Abstract

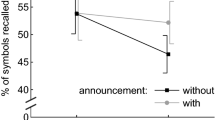

In this study, we have investigated the influence of available attentional resources on the dual-task costs of implementing a new action plan and the influence of movement planning on the transfer of information into visuospatial working memory. To approach these two questions, we have used a motor–memory dual-task design in which participants grasped a sphere and planned a placing movement toward a left or right target according to a directional arrow. Subsequently, they encoded a centrally presented memory stimulus (4 × 4 symbol matrix). While maintaining the information in working memory, a visual stay/change cue (presented on the left, center or right) either confirmed or reversed the planned movement direction. That is, participants had to execute either the prepared or the re-planned movement and finally reported the symbols at leisure. The results show that both, shifts of spatial attention required to process the incongruent stay/change cues and movement re-planning, constitute processing bottlenecks as they both reduced visuospatial working memory performance. Importantly, the spatial attention shifts and movement re-planning appeared to be independent of each other. Further, we found that the initial preparation of the placing movement influenced the report pattern of the central working memory stimulus. Preparing a leftward movement resulted in better memory performance for the left stimulus side, while the preparation of a rightward movement resulted in better memory performance for the right stimulus side. Hence, movement planning influenced the transfer of information into the capacity-limited working memory store. Therefore, our results suggest complex interactions in that the processes involved in movement planning, spatial attention and visuospatial working memory are functionally correlated but not linked in a mandatory fashion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Spiegel, Koester, Weigelt & Schack (2012) found no effects of re-planning on execution time. A possible explanation relates to the modality of the stay/change cue which was visuospatial here and auditory in the study by Spiegel, et al. (2012). This higher processing demand in the visuospatial domain (visuospatial WM stimulus and visuospatial stay/change cue) seemed to result in prolonged re-programming times and/or slower placing movements (from the present data it is not possible to differentiate between the two possibilities). Depending on the methodological approach reported in the literature, changing a movement plan sometimes results in longer execution times (e.g., Castiello, Bennett, & Chambers, 1998; Hughes et al., 2012; Paulignan, Jeannerod, MacKenzie, & Marteniuk, 1991; Stelmach, Castiello, & Jeannerod, 1994) and sometimes it does not (e.g., de Jong, 1995; Desmurget et al., 1996; Spiegel, et al., 2012; van Donkelaar & Franks, 1991).

References

Allport, D. (1987). Selection for action: Some behavioural and neurophysiological considerations of attention and action. In H. Heuer & A. Sanders (Eds.), Perspectives on perception and action (pp. 395–419). Hillsdale, New York: Erlbaum.

Anllo-Vento, L. (1995). Shifting attention in visual space: the effects of peripheral cueing on brain cortical potentials. The International Journal of Neuroscience, 80(1–4), 353–370.

Awh, E., Anllo-Vento, L., & Hillyard, S. A. (2000). The role of spatial selective attention in working memory for locations: evidence from event-related potentials. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12(5), 840–847.

Awh, E., Armstrong, K. M., & Moore, T. (2006). Visual and oculomotor selection: links, causes and implications for spatial attention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(3), 124–130.

Awh, E., & Jonides, J. (2001). Overlapping mechanisms of attention and spatial working memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5(3), 119–126.

Awh, E., Jonides, J., & Reuter-Lorenz, P. A. (1998). Rehearsal in spatial working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 24(3), 780–790.

Awh, E., Smith, E., & Jonides, J. (1995). Human rehearsal processes and the frontal lobes: PET evidence. In J. Grafman, K. Holyoak, & F. Boller (Eds.), Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (Vol. 769, pp. 97–119)., Structure and functions of the human prefrontal cortex New York: New York Academy of Sciences.

Baddeley, A. D. (1986). Working Memory. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory: looking back and looking forward. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4(10), 829–839.

Baker, K. S., Mattingley, J. B., Chambers, C. D., & Cunnington, R. (2011). Attention and the readiness for action. Neuropsychologia, 49(12), 3303–3313. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.08.003.

Baldauf, D., & Deubel, H. (2010). Attentional landscapes in reaching and grasping. Vision Research, 50(11), 999–1013. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2010.02.008.

Baldauf, D., Wolf, M., & Deubel, H. (2006). Deployment of visual attention before sequences of goal-directed hand movements. Vision Research, 46(26), 4355–4374.

