy chronic gastritis, but no H. pylori. Urease (CLO) test for H. pylori was also negative.

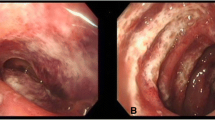

Treatment was initiated using sucralfate and intravenous omeprazole. Despite this, she bled again two days later, becoming shocked despite transfusion, octreotide and tranexamic acid, and her haemoglobin dropped from 10.2 to 5.5 g/dl. Investigations showed increased CRP (124 mg/l) and IgG (24.5 g/l, normal range 8–16 g/l), without elevation of IgA or IgM (both 0.6 g/l), while albumin had dropped to 24 g/l. Urgent isotope red cell scan showed bleeding at several sites, including stomach, small intestine and colon (Fig. 1). As urinalysis now demonstrated proteinuria and haematuria, a clinical diagnosis of HSP was made despite the absence of skin rash. As we considered corticosteroids contraindicated by severe gastritis, she was commenced on IVIG therapy at 2 g/kg/day. The bleeding terminated abruptly, and she has remained well since (over 2 years). All other investigations performed, including extensive virological screening, stool culture and microscopy, autoimmune panel and coeliac serology were normal. Repeated endoscopy showed resolving gastritis and mild duodenitis. Urgent immunohistochemical analysis, performed due to diagnostic uncertainty, showed focal subepithelial clusters of CD4 T cells in the stomach, while CD8 intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) were densely increased in the duodenum (Fig. 2). There was extensive extracellular IgA deposition in both stomach and duodenum, localising on small vessel endothelium (Fig. 2). Further evidence of vascular activation included HLA-DR expression and HSPG loss in small vessel endothelium. There was focal subepithelial IgG deposition in stomach and duodenum, partially co-localising with C1q. Epithelial expression of HSPG and sulphated GAGs were reduced in both stomach and duodenum (Fig. 2), and likely to induce intestinal protein leak as these strongly anionic molecules represent a constitutive charged barrier to albumin leakage in the intestine [4, 16].

Mucosal findings in stomach and duodenum. a Gastric histology (original magnification, ×10) showing blood within the lumen, and relatively mild inflammatory infiltrate around the epithelium. b Higher power view (×40) showing infiltration of small dark mononuclear cells around the gastric epithelium. c Staining for CD3 T cells in gastric antrum, showing dense focal aggregation beneath the surface epithelium. These were predominantly CD4+ on serial section. d Focal deposition of IgG beneath the gastric epithelium. This partially co-localised with complement C1q on serial section. e Dense staining for IgA within gastric mucosa, with IgA deposition on endothelium of small vessels. f Duodenal biopsy (×10), showing villous blunting and patchy infiltration of mononuclear cells into the lamina propria and epithelium. g Focal IgA deposition on vascular endothelium within the duodenal lamina propria. h Distribution of sulphated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs—brown staining) within the duodenum, showing scanty expression on surface epithelium (×10). i A duodenal villus (×40), showing absent sulphated GAGs on the endothelium of a small vessel. This is indicative of vascular activation, and HLA-DR expression was also upregulated (not shown). j Dense increase in CD3+ T cells within the duodenal surface epithelium. k Serial section to j and l, stained for CD4+ cells, showing few CD4+ intraepithelial lymphocytes. l Serial section to j and k, stained for CD8+ T cells, showing that the majority of the intraepithelial lymphocytes were CD8 cells

Discussion

This patient presented with severe multifocal gastrointestinal haemorrhage associated with mucosal IgA deposition and a massive increase in duodenal IELs. The dense IgA deposition on mucosal vessels, with concomitant renal involvement, are diagnostic of HSP [3, 20]. Previous reports of atypical HSP with predominant gastrointestinal involvement have shown that skin rash may develop late or indeed never appear [5, 6, 8, 15, 21, 23]. For our patient, we speculate that successful response to IVIG may have terminated her disease before skin lesions could develop. We learned that life-threatening intestinal complications of HSP may develop without skin rash, and emphasise the importance of urinalysis for proteinuria and haematuria in cases of unexplained gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

