Abstract

Vertigo and dizziness are frequent complaints in primary care that lead to extensive health care utilization. The objective of this systematic review was to examine health care of patients with vertigo and dizziness in primary care settings. Specifically, we wanted to characterize health care utilization, therapeutic and referral behaviour and to examine the outcomes associated with this. A search of the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases was carried out in May 2015 using the search terms ‘vertigo’ or ‘dizziness’ or ‘vestibular and primary care’ to identify suitable studies. We included all studies that were published in the last 10 years in English with the primary diagnoses of vertigo, dizziness and/or vestibular disease. We excluded drug evaluation studies and reports of adverse drug reactions. Data were extracted and appraised by two independent reviewers; 16 studies with a total of 2828 patients were included. Mean age of patients ranged from 45 to 79 with five studies in older adults aged 65 or older. There were considerable variations in diagnostic criteria, referral and therapy while the included studies failed to show significant improvement of patient-reported outcomes. Studies are needed to investigate current practice of care across countries and health systems in a systematic way and to test primary care-based education and training interventions that improve outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With a high lifetime prevalence [1] and high burden of disease [2], vertigo and dizziness can be severely disabling because of its high impact on daily life [3]. Psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, panic disorders, and specific phobias such as agoraphobia or acrophobia may account for avoidance behavior, increased disability [4], and increased health care utilization [5]. Finally, vertigo and dizziness are specific and important risk factors for falls and injuries, especially in the aged [6].

Almost 45 % of outpatients with dizziness and vertigo are primarily seen and treated by a primary care physician (PCP) [7] who is often without specific neuro-otological expertise for the diagnosis and management of vestibular disorders. Management in primary care seems to be difficult because dizziness as a symptom is difficult to describe and to standardize [8]. Also, PCPs might reasonably want to exclude potentially life threatening diseases and utilize all possible diagnostic options to avoid litigation. There is evidence that PCPs are referring such “red flag” cases correctly. However, they failed to refer patients to the specialist when referral would have been appropriate [9].

Most instances of vertigo and dizziness are manageable [10–12]. Peripheral vestibular disorders are frequent causes for dizziness and vertigo; benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo (BPPV) is the most frequent form of peripheral vestibular disorders with a lifetime prevalence of 2 % in the general population [13]. Other, less-frequent peripheral forms of vestibular disorders include Menière’s disease and vestibular neuritis. Central vestibular forms of vertigo include cerebrovascular diseases, brain stem and cerebellar lesions, infections, and vestibular migraine. In aged adults, the ageing of vestibular and proprioceptive systems and, most notably, medication are potential risk factors for vertigo and dizziness.

Inappropriate management of patients with the cardinal symptoms of vertigo and dizziness may lead to chronicity, activity limitations [14] and considerable economic impact [2]. Yet studies conducted from the retrospective perspective of specialized tertiary care centers found considerable under-and misdiagnosis and irrational treatment and management practices in primary care [9, 15, 16]. Since vertigo and dizziness are frequent complaints that lead to extensive health care utilization, and since most patients are likely to rely on PCPs for the management of their complaints, it is important to know more about typical management patterns and referral practices as well as about prognosis and outcomes of dizzy patients in primary care.

Objective of this systematic review was to examine health care of patients with vertigo and dizziness in primary care settings. Specifically, we wanted to characterize health care utilization, therapeutic and referral behaviour and to examine the outcomes associated with this.

Methods

Data source

A search of the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases via OVID was carried out in May 2015 using the search terms ‘vertigo’ or ‘dizziness’ or ‘vestibular and primary care’ to identify suitable studies. Additionally, we used the sensitive/broad search filters for outcome assessment proposed by the Health Services Research Queries for MEDLINE [54]. Furthermore, we searched grey literature and checked the references of the included studies. We included all studies that were published in the last 10 years in English with the primary diagnoses of vertigo, dizziness and/or vestibular disease. We excluded drug evaluation studies and reports of adverse drug reactions. Since a pilot search revealed that the number of studies on vertigo in primary care is very limited we included all study designs and types with the exception of tutorials, case reports and case series with n < 10. Intervention studies were eligible for inclusion if there was a control arm receiving usual care, and only the results of usual care controls were reported. To ensure the quality of the search strategy, all search strategies were pilot-tested on their ability to find abstracts which were previously identified as relevant.

