Abstract

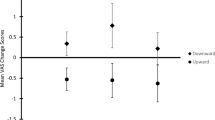

The self-serving bias is the tendency to consider oneself in unrealistically positive terms. This phenomenon has been documented for body attractiveness, but it remains unclear to what extent it can also emerge for own body size perception. In the present study, we examined this issue in healthy young adults (45 females and 40 males), using two body size estimation (BSE) measures and taking into account inter-individual differences in eating disorder risk. Participants observed pictures of avatars, built from whole body photos of themselves or an unknown other matched for gender. Avatars were parametrically distorted along the thinness–heaviness dimension, and individualised by adding the head of the self or the other. In the first BSE task, participants indicated in each trial whether the seen avatar was thinner or fatter than themselves (or the other). In the second BSE task, participants chose the best representative body size for self and other from a set of avatars. Greater underestimation for self than other body size emerged in both tasks, comparably for women and men. Thinner bodies were also judged as more attractive, in line with standard of beauty in modern western society. Notably, this self-serving bias in BSE was stronger in people with low eating disorder risk. In sum, positive attitudes towards the self can extend to body size estimation in young adults, making own body size closer to the ideal body. We propose that this bias could play an adaptive role in preserving a positive body image.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the psychometric estimates task, BSE blocks for self and other were counterbalanced and this meant that half of the participants in our study completed the judgment on the self after the judgment on the other. Hence, exposure to the other person’s body could, in principle, have influenced the subsequent rating on the self. To assess whether this influence occurred we ran explorative analyses that considered block order (self-first vs. other-first) as a factor. Specifically, we repeated the ANCOVAs described in the Analyses section adding block order (self-first vs. other-first) as a between-participant factor. None of these analyses revealed a significant main effect or interaction involving block order (all ps > 0.17). It should be remarked that the other person shown in the video was selected to be in the normal BMI range and of average attractiveness. Hence, unlike previous works (e.g., Cazzato et al., 2016) we did not use thin or overweight others that could trigger comparison judgments. Furthermore, it is important to note that our methods of constant stimuli entailed the presentation of an equal number of thinner/fatter distortions of the other. This could have also contributed to cancel out any potential bias related to seeing the other’s body before judging the self. Because our participants could differ in BMI with respect to the neutral other, we also repeated the analyses reported above, replacing EDR, with the participant’s BMI as a covariate. For PSE and body size attractiveness, none of these analyses revealed a significant main effect or interaction involving the block order variable (all ps > 0.11). For the Direct choice task, a main effect of block order (F(1, 69) = 5.91, p = 0.02, \(\eta _{{\text{p}}}^{2}\) = 0.08) and the interaction between block order and BMI (F(1, 69) = 7.10, p = 0.01, \(\eta _{{\text{p}}}^{2}\) = 0.09) reached significance. Critically, however, these effects of block order did not involve the Target variable, ps > 0.17. All other effect involving block order, ps > 0.14.

In our experimental design we counterbalanced the experimenter’s gender across participants (see Procedure section). To ascertain any potential influence of this factor on our dependent variables we also repeated the ANCOVAs described in the Analyses section adding Experimenter’s Gender as a between-participants factor, separately for each of our main dependent variables (BSE: PSE and direct choice; body size attractiveness). For the PSE we only found a main effect of Experimenter’s Gender, F(1, 69) = 5.65, p = 0.02, \(\eta _{{\text{p}}}^{2}\) = 0.08. Participants tested by the male experimenter generally underestimated more (M = − 7.40%, SD = 5.53) compared to those tested by the female experimenter (M = − 4.12%, SD = 4.64). Importantly, however, the Experimenter’s Gender did not interact with the other factors (all p > .10), indicating that this counterbalanced variable did not influence the SSB in male or female participants (i.e., there was no thee way interaction between Experimenter’s Gender, Participants’ Gender and Target; p = 0.12). For the Direct choice task, all main effects or interactions involving Experimenters’ Gender were not significant (all ps > 0.24, except for a marginal main effect of Experimenters’ Gender, F(1, 69) = 3.35, p = 0.07, \(\eta _{{\text{p}}}^{2}\) = 0.05). For body size attractiveness, we found a main effect of Experimenter’s Gender, F(1, 69) = 4.71, p = 0.03, \(\eta _{{\text{p}}}^{2}\) = 0.06. Participants tested by the male experimenter generally preferred thinner body distortions (M = − 13.40%, SD = 6.82) compared to those tested by the female experimenter (M = − 12.43%, SD = 7.16). The interaction between the Experimenters’ Gender interaction and EDR, F(1, 69) = 5.71, p = 0.02, \(\eta _{{\text{p}}}^{2}\) = 0.08, suggested that preference for thinner body distortions increased as EDR increases in those tested by the female experimenter, b = − 0.27, β = − 0.38, p = 0.02, but not in those tested by the male experimenter, b = 0.18, β = 0.31, p = 0.06. All other ps > .22 (except for a marginal interaction effect between Target and Experimenters’ Gender, F(1, 69) = 3.45, p = 0.07, \(\eta _{{\text{p}}}^{2}\) = 0.05).

