Abstract

Introduction

To study the association between potential prognostic factors and functional outcome at 1 and 5 year follow-up in patients with femoral neck fractures treated with an arthroplasty. To analyze the reliability of the Harris hip score (HHS).

Materials and methods

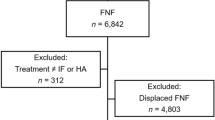

A multicenter analysis which included 252 patients who sustained a femoral neck fracture treated with an arthroplasty. Functional outcome after surgery was assessed using a modified HHS and was evaluated after 1 (HHS1) and 5 (HHS5) years. Several prognostic factors were analyzed and reliability of the HHS was assessed.

Results

After 1 year the presence of co-morbidities was a significant (p = 0.002) predictor for a poor functional outcome (mean HHS1 71.8 with co-morbidities, and 80.6 without co-morbidities). After 5 years none of the potential prognostic factors had significant influence on functional outcome. Internal consistency testing of the HHS showed that when pain and function of the HHS were analyzed together, the internal consistency was poor (HHS1 0.38 and HHS5 0.20). The internal consistency of the HHS solely in function (without pain) improved to 0.68 (HHS1) and 0.46 (HHS5). Analyzing the functional aspect exclusively, age and the existence of co-morbidities could be defined as predictors for functional outcome of femoral neck fractures after 1 and 5 years.

Conclusion

After using the HHS in a modification, age and the existence of pre-operative co-morbidities appeared to be predictors of the functional outcome after 1 and 5 years. The HHS, omitting pain, is a more reliable score to estimate the functional outcome, than HHS analyzing pain and function in one scoring system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Complex combinations of static and dynamic stresses are responsible for hip pain in patients without osteoarthritis [1, 2]. Fractures of the femoral neck are common fractures and an important cause of hip pain, especially in elderly people. Approximately, one-third of the elderly population sustain a fall each year, and about 1% of these falls result in a hip fracture [3, 4]. Falls are associated with significant morbidity estimated around 50% and a mortality ranging from 11 to 20% [5, 6] a decreased level of independence, and admission to a nursing home [3, 7–9]. In the Netherlands, 17,000 patients suffer from a hip fracture each year (Dutch National Public Health Compass, http://www.nationaalkompas.nl). The overall increase in hip fracture rates can be explained in part by the increase in the number of very old patients (>85 years). Consequently, the number of hip fractures is expected to rise substantially in the coming decades [3, 10, 11]. Hip fractures thus are becoming a major public health problem [4, 10]. Despite the frequency of this fracture and the serious consequences associated with it, little is known about the progress and pattern of functional changes that can be expected during rehabilitation [3].

Various studies concerning functional outcome of operative treatment of hip fractures have been performed [7, 9, 12–19] most of them with less than 5 years follow-up. Several studies identified predictors of this functional outcome [16, 19–24]. For an elderly patient with a femoral neck fracture, the ability to mobilize in their own home, and their community, would determine their ability to live independently [24]. Before surgical treatment of a femoral neck fracture, the patients and their relatives have to be informed of what they have to expect concerning the effect of pre-and peri-operative risk factors on the outcome of surgery, post-operative rehabilitation, daily care and other social issues. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify prognostic factors for functional outcome, using the Harris hip score (HHS), after a femoral neck fracture treated with an arthroplasty at 1-year and 5-year follow-up.