Data extraction and analysis

Studies were independently screened for inclusion criteria by two reviewers (EK and EG) based on title and abstract. The selected publications were subsequently reviewed based on full text. Agreement on the criteria for selecting publications had to be reached by consensus. In case of disagreement during the selection process, a third reviewer made the final decision.

We developed a data extraction sheet and pre-tested the sheet on five randomly chosen included studies. One review author extracted the data; the second author checked the extracted data.

Results

We identified 215 records through database searching. One hundred and eighty-eight records could be excluded by screening of the abstracts, leaving 27 full text articles for eligibility assessment. Eleven full texts were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria, leaving 16 publications for qualitative review. Of these 16 publications, two reported results from the same cohort study from the Netherlands [17, 18], and two reported results from the same cohort study from Germany [19, 20]. We decided to include all four publications into the qualitative review because they reported different aspects; two gave results of the baseline survey [18, 19], two gave results of the follow-up [17, 20]. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram for inclusion. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies.

Because of the heterogeneity of the included studies we did not appraise their quality systematically.

Methods

Six of the studies finally selected were cohort studies including one randomized controlled trial and one controlled trial. Eight studies were cross-sectional studies with two reporting baseline results from cohorts as mentioned above. Two studies were analyses of medical claims data or registries. Follow-up in cohort studies ranged between 6 and 12 months. One study reported data from two follow-up examinations [20]; all other cohort studies had one follow-up.

Participants

A total of 2828 patients were included in all individual studies, not counting cases from country-wide registries. Of those from individual studies, 2433 were of cross-sectional studies, 707 of cohort studies. 139 patients were controls from controlled trials. Mean age of patients ranged from 45 to 79 with 5 studies in older adults aged 65 or older and 9 studies without clear age restrictions with the age of included participants ranging from 10 to 95. Percentage of female patients ranged from 46 to 74 % with one outlier from a veterans’ primary care center (11 % women). Study populations were from Europe or from the US. Diagnoses were mostly unspecific dizziness and vertigo with few studies reporting clear diagnostic criteria for e.g. benign paroxysmal positional vertigo or peripheral vestibular disease. Table 2 provides the diagnostic criteria mentioned in the included studies.

Results of individual studies

Consultations, referrals and therapy

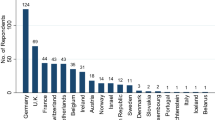

Ten studies reported data on health care utilization and consultation and referral patterns [2, 20–28]. Lin et al. estimated a total of 1.49 Mio consultations for otologic diagnoses per year for the US population aged 65 and older (own calculations), with a rate of 6 consultations per 1000 aged inhabitants per year for BPPV, 8 per 1000 for Menière’s Disease and 7 per 1000 for vestibular neuritis [24]. For the total population in Spain Garrigues reported that 17.8 individuals per 1000 inhabitants per year had at least one consultation for vertigo, 7.6 per 1000 for acute incident vertigo [21]. Seventeen percent of all adults in Germany had had at least one medical consultation in life for dizziness or vertigo [2]. Of patients with dizziness and vertigo, 60 to 80 % contacted the PCP for treatment in UK [25, 28], in Germany 58 % had at least one medical consultation, also predominantly in primary care, [2]. Likewise, in the US 55 % of patients with dizziness were initially seen by the PCP [26]. Depending on health system and availability physicians from other medical specialities were also consulted with PCPs, neurologists, otorhinolaryngologists and orthopaedists being the most frequently mentioned. Previous hospitalization was reported by 2 % of all German adults [2].

Despite unresolved diagnosis, only 22 % of the patients seen by a PCP in the US veterans’ health service were referred to specialists [26]. In contrast, German PCPs referred 48 % of their dizzy patients to at least one specialist. In 18 % of the cases the specialist’s diagnosis differed from the PCP’s [20]. Also, 46 % of the patients with a confirmed diagnosis of psychosomatic vertigo were nevertheless referred to specialists for further clinical examination and therapy [27]. Two percent of patients initially seen by a German PCP were sent to hospital [20]. Individuals with chronic dizziness rated the physician’s empathy concerning their complaints significantly lower than individuals with acute incident dizziness [20]. For patients with BPPV, median waiting time between referral and effective management was 22 to 27 weeks in the UK [23].