After the direct choice task was performed on self and other, a direct body estimate was also repeated for the experimenter’s body. In this case, the Target factor included three levels: self, other and experimenter. The main effect of Target, F(2,138) = 8.01, p < 0.001, \(\eta _{{\text{p}}}^{2}\) = 0.10, showed that both experimenters (M = − 13.56%, SD = 9.89) were underestimated more than the self (M = − 5.96%, SD = 9.71) or the other (M = − 5.66%, SD = 7.58), ps < .001. Target interacted with EDR, F(2,138) = 4.71, p = 0.01, \(\eta _{{\text{p}}}^{2}\) = 0.06. EDR predicted body size estimation for the self (linear regression: b = 0.25, β = 0.28, p = 0.01; Figure 3d) but not for the other (linear regression: b = −.12, β = − 0.17, p = 0.14; Figure 3e) nor for the experimenters (linear regression: b = 0.001, β = 0.002, p = 0.99). Finally, Target interacted also with participants’ Gender, F(2,138) = 3.89, p = 0.02, \(\eta _{{\text{p}}}^{2}\) = 0.05. Women and men did not give different judgement for the self (women: M = − 7.03%, SD = 10.63; men: M = − 4.92%, SD = 8.73), p = 0.35, and the experimenter (women: M = − 12.76%, SD = 10.52; men: M = − 14.33%, SD = 9.31), p = 0.49, while women underestimated more the other seen in the video (M = − 7.68%, SD = 7.11) compare to men (M = − 3.69%, SD = 7.59), p = 0.02. Finally, both experimenters were judged thinner than the self and the other, ps < 0.02. All other ps > 0.09.

The correlation between the difference in BSE for self and other (i.e., our measure of SSB) and eating disorder risk remained significant even when controlling for Self-objectification (psychometric estimates: r = 0.44, p < 0.001; direct choice: r = 0.39, p = 0.001), Body surveillance (psychometric estimates: r = 0.45, p < 0.001; direct choice: r = 0.36, p = 0.001), Body shame (psychometric estimates: r = 0.42, p < 0.001; direct choice: r = 0.38, p = 0.001) and PACS (psychometric estimates: r = 0.47, p < 0.001; direct choice: r = 0.39, p < 0.001).

References

Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (1981). Depression, nondepression, and cognitive illusions: Reply to Schwartz. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 110(3), 436–447.

Alleva, J., Jansen, A., Martijn, C., Schepers, J., & Nederkoorn, C. (2013). Get your own mirror: Investigating how strict eating disordered women are in judging the bodies of other eating disordered women. Appetite, 68, 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.04.015.

Blanke, O., & Metzinger, T. (2009). Full-body illusions and minimal phenomenal selfhood. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.10.003.

Cacciari, E., Milani, S., Balsamo, A., Spada, E., Bona, G., Cavallo, L., Cerutti, F., Gargantini, L., Greggio, N., Tonini, G., & Cicognani, A. (2006). Italian cross-sectional growth charts for height, weight and BMI (2 to 20 year). Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 29(7), 581–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03344156.

Cazzato, V., Mian, E., Mele, S., Tognana, G., Todisco, P., & Urgesi, C. (2016). The effects of body exposure on self-body image and esthetic appreciation in anorexia nervosa. Experimental Brain Research, 234(3), 695–709. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-015-4498-z.