Patients and methods

Study population

For the purpose of this study, we used data collected for the prospective randomized controlled trial: hemiarthroplasty (HA) versus total hip replacement (THR) outcome [25] for which approval from the Medical Ethics Committee was obtained. This study included 252 patients with a femoral neck fracture in one academic and seven district hospitals, between January 1995 and January 2002. The last follow-up was in January 2007. Follow-up of the patients was performed at 1 and 5 years post-operatively. In this database the demographics, pre-, peri- and post-operative data, and functional scores of all patients were registered. Exclusion criteria were: (a) rheumatoid arthritis, (b) pathological fractures, (c) pre-operative immobility, (d) senile dementia, and (e) patients not able or willing to give their informed consent. Their baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Surgical intervention

The general intention was to operate as soon as possible. Surgery would preferably take place within 24 h after the trauma [26, 27] unless the procedure could not be performed due to medical contra-indications or logistic reasons (e.g., intervention during the night). All patients received 2 g of Rocephin i.v. as prophylactic antibiotics, 30 min before the incision. The operation was performed by (or under supervision of) an orthopedic or trauma surgeon. It was left to the expertise of the surgeon which approach (anterolateral, lateral or posterolateral) was taken. Two different implants were used: a cemented “Weber Rotationsprothese” or a cemented “Müller Geradschaftprothese”, both in the HA- and THR-modification. The application of a wound drain was left to the discretion of the surgeon. The rehabilitation protocol was standardized for all patients, and consisted of full weight bearing from the first post-operative day.

Primary assessment and follow-up

The primary assessment established that the patients fulfilled the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Applicable case report forms had been completed upon admission. This form required information about pre-operative morbidity, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification and functional activity before the fracture. The case report forms, filled in after the operation and upon discharge, contained information about the surgical treatment (HA or THR), surgeon, blood loss, peri-and post-operative in-hospital local and general complications, and length of admission stay. The patient’s follow-up contacts were scheduled at 1 and 5 years after the operation. All the pre-, peri- and post-operative forms were collected, checked and if necessary corrected by one researcher (ER). During these visits local and general complications were registered, as well as the functional status, expressed in a modified HHS [25]. This modification is the HHS without the physical examination section, is based on an assessment of pain and function of the patient, and has been used in earlier studies [28, 29]. This study did not use the physical examination part because on one hand this information was hard to assemble in the follow-up of 5 years due to this old population group. For example it was a problem for them to come to the outpatient department. On the other hand, the physical examination section implies only five points in the total HHS of 100 points. To acquire a maximum score of 100, the score was converted with a correction factor and ranged from 0 to 100, in which 0 implies poor and 100 excellent function.

Prognostic factors

As potential prognostic factors for functional outcome were considered age, pre-operative co-morbidity, ASA-classification, type of arthroplasty (HA or THR), surgeon (resident or consultant), interval between trauma and operation, blood loss, peri-and post-operative in-hospital complications and general post-operative in-hospital complications (Tables 1 and 2). In-hospital complications were defined as adverse medical situations that lead to a change in treatment. Pre-operative co-morbidity was divided into six categories: (a) cardiovascular, (b) respiratory, (c) neurological, (d) musculoskeletal, (e) malignancies, and (f) endocrine. In order to quantify health problems pre-operatively, the ASA classification system was used. The categories were defined as follows: ASA 1 normal healthy patient, ASA 2 patient with mild systemic diseases, ASA 3 patient with severe systemic diseases, ASA 4 patient with severe incapacitating systemic condition, constant threat to life, and ASA 5 moribund patient. To identify the functional outcome of the patient after surgery, the HHS [30] was modified as described by Van den Bekerom [25].

Statistics

Two investigators (ER, MB) entered all data in SPSS database which was checked for accuracy by another investigator (IS, EH). All calculations and statistical analyses of the complete database were also performed with use of SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as proportions and continuous variables as means and standard deviations. To identify those factors associated with functional outcome, we performed a multivariable linear regression analysis. Therefore, we first assessed the association between independent factors (age, pre-operative co-morbidity, ASA-score, type of arthroplasty (HA or THR), surgeon, interval between trauma and operation, blood loss, local peri-and post-operative in-hospital complications associated with the arthroplasty and general post-operative in-hospital complications), and dependent factors (HHS at 1 and 5 years post operatively) by use of univariate analyses. The variables significantly associated in the univariate analyses were entered into a multivariable linear regression analysis. A P value of <0.05 indicated statistical significance. In addition, internal consistency of the HHS was assessed by calculation of Cronbach’s alpha as a measure of reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha describes how well a set of variables measures a single unidimensional latent construct. Values ≥0.7 are regarded as satisfactory [31–33].