Of those patients seen by a PCP in the UK, 90 % received medication, 40 % physiotherapy, 10 % psychotherapy [25]. Likewise, 58 % of patients with confirmed vestibular causes of dizziness received medication [28]. Even though having received a recommendation, 20 % of the patients with psychosomatic vertigo did not receive psychotherapy, and 20 % received less than 12 sessions of outpatient psychotherapy [27].

Outcomes and prognosis

As shown in Table 3, only seven studies examined patient-reported outcomes, five of them longitudinally. Most frequently reported outcome was dizziness-specific functioning as operationalized by the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) [29] or the Vestibular Handicap Questionnaire (VHQ) [17–20, 22, 27, 28, 30]. Four studies examined generic health-related quality of life using four different measures [2, 19, 20, 27, 28]. Two studies reported vertigo-related symptoms using the Vertigo Symptom Scale (VSS) [27, 28]. One study examined the rates of adults with vertigo obtaining disability pension [31]. Generic activities of daily living were examined in one study [19, 20]. One study reported costs and cost per quality adjusted life years [28]. There were no statistically significant or clinically relevant changes in specific functioning during follow-up time. Mean score of the DHI of the included patients was mostly above the threshold of 26 indicating moderate to severe impairment. Score changes failed to reach the minimal clinically relevant difference of 12 [32]. Physical quality of life and vertigo-related symptoms improved significantly in one study in patients with confirmed psychogenic vertigo [27].

Discussion

This systematic review of the recent literature suggests that health care of patients with vertigo and dizziness in primary care settings is still suboptimal. The examined studies failed to show significant improvement of patient-reported outcomes while there were considerable variations in referral and therapy.

Our review suggests that there is a scarcity of studies, specifically of longitudinal studies investigating the processes and outcomes of usual care of vertigo and dizziness in primary care, and of controlled trials testing the implementation of improved care options. The included studies confirm that, regardless of country and health system, about 2 % of the adult population per year sees a physician because of vertigo; among those consultations, PCPs are seen predominantly. These findings from the last 10 years compare well with an earlier study that reported that nearly 45 % of dizzy outpatients are first seen by the general practitioner, and that vertigo and dizziness constitute frequent reasons to see the PCP [7].

Regarding diagnostic criteria, the studies examined here present a large variety of definitions for vertigo and dizziness including the rather superficial coding as it is found in medical claims data. This matches the observation that unclear dizziness often remains the main primary diagnosis and is not further classified into the more specific categories of central or peripheral origin. Especially, BPPV, multisensory dizziness, and vestibular migraine are under-diagnosed by referring physicians [15]. It is noteworthy that diagnostic work-up might be difficult even for specialists due to somehow vague diagnostic criteria and their repetitive change. In a study comparing physicians’ decision making for dizzy patients in an ENT clinic to a neurotologic expert system, the specialists were able to solve 69 % of the cases while the expert system solved 65 % [33]. Ultimately, incomplete diagnostic work-up will lead to unsuccessful therapy attempts and eventually to chronification.

In a recent study from the US, dizziness and vertigo were among the most frequently referred neurological symptoms [34]. There are several possible reasons why the speciality referral rate by PCPs exceeded this 14 % referral rate for neurological symptoms. Vertigo and dizziness are potentially difficult to diagnose for the PCP, thus the amount of complexity of diagnosis and therapy may be one primary reason for referral. With the exception of BPPV, verification of a causative lesion needs sophisticated testing, and the PCP might want to exclude potential life-threatening diseases, e.g. by imaging. Nevertheless, in the majority of cases diagnostic imaging procedures such as magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck fail to identify the cause of dizziness [35]. Another reason for frequent referral might be that PCPs’ workload precludes detailed investigations. This does not, however, explain why patients with established psychosomatic vertigo are referred for further diagnostic procedures, or why the appropriate treatment, in this case, psychotherapy, is withheld. A recent review of the literature showed that, despite large variation, PCPs’ referral rates do not always reflect optimal care decisions [36]. One major drawback of referral is the potentially long waiting time until appointment with the specialist as reported by a study from the UK [23]. Many instances of peripheral disease might resolve spontaneously within that time or fluctuate. This can affect interpretation of the preliminary findings but also speed chronification and the development of secondary psychosomatic disease.