Bathurst, K., & Kee, D. W. (1994). Finger-tapping interference as produced by concurrent verbal and nonverbal tasks: an analysis of individual differences in left-handers. Brain and Cognition, 24(1), 123–136.

Belopolsky, A. V., & Theeuwes, J. (2012). Updating the premotor theory: the allocation of attention is not always accompanied by saccade preparation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 38(4), 902–914. doi:10.1037/a0028662.

Benwell, C. S., Harvey, M., Gardner, S., & Thut, G. (2012). Stimulus- and state-dependence of systematic bias in spatial attention: additive effects of stimulus-size and time-on-task. Cortex; a Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior,. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2011.12.007.

Bleckley, M., Durso, F., Crutchfield, J., Engle, R., & Khanna, M. (2003). Individual differences in working memory capacity predict visual attention allocation. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 10(4), 884–889.

Bundesen, C. (1990). A theory of visual attention. Psychological Review, 97(4), 523–547.

Bunting, M. F., & Cowan, N. (2005). Working memory and flexibility in awareness and attention. Psychological Research, 69(5–6), 412–419. doi:10.1007/s00426-004-0204-7.

Carrier, L. M., & Pashler, H. (1995). Attentional limits in memory retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 21(5), 1339–1348.

Castiello, U., Bennett, K., & Chambers, H. (1998). Reach to grasp: the response to a simultaneous perturbation of object position and size. Experimental Brain Research, 120(1), 31–40.

Chum, M., Bekkering, H., Dodd, M. D., & Pratt, J. (2007). Motor and visual codes interact to facilitate visuospatial memory performance. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(6), 1189–1193.

Chun, M. (2011). Visual working memory as visual attention sustained internally over time. Neuropsychologia, 49(6), 1407–1409. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.01.029.

Collins, T., Heed, T., & Roder, B. (2010). Visual target selection and motor planning define attentional enhancement at perceptual processing stages. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 14.

Corsi, P. M. (1972). Human memory and the medial temporal region of the brain (Ph.D.). McGill University, Montreal.

Cowan, N. (1988). Evolving conceptions of memory storage, selective attention, and their mutual constraints within the human information-processing system. Psychological Bulletin, 104(2), 163–191.

Cowan, N. (2011). The focus of attention as observed in visual working memory tasks: making sense of competing claims. Neuropsychologia, 49(6), 1401–1406. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.01.035.

de Jong, R. (1995). Perception–action coupling and S–R compatibility. Acta Psychologica, 90(1–3), 287–299.

Desmurget, M., Prablanc, C., Arzi, M., Rossetti, Y., Paulignan, Y., & Urquizar, C. (1996). Integrated control of hand transport and orientation during prehension movements. Experimental Brain Research, 110(2), 265–278.

Deubel, H., Schneider, W. X., & Paprotta, I. (1998). Selective Dorsal and Ventral Processing: evidence for a Common Attentional Mechanism in Reaching and Perception. Visual Cognition, 5(1–2), 81–107. doi:10.1080/713756776.

Dirnberger, G., Reumann, M., Endl, W., Lindinger, G., Lang, W., & Rothwell, J. C. (2000). Dissociation of motor preparation from memory and attentional processes using movement-related cortical potentials. Experimental Brain Research, 135(2), 231–240.

Dodd, M. D., & Shumborski, S. (2009). Examining the influence of action on spatial working memory: the importance of selection. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62(6), 1236–1247.

Duncan, J. (1984). Selective attention and the organization of visual information. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 113(4), 501–517.

Essig, K., Maycock, J., Ritter, H., & Schack, T. (2011). The Cognitive Nature of Action—A Bi-Modal Approach towards the Natural Grasping of Known and Unknown Objects. IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS 2011), September 25, 63–68.

Fagioli, S., Hommel, B., & Schubotz, R. I. (2007). Intentional control of attention: action planning primes action-related stimulus dimensions. Psychological Research, 71(1), 22–29.

Fitts, P. M., & Deininger, R. L. (1954). S–R compatibility: correspondence among paired elements within stimulus and response codes. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 48(6), 483–492.

Foerster, R. M., Carbone, E., Koesling, H., & Schneider, W. X. (2011). Saccadic eye movements in a high-speed bimanual stacking task: changes of attentional control during learning and automatization. Journal of Vision, 11(7), 9. doi:10.1167/11.7.9.