Results

Results concerning the interval between trauma and operation, type of surgeon, type of implant, blood loss and length of hospital stay are listed in Table 2. In nine (3.6%) patients there were peri-operative complications related to the arthroplasty. Thirty-two (13%) local post-operative in-hospital complications associated with the arthroplasty were registered. In addition, 81 (32.2%) general post-operative in-hospital complications were documented. All local and general complications are listed in Table 2.

Functional outcome

The follow-up percentages of patients who were eligible to complete the HHS after 1 and 5 years were, respectively, 148 out of 217 patients (68.2%) and 120 out of 123 patients (97.2%). Thirty-four patients (14%) died in the first post-operative year. After 5 years the mortality was 48%. Multivariable analysis of the independent factors showed no significant association on the functional outcome among most of the potential prognostic factors (age, ASA-classification, type of arthroplasty, surgeon, interval between trauma and operation, blood loss, intra- and post-operative in-hospital complications related to the arthroplasty and general post-operative in-hospital complications), as illustrated in Table 3. However, the existence of pre-operative co-morbidities had a significant influence on the functional outcome after 1 year (p = 0.002). The mean HHS after 1 year (HHS1) without the existence of co-morbidities was 80.6 (SD 15.7). When a patient had one or more co-morbidities, the mean HHS1 was 71.8 (SD 14.6). After 5 years this factor had no influence on the HHS (Fig. 1).

Functional outcome; mean (SD) modified Harris hip scores with and without co-morbidities after 1 (HHS1) and 5 (HHS5) year post-operative. HHS1 without co-morbidities: 80.6 (15.7), HHS1 with co-morbidities: 71.8 (14.6). HHS5 without co-morbidities: 73.1 (17.4), HHS5 with co-morbidities: 73.2 (13.4). * p = <0.01

Reliability

This study calculated the reliability of the HHS with and without the pain score. The reliability of the HHS1 and HHS5 was very low when pain and function of the HHS were analyzed together (HHS1 0.38 and HHS5 0.20). When only the function domain was analyzed (without the pain domain), the Cronbach’s alpha of the HHS1 and HHS5 improved to 0.68 and 0.46, respectively. Based on these results, we divided the HHS into a pain and a function domain and evaluated the significance of the potential prognostic factors on both domains of the HHS separately (Table 3). For the HHS1 on pain, no significant prognostic factors could be identified. For the HHS5 on pain, age and the existence of co-morbidities were significant predictive factors in the multivariate analyses (p = 0.03 and p = 0.04, respectively). The statistical analysis of the function domain of the HHS showed that the multivariate analyses for age (HHS1: p < 0.01 and HHS5: p < 0.01) and the existence of co-morbidities (HHS1: p < 0.01 and HHS5: p < 0.01) were significant after 1 and 5 years.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify prognostic factors for functional outcome after a femoral neck fracture treated with an arthroplasty at 1-year and 5-year follow-up. The use of the modified HHS for functional outcome in this study was questioned since the reliability analyses showed that the entire HHS did not cover the same construct. Apparently, when omitting pain, the reliability of the HHS increased, but was still not sufficient (≥0.7) [32]. Therefore, we selectively evaluated the function and pain domain separately. Our study showed that both age (>80 years) and the existence of co-morbidities were predictive for functional outcome after 1 and 5 years, concerning only the function domain of the HHS.