The pathogenesis of HSP shares features with IgA nephropathy, including reduced IgA1 glycosylation, possibly pathogen-induced [3, 20]. This predisposes to circulating IgA immune complexes, usually deposited in kidney, skin or gut [20]. The antigenic content of these complexes suggests possible derivation from gut contents, including dietary proteins such as gliadin [14]. Gastrointestinal lesions in HSP are characterised by focal vascular IgA deposition [12, 24], as in this case, and the formation of IgA anti-endothelial antibodies may occur [20]. The cytokine centrally involved in the isotype shift of mucosal B cells to IgA is transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) [17]. It is thus notable that a polymorphism causing high TGF-β production is associated with HSP [27], and increased circulating TGF-β-producing Th3 cells have been identified in acute HSP with gastrointestinal and not renal involvement [26]. By contrast, polymorphisms for interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-1 receptor antagonist genes have been associated with renal, but not gastrointestinal, involvement [2].

Most cases of HSP resolve spontaneously, but in severe or complicated cases several immunomodulatory therapies have been used successfully, including corticosteroids, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine and plasmapheresis [2, 20]. We faced a therapeutic dilemma, as our patient had life-threatening multifocal gastrointestinal haemorrhage, but with severe gastritis, which we considered precluded the use of steroids. We chose IVIG on the basis of efficacy in other vasculitides, and noted prompt and complete cessation of her multifocal enteric bleeding. Similar prompt resolution of gastrointestinal HSP has been reported in a 56-year-old man with bloody diarrhoea [9], and in a 19-year-old man [19], a 10-year-old boy [13] and a 5-year-old girl [10] whose chronic abdominal HSP symptoms were unresponsive to corticosteroids. Important recent evidence identifies the central mechanism of action of IVIG to be sialylation of immunoglobulin Fc regions, altering interaction with Fc-γ receptors [11]. Whether such IVIG-induced glycosylation may extend to correcting the undersialylation of IgA1 characteristic of HSP [2, 20] is an intriguing question that warrants further study. While the response of renal HSP to IVIG may be less striking [18], consistent reports of a prompt gastrointestinal response to IVIG therapy suggest that this should be considered as an important therapeutic option in cases of HSP with severe abdominal symptoms.

Abbreviations

- HSP:

-

Henoch-Schonlein purpura

- HSPG:

-

heparan sulphate proteoglycans

- GAGs:

-

glycosaminoglycans

- IL-1β:

-

interleukin-1β

- TGF-β:

-

transforming growth factor-β

- CRP:

-

c-reactive protein

- IEL:

-

intraepithelial lymphocyte

- IVIG:

-

intravenous immunoglobulin

- URTI:

-

upper respiratory tract infection

References

Agha FP, Nostrant TT, Keren DF (1986) Leucocytoclastic vasculitis (hypersensitivity angiitis) of the small bowel presenting with severe gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol 81:195–198

Amoli MM, Calvino MC, Garcia-Porrua C, Llorca J, Ollier WE, Gonzalez-Gay MA (2004) Interleukin 1β gene polymorphism association with severe renal manifestations and renal sequelae in Henoch-Schonlein purpura. J Rheumatol 31:295–298

Ballinger S (2003) Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Curr Opin Rheumatol 15:591–594

Bode L, Murch S, Freeze HH (2006) Heparan sulfate plays a central role in a dynamic in vitro model of protein-losing enteropathy. J Biol Chem 281:7809–7815

Chesler L, Hwang L, Patton W, Heyman MB (2000) Henoch-Schonlein purpura with severe jejunitis and minimal skin lesions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 30:92–95

Fitzgerald J (2000) HSP—without P? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 30:5–7

Gardner-Medwin JM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, Southwood TR (2002) Incidence of Henoch-Schonlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet 360:1197–1202

Gunasekaran TS, Berman J, Gonzalez M (2000) Duodenojejunitis: is it idiopathic or is it Henoch-Schonlein purpura without the purpura? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 30:22–28

Hamidou MA, Pottier M, Dupas B (1996) Intravenous immunoglobulin in Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Ann Intern Med 125:1013–1014