Garavan, H. (1998). Serial attention within working memory. Memory & Cognition, 26(2), 263–276.

Gazzaley, A., & Nobre, A. C. (2012). Top–down modulation: bridging selective attention and working memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(2), 129–135.

Hale, S., Myerson, J., Rhee, S. H., Weiss, C. S., & Abrams, R. A. (1996). Selective interference with the maintenance of location information in working memory. Neuropsychology, 10(2), 228–240.

Hesse, C., & Franz, V. H. (2009). Memory mechanisms in grasping. Neuropsychologia, 47(6), 1532–1545.

Hollingworth, A., & Henderson, J. M. (2002). Accurate visual memory for previously attended objects in natural scenes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 28(1), 113–136. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.28.1.113.

Hommel, B. (2011). The Simon effect as tool and heuristic. Acta Psychologica, 136(2), 189–202.

Hommel, B., Müsseler, J., Aschersleben, G., & Prinz, W. (2001). The Theory of Event Coding (TEC): a framework for perception and action planning. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(5), 849–78; discussion 878-937.

Hughes, C. M. L., Seegelke, C., Spiegel, M. A., Oehmichen, C., Hammes, J., & Schack, T. (2012). Corrections in grasp posture in response to modifications of action goals. PLoS ONE, 7(9), e43015.

Ikkai, A., & Curtis, C. (2011). Common neural mechanisms supporting spatial working memory, attention and motor intention. Neuropsychologia, 49(6), 1428–1434.

Janczyk, M., & Grabowski, J. (2011). The focus of attention in working memory: evidence from a word updating task. Memory, 19(2), 211–225. doi:10.1080/09658211.2010.546803.

Jewell, G., & McCourt, M. E. (2000). Pseudoneglect: a review and meta-analysis of performance factors in line bisection tasks. Neuropsychologia, 38(1), 93–110.

Jha, A. (2002). Tracking the time-course of attentional involvement in spatial working memory: an event-related potential investigation. Brain Research, 15(1), 61–69.

Jonides, J. (1981). Voluntary versus automatic control over the mind’s eye’s movement. In J. B. Long & A. D. Baddeley (Eds.), Attention and performance: IX (pp. 187–203). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Juan, C.-H., Shorter-Jacobi, S. M., & Schall, J. D. (2004). Dissociation of spatial attention and saccade preparation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(43), 15541–15544. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403507101.

Kessels, R. P., van Zandvoort, M. J., Postma, A., Kappelle, L. J., & de Haan, E. H. (2000). The Corsi Block-Tapping Task: standardization and normative data. Applied Neuropsychology, 7(4), 252–258. doi:10.1207/S15324826AN0704_8.

Kirsch, W., & Hennighausen, E. (2010). ERP correlates of linear hand movements: distance dependent changes. Clinical Neurophysiology, 121(8), 1285–1292. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2010.02.151.

Kirsch, W., Hennighausen, E., & Rösler, F. (2009). Dissociating cognitive and motor interference effects on kinesthetic short-term memory. Psychological Research, 73(3), 380–389.

Klein, R. M. (1980). Does oculomotor readiness mediate cognitive control of visual attention? In R. S. Nickerson (Ed.), Attention and performance. VIII (pp. 259–276). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Klein, R., & Pontefract, A. (1994). Does oculomotor readiness mediate cognitive control of visual attention? Revisited! In C. Umiltà & M. Moscovitch (Eds.), Attention and performance: XV. Conscious and nonconscious information processing (pp. 333–350). Cambridge, Mass. [u.a.]: MIT Press.

Lawrence, B. M., Myerson, J., Oonk, H. M., & Abrams, R. A. (2001). The effects of eye and limb movements on working memory. Memory (Hove, England), 9(4), 433–444.

Logan, S. W., & Fischman, M. G. (2011). The relationship between end-state comfort effects and memory performance in serial and free recall. Acta Psychologica, 137(3), 292–299.

Luck, S. J., & Hillyard, S. A. (2000). The operation of selective attention at multiple stages of processing: Evidence from human and monkey electrophysiology. In M. S. Gazzaniga (Ed.), The New Cognitive Neurosciences (2nd ed., pp. 687–700). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Luck, S. J., & Vogel, E. K. (1997). The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. Nature, 390(6657), 279–281. doi:10.1038/36846.