Regarding treatment, the high percentage of patients receiving medication merits mentioning. Although the use of vestibular suppressants can be indicated in an acute stage of disease, they may inhibit vestibular compensation and are therefore largely inappropriate, e.g. in BPPV [13]. Other therapies with known efficacy were hardly reported; namely vestibular rehabilitation and involvement of physical therapists were underrepresented.

In line with earlier work there was a multitude of different and hardly comparable outcome measures from the domains of functioning, quality of life and symptom severity [37–39]. It is interesting to note that none of the studies investigating mid- and long-term outcomes under usual care conditions could show significant or clinically relevant improvement in functioning. For the dizzy patient, this prospect is hardly satisfying because many causes of vertigo and dizziness are manageable in theory, and have a benign prognosis. To give an example, in a recent observational study with 2 years’ follow-up, patients diagnosed and treated in a specialized tertiary care clinic improved significantly with a mean reduction of the DHI score of 14 points [40]. Favorable change could be observed for all disease entities, but the difference was largest for patients with BPPV. Specifically because BPPV is well-treatable [41] it should primarily be managed in primary care.

We are aware that this systematic review of the literature has several limitations. Although a formal quality appraisal was hardly feasible because of study heterogeneity we noted considerable discrepancies in the included studies regarding methodological rigorousness. In general, sample sizes were small resulting in high variance of the reported prevalences and effect estimates. The small sample size may be partly explained by the recruiting process. The ability of including a representative sample of patients through their PCP will vary depending on the country-specific health system. Research will be easy in countries with a well-developed PCP system with formalized referrals where the PCP acts as a gate-keeper for other specialities, and it may be less straightforward in health systems where community-based specialists compete with PCPs as primary access point for patients [42]. The same applies for varying referral rates. The low number of high-quality studies is surprising but underlines the low awareness of vertigo and dizziness as health problems that are relevant not only to the specialist but rather to daily routine of the PCP [2].

In conclusion, diagnosis and management of vertigo and dizziness needs to be streamlined for primary care. Practical algorithms should be developed and implemented that take into account time and resource restrictions of PCPs, but give pragmatic instructions how to proceed with dizzy patients and to make correct referral and treatment decisions so that those with manageable disease will receive timely treatment, and those who are in risk for serious illness or benefit from specialist consultation will be forwarded to tertiary care. Close cooperation with specialists and other health professions should be part of the routine. Studies are needed to investigate current practice of care across countries and health systems in a systematic way and to test PCP-based education and training interventions that improve patient-reported outcomes.

References

Neuhauser HK, von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, Feldmann M, Ziese T, Lempert T (2005) Epidemiology of vestibular vertigo: a neurotologic survey of the general population. Neurology 65(6):898–904

Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern M, Lezius F, Feldmann M, Lempert T (2008) Burden of dizziness and vertigo in the community. Arch Intern Med 168(19):2118–2124

Mueller M, Schuster E, Strobl R, Grill E (2012) Identification of aspects of functioning, disability and health relevant to patients experiencing vertigo: a qualitative study using the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Health Qual Life Outcomes 10:75

Yardley L, Owen N, Nazareth I, Luxon L (1998) Prevalence and presentation of dizziness in a general practice community sample of working age people. Br J Gen Pract 48(429):1131–1135

Wiltink J, Tschan R, Michal M, Subic-Wrana C, Eckhardt-Henn A, Dieterich M, Beutel ME (2009) Dizziness: anxiety, health care utilization and health behavior–results from a representative German community survey. J Psychosom Res 66(5):417–424

Gazzola JM, Gananca FF, Aratani MC, Perracini MR, Gananca MM (2006) Circumstances and consequences of falls in elderly people with vestibular disorder. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 72(3):388–392

Sloane PD (1989) Dizziness in primary care. Results from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Fam Pract 29(1):33–38

Newman-Toker DE, Cannon LM, Stofferahn ME, Rothman RE, Hsieh YH, Zee DS (2007) Imprecision in patient reports of dizziness symptom quality: a cross-sectional study conducted in an acute care setting. Mayo Clin Proc 82(11):1329–1340

Bird JC, Beynon GJ, Prevost AT, Baguley DM (1998) An analysis of referral patterns for dizziness in the primary care setting. Br J Gen Pract 48(437):1828–1832

Lopez-Escamez JA, Gamiz MJ, Fernandez-Perez A, Gomez-Finana M (2005) Long-term outcome and health-related quality of life in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 262(6):507–511