These results are confirmed by several other studies that showed that age and co-morbidities can contribute to functional outcome. Age is a reliable predictor of functional result after a hip fracture [10, 12, 16, 34]. Michel et al. [16] also showed that patients with a mean age of ≤80 yield a better functional status 1 year after surgical intervention than older patients. However, they also described that these younger patients showed a better pre-operative functional status and less co-morbidity than patients older than 80 years, which could explain their good functional results. Nilsdotter [35] concluded that younger patients (≤72 years) gained more function 1 year after a THR than older patients, except for pain. Several other studies described that the existence of pre-operative co-morbidity might contribute to functional short- and long-term outcomes [15]. Koval and Zuckerman [10] and Magaziner [34] showed that the presence of one or more co-morbidities was a predictor of failure to recover pre-fracture basic activities. A study by Davis et al. [36] concerning predictors of functional outcome after hip arthroplasty also showed that the fewer the co-morbidities the better the outcomes following a revision of a total hip arthroplasty would be.

In contrast to the 1-year results, the entire HHS in our study could not distinguish between functional results of patients with and without co-morbidities at 5 years post-operatively. This finding was surprising, because one would expect that the influence of co-morbidities would increase after 5 years rather than decreasing. However, it might be possible that bias of the population group influenced the HHS after 5 years, because the frailest patients had died and healthy patients survived. When we assessed the internal consistency of the entire HHS, reliability was very poor (0.38 after 1 year and 0.20 after 5 years). However, when the reliability was tested with the function aspect separately, Cronbach’s alpha increased (0.68 after 1 year and 0.46 after 5 years). However, the reliability was still moderate, in comparison to the hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS), The HOOS is a questionnaire which evaluates functional problems and symptoms associated with hip disabilities. Recent studies show a much higher internal consistency of this scoring system, ranging from 0.66 to 0.96 between different subscales [37–40].

Despite the fact that this study discovered a poor reliability of the HHS, it is still one of the most widely used rating system for the disabled hip [41]. Nevertheless, only a few minor validity tests, all about the construction of the HHS [41–43], and two reliability tests have been presented for this scoring system [41]. Bryant et al. [42] compared different scoring methods and finally suggested that only three variables, walking distance, hip flexion and pain, should be assessed to measure the outcomes of hip arthroplasty. Soderman and Malchau [41] compared the HHS with other rating scales and indicated high validity and reliability for the HHS. However, the pain section of the HHS comprises almost half of the total score. This could mean that after a supposed pain free hip replacement but impaired post-operative hip function, patients could still obtain a reasonable HHS.

One of the strengths of our study is that the functional status of our patients with an arthroplasty due to a femoral neck fracture was evaluated up until 5 years after the surgery. Secondly, the data we used were derived from a prospective randomized study undertaken by Van den Bekerom et al. [25]. This study covered an extended period of time, and our study group consisted of very old people, who were difficult to involve in a long running investigation. A substantial number of patients moved from their homes to nursing homes or hospitals. In spite of this, we were able to achieve a high percentage of follow-up. Additionally, the low number of missing in this patient group during the 5 years is a major strength of this study, compensating for the relatively small number of patients included (n = 252), which could be considered a limitation of this study. Several studies that also investigated functional outcome in hip fractures, included more patients, but followed them for only 3–12 months [7–9, 15, 44].

Since the patient population of the randomized control trial from Van Bekerom et al. [25] was selected by strict inclusion- and exclusion criteria, care should be taken in the interpretation of the results of this study. Patients suffering from, for example, senile dementia or rheumatoid arthritis were excluded and could cause an overestimation of the functional score. Therefore, the results should not be generalized. Furthermore, there is a disproportion of this study population with any co-morbidity (32%) and ASA 1 classification (12%). This could be explained by additional contributing health factors such as smoking habits of the patient, age and obesity. Another explanation might be that, the consistency of the ASA definition has been discussed in other studies before. It has been described that anesthetists give different versions of the ASA definition, because the classification is indefinite and far from perfect [45, 46].

Studies using the HHS as a rating system should be aware of the inconsistency it might introduce in measuring the functional result. Using the HHS solely with the function domain, might give a more reliable functional outcome after hip replacement in the elderly. Future studies might consider using the HOOS questionnaire to evaluate symptoms and functional problems associated with the hip. Further research on functional outcomes after femoral neck fractures and the reliability of the HHS are needed.