Memelink, J., & Hommel, B. (2012). Intentional weighting: a basic principle in cognitive control. Psychological Research,. doi:10.1007/s00426-012-0435-y.

Miyake, A., & Shah, P. (Eds.). (1999). Models of Working Memory: Mechanisms of Active Maintenance and Executive Control. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Montagnini, A., & Castet, E. (2007). Spatiotemporal dynamics of visual attention during saccade preparation: Independence and coupling between attention and movement planning. Journal of Vision, 7(14), 8.1–16. doi:10.1167/7.14.8.

Murray, A. M., Nobre, A. C., & Stokes, M. G. (2011). Markers of preparatory attention predict visual short-term memory performance. Neuropsychologia, 49(6), 1458–1465.

Oberauer, K. (2003). Selective attention to elements in working memory. Experimental Psychology, 50(4), 257–269.

Ohbayashi, M., Ohki, K., & Miyashita, Y. (2003). Conversion of working memory to motor sequence in the monkey premotor cortex. Science 301(5630), 233–236.

Okon-Singer, H., Podlipsky, I., Siman-Tov, T., Ben-Simon, E., Zhdanov, A., Neufeld, M. Y., et al. (2011). Spatio-temporal indications of sub-cortical involvement in leftward bias of spatial attention. NeuroImage, 54(4), 3010–3020. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.078.

Pashler, H. (1991). Shifting visual attention and selecting motor responses: distinct attentional mechanisms. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 17(4), 1023–1040.

Paulignan, Y., Jeannerod, M., MacKenzie, C., & Marteniuk, R. (1991). Selective perturbation of visual input during prehension movements. 2. The effects of changing object size. Experimental Brain Research, 87(2), 407–420.

Posner, M. I. (1980). Orienting of attention. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32(1), 3–25.

Posner, M. I., Snyder, C. R., & Davidson, B. J. (1980). Attention and the detection of signals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 109(2), 160–174. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.109.2.160.

Postle, B. R., Awh, E., Jonides, J., Smith, E. E., & D’Esposito, M. (2004). The where and how of attention-based rehearsal in spatial working memory. Brain Research, 20(2), 194–205.

Postle, B. R., Idzikowski, C., Della Sala, S., Logie, R. H., & Baddeley, A. D. (2006). The selective disruption of spatial working memory by eye movements. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology (2006), 59(1), 100–120.

Prinzmetal, W., Presti, D. E., & Posner, M. I. (1986). Does attention affect visual feature integration? Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12(3), 361–369.

Proctor, R. W. (2011). Playing the Simon game: use of the Simon task for investigating human information processing. Acta Psychologica, 136(2), 182–188. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.06.010.

Quinn, J. G., & Ralston, G. E. (1986). Movement and attention in visual working memory. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38(4), 689–703.

Quinn, J. T., & Sherwood, D. E. (1983). Time requirements of changes in program and parameter variables in rapid ongoing movements. Journal of Motor Behavior, 15(2), 163–178.

Rizzolatti, G., & Craighero, L. (1998). Spatial attention: Mechanisms and theories. In M. Sabourin, F. Craick, & M. Robert (Eds.), Advances in psychological science. Biological and Cognitive Aspects (pp. 171–198). Montreal: Psychology Press.

Rizzolatti, G., Riggio, L., Dascola, I., & Umilta, C. (1987). Reorienting attention across the horizontal and vertical meridians: evidence in favor of a premotor theory of attention. Neuropsychologia, 25(1A), 31–40.

Rizzolatti, G., Riggio, L., & Sheliga, B. M. (1994). Space and Selective Attention. In C. Umiltà & M. Moscovitch (Eds.), Attention and performance: XV. Conscious and nonconscious information processing (pp. 231–265). Cambridge, Mass. [u.a.]: MIT Press.

Schall, J. D., & Woodman, G. F. (2012). A Stage Theory of Attention and Action. In G. R. Mangun (Ed.), The neuroscience of attention. Attentional control and selection (pp. 187–208). New York [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press.

Schiegg, A., Deubel, H., & Schneider, W. X. (2003). Attentional selection during preparation of prehension movements. Visual Cognition, 4, 409–431.