Heldrich FJ, Minkin S, Gatdula CL (1993) Intravenous immunoglobulin in Henoch-Schonlein purpura: a case study. Md Med J 42:577–579

Kaneko Y, Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV (2006) Anti-inflammatory activity of immunoglobulin G resulting from Fc sialylation. Science 313:670–673

Kato S, Ebina K, Sato S, Maisawa S, Nakagawa H (1996) Intestinal IgA deposition in Henoch-Schonlein purpura with severe gastrointestinal manifestations. Eur J Pediatr 155:91–95

Lamireau T, Rebouissoux L, Hehunstre JP (2001) Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for severe digestive manifestations of Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Acta Paediatr 90:1081–1082

Moja P, Quesnel A, Resseguier V, Lambert C, Freycon F, Berthoux F, Genin C (1998) Is there IgA from gut mucosal origin in the serum of children with Henoch-Schonlein purpura? Clin Immunol Immunopathol 86:290–297

Mrusek S, Kruger M, Greiner P, Kleinschmidt M, Brandis M, Ehl S (2004) Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Lancet 363:1116

Murch SH, Winyard PJD, Koletzko S, Wehner B, Cheema HA, Risdon RA, Phillips AD, Meadows N, Klein NJ, Walker-Smith JA (1996) Congenital enterocyte heparan sulphate deficiency is associated with massive albumin loss, secretory diarrhoea and malnutrition. Lancet 347:1299–1301

Park SR, Lee JH, Kim PH (2001) Smad3 and Smad4 mediate transforming growth factor-β1-induced IgA expression in murine B lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol 31:1706–1715

Rostoker G, Desvaux-Belghiti D, Pilatte Y, Petit-Phar M, Philippon C, Deforges L, Terzidis H, Intrator L, Andre C, Adnot S (1995) Immunomodulation with low-dose immunoglobulins for moderate IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Preliminary results of a prospective uncontrolled trial. Nephron 69:327–334

Ruellan A, Khatibi M, Staub T, Martin T, Storck D, Christmann D (1997) Purpura rheumatoïde et immunoglobulines intraveineuses. Rev Méd Interne 18:727–729

Saulsbury F (2001) Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Curr Opin Rheumatol 13:35–40

Sharieff GQ, Francis K, Kuppermann N (1997) Atypical presentation of Henoch-Schoenlein purpura in two children. Am J Emerg Med 15:375–377

Torrente F, Anthony A, Heuschkel RB, Thomson MA, Ashwood P, Murch SH (2004) Focal enhanced gastritis in regressive autism with features distinct from Crohn’s and Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol 99:598–605

Trujillo H, Gunasekaran TS, Eisenberg GM, Pojman D, Kallen R (1996) Henoch-Schonlein purpura: a diagnosis not to be forgotten. J Fam Pract 43:495–498

Uchiyama K, Yoshida N, Mizobuchi M, Higashihara H, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T (2002) Mucosal IgA deposition in Henoch-Schonlein purpura with duodenal ulcer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 17:728–729

Weber TR, Grosfeld JL, Bergstein J, Fitzgerald J (1983) Massive gastric hemorrhage: an unusual complication of Henoch-Schonlein purpura. J Pediatr Surg 18:576–578

Yang YH, Huang MT, Lin SC, Lin YT, Tsai MJ, Chiang BL (2000) Increased transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-secreting T cells and IgA anti-cardiolipin antibody levels during acute stage of childhood Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Clin Exp Immunol 122:285–290

Yang YH, Lai HJ, Kao CK, Lin YT, Chiang BL (2004) The association between transforming growth factor-β gene promoter C-509T polymorphism and Chinese children with Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Pediatr Nephrol 19:972–975

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Drs Fagbemi and Torrente contributed equally to this report, and should be considered as joint first authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fagbemi, A.A.O., Torrente, F., Hilson, A.J.W. et al. Massive gastrointestinal haemorrhage in isolated intestinal Henoch-Schonlein purpura with response to intravenous immunoglobulin infusion. Eur J Pediatr 166, 915–919 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-006-0337-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-006-0337-3