Cazzato, V., Mian, E., Serino, A., Mele, S., & Urgesi, C. (2015). Distinct contributions of extrastriate body area and temporoparietal junction in perceiving one’s own and others’ body. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 15(1), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-014-0312-9.

Cazzato, V., Siega, S., & Urgesi, C. (2012). “What women like”: influence of motion and form on esthetic body perception. Frontiers in psychology, 3, 235. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00235.

Cho, A., & Lee, J. H. (2013). Body dissatisfaction levels and gender differences in attentional biases toward idealized bodies. Body Image, 10(1), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.09.005/.

Cordes, M., Vocks, S., Düsing, R., Bauer, A., & Waldorf, M. (2016). Male body image and visual attention towards oneself and other men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 17(3), 243. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000029.

Cornelissen, K. K., Bester, A., Cairns, P., Tovée, M. J., & Cornelissen, P. L. (2015). The influence of personal BMI on body size estimations and sensitivity to body size change in anorexia spectrum disorders. Body Image, 13, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.01.001.

Cornelissen, K. K., Cornelissen, P. L., Hancock, P. J., & Tovée, M. J. (2016). Fixation patterns, not clinical diagnosis, predict body size over-estimation in eating disordered women and healthy controls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(5), 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22505.

Crossley, K. L., Cornelissen, P. L., & Tovée, M. J. (2012). What is an attractive body? Using an interactive 3D program to create the ideal body for you and your partner. PLoS One, 7(11), e50601. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050601.

Epley, N., & Whitchurch, E. (2008). Mirror, mirror on the wall: Enhancement in self-recognition. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(9), 1159–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208318601.

Farrell, C., Lee, M., & Shafran, R. (2005). Assessment of body size estimation: A review. European Eating Disorders Review, 13(2), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.622.

Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E. (2011). Social psychological theories of disordered eating in college women: Review and integration. Clinical psychology review, 31(7), 1224–1237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.011.

Fredrickson, B. L., Roberts, T. A., Noll, S. M., Quinn, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (1998). That swimsuit becomes you: Sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 269.

Gardner, R. M. (1996). Methodological issues in assessment of the perceptual component of body image disturbance. British Journal of Psychology, 87(2), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1996.tb02593.x.

Gardner, R. M., & Brown, D. L. (2014). Body size estimation in anorexia nervosa: A brief review of findings from 2003 through 2013. Psychiatry Research, 219(3), 407–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.06.029.

Garner, D. M. (2004). EDI 3: Eating disorder inventory-3: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

Garner, D. M., Garfinkel, P. E., Schwartz, D., & Thompson, M. (1980). Cultural expectations of thinness in women. Psychological Reports, 47(2), 483–491. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1980.47.2.483.

Giannini, M., Pannocchia, P., Dalle Grave, R., Muratori, F., & Viglione, V. (2008). Eating disorder inventory-3. Firenze: Giunti OS.

Jansen, A., Smeets, T., Martijn, C., & Nederkoorn, C. (2006). I see what you see: The lack of a self-serving body-image bias in eating disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45(1), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X50167.

Jansen, A. T. M., Nederkoorn, C., & Mulkens, S. (2005). Selective visual attention for ugly and beautiful body parts in eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(2), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.01.003.

Jones, D. C., & Crawford, J. K. (2005). Adolescent boys and body image: Weight and muscularity concerns as dual pathways to body dissatisfaction. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(6), 629–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-8951-3.

Lindner, D., Tantleff-Dunn, S., & Jentsch, F. (2012). Social comparison and the ‘circle of objectification’. Sex Roles, 67(3–4), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0175-x.

McCabe, M. P., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2004). Body image dissatisfaction among males across the lifespan: A review of past literature. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56(6), 675–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00129-6.

McKinley, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale development and validation. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 20(2), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00467.x.

Mezulis, A. H., Abramson, L. Y., Hyde, J. S., & Hankin, B. L. (2004). Is there a universal positivity bias in attributions? A meta-analytic review of individual, developmental, and cultural differences in the self-serving attributional bias. Psychological Bulletin, 130(5), 711–747. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.711.