Schmidt, B., Vogel, E., Woodman, G., & Luck, S. (2002). Voluntary and automatic attentional control of visual working memory. Perception & Psychophysics, 64(5), 754–763.

Schneider, W. X. (1995). VAM: a neuro-cognitive model for visual attention control of segmentation, object recognition, and space-based motor action. Visual Cognition, 2(2–3), 331–376.

Simon, J. R. (1990). The effects of an irrelevant directional cue on human information processing. In R. W. Proctor & T. G. Reeve (Eds.), Stimulus–response compatibility. An integrated perspective (pp. 31–86). Amsterdam: North Holland.

Smith, D. T., & Schenk, T. (2012). The Premotor theory of attention: time to move on? Neuropsychologia, 50(6), 1104–1114. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.01.025.

Smith, D. T., Schenk, T., & Rorden, C. (2012). Saccade preparation is required for exogenous attention but not endogenous attention or IOR. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 38(6), 1438–1447. doi:10.1037/a0027794.

Smyth, M. M., Pearson, N. A., & Pendleton, L. R. (1988). Movement and working memory: patterns and positions in space. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 40(3), 497–514. doi:10.1080/02724988843000041.

Smyth, M. M., & Scholey, K. A. (1994). Interference in immediate spatial memory. Memory & Cognition, 22(1), 1–13.

Sperling, G. (1960). The information available in brief visual presentations. Psychological Monographs, 74, 1–29.

Spiegel, M. A., Koester, D., & Schack, T. (2013). The Functional Role of Working Memory in the (Re-)Planning and Execution of Grasping Movements. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 39(1).

Spiegel, M. A., Koester, D., Weigelt, M., & Schack, T. (2012). The costs of changing an intended action: movement planning, but not execution, interferes with verbal working memory. Neuroscience Letters, 509, 82–86. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2011.12.033.

Stelmach, G. E., Castiello, U., & Jeannerod, M. (1994). Orienting the finger opposition space during prehension movements. Journal of Motor Behavior, 26(2), 178–186.

Stoffer, T. H. (1991). Attentional focussing and spatial stimulus–response compatibility. Psychological Research, 53(2), 127–135.

Theeuwes, J., Kramer, A., & Irwin, D. (2011). Attention on our mind: the role of spatial attention in visual working memory. Acta Psychologica, 137(2), 248–251. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.06.011.

Tipper, S. P., Howard, L. A., & Houghton, G. (1998). Action-based mechanisms of attention. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 353(1373), 1385–1393. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0292.

Tipper, S. P., Lortie, C., & Baylis, G. C. (1992). Selective reaching: evidence for action-centered attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 18(4), 891–905.

Umiltà, C., & Nicoletti, R. (1992). An integrated model of the Simon effect. In J. Alegria, D. Holender, J. Junca de Morais, & M. Radeau (Eds.), Analytic approaches to human cognition (xv, pp. 331–350). Oxford: North-Holland.

van Donkelaar, P., & Franks, I. M. (1991). The effects of changing movement velocity and complexity on response preparation: evidence from latency, kinematic, and EMG measures. Experimental Brain Research, 83(3), 618–632.

Velzen, J., Gherri, E., & Eimer, M. (2006). ERP effects of movement preparation on visual processing: attention shifts to the hand, not the goal. Cognitive Processing, 7(S1), 100–101.

Vogel, E. K., Woodman, G. F., & Luck, S. J. (2001). Storage of features, conjunctions and objects in visual working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27(1), 92–114.

Weigelt, M., Rosenbaum, D. A., Huelshorst, S., & Schack, T. (2009). Moving and memorizing: motor planning modulates the recency effect in serial and free recall. Acta Psychologica, 132(1), 68–79.

Westerholz, J., Schack, T. & Koester, D. (2013). Event-related brain potentials for goal-related power grips. PLOS ONE.

Wheeler, M. E., & Treisman, A. M. (2002). Binding in short-term visual memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 131(1), 48–64.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the German Research Foundation Grant DFG EXC 277 ‘‘Cognitive Interaction Technology” (CITEC). We thank the two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on this article and Patricia Land for proofreading.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spiegel, M.A., Koester, D. & Schack, T. Movement planning and attentional control of visuospatial working memory: evidence from a grasp-to-place task. Psychological Research 78, 494–505 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-013-0499-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-013-0499-3