Conclusion

-

1.

When function of the HHS is analyzed separately, age and the existence of pre-operative co-morbidities are predictors of the functional outcome after 1 and 5 years post-operatively.

-

2.

The value of the Harris hip score is limited in measuring the functional result in elderly patients with a femoral neck fracture treated with an arthroplasty. The HHS, omitting pain, is a more reliable score to estimate the functional outcome.

References

Bedi A, Dolan M, Leunig M et al (2011) Static and dynamic mechanical causes of hip pain. Arthroscopy 27:235–251

Bowman KF Jr, Fox J, Sekiya JK (2010) A clinically relevant review of hip biomechanics. Arthroscopy 26:1118–1129

Cumming RG, Nevitt MC, Cummings SR (1997) Epidemiology of hip fractures. Epidemiol Rev 19:244–257

Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF (1988) Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med 319:1701–1707

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2004) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence, mortality and disability associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:897–902

Leibson CL, Tosteson AN, Gabriel SE et al (2002) Mortality, disability, and nursing home use for persons with and without hip fracture: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc 50:1644–1650

Hannan EL, Magaziner J, Wang JJ et al (2001) Mortality and locomotion 6 months after hospitalization for hip fracture: risk factors and risk-adjusted hospital outcomes. JAMA. 285:2736–2742

Orosz GM, Magaziner J, Hannan EL et al (2004) Association of timing of surgery for hip fracture and patient outcomes. JAMA. 291:1738–1743

Wolinsky FD, Fitzgerald JF, Stump TE (1997) The effect of hip fracture on mortality, hospitalization, and functional status: a prospective study. Am J Public Health 87:398–403

Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD (1998) Hip fractures are an increasingly important public health problem. Clin Orthop Relat Res 348:2

Rockwood PR, Horne JG, Cryer C (1990) Hip fractures: a future epidemic? J Orthop Trauma 4:388–393

Cornwall R, Gilbert MS, Koval KJ et al (2004) Functional outcomes and mortality vary among different types of hip fractures: a function of patient characteristics. Clin Orthop Relat Res 425:64–71

Di MM, Vallero F, Di MR et al (2004) Functional recovery and length of stay after hip fracture in patients taking corticosteroids. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 83:633–639

Ishida Y, Kawai S, Taguchi T (2005) Factors affecting ambulatory status and survival of patients 90 years and older with hip fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 436:208–215

Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD (1994) Functional recovery after fracture of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 76:751–758

Michel JP, Hoffmeyer P, Klopfenstein C et al (2000) Prognosis of functional recovery 1 year after hip fracture: typical patient profiles through cluster analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 55:M508–M515

Parker MJ, Gurusamy KS, Azegami S (2010) Arthroplasties (with and without bone cement) for proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:CD001706

Soderqvist A, Miedel R, Ponzer S et al (2006) The influence of cognitive function on outcome after a hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:2115–2123

Zakriya K, Sieber FE, Christmas C et al (2004) Brief postoperative delirium in hip fracture patients affects functional outcome at three months. Anesth Analg 98:1798–1802 (Table)

Di MM, Vallero F, Di MR et al (2003) Functional recovery and length of stay after hip fracture in patients with neurologic impairment. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 82:143–148

Hershkovitz A, Kalandariov Z, Hermush V et al (2007) Factors affecting short-term rehabilitation outcomes of disabled elderly patients with proximal hip fracture. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88:916–921

van Balen BR, Steyerberg EW, Polder JJ et al (2001) Hip fracture in elderly patients: outcomes for function, quality of life, and type of residence. Clin Orthop Relat Res 390:232–243