Mendel B, Bergenius J, Langius-Eklof A (2010) Dizziness: a common, troublesome symptom but often treatable. J Vestib Res 20(5):391–398

Strupp M, Brandt T (2009) Current treatment of vestibular, ocular motor disorders and nystagmus. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2(4):223–239

von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, Feldmann M, Ziese T, Lempert T, Neuhauser H (2007) Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78(7):710–715

Mueller M, Strobl R, Jahn K, Linkohr B, Peters A, Grill E (2014) Burden of disability attributable to vertigo and dizziness in the aged: results from the KORA-Age study. Eur J Public Health 24(5):802–807

Geser R, Straumann D (2012) Referral and final diagnoses of patients assessed in an academic vertigo center. Front Neurol 3:169

Grill E, Strupp M, Muller M, Jahn K (2014) Health services utilization of patients with vertigo in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. J Neurol 261(8):1492–1498

Dros J, Maarsingh OR, Beem L, van der Horst HE, ter Riet G, Schellevis FG, van Weert HC (2012) Functional prognosis of dizziness in older adults in primary care: a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc 60(12):2263–2269

Maarsingh OR, Dros J, Schellevis FG, van Weert HC, van der Windt DA, ter Riet G, van der Horst HE (2010) Causes of persistent dizziness in elderly patients in primary care. Ann Fam Med 8(3):196–205

Kruschinski C, Sczepanek J, Wiese B, Breull A, Junius-Walker U, Hummers-Pradier E (2011) A three-group comparison of acute-onset dizzy, long-term dizzy and non-dizzy older patients in primary care. Aging Clin Exp Res 23(4):288–295

Sczepanek J, Wiese B, Hummers-Pradier E, Kruschinski C (2011) Newly diagnosed incident dizziness of older patients: a follow-up study in primary care. BMC Fam Pract 12:58

Garrigues HP, Andres C, Arbaizar A, Cerdan C, Meneu V, Oltra JA, Santonja J, Perez A (2008) Epidemiological aspects of vertigo in the general population of the Autonomic Region of Valencia. Spain. Acta Otolaryngol 128(1):43–47

Hansson EE, Mansson NO, Hakansson A (2005) Balance performance and self-perceived handicap among dizzy patients in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care 23(4):215–220

Leong AC, Barker F, Bleach NR (2008) Primary assessment of the vertiginous patient at a pre-ENT balance clinic. J Laryngol Otol 122(2):132–138

Lin HW, Bhattacharyya N (2011) Otologic diagnoses in the elderly: current utilization and predicted workload increase. Laryngoscope 121(7):1504–1507

Nazareth I, Landau S, Yardley L, Luxon L (2006) Patterns of presentations of dizziness in primary care—a cross-sectional cluster analysis study. J Psychosom Res 60(4):395–401

Polensek SH, Sterk CE, Tusa RJ (2008) Screening for vestibular disorders: a study of clinicians’ compliance with recommended practices. Med Sci Monit 14(5):CR238–CR242

Tschan R, Best C, Wiltink J, Beutel ME, Dieterich M, Eckhardt-Henn A (2013) Persistence of symptoms in primary somatoform vertigo and dizziness: a disorder “lost” in health care? J Nerv Ment Dis 201(4):328–333

Yardley L, Barker F, Muller I, Turner D, Kirby S, Mullee M, Morris A, Little P (2012) Clinical and cost effectiveness of booklet based vestibular rehabilitation for chronic dizziness in primary care: single blind, parallel group, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 344:e2237

Jacobson GP, Newman CW (1990) The development of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 116(4):424–427

Hansson EE, Mansson NO, Ringsberg KA, Hakansson A (2008) Falls among dizzy patients in primary healthcare: an intervention study with control group. Int J Rehabil Res 31(1):51–57

Skoien AK, Wilhemsen K, Gjesdal S (2008) Occupational disability caused by dizziness and vertigo: a register-based prospective study. Br J Gen Pract 58(554):619–623

Tamber AL, Wilhelmsen KT, Strand LI (2009) Measurement properties of the Dizziness Handicap Inventory by cross-sectional and longitudinal designs. Health Qual Life Outcomes 7:101

Kentala E, Auramo Y, Juhola M, Pyykko I (1998) Comparison between diagnoses of human experts and a neurotologic expert system. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 107(2):135–140