Mian, E., & Gerbino, W. (2009). Body image assessment in the computer aided psychological support for eating disorders. Front. Neuroeng. Conference Abstract: Annual CyberTherapy and CyberPsychology 2009 conference. https://doi.org/10.3389/conf.neuro.14.2009.06.067.

Mohr, C., Porter, G., & Benton, C. P. (2007). Psychophysics reveals a right hemispheric contribution to body image distortions in women but not men. Neuropsychologia, 45(13), 2942–2950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.06.001.

Moussally, J. M., Rochat, L., Posada, A., & Van der Linden, M. (2017). A database of body-only computer-generated pictures of women for body-image studies: Development and preliminary validation. Behavior Research Methods, 49(1), https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0703-7.

Mussap, A. J., McCabe, M. P., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2008). Implications of accuracy, sensitivity, and variability of body size estimations to disordered eating. Body image, 5(1), 80–90.

Øverås, M., Kapstad, H., Brunborg, C., Landrø, N. I., & Lask, B. (2014). Memory versus perception of body size in patients with anorexia nervosa and healthy controls. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(2), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2276.

Prins, N., & Kingdom, F. A. A. (2009) Palamedes: Matlab routines for analyzing psychophysical data. http://www.palamedestoolbox.org.

Roefs, A. J., Jansen, A. T. M., Moresi, S. M. J., Willems, P. J. B., van Grootel, S., & van der Borgh, A. (2008). Looking good. BMI, attractiveness bias and visual attention. Appetite, 51(3), 552–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.008.

Sand, L., Lask, B., Høie, K., & Stormark, K. M. (2011). Body size estimation in early adolescence: Factors associated with perceptual accuracy in a nonclinical sample. Body Image, 8(3), 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.03.004.

Schneider, W., Eschman, A., & Zuccolotto, A. (2012a). E-prime user’s guide. Pittsburgh: Psychology Software Tools, Inc.

Schneider, W., Eschman, A., & Zuccolotto, A. (2012b). E-prime reference guide. Pittsburgh: Psychology Software Tools, Inc.

Smeets, M. A., & Kosslyn, S. M. (2001). Hemispheric differences in body image in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29(4), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.1037.

Stefanile, C., Pisani, E., Matera, C., & Guiderdoni, V. (2010). Insoddisfazione corporea, comportamento alimentare e fattori di influenza socioculturale in adolescenza. Paper presented at the VIII Convegno Nazionale SIPCO Problemi umani e sociali della convivenza, http://www.sipco.it/download/attiSIPCO%20univ.pdf.

Strelan, P., & Hargreaves, D. (2005). Women who objectify other women: The vicious circle of objectification? Sex Roles, 52(9), 707–712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-3737-3.

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.193.

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1991). The physical appearance comparison scale. The Behavior Therapist, 14, 174.

Tovée, M. J., Reinhardt, S., Emery, J. L., & Cornelissen, P. L. (1998). Optimum body-mass index and maximum sexual attractiveness. The Lancet, 352(9127), 548. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79257-6.

Vocks, S., Legenbauer, T., Rüddel, H., & Troje, N. F. (2007). Static and dynamic body image in bulimia nervosa: Mental representation of body dimensions and biological motion patterns. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20336.

Wiseman, C. V., Gray, J. J., Mosimann, J. E., & Ahrens, A. H. (1992). Cultural expectations of thinness in women: An update. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199201)11:1.

World Health Organization/Europe (2017). Body mass index—BMI. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi.

World Medical Association. (2013). WMA declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/.

Yzerbyt, V. Y., Muller, D., & Judd, C. M. (2004). Adjusting researchers’ approach to adjustment: On the use of covariates when testing interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(3), 424–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2003.10.001.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Trento e Rovereto (IT), Bando giovani ricercatori 2014 to M.M. We would like to thank Fabio La Russa who helped with data collection, Andrea Zignoli and Anna Colombatto who acted “the other” in the videos.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors of the present article declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants ware approved by the Ethical Committee at the University of Trento (Protocol 2015-013), comply with the Italian Association of Psychology ethical standards and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent

All participants provided informed consent before participation and were fully debriefed after their sessions

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mazzurega, M., Marisa, J., Zampini, M. et al. Thinner than yourself: self-serving bias in body size estimation. Psychological Research 84, 932–949 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-018-1119-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-018-1119-z