Zuckerman JD (1996) Hip fracture. N Engl J Med 334:1519–1525

Tinetti ME (2003) Clinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med 348:42–49

van den Bekerom MPJ, Hilverdink E, Sierevelt IN et al (2010) A randomized controlled multicenter trial comparing hemiarthroplasty with total hip arthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br 10:1422–1428

Khan SK (2009) Timing of surgery for hip fractures: a systematic review of 52 published studies involving 291, 413 patients. Injury 40:692–697

Association of Surgeons of the Netherlands (Nederlandse Vereniging Voor Heelkunde) (2006) Guideline; treatment of femoral neck fractures in elderly 1–47

Byrd JW, Jones KS (2000) Prospective analysis of hip arthroscopy with 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy 16:578–587

Potter BK, Freedman BA, Andersen RC et al (2005) Correlation of Short Form-36 and disability status with outcomes of arthroscopic acetabular labral debridement. Am J Sports Med 33:864–870

Harris WH (1969) Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 51:737–755

Bland JM, Altman DG (1997) Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 314:572

Cronbach LJ (1951) Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of test. Psychometrika 16:297–334

Streiner DL, Norman GR (2003) Selecting the Item In: Health measurement scales; a practical guide to their development and use. Oxford University Press, New York pp 72–73

Magaziner J, Simonsick EM, Kashner TM et al (1990) Predictors of functional recovery one year following hospital discharge for hip fracture: a prospective study. J Gerontol. 45:M101–M107

Nilsdotter AK, Lohmander LS (2002) Age and waiting time as predictors of outcome after total hip replacement for osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 41:1261–1267

Davis AM, Agnidis Z, Badley E et al (2006) Predictors of functional outcome two years following revision hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:685–691

de Groot IB, Reijman M, Terwee CB et al (2007) Validation of the Dutch version of the hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score. Osteoarthr Cartil 15:104–109

Lee YK, Chung CY, Koo KH et al (2011) Transcultural adaptation and testing of psychometric properties of the Korean version of the hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS). Osteoarthr Cartil 19:853–857

Nilsdotter AK, Lohmander LS, Klassbo M et al (2003) Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS)–validity and responsiveness in total hip replacement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 4:10

Ornetti P, Parratte S, Gossec L et al (2010) Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the French version of the Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) in hip osteoarthritis patients. Osteoarthr Cartil 18:522–529

Soderman P, Malchau H (2001) Is the Harris hip score system useful to study the outcome of total hip replacement? Clin Orthop Relat Res 384:189–197

Bryant MJ, Kernohan WG, Nixon JR et al (1993) A statistical analysis of hip scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br 75:705–709

Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware JE Jr (1995) The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey–I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Soc Sci Med 41:1349–1358

Siu AL, Penrod JD, Boockvar KS et al (2006) Early ambulation after hip fracture: effects on function and mortality. Arch Intern Med 166:766–771

Little JP (1995) Consistency of ASA grading. Anaesthesia 50:658–659

Haynes SR (1995) An assessment of the consistency of ASA physical status classification allocation. Anaesthesia 50:195–199

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the local Arthro trial researchers: Dik F. de Zwart, MD (St. Antonius Hospital, Sneek), Dick M. Werkman, MD (St. Deventer Hospitals), Paul Olsthoorn, MD (Slotervaart Hospital, Amsterdam), J. de Waal Malefijt, MD, PhD (St. Elisabeth Hospital, Tilburg), Jan. B. A. van Mourik, MD, PhD (Maxima Medical Center, Veldhoven), Cees F. van der Jagt, MD (Laurentius Hospital, Roermond). The authors are also grateful to Ibilola R. O. Odonde (University College London) for reading through the manuscript. Without the continuous support of the AO-Documentation Center in Davos, Switzerland, this study could not have been realized.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Reuling, E.M.B.P., Sierevelt, I.N., van den Bekerom, M.P.J. et al. Predictors of functional outcome following femoral neck fractures treated with an arthroplasty: limitations of the Harris hip score. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 132, 249–256 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-011-1424-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-011-1424-0