Barnett ML, Song Z, Landon BE (2012) Trends in physician referrals in the United States, 1999–2009. Arch Intern Med 172(2):163–170

Colledge NR, Barr-Hamilton RM, Lewis SJ, Sellar RJ, Wilson JA (1996) Evaluation of investigations to diagnose the cause of dizziness in elderly people: a community based controlled study. BMJ 313(7060):788–792

Mehrotra A, Forrest CB, Lin CY (2011) Dropping the baton: specialty referrals in the United States. Milbank Q 89(1):39–68

Alghwiri AA, Marchetti GF, Whitney SL (2011) Content comparison of self-report measures used in vestibular rehabilitation based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Phys Ther 91(3):346–357

Duracinsky M, Mosnier I, Bouccara D, Sterkers O, Chassany O, Working Group of the Societe Francaise dO-R-L (2007) Literature review of questionnaires assessing vertigo and dizziness, and their impact on patients’ quality of life. Value Health 10(4):273–284

Grill E, Bronstein A, Furman J, Zee DS, Muller M (2012) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Core Set for patients with vertigo, dizziness and balance disorders. J Vestib Res 22(5–6):261–271

Obermann M, Bock E, Sabev N, Lehmann N, Weber R, Gerwig M, Frings M, Arweiler-Harbeck D, Lang S, Diener HC (2015) Long-term outcome of vertigo and dizziness associated disorders following treatment in specialized tertiary care: the Dizziness and Vertigo Registry (DiVeR) Study. J Neurol 262:2083–2091

Sekine K, Imai T, Sato G, Ito M, Takeda N (2006) Natural history of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and efficacy of Epley and Lempert maneuvers. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 135(4):529–533

Hummers-Pradier E, Beyer M, Chevallier P, Eilat-Tsanani S, Lionis C, Peremans L, Petek D, Rurik I, Soler JK, Stoffers HE, Topsever P, Ungan M, Van Royen P (2009) The research agenda for general practice/family medicine and primary health care in Europe. Part 1. Background and methodology. Eur J Gen Pract 15(4):243–250

Ekvall Hansson E, Mansson NO, Hakansson A (2005) Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo among elderly patients in primary health care. Gerontology 51(6):386–389

Yardley L, Kirby S, Barker F, Little P, Raftery J, King D, Morris A, Mullee M (2009) An evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of booklet-based self-management of dizziness in primary care, with and without expert telephone support. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord 9:13

Tschan R, Wiltink J, Best C, Beutel M, Dieterich M, Eckhardt-Henn A (2010) Validation of the German version of the Vertigo Handicap Questionnaire (VHQ) in patients with vestibular vertigo syndromes or somatoform vertigo and dizziness. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 60(9–10):e1–12

Bullinger M, Kirchberger I (1998) Der SF-36 Fragebogen zum Gesundheitszustand: Handbuch fuer die deutschsprachige Fragebogenversion. Hogrefe, Goettingen

Turner-Bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M (2003) Usefulness of the SF-8 Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Qual Life Res 12(8):1003–1012

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34(3):220–233

EuroQol G (1990) EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 16(3):199–208

Yardley L, Masson E, Verschuur C, Haacke N, Luxon L (1992) Symptoms, anxiety and handicap in dizzy patients: development of the vertigo symptom scale. J Psychosom Res 36(8):731–741

Shiek J, Yesavage J (1986) Geriatric Depression Scale; recent findings and development of a short version. Howarth Press, New York

Franke G (1995) SCL-90-R: Die Symptom-Checkliste von Derogatis. Deutsche Version-Manual. Beltz, Goettingen

Fillenbaum GG (1985) Screening the elderly. A brief instrumental activities of daily living measure. J Am Geriatr Soc 33(10):698–706

Wilczynski NL (2004) Optimal search strategies for detecting health services research studies in MEDLINE. CMAJ 171(10):1179–1185

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by funds from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research under the Grant Code 01EO1401. The authors bear full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This manuscript is part of a supplement sponsored by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research within the funding initiative for integrated research and treatment centers.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Grill, E., Penger, M. & Kentala, E. Health care utilization, prognosis and outcomes of vestibular disease in primary care settings: systematic review. J Neurol 263 (Suppl 1), 36–44 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-015-7913-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-015-7913-2